Abstract

The associations between attachment relationships, negative automatic thoughts, and psychological problems are theoretically supported and well-entrenched in the literature. Based on the integration of the attachment theory and the cognitive theory, the current study investigated: (a) the mediation effect of negative automatic thoughts in the linkages between attachment relationships (maternal, paternal, and peer attachment) and psychological problems (depressive and anxiety symptoms); and (b) the moderating role of adolescent’s gender in the mediation model. The data in this cross sectional study were collected from 936 Pakistani late adolescents (mean age = 17.79 years, SD = .69) studied in Rawalpindi district colleges, through multi-stage cluster sampling. Participants completed a set of questionnaires including Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment-Urdu, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale and Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire. The models were tested through structural equation modelling. Results indicated that quality of maternal and peer attachments were indirectly linked with depressive and anxiety symptoms via negative automatic thoughts, paternal attachment was directly and indirectly associated with depressive symptoms, while parental attachment was indirectly related to anxiety symptoms. Additionally, the moderated mediation analysis showed that for females, quality of maternal, paternal, and peer attachment showed indirect association with depressive and anxiety symptoms. For males, only paternal and peer attachment had significant association with depressive and anxiety symptoms through negative automatic thoughts. The current study enhances our understanding of the distinct role of attachment security with mother, father and peers on the differential developmental outcomes of male and female adolescents. Implications are further discussed in the article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, almost 20% of adolescents are suffering from psychological problems (World Health Organization [WHO] 2017). Depressive and anxiety symptoms are the most prevalent psychological problems among adolescents. These symptoms are likely to be low and stable in early or middle adolescents, but increase among late adolescents and emerging adults (Hankin et al. 2015; Nelemans et al. 2013). The situation is more problematic in Asian countries like Pakistan. Past studies have also reported a high prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among late adolescents in Asian countries (Jin et al. 2014; Khalid 2014; Waghachavare et al. 2016). The plausible reasons for such a high prevalence include lack of awareness about these psychological problems, and the limited psychological and psychiatric services for adolescents (WHO 2017). Depressive symptoms among adolescents in Pakistan can be characterized by feelings of sadness, fear of making mistakes, lack of concentration, boredom, lack or excessive sleep, physical fatigue, nervousness, and muscle pain (Saleem et al. 2014). On the other hand, anxiety symptoms are characterized by a fear of negative evaluation of others, worries, and concerns (Ahmad and Bano 2013). These problems affect late adolescent’s academic and psychosocial lives. Additionally, depressive and anxiety symptoms are one of the major causes of disability among youngsters and if remain unattended during this stage, may increase the chances of developing more severe psychological disorders in later stages (Clayborne et al. 2019; Nelemans et al. 2013). Therefore, understanding the factors contributing to these psychological problems is imperative for the designing of better intervention and prevention plans for late adolescents.

Previous studies (e.g., Dhillon and Kanwar 2015; Omidvar et al. 2015) have reported that most of adolescents’ emotional and psycho-social problems arise from the quality of their relationships with significant others. One of the vital aspects of relationships is attachment. According to the attachment theory, attachment is an enduring affectional connection or bond between a child and his/her primary caregiver (Bowlby 1969). Attachment develops during early years of life but may influence later adaptation and psychological functioning (Fraley 2019). During adolescence quality of maternal, paternal and peer attachment relationships plays a pivotal role in the developmental outcomes of youngsters (Allen and Tan 2016; Armsden et al. 1990; Yeh et al. 2014).

Attachment Quality and Psychological Problems

According to Armsden and Greenberg (1987) quality of maternal, paternal and peer attachment relationships are the perception of secure and insecure affective and cognitive dimensions of adolescent’s relationship with their mother, father and peers. Late adolescence represents a significant period of simultaneous and rapid development in various physical, social and cognitive aspects that may decrease the dependency on the parents. The strong need for mastering and exploration of new environment at this stage promotes the formation of relationship outside family such as with friends. Peers during this phase provide high level of instrumental support, companionship and facilitate exploration of new environment, hence strengthening peer attachment relationship (Ainsworth, 1989). These developmental changes lead to the possible reconceptualization of the attachment relationships. Attachment researchers pointed out that attachment relationship is more a dyad-specific; therefore, attachment with multiple attachment figures such as mother, father and peer may be different from each other (Howes and Spieker 2016). For instances, mothers are generally considered a safe haven, encouraging caregiver and source of comfort to the child; while, fathers are viewed as a figure who facilitates the child’s exploration and autonomy (Bowlby 1969; Dumont and Paquette 2013). Ruhl et al. (2015) accentuated this notion from the adolescent’s perspective and stated that father promotes independence in adolescents by providing support, companionship and warm attitude, whereas, mother’s approval, acceptance and abridged criticism is a source of care. Furthermore, adolescents expend most of their time in school or college and their interaction with peers increase; therefore, peers may serve the function of safe haven and proximity (Allen and Tan 2016; Bowlby 1973; Furman 2001). This viewpoint is also supported by Rosenthal and Kobak (2010), reported that peer attachment in adolescence was related to affiliation and support-seeking preferences. These differential functions of attachment with the mother, father and peers highlight the need to separately examine the contribution of each type of attachment (i.e., maternal-adolescent, paternal-adolescent and peer-adolescent) to depressive and anxiety symptoms.

There has been mixed empirical evidence on the links of the quality of maternal, paternal, and peer attachment relationships with adolescents’ symptoms of depression and anxiety. One of the pioneering studies on the association between attachment and internalizing symptoms in adolescents was conducted in 1990’s. Accordingly, it was found that as compared to peer attachment, less secure attachment to parents was associated with the history of suicidal ideation, maladaptive attributional styles and separation anxiety (Armsden et al. 1990). Additionally, they also found that secure parental attachment was negatively related to severity of depression. On the other hand, Tambelli et al. (2012) found that alienation from parents and low levels of trust in peers were significantly associated with internalizing problems. In addition, Holt et al. (2018) examined the impact of change in quality of parent-peer relationship on the academic, emotional and social functioning during transition from high school to college. Authors highlighted that maternal and peer attachments significantly predict the depression level among emerging adult in the transition to college life. Besides, Dhillon and Kanwar (2015) observed that secure paternal and maternal attachment had negative associations with depression and anxiety among early adolescents. Likewise, Yeh et al. (2014) found that problems in peer relationships and alienation from mother and father trigger the development of depressive and anxiety symptoms among high school students. Taken together, most studies showed that maternal, paternal and peer attachment relationships distinctively contribute to psychological problems. However, most of these studies investigated parental attachment as a unitary construct and were unable to explain the mechanism through which each type of attachment uniquely contributes to the symptoms of depression and anxiety among late adolescents. Other important limitations will be addressed further in this article.

Negative Automatic Thoughts and Psychological Problems

Beck (1967) characterized negative automatic thoughts as the negative thinking patterns about the self, others, and the world. Individuals with negative automatic thoughts perceive themselves as a failure, think that their future is bleak, and the world or environment prevents their satisfaction. The underlying schemata and negative automatic thoughts affect one’s way of thinking and interpretation of a situation, which in turn, results in maladaptive coping strategies (i.e., negative and self-defeating thoughts, emotional numbness, self-blame, intrusive thoughts, helplessness, rumination, and escape) and behaviors (Beck 1963, 1967). These thoughts are emotionally distressing, interfere with individual functionality, and distort reality. Beck’s cognitive model posits that most of the psychological problems arise from the interpretation of experiences in a negative and stubborn way (Beck and Haigh 2014).

Negative thoughts are related to specific emotions depending upon their meaning and content. For instance, thoughts indicative of depressive symptoms include negative views about the self, the world and the future whereas, for anxiety, these thoughts reflect themes of risk and underestimation of coping. Depression and anxiety mostly show considerable sequence in comorbidity (Garber and Weersing 2011). Therefore, depression and anxiety may have shared cognitive vulnerabilities. To inspect this notion, Brown et al. (2014) examined association of cognitive content specificity with anxiety and depression across various developmental stages for instance, childhood, adolescence and early adulthood. Results showed that physical content is more related to anxiety while social and mental aspect were associated with both depression and anxiety. Likewise, Ho et al. (2018) found that positive attentional bias, less level of negative attentional bias, and the dimension of anxiety sensitivity (i.e., physical concerns) were related to the development of depression and anxiety among adolescents. However, past studies have reported associations between automatic thoughts and symptoms of depression and anxiety (Beck and Haigh 2014; Hjmedal et al. 2013).

Attachment Quality and Negative Automatic Thoughts

The quality of attachment with significant others brings about cognitive and affective resources which help an individual to survive during turmoil and stressful life events. Bowlby (1973) termed these resources as internal working models (IWMs), which are developed during early years of life through experiences and interactions with the attachment figure (Bowlby 1982). A child who is securely attached with significant others formed healthy relationships and positive or adaptive IWMs of the self and others; whereas those who are insecurely attached may display poor emotion regulation and difficulty in adjustment, and develop maladaptive internal representations about the self and others (Clear and Zimmer-Gembeck 2015; Margolese et al. 2005). Past studies have reported a positive association between insecure attachment relationships and negative cognitions. For instance, Sharpa et al. (2016) have investigated the link between attachment, emotion dysregulations and social cognition among 12 to 17 years adolescents. The authors found that secure attachment with significant relationships decrease emotion dysregulations and negative social cognitions. Nevertheless, to date, little evidence has been found associating maternal, paternal, and peer attachment with negative automatic thoughts among late adolescents and in Non-Western society.

Mediating Role of Negative Automatic Thoughts in the Link between Attachment Relationships and Psychological Problems

In order to understand the underlying mechanism in the development of psychological problems among youngsters, attachment and cognitive theories were used. The maladaptive IWMs of self and others develop as a result of interaction with unsupportive and unreliable caregiver, act as cognitive filters. These filters guide the interpretation of current experiences and formulate the ongoing expectations of the self and others (Bowlby 1982). The maladaptive IWMs emphasized by the attachment theory can be explained through Beck’s concept of negative automatic thoughts about the self, the world and the future. Such negative thinking results in the development of psychological problems. In support to this theoretical integration, an earlier research examined the attachment working models related to mother, father, peer and romantic partner as precursors to depression during adolescence (Margolese et al. 2005). This study noted that adolescents who had more negative models of the self and others, specifically in relation to their mothers, or those who had more negative internal models about the self but positive models about the romantic partner exhibited high level of depressive symptoms, particularly in adolescent’s girls. The authors further recommended the integration of the attachment and cognitive theories in order to understand vulnerability to psychological problems in adolescents, specifically, the role of negative automatic thoughts. The present study thus employed integration of attachment and cognitive theories to explore the mediating effect of negative automatic thoughts in the association between attachment relationships (maternal, paternal and peer attachment) and psychological problems (symptoms of depression and anxiety) among late adolescents.

Most of the past studies that examined the mediating effect of cognitive vulnerability among attachment and psychological problems, have either studied parents as a unitary variable, or examined only depression, or internalizing/ emotional problems without stating separate analysis for depressive and anxiety symptoms (Love and Murdock 2012; Roelofs et al. 2013). Few studies have simultaneous tested the associations among attachment, cognitive vulnerability and symptoms of depression and anxiety. One such old study was done by Safford et al. (2004), which examined the association between attachment styles, negative cognitive style, and symptomology of depression and anxiety among 167 college students. The authors found that negative cognitive style did not mediate the link between attachment styles and symptoms of depression and anxiety. On the other hand, Lee and Hankin (2009) stated that dysfunctional attitudes and low self-esteem mediated the association of attachment styles with both depression and anxiety. These studies explain findings in terms of the link between attachment styles and psychological problems but did not provide information about the unique role of perceived quality of attachment relationships such as mother, father and peers in the development and prediction of cognitive vulnerability and psychological problems among late adolescents. However, the findings of these studies provided a foundation for examining the integration of attachment and cognitive theories.

Moderating Role of Gender

Developmental theorists have documented differential emotional, physical and psychosocial development of males and females during adolescence. According to Wise (2014), the psychosocial development of females is likely to be based on bonding, connectedness, and intimate relationships; whereas, that of males is based on detachment and separation. Consequently, perceived quality of attachment relationships to parents and peers and attachment-related outcomes are different in males and females. Previous studies indicated that, as compared to male adolescents, females scored higher on depressive and anxiety symptoms, which may be due to the differential rearing of males and females (Hankin et al. 2015; Park et al. 2016).

Existing literature has highlighted the distinction between quality of mother, father and peer attachment across gender and its impact on adolescent’s developmental outcome, however, findings are equivocal. For instances, Omidvar et al. (2015) revealed that problems in maternal, paternal and peer attachment increase the probability of development of depressive symptoms in both girls and boys. Likewise, Breinholst et al. (2019) found non-significant effect of gender in relation between insecure maternal and paternal attachment with anxiety among children. Contrary, Van Eijck et al. (2012) observed that quality of paternal attachment predicted general anxiety disorder (GAD) in adolescents, particularly among males. Moreover, Park et al. (2016) found that the presence of a rejecting maternal attitude decreased self-esteem in both male and female adolescents and increased negative automatic thoughts among females only. Laghi et al. (2016) also observed gender differences in the association between peer and parent attachment and negative thoughts. The authors noted that girls were more pessimistic and scored higher on negative past experiences and alienation from parents and peers. Besides, Ho et al. (2018) reported that girls scored higher on the negative thinking and symptoms of anxiety and depression compared with boys. Contrary to this, Alsaleh et al. (2016) did not find a significant moderating effect of gender on the relationship between negative thoughts and psychological problems. One possible reason for these inconsistent findings would be different measures were used to examine quality of attachment, negative thoughts and psychological problems. In summary, inconsistent findings highlighted a need for more studies investigating the link between attachment and psychological problems among adolescents by taking gender into account.

Pakistani Context

Pakistan is an Islamic South Asian country having 95–98% muslim population. It is multicultural and multi-ethnic country. It ranked sixth among the most populous country in the world, in which almost 64% of the population are below 30 years old (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics [PBS] 2017). At this time, Pakistani society is facing many political, economic and social strains, which have led to greater vulnerability to stress among its population. Ahmed et al. (2016) conducted a review of literature on the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms reported in different localities of Pakistan during the time period of ten years. The authors revealed that 22% to 60% of the population in Pakistan have been suffering from psychological problems. Today, Pakistan has a younger population than at any other time in its history, but there is no specific plan in place to ensure the healthy development of its youth. It can also be added that the lack of opportunities and resources available to Pakistani youth only serves to increase their levels of stress (Soomro and Tan Shukui 2015). Depressive and anxiety symptoms are considered as one of the leading causes of suicide in Pakistan (Naveed et al. 2017). In spite of this, Pakistan spends remarkably little on mental health concerns. There are only four child and adolescent psychiatrists available for rehabilitation and treatment of young individuals (Younus 2017). Moreover, there is lack of research on the factors contributing to the psychological problems of Pakistani adolescents.

Generally, the patriarchal system is practiced in Pakistan, where father represents the head of the family and makes most of the decisions, while the mother mainly stays at home to look after the children. Most of the families are extended in nature, but due to socio-economic issues, there has been a growing trend towards a nuclear family comprising of two parents and one or more children (Baig et al. 2014). These social changes may directly or indirectly affect the bond between people and their psychological wellbeing. Mesman et al. (2016) have recommended that as a result of socioeconomic problems in the developing countries, parents might be not very sensitive to their children, thus, insecure attachment relationships’ occurrence may be higher in developing countries (Spruit et al. 2020). Pakistan is also one of the developing countries where economic issues have been elevated therefore, problems in the attachment relationships might be observed. Additionally, previous studies have reported that in low-income countries like Pakistan, low level education, negative life events, female gender, parent-child relationship problems, and number of close friends are the most significant contributing factors to the psychological problems of youngsters (Amaltinga and Mbinta 2020; Rao et al. 2015).

In Pakistan, research on the psychosocial development of youngsters and its impact on their psychological health are still at infancy stage. Consequently, it is challenging to say whether results of the current study would be similar to the literature in western society, and attachment and cognitive theory would be applicable on Pakistani adolescents. To understand variations between Western and non-Western societies a recent study has examined the association between primary attachment, secondary attachment, coping strategies, and mental health among Pakistani and Scottish adolescents, reported few differences among two countries (Imran et al. 2020). For instances, Scottish adolescents identify friends and Pakistani sample identify siblings as secondary attachment. Additionally, associations among variables obtained only for Pakistani sample included link between emotion-focused coping with psychological well-being and psychological distress was moderated by secondary attachment, and task-focused coping significantly mediate the association between primary attachment and psychological distress. Authors further reported that primary attachment significantly predicted psychological wellbeing through adaptive coping strategies in both samples. This indicates that the attachment theory’s major proposition which is secure attachment with primary care giver forms adaptive internal resources which in turn enhance mental health, is universally applicable. Imran et al. (2020) study underscored the role of interpersonal relationships in the development of psychological problems in Non-western countries. However, this study did not provide evidence about unique function of various attachment relationships’ quality in predicting mental health problems among late adolescents in Pakistan.

Moreover, despite of modernization, traditional gender roles are still generally followed in the Pakistani society and differences between the development of adolescent males and females are pronounced (Irfan 2016). This distinction between roles suggests that females are more attached to their close relations and receive support, love, and care from their family and friends; while males are expected to be dominant and independent. Males are also expected to start earning by the time they reach late adolescence, which leads to greater family pressures. Moreover, differences have also been observed in the perception of attachment with significant others, cognitive vulnerability, and prevalence of psychological problems among male and female adolescents (Khalid 2014; Naz and Kausar 2013). With these considerations in mind, understanding the moderating effect of adolescent gender on the connections between quality of attachment relationships, negative automatic thoughts, and psychological problems among late adolescents of Pakistan could have important implications for intervention and prevention strategies.

The Current Study

Regardless of the argument that parents continue to be a primary attachment figure until late adolescence, the inconsistent research findings makes it hard to draw the conclusion on the relative contributions of paternal and maternal attachment quality to adolescent’s psychological problems. In addition to paternal and maternal attachment, peer attachment has become a source of emotional support during adolescence. Despite the significant roles of paternal, maternal, and peer attachment, limited number of studies are available that simultaneously examined the link of these attachment relationships with psychological problems among late adolescents. Moreover, depressive and anxiety symptoms are commonly unnoticed during adolescence because irritability, mood fluctuations, worry and fear are the normal features of this developmental stage (Siegel and Dickstein 2012; Thapar et al. 2012). In Pakistan most of the mental health symptoms overlap with physical complaints, which could be the reason that these problems remain unattended (Irfan 2013). This can be articulated in the lack of research on the psychological well-being of young population of this country. Furthermore, most of the previous studies have investigated depression and anxiety under one category such as internalizing problems because these problems co-occur and overlap in terms of symptoms, sequel and causes (Roelofs et al. 2013; Tambelli et al. 2012). However, literature suggested examining these two problems together in one study but as a separate mental health problem to get information and clarification on the differences and similarities of the etiology of these psychological problems (Cummings et al. 2013). Additionally, the mechanism through which attachment quality is associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms through negative automatic thoughts needs to be explored.

During adolescence prominent differences between male and female exists due to variances in up bringing, societal norms, parent’s attitude, and puberty. Therefore, it can be expected that association between attachment quality, negative automatic thoughts and psychological problems can be different among male and female adolescents. Furthermore, a number of studies have been conducted in Western and high-income countries to investigate certain issues related to the psychological health of adolescents. Research in Asia, however, which mainly focused on low or middle-income countries like Pakistan, remains somewhat scarce and with noteworthy methodological or conceptual limitations. Therefore, it is deem significant to investigate the contributing factors to depressive and anxiety symptoms embedded in interpersonal relationships, to develop better health services and programs for youngsters in Pakistan.

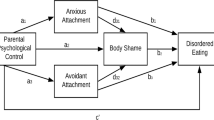

Furthermore, to assess the influence of perceived quality of maternal, paternal and peer attachment relationships on adolescents’ depressive and anxiety symptoms more accurately, it is vital to control for the effect of age and different academic subjects. The current study added these two control variables because symptoms of depression and anxiety increase with age and adolescents studying more difficult subjects may have more psychological problems because of the social pressure to get good grades (Wani et al. 2016). However, to fill the gaps in the literature, we investigated the association between the quality of attachment relationships and psychological problems among late adolescents in Pakistan, as well as the role of negative automatic thoughts as mediator and gender as moderator, respectively. The conceptual model given below explained links between the variables (Fig. 1).

Based on the literature review, the following hypotheses are proposed: Hypothesis 1: Negative automatic thoughts will mediate the link between quality of attachment relationships (mother, father and peer) and psychological problems (depressive and anxiety symptoms), after controlling for age and subject (details of academic subjects are given in methodology section). Specifically, insecure attachment to mother, father, and/or peer will be associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms through negative automatic thoughts. Hypothesis 2: Gender will moderate the association between quality of attachment relationships, negative automatic thoughts and psychological problems, after controlling for age and subject. Specifically, the strength of the associations between insecure attachment relationships (maternal, paternal and peer), negative automatic thoughts and levels of symptoms of depression and anxiety will be stronger in females than in males.

Method

Participants

The data in the present cross-sectional study were collected from six government colleges in the Rawalpindi district of Pakistan. Multi-stage cluster technique was used to identify the required number of respondents. The sampling process was completed in three phases, namely, tehsil (subdivision of district), college, and class levels. Each phase involved a series of steps to ensure that the sample was selected randomly. In the first step, three out of the seven tehsils in the Rawalpindi district were randomly selected. In Rawalpindi district, most of the government colleges and higher secondary levels are single-gendered. Thus, in the second step, two single-gender colleges (one for males and one for females) were randomly selected from each chosen tehsil. The late adolescents in Pakistan generally study in classes XI (Grade 11th) and XII (Grade 12th) in colleges. Consequently, in the last step, classes were randomly selected from XI and XII year levels. There are three major subject groups in these year levels including arts group (F.A), science group (F.Sc) and computer sciences (ICS). One class from each subject group was randomly selected. All students from the selected classes were invited to participate in the study.

Online a-priori calculator was used to calculate the sample size for the present study. Initially a total of 967 students were approached; however, only 936 students completed the survey. The response rate in this study was almost 96%. The sample consisted of 423 (45.2%) males and 513 (54.8%) females. Participants were 17- (36.6%), 18- (47.4%), and 19- (16.0%) year-olds, and had a mean age of 17.79 (SD = .69). Additionally, most of the participants were single (98.6%), Muslims (99.7%), with married parents (93.3%), indicating that most of them came from intact families. They also had middle-aged parents, wherein the mean paternal age was 49.3 years (SD = 6.8), while the mean maternal age was 42.76 years (SD = 5.8). In addition, most of the fathers had secondary education (35.5%), some had primary (18.4%) or no formal education (18.5%) while others either had higher secondary education (10.4%), master degree (6.6%), bachelor (4.1%), PhD (.6%) or did diploma (3.6). The average monthly income of most of the fathers was around 31,318.09 PKR or 198.49 USD which is equivalent to the average monthly income of Pakistani citizen (PBS 2017) such as, 32,000 PKR (USD = 201.18). Most of the mothers had primary (24.6%) or secondary (22.2%) education, and were housewives (92%). Only 7.1% had a mother who was employed with an average monthly income of 1232.35 PKR (USD = 7.81). Participants reported spending most of their time with their biological parents (91.6%).

Procedure

Prior to data collection, permissions were acquired from the Education Directorate and principals of the selected colleges. The study protocols were approved by the ethics committee of Universiti Putra Malaysia (Jawatankuasa Etika Penyelidikan Universiti Melibatkan Manusia), letter number is UPM/TNCPI/RMC/JKEUPM/1.4.18.2 (JKEUPM). The survey was administered in groups during class hours from December 2017 to January 2018. Oral and written informed consents were acquired from all the participants who were at least 18 years and from the parents of those who were aged 17 and younger. Participants were informed about their right to discontinue at any time. The participants took 30–45 min to complete the booklet containing self-reported measures on demographic information, attachment with mother, father and peers, negative automatic thoughts, and psychological problems.

Instruments

Parent and Peer Attachment

Adolescents’ levels of attachment security with their father, mother and peers were assessed through the Urdu-translated Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA-Urdu; Zafar 2009). It is a five-point scale (1 = never true to 5 = always true) originally developed by Armsden and Greenberg (1987). It contains 25 items in each of the three subscales: maternal scale (My mother respects my feelings), paternal scale (I feel my father does a good job as my father), peer attachment (When we discuss things, my friends care about my point of view). The negatively worded scores were reverse coded and then aggregated into a single score. High scores on the IPPA-Urdu scale indicate secure attachment; whereas, low scores suggest insecure attachment. Armsden and Greenberg (1987) have reported convergent and discriminant validity and good internal consistencies of maternal (.87), paternal (.89) and peer (.92) attachment scales. Likewise, previous studies reported good internal consistency of IPPA-Urdu scale (Safdar and Zahrah 2016; Zafar 2009). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha for maternal attachment scale was .84, paternal attachment scale was .86 and peer attachment scale was .89, showed good levels of internal reliability.

Depressive and Anxiety Symptomatology

The prevailing symptoms of depression and anxiety among late adolescents were measured with the Urdu-translated Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-Urdu; Zafar and Khalily 2014), which was originally developed by Lovibond and Lovibond (1995). DASS-Urdu has 42 items distributed into three subscales with 14 items each. Only depressive (I felt that I had lost interest in just about everything) and anxiety (I perspire noticeably in the absence of high temperatures or physical exertion) symptoms subscales were used in this study. The items were ranked from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much), reflecting the range of severity of symptoms from minimum to extreme. Higher scores on the subscale indicate more self-reported depressive and anxiety symptomatology. Lovibond and Lovibond (1995) reported good construct validity and reliabilities of depression (.91) and anxiety (.81) scale. The DASS-Urdu scale has been shown to be reliable and valid when used with a non-clinical adolescent sample (Zafar and Khalily 2014, 2015). In the present study, the internal reliabilities were likewise good (Cronbach’s alpha = .83 for depressive symptoms, Cronbach’s alpha = .80 anxiety symptoms).

Negative Automatic Thoughts

Adolescents rated their negative thoughts using the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ-Urdu; Hashmi 2012). This scale was originally developed by Hollon and Kendall (1980). It encompasses 30 negative self-statements (I am so disappointed in myself) based on a five-point Likert-type measure (1 = not at all to 5 = all the time). The participants responded to each statement according to the frequency of each thought in the previous week. High scores on the scale indicate greater levels of negative thinking. The results of the pilot study (N = 98) showed that the ATQ-Urdu was easily comprehended by late adolescents in Pakistan (Irfan and Zulkefly 2020). Hollon and Kendall (1980) reported that original english version of ATQ had excellent split half (.97) and cronbach’s alpha (.96) reliabilities. Similarly, the internal consistency of the ATQ-Urdu has been reported to be excellent (Hashmi 2012). In this study, the ATQ-Urdu demonstrated excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .93).

Data Analysis Plan

Two softwares, namely, the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS-23) and Analysis of Moment Structures 23.0 (AMOS-23) version were used for data screening and analysis. In the first step of data screening, missing values were identified through Little’s MCAR test, which showed that omissions in the present study data were completely random (χ2 = 5253.3, df = 5204, p > 0.05). The analysis showed that approximately 57% of the respondents completed the full questionnaire booklet. The remaining 43% did not respond to the items on demographics and/or research constructs. The analysis showed that none of the respondent had a missing value higher than 4% of the study variables. Therefore, imputation was performed through expectancy maximization (EM). However, imputation was done only with the items on the research constructs before summing the scores. Moreover, normality was measured by means of univariate and multivariate skewness (SK < 3) and kurtosis (KU < 8–10; Kline 2005). Accordingly, the data did not violate the assumptions of normality. Potential multivariate outliers were checked through Mahalanobis distance squared (MD2) method (p1 and p2 < 0.001). Subsequently, 18 cases were detected as outliers and were deleted. The statistical analyses performed to detect comparisons between males and females on all research variables included means, standard deviations, and correlations. The strength of the relationship was determined according to Cohen’s recommendations, which stated that the values between .1–.3 are to be interpreted as small, .3–.5 are medium, and greater than .5 is large (Cohen 1988).

To test the hypotheses, structural equation modelling (SEM) was employed. For the model estimation, the maximum likelihood method was used. Given the recommended three-index presentation strategy by Hair et al. (2010), model fit was examined with root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and normed chi-square. The model could be considered as good fitted if RMSEA is less than .08, TLI is greater than .90 and normed chi-square is less than 5 (Brown 2006; Hair et al. 2010). Bootstrapping was used to establish the mediation effect of negative automatic thoughts in the association between quality of attachment relationships and psychological problems, in which 5000 resampling was performed to produce biased-corrected (BC) 95% confidence intervals for the significant effects. Moreover, the criteria to determine whether negative automatic thoughts partially or fully mediate the link between attachment quality and psychological problems was based on the significance of the direct effect and standardized indirect effect (SIE). For instance, negative automatic thoughts was considered to partially mediate the link between quality of attachment relationships and psychological problems if direct effect and SIE were significant. Whereas, if SIE was significant but direct path was not significant, then the path is said to be fully mediated. We further examined whether the mediation model would be moderated by gender through bootstrapping and multi-group analyses. For multi-group tests, chi-square differences between the invariant and variant models were assessed. The diagnostic test was used to examine path wise moderation, which was interpreted using the recommendation by Hair et al. (2010) that if the path coefficient for one group is positive and the other is negative or if one is significant and the other is non-significant, then than the path is considered to be moderated. Additionally, for the bootstrapping test, Hayes’ (2015) criteria were used to test the significant direct and indirect effects and indexes of the moderated mediation models.

Results

Descriptive and Correlation Analyses

The means and standard deviations for and correlations between maternal, paternal and peer attachment, negative automatic thoughts, and depressive and anxiety symptoms are reported separately for males and females in Table 1. Accordingly, all the variables were significantly correlated with each other for both genders. Further, attachment relationship was negatively correlated with negative automatic thoughts and psychological problems. In contrast, negative automatic thoughts was positively correlated with psychological problems. The magnitudes of the correlations between the variables were medium or large for both males and females, except for the association of maternal attachment with depressive and anxiety symptoms for males, which was small.

Role of Negative Automatic Thoughts in the Linkage between Quality of Attachment Relationships and Psychological Problems

We expected that the quality of attachment relationships would directly and indirectly affect psychological problems. Bootstrapping was used to test the mediation hypothesis. Specifically, we tested the direct and indirect paths. In the mediation model, the mediating effect of negative automatic thoughts was estimated in the association between the quality of attachment relationships (maternal, paternal and peer) and psychological problems (symptoms of depression and anxiety). The models controlled for the effects of age and subject. None of the effects of these control variables on depressive and anxiety symptoms were significant. The fit indices showed that the model fit the data well (χ2 = 733.46, p = .000, χ2/df = 2.65, RMSEA = .04, TLI = .95). The specification and values of these models are presented in Table 2. Results indicate that, after controlling for negative automatic thoughts, all the direct paths from maternal and peer attachment to depressive and anxiety symptoms and paternal attachment to anxiety symptoms were non-significant. On the other hand, the path from paternal attachment to depressive symptoms was significant. The lower and upper limits of all the indirect paths did not include zero. In the pathways from maternal, paternal and peer attachment to depressive and anxiety symptoms, indirect effects were mediated through negative automatic thoughts. These results imply that negative automatic thoughts fully mediated the links of maternal and peer attachment with depressive and anxiety symptoms as well as between paternal attachment and anxiety symptoms because only indirect paths were significant. Whereas, negative automatic thoughts partially mediated the link between paternal attachment and depressive symptoms as both direct and indirect paths were significant. In view of these findings, the first hypothesis was supported. Moreover, all the paths were in the same directions as expected. Taken together, the quality of maternal, paternal, and peer attachment and negative automatic thoughts explained 54.5% of the variance in depressive symptoms and 54.1% of the variance in anxiety symptoms.

Moderating Effect of Gender in the Associations between Quality of Attachment Relationships, Negative Automatic Thoughts and Psychological Problems

We expected that gender would moderate the direct and indirect associations of maternal, paternal and peer attachment relationships with symptoms of depression and anxiety. To test the moderated mediation hypothesis, we applied the approach by Hayes (2015). The multi-group analysis was performed to examine the structural invariance of gender among the linkages. In this analysis, the parameters were estimated simultaneously in the invariant (measurement residuals model) and variant models (unconstrained model). The analysis produced a significant chi-square difference between the invariant and variant models [Δχ2 = 149.76 (1212.972–1063.212), df = 68 (622–554), p = .000]. Thus, results demonstrated that the links between the quality of attachment relationships, negative automatic thoughts, and psychological problems were different across gender. The controlled variables for the model did not show significant.

Differences in the invariance analysis lead to the diagnostic test for the moderated mediation model (Figs. 2 & 3; Hayes 2015). We found that the quality of maternal attachment had a significant effect on anxiety symptoms in males (β = .13, p = .02), and a non-significant effect on females (β = −.02, p = .68). In addition, link between peer attachment and anxiety symptoms were non-significant for both genders, however, beta value was positive for males (β = .03, p = .54) and negative for females (β = −.00, p = .95). Furthermore, the direct effect of maternal attachment on negative automatic thoughts was significant for females (β = −.17, p = .01) but not for males (β = −.05, p = .43). All other paths were in the same direction, as expected. Moreover, depression and anxiety mostly show causal sequence in comorbidity. A recent systematic review discovered that in emerging adult depressive symptoms or disorders often precedes the onset of anxiety symptoms or disorder (Johnson et al. 2018). Therefore, in the present study the direct effect of depressive symptoms on the anxiety symptoms was tested. It was found that direct link between depressive and anxiety symptoms is significant for males but non-significant for females. Such research outcomes show that the mediated model was moderated by gender, as some paths were different between males and females. Additionally, the direct effects of maternal, paternal, and peer attachment on depressive symptoms were non-significant for both genders. In contrast, the direct effects of negative automatic thoughts on all variables were significant for both males and females.

Further, the bootstrapping moderated mediation model provided a good fit (χ2 = 1212.97, p = .000, χ2/df = 1.95, RMSEA = .03, TLI = .95). As illustrated in Table 3, the formal test for the moderated mediation index revealed that the confidence intervals of the indexes for most of the paths excluded zero, indicated the mediating role of negative automatic thoughts among most of the paths in both genders. However, for males, the indirect path of maternal attachment to depressive and anxiety symptoms included zero, indicating a non-significant indirect effect. On the other hand, maternal attachment showed an indirect effect on females’ depressive and anxiety symptoms. Additionally, full mediation of negative automatic thoughts was found in the links between paternal and peer attachment with depressive and anxiety symptoms in both genders. Overall, the bootstrap analysis suggests that maternal, paternal and peer attachment as well as negative automatic thoughts explained 55.1% of the variance in depressive symptoms and 54.1% of the variance in anxiety symptoms in males. In contrast, 54.9% of the variance in depressive symptoms and 54.2% of the variance in anxiety symptoms in females were accounted for by maternal, paternal, and peer attachment, and negative automatic thoughts.

Discussion

The effect of parent-peer attachment on psychological problem has been robustly supported by empirical literature (e.g., Omidvar et al. 2015; Tambelli et al. 2012). Culturally, quality of attachment relationships is important in the development of Pakistani adolescents and their psychological problems. Additionally, the prevalence of psychological problems among youngsters in Pakistan is increasing, wherein differences between males and females have been observed (Khalid 2014). Therefore, it was deemed important to examine the roles of attachment relationships and negative automatic thoughts in the development of psychological problems among male and female. We tested a moderated mediation model on a large sample of Pakistani late adolescents. The findings suggested that the quality of maternal, paternal and peer attachments affected psychological problems through negative automatic thoughts. Moreover, the paths were moderated by gender. The present study extends the application of the attachment (Bowlby 1969) and cognitive (Beck 1967) theories to Pakistani adolescents by highlighting the roles of attachment quality and negative automatic thoughts in maintaining psychological health. Even though Pakistani adolescent sample was recruited for the current study, specific attachment patterns, family background and affectionate bonds may play more important roles than culture in maintaining adolescent’s psychological health. Therefore, most of the results of this study may be used to understand the causes of psychological problems in other cultures.

The study found that an insecure attachment relationship was linked with higher levels of negative automatic thoughts, which in turn, was positively linked with the psychological problems of late adolescents, thus supporting the first hypothesis. While extant literature (e.g Dhillon and Kanwar 2015; Omidvar et al. 2015; Yeh et al. 2014) has consistently underscored the impact of quality of attachment relationships on the psychological problems of adolescents, the present study reported its underlying mechanism in terms cognitive vulnerability. This study supports the cognitive theory which postulates that the presence of negative automatic thoughts would increase the probability of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Previous studies have highlighted that adolescents’ negative thinking patterns about the self and others may contribute to worry, fear and low mood (Beck and Haigh 2014; Hjmedal et al. 2013). However, relationships with parents and peers can be the major sources of thought formulations (Laghi et al. 2016; Park et al. 2016). A high level of trust and good communication with parents and peer can help adolescents feel accepted, supported and loved. Thus, secure attachment with parent and peers is helpful to adolescents to form positive thoughts about the self and others. For most psychological problems, secure attachment with parents and peers would decrease negatively biased interpretation of experiences and relationships with others. The findings are also in line with the attachment theory which emphasizes the role of IWMs and quality of attachment relationships (Bowlby 1969, 1973, 1982).

Late adolescence is considered to be a time of stress as young individuals goes through varied kinds of stressors including professional problems, academic issues, separation from parents, role confusion, marriage-related issues, and formation of new relationships, among others (Curtis 2015). During this stage, secure attachment relationships with parents and peer and adaptive IWMs become protective factors against the development of psychological problems. Bowlby (1969, 1973) highlighted that having rejecting and insensitive caregivers contributes to maladaptive IWMs that are inconsistent and contain relationship-related emotional pain. Moreover, IWMs mostly operate at the unconscious level because the interaction pattern becomes ingrained and habitual; hence, becoming automatic and less open to conscious control (Bowlby 1980). This is similar to Beck’s idea that negative automatic thoughts are easily assessable and are developed since childhood. According to the cognitive model, the negative triads are the major causes of most depressive and anxiety symptoms (Beck 1967; Beck and Haigh 2014). The present study proposed negative automatic thoughts as a mediating variable which can explain the integration of attachment and cognitive theories. The results supported the assumption and theoretical integration.

In the context of Pakistan, which is a low-income country with many problems (World Bank 2018), having a good relationship with significant others who provide comfort during stressful situations (i.e., academic problems, profession-related issue, marriage-related issues, financial issues, peer problems) and promote positive thinking in adolescents, such as considering themselves as viable persons, the world as a safe place to live in, and that others will offer help when needed, is vital in decreasing the potential for negative developmental outcomes such as psychological problems. In the collectivistic culture of Pakistan, a high value is given to the family, perceived family support as well as relationships with parents and peers. Moreover, parental control in the country is considered as a manifestation of sincerity by the parents towards their child; however, too much attention accorded by parents to their child may become undesirable to the teens (Baig et al. 2014). In the current study, the quality of relationship with the mother, father and peers emerged as significant predictors of psychological problems among youngsters. However, the magnitude of the indirect effect indicates a small effect size of maternal attachment on depressive and anxiety symptoms; whereas, the effects of paternal and peer attachment on depressive and anxiety symptoms had medium effect sizes.

The findings of this study also confirmed the moderating effect of gender in the direct and indirect linkages between parent-peer attachment relationships and psychological problems. For instance, no mediation effect was found in the association between maternal attachment and depressive and anxiety symptoms for males; but, maternal attachment indirectly predicted psychological problems through negative automatic thoughts in females. These are significant findings which are, in fact, consistent with those of previous studies (e.g., Ho et al. 2018; Laghi et al. 2016; Park et al. 2016). Culturally, Pakistani males generally start to separate from their primary caregiver during late adolescence and identify more with their father than with their mother. On the contrary, females use their socialization role and various maternal experiences to define the self, based on their relations with others and their concern to retain relationships. The continuous interest of females in maintaining their relationships can be considered a protective factor against psychological problems when the relationship is healthy, and a risk factor when relationships are unsatisfying (Naz and Kausar 2013). Additionally, the findings demonstrated that insecure paternal attachment plays a significant role in the formation of maladaptive cognitions and psychological problems for both genders. The results were consistent with the theoretical integration and recent literature showing that, although the mother is important, the father also plays a vital role in the emotional adjustment of both daughters and sons (Babore et al. 2016). A similar pattern was observed in Pakistan by Rizvi (2015), in which early adolescent males and females considered their fathers to be engaged and involved in rearing them.

The findings suggest that males and females may have different interpretations of attachment with the mother and father, which impact their developmental outcomes distinctively. These gender differences underscored the impact of gender-role socialization in Pakistan, which is predominantly patriarchal, and also depicted the modification in the norms and values of society (Irfan 2016). In the Pakistani culture, males during late adolescence are expected to work by choosing a professional degree instead of conventional studies; whereas, females’ emotional, educational, and financial needs even until marriage are still taken care of by their parents (Imtiaz and Irum Naqvi 2012; Irfan 2016). Throughout their lives, males respect and are emotionally attached to their mothers. Maternal affection to the child is undoubtedly viewed as unconditional. However, over involvement of the mother may hinder autonomy in adolescents that may consequently decrease their perceived maternal attachment security. This could be the reason that no significant effect was observed between quality of maternal attachment and psychological health of male adolescents. On the other hand, fathers in the Pakistani society are the dominant head of the family, take charge of the finances of all the family members, and make most of the decisions in the family. Nonetheless, due to the increase of financial issues, the migration from rural to urban areas, and the upsurge of nuclear families, mothers have also started working to meet the financial needs of the family. It was observed in the current study that most of the adolescents belonged to the average or below average income families. Additionally, we found that almost 7 % of the respondents’ mothers were employed, highlighting role shifting in Pakistan. Accordingly, attachment with the father emerged as a prominent factor in the development of both male and female adolescents.

Another interesting finding of the current study was the significant direct positive association of maternal attachment relationship with the anxiety symptoms in males. These findings can be explained though developmental perspectives which asserted that adolescent males are expected to work on achieving autonomy in different aspects of life (Daddis and Smetana 2005). On the other hand, the attachment theory posits that autonomy seeking behaviors in adolescence may create problems in the relationship between primary caregiver and a child (Allen and Tan 2016). In Pakistan, fostering of adolescent’s autonomy is lacking (Imtiaz and Irum Naqvi 2012). For the male child in Pakistan, the mother is mostly the source of emotional support. However, high levels of emotional dependence on the mother may hinder the development of males’ autonomy and independence that may result in distress, then anxiety. Moreover, this unexpected direct effect suggests theoretical progress (Zhao et al. 2010). The presence of significant direct effects highlights the importance of testing other mediators which may have the same effect on the relationship between quality of maternal attachment and anxiety. Therefore, it is recommended that future research should address the complexity of the quality of maternal and paternal attachment and the environmental factors as predictors of male and female psychological problems across developmental stages.

Furthermore, contrary to previous findings (e.g., Laghi et al. 2016) which highlighted that secure peer attachment decreases negative cognitions and internalizing problems in females, the results of the present study demonstrated that, for both males and females, peer attachment influenced depressive and anxiety symptoms through negative automatic thoughts. Limited studies are available on gender differences on the influence of peer attachment on depressive and anxiety symptoms through negative automatic thoughts. Nonetheless, earlier studies suggested that college students generally comprise homogeneous samples in terms of values, the roles they have to display and the expectations for males and females (Hammen and Padesky 1977). This might be the reason for the lack of gender differences observed on the indirect effect of the quality of peer attachment on the depressive and anxiety symptoms of late adolescents. Previous studies in Pakistan (e.g., Irfan 2016) did not find differences between males’ and females’ perceptions about peer influence and its impact on psychological wellbeing. At this critical period, peers are important in fostering specific developmental domains for both genders, particularly those related to emotional regulation as well as psychosocial and cognitive aspects. The initiation of detachment (separation) from parents forces them to seek support or a platform from which they can securely explore the world thus, peer attachment become important for both male and female. Overall, these results showed that the quality of attachment to the mother, father and peers each has a distinct effect on the working models and psychological problems of Pakistani male and female late adolescents.

Taken together, the main contribution of the present study is the investigation of a moderated mediation model using a non-western sample. This model is an important addition to the literature on attachment (Bowlby 1969, 1982) and cognitive (Beck 1967) theories and provides the non-western society like Pakistan’s perspective on these theories. Primarily, negative automatic thoughts emerged as an important mediation mechanism and that gender is one way to account for heterogeneity in the impact of parent and peer attachment on symptoms of depression and anxiety among late adolescents. In addition, this study reported distinct roles of maternal, paternal and peer attachment in the development of depressive and anxiety symptoms in male and female late adolescents, which add to the literature on the differential development of males and females specifically in Asia (e.g., the Pakistani context). This study extends the literature on the predictors of depressive and anxiety symptoms and mediating and moderating mechanisms that lead to these psychological problems. Moreover, the findings of current study also have some clinical implications for the treatment and prevention of depression and anxiety among adolescents. Prevention and intervention programs should focus on modifying the negative thoughts about self, others and world formed in response to the problems in interpersonal relationships. Previous studies also supported teaching cognitive techniques to adolescents to reduce the risk of developing anxiety and depression (Oar et al. 2017). Additionally, the findings suggested that while working with adolescents specifically in Asian context, special attention needs to be given to improve the quality of relationship with mother (for girls), father or/and peers (for both gender). Past studies have also revealed that attachment-based therapies were very helpful in reducing the risk for psychological problems among adolescents (Kobak et al. 2015).

Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations which need to be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, this study was cross-sectional in nature; hence, causal relationships among variables were not investigated. Longitudinal studies would be more useful to clarify the linkages between quality of attachment relationships, automatic thoughts and psychological problems in different developmental stages. Attachment and IWMs begins developing during early years of life therefore future studies may investigate these associations in childhood, adolescence and adulthood. This will provide a better understanding of the development and reconceptualization of attachment relationships and IWMs over the course of development and its impact on the psychological outcomes of an individual. Secondly, the data were collected only through adolescents’ self-report, which may produce common method variance. Future studies must collect data from multiple informants (e.g., parents or peers) to understand whether the results would be the same or not, and/or may use observational method and clinical interviews to assess these constructs. Thirdly, the data were only collected from a normal sample. Studying the same paths among the clinical sample already diagnosed with psychopathology will also be helpful in formulating an effective intervention plan.

Fourthly, this study recruited participants only from the government college in Rawalpindi district. A recent report published by Government of Pakistan (2017) indicated that at Inter College level or Grade 11th and 12th or higher secondary, out of 1.697 million the 1.325 million students are registered in public sector institutions. Therefore, this sample can be said as representative of the late adolescents studying in the colleges of Pakistan. However, readers should be cautious when generalizing the results to diverse groups such as private or semi-government colleges or late adolescents who are not studying in colleges. Additional pathways among the variables must be investigated to see other associations, such as the view that children’s psychological problems may have an effect on their quality of relationship with attachment figures, children of depressed or anxious attachment figure may likewise affect their relationship with significant others and their psychological health. Furthermore, literature suggests that, in late adolescence, peers and romantic partners enter at the primary level of the attachment hierarchy and play an important role in the psychological health of an individual. We only investigated the impact of the quality of friendship on psychological problems. Relationship with romantic partner specifically illegitimate is not disclosed in Pakistani society because of close knitting family system and practising of Islamic norms. However, a study showed that due to societal change, globalization, and technology usage without awareness and proper check the probability of having romantic partner has been increasing among youth (Sheikh et al. 2015). Future studies are therefore encouraged to investigate when and how attachment with romantic partner is developed, impact of relationship with romantic partner/s on the psychological health of youngsters, predictors of romantic partner’s attachment among married and unmarried person in Pakistan and also the gender differences among these associations. Differences in environmental stressors, socioeconomic backgrounds, caregiving situations (e.g., single parent, siblings, and grandparents) and negative life events were also not evaluated, suggesting the need to explore these constructs in future studies.

References

Ahmed, B., Enam, S., Iqbal, Z., Murtaza, G., & Bashir, S. (2016). Depression and anxiety: A snapshot of the situation in Pakistan. International Journal of Neuroscience and Behavioral Science, 4(2), 32–36. https://doi.org/10.13189/ijnbs.2016.040202

Ahmad, R., & Bano, Z. (2013). Translation and psychometric assessment of social anxiety scale for adolescents in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Psychology, 44(1), 67–80.

Ainsworth, M. S. (1989). Attachments Beyond American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. hhttps://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709

Allen, J. P., & Tan, J. S. (2016). The multiple facets of attachment in adolescence (399-415). In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 102–127). New York: Guilford Press.

Alsaleh, M., Lebreuilly, R., Lebreuilly, J., & Tostain, M. (2016). Cognitive balance: States-of-mind and mental health among french students. Best Practice in Mental Health, 11(1), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcc.2016.02.002

Amaltinga, A. P. M., & Mbinta, J. F. (2020). Factors associated with depression among young people globally: A narrative review. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 7(9), 3711–3721. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20203949

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16(5), 427–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02202939

Armsden, G. C., McCauley, E., Greenberg, M. T., Burke, P. M., & Mitchell, J. R. (1990). Parent and peer attachment in early adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18(6), 683–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01342754

Babore, A., Trumello, C., Candelori, C., Paciello, M., & Cerniglia, L. (2016). Depressive symptoms, self-esteem and perceived parent-child relationship in early adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(982). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00982

Baig, N., Rehman, R. R., & Mobeen, N. (2014). A parent-teacher view of teens behaviors in nuclear and joint family systems in Pakistan. The Qualitative Report, 19(34), 1–12. Retrieved from https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss34/1

Beck, A. T. (1963). Thinking and depression: I. Idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 9(4), 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1963.01720160014002

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical experimental and theoretical aspects. New York: Harper & Row.

Beck, A. T., & Haigh, E. A. P. (2014). Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: Generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annuarev-clinpsy-03813-153734

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. I. Loss sadness and depression. NY: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. II. Attachment & Loss. United States of America: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss. NY: Basic Books. Retrieved from http://www.abebe.org.br/wp-content/uploads/John-Bowlby-Loss-Sadness-And-Depression-Attachment-and-Loss-1982.pdf

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. I. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Breinholst, S., Tolstrup, M., & Esbjørn, B. H. (2019). The direct and indirect effect of attachment insecurity and negative parental behavior on anxiety in clinically anxious children: it's down to dad. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(1), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12269

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: The Guilford Press.

Brown, H. M., Waszczuk, M. A., Zavos, H. M. S., Trzaskowski, M., Gregory, A. M., & Eley, T. C. (2014). Cognitive content specificity in anxiety and depressive disorder symptoms: A twin study of cross-sectional associations with anxiety sensitivity dimensions across development. Psychological Medicine, 44, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000828

Clayborne, Z. M., Varin, M., & Colman, I. (2019). Systematic review and meta-analysis: Adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(1), 72–79.

Clear, S. J., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2015). Associations between attachment and emotion-specific emotion regulation with and without relationship insecurity priming. International Journal of Behavioral Development., 41(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415620057

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Routledge Academic.

Cummings, C. M., Caporino, N. E., & Kendall, P. C. (2013). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: 20 years after. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 816–845. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034733

Curtis, A. C. (2015). Defining adolescence. Journal of Adolescent and Family Health, 7 (2), doi: http://scholar.utc.edu/jafh/vol7/iss2/2

Daddis, C., & Smetana, J. (2005). Middle-class African American families’ expectations for adolescents’ behavioural autonomy. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 371–381.

Dhillon, R., & Kanwar, P. (2015). Relationship of perceived parental attachment with internalizing problems among adolescents (abstract). Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 6(2), 171–173. Retrieved from http://www.iahrw.com/index.php/home/journal_detail/19#list

Dumont, C., & Paquette, D. (2013). What about the child's tie to the father? A new insight into fathering, father–child attachment, children's socio-emotional development and the activation relationship theory. Early Child Development and Care, 183(3–4), 430–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2012.711592

Fraley, R. C. (2019). Attachment in adulthood: Recent developments, emerging debates, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102813

Furman, W. (2001). Working models of friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18(5), 583–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407501185002

Garber, J., & Weersing, R. V. (2011). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in youth: Implications for treatment and prevention. Clinical Psychology, 17(4), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01221.x

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L. & Black W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th Edition). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hammen, C. L., & Padesky, C. A. (1977). Sex differences in the expression of depressive responses on the Beck depression inventory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 86(6), 609–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.86.6.609

Hankin, B., Young, J., Abela, J., Smolen, A., Jenness, J., Gulley, L., Technow, J., Gottlieb, A. B., Cohen, J., & Oppenheimer, C. (2015). Depression from childhood into late adolescence: Influence of gender, development, genetic susceptibility, and peer stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(4), 803–816. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000089

Hashmi, H. A. (2012). Translation, validation, adaptation of automatic thoughts questionnaire to assess the relations of negative thoughts with depression. United States of America, Middletown DE: Amazon.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Journal Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

Hjmedal, O., Stiles, T., & Wells, A. (2013). Cognition and neurosciences automatic thoughts and meta-cognition as predictors of depressive or anxious symptoms: A prospective study of two trajectories. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 54, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12010

Ho, S. M. Y., Dai, D. W. T., Mak, C., & Liu, K. W. K. (2018). Cognitive factors associated with depression and anxiety in adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 18(3), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2018.04.001

Hollon, S. D., & Kendall, P. C. (1980). Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 4(4), 383–395.

Holt, L., Mattanah, J., & Long, M. (2018). Change in parental and peer relationship quality during emerging adulthood implications for academic, social, and emotional functioning. Journal of Social and Personal Relationship, 5(5), 743–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517697856

Howes, C., & Spieker, S. (2016). Attachment relationships in the context of multiple caregivers. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 314–329). New York: The Guilford Press.

Imtiaz, S., & Irum Naqvi, I. (2012). Parental attachment and identity styles among adolescents: Moderating role of gender. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 27(2), 241–264.

Imran, S., Angus MacBeth, A., Quayle, E., & Chan, S. W. Y. (2020). Secondary attachment and mental health in Pakistani and Scottish adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12280

Irfan, M. (2013). Integration of mental health in primary care in Pakistan. Journal of Postgraduate Medical Institute, 27, 349–51. https://jpmi.org.pk/index.php/jpmi/article/view/1573

Irfan, U. (2016). Mental health and factors related to mental health among Pakistani university students (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/13342/Irfan%2C%20Uzma%20Final%20PhD%20thesis%20Amendment%2027%20Feburary.pdf?sequence=4

Irfan, S., & Zulkefly, N. S. (2020). A pilot study of attachment relationships, psychological problems and negative automatic thoughts among college students in Pakistan. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health., 0. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2019-0264

Jin, Y., He,L., Kang, Y., Chen, Y., Lu, W., Ren, X., Song, X., Wang, L., Nie, Z., Guo, D., & Yao, Y. (2014). Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety status among students aged 13-26 years. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 7(11), 4420–4426. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4276221/

Johnson, D., Dupuis, G., Piche, J., Clayborn, Z., & Colma, I. (2018). Adult mental health outcomes of adolescent depression: A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety, 35, 700–716. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22777

Khalid, A. (2014). Correlates of Mental Health among Pakistani Adolescents: An exploration of the interrelationship between attachment, parental bonding, social support, emotion regulation and cultural orientation using Structural Equation (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1842/15925

Kline, R. B. (2005). Methodology in the social sciences. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Kobak, R., Zajac, K., Herres, J., KrauthamerEwing, E., & S. (2015). Attachment based treatments for adolescents: The secure cycle as a framework for assessment, treatment and evaluation. Attachment and Human Development, 17(2), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2015.1006388

Laghi, F., Pallini, S., Baumgartner, E., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Parent and peer attachment relationships and time perspective in adolescence: Are they related to satisfaction with life? Time & Society, 25(1), 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X15577282

Lee, A., & Hankin, B.L.(2009). Insecure attachment, dysfunctional attitudes, and low self-esteem predicting prospective symptoms of depression and anxiety during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38 (2), 219-231. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802698396

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Love, K. M., & Murdock, T. B. (2012). Parental attachment, cognitive working models, and depression among african American college students. Journal of College Counselling, 15 117–129. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2012.00010.x

Oar, E. L., Johnco, C., & Ollendick, H. (2017). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 40(4), 661–674.

Omidvar, B., Bahrami, F., Fatehizade, M., Etemadi, O., & Ghanizadeh, A. (2015). Attachment quality and depression in iranian adolescents. Psychological Studies, 59(3), 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-014-0250-1

Margolese, S. K., Markiewicz, D., & Doyle, A. B. (2005). Attachment to parents, best friend, and romantic partner: Predicting different pathways to depression in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(6), 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-8952-2

Mesman, J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Sagi-Schwartz, A. (2016). Cross-cultural patterns of attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 852–877). New York: Guilford.

Naveed, S., Qadir, T., Afzaal, T., & Waqas, A. (2017). Suicide and its legal implications in Pakistan: A literature review. Cureus, 9(9), e1665. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.1665

Naz, F., & Kausar, R. (2013). Parental rejection, personality maladjustment and depressive symptoms in female adolescents in Pakistan. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 14 (1), 56–65. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7ce7/d28135dbdb25807dcc68b71c08e1ddd5616e.pdf