Abstract

Some studies suggest that narcissism, either grandiose, vulnerable, or normal, is empirically associated with healthy or pathological concern towards others. These relationships remain poorly documented, and existing research only offers theoretical rationales as to the nature of the narcissism–concern association. The present study aims to assess the relationships between the various types of narcissism and concern while including the mediating role of explicit motives. French-speaking adults (n = 213) completed self-report questionnaires measuring these constructs. Results of mediation analyses suggest that specific motives mediate the positive associations observed between vulnerable or grandiose narcissism and pathological concern as well as the negative associations observed between grandiose or normal narcissism and healthy concern. Thus, it seems that pathological concern could be used as a maladaptive self-regulation mechanism by both forms of pathological narcissism. Fear motives mediate both relationships, suggesting avoidance as the main drive behind pathological concern in pathological narcissism. Also, the negative association between normal narcissism and healthy concern is coherent with the antagonistic interpersonal style of this form of narcissism. Results add to the practical knowledge of narcissism through a better understanding of the factors involved in self-regulation mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Narcissism is gaining interest (Miller et al., 2017) considering its probable increase among the general population. Twenge and collaborators (2008), for instance, observed a 30% increase in narcissism as measured by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; Raskin & Hall, 1981) among American college students between 1979 and 2006. Moreover, this disorder is generally perceived as difficult to treat even by experienced clinicians (Kernberg, 2007).

Narcissism

In social psychology and personality research, narcissism is often conceived as a trait existing on a continuum from absent to extreme, impairing an individual’s adjustment at high or pathological levels (Derry et al., 2019). The midpoint of the continuum is frequently referred to as normal narcissism (NN), indicating that, while reflecting recognizable behavioral and affective dispositions, it contributes to self-esteem and well-being by increasing one’s perceived power over the environment (Oldham & Morris, 1995). NN notably promotes assertiveness through interpersonal dominance (Brown & Zeigler-Hill, 2004) and fuels achievement through competitive endeavors and a strong work ethic (Pincus et al., 2009). NN is also associated with a tendency to adopt positive illusions about the self (Descôteaux & Laverdière, 2019) and to trivialize information inconsistent with a positive self-image (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001), predisposing individuals with NN to encounter relationship problems (Miller & Campbell, 2008).

In clinical psychology, narcissism is generally considered through a categorical perspective (Derry et al., 2019), although this standpoint is not shared by all theorists in the field. For instance, Pincus et al. (2009) support a dimensional view of narcissism in which it is defined as an individual’s ability to maintain a relatively positive self-esteem through various regulatory processes of the self, affect, and the environment. In pathological narcissism, maladaptive self-regulatory mechanisms tend to be activated when faced with disappointments or threats regarding self-image. These maladaptive processes exist in varying degrees across individuals (Descôteaux & Laverdière, 2019; Pincus et al., 2009).

Pathological narcissism can be conceptualized in terms of two key features: grandiosity and vulnerability. Each type is associated with specific intrapersonal, interpersonal, and self-esteem regulation processes (Besser & Priel, 2010). Grandiose narcissism (GN) is characterized by the repression of negative aspects of the self and the distortion of external information that is incongruent with the grandiose self, leading to attitudes of superiority, an overvalued self-image, and grandiose fantasies (Pincus et al., 2009). These maladaptive intrapsychic processes translate behaviorally into interpersonal exploitation, lack of empathy, intense envy of the other, aggression, and exhibitionism (Pincus et al., 2009). Vulnerable narcissism (VN) is characterized by a depreciated self-image, interpersonal hypersensitivity, social withdrawal, and affects of shame, anger, and depression (Pincus & Lukowitsky, 2010). The intrapsychic self-esteem regulation processes partially resemble those of the grandiose form, in a sense that individuals suffering from it also engage in grandiose fantasies, but contrary to GN, concomitantly feel shame toward their needs and ambitions. Although both forms present a strong degree of egocentrism (Miller et al., 2017), the dominant affect of VN is shame which leads to the avoidance of interpersonal relationships due to a hypersensitivity to rejection and criticism (Pincus & Lukowitsky, 2010).

Narcissism, particularly in its pathological forms, is associated with interpersonal difficulties (Pincus et al., 2009) which arise as a consequence of indifferent, contemptuous, and devaluative behaviors towards others (Descôteaux & Laverdière, 2019). To develop a more complete picture of narcissism on an interpersonal level, concern, a concept that recently aroused the interest of researchers, could prove useful (Shavit & Tolmacz, 2014).

Concerns

Shavit and Tolmacz (2014) define a sense of concern as a positive attitude toward the well-being of others expressed as sadness at their distress and joy at their success. The primary condition to the presence of concern is the consideration of the other as a subject (Shavit & Tolmacz, 2014). Depending on how the self is perceived, that is, as a subject or as an object, the resulting concern will be either pathological or healthy. In pathological concern, the self is indeed de-subjectivized while the other is considered as a subject (Gerber et al., 2015). Individuals who manifest this type of concern repress and refuse to acknowledge their needs and overinvest themselves in meeting the needs of others (Shavit & Tolmacz, 2014). They tend to present low self-esteem, emotional emptiness, and shame (Friedemann et al., 2016). Pathological concern is also positively related to egoistic motives to caregiving and negatively related to life satisfaction (Shavit & Tolmacz, 2014). Healthy concern emerges when both self and others are experienced as subjects (Tolmacz et al., 2019), allowing the expression of a caring attitude toward others without neglecting self-associated needs (Tolmacz, 2010). Individuals with high levels of healthy concern do not fear rejection, are not unduly sensitive to it, and tend to maintain good self-esteem and life satisfaction (Gerber et al., 2015; Helgeson, 1994).

Concern and Narcissism

The fact that pathological narcissism and concern admit different forms complicates their relationship considerably (Friedemann et al., 2016). To clarify the situation, Tolmacz et al. (2019) conducted two studies assessing the narcissism-concern relationships in which Israeli adults were surveyed by completing questionnaires measuring their different forms: VN, GN and pathological and healthy concerns. Consistent with theoretical predictions, VN was positively and moderately related to pathological concerns in both studies. Being related to a weakened self-image (Pincus & Lukowitsky, 2010) and a fear of rejection, VN would lead individuals to develop pathological concern as a means of defending the self (Gerber et al., 2015). It would thus alleviate the feeling of not being considered by others by gaining some form of recognition and admiration without the fear of being humiliated (Friedemann et al., 2016).

GN was weakly and negatively related to pathological concern in the second study, which also appears coherent with the theory. GN is characterized by the avoidance of intimate relationships and a proneness to engage in dominating behaviors toward others (Sturman, 2000). Furthermore, GN is usually depicted as caring about self-image exaggeratedly, while adopting a demanding, aggressive, and exploitative attitude toward others as well as a disregard for their subjective needs, which is antagonistic to the development of concern (Friedemann et al., 2016) that requires the granting of a subject status to others.

In both studies, healthy concern appeared unrelated to both forms of pathological narcissism (Tolmacz et al., 2019). Individuals presenting healthy concern are oriented toward others, have a high sense of competence, are not afraid of rejection, and seek communion (Gerber et al., 2015). Accordingly, negative relationships between healthy concern and both forms of pathological narcissism would have been expected. The lack of significant relationships remains unclear but could partially result from the instruments used to measure narcissism. For instance, Konrath et al., (2016) did observe a significant negative relationship between GN and healthy concern.

The studies measuring both narcissism and concern cited above (Konrath et al., 2016; Tolmacz et al., 2019) remain, to our knowledge, the only ones to do so. As such, their results need to be replicated. In addition, closely related findings suggest that other variables might be involved in the narcissism–concern association. For instance, Shavit & Tolmacz (2014) found that pathological concern is associated with egocentric motives in providing care which serve to gain a sense of control or rewards in the future. In this sense, self-sacrificing self-enhancement, a component of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory (PNI; Pincus et al., 2009) assigned to VN, corresponds to behaviors and attitudes that are seemingly altruistic but would be motivated by a need to nurture an overvalued self-presentation (Diguer et al., 2020). Furthermore, individuals with GN may offer instrumental and emotional support to others while feeling contempt for the person being helped as they see the situation as evidence of their superior abilities and goodness (Pincus et al., 2009). These examples illustrate the possible incongruence between overt behavior and the actual underlying need, justifying the relevance of paying attention to the latter. These needs can be conceived in terms of motives, including those of individuals with a certain degree of narcissism which could, to some extent, constitute the explanatory elements of the links between the types of narcissism and concern (mediation effect).

Motives

Motives correspond to recurrent needs that orient, stimulate, and energize an individual’s behavior towards a goal (McClelland, 1985). They can be divided into two categories, explicit and implicit motives. Implicit motives refer to affective preferences for certain types of motivations and operate unconsciously (Schönbrodt & Gersenber, 2012). Explicit motives, on the other hand, guide the deliberate aspects of behavior and correspond to individuals’ self-concepts (Hagemeyer et al., 2016). Since this study assesses the frequency of behaviors in a specific context using an inventory of self-reported traits, explicit motives appear more relevant. They are divided into two components, one approach oriented, which includes four motives, and the other avoidance oriented, which includes 5 motives (Schönbrodt & Gerseber, 2012). Achievement opposes fear of failure and is defined as a concern for achieving standards of excellence and a willingness to feel satisfaction when a difficult task is achieved. Power opposes fear of losing control and fear of losing prestige and refers to the desire to have an impact on others by influencing their emotions, attitudes, or behaviors, and to an appetite for prestige or high status. Affiliation opposes fear of rejection and is defined as the desire to establish and maintain warm and friendly relationships. Intimacy opposes fear of losing emotional contact with the other and is defined as the desire to be close to others, to have deep and positive interactions through mutual and warm exchanges where self-disclosure is practiced.

Motives and Narcissism

In past research, GN has been positively related to the achievement and power motives (Jauk & Kaufman, 2018; Sturman, 2000). Positive and negative relationships have been found with the affiliation motive (Jauk & Kaufman, 2018; Sturman, 2000). This may reflect the polarized view held by individuals with GN for whom the other is essential to reflect admiration back to them, but if the expected admiration is not received, the other is devalued and ignored (Descôteaux & Laverdière, 2019). For VN, negative relationships with power, affiliation, and achievement motives were found (Jauk & Kaufman, 2018; Sturman, 2000). Fear motives were in general more related to VN than to GN (Jauk & Kaufman, 2018). Finally, NN has been positively linked to the power motive (Sturman, 2000). The sum of these results is consistent with prior knowledge about narcissism. Indeed, GN is often described as co-occurring with a desire for power, success, and insatiable admiration (Pincus et al., 2009). The set of negative affects (e.g., shame and powerlessness) linked to VN may inhibit achievement, affiliation, and intimacy-seeking behaviors, encouraging social withdrawal behaviors (Besser & Priel, 2010), especially when admiration from the other is not certain or expected (Pincus et al., 2009), and NN has been positively related to interpersonal dominance assertion in past research (Brown & Zeigler-Hill, 2004).

The NPI has been used as a measure of GN in many studies (Tolmacz et al., 2019; Sturman, 2000). Many have questioned its potential to capture GN, as the NPI tends to correlate positively and negatively with adaptive and maladaptive characteristics respectively (Emmons, 1984). Based on these considerations, they conclude that the NPI measures NN (Emmons, 1984; Pincus & Lukowitsky, 2010). Accordingly, it seems relevant to verify the relationships between narcissism, concern, and motives using the PNI to assess GN and VN and the NPI to assess NN.

Objectives and Hypotheses

The main objective of this study is to investigate the relationships between forms of narcissism and concern. To get a better understanding of these relationships, the second objective is to test whether motives mediate them. The formulation of the 3 following hypotheses is based on prior empirical (Konrath et al., 2016; Tolmacz et al., 2019) and theoretical (Pincus & Lukowitsky, 2010; Tolmacz, 2010) knowledge concerning these variables. The first hypothesis predicts that GN will be negatively associated with pathological and healthy concern. The second hypothesis predicts that VN will be positively associated with pathological concern and negatively associated with healthy concern. The third hypothesis predicts that NN will be negatively associated with pathological concern and positively associated with healthy concern. To get a better view of these three hypotheses, see Table 1. For all relationships, it is further postulated that the effects will be mediated by motives. Since no study has investigated the relationships between these three sets of variables, the full set of motives is included to explore all the possible mediation effects.

Method

Participants and Procedure

A sample size of 150 is necessary to ensure a minimal statistical power of 80% according to the Monte Carlo power analysis for indirect effects, the method currently suggested to determine the sufficient sample size required in mediation analysis (Schoemann et al., 2017). This estimation was made with a confidence interval set at 95% and an α of 0.05 and supposed, based on past research (for example, Tolmacz et al., 2019; Sturman, 2000), small to moderate associations between the three sets of variables (narcissism, concern, and motive). The current sample consists of 213 French-speaking adults from the Canadian province of Quebec (47 males and 166 females) who completed all the questionnaires, while 48 participants did not complete the full set and thus could not be included. Non-binary individuals (n = 2) also had to be excluded because the effect of gender was controlled in the analyses. The mean age is 33.84 years (SD = 16.3). Most participants are white (96.30%), in a relationship (51.70%), students (51.17%), and report their highest level of education as university (63.8%). Table 2 presents their socio-demographic characteristics in more detail.

Following approbation from the institutional ethics board of the authors’ university, participants were invited via different electronic means (social networks and emails) to complete the study questionnaires hosted on the Lime Survey online platform between February 2nd and 16th 2021. The average completion time was 30 min. Participation was completely anonymous and did not involve monetary compensation. Inclusion criteria were being at least 18 years of age and residing in the province of Quebec.

Measures

Participants completed six questionnaires to assess sociodemographic characteristics, narcissism (GN, VN, and NN), concern (pathological and healthy), and motives (power, accomplishment, affiliation, intimacy, and aggregated fear motives). Measured sociodemographic characteristics were similar to those usually included in related studies (e.g., Jauk & Kaufman, 2018; Sturman, 2000; Tolmacz et al., 2019): gender, ethnicity, age, education, occupation, annual income, and marital status.

Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. GN and VN were assessed using a French adaptation (Diguer et al., 2020) of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory (PNI; Pincus et al., 2009). The 52 items scored on a 6-point scale (0 = not at all like me to 5 = very much like me) assess seven facets of pathological narcissism: exploitativeness, grandiose fantasy, entitlement rage, contingent self-esteem, hiding the self, devaluing, and self-sacrificial self-enhancement. Two practically equivalent second-order structures have been proposed. The original assigns exploitativeness, grandiose fantasy, and entitlement rage to the grandiose dimension and the other four facets to vulnerable narcissism, while the other exchanges entitlement rage for self-sacrificial self-enhancement in the grandiose dimension and vice-versa (Wright et al., 2010). Given its theoretical soundness, we retained the original second-order structure to compute GN and VN. Like the original version, the French adaptation shows good internal coherence (0.79 ≤ α ≤ 0.84) and temporal stability (0.78 ≤ r ≤ .86) at the facet level. In the present study, Cronbach’s alphas were 0.94 for the total scale, 0.87 and 0.93 for the grandiose and vulnerable dimensions respectively.

Normal narcissism. NN was assessed with a French adaptation (Brin, 2011) of Raskin and Hall’s (1981) Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI). Only the 40 narcissistic items were included and rated on a 7-point scale (1 = totally agree to 7 = totally disagree). As the original version (Raskin & Hall, 1981), the French adaptation shows excellent total score internal consistency (α = 0.91) and test-retest fidelity (α = 0.92; Brin, 2011). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91 for the 40 items.

Pathological concern. The Pathological Concern Questionnaire (Shavit & Tolmacz, 2014) includes 18 items rated on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all to 7 = very much) – a higher score reflects more pathological concern. It shows good reliability, including high internal consistency (α = 0.89; Shavit & Tolmacz, 2014). A French adaptation of this instrument was produced by the researchers using the back-translation method (Vallerand, 1989). Cronbach’s alpha of the French adaptation used in this study was 0.90.

The French-Interpersonal Reactivity Index (F-IRI; Gilet et al., 2012), based on Davis’ (1980) original English version, measures empathy according to four factors (fantasy, personal distress, perspective-taking, and empathic concern). Only the empathic concern factor was used for this research, as it measures healthy concern, that is, the degree to which the respondent feels compassion and concern for others (Tolmacz et al., 2019). This factor has seven items rated on a seven-point scale (1 = “does not describe me well” to 7 = “describes me very well”; Gilet et al., 2012), a higher score reflects more healthy concern. As the original version (Davis, 1980), this instrument shows acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.70) and good test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.77). Overall, the F-IRI shows good construct validity and good convergent validity (Gilet et al., 2012). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75 for the seven items.

The Unified Motive Scale (UMS-10; Schönbrodt & Gerstenberg, 2012) measures explicit motives. It includes 54 items divided into two scales; scale A contains 36 items rated on a six-point scale that assess degree of agreement with statements about the person’s motives (1 = Strongly Disagree to 6 = Strongly Agree); scale B contains 18 items rated on a six-point scale that measures the importance of personal goals (1 = not important to me to 6 = extremely important to me). The UMS-10 counts five dimensions: power, achievement, affiliation, intimacy, and fear - a high score indicates a motive with a high influence within the individual’s functioning. The fear dimension includes five subcomponents: fear of failure, fear of rejection, fear of losing control, fear of losing emotional contact, and fear of losing reputation. Cronbach’s alphas for all dimensions are higher or equal to 0.82. The UMS-10 shows excellent convergent and divergent validity as well as a good test-retest score with a one-week delay (thetas higher than or equal to 0.86). The instrument was adapted into French using the reverse translation method (Vallerand, 1989). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alphas for the power, achievement, affiliation, intimacy, and fear dimensions were respectively 0.87, 0.87, 0.89, 0.77, and 0.86.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analysis data showed that two variables did not meet the normal distribution requirements: healthy concern and intimacy motive. Healthy concern was transformed using the square root of the variable’s reflection and the sign of the transformed scale was then reversed to re-establish the meaning of the original scale. Since the negative skewness of the intimacy motive was not severe and was not reduced by any of the usual transformations, it was left as is.

Several variables differed significantly between men and women, namely NN, healthy concern, and the motives of power, intimacy, and fear (see Table 3). Accordingly, the effect of gender was controlled in all mediation analyses by including it as a covariable in the model.

Main Analyses

In line with the first objective, simple linear regressions were conducted to verify the presence of significant total effect between forms of narcissism (independent variable; IV) and forms of concern (dependent variable; DV), controlling for gender. This step is required to determine which relationship could go through the second step of mediation analyses. Results of Table 4 show that, contrarily to the first hypothesis, a positive association between GN and pathological concern was found, while in agreement with the hypothesis, a negative relationship was observed between GN and healthy concern. In agreement with the second hypothesis, VN was positively related to pathological but nonrelated to healthy concerns. Finally, in contradiction with the third hypothesis, NN was negatively related to healthy and unrelated to pathological concerns. Given the absence of relationships between VN and healthy concern and between NN and pathological concern, these relations were not included in the mediation analyses.

In line with the second objective, we tested whether motives mediate some of the four narcissism-concern relationships described above. The tested models specify form of narcissism as predictor, form of concern as outcome and motives as mediator variables, with gender as covariable. The Preacher and Hayes (2004) Process Macro for SPSS was used to compute direct (independent of motives) and indirect (mediated by motives) effects of form of narcissism on form of concern. This convenient method outputs regression coefficients, p values, and confidence intervals for all relationships involved in the model and circumvents limitations associated with traditional mediation analyses based on the Sobel test (1982; see Preacher & Hayes, 2004).

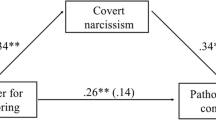

Figure 1 shows that only the fear motive positively mediated the positive relationship between GN and pathological concern, but that the fear motive fully mediated this relationship. Figure 2 shows that the fear motive also positively mediated the relationship between GN and healthy concern, bringing a positive contribution that only partially mediated their negative relationship. Figure 3 presents a somewhat more complex set of effects: the positive association between VN and pathological concern was partially mediated by the fear motive (positive effect) and by the power motive (negative effect). Lastly, Fig. 4 shows that the intimacy motive positively mediated the relationship between NN and healthy concern, its contribution only partially mediating their negative relationship.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationships between forms of narcissism and concern while assessing some possible mediating effects of motives. The following discussion is based on the structure of the hypotheses of the study.

First Hypothesis

Although the results showing a positive association between GN and pathological concern were not expected, they could nonetheless make sense on a theoretical level. Many have underlined GN as a defense against an inherent vulnerability (e.g., Kernberg, 1975; Kohut, 1977), which tends to be, according to Kohut (1977), “horizontally repressed”. At the heart of the definition of pathological concern also lies the concepts of repression and denial, which defend the individuals against their own needs (Gerber et al., 2015). Inasmuch as vulnerability is intimately associated with undesirable needs, both could be negated through defense mechanisms such as repression and, at least in part, be “replaced” by pathological concerns towards the needs of others. Furthermore, the fact that the positive GN–pathological concern association appears entirely mediated by the fear motive could reflect the long-recognized fear of dependency associated with GN (e.g., Kernberg, 1975), a state which would be more tolerable if attributed to the other through projection-related mechanisms.

The negative relationship between GN and healthy concern is consistent with the characteristics usually associated with GN (entitlement, superiority beliefs, exploitative behaviors, and devaluation of others; Pincus et al., 2009). Indeed, the other is perceived primarily as an object and used to satisfy a need to feel superior or to maintain an overvalued self-image. However, the observation that the fear motive tends to reduce the GN–healthy concern negative association could mean that the aforementioned projective-related defense mechanisms are not entirely effective, insofar as a certain need of others may be experienced. This would tend to confer to the other a partial status as a subject and thus generate conflict within a psyche that leans towards denying the other such a status.

The fact that GN appears positively associated with pathological concern and negatively with healthy concern tends to confirm that the investment in meeting the needs of others is not underpinned by a benevolent or empathic attitude towards them (e.g., Baskin-Sommers et al., 2014), but rather is utilitarian to the satisfaction of one’s self-centered needs.

Second Hypothesis

The strong positive association of VN with pathological concern replicates the results previously obtained by Tolmacz et al. (2019), who proposed that pathological concern develops in response to the feeling of not being seen by others. This type of concern thus serves as a strategy to gain recognition and admiration from others without the fear of being humiliated, belittled, or rejected (Tolmacz et al., 2019; Friedmann et al., 2016).

The fact that part of the VN–pathological concern association positively involves the fear motive gives further credit to Tolmacz et al.’s (2019) and Friedmann et al.’s (2016) conceptions of VN as a method of functioning rooted in the avoidance of aversive consequences through the enactment of pathological concern. However, the negative indirect effect of the power motive could mean that there is more to it, implying that the stronger the power motive association is with VN, the lesser it is with pathological concern. This could reflect a VN-related need to exert influence over the emotions, attitudes, and behaviors of others, i.e., to make the others conform to one’s needs or expectations, thereby reducing their status as subjects. Again, this could be indicative of some conflicting tendencies, but this time in the context of VN.

This idea of conflict could perhaps partly explain the absence of association between VN and healthy concern. By definition, VN would be negatively correlated with healthy concern as the self is considered as an object. Yet, given the positive correlations between VN and the fear motive and between the fear motive and healthy concern, a perception of self as a subject could co-exist with the perception of the self as an object, indicating a conflict in terms of self-representation. If this were the case, the indirect positive effect through the fear motive would oppose the direct negative effect of VN on healthy concern, creating a non-significant total effect. Of course, although it seems plausible given the present results, this possibility remains hypothetical and will require further testing.

Reflecting on GN and VN taken together, the fact that both forms were positively related to pathological concern may highlight the existence of egocentric motives in both of them. This appears compatible with the strong correlation usually observed between GN and VN (e.g., Wright et al., 2010), and with the often-observed alternation between grandiose and vulnerable phases in individuals with narcissistic pathology (Jauk & Kaufman, 2018; Pincus & Lukowitsky, 2010).

As a whole, the aforementioned findings suggest that the de-subjectification of the self to the benefit of the other implied in the concept of pathological concern may be more relative and complicated than theory suggests. The idea of conflict between opposing subjectification and de-subjectification tendencies appears plausible based on the results of the present study. Further investigations are clearly needed to give further support to this hypothesis.

Third Hypothesis

Contrary to expectations, NN was not related to pathological concern. NN, as measured by the NPI, has been shown to capture both healthy and pathological mechanisms (Ackerman et al., 2011). It may be that their effects tend to cancel each other out in global regression analyses. This possibility, like the one mentioned above to explain the absence of a relationship between VN and healthy concern, would certainly require further testing.

Regarding the negative association found between NN and healthy concern, similar results were obtained by Hepper et al. (2014). As previously mentioned, NN, while being mostly related to adaptive traits, is also associated with interpersonal dominance behaviors (Brown & Zeigler-Hill, 2004), exploitation of others (Emmons, 1984), relationship problems (Miller & Campbell, 2008), and an approach to others generally rooted in competitiveness and status-seeking (Bernard, 2014). These elements are antagonistic to the development of a caring attitude toward others which primarily characterizes healthy concern (Tolmacz, 2010). Through the egocentricity emanating from its characteristics, NN seems more compatible with a focus on the person’s own needs than on those of others. Healthy concern thus seems less compatible with the NN’s egocentric tendency. On the other hand, the intimacy motive, defined as a desire for warm and reciprocal exchanges, could partially counteract this egocentric tendency, thus reducing the overall negative effect of NN on healthy concern.

Strengths and Limitations

The exclusive use of self-reported questionnaires tends to generate methodological biases such as social desirability, positive illusory bias, as well as response biases induced by item order. In the present study, the order of the questionnaires was randomized to reduce potential sequencing effects. Furthermore, the sample, entirely composed of participants from a French speaking culture and in major part of women and individuals with a high level of education, limits generalization to different populations and cultures. The sample is also drawn from the normal population, thus restricting the range of scores obtained on pathological forms of narcissism and concern. The relationships between the variables might prove different if the sample also included a substantial number of people with pathological narcissism scores above the clinical thresholds. Replication of the results with different samples and populations is therefore necessary. Results pertaining to the intimacy motive are to be considered with caution as it did not meet the basic assumption of normality. Finally, the results are based on correlation-based analyses that do not meet the conditions for causality. In this sense, the possibility that other variables are responsible for the observed relationships cannot be ruled out.

This study has several implications. To our knowledge, this is the only one that assesses the mediation effect of explicit motives in the relationship between forms of narcissism and forms of concerns. It is also one of few studies to include three forms of narcissism (GN, VN, and NN) within the same study, using a substantial sample size. Furthermore, its findings suggest that the de-subjectification of self and others in both forms of pathological narcissism may prove more nuanced than expected and rooted in inner conflicts. They also incite to relativize the adaptive aspect of NN given its negative relationship with healthy concern. Overall, the results show the importance of considering the multiple facets of individuals’ dispositions and motivations to reveal the complexity of the mechanisms involved.

Future Studies

In conclusion, future studies should attempt to replicate the present results considering the limitations raised. It would also be relevant to replicate this study within a clinical sample to determine the best approach toward narcissism in a therapeutic setting. In addition, since the concepts of concern and empathy are related, it would seem relevant to compare their relationships to the types of narcissism in future studies. Finally, it may be of interest to replicate this study with the inclusion of implicit motives, less accessible to consciousness.

References

Ackerman, R. A., Witt, E. A., Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., & Kashy, D. A. (2011). What does the narcissistic personality inventory really measure? Assessment Journal, 18(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191110382845

Baskin-Sommers, A., Krusemark, E., & Ronningstam, E. (2014). Empathy in narcissistic personality disorder: From clinical and empirical perspectives. Personality Disorders: Theory Research and Treatment, 5(3), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000061

Bernard, L. (2014). Motivation and borderline personality, psychopathy, and narcissism. Individual Differences Research, 12(1), 12–30

Besser, A., & Priel, B. (2010). Grandiose narcissism versus vulnerable narcissism in threatening situations: Emotional reactions to achievement failure and interpersonal rejection. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(8), 874–902. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2010.29.8.874

Brin, J. (2011). Adaptation et validation française du Narcissistic Personality Inventory [Doctoral dissertation, Université Laval]. Université Laval digital archive. https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/bitstream/20.500.11794/22777/1/28305.pdf

Brown, R. P., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2004). Narcissism and the non-equivalence of self-esteem measures: A matter of dominance? Journal of Research in Personality, 38(6), 585–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2003.11.002

Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85

Derry, K. L., Ohan, J. L., & Bayliss, D. M. (2019). Toward understanding and measuring grandiose and vulnerable narcissism within trait personality models. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(4), 498–511. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000432

Descôteaux, J., & Laverdière, O. (2019). Normal and pathological narcissism: An integrative overview of the main North American psychoanalytic conceptualizations. Psychothérapies, 39(2), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.3917/psys.192.0055

Diguer, L., Turmel, V., Brin, J., Lapointe, T., Chrétien, S., Marcoux, L. A., & Luis, D. S. (2020). Translation and validation in French of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 52(2), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000140

Emmons, R. A. (1984). Factor analysis and construct validity of the narcissistic personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48(3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_11

Friedemann, Y., Tolmacz, R., & Doron, Y. (2016). Narcissism and concern: The relationship of self-object needs and narcissistic symptoms with healthy and pathological concern. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 76, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1057/ajp.2015.60

Gerber, Z., Tolmacz, R., & Doron, Y. (2015). Self-compassion and forms of concerns for others. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.052

Gilet, A. L., Mella, N., Studer, J., Grühn, D., & Labouvie-Vief, G. (2012). Assessing dispositional empathy in adults: A french validation of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 45(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030425

Hagemeyer, B., Dufner, M., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2016). Double dissociation between implicit and explicit affiliative motives: A closer look at socializing behavior in dyadic interactions. Journal of Research in Personality, 65, 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.08.003

Helgeson, V. S. (1994). Relation of agency and communion to well-being: evidence and potential explanations. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 412–418. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.412.

Hepper, E. G., Hart, C. M., & Sedikides, C. (2014). Moving narcissus: Can narcissists be empathic? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(9), 1079–1091. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214535812

Jauk, E., & Kaufman, S. B. (2018). The higher the score, the darker the core: The nonlinear association between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01305

Kernberg, O. F. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. Northvale, NJ, Jason Aronson. https://doi.org/10.1192/S0007125000016214

Kernberg, O. F. (2007). The almost untreatable narcissistic patient. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 55(2), 503–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/00030651070550020701

Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of the self. International Universities Press

Konrath, S., Ho, M. H., & Zarins, S. (2016). The strategic helper: Narcissism and prosocial motives and behaviors. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 35, 182–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9417-3

McClelland, D. C. (1985). How motives, skills, and values determine what people do. American Psychologist, 40(7), 812–825. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.40.7.812

Miller, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2008). Comparing clinical and social-personality conceptualizations of narcissism. Journal of Personality, 76(3), 449–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00492.x

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Hyatt, C. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2017). Controversies in narcissism. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13(1), 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045244

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12(4), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1204_1

Oldham, J. M., & Morris, L. B. (1995). The new personality self-portrait: Why you think, work, love, and act the way you do. Bantam Books

Pincus, A. L., Ansell, E. B., Pimentel, C. A., Cain, N. M., Wright, A. G. C., & Levy, K. N. (2009). Initial construction and validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016530

Pincus, A. L., & Lukowitsky, M. R. (2010). Pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 421–446. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131215

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods Instruments & Computers, 36, 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553

Raskin, R., & Hall, C. S. (1981). The narcissistic personality inventory: Alternate form reliability and further evidence of construct validity. Journal of Personality Assessment, 45(2), 159–162. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4502_10

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617715068

Schönbrodt, F. D., & Gerstenberg, F. X. R. (2012). An IRT analysis of motive questionnaires: The unified motive scales. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(6), 725–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.08.010

Shavit, Y., & Tolmacz, R. (2014). Pathological concern: Scale construction, construct validity, and associations with attachment, self-cohesion, and relational entitlement. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 31(3), 343–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036560

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290–312)

Sturman, T. S. (2000). The motivational foundations and behavioral expressions of three narcissistic styles. Social Behavior and Personnality, 28(4), 393–408

Tolmacz, R. (2010). Forms of concern: A psychoanalytic perspective. Prosocial Motives, Emotions, and Behavior: The Better Angels of Our Nature, 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/12061-005

Tolmacz, R., Friedemann, Y., Doron, Y., & Gerber, Z. (2019). Narcissism and concern for others: A contradiction in terms? Current Psychology, 40, 1814–1823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0113-3

Twenge, J. M., Foster, J. D., Konrath, S., Foster, J. D., Campbell, W. K., & Bushman, B. J. (2008). Egos inflating over time: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of Personnality, 76(4), 875–902. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00507.x

Vallerand, R. J. (1989). Vers une méthodologie de validation trans-culturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: Implications pour la recherche en langue française. Canadian Psychology, 30(4), 662–680. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079856

Wright, A. G. C., Lukowitsky, M. R., Pincus, A. L., & Conroy, D. E. (2010). The higher order factor structure and gender invariance of the pathological narcissism inventory. Assessment -Odessa Then Thousand Oaks Ca-, 17(4), 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191110373227

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author’s Notes

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to a confidentiality clause in the consent form but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest and that no funding was received for conducting this study. Also, the questionnaires and methodology for this study were approved by the Human Research Ethics committee of the authors’ affiliated institution. Finally, informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lapierre-Bédard, A., Rancourt-Tremblay, Z., Marineau Painchaud, JA. et al. Narcissism and concern: The mediating role of explicit motives. Curr Psychol 42, 21693–21703 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03261-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03261-1