Abstract

This study compared the direct relationships of transformational, ethical, empowering, and servant leadership with a multidimensional construct of employee well-being. Employee well-being is conceptualized as a higher-order construct composed of four lower-order constructs of job satisfaction (hedonic), job engagement (eudaimonic), job stress (negative), and sleep quality (physical). This study also examined the mediating role of leader-member exchange (LMX). Data was collected in a two-wave online survey from 560 middle-level managers working in private banking and insurance sector organizations. Structural equation modeling technique was employed to find out the direct and indirect association of leadership styles with employee well-being. Results validated the hierarchical structure of employee well-being and revealed that transformational, empowering, and servant leadership promotes employee well-being directly. Except for servant leadership, all other leadership styles were indirectly associated with employee well-being through LMX. Servant leadership only affected employee well-being directly. Findings highlight the theoretical and practical significance of leadership styles and LMX for employee well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

United Nations (2015) ranked Good health and well-being as the third goal of the 17 sustainable development goals. A Scopus search with the keyword “employee well-being” reveals an exponential growth in the number of research articles and practitioner papers on the subject since 2015. For most individuals, their workplace is a significant life domain (Russell, 2008) because of the importance of work in their lives and the amount of time and effort they devote to it (Dagar & Pandey, 2021). As a result, organizational psychologists’ interest in understanding the well-being of people in their workplace is growing (Diener et al., 2017). Employee well-being is associated with positive outcomes at work (Di Fabio, 2017), such as enhanced employee creativity, problem-solving skills, pro-social behavior, and productivity (Bryson et al., 2017) and improved physical health (Diener & Chan, 2011). Leadership is one of the essential factors fostering employee well-being (Kuoppala et al., 2008). Different leader behaviors are associated with various indicators of employee well-being such as job satisfaction, job engagement, job stress, burnout, etc. (Inceoglu et al., 2018).

There are, however, two issues with the extant literature. First, there is no consensus on the most potent leadership behavior fostering employee well-being. Second, employee well-being has never been viewed as a multidimensional construct. The variables frequently used to understand employees’ overall well-being, such as psychological well-being, or subjective well-being, or job satisfaction, do not accurately reflect workplace well-being (Inceoglu et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2015) as none of those does provide insight into people’s experience and functioning in their work lives. Leadership literature has primarily focused on the hedonic form of well-being (e.g., job satisfaction) and has paid relatively less attention to the eudaimonic (Bartels et al., 2019), physical, and negative (Inceoglu et al., 2018) forms of well-being. Hence, employee well-being must include all the primary components of well-being (Keeman et al., 2017). In addition to providing a more accurate interpretation of well-being in the workplace, a multidimensional construct may be used to create interventions to improve employee well-being (Kun & Gadanecz, 2019). The objective of this study is threefold. First, to establish the validity of a multidimensional construct of employee well-being composed of hedonic, eudaimonic, negative, and physical dimensions. Second, to investigate the potent leadership behavior by comparing four dominant leadership (transformational, ethical, empowering, and servant) behaviors fostering employee well-being. And finally, to understand the mechanism linking leadership behaviors and employee well-being.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Multidimensional Nature of Employee Well-Being

Subjective well-being refers to people’s cognitive and affective evaluations of their life in different life domains (Bakker & Oerlemans, 2011; Diener et al., 2017). Subjective well-being is a multidimensional and multifactorial construct composed of life satisfaction, positive affect, negative affect (Diener et al., 1998), and flourishing (Diener et al., 2010). Employee well-being refers to the overall quality of the employees’ experience and functioning at work (Grant et al., 2007). Unlike subjective well-being, employee well-being has been overused as a unidimensional construct (Inceoglu et al., 2018). Based on Diener et al.’s (1991) definition of subjective well-being, employee well-being can include job satisfaction (as a cognitive evaluation of one’s job) and job engagement (affective experience of positive emotions at work), and job stress (affective experience of negative emotions at work).

Employee well-being includes psychological and physical well-being at work (Inceoglu et al., 2018; Sivanathan et al., 2012). Psychological well-being can be operationalized as affective and cognitive processes (Warr, 2013). Job satisfaction, job engagement, and burnout are examples of psychological well-being. Psychological well-being can have positive (i.e., job satisfaction, job engagement) and negative (i.e., job stress) forms (Inceoglu et al., 2018). Positive well-being is further divided into hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being. Hedonic well-being is the subjective experience of pleasure or cognitive and affective evaluation of work-life (e.g., contentment, comfort, and satisfaction; Guest 2017; Warr, 2013). On the other hand, eudaimonic well-being is the subjective vitality or the positive feeling of aliveness and energy (e.g., personal growth, vitality, engagement; Bartels et al., 2019; Warr, 2013). Physical well-being refers to bodily health and functioning (e.g., sleep quality, stress symptoms; Grant et al., 2007; Guest, 2017). Therefore, well-being needs to be understood as a multidimensional construct covering a range of indicators, at least one from the hedonic, eudaimonic, negative, and physical dimensions. Furthermore, a multidimensional approach to gauging employee well-being may yield more precise assessments (van Horn et al., 2004).

Given the pervasive influence of work on one’s life, all aspects of well-being get affected. Hence, employee well-being must not be just satisfaction from the job, the absence of mental or physical illness, or feelings of growth and vitality in the job. Employee well-being must include employee safety, health, satisfaction, and engagement at work (International Labour Organization, 2022). Employee well-being can be a multidimensional construct (Danna & Griffin, 1999; Inceoglu et al., 2018; Grant et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2015) because a common underlying construct seems to account for the relationships among more specific dimensions of employee well-being (van Horn et al., 2004). Researchers have conceptualized employee well-being as job satisfaction, tension, depression, burnout, and morale (Warr, 1987), as psychological and physiological well-being (Danna & Griffin, 1999; Liu et al., 2010), as job satisfaction, stress, burnout, and engagement (Rothmann, 2008), and as affective, professional, social, cognitive, and psychosomatic (van Horn et al., 2004). Though researchers offered different conceptualizations of employee well-being, none of the earlier conceptualizations cover all key forms (hedonic, eudaimonic, physical, and negative) of employee well-being (Danna & Griffin, 1999; Grant et al., 2007; Inceoglu et al., 2018).

For this study, employee well-being has been conceptualized as the combination of job satisfaction (hedonic), job engagement (eudaimonic), job stress (negative), and sleep quality (physical). This combination of employee well-being indicators also justifies Danna and Griffin’s (1999) call to include aspects of work and non-work domains. Job satisfaction, job engagement, and job stress are the experiences at work, whereas sleep quality reflects the spillover of the experiences at work domains into non-work domains. Furthermore, sleep is critical to employee health and well-being (Sianoja et al., 2020), and leaders are important factors influencing employees’ sleep (Barnes et al., 2020). Hence, the inclusion of sleep quality as a physical health dimension of employee well-being is justified.

Hierarchical Structure of Employee Well-Being

Research on the structure of employee well-being is still in its nascent stage (Zheng et al., 2015). In subjective well-being literature, four structures of well-being are found to be widely tested—separate components, hierarchical, causal, and composite—based on independence or relatedness of the components such as life satisfaction, flourishing, positive affect, and negative affect (Busseri, 2015; Suar et al., 2019). Out of those four structures, the hierarchical structural conceptualization of subjective well-being has been proven more robust (Busseri, 2018). Though Rothmann (2008) conceptualized employee well-being as a higher-order construct, it included only psychological dimensions of well-being. Hence, in line with the subjective well-being literature, employee well-being can be conceptualized as a hierarchical higher-order latent construct having four lower-order constructs (job satisfaction, job engagement, job stress, and sleep quality).

Leadership and Employee Well-Being

Many leadership behaviors (transformational, charismatic, transactional, authentic, ethical, empowering, servant, and laissez-faire) are associated with employee well-being (Inceoglu et al., 2018). However, there is an ongoing debate on the most effective leadership behavior for fostering employee well-being. Transformational leadership is the most dominant leadership behavior promoting employee well-being (Arnold, 2017; Inceoglu et al., 2018; Skakon et al., 2010; Zwingmann et al., 2014). However, there is a notable influence of charismatic (Cicero & Pierro, 2007), ethical (Chughtai et al., 2015; Yang, 2014), authentic (Rahimnia & Sharifirad, 2014), empowering (Gyu Park et al., 2017; Kim & Beehr, 2018a, b), and servant leadership behaviors (Chen et al., 2013; Coetzer et al., 2017) with various indicators of employee well-being such as job satisfaction, job engagement, burnout, job tension, stress symptoms, sleep quality. Following the call of Inceoglu et al., (2018) to find the relative importance of different leadership behaviors in predicting a multidimensional construct of well-being, this study compares the relationships of four leadership behaviors (transformational, ethical, empowering, and servant leadership) with employee well-being. Transactional, authoritarian, and passive-avoidant leadership are not included because of their negative association with employee well-being (Berger et al., 2019). There is a conceptual overlap between transformational and charismatic leadership (Yukl, 1999) and authentic and ethical leadership (Luthans & Avolio, 2003). Hence, transformational and ethical leadership and empowering and servant leadership were used to avoid redundancy.

Transformational Leadership and Employee Well-Being

Transformational leaders stimulate employees to be creative, achieve higher-order goals beyond self-interest (Bass & Avolio, 1994), and help meet employees’ psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competency (Gilbert & Kelloway, 2014). Transformational leaders foster autonomy through intellectually stimulating employees to devise their approaches to their work (Barling et al., 2010). Transformational leaders being individually considerate, meet their employees’ relatedness needs, where leaders develop strong relationships with employees built upon respect, support, and compassion. Transformational leaders also promote relatedness, ideologically influencing employees through a shared vision and fostering a sense of belonging. Finally, to help satisfy employees’ need for competence, transformational leaders, through inspirational motivation, encourage them to achieve higher goals and overcome obstacles to high performance. Hence, based on the self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2012), it can be argued that transformational leaders enhance employees’ psychological and physical well-being (Arnold et al., 2015) by meeting their basic psychological needs. Though linked to various dimensions of employee well-being (Arnold et al., 2007; Arnold, 2017; Berger et al., 2019; Walsh & Arnold, 2020) individually, transformational leadership has never been associated with multidimensional employee well-being. Hence, we propose that:

-

H1a: Transformational leadership will be positively associated with the multidimensional construct of employee well-being.

Ethical Leadership and Employee Well-Being

Ethical leaders treat subordinates with respect, abide by promises, allow subordinates to participate in decision-making, and clearly define expectations and responsibilities (Kalshoven et al., 2011). Demonstrating normatively appropriate conduct like trustworthiness, honesty, fairness, and care through personal behavior and interpersonal relationships, ethical leaders (Brown & Treviño, 2006) protect subordinates from unfair treatment (Kalshoven & Boon, 2012) and meet their relatedness needs. Ethical leaders allow followers to have a voice and give them a lot of control over their decisions (Brown et al., 2005), and meet the autonomy need of the employees (De Hoogh & Den Hartog, 2008). Ethical leaders’ power-sharing and role clarification allow subordinates to improve their skills, enhance their efficacy (Resick et al., 2006; Yukl, 2010), and meet their competence needs. They exhibit active responsiveness (Goldman & Tabak, 2010) and provide feedback and recognition (van Dierendonck et al., 2004), enabling an enriched work atmosphere. Drawing from the self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2012), it can be argued that ethical leaders would enhance employee well-being by mobilizing job resources and defending and protecting subordinates from unfairness. Leaders’ support for ethical behavior can boost job satisfaction (Koh & Boo, 2004) and reciprocal job dedication or job engagement (Brown et al., 2005) of the subordinates. Procedural and interpersonal justice are also negatively associated with job stress (Judge & Colquitt, 2004). Employees are expected to experience less stress in the just environment created by ethical leaders where everyone behaves ethically. Hence, we hypothesized that:

-

H1b: Ethical leadership will be positively associated with the multidimensional construct of employee well-being.

Empowering Leadership and Employee Well-Being

Leading by example, participative decision-making, coaching, informing, and showing concern for subordinates are the five important empowering leadership behaviors (Arnold et al., 2000). These five factors are related to the basic needs as per the self-determination theory (O’Donoghue & van der Werff, 2021). Coaching employees, for example, promotes competence, whereas showing concern for and interacting with them promotes relatedness. Participatory decision-making enables choice, and supplying vital information empowers employees to make autonomous decisions (Srivastava et al., 2006). As a result, empowering leaders helps satisfy subordinates’ basic psychological needs, resulting in employee well-being (O’Donoghue & van der Werff, 2021). Empowerment is a positive state of mind that improves employees’ psychological well-being, job engagement (Gyu Park et al., 2017), and job satisfaction (Vecchio et al., 2010). In addition, it reduces burnout (Andrews & Kacmar, 2014) and psychological distress (Fitzsimons & Fuller, 2002). Based on the self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2012), it can be argued that empowering leaders would enhance employee well-being by helping subordinates appreciate the significance of work, engaging them in decision-making, trusting their abilities to succeed, and reducing bureaucratic hurdles (Ahearne et al., 2005). Hence, we hypothesize that:

-

H1c: Empowering leadership will be positively associated with the multidimensional construct of employee well-being.

Servant Leadership and Employee Well-Being

Servant leaders prioritize serving their subordinates (Greenleaf, 1977). Servant leaders assist followers in achieving autonomy by empowering them to take the initiative, be creative, learn from mistakes, take responsibility, and handle challenging situations (Liden et al., 2008). Servant leaders devote a significant amount of time and effort knowing their followers’ interests, competencies, and career aspirations because they are genuinely concerned about and prioritize the development of their subordinates (Greenleaf, 1998). Servant leaders strive to understand their followers’ career goals in detail, create opportunities to improve or develop new abilities and aid them in accomplishing their objectives (Liden et al., 2008). Furthermore, servant leaders exhibit altruistic sensitivity to their followers’ well-being, resulting in meaningful trustworthy dyadic connections and the cultivation of a psychologically secure and fair climate (Schaubroeck et al., 2011). As servant leaders meet all the basic psychological needs of the subordinates, based on the self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2012), it can be argued that servant leaders would enhance the well-being of the subordinates. Empirical evidence also suggests that servant leadership is positively associated with subordinates’ job satisfaction (Mayer et al., 2008), job engagement (Carter & Baghurst, 2014), and negatively associated with job stress (Jaramillo et al., 2009). Therefore, it can be hypothesized that:

-

H1d: Servant leadership will be positively associated with employee well-being.

LMX as a Mediator Between Leadership Styles and Employee Well-Being

LMX explains leaders’ high-quality and low-quality relationships with each subordinate (Sparrowe & Liden, 1997). According to the conservation of resources (COR) theory, people are motivated to acquire, retain, and protect resources (Hobfoll, 1989, 2002). Drawing from the COR theory (Hobfoll, 2002), LMX can be considered as a contextual resource that enhances employee well-being. Employees need job resources to deal with job demands and unfavorable work conditions (Arnold et al., 2000). Leaders provide job resources (e.g., support, autonomy, feedback, information) to the employees, which reduce job demands and the associated adverse physical or psychological consequences (Vincent-Höper & Stein, 2019). Based on the gain spiral corollary of the COR theory (Hobfoll, 2011), high-quality LMX can be considered as the initial resource gain, which begets further gains in terms of support, respect, trust, etc., from the leader. The quality of LMX largely depends on the leadership style (Walumbwa et al., 2011). Hence it is imperative to understand how different leadership styles foster employee well-being through LMX.

This study proposes LMX as a mediator between leadership styles and employee well-being for three reasons. First, there is ample evidence that different leadership styles promote high-quality LMX (Inceoglu et al., 2018) and high-quality LMX enhances employee well-being (Huell et al., 2016). Second, a non-linear or curvilinear relationship exists between LMX and well-being (Harris & Kacmar, 2006; Hochwarter, 2005). Too strong high-quality LMX might adversely influence employee well-being. Because as LMX relationship quality improves, subordinates may have more expectations (Blau, 1964), obligations (Gouldner, 1960), and roles to fulfill (Liden & Graen, 1980). Finally, according to the LMX differentiation theory (Henderson et al., 2009), it is expected that different leadership behaviors will have different levels of exchange relationships with subordinates, resulting in different consequences. Hence, it might be interesting to understand the indirect relations of transformational, ethical, empowering, and servant leadership with employee well-being through LMX to understand the causal mechanisms through which these leadership styles are associated with employee well-being.

LMX as a Mediator Between Transformational Leadership and Employee Well-Being

The positive association between transformational leadership and LMX is well established (Ng, 2017; O’Donnell et al., 2012; Rockstuhl et al., 2012; Yukl et al., 2009) and can be attributed to the conceptual overlap between the two concepts (Wang et al., 2005) contributing to the similar employee and organizational outcomes (Boer et al., 2016). By providing personal care to subordinates, transformational leaders play a key role in cultivating a close bond with the subordinates (Ng, 2017; Rockstuhl et al., 2012). Leader-subordinate bonding strengthens trust among the subordinates, leading to more satisfaction and less stress (Ng, 2017; Rockstuhl et al., 2012). Thus, LMX is more proximal to subordinates’ work attitudes (Boer et al., 2016) and well-being (Epitropaki & Martin, 1999) than transformational leadership. Hence, it can be expected that:

-

H2a: High-quality LMX will mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and the multidimensional construct of employee well-being.

LMX as a Mediator Between Ethical Leadership and Employee Well-Being

By showing trust in the subordinates (Brown & Treviño, 2006), treating them fairly and objectively, and maintaining good ties (Walumbwa et al., 2011), ethical leaders make them satisfied and more engaged in their job. In high-quality LMX, employees receive trust, respect, support, fair treatment, openness, and honesty (Graen & Scandura, 1987) from the ethical leader. The association of high-quality LMX with positive and negative dimensions of well-being has already been established (Sparks, 2012). Hence, it can be hypothesized that:

-

H2b: High-quality LMX will mediate the relationship between ethical leadership and the multidimensional construct of employee well-being.

LMX as a Mediator Between Empowering Leadership and Employee Well-Being

Empowering leaders nurture high-quality relationships with their subordinates (Gao et al., 2011) by displaying trust in and care for the subordinates (Ahearne et al., 2005), which fosters employee job satisfaction and engagement. Furthermore, empowering leaders, by delegating decision-making authority (Hassan et al., 2013) and sharing power or responsibility and autonomy with subordinates (Srivastava et al., 2006), develop reciprocal and long-term exchange relationships with employees. As it has previously been demonstrated that high-quality LMX is associated with both positive and negative dimensions of well-being, it can be expected that:

-

H2c: High-quality LMX will mediate the relationship between empowering leadership and the multidimensional construct of employee well-being.

LMX as a Mediator Between Servant Leadership and Employee Well-Being

Servant leaders establish high-quality LMX by focusing on the personal growth of the subordinates and providing opportunities to acquire new skills (Liden et al., 2014), and by seeking their ideas and encouraging them to participate in decision-making (Hunter et al., 2013). Furthermore, by putting subordinates’ needs first, servant leaders provide tangible and intangible resources to subordinates to satisfy their working needs (Liden et al., 2008). Hence, servant leaders, through high-quality LMX relationships are expected to result in high levels of well-being of the subordinates. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that:

-

H2d: High-quality LMX will mediate the relationship between servant leadership and the multidimensional construct of employee well-being.

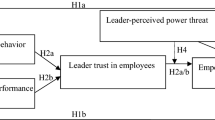

The direct and indirect relationship of different leadership styles individually with different dimensions of employee well-being through many mediating pathways have already been examined in earlier research (Inceoglu et al., 2018). This study attempts to extend such literature by comparing the relative importance of transformational, ethical, empowering, and servant leadership in engendering employee well-being as manifested in multiple dimensions of job satisfaction, job engagement, job stress, and sleep quality. Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model. A time-lagged design allows for more rigorous testing of the direct and indirect associations between proposed leadership styles and employee well-being through LMX over time instead of a cross-sectional design (Inceoglu et al., 2018). Hence, this study proposes the use of a time-lagged approach.

Method

Participants

Five hundred and sixty middle-level managers working in eight private sector banking and insurance companies in the Indian states of Odisha and West Bengal participated in the study. Middle-level managers were selected for this study because they are unhappier than the lower and senior managers due to the nature of the role and associated demands (Zenger & Folkman, 2014). They experience depression and anxiety while shielding their subordinates from the excessive expectations of top management (Gjerde & Alvesson, 2020; Prins et al., 2015) and balancing the competing demands and aspirations of the top and bottom levels. Of the participants, 59% were males (M = 35.92 years, SD = 5.87) and 41% were female, 68% were married, 58% were postgraduates, with mean years of experience of 9.69 years (SD = 6.11), and mean years of association with the current supervisor was 3.78 years (SD = 1.74).

Survey Instrument

The survey instrument included scales for all the independent, dependent, and mediating variables along with questions on sociodemographic information. Though there are many scales available to measure the constructs of this study, only standard scales whose reliability and validity have been examined and established in previous studies were used.

Transformational Leadership

The multifactor leadership questionnaire (MLQ-6S) was used to assess transformational leadership (Bass & Avolio, 1990). MLQ-6S includes 12 behavioral items that measure the four dimensions: intellectual stimulation, idealized influence, individualized consideration, and inspirational motivation on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (frequently, if not always). In this study, the four dimensions were combined into a composite measure of TFL. A sample item includes, “My supervisor talks optimistically about the future.”

Ethical Leadership

The ten-item ethical leadership scale (Brown et al., 2005) was used to assess ethical leadership. All the items were measured on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item includes, “My supervisor can be trusted.”

Empowering Leadership

Ahearne et al.’s (2005) 12-item measure was used to assess empowering leadership. The scale has four sub-scales (enhancing the meaningfulness of work, fostering participation in decision-making, expressing confidence in high performance, and providing autonomy from bureaucratic constraints). All the items were measured on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item includes, “My manager allows me to do my job my way.” Like TFL, four subscales were combined into a composite measure of empowering leadership.

Servant Leadership

The seven-item measure of global servant leadership (SL-7; Liden et al., 2015) assessed servant leadership. All the items were measured on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item includes, “My leader puts my best interests ahead of his/her own.”

Leader-Member Exchange

The 12-item scale of Liden & Maslyn (1998) was used to measure LMX. All the items were measured on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item includes, “My supervisor is a lot of fun to work with.”

Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction was assessed using the 5-item Brief Job Satisfaction Measure II (Judge et al., 1998). The measure has two reverse-scored items. All the items were measured on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item includes, “I feel fairly satisfied with my present job.”

Job Engagement

The nine-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9; Schaufeli et al., 2006) was used to assess the job engagement of the executives. The three sub-dimensions of job engagement: vigor, dedication, and absorption, were combined to create a composite measure of job engagement. All items were measured on a seven-point scale of 0 (Never) to 6 (Always). A sample item includes, “I am immersed in my work.”

Job Stress

We assessed the job stress of the executives by a four-item scale (Keller, 1984). Two positive and two reversed keyed items were rated on a five-point scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample positive keyed item was, “I experience tension from my job”, and a sample reversed keyed item was, “There is no strain from working in my job.”

Sleep Quality

We assessed executives’ sleep quality using the four-item sleep quality subscale of the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire (Åkerstedt et al., 2002). The items were measured on a five-point response scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The higher the score, the lower the sleep quality. The composite score was reverse coded. Sample items include “Difficulties falling asleep in last three months” and “Premature awakenings in last three months.”

Employee Well-Being

Employee well-being was a higher-order latent variable measured with four lower-order factors: job satisfaction, job engagement, job stress, and sleep quality. The loadings of the lower-order latent variables to the higher-order latent variable were substantive and statistically significant (See Table 1), which indicates the quality of the employee well-being construct.

Control Variables

Literature shows that subordinate’s gender, age, and tenure with the leader (Arnold et al., 2007; Kalshoven & Boon, 2012; Wilks & Neto, 2013) also influence employee well-being. Therefore, to reduce spurious results and increase accuracy, we included gender (1 = female, 2 = male), age (in years), and tenure with the leader (in years) as control variables in the model.

Procedure

Researchers contacted the head of HR departments for permission to collect data and obtained the list of all middle-level managers working in each organization. From the list, only 800 (100 from each organization) managers were randomly (using a random number generator) selected and were contacted for data collection. Data were collected using an online survey at two time points (T1 and T2) to avoid common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2012). The time difference from T1 to T2 was six months. During those six months, the organizations had not undergone any major changes that could have affected employee well-being. During T1, randomly selected 800 managers were provided with the online survey link, which included an informed consent form. Out of 800 managers, only 720 responded (90% response rate) to the survey in T1. In T2, all the 720 managers who participated in T1 were again invited to the survey, but only 560 managers participated, resulting in a 78% response rate. The drop in the number of managers from T1 to T2 may be attributed to resignations or job switch of the managers after T1 or the voluntary nature of the survey. Therefore, nonresponse bias is less of an issue because of the high response rates (Schmidt & Pohler, 2018). Also, considering the data was collected in two-time points, nonresponse bias tests were conducted to compare the demographic variables, including gender, age, and tenure with the leader, between the employees who participated in the survey in both the time points (Armstrong & Overton, 1977). The results suggest no significant differences (p > 0.05). Managers in the T1 were coded based on their e-mail id to identify and match their respective responses from T2. All the leadership styles were assessed during T1. LMX, job satisfaction, job engagement, job stress, and sleep quality were assessed during T2. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Rajagiri Business School, Kochi, India.

Results

For testing the structure of employee well-being and the measurement model, confirmatory factor analysis was run using MPlus (Version 8; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). The confirmatory factor analytic evidence advocated a hierarchical structure comprising a higher-order employee well-being factor and four lower-order factors (job satisfaction, job engagement, job stress, and sleep quality). The lower-order factors emerged from the higher-order construct of employee well-being. In the hierarchical structure, the standardized loadings of job satisfaction to its items, job engagement to its items, job stress to its items, and sleep quality ranged from 0.70 to 0.80, 0.65–0.83, 0.73–0.81, and 0.65–0.82, respectively. The lower-order factors had substantial loadings on the higher-order factor of employee well-being, and the hierarchical structure showed a good fit to the data. The measurement model suggested that high employee well-being was generated from high job engagement, high job satisfaction, moderate sleep quality, and low job stress (See Table 1). The important trigger for employee well-being was job engagement.

To test the measurement model and the hypothesized model, the maximum-likelihood method of covariance-based structural equation modeling was applied using MPlus. The measurement model showed acceptable fit (χ2/df = 2.59, TLI = 0.86, CFI = 0.87, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06). The fit indices were acceptable as per the traditional cut-off criteria (CFI and TLI > 0.90, SRMR and RMSEA < 0.08) proposed by Kline (2016), as well as the more restrictive criteria (CFI and TLI > 0.95, SRMR and RMSEA < 0.06) proposed by Hu and Bentler (1999). Each construct had acceptable convergent validity (average variance extracted) and composite reliability (see Table 2). Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) criterion has a higher specificity and sensitivity rate (> 95%) compared to the Fornell-Larcker criterion and was therefore used for assessing discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015). The HTMT ratio of correlations among the constructs is presented in the upper diagonal portion of Table 2. The HTMT ratio of correlations was below the most liberal threshold of 0.90 and the conservative threshold of 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015), suggesting discriminant validity of all the constructs.

Though data were collected in two-time points, common method variance could not be ruled out because both the mediating variable (LMX) and the dependent variables were measured in Time 2. Hence, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted using both exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. In exploratory factor analysis, the single factor explained 37.50% of the variance, which was below the threshold of 50% (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In confirmatory factor analysis, the single factor hypothesized model did not fit the data well (χ2/df = 7.94, TLI = 0.45, CFI = 0.47, RMSEA = 0.11, SRMR = 0.11), confirming the non-existence of common method variance (Malhotra et al., 2006).

Hypothesis Testing

Table 3 presents the direct and indirect relationship of transformational, ethical, empowering, and servant leadership with employee well-being. The direct association of transformational (β = 0.12, p < 0.036), empowering (β = 0.12, p < 0.050), and servant (β = 0.07, p < 0.038) leadership with the multidimensional construct of employee well-being were positive and statistically significant. However, ethical leadership (β = 0.13, p < 0.085) was not significantly associated with subjective well-being. Hence, hypotheses H1a, H1c, and H1d were supported, and H1b was not supported. The relationship between transformational leadership and employee well-being was the strongest. The direct association of transformational (β = 0.47, p < 0.001), ethical (β = 0.24, p < 0.001), and empowering (β = 0.20, p < 0.001) leadership with LMX were also positive and statistically significant. However, servant leadership (β = 0.01, p < 0.705) was not significantly associated with subjective well-being.

The same model was also used to find the indirect relations of transformational, ethical, empowering, and servant leadership with employee well-being through LMX simultaneously. The indirect relation of transformational leadership (β = 0.19, p < 0.001), ethical leadership (β = 0.14, p < 0.001), and empowering leadership (β = 0.09, p < 0.001) with employee well-being through LMX were positive and statistically significant. Hence, hypotheses H2a, H2b, and H2c were supported. Refuting H2d, LMX did not mediate the relationship of servant leadership with employee well-being (β = 0.00, p = ns). Transformational leadership was strongly associated with employee well-being through LMX, followed by ethical and empowering leadership.

Discussion

This study is a unique attempt to validate the multidimensional construct of employee well-being and examine the relative importance of different leadership styles fostering employee well-being via LMX. The hierarchical structure of employee well-being comprising a higher-order employee well-being factor and the four lower-order factors of job satisfaction, job engagement, job stress, and sleep quality explains the employee well-being well. Transformational leadership showed the strongest direct and indirect association with employee well-being.

In this study, the multidimensional construct of employee well-being addressed the long-standing demand (Danna & Griffin, 1999; Inceoglu et al., 2018; Grant et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2015) for a multidimensional understanding of employee well-being. The higher-order factor of employee well-being accounted for the relationships among the four lower-order factors of job satisfaction (hedonic), job engagement (eudaimonic), job stress (negative), and sleep quality (physical; Page & Vella-Brodrick 2009). The lower-order factors emerged from the higher-order construct of employee well-being. This study reaffirms Busseri’s (2015) findings that the hierarchical structure explains the data on four components of employee well-being well. The four components are interdependent or related. When the four components of employee well-being are assessed using reliable measures, they can be successfully integrated into a hierarchical structure of employee well-being that maintains the theoretical distinctions between the hedonic, eudaimonic, negative, and physical dimensions of well-being. The findings of this study supported the proposed hierarchical model of employee well-being of banking and insurance sector employees. Employee well-being combines high job engagement, high job satisfaction, moderate sleep quality, and low job stress. Job engagement is the most important trigger for employee well-being. This result provides an important step in establishing a theoretically grounded and empirically validated taxonomy of employee well-being.

Our findings support the direct association between transformational, empowering, and servant leadership and employee well-being. Transformational leaders enhance job satisfaction and reduce the job stress of their subordinates (Liu et al., 2010). Leaders with idealized influence are motivated by their moral commitment to their subordinates, sacrifice short-term monetary rewards, and focus on their subordinates’ long-term health and well-being (Kelloway et al., 2012). Through inspirational motivation (Turner et al., 2002) and mentoring (Sosik & Godshalk, 2000), the subordinates experience low perceived stress at work and fewer stress symptoms. Intellectually stimulating leaders empower and give confidence to subordinates to enhance and safeguard their well-being (Sivanathan et al., 2012). Empathy, compassion, and guidance from considerate leaders enhance subordinates’ job satisfaction and job engagement (Arnold et al., 2007). Finally, empowering leaders by helping subordinates understand the significance of their work and involving them in decision-making enhances subordinates’ job satisfaction (Vecchio et al., 2010), job engagement (Gyu Park et al., 2017), well-being (Marin-Garcia & Bonavia, 2021), and reduce their psychological distress (Fitzsimons & Fuller, 2002).

Similarly, servant leaders enhance subordinates’ well-being by placing employee needs before the organizational needs, showing empathy, humility, and authenticity (van Dierendonck et al., 2004; Dierendonck et al., 2009). Servant leaders understand the needs of their subordinates and are therefore more likely to address their basic psychological needs, which ultimately enhance subordinates’ well-being. However, ethical leadership did not directly relate to employee well-being. A plausible explanation for this is the ethical incongruence between the ethical leader and the subordinates. When subordinates’ ethical position does not match their leaders’, they might feel pressure, adversely impacting their workplace well-being (Yang, 2014). When working under ethical leaders, employees feel the increased expectations for ethical behaviors such as assisting colleagues and other organizational and external stakeholders might hamper their well-being (Fu et al., 2020). This could be another explanation for why there was no direct association between ethical leadership and employee well-being.

The findings of this research also support the hypothesized mediating role of LMX between leadership styles (except servant leadership) and employee well-being. Transformational, ethical, and empowering leaders build high-quality exchange relationships and exchange resources with their subordinates. High-quality LMX is a job resource (Huell et al., 2016) that provides employees with social support to adapt better to their job demands (Thomas & Lankau, 2009). A good relationship with either a transformational, ethical or empowering supervisor will reduce negative work pressures (e.g., job stress, time pressure) and thus protect against ill-health (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Extant research has established that in-group employees with high-quality LMX relationships feel they are accepted, valued, motivated, and less stressed (Lagace et al., 1993), have control at work (Sparr & Sonnentag, 2008), and have occupational self-efficacy (Schyns et al., 2005). Through high-quality LMX relationships, leaders accommodate work-family needs and foster employee well-being (Hill et al., 2016). High-quality LMX relationship also enhances psychological capital, which in turn engenders both life and job satisfaction of employees (Liao et al., 2017), psychological well-being (Huell et al., 2016), work-related well-being, and reduces job stress (Sonnentag & Pundt, 2014).

But servant leadership did not associate with employee well-being through LMX. A possible explanation is that servant leaders treat all subordinates equally and form good relationships with all (Liden et al., 2008) instead of forming high- and low-quality relationships with all subordinates due to the limited resources at their disposal (Eva et al., 2019). Servant leadership had a direct association with employee well-being. Like servant leadership, LMX does not provide personal healing and help grow subordinates into servant leaders (Liden et al., 2008). This might be another reason why servant leadership had no indirect relationship with employee well-being via LMX.

Transformational leaders enrich the quality of relationships with their subordinates through personal interaction (Wang et al., 2005), and such high-quality relationships engender employee well-being (van Dierendonck et al., 2004). Empowering leaders by displaying trust in subordinates’ ability to make decisions and reducing bureaucratic constraints fosters high-quality relationships (Ahearne et al., 2005). Consequently, such high-quality relationships improve job engagement, higher occupational self-efficacy, and greater psychological well-being of the subordinates (Huell et al., 2016). Honest and trustworthy ethical leaders make fair and righteous decisions and show concern for the welfare of those subordinates who are the members of the in-groups (Brown & Treviño, 2006; Brown et al., 2005). Ethical leaders’ display of care and concern fosters emotional connectedness and mutual support, which creates the ground for high-quality LMX (Erdogan et al., 2006).

Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study add to the leadership and employee well-being literature and provide evidence for the prominence of transformational leadership among the different leadership styles in enhancing employee well-being. The validation of the hierarchical structure of employee well-being lends empirical support to the ongoing discourse on the multidimensional nature of employee well-being construct and adds to the employee well-being literature. The findings also contribute to the understanding of the differential effects of different leadership styles, notably, the inverse relationship between ethical leadership and employee well-being. Thus, findings contribute to the evidence on ethical incongruence between the ethical leader and the subordinates (Yang, 2014). The role of LMX as an intervening mechanism between different leadership styles and the multidimensional construct of employee well-being is also established. Thus, LMX is found to act as a mechanism for enhancing the effects of transformational, ethical, and empowering leadership, except for servant leadership on employee well-being. Such findings also add to our understanding that servant leaders do not distinguish among subordinates and hence fail to form high- and low-quality relationships.

Practical Implications

This study also offers a few practical implications. First, leaders can be trained to understand the multi-faceted nature of employee well-being and how their leadership style affects these through the quality of their relationships with employees. Second, they can be trained to employ specific leadership behaviors at work, leading to high-quality LMX, which will enhance employee well-being. Third, ethical leaders may be trained to prevent the adverse effects on employee well-being due to increased expectations for ethically congruent behaviors. Finally, transformational, ethical, and empowering leaders can be encouraged to build high-quality relationships with their subordinates so that their employees can make the most of the leadership styles.

Limitations and Future Scope

Notwithstanding the contributions, this study has a few limitations. First, the research sample consisted of workers employed in Indian private banking and insurance sector organizations. Therefore, the findings of this study should be extended to other sectors in India and other cultures with caution. Second, though a time-lagged design was adopted, the data were obtained from the subordinates only (common method variance) for all the constructs, which might have increased the likelihood of inflated outcomes. Future researchers can consider collecting data from multiple sources like leaders and subordinates and incorporate multi-level analysis to include both team and organizational levels to find out other possible antecedents of employee well-being. Third, only the hierarchical structure of employee well-being was tested. Researchers can test various structures (separate components, hierarchical, causal, and composite) of employee well-being. Fourth, leadership styles other than transformational, ethical, empowering, and servant leadership styles can be used and compared to find potent predictors of employee well-being in future research. Other indicators of hedonic, eudaimonic, negative, and physical well-being can be used to test the multidimensional nature and hierarchical structure of employee well-being. Furthermore, future studies might consider other mediators to see the mechanism through which different leadership styles engender employee well-being. Finally, the time-lagged design does not make the findings support causality (Nelson et al., 2014). Hence the cross-lagged approach is recommended to establish causality (Anderson & Kida, 1982).

Conclusions

This study contributes to our understanding of employee well-being as a higher-order multidimensional construct composed of four lower-order constructs: job satisfaction, job engagement, job stress, and sleep quality. This study also validates the hierarchical structure of employee well-being. In addition, this study also provides evidence that transformational leadership is the most potent predictor of employee well-being, followed by empowering leadership. No direct association between ethical leadership and employee well-being emphasized that the leaders’ expectation of ethical behaviors put subordinates under stress and hamper their well-being. The indirect relationship between servant leadership and employee well-being through LMX highlighted that servant leaders fail to develop high-quality LMX with their subordinates. Hence, transformational, ethical, and empowering leaders can be encouraged to build high-quality relationships with their subordinates to enhance their well-being. Especially ethical leaders can be cautioned against expecting ethically congruent behaviors from their subordinates to help protect their well-being.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahearne, M., Mathieu, J., & Rapp, A. (2005). To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 945–955. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.945

Åkerstedt, T., Knutsson, A., Westerholm, P., Theorell, T., Alfredsson, L., & Kecklund, G. (2002). Sleep disturbances, work stress and work hours. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(3), 741–748. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00333-1

Anderson, T. N., Jr., & Kida, T. E. (1982). The cross-lagged research approach: Description and illustration. Journal of Accounting Research, 20(2), 403–414. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490748

Andrews, M., & Kacmar, K. M. (2014). Easing employee strain: The interactive effects of empowerment and justice on the role overload-strain relationship. Journal of Behavioral & Applied Management, 15(2), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.21818/001c.17937

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150783

Arnold, J. A., Arad, S., Rhoades, J. A., & Drasgow, F. (2000). The empowering leadership questionnaire: The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring leader behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(3), 249–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379)21:3%3C249::AID-JOB10%3E3.0.CO;2-%23

Arnold, K. A. (2017). Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000062

Arnold, K. A., Connelly, K. E., Walsh, M. M., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2015). Leadership styles, emotion regulation, and burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4), 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039045

Arnold, K. A., Turner, N., Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., & McKee, M. C. (2007). Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: The mediating role of meaningful work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.193

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2011). Subjective well-being in organizations. In The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship (pp. 178–189)

Barling, J., Christie, A., & Hoption, C. (2010). Leadership. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. American Psychological Association

Barnes, C. M., Awtrey, E., Lucianetti, L., & Spreitzer, G. (2020). Leader sleep devaluation, employee sleep, and unethical behavior. Sleep Health, 6(3), 411–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2019.12.001

Bartels, A. L., Peterson, S. J., & Reina, C. S. (2019). Understanding well-being at work: Development and validation of the eudaimonic workplace well-being scale. PLoS One1, 14(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215957

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1990). Developing transformational leadership: 1992 and beyond. Journal of European Industrial Training, 14(5), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090599010135122

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Sage

Berger, R., Czakert, J. P., Leuteritz, J. P., & Leiva, D. (2019). How and when do leaders influence employees’ well-being? Moderated mediation models for job demands and resources. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02788

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley

Boer, D., Deinert, A., Homan, A. C., & Voelpel, S. C. (2016). Revisiting the mediating role of leader-member exchange in transformational leadership: The differential impact model. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(6), 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1170007

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

Bryson, A., Forth, J., & Stokes, L. (2017). Does employees’ subjective well-being affect workplace performance? Human Relations, 70(8), 1017–1037. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717693073

Busseri, M. A. (2015). Toward a resolution of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being. Journal of Personality, 83(4), 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12116

Busseri, M. A. (2018). Examining the structure of subjective well-being through meta-analysis of the associations among positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 122(1), 68–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.003

Carter, D., & Baghurst, T. (2014). The influence of servant leadership on restaurant employee engagement. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(3), 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1882-0

Chen, C. Y., Chen, C. H. V., & Li, C. I. (2013). The influence of leader’s spiritual values of servant leadership on employee motivational autonomy and eudaimonic well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(2), 418–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9479-3

Chughtai, A., Byrne, M., & Flood, B. (2015). Linking ethical leadership to employee well-being: The role of trust in supervisor. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2126-7

Cicero, L., & Pierro, A. (2007). Charismatic leadership and organizational outcomes: The mediating role of employees’ work-group identification. International Journal of Psychology, 42(5), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701248495

Coetzer, M. F., Bussin, M. H., & Geldenhuys, M. (2017). Servant leadership and work-related well-being in a construction company. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 43(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v43i0.1478

Dagar, C., & Pandey, A. (2021). Well-Being at workplace: A perspective from traditions of Yoga and Ayurveda. In S. Dhiman (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of workplace well-being (pp. 1237–1264). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30025-8_46

Danna, K., & Griffin, R. W. (1999). Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management, 25(3), 357–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500305

De Hoogh, A. H. B., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2008). Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader’s social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates’ optimism: A multi-method study. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(3), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.03.002

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation (pp. 85–107). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0006

Di Fabio, A. (2017). The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(SEP), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01534

Diener, E., & Chan, M. Y. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x

Diener, E., Heintzelman, S. J., Kushlev, K., Tay, L., Wirtz, D., Lutes, L. D., & Oishi, S. (2017). Findings all psychologists should know from the new science on subjective well-being. Canadian Psychology, 58(2), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000063

Diener, E., Sandvik, E., Pavot, W., & Gallagher, D. (1991). Response artifacts in the measurement of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00292649

Diener, E., Sapyta, J. J., & Suh, E. (1998). Subjective well-being is essential to well-being. Psychological Inquiry, 9(1), 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0901_3

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Epitropaki, O., & Martin, R. (1999). The impact of relational demography on the quality of leader-member exchanges and employees’ work attitudes and well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72(2), 237–240. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317999166635

Erdogan, B., Liden, R. C., & Kraimer, M. L. (2006). Justice and leader-member exchange: The moderating role of organizational culture. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20786086

Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., van Dierendonck, D., & Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004

Fitzsimons, S., & Fuller, R. (2002). Empowerment and its implications for clinical practice in mental health: A review. Journal of Mental Health, 11(5), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230020023

Fu, J., Long, Y., He, Q., & Liu, Y. (2020). Can ethical leadership improve employees’ well-being at work? Another side of ethical leadership based on organizational citizenship anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01478

Gao, L., Janssen, O., & Shi, K. (2011). Leader trust and employee voice: The moderating role of empowering leader behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(4), 787–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.05.015

Gilbert, S. L., & Kelloway, E. K. (2014). Leadership. In M. Gagné (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and self-determination theory (pp. 181–198). Oxford University Press

Gjerde, S., & Alvesson, M. (2020). Sandwiched: Exploring role and identity of middle managers in the genuine middle. Human Relations, 73(1), 124–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718823243

Goldman, A., & Tabak, N. (2010). Perception of ethical climate and its relationship to nurses’ demographic characteristics and job satisfaction. Nursing Ethics, 17(2), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733009352048

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

Graen, G. B., & Scandura, T. A. (1987). Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. In B. M. Staw, & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (pp. 175–208). JAI Press

Grant, A. M., Christianson, M. K., & Price, R. H. (2007). Happiness, health, or relationships? Managerial practices and employee well-being tradeoffs. Academy of Management Perspectives, 21(3), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2007.26421238

Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership. Paulist Press

Greenleaf, R. K. (1998). The power of servant leadership. Berrett-Koehler Publishers

Guest, D. E. (2017). Human resource management and employee well-being: Towards a new analytic framework. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12139

Gyu Park, J., Kim, S., Joo, J., & Yoon, S. (2017). The effects of empowering leadership on psychological well-being and job engagement. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(3), 350–367. https://doi.org/10.1108/lodj-08-2015-0182

Harris, K. J., & Kacmar, K. M. (2006). Too much of a good thing: The curvilinear effect of leader-member exchange on stress. Journal of Social Psychology, 146(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.146.1.65-84

Hassan, S., Mahsud, R., Yukl, G., & Prussia, G. E. (2013). Ethical and empowering leadership and leader effectiveness. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 28(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941311300252

Henderson, D. J., Liden, R. C., Glibkowski, B. C., & Chaudhry, A. (2009). LMX differentiation: A multilevel review and examination of its antecedents and outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(4), 517–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.04.003

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hill, R. T., Morganson, V. J., Matthews, R. A., & Atkinson, T. P. (2016). LMX, breach perceptions, work-family conflict, and well-being: A mediational model. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 150(1), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2015.1014307

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037//1089-2680.6.4.307

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In S. Folkman (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping (pp. 127–147). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195375343.013.0007

Hochwarter, W. (2005). LMX and job tension: Linear and non-linear effects and affectivity. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19(4), 505–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-005-4522-6

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huell, F., Vincent-Höper, S., Bürkner, P. C., Gregersen, S., Holling, H., & Nienhaus, A. (2016). Leader-member exchange and employee well-being: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2016(1), 13537. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2016.13537abstract

Hunter, E. M., Neubert, M. J., Perry, S. J., Witt, L. A., Penney, L. M., & Weinberger, E. (2013). Servant leaders inspire servant followers: Antecedents and outcomes for employees and the organization. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(2), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.12.001

Inceoglu, I., Chu, C., Plans, D., & Gerbasi, A. (2018). Leadership behavior and employee well-being: An integrated review and a future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.12.006

International Labour Organization (2022). Workplace well-being. Author. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/areasofwork/workplace-health-promotion-and-well-being/WCMS_118396/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 4 Mar 2022

Jaramillo, F., Grisaffe, D. B., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2009). Examining the impact of servant leadership on sales force performance. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 29(3), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.2753/pss0885-3134290304

Judge, T. A., & Colquitt, J. A. (2004). Organizational justice and stress: The mediating role of work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 395–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.395

Judge, T. A., Locke, E. A., Durham, C. C., & Kluger, A. N. (1998). Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.1.17

Kalshoven, K., & Boon, C. T. (2012). Ethical leadership, employee well-being, and helping the moderating role of human resource management. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 11(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000056

Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D. N., & De Hoogh, A. H. B. (2011). Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.007

Keeman, A., Näswall, K., Malinen, S., & Kuntz, J. (2017). Employee wellbeing: Evaluating a wellbeing intervention in two settings. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(MAR), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00505

Keller, R. T. (1984). The role of performance and absenteeism in the prediction of turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 27(1), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.5465/255965

Kelloway, E. K., Turner, N., Barling, J., & Loughlin, C. (2012). Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: The mediating role of employee trust in leadership. Work and Stress, 26(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2012.660774

Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2018). Can empowering leaders affect subordinates’ well-being and careers because they encourage subordinates’ job crafting behaviors? Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 25(2), 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/e506122017-001

Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2018). Organization-based self-esteem and meaningful work mediate effects of empowering leadership on employee behaviors and well-being. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 25(4), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051818762337

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press

Koh, H. C., & Boo, E. H. Y. (2004). Organisational ethics and employee satisfaction and commitment. Management Decision, 42(5), 677–693. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740410538514

Kun, A., & Gadanecz, P. (2019). Workplace happiness, well-being and their relationship with psychological capital: A study of Hungarian Teachers. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00550-0

Kuoppala, J., Lamminpää, A., Liira, J., & Vainio, H. (2008). Leadership, job well-being, and health effects – A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 50(8), 904–915. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e31817e918d

Lagace, R. R., Castleberry, S. B., & Ridnour, R. E. (1993). An exploratory salesforce study of the relationship between leader-member exchange and motivation, role stress, and manager evaluation. Journal of Applied Business Research, 9(4), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v9i4.6001

Liao, S. S., Hu, D. C., Chung, Y. C., & Chen, L. W. (2017). LMX and employee satisfaction: mediating effect of psychological capital. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 38(3), 433–449. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-12-2015-0275

Liden, R. C., & Graen, G. (1980). Generalizability of the vertical dyad linkage model of leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 23(3), 451–465. https://doi.org/10.2307/255511

Liden, R. C., & Maslyn, J. M. (1998). Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. Journal of Management, 24(1), 43–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2063(99)80053-1

Liden, R. C., Panaccio, A., Meuser, J. D., Hu, J., & Wayne, S. J. (2014). Servant leadership: Antecedents, processes, and outcomes. In D. V. Day (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations (pp. 357–379). Oxford University Press

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Meuser, J. D., Hu, J., Wu, J., & Liao, C. (2015). Servant leadership: Validation of a short form of the SL-28. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.12.002

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., & Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006

Liu, J., Siu, O. L., & Shi, K. (2010). Transformational leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of trust in the leader and self-efficacy. Applied Psychology An International Review, 59(3), 454–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00407.x

Luthans, F., & Avolio, B. J. (2003). Authentic leadership: A positive developmental approach. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 241–261). Barrett-Koehler

Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., & Patil, A. (2006). Common method variance in IS research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Management Science, 52(12), 1865–1883. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0597

Marin-Garcia, J. A., & Bonavia, T. (2021). Empowerment and employee well-being: A mediation analysis study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115822

Mayer, D. M., Bardes, M., & Piccolo, R. F. (2008). Do servant-leaders help satisfy follower needs? An organizational justice perspective. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 17(2), 180–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320701743558

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th Edition). Author

Nelson, K., Boudrias, J. S., Brunet, L., Morin, D., De Civita, M., Savoie, A., & Alderson, M. (2014). Authentic leadership and psychological well-being at work of nurses: The mediating role of work climate at the individual level of analysis. Burnout Research, 1(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2014.08.001

Ng, T. W. (2017). Transformational leadership and performance outcomes: Analyses of multiple mediation pathways. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(3), 385–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.11.008

O’Donnell, M., Yukl, G., & Taber, T. (2012). Leader behavior and LMX: A constructive replication. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941211199545

O’Donoghue, D., & van der Werff, L. (2021). Empowering leadership: Balancing self-determination and accountability for motivation. Personnel Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2019-0619

Page, K. M., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2009). The “what”, “why” and “how” of employee well-being: A new model. Social Indicators Research, 90(3), 441–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9270-3

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Prins, S. J., Bates, L. M., Keyes, K. M., & Muntaner, C. (2015). Anxious? Depressed? You might be suffering from capitalism: Contradictory class locations and the prevalence of depression and anxiety in the USA. Sociology of health & illness, 37(8), 1352–1372. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12315

Rahimnia, F., & Sharifirad, M. S. (2014). Authentic leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of attachment insecurity. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(2), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2318-1

Resick, C. J., Hanges, P. J., Dickson, M. W., & Mitchelson, J. K. (2006). A cross-cultural examination of the endorsement of ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(4), 345–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-3242-1

Rockstuhl, T., Dulebohn, J. H., Ang, S., & Shore, L. M. (2012). Leader–member exchange (LMX) and culture: A meta-analysis of correlates of LMX across 23 countries. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1097–1130. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029978

Rothmann, S. (2008). Job satisfaction, occupational stress, burnout and work engagement as components of work-related wellbeing. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 34(3), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v34i3.424

Russell, J. E. A. (2008). Promoting subjective well-being at work. Journal of Career Assessment, 16(1), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707308142

Schaubroeck, J., Lam, S. S. K., & Peng, A. C. (2011). Cognition-based and affective-based trust as mediators of leader behavior influence on team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 863–871. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022625

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Schmidt, J. A., & Pohler, D. M. (2018). Making stronger causal inferences: Accounting for selection bias in associations between high performance work systems, leadership, and employee and customer satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(9), 1001–1018. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000315

Schyns, B., Paul, T., Mohr, G., & Blank, H. (2005). Comparing antecedents and consequences of leader–member exchange in a German working context to findings in the US. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 14(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320444000191

Sianoja, M., Crain, T. L., Hammer, L. B., Bodner, T., Brockwood, K. J., LoPresti, M., & Shea, S. A. (2020). The relationship between leadership support and employee sleep. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 25(3), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000173

Sivanathan, N., Arnold, K. A., Turner, N., & Barling, J. (2012). Leading well: Transformational leadership and well-being. In P. A. Linley, & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive Psychology in Practice (pp. 241–255). Wiley

Skakon, J., Nielsen, K., Borg, V., & Guzman, J. (2010). Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work and Stress, 24(2), 107–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2010.495262

Sonnentag, S., & Pundt, A. (2014). Leader-member exchange from a job stress perspective. In T. N. Bauer & B. Erdogan (Eds.), Oxford handbook of leader-member exchange (pp. 1–23). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199326174.013.0011

Sosik, J. J., & Godshalk, V. M. (2000). Leadership styles, mentoring functions received, and Job-related stress: A conceptual model and preliminary study. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 21(4), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-1379(200006)21:4<365::aid-job14>3.0.co;2-h

Sparks, T. E. (2012). Ethical and unethical leadership and followers’ well-being: Exploring psychological processes and boundary conditions (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Georgia, Athens). Retrieved from https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/sparks_taylor_e_201205_phd.pdf. Accessed 18 Feb 2022

Sparr, J. L., & Sonnentag, S. (2008). Fairness perceptions of supervisor feedback, LMX, and employee well-being at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 17(2), 198–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320701743590

Sparrowe, R. T., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Process and structure in leader-member exchange. The Academy of Management Review, 22(2), 522–552. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707154068

Srivastava, A., Bartol, K. M., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Empowering leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1239–1251. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.23478718

Suar, D., Jha, A. K., Das, S. S., & Alat, P. (2019). The structure and predictors of subjective well-being among millennials in India. Cogent Psychology, 6(1), 1584083. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1584083

Thomas, C. H., & Lankau, M. J. (2009). Preventing burnout: The effects of LMX and mentoring on socialization, role stress, and burnout. Human Resource Management, 48(3), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20288

Turner, N., Barling, J., & Zacharatos, A. (2002). Positive psychology at work. In C. R. Snyder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 715–728). Oxford University Press

United Nations (2015). Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from: http://www.Un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

van Dierendonck, D., Haynes, C., Borrill, C., & Stride, C. (2004). Leadership behavior and subordinate well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9(2), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.9.2.165

van Dierendonck, D., Nuijten, I., & Heeren, I. (2009). Servant leadership, key to follower well-being. In D. Tjosvold, & B. Wisse (Eds.), Power and interdependence in organizations (pp. 319–337). Cambridge University Press