Abstract

With the United States Supreme Court’s Janus Decision, public-sector employees who were covered by a union contract but had not joined the union were free to choose whether to pay fair-share agency fees or not. Based on Brehm and Cohen’s (1962) postulate attached to cognitive dissonance theory—that dissonance arousal is contingent on free choice—we examined a downstream effect of the Decision on after Janus fee-paying employees, in which, ostensibly, fee-paying avoids dissonant cognitions between choosing not to pay and benefiting from collective bargaining. We predicted that these dissonant-avoidant employees—or, alternatively, these consonant-striving employees—would also strive to align cognitions when questioned about their stance on right-to-work laws and their willingness to act publicly in accordance with their stance. Using survey data from matched subsamples of no-choice paying employees before Janus and free-choice paying employees after Janus, we found that only after Janus employees showed consistency between their stance and their willingness to act publicly, a consistency that suggests a downstream effort to maintain consonance. In conjunction with the postulate and our results, we suggest that when free choice is present, dissonance avoidance not only predicts the nonobvious immediate effect of the Decision but also the downstream effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Consider a sample of 2018 headlines representative of those published in popular press periodicals (e.g., The New York Times, The Washington Post) on the day of the United States Supreme Court’s Janus Decision—a Decision that struck down a State law that required public-sector employees who were covered by a union contract but had not joined the union to pay fair-share agency fees for the cost of collective bargaining: “With Janus, the Court Deals Unions a Crushing Blow. Now What?”, “The Supreme Court May Have Just Killed Public Unions”, “With Janus, the Supreme Court Guts the Modern Labor Movement”, and “Preparing for the Worse: Unions Brace for Loss of Members and Fees in Wake of Supreme Court Ruling”. Consider also a sample of 2019 headlines representative of those published in the same periodicals six months to a year after the Decision: “Public-Sector Unions Stay Strong, 1 Year After Ruling in Illinois Case Banned Mandatory Fees”, “Workers Chose to Stick with Their Unions Despite Janus Ruling”, “Reports of the Labor Movement’s Death Greatly Exaggerated”, and “Janus Barely Dents Public-Sector Union Membership”.Footnote 1

Implied by these and other 2018 and 2019 headlines is a difference between the expected effect of the Janus Decision and the actual effect of the Decision. Expected by court observers was that public-sector dues-paying members and fee-paying employees would become nonpaying “free-riders”—employees who benefit from a union contract but bear no cost for collective bargaining—the result of which would diminish financial resources to maintain memberships and to conduct effective bargaining (Scheiber, 2018, “Supreme Court Defeat for Unions Upends a Liberal Money Base”).Footnote 2 As indicated, neither took place in the year after the Decision or the next, nor in subsequent years (DiSalvo, 2022, “By the numbers: Public Unions’ Money and Members Since Janus v. AFSCME”; Giles, 2019, “A Blow But Not Fatal: 9 months after Janus, AFSCME Reports 94% Retention”; Heflin, 2020, “Death Knell Decision by Supreme Court Has Yet to Kill Unions”).

Based on cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957; Festinger et al., 1956), which is often used to predict nonobvious attitudinal and behavioral outcomes, the actual effect of the Janus Decision was unsurprising. In fact, the effect (hereafter referred to as the immediate effect) is consistent with the theory. In this field study, concomitant with the immediate effect, we suggest a downstream effect. To show the downstream effect, we drew survey data from public-sector fee-paying employees before and after the Decision and examined their stance on right-to-work laws and their willingness to act publicly in accordance with their stance. Before reporting on our study’s methods and results, we provide background information to contextualize the Decision and to introduce embedded contextual terms to better understand the effect.

Background and terms

The Janus Decision (Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, 2018) is particularly noteworthy because it broke with decades of precedent. In 1977 the United States Supreme Court ruled in the Abood Decision (Abood Et Al. v. Detroit Board of Education Et Al., 1977) that unions could collect fair-share agency fees from public-sector employees who were covered by a union contract but had not joined the union. Based on the ruling, these agency fees could be used to pay for the cost of collective bargaining and associated activities (e.g., time spent on bargaining preparation), but could not be used for political activities (e.g., legislative pursuits). But, as argued on behalf of the appellant in the Janus Decision, agency fees violated a constitutional right—that when public-sector unions bargain over salaries and pensions, they are engaged in a form of political speech designed to influence government policy, and that by requiring employees to help pay for this form of speech, even when they agreed with a union’s stance, was a violation of their free speech (a First Amendment violation). Writing for the majority opinion, Justice Samuel Alito agreed and argued that union efforts to resist government budget cuts or to be involved in issues like merit pay for employees constituted examples of activities that were intrinsically political, adding that the Abood Decision was poorly conceived and inconsistent with the free speech amendment.Footnote 3

The significance of the Janus Decision is made vivid against a background of prior legislative decisions and court rulings, beginning with the signing of the sweeping 1935 National Labor Relations Act—known as the Wagner Act—guaranteeing employees the right to join a union (and to strike), in which unions could negotiate a closed shop security agreement with employers. Such an agreement—often referred to as a union contract—requires employees to join as paying members before employment (i.e., join as dues-paying members). The agreement gives unions an unrestricted right to represent all employees (through collective bargaining) and to require all employees to share equally in the cost of collective bargaining. A variant of the closed shop agreement is a union shop agreement—an agreement which requires employees to join as paying members after a probationary period of employment. This kind of agreement adds a restriction to the right of unions to collect dues. Although, by law, collective bargaining must apply to all (nonmanagerial) employees within a unit, probationary employees are exempt from paying dues.

Further restrictions on unions are seen in the 1947 Labor-Management Relations Act—known as the Taft-Hartley Act—a so-called right-to-work law that allows employees to opt out of paying dues, a law already on the books in 11 States either through legislative action or constitutional amendment. The Act empowered States to restrict security agreements to an agency shop, wherein employees before or after employment could forgo paying dues in favor of paying fair-share agency fees (i.e., become fee-paying employees). Emboldened by the Act, 17 States passed similar laws under the banner of a right-to-work State. Subsequent State constitutional amendments restricted unions further by outlawing the agency shop in favor of an open shop. Under this security agreement, collective bargaining is permitted, but employees before or after employment are not required to pay fair-share agency fees.

With the Janus Decision as the culminating restriction placed on public-sector unions—the “crushing blow” dealt to unions by the Decision—public-sector security agreements are presently right-to-work agreements. Left standing is the open shop. For public-sector unions, the exclusivity of an open shop is a game-changer. Consider an agency shop in any one of the 22 non-right-to-work States before and after the Decision. Before the Decision, unions could count on fair-share agency fees to help defray the cost of collective bargaining. After the Decision, they could not. Consider also the game-changing experience of fee-paying employees in any one of these States before and after the Decision—a change from paying a mandatory agency fee to a choice between paying or not paying a fee.

Theory and effects

According to cognitive dissonance theory, individuals strive to maintain consistency in their attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behaviors (i.e., to maintain a state of consonance) by avoiding dissonant cognitions and by aligning cognitions under conditions of dissonance arousal (for applied studies, see Brett et al., 1995; Doran et al., 1991; Mellor & Decker, 2020; Mills, 1958; Moore et al., 2014). As postulated by Brehm and Cohen (1962), implicit (and often overlooked) in dissonance predictions is the role of free choice in dissonance arousal (see Brehm, 1956 for the first empirical demonstration). Put simply, for dissonance arousal to be a source of motivation, free choice must be present. With free choice, individuals are expected to react to internal pressure to reduce dissonant cognitions and align cognitions to maintain a state of consonance. Without free choice, individuals are not expected to react to internal pressure to reduce dissonant cognitions; that is, internal pressure is offset by external no-choice demands.

How is the immediate effect of the Janus Decision consistent with cognitive dissonance theory? Assumed is that not paying a fair-share agency fee for collective bargaining and benefiting from collective bargaining represent dissonant cognitions. Whereas, paying fair-share agency fees in non-right-to-work States before the Decision is a fait accompli (choice is absent), paying agency fees after the Decision in these States is not (choice is present). As such, fee-paying after the Decision is a predictable outcome of dissonance avoidance. That is, under conditions of free choice and dissonance arousal, fee-paying represents dissonance avoidance—a striving for consonance.

Consistent with theory and shown in applied studies are downstream effects concomitant with avoidance of dissonant cognitions (for example studies, see Moore, 2008, 2014; Pozner et al., 2019; Wakeman et al., 2019). Put simply, to the extent that dissonance avoidance represents a striving for consonance, striving to maintain consonance follows. To show a downstream effect concomitant with the immediate effect of the Janus Decision, we asked fee-paying employees before and after the Decision about their stance on right-to-work laws and their willingness to act publicly in accordance with their stance. Faced with this question, fee-paying employees after the Decision should show consistency between their stance and their willingness to act publicly. However, the same cannot be said for fee-paying employees before the Decision. Given absent free choice, striving for consonance and maintaining consonance should also be absent.Footnote 4

Prediction model

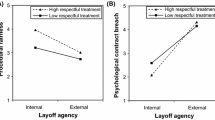

To test the downstream effect, we constructed a prediction model and drew survey data from public-sector fee-paying employees in non-right-to-work States before and after the Janus Decision. By positioning their stance on right-to-work laws as a predictor and their willingness to act publicly in accordance with their stance as an outcome, the effect is shown if the Decision moderates the predictor-outcome relationship, such that the relationship is shown by fee-paying employees after the Decision but not by fee-paying employees before the Decision (see Fig. 1).

Here is the prediction hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis: In reference to public-sector fee-paying employees in non-right-to-work States, the relationship between their stance on right-to-work laws and their willingness to act publicly in accordance with their stance is conditional on the Janus Decision, such that the relationship is shown by fee-paying employees after the Decision but not by fee-paying employees before the Decision.

Method

Survey procedure

Anonymous survey data were collected from American employees in two 3-month periods: 3 months before the Janus Decision (beginning in April 2018) and 3 months after the Decision (ending in September 2018).Footnote 5 Survey sites were community gatherings and public transportation areas (e.g., farmers’ markets, licensed bingo halls, tourist information centers, commuter train stations).

With permission obtained at each site, the researchers circulated flyers with the following information:

“Can you volunteer to take this survey? You can if you are employed in the U.S. and not a union member and not a full-time student. The survey is anonymous—no names. The survey takes about 10 minutes. The survey cannot be mailed. $5 is given for taking the survey. Please ask the researcher for a survey.”

Employees who responded to the flyer were given a no-name informed consent form, a survey, a pencil, and an unmarked envelope. The researchers collected sealed envelopes, paid participants, and conducted onsite debriefing.Footnote 6

Sampling

To ensure sample eligibility, the following items were embedded in the survey: “In which State are you currently employed?”, “Have you held a position with your current employer for 3 months or more?”, “Are you currently a union member?”, “Are you currently eligible to be a union member?”, “Are you currently covered by a union contract?”, and “Are you currently paying an agency fee to a union?”.

To discern public-sector employment, the following items were also embedded: “Are you currently employed by a Local Government (city, town, county, State)?” and “Are you currently employed by the Federal Government?” Also, to discern past union membership, the following item was embedded: “Have you ever been a union member?”.

Four-hundred and twenty-eight surveys were collected with no missing data. Of these, 328 were counted as eligible from the following non-right-to-work States: Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island as well as the District of Columbia.

Because the eligible surveys represented different employees in two 3-month periods, we used demographic items to create matched subsamples. The matching variables were gender (man [0] or woman [1]), ethnic group (European American [0] or African American, Arabian American, Asian American, Latinx American [1]), and employment status (part-time [0] or full-time [1]).

Matching resulted in subsamples comprised of 82 employees in each time period (total N = 164). The subsamples were labeled before Janus fee-paying employees and after Janus fee-paying employees.

Note that subsample labels refer to time periods in which employees were surveyed, in which data drawn from employees in a free-choice condition is exclusive to the after Janus fee-paying employees subsample.

Definition

Fee-paying employees were asked to “Consider the following definition:

A union security agreement—often referred to as the union contract—is a legal contract negotiated and signed by a union and an employer. The contract sets a period of time and indicates the terms and conditions of employment—for example, compensation, work rules, and procedures for settling disputes.”

Predictor measure

Stance on right-to-work laws

Fee-paying employees were asked to “think about union security agreements” and then asked to read the following:

“Here are four such agreements:

A union and an employer...

- 1

. . . have agreed that employees are required to join as members of the union before they are employed.

- 2

. . . have agreed that employees are required to join as members of the union after they are employed.

- 3

. . . have agreed that employees are not required to join as members of the union before or after they are employed, but employees are required to pay for the cost to be represented by the union.

- 4

. . . have agreed that employees are not required to join as members of the union before or after they are employed, and employees are not required to pay for the cost to be represented by the union.”

Fee-paying employees were asked to “check one blank” after the following stem: “I privately support Local, State, and Federal laws...” The response options were: “... that allow a union and an employer to agree to 1,... that allow a union and an employer to agree to 2 but not 1,... that allow a union and an employer to agree to 3 but not 4,... that allow a union and an employer to agree to 4.”

Note that the numbered 1 to 4 agreements correspond to a closed shop (1), a union shop (2), an agency shop (3), and an open shop (4), where 1 is a shop least restrictive to a union and 4 is a shop most restrictive to a union, and where 1 indicates a stance of less support for right-to-work laws and 4 indicates a stance of more support for right-to-work laws.

As such, response options were coded as marked on a continuum of less to more support for right-to-work laws.

The percentage of coded responses were as follows: 1 (8.5%), 2 (9.8%), 3 (17.1%), and 4 (64.6%).

Moderator measure

Janus Decision

The Janus Decision was coded as either before the Decision (0) or after the Decision (1).

Outcome measure

Willingness to act publicly in accordance with stance on right-to-work laws

Fee-paying employees were asked to think about “your willingness to act publicly in support of Local, State, and Federal legislative efforts to secure laws that you privately support.”

Items were listed and prefaced with the stem: “In support of legislative efforts, I am willing to...” The five items were: “... lend my name to a newspaper ad”, “... advocate support on my personal website—for example, Facebook”, “... post a sign on my property or in my rental space”, “... attend a public rally—march too”, and “... sign a petition directed at my Local, State, or Federal representative”.

Response options were either “yes” or “no” for each item and were coded as 1 or 0, where 1 indicates willingness to act publicly.

The percentage of coded yes responses were as follows: newspaper ad (29.3%), personal website (18.9%), post a sign (9.1%), public rally, march (31.1%), and sign a petition (65.9%).

To evaluate the construct validity of a unidimensional scale, a principal components analysis was performed on the items. The analysis produced one eigenvalue greater than 1.00, eigenvalue = 2.573, percent of variance explained = 51.461. Item loadings for the component ranged from 0.562 to 0.810.

To evaluate the internal consistency of item responses in reference to unidimensionality, a Cronbach’s alpha (α) was computed. The unstandardized α was 0.740; the standardized α was 0.757.

Based on these analyses, item responses were averaged, yielding continuous scale values from 0.00 (less) to 1.00 (more) willingness to act publicly.

Covariates

To better isolate the moderated relationship, the demographics (age, gender, ethnic group, employment status, past union membership) were positioned as control variables (covariates) in the regression analyses. Also, to reduce the possibility of collinearity between main effects and the interaction term containing the main effects, the predictor variable and the covariates were mean-centered in the analyses (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

Sample zero-order correlations (rs), means (Ms), and standard deviations (SDs) for study variables and selected subsample variables are presented in Table 1.

A note on statistical equivalence

In viewing the result of preliminary and model tests, note that consistency was equated with statistical covariation, in which embedded in the assumption of covariation is nonindependence. That is, given two elements, covariation indicates that the variation of element A is consistent with (corresponds to) the variation of element B such that AB variation can be suggested as nonindependent.

Preliminary tests

Relationships between model variables were examined for all sampled employees. The relationship between the predictor variable and the outcome variable was significantly different from zero, suggesting that stance on right-to-work laws was associated with willingness to act publicly, r = -0.532, p < 0.01. The relationship between the predictor variable and the moderator variable was significantly different from zero, suggesting that stance on right-to-work laws was nonindependent of the Janus Decision, r = -0.264, p < 0.01. Also, the relationship between the moderator variable and the outcome variable was not significantly different from zero, r = 0.145, p > 0.05.

The relationship between the predictor variable and the outcome variable was significantly different from zero for after Janus fee-paying employees but not for before Janus fee-paying employees, r = -0.698, p < 0.01; r = -0.093, p > 0.05, respectively. A test for independent subsample correlations following r to z transformations confirmed that the predictor-outcome relationship for before and after Janus fee-paying employees was significantly different from zero, suggesting that the relationship between stance on right-to-work laws and willingness to act publicly may be moderated in relation to the Janus Decision, z(164) = -4.84, p < 0.01.Footnote 7

Summary of preliminary tests

The results of the preliminary tests are consistent with the expected predictor-outcome relationship: The association between stance on right-to-work-laws and willingness to act publicly is shown by after Janus fee-paying employees but not by before Janus fee-paying employees.

Model tests

To test the hypothesized moderation depicted in Fig. 1, a step-wise hierarchical regression was performed, in which a significant interaction between the predictor variable and the moderator variable suggests that the relationship between the predictor variable and the outcome variable is conditional on values of the moderator variable.

With the demographics as covariates in the regression, 3 steps are required. At step 1, willingness to act publicly is regressed onto the covariates. Next, at step 2, willingness to act publicly is regressed onto stance on right-to-work laws and Janus Decision as main effects. At step 3, the final step, willingness to act publicly is regressed onto Stance On Right-To-Work-Laws X Janus Decision as a two-way interaction effect.

The results of the analysis are presented in Table 2. As shown at step 3, above and beyond gender as a covariate effect, unstandardized B = -0.129, standardized β = -0.220, p < 0.01, employment status as a covariate effect, B = -0.176, β = -0.243, p < 0.01, stance on right-to-work laws as a main effect, B = -0.130, β = -0.431, p < 0.01, Stance On Right-To-Work-Laws X Janus Decision as an interactive effect was significantly different from zero, B = -0.178, β = -0.283, p < 0.01.

The effect size associated with the two-way interaction is indicated by a change in the squared multiple correlation (∆R2) at the final step. At this step, the interaction explained 6% of the variance in willingness to act publicly above and beyond the covariate effects and the main effects, ∆R2 = 0.058; ∆F(1, 155) = 17.511, p < 0.01.

To estimate coefficients and effect sizes associated with subsample slopes, subgroup hierarchical regressions were performed, in which 2 steps are required. For each subsample, at step 1, willingness to act publicly is regressed onto the covariates. Next, at step 2, willingness to act publicly is regressed onto stance on right-to-work laws.

For after Janus fee-paying employees, the relationship between stance on right-to-work laws and willingness to act publicly was negative and significantly different from zero, in which the explained variance in willingness to act publicly was 49% above and beyond the covariates, B = -0.221, β = -0.738 p < 0.01; ∆R2 = 0.486; ∆F(1, 75) = 136.765, p < 0.01. In contrast, for before Janus fee-paying employees, the relationship between stance on right-to-work laws and willingness to act publicly was not significantly different from zero, in which the explained variance in willingness to act publicly was 0% above and beyond the covariates, B = -0.002, β = -0.004 p > 0.05; ∆R2 = 0.000; ∆F(1, 75) = 0.002, p > 0.05.Footnote 8

To illustrate the interaction, the subsample slopes from the subgroup regressions are shown in Fig. 2.

Summary of model tests

The results of the model tests are consistent with the hypothesized moderation. The predictor-outcome relationship is conditional on the Janus Decision: The relationship between stance on right-to-work-laws and willingness to act publicly is shown by after Janus fee-paying employees but not by before Janus fee-paying employees.

Discussion

In line with the Brehm-Cohen postulate (Brehm & Cohen, 1962)—that dissonance arousal as a source of motivation is contingent on free choice—survey data collected from public-sector fee-paying employees before and after the Janus Decision in non-right-to-work States confirmed a dissonance prediction. To wit, as a downstream effect of dissonance avoidance vis-à-vis paying fees for collective bargaining when they did not have to, after Janus employees showed consistency when asked about their stance on right-to-work laws and their willingness to act publicly in accordance with their stance, suggesting a striving to maintain consonance. If before Janus employees—employees who did have to pay fees—had shown the same consistency, free choice and dissonance avoidance as the suggested basis of maintaining consonance would be untenable.

As seen in the data, the free-choice relationship for after Janus employees is inverse—that more support for right-to-work laws is associated with less willingness to act publicly—or, stated differently, that less support for right-to-work laws is associated with more willingness to act publicly. Stated in the latter sense, implied is that less support for right-to-work laws is associated with more support for unions to collect mandatory fees. Because a positive relationship could also suggest a downstream effect, a legitimate question is why inverse? An answer consistent with cognitive dissonance theory is that the inverse relationship represents a return to absent dissonance arousal. With mandatory fees reinstated, free choice to pay or not to pay would be absent, as would be striving for consonance and downstream striving to maintain consonance.Footnote 9

Contribution and limitations

Our field study contributes to the slender body of dissonance predictions in applied settings. Despite the vast number of confirmed predictions with undergraduates as participants, surprisingly few predictions have been confirmed with employees as participants (for exceptions, see Brett et al., 1995; Mellor & Decker, 2020). But before our results can be included in the canon of dissonance predictions, inferential limitations associated with our cross-sectional matched-sample design should be noted and, whenever possible, addressed with complementary designs. For example, our design did not control for before and after Janus Decision time-effects on survey responses. Although before Janus employees paid no-choice fees, the actual length of time in which they paid fees was not recorded. Also, not recorded was whether after Janus employees paid no-choice fees before the Decision or not, and if they did, for what length of time. Nor did our design track within-person before and after Decision responses. Doing so could provide a plausible inference of a dissonance-induced change effect linked to paying no-choice and free-choice fees. If and when time-series data become available in reference to the Decision, we suggest a sequential design in which time-effects and change-effects can be disentangled.Footnote 10

How else might our results be interpreted in contradistinction to cognitive dissonance theory? Consider the view that free-choice paying employees are on average more prounion—that, as indicated in our data, that their stance of less support for right-to-work laws indicates more support for mandatory dues/fees. As attractive as this view might be, apart from random variation, our data do not support that these employees are on average more or less willing to act publicly in accordance with their stance (see Footnote 7). Consider also the view that free-choice paying employees tend to be self-integrative, not particularly prounion as much as dedicated to the idea of being true to themselves in both word and deed, and as such, apt to present themselves accordingly. However, this view begs the question: Why aren’t no-choice paying employees equally self-integrative? Other theory- and research-based alternatives to dissonance theory might emphasize individual differences regarding fairness sensitivity, distributive justice, felt-obligation, and citizenship behavior, as well as propensity to internalize economic exchange principles, but the singular question remains why would consistency be shown by free-choice paying employees and not by no-choice paying employees? Framed in this way, it is difficult to exclude an answer that omits dissonance avoidance rooted in free choice—that, under conditions of free choice, immediate and downstream avoidance can be expected.

Conclusion

On an implication note, our results linked to cognitive dissonance theory bode well for the survival of American public-sector union memberships. Counting on the appeal of economic self-interest, in which dues-paying members and fee-paying employees would opt to become free-riders—reaping the benefits of collective bargaining without paying for them—we doubt that petitioners of the Supreme Court in relation to the Janus Decision considered the predictable effect of free-choice dissonance arousal. To the extent that free-choice paying employees are motivated to avoid dissonance and maintain consonance, our results suggest that they may be expected to maintain consistency between their stance on right-to-work laws and their willingness to act publicly in accordance with their stance, a consistency not shown by no-choice paying employees.

Data availability

The data for the study are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ON86OR.

Notes

See the Reference section for headlined articles listed by author.

Although the Court had expressed misgivings about the Abood Decision in prior rulings (e.g., Minnesota State Board for Community Colleges v. Knight; 82–898, 1984; https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/465/271.html), it had not done so in a way that predicted a First Amendment ruling that struck down mandatory agency fees (see Kramer, 2019 for hindsight reactions to the Janus Decision).

A literature search for psychological studies that cited the Janus Decision uncovered one study. Based on a person-center analysis conducted before the Decision, McKay et al. (2020) provided evidence that type of “member participator” predicted “freerider intentions” (intent not to pay dues), with “participators in all forms of union activities” showing the least intent to free-ride.

The data for model variables in this study have not been included elsewhere.

By intent, the $5 participant fee was provided to offset asking participants for their time in exchange for nothing. Against the prospect that the fee may have violated their voluntary status (i.e., may have been viewed as coercive), true to the wording of the flyer, and underlined by informed consent statements, the fee was given for “taking” the survey rather than for “completing” the survey. Of note, many participants chose to forgo the fee.

To test for subsample mean differences in reference to the predictor variable and the outcome variable, analyses of variance were performed, with demographics as covariates. Although after Janus fee-paying employees (vs. before Janus fee-paying employees) on average indicated a stance of less support for right-to-work laws, F(6, 157) = 12.460, p < .01, they did not indicate on average more or less willingness to act publicly, F(6, 157) = 3.541, p > .05.

A table of subgroup regression results is available from the author.

For skeptics in reference to our results who might ask why fee-paying employees would show a stance of more or less support for right-to-work laws or more or less willingness to act publicly in accordance with their stance when the Janus Decision made right-to-work the law of the land, the answer lies with what every American employee knows. Inasmuch as State legislatures pass laws and courts uphold or strike down laws, legislatures can and do revise laws and courts can and do reinterpret the basis by which laws should or should not be upheld or struck down. That is, laws are mutable, underpinned by a changing majority of voters who determine not only legislative memberships but also indirectly court appointed justices.

Within State and within union factors also warrant attention, including perceptions of who controls the legislature, the possibility of legislative change, the legislative calendar, the strength of the union movement, and the extent to which union officials were caught off guard by the Court ruling or, in anticipation of the ruling, sought extra support from members and fee-paying employees.

References

Abood Et Al. v. Detroit Board of Education Et Al. (1977). https://tile.loc.gov/storageservices/service/ll/usrep/usrep431/usrep431209/usrep431209.pdf

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Balingit, M., & Douglas-Gabriel, D. (2018). Preparing for the worse: Unions brace for loss of members and fees in wake of Supreme Court ruling. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/education/wp/2018/06/27/preparing-for-the-worst-unions-brace-for-loss-of-members-and-fees-in-wake-of-supreme-court-ruling/

Brehm, J. W. (1956). Postdecision changes in the desirability of alternatives. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52, 384–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041006

Brehm, J. W., & Cohen, A. R. (1962). Explorations in cognitive dissonance. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1037/11622-000

Brett, J. F., Cron, W. L., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (1995). Economic dependency on work: A moderator of the relationship between organizational commitment and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 261–271. https://doi.org/10.5465/256735

Coombs, C. (2018). The Supreme Court may have just killed public unions. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/nekxbw/supreme-court-janus-v-afscme-decision-may-have-just-killed-unions

DiSalvo, D. (2019). Janus barely dents public-sector union membership. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/janus-barely-dents-public-sector-union-membership-11550100582

DiSalvo, D. (2022). By the numbers: Public unions’ money and members since Janus v. AFSCME. Manhattan Institute. https://www.manhattan-institute.org/disalvo-public-unions-money-members-since-janus-v-afscme

Doran, L. I., Stone, V. K., Brief, A. P., & George, J. M. (1991). Behavioral intentions as predictors of job attitudes: The role of economic choice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.1.40

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Row, Peterson.

Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails: A social and psychological study of a modern group that predicted the destruction of the world. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/10030-000

Giles, H. (2019). A blow but not fatal: 9 months after Janus, AFSCME reports 94% retention. Working In These Times. https://inthesetimes.com/article/janus-afscme-supreme-court-union-labor-agency-fees

Heflin, J. (2020). Death knell decision by Supreme Court has yet to kill unions, Washington Examiner. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/death-knell-decision-by-supreme-court-has-yet-to-kill-unions

Hower, J. (2018). With Janus, the Supreme Court guts the modern labor movement. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/made-by-history/wp/2018/06/27/with-janus-the-supreme-court-guts-the-modern-labor-movement/

Jaffe, S. (2018). With Janus, the Court deals unions a crushing blow. Now what. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/27/opinion/supreme-court-janus-unions.html

Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31, Et Al. (2018). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/17pdf/16-1466_2b3j.pdf

Kramer, R. J. (2019). Janus one year later: Litigation has come. American Bar Association. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/state_local_government/publications/state_local_law_news/2018-19/summer/janus-one-year-later-litigation-has-come/

Lieb, D. A. (2019). Public-sector unions stay strong, 1 year after ruling in Illinois case banned mandatory fees. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-biz-janus-public-union-membership-20190712-jyf6iw5tkraqpdfl5727t4s6yi-story.html

McKay, A. S., Grimaldi, E. M., Sayre, G. M., Hoffman, M. E., Reimer, R. D., & Mohammed, S. (2020). Types of union participation over time: Toward a person-centered and dynamic model of participation. Personnel Psychology, 73, 271–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12339

Mellor, S., & Decker, R. (2020). Multiple jobholders with families: A path from jobs held to psychological stress through work-family conflict and performance quality. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 32, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-020-09343-1

Mills, J. (1958). Changes in moral attitudes following temptation. Journal of Personality, 26, 517–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1958.tb02349.x

Moore, C. (2008). Moral disengagement in processes of organizational corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 80, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9447-8

Moore, C., Wakeman, S. W., & Gino, F. (2014). Dangerous expectations: Breaking rules to resolve cognitive dissonance. Harvard Business School NOM Unit Working Paper No. 15–012. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2486576

Pozner, J.-E., Mohliver, A., & Moore, C. (2019). Shine a light: How firm responses to announcing earnings restatements changed after Sarbanes Oxley. Journal of Business Ethics, 160, 427–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3950-y

Scheiber, N. (2018). Supreme Court defeat for unions upends a liberal money base. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/01/business/economy/unions-funding-political.html

Stites, J., & Tang, A. (2018). After Janus, how to tilt the balance of power back to workers. In These Times, 42, 1–10. https://inthesetimes.com/features/janus_rebuilding_labor_free-rider_fix_labor_unions.html

Tang, A. (2019). Life after Janus. Columbia Law Review, 119 (3), 677–762. https://columbialawreview.org/content/life-after-janus/

Tibbitts, E. (2019). Reports of the labor movement’s death greatly exaggerated. Quad-City Times. https://qctimes.com/opinion/columnists/reports-of-the-labor-movements-death-greatly-exaggerated/article_9ddc3828-cee1-57ba-ace5-44f20257f059.html

Wakeman, S. W., Moore, C., & Gino, F. (2019). A counterfeit competence: After threat, cheating boosts one’s self-image. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 82, 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.01.009

Workers chose to stick with their unions despite Janus ruling. (2019). St. Louis/Southern Illinois Labor Tribune. https://labortribune.com/workers-chose-to-stick-with-their-unions-despite-janus-ruling/

Funding

Funding for the study was provided by the author’s department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures used in the study involving participants are in accordance with the ethical standards of the author’s institution and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study in the form of a no-name information sheet.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

As a team project from beginning to end, the “we” indicated in the article reflects the shared insight and work of many students, most notably Nicolle Anderson, Hope Burnaman, Ragan Decker, Adela Fejzaj, Samantha Mayo, Charles Sauer, and Sarah Wolfram.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mellor, S. A cognitive dissonance field study of American public-sector fee-paying employees in relation to the Janus Decision. Curr Psychol 42, 24812–24821 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03595-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03595-w