Abstract

Though not having children is no longer as unusual as it once was, voluntary childlessness is still a controversial choice that might generate moral outrage against people who choose not to have children. The current study explored the associated factors related to the attitudes towards voluntary childlessness in a sample of 418 adults aged 18 to 82 (M = 28.94, SD = 12.63, 76.1% females). Specifically, we investigated the links between participants’ attitudes toward benevolent and hostile sexism, religiosity, and a series of demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, education, relationship status, and parental status). Based on previous related literature, we hypothesized that sexism would mediate the relationship between religiosity and voluntary childlessness. Results suggested that older and married participants with children had more negative attitudes related to voluntary childlessness. Additionally, overall sexism and its two dimensions (hostile and benevolent sexism) partially mediated the relationship between religiosity and attitudes towards voluntary childlessness. The practical implications of these results are discussed in light of Romania’s cultural and socio-economic context, a post-communist country and the most religious state in Europe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

How many children do you want to have? One of the main challenges in the current modern society is the choice concerning parenthood. Nowadays, infertile couples can choose between various ways of assisted reproductive techniques (e.g., in vitro fertilization), adoption, or surrogate mothers, though the attitudes towards these options broadly vary across cultures (Bello et al., 2014; Grunberg et al., 2020; Igreja & Ricou, 2019; Maftei & Holman, 2020), and the most preferred choice seems to be the biological link, i.e., biological parenthood (Bell, 2019). However, couples worldwide seem to increasingly consider voluntary childlessness (i.e., the choice of fertile couples not to have any children) as an alternative to parenthood (Ahmadi et al., 2019). Though having children remains a universal desire (Purewal & Van den Akker, 2007), not having children is no longer as unusual as it once was. According to Livingston and Cohn (2010), one-in-ten American women in the 1970s were childless. By 2005, these numbers have doubled: one in five women up to the age of 40 had never had a child, and the declining birthrate is not limited to the United States, but it is instead a worldwide phenomenon (CBS/AP, 2014; Frejka & Calot, 2001; González & Jurado-Guerrero, 2006). Although these numbers have changed since 2005, they never came close to those of the 1970s. Moreover, according to more recent data, there seems to be an increase in childlessness within European societies (Mills et al., 2011; Sobotka, 2009; Tanturri & Mencarini, 2008).

In light of a series of political movements from the 1960s and 1970 (e.g., second-wave feminism), voluntary childlessness received cultural support, at least in Western countries and the United States (Park, 2002). However, this was not the case for Romania, now a post-communist country previously forced towards a rigid, mandatory pronatalist public policy. One of the most persistent collective memories related to the communist period in Romania is the 1966 anti-abortion decree that imposed a pronatalist regime encouraging a high number of children to reach a high natality rate that would correspond to the assumed economic progress of the population (Berelson, 1979). Women were not given a choice, and, more importantly, they were severely punished, by law, for any attempt to terminate a pregnancy, as they were expected to be “mothers of the nation” (Marinescu, 2020). As a result of the restrictive reproductive health policies, in the 1980s, Romania had the highest mortality rate in Europe due to unsafe, illegal abortions (Hord et al., 1991). Thus, voluntary childlessness was only an option for Romanian women in the post-communist era (i.e., since 1990).

In addition to the individual and demographical factors that may lead to higher acceptance of voluntary childlessness, the social acceptance of childlessness seems to differ depending on the socio-cultural context (Whitehead, 2006). For example, in a comprehensive report related to childlessness in Europe, Mills et al. (2015) provided several theoretical explanations related to the socio-cultural factors that might explain contemporary fertility behavior and, generally, people’s choice to have or not to have children. Within the cultural perspective, the authors detail, for example, van de Kaa’s (1987) Post-Material Values Theory paradigm, which suggested that modern systems usually favor self-realization and individual options, rather than traditional systems that maximized the well-being of the family. Thus, childlessness might be a result of contemporary partnerships, “characterized by egalitarianism and individualism, with parenthood no longer an intrinsic aspect of such relationships” (Mills et al., 2015, p. 15).

In Europe, there are significant related variations, according to Merz and Liefbroer (2012). The highest approval rates related to childlessness were found in northern and western European countries, while the lowest approval rates were found in formerly communist eastern European countries. Also, according to Testa (2012), the two-child family seems to remain the most preferred family version for Europeans (around 50%), Romanians included (around 60%). As Mills et al. (2015) suggested, in Eastern Europe (thus, in Romania as well), “childless men could be considered cultural ‘forerunners’ in a context characterized by relatively high values of family life and children, low levels of gender equality within the family and also by inadequate opportunities for combining work and family”; (...) “voluntary childlessness could spread in a different way across social classes: it might become more and more common among both “power women” and “unsuccessful men” (p. 35).

Cultural norms and values encourage reproduction, the general perception of childfree women being mostly negative (Mueller & Yoder, 1997; Park, 2002). People generally consider that one cannot be entirely satisfied with their life without any children (Ashburn-Nardo, 2017; Vinson et al., 2010). Adults who choose not to have children are generally stigmatized, considered abnormal, selfish, or lacking a sense of responsibility (Dever & Saugeres, 2004; Gillespie, 2000; Letherby, 2002; Park, 2002). Based on one’s parental status, women without children are usually perceived more negatively than those having children (Bays, 2017; Kopper & Smith, 2001), triggering envy and disgust (Bays, 2017). Koropeckyj-Cox and her collaborators (2015), for example, suggested that, generally, parents were perceived as more warm than non-parents, but with less positive marital relationships; meanwhile, voluntary childless married women were perceived as more emotionally troubled and less warm.

Voluntary childlessness also seems to be considered a controversial choice that might generate moral outrage (i.e., anger, disapproval, and disgust) against people who choose not to have children, therefore, considered as violating the social roles and stereotypic expectations that consider parenthood as a moral imperative (Ashburn-Nardo, 2017). Ashburn-Nardo’s findings represent the first known empirical evidence that outlines parenthood as a moral imperative and highlights the potential consequences that voluntary child-free people experience. Given these findings and their significant implications at both social and individual levels, as well as the scarce related data from Romania, we considered it important to explore the associated factors related to the attitudes toward voluntary childlessness considering the particularities of this post-communist cultural European space.

Religiosity and Attitudes toward Voluntary Childlessness

Religiosity was extensively documented and identified as a significant factor related to fertility behavior worldwide (e.g., Götmark & Andersson, 2020; Peri-Rotem, 2016; Pinter et al., 2016). For example, religious individuals are less likely to consider surrogacy or other assisted reproductive technologies such as in-vitro fertilization (Demeny, 2017; Maftei & Holman, 2020). On the other hand, religious people are more likely to support and encourage high fertility rates (thus, more children) since most of them elaborated moral codes guiding individuals’ reproductive behavior, i.e., procreation and gender roles (McQuillan, 2004; Moulasha & Rao, 1999). Hayford and Morgan (2008) also suggested that those who consider religion an essential factor in their lives seem to have more traditional gender and family attitudes, though these links are also subject to cultural norms and ideologies.

The research exploring the specific link between religiosity and voluntary childlessness generally suggested that the more negative attitudes toward voluntary childlessness are higher among individuals with conservative religious beliefs (Koropeckyj-Cox & Pendell, 2007; Merz & Liefbroer, 2012; Noordhuizen et al., 2010). Furthermore, less religious individuals seem to be more likely to be childfree (Avison & Furnham, 2015) since religiosity is often associated with parenthood and the wanted number of children (Abma & Martinez, 2006). Earlier studies also suggested that voluntary childlessness was associated with less traditionalism and religiosity (Heaton et al., 1992, 1999; Tanturri & Mencarini, 2008).

According to Pew Research Centre (2018), Romania is the most religious country in Europe (> 85% Orthodox). Both the Orthodox and the Catholic Churches in Romania declared their opposition to assisted reproductive technologies, contrary to their support for adoption. In any case, fertility is encouraged, as in many other religious communities around the world. Husnu (2016), for example, suggested the critical role played by religiosity and ambivalent sexism in predicting undergraduate students’ attitudes towards voluntary childlessness.

Ambivalent Sexism and Voluntary Childlessness

Sexism comprises gender-based discrimination, highly related to gender roles and stereotypes. According to Bahtiyar-Saygan and Sakallı-Uğurlu (2019), ambivalent sexism, a theory developed by Glick and Fiske (1996), “explores both male dominance and intimate interdependence by covering issues of patriarchy, gender role differentiation (different social roles and occupations), and heterosexual intimacy” (p. 7). In many cultures, women’s roles and identities are shaped through motherhood (Holton et al., 2009; Sakallı-Uğurlu et al., 2018), and Romania is no exception. Hostile sexism highlights the punitive attitudes towards women who violate traditional norms, whereas benevolent sexism refers to the admiration and praise of women who conform to traditional gender roles and norms, including motherhood.

Both Hostile and Benevolent sexism enforce traditional gender roles and underline the inequalities between men and women. Therefore, ambivalent sexism seems to be a significantly associated factor related to the attitudes towards voluntary childlessness: since women “should” be mothers according to the sexist stereotypes dominated by paternalism, thus, rejecting motherhood equals violating their gender prescriptions (Merz & Liefbroer, 2012; Tanturri & Mencarini, 2008). Consequently, it is reasonable to consider that higher levels of benevolent sexism might be associated with higher levels of stigma concerning women who choose not to have children.

Since “the nonconformity of women and men to have a child in marriage may challenge pronatalist and sexist ideologies” (...), “it is possible to deduce that women are generally under the social pressure of having a child, especially in patriarchal cultures” (Bahtiyar-Saygan & Sakallı-Uğurlu, 2019, p.8). On the other hand, men who choose voluntary childlessness are not as harshly judged, as women are: “A man who displays no desire to become a father could be considered as “sowing his wild oats” or unwilling to “settle down”; any number of reasons could be made for his choice, but most likely, as a man, he would not have to defend his choice to refuse fatherhood” (Vidad, 2009, p. 3). However, when Rijken and Merz (2014) explored the differences in norms related to voluntary childlessness for men and women, their results suggested higher disapproval rates for men who chose voluntary childlessness. Moreover, the authors suggested that “higher levels of gender equality were associated with larger double standards favoring women” (p. 470). Though their results were observed in a large Australian population, which may significantly differ from European societies such as Eastern Europe, their contrasting findings ask for further related research.

Religiosity and Sexism: The Romanian Case

An extensive number of studies (e.g., Burn & Busso, 2005; Diehl et al. 2009) suggested that traditional religions, i.e., Christianity and Islam are more likely to promote traditional gender role attitudes (including protective paternalism). However, other researchers pointed out that, regardless of one’s religion and its conservative or liberal overall approach, religiosity is highly related to family values and traditions (e.g., Myers, 2004). For example, individual autonomy seemed less important than obedience toward family and traditional family models for individuals affiliated with various Christian churches (Mahoney, 2005). In other studies, Catholic religiosity predicted more benevolent sexist attitudes (Glick et al., 2002), while Islamic religiosity positively predicted honor beliefs that prioritize family reputation through men’s control over women and women’s religious piety and sexual modesty (Glick et al., 2016).

Generally, previous research exploring the specific link between hostile sexism, benevolent sexism, and religiosity indicated a positive, significant association between these dimensions (Mikołajczak & Pietrzak, 2014). For example, Taşdemir and Sakallı-Uğurlu (2010) suggested that Muslim religiosity was significantly associated with hostile sexism. However, similar investigations in Christian samples suggested contrasting findings, with religiosity being significantly linked to benevolent sexism and not hostile sexism. Nevertheless, as Glick et al. (2002) highlighted, the relationship patterns between ambivalent sexism and religiosity are subject to fluctuations due to the ideologies promoted by other religions.

To our knowledge, there is a scientific gap in exploring the specific link between sexism and religiosity in Romanian samples (which is 86.6% Orthodox, according to the Commssion, 2019), and we aimed to address this issue in the present research, within the voluntary childless framework. However, previous research suggested that gender inequality based on hostile and benevolent justifications in Romania has one of the lowest rates in Europe (Napier et al., 2010). Additionally, similar to voluntary childlessness, the current Romanian religious dynamic is a tributary to the religious restrictions and repressive decisions imposed by the communist regime until 1989. Data from the European Values Survey showed that the Romanian church’s trust level was around 86% in 2008 (Müller, 2011). More importantly, the Barometer for Public Opinion (Bădescu et al., 2007) indicated that 83% of Romanian adults considered family and children as the most critical aspect of their life, followed by religion.

Demographic Influences

Among the various factors underlying the choice of not having children and those related to the perception of child-free individuals, demographical correlates had also been underlined by previous research. For example, childlessness seems more common among highly educated people (Abma & Martinez, 2006; Livingston & Cohn, 2010), who have higher incomes, and usually live in urban settings (DeOllos & Kapinus, 2002). Therefore, these factors might also contribute to the understanding of people’s different views related to childlessness. Previous research suggested that younger individuals (Bahtiyar-Saygan and Sakallı-Uğurlu, 2019; Merz & Liefbroer, 2012), with higher educational levels and without children (Koropeckyj-Cox & Pendell, 2007) seem to have more positive attitudes towards voluntary childlessness. Other studies suggested that women who choose childlessness are more likely to be non-religious, less traditional, and to have higher gender equity within their relationships (Hakim, 2005; Tanturri & Mencarini, 2008).

Regarding gender, voluntary childlessness seems generally higher among men than among women across all countries (Hakim, 2005), though further investigations are needed for a more precise and comprehensive view on this matter. However, in several cultural contexts, voluntary childlessness among men was significantly linked to poor education and health and lower social status, opposed to the links related to women who voluntarily chose to remain childless (Barthold et al., 2012; Tanturri, 2010; Waren & Pals, 2013).

Motherhood costs may be highly challenging in career choice and general economic and social costs (Crittenden, 2001). In addition, studies have previously highlighted the parenthood-related inequalities between men and women, e.g., disproportionate responsibility for children’s care and housework (Lachance-Grzela & Bouchard, 2010). Moreover, a high number of studies documented workplace discrimination against women with children, especially towards those who become mothers at younger ages (Correll et al., 2007; Mills et al., 2011), generating a potentially more positive view on voluntary childlessness among women, compared to men (Koropeckyj-Cox & Pendell, 2007). Furthermore, the transition to parenthood may be challenging for both women and men (e.g., it might generate depression and lower levels of emotional well-being), especially in the case of single parents or unplanned pregnancies (e.g., Lawrence et al., 2008; Mitnick et al., 2009; Mollen, 2013).

The Present Study

Our study explored a series of potential factors related to the attitudes towards voluntary childlessness among Romanian adults. Considering the previous related literature (e.g., Bahtiyar-Saygan & Sakallı-Uğurlu, 2019; DeOllos & Kapinus, 2002; Merz & Liefbroer, 2012; Mills et al., 2015), we investigated benevolent sexism, hostile sexism, religiosity, and a series of demographic variables (i.e., age, education, parental status – already having a child or not, and relationship status), and their relationship with participants’ attitudes toward voluntary childlessness. Our primary hypothesis was that sexism would mediate the relationship between religiosity and attitudes towards voluntary childlessness. We also hypothesized that older male participants with children would have more negative attitudes towards voluntary childlessness.

Research Procedure

We used a cross-sectional design to test our hypothesis. The study was designed and ran following the 2013 Helsinki declaration research guidelines and the ethical requirements specific to the faculty where the authors are affiliated. We collected our data using a web-based survey between October and December 2020. Before beginning the study, the survey was piloted with a small sample of young adults in September 2020. Participation was voluntary. All participants were informed that there were no right and wrong answers, that their answers were anonymous and confidential, and that they could retire from de study at any time. The time needed to answer all questions was around 20 min.

Participants

Our convenient sample consisted of 418 participants, aged 18 to 82 (M = 28.94, SD = 12.63). Most of our participants were females (76.1%), and most had no children (71.3%). Table 1 offers a detailed description of our sample’s characteristics (i.e., age, gender, number of children, education, and relationship status). The only inclusion criterion was related to participants’ age (>18 years old).

Research Materials

We used The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS-15; Huber, 2003) to measure participants’ “centrality, importance or salience of religious meanings in personality”. Participants answered to the 15 items on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Example items include “How often do you think about religious issues?” and “How often do you pray?”. Higher scores indicated higher religiosity levels. Cronbach’s alpha indicated excellent reliability of the scale (α = .95).

We further used The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI), developed by Glick and Fiske (1996). The scale measures overall sexism and two separate subscales, namely hostile Sexism and benevolent Sexism. Participants answered 22 items on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). Example items from the Hostile Sexism subscale included “Most women interpret innocent remarks or acts as being sexist” and “There are actually very few women who get a kick out of teasing men by seeming sexually available and then refusing male advances”. The Benevolent Sexism subscale included items such as “No matter how accomplished be is, a man is not truly complete as a person unless he has the love of a woman” and “People are often truly happy in life without being romantically involved with a member of the other sex”. Cronbach’s alpha indicated good reliability values of the scale (α = .771) and its subscales. Higher scores indicated higher sexism levels.

We further used the Attitudes Toward Voluntary Childlessness Scale, developed by Bahar Bahtiyar-Saygan and Nuray Sakallı- Uğurlu (2019). The scale measures the overall attitude towards voluntary childlessness and also comprises three different dimensions: Negative biases against childfree people (example item: “Those who don’t want to have children are the ones who don’t like children”), Necessity of children in being a family and having a happy/meaningful life (example item: “Being a parent is a feeling that everyone should experience when the times comes”) and Supporting individuals’ choice to be childless (reversed items such as “I support a woman’s decision not to have children”). Participants answered 24 items on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). Cronbach’s alpha indicated very good reliability of the overall scale (α = .88). The higher the score, the more negative participants’ attitudes towards voluntary childlessness.

Finally, a demographic scale assessed participants’ age, gender, relationship status, and the number of children. All instruments were pretested in a sample of 34 participants (M = 31.25, SD = 1.25, 45% males), and no related issues were reported.

Results

We used the SPSS (v.24.) and PROCESS (Hayes, 2013) programs to analyze our data. First, we analyzed the relationships between participants’ demographical characteristics, i.e., age, gender, relationship status, the number of children. Male participants is our sample were older (M = 33.18; SD = 15.71) than females (M = 27.61; SD = 11.20), t(132) = 3.29, p < .01, while the latter had fewer children (M = .38; SD = .74) than their male counterparts (M = .68; SD = .89), t(145) = 3.03, p < .01. Gender was also associated to relationship status, χ2 = 7.80, p < .05, “in a stable relationship” being the most frequent category among females (37.1%), while being single was the most frequent in our male group (45%). ANOVA comparisons with Games-Howell corrections indicated that married participants were older (M = 43.52; SD = 11.87) than single participants (M = 23.74; SD = 8.29) and than participants in a stable relationship (M = 22.75; SD = 5.79), both ps < .01. Older participants had more children than the younger ones (r = .76, p < .01). Married participants also had more children (M = 1.44; SD = .77) than those who are single (M = .03; SD = .17) or in a stable relationship (M = .12; SD = .44), both ps < .01.Second,we explored the associations between participants’ demographical characteristicsand their attitude towards voluntary childlessness. As the demographical characteristics emerged as related, the relationship between each of them and the attitude towards voluntary childlessness was analyzed while controlling the others (relationship status was dichotomized when controlling for its effects on the associations between the other three demographic variables and participants’ attitudes). Results of the partial correlation analysis (controlling for gender, number of children and relationship status differences) suggested a significant association with age (r = .12, p < .05), i.e., older participants had a more negative perception of voluntary childlessness. Analyses of covariance with Games-Howell corrections while controlling for the effects of the other demographics indicated no significant differences in terms of participants’ gender (F(1, 413) = .17, p = .68) or relationship status (F(2, 412) = .34, p = .71).. Finally, the number of children also generated significant differences among participants (F(2,412) = 4.45, p < .05) even when controlling for the other demographics. Participants with no children (M = 52.10, SD = 16.52) had significantly more positive attitudes towards voluntary childlessness, compared to the other participants, i.e., people with one child (M = 64.21, SD = 14.44), or two or more children (M = 66.83, SD = 15.31).

We then explored the correlations between participants’ scores on sexism (overall sexism, hostile and benevolent sexism), religiosity, and their attitude towards voluntary childlessness (overall attitude, as well as the three subfactors comprised in the Attitudes Toward Voluntary Childlessness Scale) (see Table 2). Our results suggested significant associations between all the main variables (religiosity, sexism, and attitude towards voluntary childlessness), and the underlying subfactors (i.e., Negative bias, Necessity of children, and Supporting childlessness, Hostile sexism, and Benevolent sexism = subscales of sexism).

We further explored the mediating role of sexism (overall Sexism, followed by hostile sexism, and benevolent Sexism) on the relationship between religiosity and participants’ overall attitude towards voluntary childlessness in PROCESS 3.5 (Hayes, 2013). PROCESS uses a regression-based bootstrapping approach to examine mediation and moderation effects within various types of predefined conceptual models that specify the nature of the relationships between the variables analyzed (Hayes, 2013). The statistical significance and the parameters of the effects in the model under scrutiny are computed in each of a large number of samples drawn from the original one, generating the means and also the bootstrap-based confidence intervals of all these estimates. This allows for more accurate tests of indirect effects than other, more traditional, methods of investigating mediation (Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Hayes & Scharkow, 2013). Statistically significant mediation effects are indicated by confidence intervals of the indirect relationships that do not include zero. Our theoretical hypothesis models were tested by estimating the 95% confidence interval (CI) for mediation effects with 5000 resampled samples.

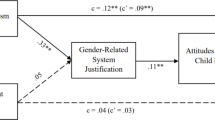

We controlled the effects of gender, age, relationship status, and the number of children, by introducing them as covariates in the mediation analyses. Results (see Fig. 1) suggested that religiosity significantly predicted sexism, b = .009, p < .001, 95% CI [.006–.013], and participants’ overall attitude towards voluntary childlessness was significantly predicted by sexism, b = 12.21, p < .001, 95% CI [9.46–14.97] and religiosity, b = .28, p < .001, 95% CI [.18–.39]. The indirect effect of religiosity on the attitude towards voluntary childlessness was partially mediated by sexism, 95% CI [.07–.16], and the effect size of this mediation was PM = .28.

In order to deepen our results, we further repeated the analysis, testing the mediating roles of the two sexism dimensions, namely hostile Sexism and benevolent Sexism, while controlling for the demographic variables. For the hostile sexism dimension, results (see Fig. 2) suggested that religiosity significantly predicted hostile sexism, b = .005, p = .01, 95% CI [.0016–.008], and participants’ overall attitude towards voluntary childlessness was significantly predicted by hostile sexism, b = 7.17, p < .001, 95% CI [4.79–9.54] and religiosity, b = .36, p < .001, 95% CI [.26–.45]. The indirect effect of religiosity on the attitude towards voluntary childlessness was partially mediated by hostile sexism, 95% CI [.006–.072], and the effect size of this mediation was PM = .009.

For the benevolent sexism dimension, results (see Fig. 3) suggested that religiosity significantly predicted hostile sexism, b = .015, p < .001, 95% CI [.011–.018], and participants’ overall attitude towards voluntary childlessness was significantly predicted by benevolent sexism, b = 11.41, p < .001, 95% CI [8.91–13.91] and religiosity, b = .22, p < .001, 95% CI [.12–.32]. The indirect effect of religiosity on the attitude towards voluntary childlessness was partially mediated by benevolent sexism, 95% CI [.12–.22], PM = .49.

Power Analyses

Firstly, we examined the power of our study to detect, through analyses of covariance, the effects of each of the demographic variables on participants’ attitude towards voluntary childlessness when controlling for the other demographics. To this aim, we performed a sensitivity analysis (Faul et al., 2007) in GPower 3.1 in order to find the minimum size of this type of effect that our sample size can detect as significant. With an alpha = .05 and power = 0.80, the minimum size of an effect of an independent variable with three groups (such as relationship status or number of children) while controlling for three other variables that would be detectable with our sample of 418 participants is f = .15. The size of the significant effect of the number of children is also f = .15, equal to this minimal detectable effect size, which suggests the reliability of this finding. Yet, our study was underpowered to find a weaker statistically significant effect, which implies that the differences between the groups varying in gender and relationship status, which our results indicated as non-significant, may be in fact statistically significant but too small to be discovered within our small sample.

Secondly, we used simulation analysis to calculate the statistical power for our mediation models focusing on the second model, which had the smallest effect size (i.e., PM = .009). We took into account the small size (i.e., β = .12, see Fig. 2) of the first path in this model, between the predictor (i.e., religiosity) and the mediator (i.e., hostile sexism), and the small-to-medium size (β = .25) of the second path, between the mediator and the dependent variable (i.e., attitude towards voluntary childlessness). We then identified the minimum sample size needed for .8 power to detect through the percentile bootstrap test of mediation implemented by PROCESS 3.5, at .05 significance level, a real mediation effect of this size (corresponding to the magnitude of the relationships between the variables in our model). According to the simulation results reported by Fritz and MacKinnon (2007), the minimum sample size needed to this aim is 411. Our sample size (i.e., 418 participants) is above this threshold, which suggests that our study was adequately powered to find even this small indirect effect and, therefore, in the other two hypothesized models as well.

Discussion

Our study aimed to explore the mediating roles of sexism and its dimensions – namely hostile and benevolent sexism, in a sample of Romanian adults. We also investigated the associated demographical factors of the attitudes towards voluntary childlessness, namely age, gender, relationship status, and the number of children. Our primary hypotheses were confirmed: older participants with children, had the most negative attitudes towards voluntary childlessness. These results align with previous studies that suggested that the higher the age, the higher the negative attitudes towards people who decide not to have any children (Bahtiyar-Saygan and Sakallı-Uğurlu, 2019; Merz & Liefbroer, 2012). No gender differences were observed concerning these attitudes, though further investigations are needed in this regard, given the unbalanced gender ratio in our sample.

Participants with children (primarily those having two children) had the most negative attitudes towards childlessness. This particular result seems to be in line with Koropeckyj-Cox and Pendell (2007), who suggested that, generally, people without any children seem to have more positive attitudes towards voluntary childlessness. Also, younger individuals are more likely not to have any children (given their younger age) and have less traditional views concerning the family structure and family planning (given the postmodern social changes); therefore, these findings seem complementary. Another potential explanation for these results concerning significant demographical differences may be related to the economic difficulties that contemporary youth faces, such as increasing levels of inequality and expensive housing (Flynn, 2019), which may determine a more positive view towards voluntary childlessness.

We used a scale that measures the attitudes towards voluntary childlessness concerning women’s and men’s decisions. More specifically, the scale contained items addressing participants’ views of both women’s and men’s decisions not to have any children: “A woman feels complete when she has a child” and “If there is no physical problem, every man should be a father”. However, among the twenty-four items of the scale, seven items refer to the woman’s choice, two items refer directly to men’s choices, while the other fifteen are more general (referring to “couples”, “family”, “individuals”, with no specific related to the potential parent’s gender). Previous studies already suggested that the attitudes concerning voluntary childlessness might be more hostile towards women who decide not to have any children, compared to men (Bays, 2017; Kopper & Smith, 2001), generally due to sexism, which enforces traditional gender roles and underlines men versus women inequalities. Therefore, a potentially interesting suggestion for future research direction might involve alternative measures to voluntary childlessness perception and attitudes, i.e., different scales for measuring voluntary childless men’s attitudes versus voluntary childless women.

Our results suggested that overall sexism, as well as hostile and benevolent sexism, partially mediated the relationship between religiosity and attitudes towards voluntary childlessness. Benevolent sexism was the most powerful predictor of the negative attitude towards voluntary childlessness. As hypothesized, higher levels of religiosity also predicted more negative attitudes concerning childlessness. In other words, the more religious, the less tolerant towards the choice of not having children, and this relationship was partially mediated by benevolent sexism, which praises women who conform to traditional gender roles and norms, such as motherhood. Therefore, though one may expect that, given the costs related to the pronatalist ideology in communist Romania, the contemporary Romanian society might be more open towards one’s choice concerning voluntary childlessness, it seems that the opposite is actually the norm.

In communist Romania, however, religion was not a desirable practice, as the Romanian Communist Party considered religion a capitalist remnant (Stan & Turcescu, 2000). The fact that Romania is, at the current moment, the most religious country in Europe might also be a result of the oppressive communist years, in which people were not entirely free to practice their beliefs. Since the Romanian church, as many others, generally encourage procreation and traditional gender roles and family structures, our results seem to be in line with the related studies that underline the significant links between religiosity, hostile and benevolent sexism, and overall sexism (e.g., Glick et al., 2002; Husnu, 2016; (Koropeckyj-Cox & Pendell, 2007; Taşdemir & Sakallı-Uğurlu, 2009). Finally, several other cultural factors might also explain our results. For example, the fact that younger people in our sample had more positive attitudes concerning voluntary childlessness, compared to older participants, might be explained by van de Kaa’s (1987) Post-Material Values Theory paradigm, suggesting that contemporary society encourages self-realization and individual options, and not traditional systems that generally support the well-being of the family. Nevertheless, further research is needed in this regard.

The are several limits of the current research that need to be addressed. For example, all our measures were self-reported, implying a high possibility of desirable answers. Though the anonymity and confidentiality of participants’ answers were ensured, desirability remains a possibility. Second, as mentioned before, the scale we used might not entirely reflect the attitudes towards men and women who choose voluntary childlessness, but rather the attitudes mostly concerning childless women. Future studies might want to use experimental measures or vignettes for more comprehensive results in this matter. Third, our sample included, as noted above, too few participants to detect eventual small effects of some of the factors we examined, and was also unbalanced in terms of gender. Future studies might want to explore the voluntary childlessness phenomenon and its associated factors in a more extensive, more diverse, and more gender-balanced sample. Also, future studies might want to consider accounting for participants’ specific religion (as we did not assess it), previous procreation experiences (e.g., failed procreation attempts), and socio-economic status, two of the essential factors that might also explain some of our results.

Practical Implications

Our study’s most significant strength is that, to our knowledge, it is the first study to directly address Romanian adults’ attitudes towards voluntary childlessness and its link with religiosity and sexism, in addition to the explored demographic variables. In a transitioning society such as Romania and highly religious, we consider that investigating sensitive topics such as voluntary childlessness is highly important. First, our results add to the theoretical background related to parenthood choices and family structure views. Second, our result highlights the powerful impact of sexism in shaping people’s attitudes towards voluntary childlessness and the strong link between hostile and benevolent sexism and religion. Building on the current results and previous related findings concerning the attitudes towards voluntary childlessness, one of the most important implications from the present study may lie in the practical recommendation for the social message that might be disseminated to decrease prejudicial attitudes towards this choice, by emphasizing that choosing a life without children is a personal, private choice, regardless of one’s reasons or gender, and should not be subject to traditional gender roles, discrimination, and inequity.

Conclusion

The present study is the first to explore the relationship between benevolent sexism, hostile sexism, and religiosity in a Romanian sample. Benevolent sexism seems to be embedded in religiousness, which, in turn, shapes the negative attitudes towards childlessness through the capitalization of traditional gender roles. In addition to using alternative experimental measures to assess the attitudes towards voluntary childlessness, future studies might also investigate other potentially significant related factors. For example, one related research direction might include the use of moral dimensions, such as moral disengagement and moral identity, given the previously documented links between these constructs and prejudicial attitudes (Passini, 2013; Sánchez-Jiménez & Muñoz-Fernández, 2021), religiosity (Sverdlik & Rechter, 2020), and sexism (Paciello et al., 2019). Additionally, further investigations concerning the attitudes towards voluntary childlessness might benefit from including personality assessments and media portrayals of childfree couples (Kaklamanidou, 2019).

Data Availability

The raw data supporting this article’s conclusions will be made available by the authors without undue reservations.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Abma, J. C., & Martinez, G. M. (2006). Childlessness among older women in the United States: Trends and profiles. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 1045–1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00312.x

Ahmadi, S. E., Rafiey, H., Sajjadi, H., & Nosratinejad, F. (2019). Explanatory model of voluntary childlessness among Iranian couples in Tehran: A grounded theory approach. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences, 44(6), 449–456. https://doi.org/10.30476/ijms.2019.44964

Ashburn-Nardo, L. (2017). Parenthood as a moral imperative? Moral outrage and the stigmatization of voluntarily childfree women and men. Sex Roles, 76, 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0606-1

Avison, M., & Furnham, A. (2015). Personality and voluntary childlessness. Journal of Population Research, 32, 45–67. https://doi.org/. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-014-9140-6

Bădescu, G., Comşa, M., Sandu, D., & Stănculescu, M. (2007). Barometrul de Opinie Publică 1998–2007 [Barometer for Public Opinion 1998–2007]. SOROS Foundation.

Bello, F. A., Akinajo, O. R., & Olayemi, O. (2014). In-vitro fertilization, gamete donation and surrogacy: Perceptions of women attending an infertility clinic in Ibadan, Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 18(2), 127–133.

Berelson, B. (1979). Romania’s 1966 anti-abortion decree: The demographic experience of the first decade. Population Studies, 33(2), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.1979.10410438

Burn, S. M., & Busso, J. (2005). Ambivalent sexism, scriptural literalism, and religiosity. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 412–418. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00241.x.

CBS/AP (2014). Dropping birth rates threaten global economic growth. Retrieved from http://www.cbsnews.com/news/droppingbirth-rates-threaten-global-economic-growth/

Crittenden, A. (2001). The price of motherhood: Why the most important job in the world is still the least valued. Metropolitan Books.

Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112, 1297–1338.

Demeny, E. (2017). Networks of reproduction: Politics and practices surrounding surrogacy in 486 Romania. In M. Davies (Ed.), Babies for Sale? Surrogacy, human rights and the politics of reproduction. Zed Books.

Dever, M., & Saugeres, L. (2004). I forgot to have children! Untangling links between feminism, careers and voluntary childlessness. Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, 6(2), 116–126.

DeOllos, I. Y., & Kapinus, C. A. (2002). Aging childless individuals and couples: Suggestions for new directions in research. Sociological Inquiry, 72, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-682X.00006

European Commssion (2019). Romania: Population: Demographic situation, official language, and religions. https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/population-demographic-situation-languages-and-religions-64_ro

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Flynn, L. B. (2019). The young and the restless: housing access in the critical years. West European Politics, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1603679

Frejka, T., & Calot, G. (2001). Cohort reproductive patterns in low-fertility countries. Population and Development Review, 27, 103–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2001.00103.x

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., & Castro, Y. R. (2002). Education and Catholic religiosity as predictors of hostile and benevolent sexism toward women and men. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 47(9–10), 433–441. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021696209949.

Glick, P., Sakallı-Uğurlu, N., Akbaş, G., Orta, I. M., & Ceylan, S. (2016). Why do women endorse honor beliefs? Ambivalent sexism and religiosity as predictors. Sex Roles, 75, 543–554. https://doi.org/. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0550-5

González, MJ., & Jurado-Guerrero, T. (2006). Remaining childless in affluent economies: a comparison of France, West Germany, Italy and Spain, 1994–2001. Rester sans enfant dans des sociétés d'abondances: une comparaison de la France, l'Allemagne de l'Ouest et l'Espagne, 19994–2001. European Journal of Population, 22, 317–352. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-006-9000-y.

Götmark, F., & Andersson, M. (2020). Human fertility in relation to education, economy, r eligion, contraception, and family planning programs. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 265. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8331-7.

Grunberg, P., Miner, S., & Zelkowitz, P. (2020). Infertility and perceived stress: The role of identity concern in treatment-seeking men and women. Human Fertility, 5, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647273.2019.1709667

Hakim, C. (2002). A new approach to explaining fertility patterns: Preference theory. Population and Development Review, 29(3), 349–373.

Hakim, C. (2005). Childlessness in Europe: Research report to the Economic and Social Research Council (10/03/2005), available at: http://www.esrc.ac.uk/my-esrc/grants/RES-000-230074/read.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional Process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F., & Scharkow, M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science, 24(10), 1918–1927.

Hayford, S. R., & Morgan, S. P. (2008). Religiosity and fertility in the United States: The role of fertility intentions. Social forces; a Scientific Medium of Social Study and Interpretation, 86(3), 1163–1188 https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0000

Holton, S., Fisher, J., & Rowe, H. (2009). Attitudes toward women and motherhood: Their role in Australian women’s childbearing behavior. Sex Roles, 61, 677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9659-8

Hord, C., David, H. P., Donnay, F., & Wolf, M. (1991). Reproductive health in Romania: Reversing the Ceausescu legacy. Studies in Family Planning, 22(4), 231. https://doi.org/10.2307/1966479

Huber, S. (2003). Zentralität und Inhalt. Ein neues multidimensionales Messinstrument der Religiosität (Vol. 9). Leske & Budrich.

Husnu, S. (2016). The role of ambivalent sexism and religiosity in predicting attitudes toward childlessness in Muslim undergraduate students. Sex Roles, 75(11–12), 573–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0639-5

Igreja, A. R., & Ricou, M. (2019). Surrogacy: Challenges and ambiguities. The new bioethics. A Multidisciplinary Journal of Biotechnology and the Body, 25(1), 60–77. https://doi.org/. https://doi.org/10.1080/20502877.2019.1564007

Kaklamanidou, B.-D. (2019). The voluntarily childless heroine: A postfeminist television oddity. Television & New Media, 20(3), 275–293. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476417749743.

Kelly, M. (2010). Women's voluntary childlessness: A radical rejection of motherhood? WSQ: Women's Studies Quarterly, 37, 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.0.0164

Kopper, B. A., & Smith, M. S. (2001). Knowledge and attitudes toward infertility and childless couples. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31, 2275–2291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00175.x

Koropeckyj-Cox, T., & Pendell, G. (2007). Attitudes about childlessness in the United States: Correlates of positive, neutral, and negative responses. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 1054–1082. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X07301940

Lachance-Grzela, M., & Bouchard, G. (2010). Why do women do the lion’s share of housework? A decade of research. Sex Roles, 63, 767–780.

Lawrence, E., Cobb, R. J., Rothman, A. D., Rothman, M. T., & Bradbury, T. N. (2008). Marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 41–50.

Letherby, G. (2002). Childless and bereft?: Stereotypes and realities in relation to ‘voluntary’ and ‘involuntary’ childlessness and womanhood. Sociological Inquiry, 72(1), 7–20.

Livingston, G., & Cohn, D. (2010). Childlessness up among all women; down among women with advanced Degrees. Pew Research Centre. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2010/06/25/childlessness-up-among-all-women-down-among-women-with-advanced-degrees/

Maftei, A., & Holman, A.C. (2020). Moral women, immoral technologies? Romanian Women’s perceptions of assisted reproductive technologies versus adoption. The New Bioethics. A Multidisciplinary Journal of Biotechnology and the Body, 26(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/2050287.

Mahoney, A. (2005). Religion and conflict in marital and parent – Child relationships. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 689–706 7.2020.1796256.

Marinescu, R.-E. (2020). The myth of motherhood in communist and Postcommunist Romania: From pro-Natalist policies to neoliberal views. In R. Ciolaneanu & R.-E. Marinescu (Eds.), Handbook of research on translating myth and reality in women imagery across disciplines. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-6458-5

McQuillan, K. (2004). When does religion influence fertility? Population and Development Review, 30(1), 25–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2004.00002.x

Merz, E. M., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2012). The attitude toward voluntary childlessness in Europe: Cultural and institutional explanations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 587–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00972.x

Mills, M., Rindfuss, R. R., McDonald, P., & te Velde, E. (2011). Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Human Reproduction Update, 17, 848–860.

Mills, M. C., Tanturri, M. L., Rotkirch, A., Sobotka, T., Takacs, J., Miettinen, A., Faludi, C., Kantsa, V., & Nasiri, D. (2015). State-of-the-art report childlessness. Families And Societies, 32.

Mitnick, D. M., Heyman, R. E., & Smith Shep, A. M. (2009). Changes in relationship satisfaction across the transition to parenthood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 848–852.

Mikołajczak, M., & Pietrzak, J. (2014). Ambivalent sexism and religion: Connected through values. Sex Roles, 70(9), 387–399. https://doi.org/. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0379-3

Mollen, D. (2013). Reproductive rights and informed consent: Toward a more inclusive discourse. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 14, 162–182.

Moulasha, K., & Rao, G. R. (1999). Religion-specific differentials in fertility and family planning. Economic and Political Weekly, 34(42/43), 3047–3051.

Napier, J. L., Thorisdottir, H., & Jost, J. T. (2010). The joy of sexism? A multinational investigation of hostile and benevolent justifications for gender inequality and their relations to subjective well-being. Sex Roles, 62, 405–419. https://doi.org/. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9712-7

Noordhuizen, S., de Graaf, P., & Sieben, I. (2010). The public acceptance of voluntary childlessness in the Netherlands: From 20 to 90 per cent in 30 years. Social Indicators Research, 99, 163–181. https://doi.org/. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9574-y

Paciello, M., D'Errico, F., & Saleri, G. (2019). Moral struggles in social media discussion: The case of sexist aggression. SAT@SMC. http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2474/shortpaper3.pdf

Passini, S. (2013). What do I think of others in relation to myself? Moral identity and moral inclusion in explaining prejudice. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23(3), 261–269. https://doi.org/. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2117

Peri-Rotem N. (2016). Religion and fertility in Western Europe: Trends across cohorts in Britain, France and the Netherlands. European Journal of Population = Revue europeenne de demographie, 32(2), 231–265. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-015-9371-z.

Pinter, B., Hakim, M., Seidman, D. S., Kubba, A., Kishen, M., & Di Carlo, C. (2016). Religion and family planning. The European journal of contraception & reproductive health care: the official journal of the European Society of Contraception, 21(6), 486–495 https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2016.1237631

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Purewal, S., & Van den Akker, O. (2007). The socio-cultural and biological meaning of parenthood. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, 28(2), 79–86. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1080/01674820701409918.

Rijken, A. J., & Merz, E.-M. (2014). Double standards: Differences in norms on voluntary childlessness for men and women. European Sociological Review, 30(4), 470–482. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu051

Sakallı-Uğurlu, N., Türkoğlu, B., Kuzlak, A., & Gupta, A. (2018). Stereotypes of single and married women and men in Turkish culture. Current Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9920-9.

Sánchez-Jiménez, V., & Muñoz-Fernández, N. (2021). When are sexist attitudes risk factors for dating aggression? The role of moral disengagement in Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041947

Sobotka, T. (2009). Sub-replacement fertility intentions in Austria. European Journal of Population, 25, 387–412.

Stan, L., & Turcescu, L. (2000). The Romanian orthodox church and post-communist democratisation. Europe-Asia Studies, 52(8), 1467–1488. https://doi.org/10.1080/713663138

Sverdlik, N., & Rechter, E. (2020). Religious and secular roads to justify wrongdoing: How values interact with culture in explaining moral disengagement attitudes. Journal of Research in Personality, 87, 103981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103981

Tanturri, M. L., & Mencarini, L. (2008). Childless or childfree? Paths to voluntary childlessness in Italy. Population and Development Review, 34, 51–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00205.x

Taşdemir, N., & Sakallı-Uğurlu, N. (2010). The relationships between ambivalent sexism and religiosity among Turkish university students. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 62(7–8), 420–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9693-6

Testa, M. R. (2012). Family sizes in Europe: Evidence from the 2011 Eurobarometer survey. European demographic research papers 2. : Vienna Institute of Demography of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Vidad, F. C. (2009). Mental health professionals’ perceptions of voluntarily childless couples. Dissertations & Theses, 126 http://aura.antioch.edu/etds/126

van de Kaa, D. J. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Bulletin, 42, 1–59.

Vinson, C., Mollen, D., & Smith, N. G. (2010). Perceptions of childfree women: The role of perceivers’ and targets’ ethnicity. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 20, 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.1049

Whitehead, B. D. (2006). The state of our unions, 2006: The social health of marriage in America (National Marriage Project Report). Rutgers University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Statement

This study’s protocol was designed in concordance with ethical requirements specific to the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University (Iasi, Romania), before beginning the study and supervised by Alexandra Maftei. All participants voluntarily participated in the study and gave written informed consent following the Declaration of Helsinki and the national laws from Romania regarding ethical conduct in scientific research, technological development, and innovation.

• No animal studies are presented in this manuscript.

• Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

The authors declare no financial interests/personal relationships, which may be considered as potential competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This study’s protocol was designed and approved by the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University (Iasi, Romania), before beginning the study and supervised by Alexandra Maftei.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maftei, A., Holman, AC. & Marchiș, M. Choosing a life with no children. The role of sexism on the relationship between religiosity and the attitudes toward voluntary childlessness. Curr Psychol 42, 11486–11496 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02446-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02446-4