Abstract

The self-expansion theory suggests that acquiring novel experiences, perspectives, and resources can expand people’s self-concepts (Aron & Aron, 1986). Many studies have demonstrated the implications of self-expansion for wellbeing in interpersonal and nonrelational contexts. Although scholars have proposed that self-expansion is a basic human motivation, research that supports its cross-cultural generalizability is limited. The present study aimed to contribute to the research (a) by validating a Chinese translation of the Self-Expansion Questionnaire (SEQ, Lewandowski & Aron, 2002) and the Individual Self-Expansion Questionnaire (ISEQ, Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2013)—the established measures of self-expansion in relational and nonrelational contexts, respectively; and (b) by assessing psychometric properties of a measure of the general self-expansion which modified and combined the SEQ and ISEQ. Study 1 conducted an online survey among 335 undergraduate students and examined the factor structures of the scales using exploratory factor analyses. Study 2 aimed to assess the scales among working adults (N = 327) and conducted a confirmatory factor analysis. Both the studies measured openness to experience, sensation seeking, and epistemic curiosity to test convergent validity of the self-expansion scales; and assessed their predictive validity by including self-efficacy, self-esteem, positive and negative affect, and life satisfaction. Findings of the two studies showed that the Chinese scales had good internal reliability and validity, suggesting their applicability to Chinese adult populations. We discussed possible differences in the self-expansion of Chinese and members of individualist cultures and provided questions for future research on general self-expansion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A person’s sense of “who I am” shifts throughout life. People can expand their sense of self by gaining novel perspectives, resources, and identities—a phenomena called self-expansion (Aron & Aron, 1986). When experiencing self-expanding events or relationships, people typically say that such experience broadens their horizons or makes them a better person. The self-expansion model (Aron & Aron, 1986; Aron, Lewandowski, Mashek, & Aron, 2013) proposes that humans have an innate motivation to add novel content to their self-concepts because a diverse and complex self-concept makes them feel competent. This model has been used to explain aspects of close relationships and other research areas (Aron et al., 2013), but most research has been conducted in the U.S. context. Self-expansion research in Chinese context is limited, partly due to a lack of valid measurement tools. Therefore, the present work aimed to validate a Chinese translation of established self-expansion scales. This may facilitate the relevant study in Chinese-speaking regions, providing evidence for the cross-cultural generalizability of the theory. Moreover, previous research has examined self-expansion in relational and nonrelational contexts separately, little is known about whether the general self-expansion experienced across life domains impacts one’s well-being. This study assessed the psychometric features of a composite measure of general self-expansion which adapted and combined the current scales. It might be applied in future research on general self-expansion.

Literature Review

Self-Expansion and its Importance for Relationship Well-Being

To understand self-expansion experience, it is helpful to consider questions of the Self-Expansion Questionnaire (SEQ, Lewandowski & Aron, 2002), such as “How much does being with your partner result in your having new experiences?”; “How much do you see your partner as a way to expand your own capabilities?”; and “How much do you feel that you have a larger perspective on things because of your partner?”. According to the self-expansion theory, in the context of romantic relationships, self-expansion enhances if a partner introduces an individual to novel experiences such as new places, friends, and activities, and if they share their financial and social resources; because these new experiences and resources are added to one’s self-concept (i.e., they become “mine”; Aron et al., 2013). Individuals can also mentally take on the personal traits and preferences of their partners through a process referred to as “including others in the self” (Aron et al., 1992).

Self-expansion research initially focused on romantic relationships and has since been applied to various relationship contexts such as initial attraction, starting a new relationship, maintaining an ongoing relationship, infidelity, and relationship dissolution (for reviews, see Aron et al., 2013; Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2014a). For example, the experience of early-stage romantic love is theorized to involve rapid self-expansion, as falling in love provides many opportunities to gain new experiences and expand the self; accordingly, research has shown that the breadth of an individual’s self-concept and evaluation of self-worth (self-esteem) and ability (self-efficacy) increases rapidly after falling in love (Aron, Paris, & Aron, 1995). As time passes, couples become familiar with each other, and routines are established, leading to less novelty in the relationships. However, consistent with the self-expansion theory, research has suggested that long-term partners can reduce boredom, gain more satisfaction, and enhance their feelings for each other (passionate love) by meeting the need for self-expansion in novel and interesting activities together (Aron et al., 2000) and by supporting each other’s individual self-expanding activities (Fivecoat et al., 2015).

Importance of Self-Expansion for Personal Well-Being

The self-expansion perspective has recently been applied to a broader range of topics such as group identity and intergroup relations, relationships with nature, brands, and consumption, and drug addiction (see Aron et al., 2013 for a review). These studies have provided evidence that close relationships are not the only source of self-expansion; other people and entities can also affect the self. For instance, a study has found that the self-expansion experienced at work predicts job satisfaction and affective commitment and losing a self-expanding job is associated with reduced self-esteem and clarity about the self (McIntyre et al., 2014).

Self-expansion can also occur through solitary activities (nonrelational self-expansion, see Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2014a) in addition to relationships. Research has shown that engaging in novel, interesting, and challenging activities on one’s own can provide new content for one’s self-concept and encourage personal growth (see Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2014a for review). Experiencing novel and interesting activities has been associated with larger self-concept size (Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2013, 2014b), greater self-efficacy, and putting more effort into subsequent tasks (Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2013). Overall, self-expansion can be achieved via different sources and may lead to positive outcomes in terms of relationships, health, and well-being. Nonrelational self-expansion is worth more research.

Current Measurements

The SEQ is a widely used measure of relational self-expansion, and it has been adapted to assess the self-expansion brought by other sources, such as friends and fictional characters (Shedlosky-Shoemaker et al., 2014) and jobs (McIntyre et al., 2014), simply by replacing the phrase “your partner” in the items with the target source (e.g., “your job”). The Individual Self-Expansion Questionnaire (ISEQ) was developed to measure self-expansion experienced through solitary activities (Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2013). Sample items include “Do you feel a greater awareness of things?” and “How much has doing the previous activity resulted in your learning new things?”.

The Inclusion of Others in the Self (IOS) scale (Aron et al., 1992) is another measure of relational self-expansion. The IOS consists of a single item made up of seven pairs of overlapping circles with increasing degrees of overlap; they range from two circles with no overlap to two circles with almost complete overlap. Respondents select the pair of circles that best represents their relationship with another person. Research has shown that if another is included in the self, the self-concepts of the two become interdependent and intertwined to the extent that one takes on the perspectives, identities, and resources of the other (Aron et al., 1992). This type of inclusion, however, is just one path to self-expansion. The IOS scale measures a combination of behavioral closeness (e.g., spending time together) and cognitive closeness (e.g., a greater sense of “we” than of “me” or “I”). An individual may have a high degree of inclusion and closeness with a boring partner who provides little self-expansion, just as a lower degree of inclusion with a dynamic partner who provides much self-expansion (see Aron et al., 2013, for a discussion).

Self-Expansion Research in the Chinese Context

Chinese research applying the self-expansion model is sparse, and most works are master’s theses (for reviews, see Jia & Shi, 2012; Lai et al., 2018). Several studies published in academic journals have used the IOS (e.g., Mao et al., 2019). The SEQ and ISEQ have not been properly translated and validated; although a few theses have used the SEQ, their Chinese version is not accurate (Cui, 2013; Jia, 2012; Pu, 2013). Therefore, it is important to validate the established scales to facilitate Chinese research on this topic.

Existing findings in the Chinese context regarding self-expansion in romantic relationships are consistent with those found in Western cultures. There is evidence that Chinese individuals expand their self-concepts through their partners, higher levels of self-expansion predicts relationship satisfaction (e.g., Jia, 2012) and jealousy (Pu, 2013), and the link between self-expansion and relationship outcomes is moderated by personality traits such as regulatory focus (Cui, 2013).

A few studies have explored self-expansion through other sources. For instance, the sense of self of Chinese rural children whose parents migrated to urban areas to work has been found to include a caregiving grandmother rather than a mother, which benefitted their academic and psychosocial development (Bi et al., 2020). The humility of leaders was found to predict the self-expansion of their followers, possibly because of the high levels of expected benefits and potential for expansion with the leaders, and this self-expansion then enhanced the self-efficacy and job performance of the followers (Mao et al., 2019). The self-expansion model has been applied to research on technology use (e.g., Liu, Huang, & Zhou, 2020; Niu, 2017). A study showed that the self-expansion achieved via Internet use was associated with reduced clarity and greater complexity of self-concept, and also predicted self-efficacy, life satisfaction, and reduced depression (Niu, 2017).

Our brief literature review demonstrates the value of self-expansion model for different areas of research in the Chinese context, conversely, Chinese research could contribute to the self-expansion literature. An assumption of the self-expansion theory is that self-expansion is a basic human motivation (e.g., Aron & Aron, 1986), therefore research suggests that people prefer relationships that bring new experiences and self-identities and losing such relationships leads to dissatisfaction and distress (for reviews, see Aron et al., 2013; Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2014a). If the motivation of self-expansion is indeed basic and universal, similar results should be found in studies across different cultures. Aron and colleagues (2013) proposed several directions for future research in their literature review, including exploring the potential moderating role of cultural contexts in the effects of self-expansion motivation.

The limited Chinese research generally supports the cross-cultural generalizability of the model, but more research is required to examine potential cultural differences because, according to cultural psychology, a culture influences the self-representations of its members (e.g., Markus & Kityama, 1991). Specifically, members of more collectivist cultures perceive the self as interconnected with others and strive to maintain their relationships and group memberships, whereas those in more individualist cultures view the self as independent from others and tend to protect their uniqueness and autonomy.

Chinese culture nurtures a fundamentally interdependent self-construal, and interpersonal relationships are crucial for self-concepts of Chinese people (Markus & Kityama, 1991). Therefore, they might have a greater motivation or preference for self-expansion. One study has found that the participants whose interdependent self-construal was activated demonstrated a greater motivation to include a new friend in their sense of themselves, compared with those whose independent self-construal was primed (Guo, 2011). The impact of self-expansion on close relationships might also vary across cultures. For example, a lack of self-expansion has been found to predict infidelity and relationship dissolution in individualist cultures (e.g., Lewandowski & Ackerman, 2006). However, as a long-term relationship represents a strong form of self-definition for Chinese people, they might find it more difficult to dissolve such a relationship, even if the opportunity for self-expansion is insufficient. Therefore, Chinese research may have important theoretical implications for the self-expansion research in general.

The Present Work

Our first aim was to translate and validate the SEQ and ISEQ to facilitate Chinese research on relational and nonrelational self-expansion, respectively. We followed the standard translation and back-translation procedure (Hambleton et al., 2004), and the scales were translated into Chinese by a professional native Chinese-speaking translator. The first author and the translator found that two items may be somewhat ambiguous for Chinese respondents and thus produced two alternatives for each to empirically determined the better version. The Chinese translation was tested in a pilot study to further improve the clarity and accuracy of the content, and it was then back-translated by a native English-speaking translator. The back-translation was approved by the developer of the scales. As self-expansion is universal, we expected to observe it in Chinese individuals and identify its associations with conceptually related variables and established outcomes. We thus hypothesized that the Chinese SEQ and ISEQ are unidimensional scales, and have good reliability, as well as convergent and predictive validity.

Second, previous studies consider the relational and nonrelational contexts separately, as they investigate the self-expanding experience acquired from one source and its effect on an individual’s behavior toward that source, such as through a partner and how it affects the relationship with that partner (Aron et al., 2013). To our knowledge, less research has assessed the general self-expansion one experiences in both contexts. However, it is reasonable to assume that such a general expansion level might have implications for life outcomes. To illustrate, self-expansion can be achieved through interesting work or solitary activities if a spouse ceases to provide such opportunities, the general self-expansion thus remains relatively high, which might protect the relationship. A study of long-term couples found that if one’s nonrelational self-expansion was supported by a partner, relationship satisfaction increased (Fivecoat et al., 2015), implying the importance of greater overall self-expansion. A study of drug addiction asked current and former smokers to report various self-expanding events and activities over the past two months (both relational and nonrelational), and a larger number of such events was associated with smoking abstinence (Xu et al., 2010). These studies appear to support the benefit of high cross-domain, general self-expansion. The present study aimed to contribute to this line of research by validating a measure of general self-expansion.

We made minor adaptations to the two scales to generate a measure of general self-expansion. The ISEQ questions are designed to measure the effects of the activity respondents just engaged in (e.g., “How much has doing the previous activity increased your knowledge?”), and we substituted “the activities you did recently” for “the previous activity”. We then asked the respondents to think about their lives over the past three months, so we could measure the self-expanding effects of any activities occurring within this period of time. In the SEQ, the phrase “your partner” was replaced by “the people around you” to measure the self-expansion induced through any relationships. A three-month time limit was also applied, as our focus was on their recent states and the influences of others may change as the respondents encounter new people. These adaptations were approved by the scale developer. We expected that the composite scale consists of two factors measuring the relational and nonrelational self-expansion and it has good reliability and validity.

Two studies were conducted to assess our hypotheses. Study 1 was conducted with university students and exploratory factor analyses were performed to test the structure of the scales. Study 2 aimed to assess the scales by a confirmatory factor analysis and to extend the findings to the population of working adults In both studies, we assessed the convergent validity of the scales against three conceptually related variables and examined the predictive validity of the scales.

Study 1

In Study 1 we tested the psychometric properties of the scales with university students. We measured openness to experience, sensation seeking, and trait epistemic curiosity to test convergent validity, as they reflect one’s disposition to invest in activities that bring novelty for the self and there is evidence for their associations with self-expansion (e.g., Gordon & Luo, 2011; Hughes et al., 2020). We tested predictive validity using self-esteem, self-efficacy, positive affect, and life satisfaction; as reviewed above, self-expansion has shown positive relationships with these outcomes (e.g., Graham, 2008; Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2013). All the measures showed good internal consistency, and their Cronbach’s alpha coefficients appear in Table 3.

Method

Participants

The participants were 335 undergraduate students (76 males, 22.7%), of which 56.4% were students of two universities in a city in Central China, and the remainder were recruited online. Their ages ranged between 18 and 23 (M = 20.12, SD = 1.21) and 3.9% were freshmen, 28.7% sophomore, 51.3% juniors, and 16.1% seniors. Most of the participants (74.6%) were single, 22.7% were dating exclusively, 1.5% were dating casually, and 0.06% were married. They signed up for an online study on “personality and well-being” and received 5 CNY (about 0.8 USD) for completing the survey.

Measures

Self-Expansion Questionnaires

We administered the Chinese translations of the 14-item SEQ (Lewandowski & Aron, 2002) and 5-item ISEQ (Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2013). The participants rated all items on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not very much) to 7 (very much).

Openness to Experience

We used the openness to experience subscale from the Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory Brief Version (CBF-PI-B; Wang et al., 2011). This subscale includes eight items (e.g., “I have a good imagination”). The participants responded on a 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging to 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree).

Sensation Seeking

We used the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS; Hoyle et al., 2002). The Chinese version of this scale has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties (Chen et al., 2013). The eight-item scale includes measures of the four dimensions of experience seeking (“I’m interested in almost everything that is new”), boredom susceptibility (“I get restless if I do the same thing for a long time”), thrill and adventure seeking (“Take adventures always makes me happy”), and disinhibition (“I would do anything as long as it exciting and stimulating”), with each having two items. The respondents rated each item on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).\

Trait Epistemic Curiosity

The Curiosity and Exploration Inventory (CEI-II, Kashdan et al., 2009) includes 10 items to measure individuals’ tendency to seek new information and experiences (e.g., stretching; “I view challenging situations as an opportunity to grow and learn”) and their acceptance of novelty and uncertainty in everyday life (e.g., embracing; “I am the type of person who really enjoys the uncertainty of everyday life”). A previous study of a Chinese version supported a one-factor rather than a two-factor structure (Ye et al., 2015). The participants responded on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Self-Esteem

The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) is a 10-item scale measuring self-worth (e.g., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”). Following previous studies that apply Chinese versions, Item 8 (“I wish I could have more respect for myself”) was deleted to improve internal consistency and structural validity (e.g., Tian, 2006). The participants rated the items along a 4-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly disagree).

Self-Efficacy

We used the General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995), which includes 10 items, to measure a person’s belief in their ability to cope with difficult demands in life (e.g., “I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort”). The Chinese version has shown good psychometric properties (Wang et al., 2001). The participants responded on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly disagree).

Satisfaction with Life

We use the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) to measure how content the participants were with their lives (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”). The Chinese translation has been shown to have adequate psychometric properties (Xing et al., 2002). The participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Positive and Negative Affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) consists of two 10-item subscales to measure positive affect (“excited”) and negative affect (“upset”) over the past week. We used a Chinese version (Huang et al., 2003). The participants rated all items on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Results

We conducted three exploratory factor analyses to examine the factor structure of the ISEQ, SEQ, and the combined scale. We also calculated bivariate correlations to test the validity of the measures.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Table 1 shows that the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy in the three EFAs was sufficient, and that Bartlett’s tests of sphericity were significant (ps < 0.001). As expected, the scree plot and eigenvalue criteria suggested that both the ISEQ and SEQ were unidimensional scales. In terms of the combined scale, the scree plot, eigenvalue criteria (λ1 = 10.37, λ2 = 1.61), and the parallel analysis (λ′1 = 1.44, λ′2 = 1.36) indicated two factors. All of the items adequately loaded on a factor of relational self-expansion and a factor of individual self-expansion, with loadings ranging from 0.53 to 0.88 (see Table 2). Thus, we retained the two factors and tested the two-factor model in the confirmatory factor analysis in Study 2.

Scale Reliability and Inter-Correlations

The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach's α) of the ISEQ and SEQ were 0.88 and 0.95, respectively, and removing any of the items from the scales reduced the levels of reliability. Thus, they demonstrated good internal reliability. We found a significant correlation between individual and relational self-expansion, r = 0.67, p < 0.001. The reliability of the combined scale was excellent, with α = 0.95.

Convergent and Predictive Validity

We examined the bivariate correlations between the self-expansion scores and the other measures (see Table 3). The correlations between self-expansion and openness to experience, sensation seeking, and epistemic curiosity were significant, providing evidence for the convergent validity of the self-expansion scales with our sample of Chinese people. As expected, the self-expansion scores were positively correlated with the predictive measures, including self-esteem, self-efficacy, life satisfaction, and positive affect. No correlation was found between the self-expansion scores and negative affect.

Discussion

The findings supported the high levels of internal consistency and unidimensionality of the SEQ and ISEQ with our sample of university students. When combined, the scales provided a reliable measure of general self-expansion with two factors. The scores of the two scales and the combined scale were also significantly associated with three conceptually related variables, indicating good convergent validity. The patterns of the correlations also supported their predictive validity.

Study 2

In Study 2, we collected data from working adults and conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs). We tested the unidimensionality of the SEQ and ISEQ and compared the two-factor model of the composite self-expansion measure with the one-factor model. We again tested convergent and predictive validity with this sample. We recruited participants from Wen Juan Xing, a leading online survey platform in China, whose subject pool consists of respondents from throughout the country. The platform randomly selected respondents who were working full-time to complete the online survey.

Method

Participants

The participants were 327 Chinese adults (148 males, 45.3%; 178 females, 54.4%; 1 unidentified, 0.3%). Their ages ranged from 22 to 57 (M = 32.18, SD = 5.88). They were all full-time employees of various organizations across mainland China. A majority (73.1%) were married, 5.8% were dating exclusively, 2.1% were dating casually, and 19% were single.

Measures

The measures were identical to those used in Study 1.

Results

We conducted CFAs using structural equation modeling (SEM) in Mplus 7.4. We used common fit indices for SEM, including chi-square, the chi-square over degrees-of-freedom (χ2/df), the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). We used maximum likelihood as the estimation method. Good model fit was assumed as χ2/df < 4, CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95 (values between 0.90 and 0.95 indicate acceptable fit), RMSEA ≤ 0.06 (values between 0.07 and 0.08 are indicative of moderate fit, and those between 0.08 and 0.10 are considered marginal fit), and SRMR ≤ 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

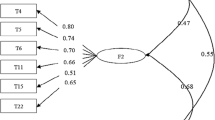

Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA)

We conducted CFAs to evaluate the unidimensional structure of the ISEQ and the SEQ (see Table 4). The scores for the ISEQ showed good or acceptable fit on CFI, TLI, and SRMR, but the RMSEA and χ2/df values did not indicate good fit. However, the SEQ scores suggested good model fit, indicating that the scale is unidimensional. The data for Study 1 showed a two-factor structure for the composite measure of self-expansion, so we tested this model and compared its fit indices to those of a one-factor alternative model (with all items loaded onto one factor). The two-factor model showed acceptable fit indices and provided a significantly better fit than the one-factor model, Δχ2(1) = 139.33, p < 0.001. Thus, as in Study 1, relational and individual self-expansion were independent factors.

Scale Reliability and Inter-Correlations

The ISEQ and SEQ demonstrated good internal consistency, with α = 0.81 and 0.90, respectively. The measure of general self-expansion (combining the two scales) also showed excellent internal consistency, with α = 0.92. The scores for individual and relational self-expansion were positively correlated, with r = 0.64, p < 0.001.

Convergent and Predictive Validity

The bivariate correlations between the self-expansion scores and those of concurrent measures are shown in Table 3. The self-expansion scores were positively associated with those of openness to experience, sensation seeking, and curiosity, with ps < 0.01. As predicted, we found correlations between self-expansion, self-efficacy, self-esteem, life satisfaction, and positive and negative moods.

Discussion

The findings for the non-student sample generally replicated those in Study 1 and provided additional evidence for the reliability and validity of the scales. The unidimensional structure of the SEQ was supported by the EFA in Study 1 and the CFA in this study, with all fit indices suggesting acceptable model fit. In terms of the ISEQ, although the EFA showed a unidimensional structure in the student sample, the CFA in the adult sample provided mixed results. Both the scales indicated good internal consistency and convergent and predictive validity. The composite measure of self-expansion also demonstrated good psychometric properties, and the two-factor structure was once again supported.

General Discussion

Main Findings of the Present Study

The aims of this research were to examine the psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Self-Expansion Questionnaire (SEQ; Lewandowski & Aron, 2002) and the Individual Self-Expansion Questionnaire (ISEQ; Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2013) and to assess whether a composite scale that combined and adapted the two scales could be an acceptable measure of the general self-expansion. The two studies generally support the applicability of these questionnaires to Chinese adult populations (i.e., university students and employees), because they demonstrated good internal reliability and convergent and predictive validity. The composite scale also showed good internal reliability and convergent and predictive validity. Its two-factor structure consisted of the self-expansion gained through interpersonal relationships and through activities conducted alone. The composite scale is appropriate for measuring the levels of perceived self-expansion from both relational and nonrelational sources during a certain period of time.

Comparison with Other Studies

The Chinese version of the SEQ and ISEQ demonstrated adequate psychometric features, particularly the SEQ. Acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.81-0.95) was demonstrated across the studies. Drawing on the self-expansion model (e.g., Aron & Aron, 1986; Aron et al., 2013), we expected openness to experience, sensation seeking, and curiosity to be related to a greater level of perceived self-expansion, as individuals are more likely to include novel content in their self-concepts after they gain more novel experiences. Openness to experience and sensation seeking were positively associated with the preference for self-expansion, a personality trait reflecting a tendency to pursue new experiences and self-growth (Gordon & Luo, 2011; Hughes et al., 2020). The self-expansion scores were positively correlated with openness to experience, sensation seeking, and epistemic curiosity, supporting the convergent validity of the scales.

Self-expansion was positively associated with self-esteem and self-efficacy (rs = 0.25-0.39), which supports the predictive validity of the scales and is in line with research in the U.S. (e.g., Aron et al., 2013; Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2013) and China (e.g., Niu, 2017). The self-expansion model suggests that the motivation for self-expansion is fundamentally instrumental in enhancing the capability to tackle future challenges, individuals thus tend to evaluate themselves more favorably and have more confidence in their abilities when they acquire new self-identities. Self-expansion was associated with greater positive affect (rs = 0.50-0.58) and life satisfaction (rs = 0.36-0.43), consistent with the findings that the subjective feelings accompanying self-expansion are pleasant and that people feel satisfied with the sources of self-expansion such as romantic relationships (e.g., Aron et al., 2000; Graham, 2008) and jobs (McIntyre et al., 2014).

The differences between the results of the two samples represent interesting findings, although we cannot test whether these differences were meaningful because the datasets were collected at different time points. The self-expansion scores of the two groups seemed to differ (student: M = 4.56 and 4.60 vs. employee: M = 5.21 and 5.03). Little research has compared these two groups in terms of self-expansion. One possibility is that the working adults were drawn from the volunteer participant pool of a survey company, they might be curious about research and new knowledge, leading to higher self-expansion.

As Table 3 shows, the self-expansion of university students seemed to be more closely correlated with sensation seeking (0.36 and 0.31) than that of employees (0.19 and 0.26). Research has suggested that sensation seeking declines as people age (Zuckerman et al., 1978), so employees may be less likely to gain self-expanding experience because of the motivation to seek excitement and adventure. Additionally, self-expansion did not correlate with negative affect in the student sample, whereas a negative correlation was found in the employee sample. The relationship between self-expansion and positive affect has been the focus of theoretical and empirical research (e.g., Aron et al., 2000; Graham, 2008), less is known about whether a relatively low level of self-expansion leads to negative affect, although the rapid diminishment of self-concept following the failure of a self-expanding relationship may do so (for example, see the discussion on relationship dissolution in Aron et al., 2013). Other research shows that a lower degree of self-expansion increases the likelihood of infidelity in a relationship (Lewandowski & Ackerman, 2006), but other outcomes could be investigated to provide further insights into the impact of self-expansion on negative affect.

Implications and Explanation of Findings

As our review attests, research into self-expansion in Chinese people is extremely limited and validated measures are clearly required. Our findings suggest that the Chinese SEQ and ISEQ have adequate psychometric features and can thus be useful in future research. Researchers could change the source of self-expansion and apply the scales to different research areas, including different types of interpersonal relationships, intergroup relations, and relationships with nonhuman objects such as technology and brands. Future studies could enhance the theory of self-expansion by providing evidence from a collectivist culture.

Another implication of the present study was the validation of a measure of general self-expansion. By combining and slightly modifying the two scales, the composite scale measured self-expanding experiences recently acquired from both relational and nonrelational sources. The findings suggested that the composite scale had good internal consistency and that the items reflected two factors, which had a large positive correlation, r = 0.69 (Study 1) and 0.64 (Study 2). Relational and nonrelational forms of self-expansion have been mostly investigated separately, with the former linked to social relationships and the latter to individual performance (see Mattingly & Lewandowski, 2014a, for a review). As mentioned, some studies have suggested that wellbeing outcomes may be affected by a general level of self-expansion, regardless of the sources. For example, the total amount of self-expanding experiences in various life domains was found to be related to smoking abstinence (Xu et al., 2010), suggesting the value of studying the general self-expansion. Self-expansion often leads to positive moods and positive self-evaluation, which can influence behaviors in different life domains. Thus, our composite scale could be applied to future research in this area.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Conclusions

Although our work contributes to self-expansion research in the Chinese context, it has three main limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, our two studies validated the self-expansion scales for university students and employees, which are adult populations. Our findings suggest possible age differences in the association between self-expansion and personality traits (e.g., sensation seeking) and in specific outcomes of self-expansion (e.g., negative affect). Comparing the self-expansion of different age groups would be of benefit, particularly regarding the potential differences in health and well-being outcomes. Second, we did not evaluate the test–retest reliability of the scales, and thus future research could assess the scales’ temporal stability. Third, we measured self-esteem and self-efficacy but no other facets of self-concept, such as its clarity, size, or diversity. Whether self-expansion relates to self-concept similarly across cultures, considering cultural differences in self-construals, remains an open question. Future research could examine more facets of self-concept with subjects from individualist and collectivist cultures.

The view of self-expansion as a basic human motivation requires more cross-cultural research. As collectivist cultures encourage interdependent self-construals, whereas individualist cultures promote independent self-construals (Markus and Kitayama, 1991), interesting commonalities and differences in the motivations and consequences of self-expansion may be revealed through cultural comparisons. The present study has suggested that the Chinese SEQ, ISEQ, and the composite scale of general self-expansion are suitable for future studies of Chinese people, which may shed light on the self-expansion theory.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable

References

Aron, A., & Aron, E. (1986). Love and the expansion of the self: Understanding attraction and satisfaction. Hemisphere.

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

Aron, A., Norman, C. C., Aron, E. N., McKenna, C., & Heyman, R. E. (2000). Couples’ shared participation in novel and arousing activities and experienced relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.273

Aron, A., Paris, M., & Aron, E. N. (1995). Falling in love: Prospective studies of self-concept change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(6), 1102–1112. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.6.1102

Aron, A., Lewandowski, G. W., Jr., Mashek, D., & Aron, E. N. (2013). The self-expansion model of motivation and cognition in close relationships. In J. A. Simpson & L. Campbell (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of close relationships (p. 90–115). Oxford University Press.

Bi, C., Oyserman, D., Lin, Y., Zhang, J., Chu, B., & Yang, H. (2020). Left behind, not alone: Feeling, function and neurophysiological markers of self-expansion among left-behind children and not left-behind peers. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(4), 467–478. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa062

Chen, X., Li, F., Nydegger, L., Gong, J., Ren, Y., Dinaj-Koci, V., Sun, H., & Stanton, B. (2013). Brief Sensation Seeking Scale for Chinese—Cultural adaptation and psychometric assessment. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(5), 604–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.007

Cui, J. H. (2013). Ziwo kuozhang yu tiaojie dingxiang dui qinmi guanxi yingxiang de yanjiu [The study of the relationship between self-expansion and regulatory focus in close relationships] [Master’s thesis, Southwest University]. CNKI China Master’s Theses Full-text Database.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Fisher, H. E., Xu, X., Aron, A., & Brown, L. L. (2016). Intense, passionate, romantic love: a natural addiction? How the fields that investigate romance and substance abuse can inform each other. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 687. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00687

Fivecoat, H. C., Tomlinson, J. M., Aron, A., & Caprariello, P. A. (2015). Partner support for individual self-expansion opportunities: Effects on relationship satisfaction in long-term couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 32(3), 368–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514533767

Gordon, C. L., & Luo, S. (2011). The Personal Expansion Questionnaire: Measuring one’s tendency to expand through novelty and augmentation. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(2), 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.015

Graham, J. M. (2008). Self-expansion and flow in couples’ momentary experiences: An experience sampling study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 679–694. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.679

Guo, J. C. (2011). Ziwo jiegou de qidong dui ziwo kuozhang dongji shuiping de yingxiang shiyan yanjiu [The effects of self-construal priming on self-expansion moviation] [Master’s thesis, Southwest University]. CNKI China Master’s Theses Full-text Database.

Hambleton, R. K., Merenda, P. F., & Spielberger, C. D. (2004). Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment. Erlbaum.

Hoyle, R. H., Stephenson, M. T., Palmgreen, P., Pugzles Lorch, E., & Donohew, R. L. (2002). Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(3), 401–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00032-0

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang, L., Yang, T. Z., & Ji, Z. M. (2003). Zhengxing fuxing qingxu liangbiao de zhongguo renqun shiyongxing yanjiu [Applicability of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale in Chinese]. Zhongguo Xinli Weisheng Zazhi, 17(1), 54–56.

Hughes, E. K., Slotter, E. B., & Lewandowski, G. W., Jr. (2020). Expanding who I am: Validating the Self-Expansion Preference Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 102(6), 792–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2019.1641109

Jia, F. X. (2012). Ziwo kuozhang yu shijian weidu shang de guanxi manyidu pingjia de guanxi yanjiu [The study of the relationship between self-expansion and temporal relation-appraisal] [Master’s thesis, Southwest University]. CNKI China Master’s Theses Full-text Database.

Jia, F. X., & Shi, W. (2012). Ziwo kuozhang moxing de yanjiu shuping [A Review of Self-expansion Model]. Xinli Kexue Jinzhan, 20(1), 137–148.

Kashdan, T. B., Gallagher, M. W., Silvia, P. J., Winterstein, B. P., Breen, W. E., Terhar, D., & Steger, M. F. (2009). The Curiosity and Exploration Inventory-II: Development, factor structure, and psychometrics. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(6), 987–998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.04.011

Lai, X. L., Liu, X. L., & Li, L. (2018). Qinmi guanxi zhong de ziwo kuozhang [Self-expansion in close relationships]. Xinli Kexue Jinzhan, 26(12), 2170–2179.

Lewandowski, G. W., Jr., & Aron, A. (2002). The self-expansion scale: Construction and validation. Paper presented at the Third Annual Meeting of the Society of Personality and Social Psychology, Savannah, GA.

Lewandowski, G. W., Jr., & Ackerman, R. A. (2006). Something’s missing: Need fulfillment and self-expansion as predictors of susceptibility to infidelity. The Journal of Social Psychology, 146(4), 389–403. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.146.4.389-403

Liu, Q., Huang, J., & Zhou, Z. (2020). Self-expansion via smartphone and smartphone addiction tendency among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Children and Youth Services Review, 119(C). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105590

Mao, J., Chiu, C. Y., Owens, B. P., Brown, J. A., & Liao, J. (2019). Growing followers: Exploring the effects of leader humility on follower self-expansion, self-efficacy, and performance. Journal of Management Studies, 56(2), 343–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12395

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

Mattingly, B. A., & Lewandowski, G. W., Jr. (2013). The power of one: Benefits of individual self-expansion. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2012.746999

Mattingly, B. A., & Lewandowski, G. W., Jr. (2014a). Broadening horizons: Self-expansion in relational and non-relational contexts. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12080

Mattingly, B. A., & Lewandowski, G. W. (2014b). Expanding the Self Brick by Brick: Nonrelational Self-Expansion and Self-Concept Size. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(4), 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550613503886

McIntyre, K. P., Mattingly, B. A., Lewandowski, G. W., Jr., & Simpson, A. (2014). Workplace self-expansion: Implications for job satisfaction, commitment, self-concept clarity, and self-esteem among the employed and unemployed. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 36(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2013.856788

Niu, G. F. (2017). Wangluo ziwo kuozhan de gainian jiegou, celiang jiqi shizheng yanjiu [The conceptual structure and measurement of online self-expansion, and its empirical studies] [Doctoral dissertation, Central China Normal University]. CNKI China Doctoral Dissertations Full-text Database.

Pu, K. H. (2013). Daxuesheng ziwo kuozhan, ziwo gainian yu aiqing jidu de xianzhuang jiqi guanxi yanjiu [A study of the relationships between self-expansion, self-concept, and romantic jealousy among college students] [Master’s thesis, Yunnan Normal University]. CNKI China Master’s Theses Full-text Database.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Optimistic self-beliefs as a resource factor in coping with stress. In S. E. Hobfoll & M. W. deVries (Eds.), NATO ASI series. Extreme stress and communities: Impact and intervention (p. 159–177). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-8486-9_7

Shedlosky-Shoemaker, R., Costabile, K. A., & Arkin, R. M. (2014). Self-expansion through fictional characters. Self and Identity, 13(5), 556–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2014.882269

Tian, L. M. (2006). Rosenberg (1965) zizun liangbiao zhongwenban de meizhongbuzu [Shortcoming and merits of Chinese version of Rosenberg (1965) Self-Esteem Scale]. Xinlixue Tanxin, 26(2), 88–91.

Wang, M. C., Dai, X. Y., & Yao, S. Q. (2011). Zhongguo dawu renge wenjuan de chubu bianzhi III: Jianshiban de zhiding ji xinxiaodu jianyan [Development of the Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory (CBF-PI) III: Psychometric Properties of CBF-PI Brief Version]. Zhongguo Linchuang Xinlixue Zazhi, 19(4), 454–457.

Wang, C. K., Hu, Z. F., & Liu, Y. (2001). Yiban ziwo xiaonenggan liangbiao de xindu he xiaodu yanjiu [Evidences for Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of General Self Efficacy Scale]. Yingyong Xinlixue, 7(1), 37–40.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Xing, Z. J., Wang, X. Z., Jiao, L. P., Zhou, T. N., Zhang, R. K., Yu, X. Y., Li, Y. Y., Yu, L. H., & Ning, F. H. (2002). Jizhong changyong zichen zhuguan xingfugan liangbiao zai woguo chengshi jumin zhong de shiyong baogao [Report on several common self-reported subjective well-being scales used to citizens in China]. Jiankang Xinlixue Zazhi, 10(5), 325–326.

Xu, X., Floyd, A. H., Westmaas, J. L., & Aron, A. (2010). Self-expansion and smoking abstinence. Addictive Behaviors, 35(4), 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.019

Ye, S., Ng, T. K., Yim, K. H., & Wang, J. (2015). Validation of the Curiosity and Exploration Inventory–II (CEI–II) among Chinese university students in Hong Kong. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97(4), 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1013546

Zuckerman, M., Eysenck, S. B., & Eysenck, H. J. (1978). Sensation seeking in England and America: Cross-cultural, age, and sex comparisons. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46(1), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.46.1.139

Funding

This work was supported by the research fund from MWOP Reserve at the Department of Applied Psychology of Lingnan University (#770056).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Lingnan University. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Peng, M. & Lewandowski, G.W. Psychometric evaluation of a Chinese translation of the relational and individual self-expansion scales. Curr Psychol 42, 12671–12681 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02585-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02585-8