Abstract

Academic burnout and engagement are important indicators of students’ school success. This short-term longitudinal study examined whether parenting styles and parental involvement (parent report, collected at Time 1) predicted adolescent-reported academic burnout and engagement (collected at Time 3, two months later) directly or indirectly via adolescents’ perceived parental support (collected at Time 2, one month later). A total of 285 Chinese high school students (M = 15.93 years, SD = 1.06 years, 51.9% boys) and their fathers and mothers participated in the survey over three time points (one month apart for each data collection). Path analysis results indicated that authoritative parenting predicted less academic burnout in adolescents. Perceived paternal support mediated the relations between paternal authoritative parenting and adolescents’ academic engagement. Parents’ knowledge and skills involvement positively predicted adolescents’ perceived support, which in turn, predicted more academic engagement. However, father’s time and energy involvement predicted lower perceived paternal support, especially for boys. Moreover, multi-group analysis suggested that fathers and mothers influenced boys’ and girls’ academic burnout and engagement differently. In conclusion, it is important to consider adolescents’ perception of parental support, their developmental needs, and gender roles in Chinese families in order to increase adolescents’ academic engagement and decrease students’ academic burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Academic stress is common among high school students. For example, 54.9% secondary school students in China reported experiencing academic burnout (Zhang et al., 2013). Academic burnout describes students’ state of feeling exhausted, having cynical and detached attitudes to their learning, and feeling incompetent as a student (Schaufeli et al., 2002). In contrast, some students still display high levels of academic emotional engagement, which reflects students’ emotional commitment to their study-related activities (e.g., assignments) and experiences of an increased concentration on tasks, with the perception of “time flying” (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Academic burnout is associated with compromising students’ academic achievement and well-being, whereas academic engagement is associated with promoting students’ self-efficacy and academic achievement (Cadime et al., 2016; Lay-Khim & Bit-Lian, 2019; Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, 2014). As a result, it is essential to study risk and protective factors for high school students’ academic burnout and academic engagement.

Researchers suggest that parenting practices (e.g., warmth, harsh punishment) and parental involvement (e.g., help with homework, communicate with teachers, volunteer at schools) influence students’ academic burnout and academic engagement (Li & Gan, 2011; Wang & Sheikh-Khalil, 2014; Wilder, 2014). However, little research has explored the underlying psychological processes that account for associations between parenting practices, parental involvement, and youth academic outcomes. In addition, most existing studies on parenting focus exclusively on mothers and ignore the important contribution of fathers (Cabrera, 2020). Moreover, the existing evidence between parenting practices and adolescents’ academic burnout and academic engagement is mainly based on Western samples. Given the unique cultural context of parenting in Chinese families, more study is needed to unpack how parenting influences Chinese youth outcomes (Cheah et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2019). Furthermore, to address gaps above, the current study aims to examine the mechanism of how paternal and maternal parenting practices predict Chinese adolescents’ academic burnout and academic engagement, as well as potential gender differences using a short-term longitudinal study based on reports from fathers, mothers, and adolescents.

Academic Engagement and Academic Burnout

Students’ engagement is a multidimensional concept, in which different facets (e.g., behavioral, emotional, and cognitive components) work together to indicate a positive and fulfilling state to learning (e.g., vigor, dedication, and absorption; Schaufeli et al., 2002; Skinner et al., 2009). The current study focused on emotional engagement in this study. Many studies have revealed that burnout and emotional engagement are independent but negatively related phenomena (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Thus, core dimensions of academic engagement (i.e., vigor, dedication; Cadime et al., 2016) and academic burnout (i.e., exhaustion, cynicism; Cadime et al., 2016) were examined independently. Vigor describes students with high levels of energy and mental resilience while studying, who are willing to devote effort to their learning. Dedication refers to students feeling enthusiastic, inspired, and challenged while learning (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Exhaustion is characterized as feeling depleted of one’s emotional and physical resources. Cynicism indicates a negative, callous, and detached attitude towards schoolwork (Schaufeli et al., 2002).

Theoretical Framework

According to ecological systems theory, a child’s development takes place through the complex reciprocal interactions between the child and his or her environment (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994). The child’s environment encompasses more immediate social context in microsystem (e.g., family, school, and neighborhood), mesosystem (the interaction between family and schools, e.g., parental involvement in schools), exosystem (e.g., parent work place), as well as indirect influences from macrosystem, including cultural values, customs, and laws. Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2006) further enhanced the original theory in their process-person-context-time (PPCT) model, which emphasizes that the microsystem is closely associated with the macrosystem, and both of them have the most significant effects on children. For example, family and schools can influence students’ resilience and adjustment (Chen et al., 2015; Gamble & Crouse, 2020). Additionally, cultural processes can permeate in the interactions between the child and parent as cultural values reflected in parents’ childrearing beliefs, and socialization goals may shape parenting practices and child developmental outcomes (Chen et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2019). Traditional Chinese culture is rooted in Confucianism that greatly emphasizes social hierarchy; academic success is regarded as a primary way to pursue upward mobility and is strongly associated with personal career success (Shih, 2015). Moreover, families’ prevailing divisions of gender roles and gendered socialization in Chinese society lead to different roles by mothers and fathers at home and their interactions with boys vs. girls. For example, Chinese parents tend to be more supportive to girls than to boys (Xie & Li, 2018). This phenomenon has been passed down orally as the Chinese folk wisdom says, ‘be strict to the boy but caring to the girl (qiong yang er zi fu yang nv).’ Parental involvement in children’s education (e.g., communicating with teachers, volunteering at schools) is part of the mesosystem linking family and school systems. Parenting practices and parental involvement may impact child outcomes through the child’s perception of the quality of parent-child relationship. So, it is important to examine adolescents’ perception of parent-child relationship in addition to parenting practice on adolescent adjustment (Cummings & Warmuth, 2019).

Parenting and Adolescent’s Perceived Parental Support in Chinese Context

As addressed in the PPCT model, cultural and ethnic background influence one’s development (An et al., 2019). Cultural differences can also shape different parenting practices and impact how children interpret certain parenting practice. In other words, similar parenting practice may have different meanings for children from different cultural backgrounds, which may have different effects on children’s outcomes (Ng & Wang, 2019). Contemporary parenting practices in Chinese families reflect both traditional and modern cultural contexts. In a traditional Chinese context, children are expected to meet their family’s expectations while self-expression and autonomy are discouraged (Fuligni, 1998). On the other hand, Chao (1994) argued that for Chinese parents, controlling and high-power parenting were typically associated with parental care and warmth. Explicit expression of intimacy (e.g., “hugging and kissing”) is considered inappropriate in traditional Chinese culture, and Chinese parents tended to express warmth indirectly through guidance, and educational opportunities (e.g., “I will try to let her go to good schools”; Cheah et al., 2015). There are many cultural factors permeating in dyadic interactions between parents and adolescents, so understanding the adolescents’ perception in interpreting parents’ expression of care is essential for understanding how the meaning of parenting may affect adolescent outcome differently. Moreover, recent studies have found that urban Chinese parents are becoming more supportive and more authoritative and prioritizing child’s social-emotional adjustment (Zhang et al., 2017). They are more likely to use strategies that promote children’s freedom and not pressuring children to engage in particular activities (Way et al., 2013). Therefore, more study is needed to unpack the multifaceted aspects of parenting in Chinese families.

Parenting Style, Parental Involvement, and Academic Outcomes

Parenting has been linked to youth’s academic engagement (Li & Gan, 2011). Many studies revealed that youth with authoritative parents (high warmth and high control) tended to be more competent, better adjusted emotionally, highly engaged in school, and showed fewer problem behaviors across Western and Chinese cultures (Baumrind et al., 2010; Li & Gan, 2011). In one study, Chinese students who experienced more academic burnout reported that their parents expressed less warmth and practiced more harsh, rejecting, or overprotective parenting practices (Li & Gan, 2011). While negative outcomes of authoritarian (low warmth but high control) parenting have been demonstrated (Baumrind et al., 2010), the role of authoritarian parenting on youth academic outcomes needs further investigation in Chinese context.

Another dimension of parenting is parental involvement, which is defined as parents’ investment and commitment to their children, including time, energy, and money, and active interactions with schools (Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994). According to Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler (1995), parental involvement entails two important components, namely parental knowledge and skills, and time and energy related to being involved in children’s education. Parents may experience constraints by job demands and may lack energy to help their children to work through homework or to attend special events at school (Hill & Taylor, 2004). Parents also differ in their knowledge and skills to navigate the school system in order to get involved effectively (e.g., how to communicate effectively with teachers and volunteer at school). Nonetheless, studies have found that parental involvement contributes to youth’s academic performance (Wilder, 2014) and academic engagement (Fan & Williams, 2010). Parental involvement also effectively protects youth from academic burnout (Li et al., 2018).

Adolescents’ Perceived Parental Support as a Mediator

Perceived parental support may be the underlying psychological processes accounting for these associations between parenting practices and youth learning outcomes. The attachment theory suggests that parenting practices are closely associated with children’s perception of the quality parent-child relationship, such as perceived parental support and security (Cummings & Warmuth, 2019). Adolescents’ perception of parenting practices affects their willingness to accept or defy parents’ involvement or support (Soenens et al., 2019). Additionally, few empirical studies examined the associations between perceived parental involvement and perceived parental support (e.g., Ruholt et al., 2015), with the majority only using one data source (e.g., only child-reported; Dinkelmann & Buff, 2016). Thus, the current study extends prior research by examining adolescent perception of parental support as a key mechanism to explain how mother- and father-reported parenting practices impact youth learning outcomes.

Gender Differences and Dyadic Patterns

Parents’ and youths’ gender, and their interactions influence the relations between parenting practices and youth outcomes. According to the social role theory (Eagly et al., 2000), prevailing divisions of gender roles in society lead to different gender functions and roles by mothers and fathers. For example, research showed that mothers spend more time with their children, are more involved, and are more sensitive to their needs than fathers (Hallers-Haalboom et al., 2014). Nonetheless, fathers also play an irreplaceable role in their children’s lives (Cabrera, 2020). Moreover, paternal and maternal parenting practices have different effects on adolescents (Milevsky et al., 2007; Padilla-Walker et al., 2016). For example, mother’s warmth was associated with adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward family, while father’s warmth was associated with prosocial behavior toward friends (Padilla-Walker et al., 2016).

Additionally, from a transactional perspective, both parents and their children are active agents in the parent-adolescent relationship. Adolescent’s gender can influence parenting, and parents often apply different parenting practices on boys and girls. For example, parents are warmer and more empathetic with their daughters than sons, and parents are more likely to validate their daughters’ emotions than sons’ (Lambie & Lindberg, 2016; Mascaro et al., 2017). Furthermore, boys and girls also have different responses to parenting practices, showing different sensitivity to parenting, with adolescent girls being more sensitive to the emotional closeness with their parents than boys (Lewis et al., 2015).

With the noticeable interactions between parents’ gender and youth’s gender, the effects of different dyads (mother-son, mother-daughter, father-son, and father-daughter) on adolescent outcomes may differ (Brown & Tam, 2019). For example, a meta-analysis of 126 studies revealed that mothers used more psychological control and harsh physical discipline with boys than girls because of gender socialization and gender schema (Endendijk et al., 2016). Mothers of 7–16 years old daughters were rated by researchers as more empathetic, warm, accepting, and less negative than mothers of sons in observed parent-child interactions (Mandara et al., 2012), whereas there were no differences in father-son and father-daughter interactions (Piko & Balázs, 2012). Paternal warmth strengthened the negative relation between parental monitoring and school trouble, and the relation was stronger for 6th to 8th grade boys than girls (Lowe & Dotterer, 2013). Therefore, the current study examined the associations between paternal and maternal parenting and adolescent learning outcomes separately across different dyads.

Current Study

The current study addressed gaps in the literature in four ways. First, few researchers have examined students’ academic burnout and engagement concurrently among Chinese adolescents, which are important indicators of school success. Second, to date, little research has investigated the youth’s microsystem (perceived parental support) and mesosystem (parental involvement in schools) in relation to students’ academic burnout and engagement. Third, few studies has examined how parents’ and youths’ gender, and their interactions may have influences on the relations between parenting practices and children’s outcomes. Fourth, few studies of parents’ practices and school success focus on Chinese adolescents and their parents.

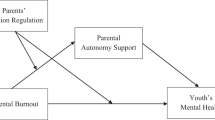

Therefore, the current study seeks to: (a) investigate the roles of parenting style and parental involvement on Chinese adolescents’ academic burnout and engagement; (b) examine the mediating role of adolescents’ perceived parental support; and (c) explores the gender differences in how parenting processes impact adolescents’ youth academic burnout and engagement across gendered-paired dyads. We hypothesized that authoritative parenting and high parental involvement would positively predict adolescents’ academic engagement and negatively predict academic burnout. In contrast, authoritarian parenting would negatively predict adolescents’ academic engagement and positively predict academic burnout. Adolescents’ perceived parental support would mediate these relations. Lastly, these relations were expected to differ among mother-daughter, mother-son, father-daughter, and father-son dyads.

Method

Procedures

The data were collected from a high school in Hengyang, China in 2015. The project was approved by the Committee for Protecting Human and Animal Subjects of Peking University. Both parent consents and adolescent assents were obtained. Figure 1 showed the data collection process. At Time 1, fathers and mothers of the same adolescent each completed surveys on parenting style, parenting involvement, and demographic information. Surveys were distributed to parents during the parent-teacher conference. A month later, at Time 2, adolescents completed a survey on perceived parental support. Another month later, at Time 3, adolescents completed surveys on academic burnout and academic engagement. Participation was voluntary, and no incentive was provided. Response rate was 78.5% at Time 1. Surveys from 322 parents and 311 of their adolescents were returned. Data from eleven adolescents were excluded from the analysis because 75% items were missing. Data from another 15 adolescents were excluded from the analysis because they only completed one wave of data collection. We only included parent data in the analysis when we had valid data from their adolescents.

Participants

A total of 285 high school students (27.4% 10th graders, 42.5% 11th graders, and 30.2% 12th graders, M = 15.93 years, SD = 1.06 years, 51.9% boys) in the city of Hengyang, China, and their parents participated in this study. For fathers, 84.9% had high school/junior college or less education background, 9.8% held a Bachelor’s, and 1.4% held a Master’s degree. For mothers, 89.1% had high school/junior college or less education background, 7.0% held a Bachelor’s, and 0.4% held a Master’s degree. Approximately 92.6% fathers and 88.4% mothers were employed. Fathers worked 8.62 h (SD = 2.74 h), and mother worked 8.04 h (SD = 3.39 h) a day. Fathers reported that they spent 1.10 h (SD = 1.03 h) and mothers spent 1.15 h (SD = 0.92 h) per day supporting their adolescents with school work. Additionally, about 60% (n = 168) of adolescents reported that fathers and mothers were equally involved in their schooling; 12.6% (n = 36) or 22.8% (n = 65) of adolescents reported fathers or mothers as being mainly involved; 3.86% (n = 11) of adolescents referenced the other guardian to be mainly involved.

Measures

Academic Burnout

The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey Chinese version (MBI-SS; Hu & Schaufeli, 2009; Schaufeli et al., 2002) was used to assess adolescents’ academic burnout. Two core dimensions were assessed: exhaustion (e.g., “I feel emotionally drained by my studies.” 5 items; α = 0.80) and cynicism (e.g., “I have become less enthusiastic about my studies.” 4 items; α = 0.75). Adolescents responded on a 7-point scale (1 = never, 7 = every time). In the current study, CFA showed that the model fit was good, χ2 = 68.05, df = 32, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06, and SRMR = .03.

Academic Engagement

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-Student Chinese version (UWES-S; Li & Huang, 2010; Schaufeli et al., 2002) was used to measure adolescents’ academic engagement. Two core dimensions were assessed on a 7-point scale (1 = never, 7 = every time): vigor (e.g., “When studying I feel strong and vigorous.” 5 items; α = 0.85) and dedication (e.g., “I am enthusiastic about my studies.” 5 items; α = 0.80). In the current study, CFA demonstrated a good model fit, χ2 = 51.72, df = 26, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06, and SRMR = .03.

Parenting Styles

Fathers and mothers of the same adolescent separately completed The Parental Authority Questionnaire Chinese version (Zhou et al., 2010) to measure parenting styles. Authoritative (e.g., “My children know what I expect from them, but feel free to talk with me if they feel my expectations are unfair.” 5 items) and authoritarian (e.g., “It is for my children’s own good to require them to do what I think is right, even if they don’t agree.” 5 items). Each parent reported on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). In the current study, the model fit of paternal and maternal parenting styles were good, χ2 = 65.20/62.50, df = 33/30, CFI = .94/.95, RMSEA = .06/.06, and SRMR = .06/.06. The internal consistencies of authoritative (α = 0.76 for fathers, 0.77 for mothers) and authoritarian parenting (α = 0.74 for fathers, 0.73 for mothers) were acceptable.

Parental Involvement

Fathers and mothers of the same adolescent responded separately to two subscales of the Parental Involvement scale (Walker et al., 2005) to measure two types of parental involvement: knowledge and skills (e.g., “I know how to communicate with my child’s teacher effectively.” “I know how to help my child with homework.” 9 items) and time and energy (e.g., “I have enough time and energy to help my child with homework.” 6 items). Each parent reported on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). In the current study, the model fit of paternal and maternal parental involvement were acceptable, χ2 = 168.22/ 153.08, df = 64/62, CFI = .95/.95, RMSEA = .08/.07, and SRMR = .05/.05. The internal consistency of knowledge and skills (α = 0.84 for fathers, 0.81 for mothers) and time and energy involvement (α = 0.86 for fathers, 0.84 for mothers) were good.

Perceived Parental Support

The scale was revised from Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (Eisenberger et al., 2002), which included five items of adolescents’ perception of parental emotional supports (e.g., “My father does care about my well-being.”). Adolescents reported on their perceived paternal and maternal support separately on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). In the current study, the models of perceived paternal and maternal support were good, χ2 = 5.34/ 5.40, df = 3/4, CFI = .997/ .998, RMSEA = .052/ .035, and SRMR = .014/ .014. The internal consistencies were good (α = 0.88 for paternal support, 0.87 for maternal support).

Analysis Approach

A limited number of the participants skipped a few items. The Little’s MCAR test in SPSS 26 was used to test whether the data were missing completely at random (Myers, 2011). The result revealed that the missing data were random, and there was no pattern in the missing data, χ2 (183687) = 59,820.637, p = 1.000. To examine the mediation model, a path analysis using a full information likelihood on Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) with 5000 bootstrap was conducted. The path or indirect effect was considered to be significant if the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) did not contain a zero. And the path or indirect effect was considered to be marginally significant if the 90% CIs did not contain a zero when 95% CI included zero, in which case the 90% CI for these paths were reported. Separate models for fathers and mothers were run first. Then, a multi-group path analysis was used to examine whether paternal or maternal parenting practices associated with boys’ and girls’ school outcomes differently. Then father-son and father-daughter dyads in the paternal model and mother-son and mother-daughter in the maternal model were compared.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Approximately 46.3% of students in this sample frequently (mean score > 4) felt exhausted, and 29.5% of students had a cynical attitude towards studying frequently. On the other hand, 29.1% of students frequently felt vigorous while studying, and 51.2% of students frequently felt dedicated. About 18.2% (n = 52) of students frequently experienced both academic engagement (mean score > 4) and academic exhaustion (mean score > 4). Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlation for the variables of interest (i.e., parenting styles, parental involvement, perceived parental support, academic engagement, academic burnout).

A series of independent-samples t-test examined youth gender differences on academic outcomes (academic burnout and engagement), parenting practices (parenting styles and parental involvement), and perceived parental support. Boys reported a higher level of academic exhaustion (Mdifference = 0.338, t(283) = 2.994, p = .003) and cynicism (Mdifference = 0.331, t(283) = 2.917, p = .003) than girls. There were no differences in the scores of paternal and maternal parenting styles, parental involvement, and perceived parental support between boys and girls. The paired-sample t-tests were used to examine the differences between paternal and maternal parenting. The results showed that, for the same child, their mother reported higher scores on parental involvement and authoritative parenting (For time and energy: Mdifference = 0.166, t(284) = 2.234, p = .026; For knowledge and skills: Mdifference = 0.184, t(284) = 2.882, p = .004; For authoritative parenting: Mdifference = .128, t(284) = 1.893, p = .059) than their father. Both fathers and mothers reported using more authoritative parenting than authoritarian parenting (Mdifference = 0.940/ 1.152, t(284) = 10.017/ 12.604, p < .001/ p < .001). Adolescents perceived more maternal support than paternal support (Mdifference = 0.258, t(284) = 5.782, p < .001). Additionally, compared with their peers (n = 112), students who reported fathers and mothers were equally involved in their schooling (n = 168), perceived more paternal and maternal support (t(283) = 2.663/2.438, p = .008/.015) and had higher academic dedication (t(283) = 2.173, p = .031).

Mediation

In the paternal model (see Fig. 2a), paternal authoritative parenting predicted less academic exhaustion, β = − .181, 95% CI [−.319, −.043], and academic cynicism in adolescents, β = − .190, 95% CI [−.356, −.024]. Paternal knowledge and skills involvement predicted greater academic vigor, β = .177, 95% CI [.004, .351]. Surprisingly, paternal time and energy involvement predicted lower perceived paternal support, β = − .197 95% CI [−.370, −.023]. In the maternal model (see Fig. 2b), maternal authoritarian parenting was marginally significant in predicting more academic exhaustion in adolescents, β = .122 90% CI [.020, .224], but time and energy involvement predicted less academic exhaustion, β = − .167 95% CI [−.326, −.008]. Maternal authoritative parenting predicted less academic cynicism in adolescents, β = − .155 95% CI [−.301, −.010].

Indirect effects of parental parenting and involvement on adolescents’ academic outcomes. A. Father Indirect Effect. Paternal authoritative parenting on academic vigor via perceived paternal support .050 95%CI [.005 .096]. Paternal authoritative parenting on academic dedication via perceived paternal support .062 95%CI [.018 .107]. Paternal knowledge and skills on academic vigor via perceived paternal support .043 90%CI [.003 .084]. Paternal knowledge and skills on academic dedication via perceived paternal support .056 95%CI [.003 .110]. B. Mother Indirect Effect. Maternal authoritative parenting on academic vigor via perceived paternal support .036 90%CI [.000 .072]. Maternal authoritative parenting on academic dedication via perceived paternal support .036 90%CI [.000 .073]. Note. Solid lines indicate significant paths (p < .05), and dash lines indicate marginally significant paths (.10 < p < .05). †p < .10 * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001

Parent-report of parenting practice and parental involvement were associated with adolescent-report of their academic outcomes via adolescent-perceived parental support (see Fig. 2a, b). Specifically, paternal authoritative parenting had indirect effects on adolescents’ academic vigor and dedication (indirect effect = .050/.062, 95% CI [.005, .096]/ [.018, .107], respectively) via adolescent-perceived paternal support. Paternal knowledge and skills involvement also had indirect effects on adolescents’ academic dedication (indirect effect = .056, 95% CI [.003, .110]) via adolescent-perceived paternal support. Although maternal authoritative parenting did not have significant indirect effects on adolescents’ school adjustment, maternal authoritative parenting and knowledge and skills involvement predicted more adolescent-perceived maternal support, β = .225/ .272, 95% CI [.105, .340]/ [.116, .442], respectively. In sum, paternal and maternal authoritative parenting and knowledge and skills involvement positively predicted adolescents’ perceived support, and when adolescents perceived more paternal support, they reported more academic vigor and dedication. Paternal and maternal authoritative parenting also predicted less academic cynicism. Maternal authoritarian parenting only marginally (.05 < p < .10) significantly predicted academic exhaustion.

Gender Differences

Father-Son and Father-Daughter Dyads

Fathers’ parenting practices predicted sons’ and daughters’ learning outcomes differently (see Fig. 3a, b). Fathers’ authoritative parenting only directly and negatively predicted their sons’ (not their daughters’) academic exhaustion (β = − .212, 95% CI [−.406, −.017]) and cynicism (β = − .284, 95% CI [−.504, −.064]). Additionally, paternal authoritative parenting positively predicted perceived paternal support for both son and daughters (β = .216/.340, 95% CI [.032, .400]/ [.184, .496]), and when son and daughters perceived more paternal support, they reported more academic dedication (β = .231/.232, 95% CI [.033, .428]/ [.064, .400]). This indirect effect of paternal authoritative parenting on daughters’ academic dedication was .079, 95% CI [.012, .145]. However, the indirect effect of paternal authoritative parenting on son’s academic dedication was marginally significant, .052 90% CI [.005 .099].

Indirect effects of paternal parenting and involvement on boys’ and girls’ academic outcomes. A. Father- Son Dyad Indirect Effect. Paternal authoritative parenting on academic vigor via perceived paternal support .052 90%CI [.005 .099]. Paternal knowledge and skills on academic vigor via perceived paternal support .070 90%CI [.005 .135]. Paternal authoritative parenting on academic dedication via perceived paternal support .050 90%CI [.001 .099]. B. Father- Daughter Dyad Indirect Effect. Paternal authoritative parenting on academic dedication via perceived paternal support .079 95%CI [.012 .145]. Note. Solid lines indicate significant paths (p < .05), and dash lines indicate marginally significant paths (.10 < p < .05). †p < .10 * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001

As for paternal involvement, fathers’ knowledge and skills involvement directly and positively predicted their daughter’s academic vigor (β = .409, 95% CI [.111, .708]) and marginally and indirectly predicted their son’s academic vigor (.070, 90% CI [.005 .135]). Additionally, paternal involvement significantly predicted only their sons’ (not their daughters’) perceived paternal support. In specific, paternal knowledge and skills involvement positively predicted sons’ perceived paternal support (β = .289, 95% CI [.087, .490]) while paternal time and energy involvement negatively predicted sons’ perceived paternal support (β = − .221, 95% CI [−.442, .000]). None of the indirect effect from paternal involvement to son’s and daughter’s academic engagement was significant (with the exception of one marginally significant indirect effect from paternal knowledge and skills on son’s academic vigor via perceived paternal support).

Mother-Son and Mother-Daughter Dyads

Mother’s parenting practices also predicted son’s and daughter’s learning outcomes differently (see Fig. 4a, b). For maternal parenting, mother’s authoritative parenting only directly and negatively predicted sons’ (not daughters’) academic cynicism (β = − .216, 95% CI [−.401, −.002]). Maternal authoritative parenting also positively predicted perceived maternal support for both sons and daughters (β = .217/.252, 95% CI [.040, .389]/ [.090, .409]).

Indirect effects of maternal parenting and involvement on boys’ and girls’ academic outcomes. A. Mother- Son Dyad Indirect Effect. Maternal authoritative parenting on academic vigor via perceived paternal support .044 90%CI [.005 .107]. Maternal knowledge and skills on academic vigor via perceived paternal support .041 90%CI [.002 .119]. Maternal time and energy on academic vigor via perceived paternal support −.039 90%CI [−.108–.004]. B. Mother- Daughter Dyad. Note. Mediation models for mother-son (3A) and mother-daughter dyads (3B) are shown. Solid lines indicate significant paths (p < .05), and dash lines indicate marginally significant paths (.10 < p < .05). †p < .10 * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001

For maternal involvement, mothers’ knowledge and skills involvement was only marginally significant in predicting daughters’ (not sons’) academic dedication (β = .321, 90% CI [053, .563]). Maternal knowledge and skills involvement also positively predicted perceived maternal support for both sons and daughters (β = .204/.365, 95% CI [.004, .407]/ [.063, .630]). Additionally, maternal time and energy involvement negatively predicted sons’ (not daughters’) perceived maternal support (β = − .194, 95% CI [−.390, −.012]). The overall indirect effects of maternal parenting and involvement on adolescents’ academic engagement were not significant (some were marginally significant for mother-son dyads, Fig. 4).

Discussion

The overall goal of the study was to examine the relations between parenting practices (authoritative, authoritarian, and parental involvement), perceived parental support, and adolescents’ academic burnout and engagement over time among Chinese high school students. In general, authoritative parenting and parental involvement (knowledge and skills) predicted more academic engagement and less academic burnout in adolescents two months later. Moreover, adolescents’ perceived parental support mediated the relations between parenting practices (authoritative parenting and parental involvement) and their academic engagement. Results supported that fathers played an important role in adolescents’ academic engagement (e.g., perceived support from fathers were more strongly linked to adolescents’ engagement than mothers). Fathers and mothers reported different parenting practices and level of involvement (e.g., mothers were more involved than fathers for the same adolescents), and sons and daughters responded differently to their paternal and maternal parenting practices.

Academic Burnout and Engagement

The current study suggested high levels of academic burnout among Chinese adolescents in high school. The percentage reported in this sample (about 46.3% frequently feeling exhausted about schoolwork, and 29.5% frequently experiencing a detached attitude towards learning) were similar to prior studies in China (e.g., 36.8% students experiencing academic exhaustion and cynicism, Zhang et al., 2013), and in the U.S. (e.g., 41.8% high school students feeling stressed, Feld & Shusterman, 2015). On the other hand, a proportion of adolescents in the sample maintained high academic engagement (29.1% frequently feeling vigorous, and 51.2% frequently feeling dedicated while learning). One notable finding was that a subset of adolescents (18.2%, n = 52) experienced academic vigor (engagement) and exhaustion (burnout) at the same time. This finding mirrors a study among 979 Finnish high school students, which showed that 28.0% of students classified as engaged–exhausted were performing well academically in high school (Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, 2014). However, this particular group of engaged-exhausted students may need further support as the research showed that these students were more likely to become disengaged in later years (i.e., college) and display high fear of failure and psychological distress while staying academically committed (Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, 2014). Parents, educators, and mental health providers can teach students study skills (e.g., time management) and emotional regulation strategies in order to prevent academic burnout.

Results identified positive parenting practices that may help to reduce adolescents’ burnout and promote their academic engagement. Consistent with prior research (Baumrind et al., 2010; Li & Gan, 2011; Wilder, 2014), when fathers and mothers applied authoritative parenting and were involved (through knowledge and effective skills), adolescents were less likely to experience exhaustion or have a cynical attitude toward learning. Additionally, when fathers and mothers used authoritative parenting or were more involved in adolescents’ learning (knowledge and skills involvement), adolescents perceived more paternal and maternal support, and in turn, reported more academic vigor or dedication. Consistent with prior research (Soenens et al., 2019), the results suggested that adolescent’s perceived parental support is a crucial factor explaining the links between parenting practices and adolescent’s learning outcomes.

Results extend previous research by demonstrating differential effect of two types of parental involvement for Chinese adolescents (especially boys). While parental knowledge and skills involvement had positive impacts on adolescents’ perceived parental supports, parental time and energy involvement predicted less perceived parental support, especially for boys. This may suggest that, compared with quantity (time spent helping adolescents with homework), quality (skills) of parental involvement is more important. When parents are involved by spending more time in supervising adolescents’ homework but in a less skillful manner (e.g., micro-managing, or criticizing), adolescents (especially boys) may feel that parents are infringing on their autonomy and freedom, resulting in feeling unsupported in the process (Soenens et al., 2019). In contrast, parents who are skillful in their involvement may be able to acknowledge adolescent’s perspectives and adjust parenting strategies, accordingly, resulting in adolescents feeling more supported. Based on transactional perspectives, parent-adolescent relationship is reciprocal, and parents need to adjust their parenting practice based on the adolescents’ needs, which are likely to change over time (Bornstein, 2009). Therefore, parents’ responsiveness in renegotiating their parenting practices is important for the parent-adolescent relationship.

Parenting in Contemporary Chinese Families

Results also highlight cultural consideration in order to understand how authoritative and authoritarian parenting impact Chinese adolescents’ academic engagement and burnout. Somewhat consistent with the cultural relativist perspective, which suggested that one’s cultural background can influence how the child may appraise particular parenting behaviors and to what extent the child is internalizing such behaviors and expectations in their own development (Soenens et al., 2019), mixed results on the role of authoritarian parenting on Chinese adolescents’ academic outcomes were found in this study. While maternal authoritarian parenting marginally predicted more academic exhaustion among sons, paternal authoritarian parenting marginally predicted less academic exhaustion among daughters. Furthermore, authoritarian parenting was not related to perceived parental support. This is in line with the research that the authoritarian parenting does not necessarily result in detrimental effects among Chinese adolescents (Dornbusch et al., 1987; Helwig et al., 2014). In the midst of having high academic expectation in high school in China, adolescent girls may interpret fathers’ rigid parenting strategies within the context of schooling as an expression of care, and hence, may benefit from paternal authoritarian practice. On the other hand, some other studies also showed that a positive individual growth can arise from negative situations, such as family conflict (Lappalainen, 2019). Adolescents may learn how to handle family conflict and become more resilient.

Although research showed that Chinese parents tend to use less physical expression of love and instead use more indirect ways to show supports and warmth (Cheah et al., 2015), parents in the present study reported using more authoritative parenting than authoritarian parenting. This may provide further supports to the existing literature suggesting that authoritative or warm parenting is normative among urban Chinese parents (who are more influenced by fast industrialization and urbanization, and globalization) and is beneficial for adolescents (e.g., Chen & Li, 2012; Zhang et al., 2017).

Gender Differences

Paternal and Maternal Parenting

One unique contribution of this study is collecting data from both mother and father for the same adolescent, which allows comparison of parents’ unique contributions to their adolescent’s learning outcomes. Consistent with prior research (e.g., Hallers-Haalboom et al., 2014), mothers in the current study were also more likely to use authoritative parenting strategies and were more involved. Adolescents also reported they perceived more maternal support than paternal support. However, when data from parent-child dyads were analyzed separately, adolescents’ perceived support from fathers (not mothers) predicted their academic engagement. Additionally, students who reported both fathers and mothers equally involved in their learning, perceived higher paternal and maternal support and also reported higher academic vigor and dedication than students whose parents were not involved. The results echo the idea that both mothers and fathers play important roles for adolescents’ academic outcomes, and they make unique contributions in certain ways (Cabrera, 2020; Jeynes, 2016). Therefore, when studying the influence of parenting on children, it is important to analyze paternal and maternal effects separately, not assuming “sameness” of the two or only focusing on maternal effects.

Additionally, this finding may reflect the gender role in childrearing in China. First, mothers are expected to be the primary caregiver, and fathers to be the bread winner, for the child. Moreover, Chinese fathers are also responsible for maintaining family reputation (Ho, 1987) as also stated in an old Chinese saying, “It is the father’s fault if a child is not well educated (zi bu jiao fu zhi guo).” Chinese fathers are expected and required to help children learn social values, develop appropriate behaviors, and achieve academic success. As academic burnout and engagement in high school closely relate to adolescents’ school and future success (e.g., college admission), hence, the paternal role is important to adolescents’ school performance. Second, 88.4% of mothers in the sample worked full time outside of the home (on average, 8.04 h a day). Maternal labor force participation influences paternal and maternal roles and encourages fathers to be involved in parenting (Lemmon et al., 2018). As a result, fathers’ involvement became necessary in these families. A previous study also found a similar result that while fathers are less involved compared to mothers, the impact of receiving support from fathers may communicate their care and value on child’s school progress, which contribute to better academic engagement in adolescents (Wang & Sheikh-Khalil, 2014).

Youth Gender Differences

The multi-group analysis showed that fathers’ and mothers’ parenting practices influenced sons and daughters in some different ways. Most notably, compared with girls, boys’ burnout was more sensitive to parenting from both parents. When both fathers and mothers used authoritative parenting, boys tended to feel less academically exhausted, but not girls. Maternal authoritarian parenting also marginally predicted more academic exhaustion among boys, but not girls. Adolescent boys may be more susceptible to the influence of parenting, perhaps because the consequence of academic failure is communicated more saliently with boys as parents place higher expectations for boys than girls to bring family honor through their academic attainment (Chui & Wong, 2017).

Fathers and mothers may use different parenting strategies for boys and girls, as the Chinese folk wisdom said, ‘be strict to the sons but caring for the daughters.’ This strict parenting with boys may also explain why parents’ time and energy involvement to be negatively related to perceived parental support among their sons (not daughters) in this study. When parents have to spend more time with their sons due to concerns over poor academic performance, parents may engage in less positive interactions with their sons who, in hence, may feel less supported. For example, parents may set more rule, higher expectation, use more corporal punishment and controlling parenting (Endendijk et al., 2017), and use less empathetic interactions and validation of emotions with boys than with girls (Endendijk et al., 2016; Lambie & Lindberg, 2016; Mandara et al., 2012). Additionally, according to the social role theory, boys are expected to be independent and strong (Eagly et al., 2000), as a result, boys have a stronger need for autonomy than girls. Influenced by stronger desire for autonomy, sons may also interpret parents’ time and energy involvement as intrusion, resulting in less perceived support. Lastly, adolescent boys reported higher academic exhaustion and cynicism than girls in the study. It is important for parents to better support their sons by using more authoritative parenting strategies and higher quality parental involvement (not only with time).

Limitations and Future Directions

The study is not without limitations. First, the data were collected from one high school in Hengyang, China, composed of largely urban parents, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to families with different socio-economical and regional characteristics. Future studies may collect data in different regions, including Chinese rural families. Second, this study only focused on two parenting styles and two types of parental involvement. In the future, researchers may study how other parenting styles (e.g., permissive and disengaged parenting) may impact adolescents’ learning outcomes. Third, data were collected over two months, and we did not control for prior level of burnout and academic engagement. Future studies may want to collect data over a longer period of time and control for prior level of burnout and academic engagement.

Implications

The findings have multiple practical implications. First, alarming number of Chinese high school students experiencing academic burnout suggests the need for teachers and parents to identify and support the students who are burnt out, including the ones who are engaged-exhausted. School psychologists and counselors should provide workshops to high school students about learning strategies and time management and communicate with parents about the importance of effective parenting practices. Second, findings suggest three ways to improve the overall quality of the parent-adolescent relationship: (a) it is important for parents to consider and appreciate adolescents’ needs; (b) parents should use warm parenting to support adolescents’ needs; (c) it is essential for parents to improve the quality of parental involvement (e.g., by improving their communication skills), not only the quantity of parental involvement (e.g., time). Schools can provide parenting workshops on adolescents’ psychological needs, positive parenting skills, and parent-child communication skills, and how to be involved in adolescents’ learning without being intrusive. Lastly, both fathers and mothers are important to adolescents. Therefore, the impact of fathers must be encouraged, perhaps by schools inviting fathers to attend PTA meetings or to be volunteers on school events.

Conclusion

This study extended prior research by investigating the youth’s microsystem (perceived parental support, parenting style) and mesosystem (parental involvement in schools) in relation to their academic burnout and engagement using longitudinal data from multiple informants (Chinese fathers, mothers, and adolescents). Data from both mother and father for the same adolescent allowed comparison of parents’ unique contributions to their sons’ and daughters’ learning outcomes. Results showed that adolescents’ perception of parental support plays an important role in linking parenting practice and adolescent learning. While parental knowledge and skills involvement predicted more perceived parental supports, parental time and energy involvement predicted less perceived parental support, especially for boys. This suggests that quality (skills) of parental involvement may be more important than quantity (time spent helping adolescents with homework) for Chinese high school students. Furthermore, while mothers reported more authoritative parenting and parental involvement than fathers, adolescents’ perceived support from fathers (not mothers) predicted their academic engagement. In addition, compared with girls, boys’ burnout was more sensitive to parenting from both parents. Parents need to adjust parenting in accordance with adolescents’ differing needs and sensitivity in order to show supports. Lastly, parental involvement needs to be understood in the context of adolescent’s developmental needs, such as the autonomy.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

An, L., Liu, C., Zhang, N., Chen, Z., Ren, D., Yuan, F., ... & He, G. (2019). GRIK3 RS490647 is a common genetic variant between personality and subjective well-being in Chinese han population. Emerging Science Journal, 3(2), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.28991/esj-2019-01171

Baumrind, D., Larzelere, R. E., & Owens, E. B. (2010). Effects of preschool parents' power assertive patterns and practices on adolescent development. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(3), 157–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295190903290790.

Bornstein, M. H. (2009). Toward a model of culture↔parent↔child transactions. In A. Sameroff (Ed.), The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other (pp. 139–161). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11877-008.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Ceci, S. J. (1994). Nature-nuture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review, 101(4), 568–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.568.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). Wiley.

Brown, C. S., & Tam, M. (2019). Parenting girls and boys. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (3rd ed., pp. 558–596). Routledge.

Cabrera, N. J. (2020). Father involvement, father-child relationship, and attachment in the early years. Attachment & Human Development, 22(1), 134–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2019.1589070.

Cadime, I., Pinto, A. M., Lima, S., Rego, S., Pereira, J., & Ribeiro, I. (2016). Well-being and academic achievement in secondary school pupils: The unique effects of burnout and engagement. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.10.003.

Chao, R. K. (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development, 65(4), 1111–1119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x.

Cheah, C. S., Li, J., Zhou, N., Yamamoto, Y., & Leung, C. Y. (2015). Understanding Chinese immigrant and European American mothers’ expressions of warmth. Developmental Psychology, 51(12), 1802–1811. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039855.

Chen, S. H., Zhou, Q., Main, A., & Lee, E. H. (2015). Chinese American immigrant parents’ emotional expression in the family: Relations with parents’ cultural orientations and children’s emotion-related regulation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(4), 619–629. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000013.

Chen, X., Fu, R., & Yiu, W. Y. V. (2019). Culture and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (3rd ed., pp. 108–169). Routledge.

Chen, X., & Li, D. (2012). Parental encouragement of initiative-taking and adjustment in Chinese children from rural, urban, and urbanized families. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(6), 927–936. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030708.

Chui, W. H., & Wong, M. Y. (2017). Avoiding disappointment or fulfilling expectation: A study of gender, academic achievement, and family functioning among Hong Kong adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(1), 48–56.

Cummings, E. M., & Warmuth, K. A. (2019). Parenting and attachment. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (3rd ed., pp. 374–400). Routledge.

Dinkelmann, I., & Buff, A. (2016). Children's and parents’ perceptions of parental support and their effects on children's achievement motivation and achievement in mathematics. A longitudinal predictive mediation model. Learning and Individual Differences, 50, 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.06.029.

Dornbusch, S. M., Ritter, P. L., Leiderman, P. H., Roberts, D. F., & Fraleigh, M. J. (1987). The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child development, 58(5), 1244–1257. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130618.

Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., & Diekman, A. H. (2000). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. In T. Eckes & H. M. Trautner (Eds.), The developmental social psychology of gender (pp. 123–174). Erlbaum.

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C., Sucharski, I. L., & Rhoades, L. (2002). Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.565.

Endendijk, J. J., Groeneveld, M. G., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Mesman, J. (2016). Gender-differentiated parenting revisited: Meta-analysis reveals very few differences in parental control of boys and girls. PLoS One, 11(7), e0159193. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159193.

Endendijk, J. J., Groeneveld, M. G., Van der Pol, L. D., Van Berkel, S. R., Hallers-Haalboom, E. T., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Mesman, J. (2017). Gender differences in child aggression: Relations with gender-differentiated parenting and parents’ gender-role stereotypes. Child Development, 88(1), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12589.

Fan, W., & Williams, C. M. (2010). The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self-efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educational Psychology, 30(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410903353302.

Feld, L. D., & Shusterman, A. (2015). Into the pressure cooker: Student stress in college preparatory high schools. Journal of Adolescence, 41, 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.02.003.

Fuligni, A. J. (1998). Authority, autonomy, and parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion: A study of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, Filipino, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 34, 782–792. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.

Gamble, B., & Crouse, D. (2020). Strategies for supporting and building student resilience in Canadian secondary and post-secondary educational institutions. SciMedicine Journal, 2(2), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-0202-4.

Grolnick, W. S., & Slowiaczek, M. L. (1994). Parents' involvement in children's schooling: A multidimensional conceptualization and motivational model. Child Development, 65(1), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00747.x.

Hallers-Haalboom, E. T., Mesman, J., Groeneveld, M. G., Endendijk, J. J., Van Berkel, S. R., Van der Pol, L. D., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2014). Mothers, fathers, sons, and daughters: Parental sensitivity in families with two children. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036004.

Helwig, C. C., To, S, Wang, Q., Liu, C., & Yang, S. (2014). Judgments and reasoning about parental discipline involving induction and psychological control in China and Canada. Child Development, 85(3), 1150–1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12183.

Hill, N. E., & Taylor, L. C. (2004). Parental school involvement and children's academic achievement: Pragmatics and issues. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(4), 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00298.x.

Ho, D. Y. F. (1987). Fatherhood in Chinese culture. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The father’s role: Cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 227–245). Erbaum.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (1995). Parental involvement in children's education: Why does it make a difference? Teachers College Record, 97(2), 310–331.

Hu, Q., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). The factorial validity of the Maslach burnout inventory–student survey in China. Psychological Reports, 105(2), 394–408. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.105.2.394-408.

Jeynes, W. H. (2016). Meta-analysis on the roles of fathers in parenting: Are they unique? Marriage & Family Review, 52(7), 665–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2016.1157121.

Lambie, J. A., & Lindberg, A. (2016). The role of maternal emotional validation and invalidation on children's emotional awareness. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 62(2), 129–157. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.62.2.0129.

Lappalainen, P. H. (2019). Conflicts as triggers of personal growth: Post-traumatic growth in the organizational setup. SciMedicine Journal, 1(3), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2019-0103-2.

Lay-Khim, G., & Bit-Lian, Y. (2019). Simulated patients’ experience towards simulated patient-based simulation session: A qualitative study. SciMedicine Journal, 1(2), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2019-0102-3.

Lemmon, M., Patterson, S. E., & Martin, M. A. (2018). Mothers’ time and relationship with their adolescent children: The intersecting influence of family structure and maternal labor force participation. Journal of Family Issues, 39(9), 2709–2731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18756929.

Lewis, A. J., Kremer, P., Douglas, K., Toumborou, J. W., Hameed, M. A., Patton, G. C., & Williams, J. (2015). Gender differences in adolescent depression: Differential female susceptibility to stressors affecting family functioning. Australian Journal of Psychology, 67(3), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12086.

Li, M., & Gan, Y. (2011). Relationship between academic burnout and parental styles in senior high school students. Chinese Journal of School Health, 32(1), 36–37.

Li, R., Zhu, W., Liu, H., & Yao, M. (2018). How parental educational expectation influence student academic burnout: The mediating role of educational involvement and moderating role of family functioning. Psychological Development and Education, 34(4), 489–496.

Li, X., & Huang, R. (2010). A revise of the UWES-S of Chinese college samples. Psychological Research, 3(1), 84–88.

Lowe, K., & Dotterer, A. M. (2013). Parental monitoring, parental warmth, and minority youths’ academic outcomes: Exploring the integrative model of parenting. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(9), 1413–1425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9934-4.

Mandara, J., Murray, C. B., Telesford, J. M., Varner, F. A., & Richman, S. B. (2012). Observed gender differences in African American mother-child relationships and child behavior. Family Relations, 61(1), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00688.x.

Mascaro, J. S., Rentscher, K. E., Hackett, P. D., Mehl, M. R., & Rilling, J. K. (2017). Child gender influences paternal behavior, language, and brain function. Behavioral Neuroscience, 131(3), 262–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/bne0000199.

Milevsky, A., Schlechter, M., Netter, S., & Keehn, D. (2007). Maternal and paternal parenting styles in adolescents: Associations with self-esteem, depression and life-satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9066-5.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2017). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables, user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Myers, T. A. (2011). Goodbye, listwise deletion: Presenting hot deck imputation as an easy and effective tool for handling missing data. Communication Methods and Measures, 5, 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2011.624490.

Ng, F. F. Y., & Wang, Q. (2019). Asian and Asian American parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (3rd ed., pp. 108–169). Routledge.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Nielson, M. G., & Day, R. D. (2016). The role of parental warmth and hostility on adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward multiple targets. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(3), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000157.

Piko, B. F., & Balázs, M. Á. (2012). Control or involvement? Relationship between authoritative parenting style and adolescent depressive symptomatology. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 21(3), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-012-0246-0.

Ruholt, R. E., Gore, J., & Dukes, K. (2015). Is parental support or parental involvement more important for adolescents? Undergraduate Journal of Psychology, 28(1), 1–8.

Salmela-Aro, K., & Upadyaya, K. (2014). Developmental trajectories of school burnout: Evidence from two longitudinal studies. Learning and Individual Differences, 36, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.10.016.

Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003.

Shih, S. S. (2015). An investigation into academic burnout among Taiwanese adolescents from the self-determination theory perspective. Social Psychology of Education, 18(1), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-013-9214-x.

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children's behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233.

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Beyers, W. (2019). Parenting adolescents. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (3rd ed., pp. 111–167). Routledge.

Tuominen-Soini, H., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2014). Schoolwork engagement and burnout among Finnish high school students and young adults: Profiles, progressions, and educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 50(3), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033898.

Walker, J. M., Wilkins, A. S., Dallaire, J. R., Sandler, H. M., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. (2005). Parental involvement: Model revision through scale development. The Elementary School Journal, 106(2), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1086/499193.

Wang, M. T., & Sheikh-Khalil, S. (2014). Does parental involvement matter for student achievement and mental health in high school? Child Development, 85(2), 610–625.

Way, N., Okazaki, S., Zhao, J., Kim, J. J., Chen, X., Yoshikawa, H., Jia, Y., & Deng, H. (2013). Social and emotional parenting: Mothering in a changing Chinese society. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031204.

Wilder, S. (2014). Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: a meta-synthesis. Educational Review, 66(3), 377–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.780009.

Xie, S., & Li, H. (2018). Does tiger parenting work in contemporary China? Exploring the relationships between parenting profiles and preschoolers’ school readiness in a Chinese context. Early Child Development and Care, 188(12), 1826–1842. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1521806.

Zhang, W., Wei, X., Ji, L., Chen, L., & Deater-Deckard, K. (2017). Reconsidering parenting in Chinese culture: Subtypes, stability, and change of maternal parenting style during early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(5), 1117–1136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0664-x.

Zhang, X., Klassen, R. M., & Wang, Y. (2013). Academic burnout and motivation of Chinese secondary students. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 3(2), 134–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036810500130539.

Zhou, Y., Liang, B., Cai, Y., & Chen, P. (2010). Chinese revision of Buri’s parental authority questionnaire. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18(1), 8–10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Q., Cheong, Y., Wang, C. et al. The impact of maternal and paternal parenting styles and parental involvement on Chinese adolescents’ academic engagement and burnout. Curr Psychol 42, 2827–2840 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01611-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01611-z