Abstract

Marriage rates in Indonesia are some of the highest in Asia as marriage is socially expected. Indonesian individuals who remain single beyond the age at which marriage is expected face stigmatization, such as being objects of pity or being labelled as selfish, too picky, or homosexual. Social stigmatization has consequences for feelings of belonging, which Internet use may be able to address. The Internet may allow singles to fulfil their social needs and possibly also fulfil their recreational and sexual needs, thus potentially contributing to singles’ welfare. However, there are few studies that explore the role of the Internet in assisting individuals who have never married to fulfil their leisure and social needs. This study investigates whether and how Internet use enhances single people’s well-being in Indonesia. A sample of 559 single and married Indonesians (Mage = 31.68; SD = 5.54), of which 310 were never-married, participated in an online survey, where their Internet use, life satisfaction, loneliness, and online social support were recorded. Data were primarily analyzed using hierarchical regression, one-way ANOVA, and Pearson’s correlation. The study found that single people who were in dating relationships used the Internet significantly more than married people, and the majority of Internet use was for recreational purposes and viewing pornography. The well-being of never-married Indonesian people was not significantly associated with their Internet use and their perceived social support from online contexts, thus highlighting the importance of face-to-face interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There has been considerable research into the global increase in individuals remaining unmarried (DePaulo and Morris 2005; Himawan 2020b; Jones 2018; Morris et al. 2016; Slonim et al. 2015). The growth in the numbers of people remaining single is not just a Western phenomenon. Singleness is also increasing in Asian countries (Himawan et al. 2018a; Jones 2018), within which marriage is regarded as a religious or cultural obligation. Indonesia is an example of such an Asian country where marriage is an expectation and there are social consequences for not marrying at the expected age (e.g. being labelled homosexual, self-centered, or being stigmatized as a ‘tidak laku’ [leftover]) (Himawan et al. 2018b). In Indonesian culture, heterosexual relationships within the context of monogamy are the norm; labels linked to tidak laku, selfishness, and/or homosexual behaviors are all stigmatizing.

Numerous international studies about singleness often associate the status of never being married with a stigmatizing experience since being in a state of singleness does not meet social and cultural expectations (Darrington et al. 2005; DePaulo and Morris 2016; Himawan 2020a). From the stigmatization perspective, it is imperative to explore various sources to determine how individuals who never have been married cope with this type of stigmatization. While the concept of modernization has been used to explain the phenomenon of delayed marriage age or never marrying (Himawan et al. 2019a), modernization is also linked to increasing Internet use (Kluver and Cheong 2007), which provides more social and relationship options and potential sources of personal fulfilment (Malcolm and Naufal 2014; Manning 2006). The present study particularly focuses on examining the effectiveness of the Internet in providing necessary sources to assist never married individuals in mitigating their challenges.

Given the popularity of social networking and online interactions, the Internet may offer a promising source of support to promote well-being and to manage various life challenges (Chong et al. 2015; Knobloch-Westerwick et al. 2013). The Internet offers a variety of leisure activities (Leung and Lee 2005) and has been shown to be an effective medium for providing social support (Chung 2013; LaCoursiere 2001). Social support has been suggested as a key coping mechanism for individuals who never married, particularly in reducing loneliness (Pinquart 2016). Nonetheless, to date, there has been little investigation of the role of the Internet and how it may be used to mitigate the negative social effects of being single.

In Indonesia, Internet use has increased dramatically. A recent survey indicated that 64.8% of Indonesian people are active Internet users – an increase of 10% from the previous year (Asosiasi Penyelenggara Jasa Internet Indonesia 2018). More interestingly, the survey also found that the main reasons (43.6%) for Internet activities are for socialization (using social media, communicating with others, and, belonging to online communities). While this provides evidence that more Indonesian people are utilizing the Internet to fulfil their social needs, to our knowledge, there has been no published study regarding the role of Internet for never-married individuals, the proportion of whom continues to grow (Himawan et al. 2019a).

The current study aims to explore Internet use by single people in relation to their well-being, particularly life satisfaction and levels of loneliness. Himawan et al. (2019a) suggested that online social support might increase the coping capacity for single people to deal with stigma and loneliness. This study examines this proposition in more detail.

The Internet and the Well-Being of Single People

The Internet has greatly influenced the Indonesian lifestyle over the last two decades. The Internet can be used for a range of reasons such as researching information, entertainment, social support, socialising including meeting potential partners, as well as for immediate sexual gratification, such as using pornography (Hamburger and Ben-Artzi 2000; Mesheriokova and Tebb 2016; Schlarb and Brandhorst 2012; Wellman and Haythornthwaite 2002). Leung and Lee (2005) identified four areas individuals use the Internet: recreation, socializing, interests and self-education, and e-commerce. Single people are thought to have more leisure time than married people (Wang and Abbott 2013). If the Internet is considered as a potential coping source, single people may plausibly experience greater benefits from Internet use than married individuals, and thus the frequency of their Internet use may be associated with their well-being.

The use of the Internet to access pornographic materials in Indonesia is a complex issue due to social and moral sanctions. Therefore, the extent of online pornography use in Indonesia is largely unknown. The gratification of sexual desire through the Internet might be preferred by individuals who are single, rather than having a non-marital sexual relationship. This is because non-marital sex in Indonesia is not only seen as taboo (Bennett 2000) but it is also considered criminal conduct (Fachrudin 2016). Little is known about the impact of pornography, whether positive or negative,on the well-being of single people – a factor this study explores.

Internet use is also proposed to facilitate social support for single people, especially as they deal with loneliness. Loneliness is a common problem reported by single people in Asia (Himawan et al. 2018a). In a qualitative study of never-married females aged over 30 in China, Wang and Abbott (2013) demonstrated that loneliness is one of the most reported experiences related to singleness. Loneliness might be experienced even more intensely by those who are involuntarily single (Adamczyk 2017). With increased risk of feeling lonely, single people are more prone to relying on the Internet to deal with loneliness (Schou Andreassen et al. 2016). In addition to that, individuals who are single may feel lonely because they lack a relationship partner, and/or because of limited social support due to the stigmatization of unmarried people. The Internet could facilitate social support through various social media by enabling social interactions, thereby allowing them to communicate and support each other (Shaw and Gant 2002).

Many studies have demonstrated the positive impact of online social support (Chung 2013; Leung and Lee 2005; Watkins and Jefferson 2013), although no studies examined its impact on single adults. Likewise, the impact of gender on any dimensions of Internet use among individuals who are single remains unknown. However, the association between Internet use and life satisfaction may be more significant for females (Lachmann et al. 2016), because females tend to use the Internet more for social networking, while males tend to pursue recreation, such as online gaming and viewing pornography (Dufour et al. 2016; Odacı and Çıkrıkçı 2014).

Asian studies about the role of the Internet in developing different types of intimacy are gaining in popularity (Cabañes and Uy-Tioco 2020). In Korea, for example, the use of mobile messaging applications has been found to provide emotional support to the most stigmatized demographic group, Ajumma (middle-aged married females described as self-centered, aggressive, and shameless) (Moon 2020). In India, there is an increasing prevalence of young adults utilizing dating applications, mainly for sexual expression (Chakraborty 2019). Online dating websites are also prevalent and perceived as beneficial for Singaporean never-married adults (Phua and Moody 2018). In Indonesia, there has been a lack of scholarship pertaining to this topic, despite having high mobile and Internet penetration rates (Cabañes and Uy-Tioco 2020).

The Study Context: Singleness in Indonesia

The latest census data in Indonesia showed that more than 7 % of individuals aged 30–39 years had never married (Badan Pusat Statistik 2010). Jones (2007) found that the rate of females never marrying in Indonesia had almost tripled (4.9%) over four decades. The age of marriage has also increased by three years compared with that of four decades ago (Badan Pusat Statistik 2010; Jones 2010). Those indications suggest that singleness is a growing phenomenon in Indonesia.

The growing number of single people has not led to a reduction of stigma or greater social acceptance. In Indonesia, if people have not married by the age it is socially expected (30 year of age), they are seen as an object of pity by their communities and often withdraw socially to avoid feeling ashamed (Situmorang 2007). The negative connotations attached to individuals who remain single include: being labelled as having a homosexual orientation, selfish, or too picky (Himawan et al. 2018b; Situmorang 2007). As was stated above, such labels are meant as insults and are stigmatizing. While such stigmatization is argued to be more intensely experienced by single females, particularly within their 30s (Jones 2018), we have reported elsewhere that both males and females feel social pressure to marry, and describe this pressure as moderate to strong (Himawan 2020a; Himawan et al. 2019b).

Despite having to endure social pressures and stigmatization, single people in Indonesia have a strong need to feel accepted and to belong to a community, especially in the absence of romantic partners (Himawan et al. 2018c). Baumeister and Leary (1995) argue that humans have a fundamental need to belong which plays an important role in life satisfaction. This position is consistent with Erikson’s (1997) psychosocial stages of development, which highlights the importance of young adults in forming and maintaining a stable, intimate relationship to gain the virtue of love. Indonesian culture defines the marital relationship as the ideal institution to meet the individual’s need to belong in a family, a community, and a society. However, being single does not mean that those needs cannot be met. Single people can often build deeper and more intimate relationships with their parents, families or friends (DePaulo 2013). Therefore, having cohesive social support could be an important coping strategy in dealing with social stigma. While studies have demonstrated the possible link between loneliness and Internet use (e.g. Odacı and Kalkan 2010), there is no study that explores the role of online social support for single individuals, especially among those whose society considered marriage as the norm.

Present Study

The current study aims to examine the association between Internet use and single individuals’ levels of life satisfaction and loneliness. The term ‘single’ is used in this study to refer to those who are legally single (DePaulo and Morris 2016), which includes individuals who have never been married, but does not include widows/widowers or divorcees. Thus, single in this study includes unmarried individuals regardless of whether or not they are in a dating relationship. Study samples were separated into three groups for analysis: single, single in a relationship, and married. Identifying single people who are and are not in a romantic relationship is considered important since the presence of a romantic partner might prevent single people from experiencing romantic loneliness (Adamczyk 2017). Internet use is described in terms of participants’ levels of engagement in various Internet activities (i.e. fun seeking, sociability, information seeking, e-commerce, and accessing porn materials) and perceived social support gained through online.

The present study investigates three hypotheses:

-

H1: Perceived online social support would be positively associated with single people’s levels of life satisfaction and would be negatively associated with their levels of loneliness.

-

H2: Individuals who are never married would spend significantly more time on the Internet than their married counterparts.

-

H3: Certain Internet activities would meet (in part) the social, sexual, and psychological needs of single people, which would be reflected in higher scores of life satisfaction and lower scores of loneliness.

Method

Participants

Participants were Indonesian adults recruited through convenience sampling who responded to the social media invitations (e.g. Facebook and Instagram). The participants met the following criteria: 1) being male or female aged between 26 and 50 years, 2) never married, and 3) having a heterosexual orientation. Homosexual single people were excluded as they face different social challenges including the risk of prosecution as homosexuality is illegal in Indonesia. For the control group, married participants were recruited according to the same gender, age and sexual orientation criteria. Participants completed an online survey that recorded their Internet use, perceived online social support, loneliness, and life satisfaction, along with their demographic information.

To determine the sample size, calculations were performed using the G*Power program version 3.1 (Faul et al. 2009) to identify the minimum sample required for the various statistical models for each hypothesis. For a medium effect size (f2 = .30) and a non-directional alpha of .05, the minimum number suggested was 226 for each group. Given the lack of published research to guide power analysis, over-recruitment was attempted to account for unknown sample variability. This study was approved by The University of Queensland Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: 2017000826). The study was in compliance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later addenda.

Procedures

A back-translation procedure was employed, in which study instruments were translated into Indonesian (by the first author), and then translated back into English (by an independent bilingual scholar). Any differences between the original and back translated English versions were discussed among the authors until consensus was reached, which resulted in a revised Indonesian version that reflects higher accuracy than when it was first translated. The survey consisted of the final Indonesian translation of the instruments. The translated instruments in this study were: The Internet Activities Scale (Leung and Lee 2005), The Online Social Support Scale (Wang and Wang 2013), the Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985), and the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Hays and DiMatteo 1987).

The Indonesian language survey was conducted using the Survey Monkey platform between March – July 2019. Participant recruitment were conducted through social media channels, including: Facebook, Whatsapp, and Instagram. The first author advertised the survey recruitment poster in their social media accounts. Participants provided informed consent by clicking on an agree icon after reading the study information. The survey system was set up to only allow a single response for each user based on their Internet Protocol (IP) address. Survey participation took approximately 15 min. As an incentive for participation, participants went into a drawing to win one of five shopping vouchers valued IDR 100.000,- (equal to roughly US$7) each. Only completed data sets were used for the main analysis.

Instruments

Demographic Data

Participants were asked to provide information pertaining to several demographic variables: age, gender, educational level, sexual orientation, dating history, and relationship status. For single participants, they were also asked to indicate whether they were voluntary or involuntary single people.

Internet Activities

The Internet Activities section of the survey consisted of five items designed to record participants’ levels of engagement in various types of online activity. In addition, participants were asked about their average amount of time the used the Internet per day (On average, how frequently do you use the Internet every day?). Their responses were coded from 1 to 7 (1 = less than 1 h a day, 2 = less than 2 h a day, 3 = less than 3 h a day, 4 = less than 4 h a day, 5 = less than 5 h a day, 6 = less than 6 h a day, and 7 = more than 6 h a day). Next, participants indicated how frequently they used the following Internet activities as defined by Leung and Lee (2005): fun seeking, sociability, information seeking, and e-commerce, with an additional category: pornography. Examples of activities were provided for each category. For instance, participants were asked: “How frequently do you use the Internet for the following activities? 1. Fun seeking (includes: online video games, listening music, watching videos, and recreational browsing), 2. Sociability (includes: chatting with friends or strangers online, interacting through social media, and posting status updates or photos on social media platforms), 3. Information seeking (includes: reading news, learning new information online), 4). e-Commerce (includes: an online transaction, paying bills), and 5. Accessing pornography (includes: enjoying pornography contents). Participants scored their responses on a scale of 1–5 (1 = never, 5 = always).

The Online Social Support Scale (OnSSS)

The OnSSS is a scale adapted by Wang and Wang (2013) to measure individuals’ perceived social support from online communities. The scale has been used in previous studies (e.g. Mazzoni et al. 2016) and demonstrated good psychometric properties. There were 11 items addressing the forms of online support received. The scale consisted of three dimensions: Emotional and Informational (sample item: “someone whose advice you really want”), Positive Social Interaction (sample item: “someone you can do something enjoyable with”), and Affectionate (sample item: “someone you can count on to listen to you when you need to talk”). The Indonesian Version of the OnSSS produced a Cronbach’s alpha of .914, .935, and .940, for the Emotional and Informational, Positive Social Interaction, and Affectionate dimensions, respectively. When taken together, the Cronbach’s alpha was .958 (α was .966, .957, and .967 for single, single in a relationship, and married participants, respectively).

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

Developed by Diener et al. (1985), the scale consisted of five items measuring individuals’ level of overall life satisfaction (sample item: In many respects, my life is close to ideal). Participants responded using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The current Indonesian version of SWLS had a Cronbach’s alpha of .855 (α was .876, .822, and .833 for single, single in a relationship, and married participants, respectively).

The UCLA Loneliness Scale – 8 Items (ULS-8). The scale was originally developed by Russell et al. (1978), and the shorter version, which was used in this study, was created by Hays and DiMatteo (1987). It consisted of eight items measuring individuals’ levels of loneliness, to which participants responded using a 4-point scale (1 = never, 4 = always) (sample item: I lack friends). Responses on items 3 and 5 were inverted. The Indonesian version of ULS-8 yielded an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha (α = .728) (α was .737, .790, and .703 for single, single in a relationship, and married participants, respectively).

Data Analytic Strategy

Hypotheses were tested using the Pearson correlation test, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), and regression analysis. A hierarchical regression model was developed using online social support scores as the predictor (Independent Variable; IV) of single people’s life satisfaction (Dependent Variable 1; DV1) and loneliness (Dependent Variable 2; DV2). All analyses were done using Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 17.

Results

Characteristics of the Participants

A total of 559 participants (Mage = 31.68; SD = 5.54) completed the online survey; 55.46% (n = 310) were never married and 70.3% (n = 393) were females. Table 1 provides a detailed summary of participants’ demographic characteristics.

Several sub-categorizations were made to allow a discrete analysis of variables. Single people were categorized based on whether they were in a relationship (38.1%; Mage = 29.19; SD = 3.796) or not (61.9%; Mage = 30.33; SD = 4.961). Single people were also categorised on the basis of their motives for being single [voluntary singles (7.1%) and involuntary singles (92.9%)] and age [younger (26–35 years; 88.7%) and older (>35 years; 11.3%)]. However, due to the difference in numbers between voluntary–involuntary and younger–older groups, analyses could not be performed based on these sub-categorizations.

Correlations among Study Variables

Table 2 provides a summary of correlations among several study variables.

Online Social Support, Life Satisfaction, and Loneliness among Individuals Who are Single (H1)

The relationship between offline social support, life satisfaction, and loneliness were tested using hierarchical multiple regression analyses (see Table 3). Gender and age were entered in the first block, and Online Social Support scores were included in the second block. Results showed that online social support was not a meaningful predictor of participants’ life satisfaction (β = .039; p = .495) and loneliness (β = .022; p = .693). Therefore, H1 was not supported.

Furthermore, an examination of the regression model indicated that dating status (single versus single in a relationship) did not affect participants’ life satisfaction and loneliness (see Table 4). Hence, the findings revealed that online social support was not a meaningful predictor of single people’s well-being, regardless of dating status.

The Average Time Spent on the Internet (H2)

A One-way ANOVA analysis suggested that there was a significant difference in daily average Internet use F(2,556) = 9.195; p = .000) based on participants’ marital or dating status. Post hoc analysis using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) method showed that single participants who were in a relationship were more frequent users of the Internet than married participants (MD = .8552; p = .000) and participants who were not in a relationship (MD = .723; p = .001). However, the time spent on the Internet between single participants who were and were not in a relationship (MD = .1319; p = .451) was not significantly different.

A two-way independent ANOVA was then performed to see whether an interaction effect was observed between gender and dating status in relation to the average Internet time. The result revealed no interaction between gender and dating status (F (2, 553) = .707, p = .494). There was a significant main effect of marital or dating status on the average time spent on the Internet (F (2,553) = 6.590, p = .001), but a main effect of gender on the daily average Internet time among single participants was not observed (F (1,553) = 3.784, p = .052), suggesting that marital status, and not gender, is the predictor of the time spent on the Internet. Thus H2 was supported.

The Engagement of Various Internet Activities (H3)

The third hypothesis examined whether single participants’ Internet activities were significantly associated with their well-being. The Pearson’s correlation analysis suggested no significant correlation between any of the Internet activities and single participants’ levels of life satisfaction and loneliness. The results did not change when dating status was examined (see Table 5), thereby suggesting that single participants’ various leisure activities on the Internet were not associated with their well-being. Hence, H3 was not supported.

A further analysis of data was undertaken to examine participants’ perceived online social support as a moderating variable between various Internet activities and loneliness or life satisfaction using Hayes process model. The results suggested that a moderation relationship could not be demonstrated between any of the Internet activities and loneliness or life satisfaction. Therefore, these results were omitted in an effort to keep the paper concise.

Marital Status, Gender, and Various Internet Activities

The different levels of engagement in various Internet activities based on participant gender and marital or dating status were explored. The result demonstrated that gender and marital status determined different levels of Internet use for fun seeking and accessing pornography. Using a two-way independent ANOVA test, no interaction effect between gender and marital status was observed for any Internet activity (see Table 6).

For fun seeking activities, the post hoc LSD analysis suggested that married participants were significantly less engaged in recreational online activities compared to their single-in-a-relationship (MD = −.336; p = .001) and single (MD = −.243; p = .004) counterparts. However, the scores between the two single groups were not significantly different (MD = −.093; p = .371).

With regard to accessing pornography, 39% of married participants reported never accessing online pornography, which was higher (24.6%) than single participants who were in a relationship and those (29.2%) who were not in a relationship. Single participants who were in a relationship (MD = .355; p = .000) and those who were not in a relationship (MD = .213; p = .005) were using pornography significantly more often than married participants. Moreover, males (F = 106.911; p = .000) were found to be more likely to access online pornography than females. The relative impact of gender (ηp2 = .162) was approximately five times stronger than that of marital status (ηp2 = .032), suggesting that gender is a stronger predictor than marital status in participants’ likelihood of accessing online pornography.

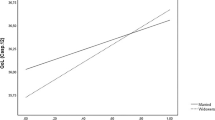

Comparative Profiles between Married and Single Participants

With regard to life satisfaction, a post hoc ANOVA analysis using the LSD method revealed that married participants scored significantly higher levels of life satisfaction (F = 14.043; p = .000) than single in a relationship participants (MD = 1.778; p = .004) and single participants (MD = 2.759; p = .000), while single and single in a relationship participants’ scores of life satisfaction were not significantly different (MD = .981; p = .129).

There was a significant relationship between marital or dating status and loneliness (F = .9.855; p = .000). Single participants scored significantly higher levels of loneliness compared with those who were dating (MD = 1.486; p = .003) and married (MD = 1.740; p = .000). There was no significant difference in the loneliness level between single in a relationship and married participants (MD = .254; p = .591). These findings suggested that dating might reduce loneliness for single participants, but does not increase life satisfaction (as was found among married participants).

Discussion

This study examined the role of the Internet as a resource for never-married people in Indonesia to promote or maintain their well-being. We believe that this is the first study that examines Internet use and well-being among single people. In general, we found that single people who were in a relationship used the Internet more than married and single people; however, their average Internet time did not influence their well-being.

Our first hypothesis focused on the contribution of online social support increasing never-married people’s life satisfaction and decreasing their loneliness. Although previous studies have demonstrated the merits of online social support (Chung 2013; Kim et al. 2011; Watkins and Jefferson 2013; Wellman and Haythornthwaite 2002), our study demonstrated that online social support is not associated with single people’s well-being. There are at least two arguments to explain the result.

Firstly, our finding may support the claim that support from real life contexts is required for online social support to be effective (Li et al. 2015). Ybarra et al. (2015) emphasized that online social support does not act as a substitute to offline social support, but as an adjunct. The relationship provided through the Internet has been argued to be artificial and less reliable (Leung and Lee 2005). Although these arguments were made in relation to Western samples, our findings suggest they may be applicable cross-culturally. This claim is further supported by a recent study in India, which indicated that online relationship establishment among young adults is commonly not built on trust and long-term expectation (Chakraborty 2019).

Secondly, the negative social stigma experienced by never-married people may increase their sense of social isolation and undermine any effect for online social support. The fear of social isolation has been found to diminish the perceived benefits of online social support (Lee and Cho 2018). Previous studies highlighted the social challenges of being single in Indonesia, where never-married people tend to withdraw socially in order to avoid embarrassment (Himawan 2019; Situmorang 2007; Tan 2010). Since singleness is perceived as socially unacceptable, some single people are more cautious and distant in their social relationships, and present themselves as resilient, independent and self-reliant when dealing with personal problems (Tan 2010).

The link between singleness and loneliness is supported by this study. Single individuals feel lonelier than married individuals and single individuals who are in a relationship. On the other hand, having a dating partner does not necessarily improve single peoples’ life satisfaction. This pattern is consistent with a previous study (Himawan 2019) about never-married people’s positive attitudes towards marriage. This finding might suggest that marriage tends to be seen as the only socially acceptable way to gain happiness or to be free from social pressures that potentially causes social withdrawal and loneliness. However, longitudinal studies are required to explore this proposition further.

With regard to the second hypothesis, single individuals who are in a relationship had the highest average Internet use time as compared to single and married participants. While studies on the relationship between Internet use and relationship status in Indonesia are scant, a growing body of research conducted in Western societies suggests that many dating people use the Internet with the intention of developing relationships (e.g. communicating between partners, and online dating) (Bellou 2015; Cacioppo et al. 2013). Single individuals who are dating might thus engage and develop their romantic relationships through social media. This study did not examine the reasons that single individuals who are in a relationship spent more time online than those who are not in a relationship. However, it is plausible that singles, assuming they have more freedom and flexibility as a result of no relationship commitment, might spend more time socializing offline. Still, this issue requires further investigation before any conclusion could be made.

The finding also suggests that never-married people accessed online pornography more than married people. This could be because married people do not solely rely on the Internet for sexual satisfaction, or it might also demonstrate a social desirability bias in participant responses since accessing pornography may be viewed as undesirable behavior among married individuals. Furthermore, pornography consumption is not associated with life satisfaction among never-married individuals. The finding could be justified by two arguments. Firstly, studies showed that despite immediate sexual gratification, pornography use has a counterproductive effect on individuals’ well-being and it may predict the development of mood problems (Cavaglion 2008; Grubbs et al. 2015). Secondly, there is a social taboo surrounding non-marital sexual activity (Hoesterey 2016), even in the online setting (Salna and Sipahutar 2017). This may create guilt about online sexual gratification. In Indonesia, both religious and cultural values are negotiated in the society in a way that engagement in pornography activity is not only considered an immoral practice, but also a sin (Himawan 2020b), which implies a stronger impact on an individual’s perceived guilt. The taboo nature of pornography appears to be quite common in many parts of Asia, particularly among those with cultures that consider discussion about sexuality as shameful and negative (Bennett 2000), such as, Malaysia (Shah 2018), Thailand, and Vietnam (Leesa-Nguansuk 2020). The taboo placed on sexual expression outside of marriage possibly explains the lack of published studies on pornography use and non-marital sexual practices in these countries. Marriage appears to be the only avenue for guilt free sexual activity (Himawan et al. 2018a).

Apart from marital status, gender has also been found to account for the use of Internet to access pornography. The analysis showed that men had higher online pornography use compared with women. The result concurs with previous studies (Albright 2008; Dufour et al. 2016) and supports the observation that gender is a meaningful predictor of the use of online pornography.

The limitations of the present study are as follows. There was no control for married participants’ satisfaction, which creates the possibility that those who participated in the study were happily married individuals and never-married participants where atypically unhappy. The fact that different numbers of males and females participated in the study may also have an impact on the generalizability of the findings as the study is weighted towards the experiences of single females. The study design was cross-sectional and thus has limited power in determining causal relationships between the measured variables. The impact of several demographic factors, such as age, religion, levels of education, and socio-economic background, were not considered in depth because of the unproportionate size of each class or group. Internet-based sampling might also bias the results as the study may have underrepresented less frequent Internet users. Lastly, it is possible that the rates of pornography use are underreported, given the social and moral sanctions applied to the use of pornography in Indonesia.

Conclusion and Direction for Future Studies

This study has demonstrated that single people’s well-being in Indonesia was not significantly associated with their Internet use and their perceived social support from online contexts. Given the preliminary nature of the study, these findings should be considered a foundation for larger, controlled studies. Further research should investigate different forms of online social support and how they interaction with offline social support. Future studies should take into account the intensity of Internet use in relation to an individual’s perceived social support (Ouyang et al. 2017), the quality of the marriage (in the case of married individuals), and should include a balanced sample of voluntary and involuntary singles. Future studies might also benefit from having equal proportions of single people across various demographic variables, such as age, gender, religion, and educational level, to allow sub-group analyses.

The practical implications of these findings are that the well-being of single Indonesians may be best improved through fostering face-to-face social interaction and through the reduction of stigma. Indonesian never-married individuals appear to be hesitant to seek support from others in overcoming personal problems (Tan 2010), which might cause them to be prone to experiencing loneliness. Therefore, strategic interventions may be best directed towards assisting singles to overcome this hesitancy. In Indonesian society, religion is a fundamental aspect of social identity (Himawan et al. 2018b) and there is an indication that some Indonesian single people tend to be more secure within their religious community (Himawan 2020b; Tan 2010). Hence, a practical intervention to reduce stigma and promote social connection would be for religious institutions to initiate programs, support groups, and social meetings for their never-married members to congregate on a regular basis. Various stigma reduction strategies through social campaigns might also improve the well-being of Indonesian single people who do not belong to any religious affiliation.

References

Adamczyk, K. (2017). Voluntary and involuntary singlehood and young adults’ mental health: An investigation of mediating role of romantic loneliness. Current Psychology, 36(4), 888–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9478-3.

Albright, J. M. (2008). Sex in America online: An exploration of sex, marital status, and sexual identity in internet sex seeking and its impacts. The Journal of Sex Research, 45(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490801987481.

Asosiasi Penyelenggara Jasa Internet Indonesia. (2018). Penetrasi & Profil Perilaku Pengguna Internet. https://apjii.or.id/content/read/39/410/Hasil-Survei-Penetrasi-dan-Perilaku-Pengguna-Internet-Indonesia-2018

Badan Pusat Statistik. (2010). Penduduk Indonesia: Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010. https://www.bps.go.id/website/pdf_publikasi/watermark%20_Dokumentasi%20Komprehensif%20SP%202010.pdf

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Bellou, A. (2015). The impact of internet diffusion on marriage rates: Evidence from the broadband market. Journal of Population Economics, 28, 265–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-014-0527-7.

Bennett, L. R. (2000). Sex talk, Indonesian youth and HIV/AIDS. Development Bulletin, 52, 54–57.

Cabañes, J. V. A., & Uy-Tioco, C. S. (2020). Mobile media and the rise of ‘glocal intimiacies’ in Asia. In J. V. A. Cabañes & C. S. Uy-Tioco (Eds.), Mobile media and social intimacies in Asia (pp. 1–12). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1790-6_1.

Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., Gonzaga, G. C., Ogburn, E. L., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2013). Marital satisfaction and break-ups differ across on-line and off-line meeting venues. Proceedings of the Naitonal Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(25), 10135–10140. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222447110.

Cavaglion, G. (2008). Cyber-porn dependence: Voices of distress in an Italian internet self-help community. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7(2), 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-008-9175-z.

Chakraborty, D. (2019). Components affecting intention to use online dating apps in India: A study conducted on smartphone users. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 15(3), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319510x19872596.

Chong, E. S., Zhang, Y., Mak, W. W., & Pang, I. H. (2015). Social media as social capital of LGB individuals in Hong Kong: Its relations with group membership, stigma, and mental well-being. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(1–2), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9699-2.

Chung, J. E. (2013). Social interaction in online support groups: Preference for online social interaction over offline social interaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1408–1414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.019.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155.

Darrington, J., Piercy, K. W., & Niehuis, S. (2005). The social and cultural construction of singlehood among young, single Mormons. The Qualitative Report, 10(4), 639–661.

DePaulo, B. M. (2013). Single in a society preoccupied with couples. In R. J. Coplan & J. C. Bowker (Eds.), The handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (pp. 302–316). John Wiley & Sons.

DePaulo, B. M., & Morris, W. L. (2005). Singles in society and in science. Psychological Inquiry, 16(2–3), 57–83.

DePaulo, B. M., & Morris, W. L. (2016). The unrecognized stereotyping and discrimination against singles. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 251–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00446.x.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Dufour, M., Brunelle, N., Tremblay, J., Leclerc, D., Cousineau, M. M., Khazaal, Y., Legare, A. A., Rousseau, M., & Berbiche, D. (2016). Gender difference in internet use and internet problems among Quebec high school students. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(10), 663–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716640755.

Erikson, E. (1997). The life cycle completed (Vol. extended version/ with the new chapters on the ninth stage of development by Joan M. Erikson). W. W. Norton.

Fachrudin, F. (2016). Ketentuan soal perzinahan dalam KUHP dinilai perlu diperluas. Kompas. http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2016/09/08/18302141/ketentuan.soal.perzinahan.dalam.kuhp.dinilai.perlu.diperluas

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149.

Grubbs, J. B., Stauner, N., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., & Lindberg, M. J. (2015). Perceived addiction to Internet pornography and psychological distress: Examining relationships concurrently and over time. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(4), 1056–1067. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000114.

Hamburger, Y. A., & Ben-Artzi, E. (2000). The relationship between extraversion and neuroticism and the different uses of the Internet. Computers in Human Behavior, 16(4), 441–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0747-5632(00)00017-0.

Hays, R. D., & DiMatteo, M. R. (1987). A short-form measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6.

Himawan, K. K. (2019). Either I do or I must: An exploration of the marriage attitudes of Indonesian singles. The Social Science Journal, 56(2), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2018.07.007.

Himawan, K. K. (2020a). The Single’s struggle: Discovering the experience of involuntary singleness through gender and religious perspectives in Indonesia. The Family Journal, 28(4), 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480720950419.

Himawan, K. K. (2020b). Singleness, sex, and spirituality: How religion affects the experience of being single in Indonesia. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(2), 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2020.1767555.

Himawan, K. K., Bambling, M., & Edirippulige, S. (2018a). The Asian single profiles: Discovering many faces of never married adults in Asia. Journal of Family Issues, 39(14), 3667–3689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x18789205.

Himawan, K. K., Bambling, M., & Edirippulige, S. (2018b). Singleness, religiosity, and the implications for counselors: The Indonesian case. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 14(2), 485–497. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v14i2.1530.

Himawan, K. K., Bambling, M., & Edirippulige, S. (2018c). What does it mean to be single in Indonesia? Religiosity, social stigma, and marital status among never-married Indonesian adults. SAGE Open, 8(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018803132.

Himawan, K. K., Bambling, M., & Edirippulige, S. (2019a). Modernization and singlehood in Indonesia: Psychological and social impacts. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 40, 499–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2017.09.008.

Himawan, K. K., Bambling, M., Edirippulige, S., & Underwood, M. (2019b). Examining the mental health, the reasons, and the coping strategies of individuals remaining single in Indonesia the 9th International Conference of Health, Wellness, and Society, University of California Berkeley, San Francisco, CA.

Hoesterey, J. B. (2016). Vicissitudes of vision: Piety, pornography, and shaming the state in Indonesia. Visual Anthropology Review, 32(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12105.

Jones, G. W. (2007). Delayed marriage and very low fertility in Pacific Asia. Population and Development Review, 33(3), 453-478.

Jones, G. W. (2010). Changing marriage patterns in Asia. A. R. Institute. http://www.ari.nus.edu.sg/wps/wps10_131.pdf

Jones, G. W. (2018). Changing marriage patterns in Asia. In Z. Zhao & A. C. Hayes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of Asian demography (pp. 351–369). Routledge.

Kim, Y., Sohn, D., & Choi, S. M. (2011). Cultural difference in motivations for using social network sites: A comparative study of American and Korean college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(1), 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.08.015.

Kluver, R., & Cheong, P. H. (2007). Technological modernization, the internet, and religion in Singapore. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12, 1122–1142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00366.x.

Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Johnson, B. K., & Westerwick, A. (2013). To your health: Self-regulation of health behavior through selective exposure to online health messages. Journal of Communication, 63, 807–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12055.

Lachmann, B., Sariyska, R., Kannen, C., Cooper, A., & Montag, C. (2016). Life satisfaction and problematic Internet use: Evidence for gender specific effects. Psychiatry Research, 238, 363–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.017.

LaCoursiere, S. P. (2001). A theory of online social support. Advances in Nursing Science, 24(1), 60–77. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-200109000-00008.

Lee, E. J., & Cho, E. (2018). When using Facebook to avoid isolation reduces perceived social support. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 21(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0602.

Leesa-Nguansuk, S. (2020). Thailand’s internet censorship rates 6/10. Bangkok Post. https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/1837434/thailands-internet-censorship-rates-6-10

Leung, L., & Lee, P. S. N. (2005). Multiple determinants of life quality: The roles of Internet activities, use of new media, social support, and leisure activities. Telematics and Informatics, 22(3), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2004.04.003.

Li, X., Chen, W., & Popiel, P. (2015). What happens on Facebook stays on Facebook? The implications of Facebook interaction for perceived, receiving, and giving social support. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.066.

Malcolm, M., & Naufal, G. (2014). Are pornography and marriage substitutes for young men? (8679). http://ftp.iza.org/dp8679.pdf

Manning, J. C. (2006). The impact of internet pornography on marriage and the family: A review of the research. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 13(2–3), 131–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720160600870711.

Mazzoni, E., Baiocco, L., Cannata, D., & Dimas, I. (2016). Is internet the cherry on top or a crutch? Offline social support as moderator of the outcomes of online social support on problematic Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 56, 369–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.032.

Mesheriokova, V., & Tebb, K. (2016). Effect of an iPad-based intervention on sexual health knowledge and intentions for contraceptive use among adolescent females at a school-based health center. Poster Abstracts, 58, S63–S85.

Moon, J. Y. (2020). The digital wash place: Mobile messaging apps as new communal spaces for Korean ‘Smart Ajummas. In J. V. A. Cabañes & C. S. Uy-Tioco (Eds.), Mobile media and social identities in Asia. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1790-6_5.

Morris, W. L., Sinclair, S., & DePaulo, B. M. (2016). No shelter for singles: The perceived legitimacy of marital status discrimination. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 10(4), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430207081535.

Odacı, H., & Çıkrıkçı, Ö. (2014). Problematic internet use in terms of gender, attachment styles and subjective well-being in university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.11.019.

Odacı, H., & Kalkan, M. (2010). Problematic internet use, loneliness and dating anxiety among young adult university students. Computers & Education, 55(3), 1091–1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.006.

Ouyang, Z., Wang, Y., & Yu, H. (2017). Internet use in young adult males: From the perspective of pursuing well-being. Current Psychology, 36, 840–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9473-8.

Phua, V. C., & Moody, K. P. (2018). Online dating in Singapore: The desire to have children. Sexuality & Culture, 23(2), 494–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9571-x.

Pinquart, M. (2016). Loneliness in married, widowed, divorced, and never-married older adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 20(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075030201002.

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42(3), 290–294. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11.

Salna, K., & Sipahutar, T. (2017). Block porn or be blocked, Indonesia warns Google, Twitter. http://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2017/11/18/block-porn-or-be-blocked-indonesia-warns-google-twitter.html

Schlarb, A. A., & Brandhorst, I. (2012). Mini-KiSS online: An Internet-based intervention program for parents of young children with sleep problems - influence on parental behavior and children's sleep. Nature and Science of Sleep, 4, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S28337.

Schou Andreassen, C., Billieux, J., Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Demetrovics, Z., Mazzoni, E., & Pallesen, S. (2016). The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160.

Shah, A. (2018). Police will know if you watch porn. New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/news/exclusive/2018/07/388926/exclusive-police-will-know-if-you-watch-porn

Shaw, L. H., & Gant, L. M. (2002). In defense of the Internet: The relationship between internet communication and depression, loneliness, self-esteem, and perceived social support. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 5(2), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493102753770552.

Situmorang, A. (2007). Staying single in a married world. Asian Population Studies, 3(3), 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730701746433.

Slonim, G., Gur-Yaish, N., & Katz, R. (2015). By choice or by circumstance?: Stereotypes of and feelings about single people. Studia Psychologica, 57(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.21909/sp.2015.01.672.

Tan, J. E. (2010). Social relationships in the modern age: Never-married women in Bangkok, Jakarta, and Manila. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 41(5), 749–765.

Wang, H., & Abbott, D. A. (2013). Waiting for Mr. Right: The meaning of being a single educated Chinese female over 30 in Beijing and Guangzhou. Women’s Studies International Forum, 40, 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2013.08.004.

Wang, E. S., & Wang, M. C. (2013). Social support and social interaction ties on internet addiction: Integrating online and offline contexts. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16(11), 843–849. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0557.

Watkins, D. C., & Jefferson, S. O. (2013). Recommendations for the use of online social support for African American men. Psychological Services, 10(3), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027904.

Wellman, B., & Haythornthwaite, C. (2002). The internet in everyday life. Wiley., 2, 447–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X16659019.

Ybarra, M. I., Mitchell, K. J., Palmer, N. A., & Reisner, S. L. (2015). Online social support as a buffer against online and offline peer and sexual victimization among U.S. LGBT and non-LGBT youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 39, 123–136. https://doi.org/j.chiabu.2014.08.006

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Leonce Newby for her helpful assistance in proofreading the manuscript, and Julian Halim for his assistance in the back-translation process of the study instruments.

Funding

This work was supported by Indonesian Endowment Funds for Education. The first author was the recipient.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

Ethical Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Queensland Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: 2017000826) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Himawan, K.K., Underwood, M., Bambling, M. et al. Being single when marriage is the norm: Internet use and the well-being of never-married adults in Indonesia. Curr Psychol 41, 8850–8861 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01367-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01367-6