Abstract

Self-compassion research has relied heavily on self-report measures; less is known about its role in self-directed thoughts during challenging or stressful situations. A vignette measure portraying difficult hypothetical situations was developed to examine emerging adults’ self-directed thoughts, with a focus on identifying compassionate and uncompassionate thoughts of different kinds. An MTurk sample (N = 103) was used for the development of the vignette measure, and an undergraduate sample (N = 478) was used to assess its application. Participant responses were coded based on perceived function, resulting in 29 categories. Overall, thoughts that conveyed a lack of compassion were more common than compassionate thoughts. Factor analysis yielded six- and five-factor solutions for failure- and rejection-based vignettes, respectively. Three factors were common to both contexts: (1) Strong Negative responses included self-judgment and alienation; (2) Positive responses included self-encouragement, self-care, social reasoning and problem-solving; and (3) Externalizing responses involved blaming or devaluing people or activities. Component scores for the first two factors generally were associated with self-reported shame, self-criticism, self-esteem and self-compassion in the expected directions. In contrast, Externalization was inversely associated with guilt. Observation and conceptual categorization of self-compassionate and uncompassionate thoughts complements and informs questionnaire-based research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For more than fifteen years, Germer (2009), Gilbert (2009), and Neff (2003b) have captured compassionate elements of Buddhist philosophy and articulated them in a way conducive to use, observation, and study using Western psychological principles. Empirical work to date has revealed encouraging results pointing to the apparent benefits of self-directed compassion in several domains (see Barnard & Curry, 2011, for a review). It consistently has been related to lower levels of psychopathology (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012), positive affect (Leary, Tate, Adams, Allen, & Hancock, 2007), higher emotional intelligence, coping, and stability (Neff, 2003b), more health-promoting and pro-social behaviours (see Neff, 2012 for a review), and feelings of well-being and life-satisfaction (Neely, Shallert, Mohammed, Roberts, & Chen, 2009; Neff, 2003a).

Self-directed compassion involves relating to the self in a compassionate manner, in the same way that one would relate to others compassionately. In North American society, the idea of relating kindly to oneself is fairly novel; however, Buddhist philosophy has long recognized the importance of compassion directed inwards (Buddhaghosa, 1975; Neff, 2003a). At their core, definitions of compassion share a focus on loving-kindness and the desire to help alleviate another’s suffering (Germer, 2009; Gilbert, 2009; Neff, 2003b). Some researchers emphasize mindful awareness as a component of, or a necessary requirement for, self-compassion (Gilbert, 2009; Neff, 2003b; see also Germer, 2009); Neff’s definition also includes recognition of suffering as a shared human experience. Care has been taken to distinguish self-directed compassion from self-pity and passive self-indulgence (Germer & Neff, 2013; Neff, 2003a, b). Likewise, although self-directed compassion and self-esteem measures typically are correlated, self-esteem has ties to performance-based self-evaluation and social comparison, rather than nonjudgmental acceptance of oneself within the context of the human condition (Neff, 2003a, 2003b; Neff & Vonk, 2009). Furthermore, self-compassion has been reliably, inversely related to shame and self-criticism (Barnard & Curry, 2011; Costa, Marôco, Pinto-Gouvei, Ferreira, & Castilho, 2016; López et al., 2015; Neff, 2003a).

There is debate in the literature regarding the conceptualization of the inverse of self-compassion. The widely used Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, 2003b) includes three negative subscales: self-judgment (the inverse of self-kindness), isolation (the inverse of common humanity), and over-identification (the inverse of mindfulness). Higher scores on these subscales are thought to indicate lower levels of self-compassion (Neff, 2003b). This perspective informed the coding in the current study, and therefore uncompassionate thoughts were operationalized as thoughts reflecting self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification. However, we acknowledge that the theory and research behind the concept of self-compassion (and uncompassion) is evolving (e.g., see Muris, Otgaar, & Pfattheicher, 2019, or Pfattheicher, Geiger, Hartung, Weiss, & Schindler, 2017, for alternative perspectives).

The recent proliferation of research on self-directed compassion (Neff, 2015; Neff & Dahm, 2014) has been facilitated, but also limited, by widespread reliance on the Self-Compassion Scale as a single self-report measure (SCS; Neff, 2003a). Its use in disparate populations has generated substantial data with which to evaluate its reliability and factorial validity (Neff et al., 2019), and researchers’ adoption of a common instrument facilitates comparison across studies; however, broadening our understanding of self-compassion as a construct requires examining it in divergent, complementary ways (Falconer, King, & Brewin, 2015; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012; Neff, 2003a; Neff, 2015; Williams, Dalgleish, Karl, & Kuyken, 2014). Reliance on a questionnaire-based measure of self-compassion arguably has influenced our conceptualization of the construct, such that we think of it more as a trait-like characteristic rather than a process that occurs within individuals in real time (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012; Neff, 2015).

Although there are limits to our capacity to observe self-directed compassion as an internal process, some qualitative researchers have interviewed people about their self-compassionate experiences and thoughts: either in general (Campion & Glover, 2017), or in a specific domain, such as self-perception of their body (Berry, Kowalski, Ferguson, & Mchugh, 2010; Sutherland et al., 2014b; Woekel & Ebbeck, 2013). Others have interviewed participants about how they experienced self-compassion and mindfulness-based interventions (Köhle et al., 2017; L’Estrange, Timulak, Kinsella, & D’Alton, 2016). This research adds to our understanding of what self-compassionate thoughts and ideas might look like through a retrospective lens.

A pioneering study demonstrated the potential to examine spontaneously arising speech for self-directed compassion. Observing that comments posted by internet users recovering from self-injury contained self-compassionate content, Sutherland, Dawczyk, et al. (2014a) differentiated themes and related them to Neff’s (2003a) proposed components of self-compassion. They considered self-kindness to be reflected in comments that conveyed self-understanding and warmth toward oneself, acknowledged strength and recovery, described self-caring behaviour, and portrayed themselves as more than simply someone who self-injures. In contrast, an understanding of common humanity (shared human experience) was shown in comments about receiving or feeling compassion from or for others, normalizing self-injury, opposing judgment, and being seen and understood by others. Statements considered to exemplify mindfulness conveyed a balanced perspective, acceptance of experiences, distress as manageable, and hope. These themes were found in content that likely was written after personal reflection and thoughtful deliberation by people who developed the strength to overcome a personal struggle.

As yet unknown, however, are the frequency and content of compassionate self-directed thoughts as they arise in everyday life. Relating compassionately to oneself is thought to be particularly beneficial when responding to difficult and stress-inducing experiences, as it buffers individuals from some of the negative emotions associated with such experiences (Blackie & Kocovski, 2019; Leary et al., 2007; Terry, Leary, & Mehta, 2013). We developed a vignette-based measure to inquire about immediate thoughts arising in response to difficult situations that participants might be expected to encounter in their everyday lives. Our goal was to code these self-directed thoughts to determine how often they were compassionate, to observe what compassionate self-talk looked like within our sample, and to situate compassionate (and un-compassionate) thoughts within the full, broad range of responses that the hypothetical scenarios engendered. Use of a variety of vignettes allowed for investigation of self-directed compassion at a situation-specific, rather than generalized and trait-like, level.

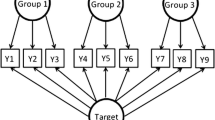

Our research strategy entailed developing a broad range of content codes using a relatively diverse sample of emerging adults from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk; i.e., the ‘development’ sample), and then applying the coding system to a second sample of university students (i.e., the ‘application’ sample). Whereas diversity in the development sample was intended to elicit a wide range of potential responses to the vignettes, the application sample was limited to university students to specify the population to which findings would apply. The mental health crisis among students at North American universities necessitates continued study of self-directed compassion within this population, given its strong association with mental health (Macbeth & Gumley, 2012). According to the American College Health Association (2017), 52.7% of university students reported feeling hopeless within a one-year period, 39.1% felt so depressed it was difficult to function, and 61.9% felt overwhelming anxiety. Although young people have reported less self-directed compassion than more mature populations (Neff & Vonk, 2009), self-compassion has been associated with beneficial outcomes among university students (Arslan, 2016; Breines et al., 2015; Iskender, 2009; Neff & McGehee, 2010; Sharma & Davidson, 2015; Sirois, 2015; Yamaguchi, Kim, & Akutsu, 2014).

We sought to describe the range and relative frequency of self-directed compassionate and uncompassionate thoughts that may be generated by university students in difficult moments. Furthermore, we used exploratory factor analysis to describe how content categories tended to co-occur, and related these category groupings to constructs of shame, self-criticism, self-esteem, and self-compassion, to get a better idea of their function (guilt was included for purposes of discriminant validity, since it has not been associated with self-directed compassion; Fisher & Exline, 2010). This systematic exploration was intended to complement and inform questionnaire-based research.

Method

Participants

Development Sample

The sample used for initial development of content codes was recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). MTurk samples have proven to be relatively demographically diverse, and obtained data are at least as reliable as from more traditional samples (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011). Although 178 participants initially opened the survey, 75 were excluded for completing less than 50% of items, leaving a final N of 103. Included participants were 24 years old on average (range from 18 to 35 years; SD = 2.94). Sixty-three (61.2%) participants identified as White/European, 10 (9.7%), as Black/African/Caribbean, 6 (5.8%) as Southeast Asian, 14 (13.6%) as South Asian, 7 (6.8%) as Latin American, and 3 (2.9%) as “other.” Regarding gender, 41 (39.8%) participants identified as female, 59 (57.2%) male, and 3 (2.9%) non-binary, transgender, or undisclosed.

Application Sample

A total of 586 undergraduate students participated in exchange for credit toward an introductory psychology course. Of the total sample, data from 107 participants ultimately were excluded from factor analyses because they provided less than 12 codeable responses (i.e., less than one response per vignette) along with one outlier (response frequency > 3 SD above the mean). The mean age of remaining participants (N = 478) was 18.88 years (range 16–36 years; SD = 1.26). The majority (369; 77.2%) participants identified as White/European, 29 (6.1%) as Southeast Asian, 29 (6.1%) as South Asian, 15 (3.1%) as Black/African/Caribbean, 6 (1.3%) as Arab, 6 (1.3%) as Latin American, 5 (1%) as West Asian, and 1 (0.2%) as Aboriginal/First Nations/Métis, and 18 (3.8%) as “other.” Regarding gender, 342 (71.5%) participants identified as female, 133 (27.8%) as male (28.5%), and 3 (0.6%) as agender or genderless.

Materials

Vignettes

Twenty-four illustrated scenarios were created to evoke compassionate (or uncompassionate) responses (see Figs. 1 and 2 for examples).Footnote 1 Each scenario portrayed a difficult event that emerging adults typically might experience. The vignettes were accompanied by illustrations to increase their engagement with the scenarios, in order to facilitate access to relevant automatic thoughts. We attempted to cover a broad range of difficult experiences (e.g., at school, during leisure activities, and in social situations; involving romantic partners, friends, teammates, etc.). Items could be grouped into three broader content domains: achievement (7 items), social rejection (10 items), and social transgressions (4 items; the content of other remaining items contained elements of more than one domain). For the development sample, responses to all 24 vignettes were qualitatively coded and organized. For the application sample, we identified six vignettes in each of two domains, social rejection and failure, selecting a variety of exemplars within each context.

Vignettes were presented individually and in random order; no time limit was imposed. Participants were provided with images that matched their specified gender (including an androgynous character for participants who indicated their gender as neither female nor male). Participants were given the following instructions: “For the following scenarios, we ask that you please tell us what your automatic thoughts would be in the given situations. We are looking for phrases or statements that describe your thoughts, not individual words like ‘good’ or ‘ok’ or a single emotion word.” Participants were asked for three thoughts per vignette, and a codeable thought could range from a two-word phrase to one multiple phrase sentence, with an average of 16.6 words per participant per vignette (with a mean of approximately six words per response).

The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003a). The SCS is a 26-item scale that evaluates the three components of self-compassion through six subscales: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, mindfulness, isolation, and over-identification. Using a 5-point Likert scale, participants rate the frequency with which they respond to difficult circumstances according to these domains. Higher scores indicate greater self-compassion. The SCS has been demonstrated to have a high degree of validity and reliability (e.g., Castilho, Pinto, & Duarte, 2015; Neff, 2003a). In the application sample of the current study, internal consistency was as follows: Cronbach’s α = .72 for Mindfulness, .73 for Over-Identification, .84 for Self-Kindness, .81 for Self-Judgment, .78 for Common Humanity, and .77 for Isolation.

Test of Self-Conscious Affect for Adolescents (TOSCA-A; Tangney, Wagner, Gavlas, & Gramzow, 1991). This widely used scale includes ten negative and five positive vignettes of difficult situations. For each vignette, participants rate the likelihood they would respond four different ways on a 5-point Likert scale. Validity was supported by expected relations between the subscales and empathy (associated with shame-free guilt), and anger (associated with shame; Tangney et al., 1991). Subscales reflecting shame and guilt (each 15 items) were used in the current study. In the application sample of the current study, internal consistency was as follows: Cronbach’s α = .82 for Shame, and .84 for Guilt.

Level of Self-Criticism (LOSC) scale (Thompson & Zuroff, 2004). This 22-item self-report scale measures two forms of negative self-evaluation: Comparative Self-Criticism (SCS) and Internalized Self-Criticism (ISC) using a 7-point Likert scale. It has demonstrated good convergent validity (Thompson & Zuroff, 2004). In the application sample of the current study, internal consistency was Cronbach’s α =.78 for CSC and .88 for ISC.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (SES; Rosenberg, 1965)

This widely used 10-item self-report scale, uses a 4-point Likert scale to assess positive and negative feelings about the self in order to measure global self-worth. In the application sample of the current study, Cronbach’s α = .91.

Procedures

Development Sample

Participants were recruited through MTurk. After reading a brief description of the study, those who proceeded provided informed consent and were linked to the study housed on Qualtrics online survey software. In a single session (approximately one hour), participants completed a brief demographics questionnaire, responded to the vignettes, and completed several questionnaires (the latter as part of an unpublished dissertation study; Redden, 2019). They completed vignettes before questionnaires to avoid influencing vignette responses. Participants were compensated $0.75 USD for completing the study.

Qualitative Analytic Approach

A team composed of a faculty advisor, a graduate student, and three fourth-year undergraduate research interns was assembled to identify content codes. It was imperative to the process to include undergraduate team members because, as emerging adults, they provided perspective on the function of vignette responses for their cohort. For several months, the research team met weekly for approximately three hours to discuss responses and look for patterns. Taking a complete coding approach (see Braun & Clarke, 2013), we sorted all responses into categories, grouping together those that appeared to serve a similar function. Responses were not grouped based simply on wording; rather, we considered the context surrounding each response and inferred its most likely function. We assigned these initial categories temporary placeholder names (e.g., “guilt,” “questioning,” “self-care,” etc.). These categories evolved as additional data were added. For example, categories were broadened to encompass similar but non-redundant responses, or split when multiple, fairly coherent sub-themes were identified within a category. Additional categories were generated when we noticed a recurring theme in the data that did not fit the pre-existing categories. Considerable attention also was given to capturing the intended meaning of subtle nuances in language within this population. To ensure the correct interpretation of age-relevant colloquialisms, the research team would occasionally consult external sources such as online resources and young adults unrelated to the research project.

For approximately a quarter of the dataset, responses were categorized by the team; we then progressed to coding independently. Responses not clearly fitting into a category were discussed during weekly team meetings to consider multiple perspectives on how best to categorize them. A proportion of thoughts were deemed uncodeable (as described below). Each categorized thought was entered into a shared online document, which was reviewed frequently to ensure consistency.

In the next developmental phase, we considered how categories related to self-compassion theory. We re-named the response categories to capture the coding team’s interpretations of implicit meanings in the data. For example, a response such as “Someday this will be a funny story” would have originally been placed in a “positive thinking” category. Subsequently, we used our interpretive lens to name this category “self-encouragement” under the superordinate category, “self-kindness.” Thus, category labels reflected theory rather than terms used by participants.

Application Sample

Participants were recruited through the university’s undergraduate participant pool. Informed consent procedures and Qualtrics survey composition were essentially identical to the development sample.

Applying the Coding System

Four new undergraduate coders, trained by the original team, received approximately nine hours of training on theory, the specific content codes, and practice coding responses together as a group. They referred to the exhaustive coding manual and passed a test with at least 70% agreement before proceeding. For three months, challenging items were discussed during weekly three-hour team meetings (including the faculty advisor, graduate student, and original long-term undergraduate coders). They were encouraged to code individually only those items that they could code with certainty. All challenging responses were recorded for future reference (however this list was unavailable during reliability coding). Codes were recorded using NVivo software.

Results

Development Sample: Qualitative Analysis

Our iterative coding process ultimately resulted in 29 content categories (see Table 7 in Appendix 1 for detailed descriptions and examples of each category). There were three observed forms of self-kindness: (a) making self-encouraging statements, (b) expressing liking or fondness for oneself, and (c) proposing self-care activities. Three other categories appeared to characterize mindful acceptance: (a) accepting personal limitations, often in the form of acknowledging a personal shortcoming without over-identifying with it, (b) accepting experience, such as labelling the unpleasant experience while tolerating or welcoming it, and (c) accepting personal responsibility, by recognizing one’s role in creating the situation. Common humanity was observed as (a) taking another’s perspective in difficult situation, (b) wishing others well, and (c) normalizing or generalizing to human experience.

Three conceptual opposites of self-compassion, proposed by Neff (2003a), are self-judgment, over-identification, and isolation. Two categories appeared to serve the function of self-judgment as they portrayed unnecessary punitive or derogatory thoughts towards oneself without a constructive focus. These were (a) unequivocal, broadly self-critical statements or (b) annoyance or critical feelings toward oneself. Seven categories conceptually appeared to exemplify over-identification: (a) grasping, or wanting things to be different than they were; (b) choosing to avoid unpleasant experiences or feelings through behaviours such as drinking or sleeping; (c) avoidant devaluing, denigrating or dismissing something or someone; (d) self-protective externalizing, assigning responsibility for a problem to someone or something else; (e) directed hostility, verbal aggression toward something or someone; (f) catastrophizing, irrationally inferring terrible consequences, and (g) a catch-all category, termed “other over-identification,” that included a variety of thoughts that functionally would hinder mental flexibility or curiosity (e.g., “I hate this,” or “I can’t do this at all.”). Isolation was exemplified in three distinct ways: (a) a general sense of isolation and being alone in one’s experience, (b) focusing on oneself as a (solitary or unique) victim, and (c) narcissism, assuming superiority over others.Footnote 2

In addition, some inverse categories did not readily fit into a discrete theorized facet of self-compassion. The category “Fear of Others’ Reactions,” which encompasses fears, worry, or anxiety associated with the anticipation of others’ reactions, appeared to involve both over-identification and isolation. Similarly, the category “Pressure to Achieve” appeared to reflect both over-identification and self-judgment. A third category was developed that reflected elements of Isolation and Self-Judgment, which was Internalization of Others’ Judgment.

Several response categories did not appear to be overtly compassionate or uncompassionate. We grouped reasoning, information seeking, and problem-solving together in an overarching category called “Reasoning,” as all three were logical, pragmatic responses. Responses assigned to the reasoning category differed depending on the type of vignette: in response to rejection, they usually involved social reasoning. We made no assumptions about association of these categories with self-compassion. An additional category, venting, captured brief displays of intense emotion that functioned to release one’s initial frustration; these displays were not directed at a specific target.

A final and frequent category, “acknowledging experience,” involved statements about emotions participants were feeling. Although these responses could indicate mindful awareness of emotional state, we lacked sufficient evidence to discern whether people were mindfully aware of, versus caught up with, or carried away by, their perceived emotions. Thus, this category likely was heterogeneous with respect to whether it served a compassionate function.

Application Sample: Replication and Quantitative Analysis

In total, 95.85% (14,438) of participant responses could be assigned a category. The remainder were deemed uncodeable for the following reasons: misinterpretations of the vignette, ambiguous wording that could justify two categories contradictory in nature, thoughts intended to be humorous (since humour can serve different functions), and single-word responses with insufficient context to interpret the function. Table 1 provides frequencies as a function of vignette type (expressed as a proportion of total responses for response categories). The type of adverse experience (failure versus social rejection) elicited proportionately different responses. The three most common codes in response to failure vignettes were problem-solving, grasping, and pressure to achieve, whereas the most common codes for social rejection were information seeking, acknowledging experience, and (social) reasoning. Across vignette types, only a small proportion of responses appeared to serve the function of self-kindness, mindful awareness, or common humanity (14.3% for failure, 7.3% for rejection). Self-encouragement was the most frequently observed compassionate category, followed by acceptance of personal limitations. Most of the remaining compassionate categories, including all with a common humanity theme, were rare (less than 1%); in comparison, particularly uncompassionate categories tended to occur more often (e.g., for failure and rejection, respectively: self-judgment 4 and 3.7%, isolation 1.8 and 6.6%).

Inter-rater reliability for each response category was calculated on 20% of vignettes completed by the application sample using two-way mixed effects intra-class correlations (see Table 1). Reliability was calculated separately for failure and social rejection vignettes, since vignette type was associated with subtle content-related differences in some response categories that impacted coding. Four reliability coders each were randomly assigned 5% of the sample. Inter-rater reliability was calculated for categories observed with sufficient frequency to support their estimation (i.e., allowing for sufficient response variability to detect reliability; Goodwin & Leech, 2006; Shoukri, Asyali, & Donner, 2004): our liberal cut-off was 1 % of total codeable responses, which eliminated nine categories in each of the failure and social rejection domains. According to frequently cited guidelines (Cicchetti, 1994), 38 of the 54 intra-class correlations for specific categories were high enough to be considered excellent (> .75), 11 were good (between .60 and .74), three were fair (between .40 and .59), and two were poor (<.39). Those with poor and fair reliability were observed fairly infrequently, thus lower variability likely limited the strength of reliability estimates (Goodwin & Leech, 2006).

Exploratory Factor Analyses

Participants’ frequency of responses in each category were subjected to factor analysis. All analyses were conducted using the most recent version of R (R Core Team, 2019). Any response category with frequency lower than 1 %, or an intra-class correlation coefficient less than .69, was excluded from analysis. In addition, participants who provided fewer than 12 responses (and one outlier with responses > 3SD above the mean) were excluded from analysis.

A number of principal components analyses were conducted to guide the authors in their delineation of common types of responding. In the case of responses to the failure vignettes, it was determined that a six-component solution, with some degree of cross-loading on similar components, was the best solution. In the case of the rejection vignettes, it was concluded that a five-component solution, again with some degree of cross-loading on similar components, was the best solution. In both cases, the solutions were obtained under varimax rotation, followed the Kaiser criterion (Kaiser, 1958), and were distinguishable using parallel analysis (see Fabrigar & Wegener, 2012). Solutions accounted for 47 and 45% of the total variance for failure and rejection, respectively; each of the factors accounted for 7 to 10% of the variance after rotation. Please see Tables 2 and 3 for the solutions. As can be seen from the tables, there are pronounced similarities between the two solutions, though there are some differences that likely are attributable to the nature of the vignettes. Factors were assigned labels that were relatively theory-neutral to avoid over-interpretation.

Three factors were identified across both failure and social rejection contexts. (1) A factor termed “Strong Negative Responses” included self-judgment and seeing the self as a victim; catastrophizing and general overidentification (e.g., “I hate this,” “I can’t do this”; for failure); and self-isolation (for social rejection). This collection of responses appeared unequivocally unsupportive of the self, and self-regulation. (2) A factor termed “Positive Responses” included encouragement and problem-solving, self-care (for failure), and reasoning (for social rejection). Thus, it included some responses seen as self-directed compassion, and some solution-oriented responses. In response to failure, acknowledgment of the experience loaded inversely on this factor, whereas in response to rejection, a mild form of self-judgment loaded inversely. (3) An “Externalization” factor included blaming others, overt hostility toward others (for social rejection), and devaluing people or activities. This factor appeared to capture an uncompassionate focus on others.

Other factors were identified in only one context. In response to failure, three such factors were identified: “Situation-Specific Shame” (F4) consisted of avoidance, fear of others’ reaction, and feelings of isolation; and “Non-Acceptance” (F5) involved wishing for, and asking questions about, how to achieve a different outcome (accepting personal limitations loaded inversely). A final factor was termed “Tension Release” (F6): venting (e.g., swearing), a response that would serve to release pressure, loaded highly, whereas increased pressure to succeed loaded inversely. The two additional social rejection factors were “Self Protection” (R4), which included recognition of one’s emotional response to the rejection, coupled with problem-solving and plans to avoid the experience (seeking information loaded inversely), and “Accepting Social Limitations” (R5), which included accepting personal limitations and negative implications about the self (pressure to achieve loaded inversely).

Correlations of Response Types Across Vignette Types

Component scores were generated for the six components for failure and the five components for rejection. Table 4 shows the correlations across vignette types for the response component scores. Confidence intervals (95%) are also given. Given that a varimax (i.e., orthogonal) rotation was applied, the correlations amongst the components for failure and amongst the components for rejection were essentially zero. As can be seen in the table, CI’s for these correlations ranged from negligible to medium in magnitude. In particular, the CI for the correlation between Strong Negative responses in failure and rejection contexts corresponded to a medium effect size, as did the CI for the correlation involving Positive responses. However, Positive and Negative responses were more modestly, inversely related across contexts (CI’s consistent with a negligible to small association). The CI for the correlation for Externalization across contexts ranged from small to medium in size. A few other correlations with CI’s ranging from small to medium effects were theoretically consistent. For example, Externalization (to failure) was inversely associated with Self Protection, and Externalization (to rejection) was directly associated with Tension Release. Notably, Situation-Specific Shame (to failure) was not meaningfully associated with Strong Negative Response (to rejection).

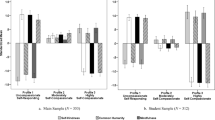

Correlations between Response Types and Validation Measures

Table 5 provides intercorrelations among questionnaire measures measuring related constructs, and Table 6 provides correlations between these questionnaires and response component scores.Footnote 3Footnote 4 As seen in the table, Positive Responses to rejection scenarios were moderately associated with shame, self-criticism, self-esteem, and self-compassion in theoretically expected directions, with CI’s for correlations ranging from small to medium effects; however, these correlations were somewhat attenuated for Positive Responses to failure vignettes (range from negligible to moderate effects). Strong Negative Responses to failure and rejection were moderately associated with self-reported shame, self-criticism, self-esteem, and self-compassion, with CI’s for correlations generally ranging from small to medium effects. In contrast, Situation-Specific Shame (to failure) was less strongly associated with these measures, with CI’s for correlations ranging from negligible to moderate effect sizes. Externalizing was fairly negligibly associated with these measures. However, unlike most other factors, Externalizing was inversely associated with guilt, particularly in the rejection context (CI consistent with a small to medium effect).

Discussion

What Did Self-Directed Compassion Sound like?

In this study we reviewed university students’ immediate responses to a variety of difficult hypothetical situations, with the goal of identifying thoughts that appeared compassionate and uncompassionate toward the self. We also sought to situate these thoughts within the full, broad range of responses that such scenarios engendered. Since our inner thought processes are verbally mediated, any theory centred on relating to the self is supported by a foundational understanding of what people are actually saying to themselves. Thus, the current descriptive research provides a complementary approach to questionnaire-based assessment methods that rely on summative judgments about the way people relate to themselves.

Our observations converged with self-report measures in some respects, while paradoxically diverging in ways that may call into question the meaning of some questionnaire-based self-compassion scores. We identified several themes that fit conceptually within a broad theoretical construct of self-directed compassion, such as self-encouragement and acceptance of personal limitations. These themes tended to group together in factor analysis and to relate to self-reported shame, self-criticism, and self-compassion in the expected directions, adding credence to their presumed compassionate function. However, the relative infrequency with which we observed compassionate responses was itself a surprising and central finding: about 14 and 7 % of responses to failure and rejection scenarios, respectively. Furthermore, even these responses varied in the degree of compassion that might be inferred: for example, the motivation for phrases such as “Practice makes perfect” could range from gentle acceptance of one’s imperfections to a less compassionate, generic self-direction. Some expected types of self-compassionate thoughts were virtually absent: for example, thoughts that appeared to reference the common human condition comprised less than 1 % of codable responses, leading us to wonder whether the concept of common humanity was understood or acknowledged within this population (Table 7).

Although this paucity may be surprising, it fits with the general observation that within conventional society the concept of the “inner critic” is salient and readily understood, yet we do not recognize the parallel concept of an “inner friend” or “inner support person.” Questionnaires may provide an equal number of items assessing both self-compassionate and uncompassionate tendencies, but if some respondents have less experiential understanding of self-compassion, it could limit their ability to assess accurately their own levels of self-directed compassion (see also Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015). If this were true, then in addition to traditional self-report questionnaires, assessment of self-reported compassion could be enhanced by assessing the depth of one’s experiential understanding of what a “5” on a 5-point Likert scale item assessing self-directed compassion might look like.

It is possible that other response categories, particularly social reasoning and problem-solving, served a compassionate role to some degree as they tended to co-occur alongside self-directed compassionate thoughts. In response to social rejection vignettes, reasoning generally involved imagining the social other’s perspective, thus demonstrating a motivation to understand others that is foundational to other-directed compassion. In general, a pragmatic, solution-oriented focus may be experienced as comforting or encouraging, thus serving an implicit self-care function. Consistent with Gilbert’s (2009) conceptualization of self-directed compassion, it may reflect taking action to mitigate one’s own suffering. Associations have been reported between self-compassion and action-oriented coping (e.g., Neff, Rude, & Kirkpatrick, 2007).

‘Acknowledging experience’ was a heterogeneous category that awaits further study. It gives us pause, that in response to failure vignettes, acknowledgment of experience loaded inversely on the factor that included problem-solving, self-encouragement, and self-care. For social rejection vignettes, acknowledging experience loaded onto a factor that included avoiding experience and not seeking further information. Perhaps in some cases these responses may have served to minimize or invalidate experienced vulnerability or discomfort, an approach antithetical to self-directed compassion.

What Did a Lack of Self-Compassion Sound like?

Potentially uncompassionate responses were more frequent and varied. Although originally grouped according to Neff’s theorized domains of self-judgment, isolation and over-identification, factor analysis suggested alternate groupings for the response categories based on their co-occurrence. Across both scenario types, two factors were identified that characterized strong, uncompassionate responses to self and others, respectively. Loading highly on the Strong Negative factors were extreme response categories that the coding team considered to be acutely uncompassionate: critical self-judgment and the two forms of isolation that reify a narrative that one is alienated from, and victimized by, others. Catastrophizing responses were by definition extreme, and would particularly undermine self-regulation. Taken together, these categories accounted for six and 19% of responses to failure and social rejection scenarios, respectively. The Strong Negative factors were most strongly associated with self-report measures of shame, self-criticism, low self-esteem, and low self-compassion.

Externalizing factors generally indicated a clear lack of compassion toward others in both failure and rejection contexts. They were negligibly associated with shame, self-criticism, self-esteem and self-compassion, but were uniquely, inversely associated with guilt; this is consistent with research relating externalization to a lack of guilt (Muris et al., 2016; van Tijen, Stegge, Terwogt, & van Panhuis, 2004). Indeed, a central function of externalization is to deflect and minimize personal accountability, and its accompanying disavowal of personal vulnerability is a barrier to self-directed, as well as other-directed, compassion.

Other factors were more situation-specific. Of particular note, Situational Shame in response to failure involved avoidance, fear of others’ reaction, and perceived isolation. For example, responses to receiving a failing grade on a test may include: worrying how their parents would react, wanting to hide it from them, and believing they had let them down. Such responses characterize the experience of shame in response to a specific event, which has been distinguished from more trait-like shame-proneness involving global negative self-judgments (Goss & Allan, 1994; Tangney, 1996) such as those included in the Strong Negative factor. Situational Shame and Strong Negative factor scores were negligibly associated, suggesting minimal conceptual or functional similarity. Furthermore, Situational Shame was only modestly related to self-report measures of shame, self-criticism, low self-esteem, and low self-compassion. Considering the expressed fear of others’ reactions, we speculate that responses conveying elements of situational shame might be influenced by perceived pressure from others regarding the individual’s performance, at either a societal or relationship-specific level.

Other factors were less easily evaluated as generally compassionate or uncompassionate. Non-acceptance of failure is considered uncompassionate from a philosophical and theoretical perspective, in that compassion is said to entail acceptance of experiences (Neff, 2003a). However, from a functional perspective, it could be argued that some degree of situational non-acceptance of failure (e.g., wishing the outcome were different; seeking information about what went wrong and how to do better) would be pragmatic, depending on one’s goals. Future research could investigate whether such non-acceptance is associated with conscientiousness, competitiveness, agency, and/or achievement. In a similar vein, acceptance of social rejection and its potential negative implications might be seen as compassionate due to the theoretical connection between acceptance and self-compassion, but it is also possible that these responses might influenced by low perceived social agency. Ambiguities such as these suggest that the degree to which some of these thoughts might be uncompassionate may depend on their frequency and severity. They also argue for the importance of considering responses in their broader context when appraising whether they serve a compassionate or uncompassionate function. For instance, although rigid avoidance of distressing emotions typically is seen as problematic, temporary avoidance in order to get through a discrete difficult experience has been considered adaptive (Herman-Stabl, Stemmler, & Petersen, 1995; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and could be a compassionate response, depending on one’s immediate needs and internal resources. Similarly, exerting a certain degree of pressure to achieve might be consistent with one’s goals, and depending on the broader context, might differentiate self-directed compassion from passive self-indulgence.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Taken together, a variety of commonly experienced failure and rejection scenarios generated a wide array of codable responses. Use of a diverse development sample, and a large application sample, allowed us to achieve good interrater reliability on most frequently observed categories and increased confidence in the generalizability of our findings to similar university samples. Although some categories occurred infrequently, future research may find that these categories are more relevant to other populations. For instance, narcissism (self-protective isolation) was an extremely rare category in our sample but might be more frequently observed in clinical or forensic populations. Moreover, infrequently observed forms of self-directed compassion could indicate specific targets for intervention.

Use of self-directed compassion as a theoretical perspective to interpret responses necessarily restricted our findings; other researchers may choose to identify and group response categories differently depending on their theoretical lens. We also were limited by the brevity of individual responses. Although we were able to make our best guess regarding a number of salient functional distinctions, we cannot be certain of these functions (Russell, 1982). Categories are based on the coding team’s best guess about statement function, following careful group discussion of difficult-to-code statements, and erring on the side of caution by considering responses uncodeable when conflicting interpretations were possible. Future research addressing the function of these responses could validate or elucidate the functional distinctions we inferred.

Of theoretical interest was the differentiation of self-directed compassion and self-esteem within the “liking self” category. Despite the intriguing conceptual distinctions between these constructs (Neff, 2003b), they share a great deal of overlap since both are a form of positive self-regard. Clear references to achievement-based self-judgment and social comparison were excluded from the category, due to their theoretical association with self-esteem; however, we cannot be certain that some responses coded as compassionately “liking self” could also have implicitly involved these processes.

Particularly ambiguous were responses categorized as acknowledging experience, one of the most common types of automatic thoughts. Thoughts assigned to this category typically involved labeling one’s emotion (e.g., “I feel angry,”) or simply restating the situation (e.g., “They don’t want to go out with me.”) The first step in a mindful response is to acknowledge moments of suffering in just this way. To the extent that feelings and situations were acknowledged with acceptance and openness, such acknowledgment would exemplify mindfulness. However, if such statements reflected resistance, or were a precursor to over-identification, then they would not be considered mindful. The statements themselves did not provide enough information to discriminate between these possibilities. Thus, we did not include this frequently used category within the mindful awareness construct, and expect that it is quite heterogeneous: it awaits future research.

A key limitation of the current study is that immediate thoughts were self-reported. Internal self-talk is difficult, if not impossible, to “observe” without reliance on self-report, which likely functions as a filter. Although asking for spontaneous thoughts to discrete scenarios arguably provided more immediate, genuine responses than the summative judgments collected on questionnaires, participants may not report their first three automatic thoughts for a variety of reasons (e.g., low insight, avoidance, social desirability). Requiring participants to type, rather than verbally report, their responses may have additionally obscured their immediate thoughts, although in the current era emerging adults arguably may find it easier to communicate openly via text than interpersonally (Hall, Feister, & Tikkanen, 2018). Nonetheless, future research should consider collecting spoken responses from participants, such as in the form of a structured interview, to explore whether the nature of spoken participant responses differs from the typed responses collected in the present study. Furthermore, although a strength of the current study, a focus on immediate thoughts also is a limitation since, at a deeper level, self-directed compassion extends beyond verbal language. It is unlikely that a heartfelt openness toward oneself can be fully captured through verbal communication. Considered one of the “Four Immeasurables” in Buddhist philosophy (Nhat Hahn, 1991), deeply authentic compassion may ultimately defy our attempts to measure it. Observation of mindful awareness was particularly hindered by a reliance on words: the act of simply being present is often not accompanied by words.

Despite unavoidable limitations and complexities, observing self-directed compassion as a relational process unfolding in real time provides a necessary foundation to the field. Future research is required to clarify and extend these findings in populations that differ by age, culture, and sub-culture. Since the meaning of participants’ responses is presumably highly culturally dependent, such research will require qualitative analysis to ascertain the breadth of responses and their meaning, with groups of coders who share the cultural perspective. Vignettes also may require modification to increase their relevance to the population under study. Understanding the observable forms it might take across these different cultural perspectives may ultimately enrich our understanding of self-directed compassion and how to foster its development.

Notes

Please contact the first author for information regarding how to access the complete coding manual.

The narcissism category was the only category identified in the application but not the development sample.

Please contact the first author for correlations with the positive and negative halves of the SCS.

For zero-order correlations, the absolute value is the effect size (Cohen, 1992).

References

American College Health Association. (2017). American College Health Association-national college health assessment II: Undergraduate student reference group data report fall (p. 2016). Hanover, MD: American College Health Association.

Arslan, C. (2016). Interpersonal problem solving, self-compassion and personality traits in university students. Educational Research and Reviews, 11(7), 474-481. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2015.2605.

Barnard, L. K., & Curry, J. F. (2011). Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of general psychology, 15(4), 289. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025754.

Berry, K., Kowalski, K., Ferguson, L., & Mchugh, T. (2010). An empirical phenomenology of young adult women exercisers’ body self-compassion. Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, 2(3), 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/19398441.2010.517035.

Blackie, R. A., & Kocovski, N. L. (2019). Trait self-compassion as a buffer against post-event processing following feedback. Mindfulness, 10, 923–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1052-7.

Braun, C., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London, UK: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353515614115.

Breines, J. G., McInnis, C. M., Kuras, Y. I., Thoma, M. V., Gianferante, D., Hanlin, L., et al. (2015). Self-compassionate young adults show lower salivary alpha- amylase responses to repeated psychosocial stress. Self and Identity, 14(4), 390–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2015.1005659.

Buddhaghosa, B. (1975). The path of purification (Nanamoli, B., Trans.). Sri Lanka, Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society https://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/nanamoli/PathofPurification2011.pdf.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393980.

Campion, M., & Glover, L. (2017). A qualitative exploration of responses to self-compassion in a non-clinical sample. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 1100–1108. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12408.

Castilho, P., Pinto, G. J., & Duarte, J. (2015). Evaluating the multifactor structure of the long and short versions of the SCS in a clinical sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(9), 856–870. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22187.

Cicchetti, V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

Core Team, R. (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing http://www.R-project.org/.

Costa, J., Marôco, J., Pinto-Gouvei, J., Ferreira, C., & Castilho, P. (2016). Validation of the psychometric properties of the self-compassion scale. testing the factorial validity and factorial invariance of the measure among borderline personality disorder, anxiety disorder, eating disorder and general populations. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 23(5), 460–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1974.

Cumming, G. (2014). The new statistics: Why and how. Psychological science, 25(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613504966.

Davidson, R. J., & Kaszniak, A. W. (2015). Conceptual and methodological issues in research on mindfulness and meditation. American Psychologist, 70(7), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039512.

Fabrigar, L. R., & Wegener, D. T. (2012). Understanding statistics. Exploratory factor analysis. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199734177.001.0001.

Falconer, C. J., King, J. A., & Brewin, C. R. (2015). Demonstrating mood repair with a situation- based measure of self-compassion and self-criticism. Psychology and Psychotherapy:Theory, Research and Practice, 88(4), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12056.

Fisher, M. L., & Exline, J. J. (2010). Moving toward self-forgiveness: removing barriers related to shame, guilt, and regret. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(8), 548–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00276.x.

Germer, C. K. (2009). The mindful path to self-compassion: Freeing yourself from destructive thoughts and emotions. New York, N.Y., U.S.A: The Guilford Press https://www.guilford.com/books/The-Mindful-Path-to-Self-Compassion/Christopher-Germer/9781593859756.

Germer, C. K., & Neff, K. D. (2013). Self-compassion in clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(8), 856–867. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22021.

Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind. London, United Kingdom: Constable.

Goodwin, L. D., & Leech, N. L. (2006). Understanding correlation: Factors that affect the size of r. The Journal of Experimental Education, 74(3), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.74.3.249-266.

Goss, K., & Allan, G. S. (1994). An exploration of shame measures – I: The other as shamer scale. Personality and Individual differences, 17(5), 713–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)90149-X.

Hall, E. D., Feister, M. K., & Tikkanen, S. (2018). A mixed-method analysis of the role of online communication attitudes in the relationship between self-monitoring and emerging adult text intensity. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.002.

Herman-Stabl, M. A., Stemmler, M., & Petersen, A. C. (1995). Approach and avoidant coping: Implications for adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24(6), 649–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01536949.

Iskender, M. (2009). The relationship between self-compassion, self-efficacy, and control beliefs about learning in Turkish university students. Social Behavior and Personality, 37, 711–720. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2009.37.5.711.

Kaiser, H. F. (1958). The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 23, 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289233.

Köhle, N., Drossaert, C. H. C., Jaran, J., Schreurs, K., Verdonck-de Leeuw, I. M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017). User-experiences with a web-based self-help intervention for partners of cancer patients based on acceptance and commitment therapy and self-compassion: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 17(225), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4121-2.

L’Estrange, K., Timulak, L., Kinsella, L., & D’Alton, P. (2016). Experiences of Changes in Self- Compassion Following Mindfulness-Based Intervention with a Cancer Population. Mindfulness, 7(3), 734–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0513-0.

Lazarus, R, S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_215

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Allen, A. B., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-related events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 887–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887.

López, A., Sanderman, R., Smink, A., Zhang, Y., van Sonderen, E., Ranchor, A., & Schroevers, M. J. (2015). A reconsideration of the self-compassion scale’s total score: Self-compassion versus self-criticism. PLOS ONE, 10(7), e0132940. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132940.

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., Heijmans, J., van Hulten, S., Kaanen, L., Oerlemans, B., et al. (2016). Lack of guilt, guilt, and shame: A multi-informant study on the relations between self-conscious emotions and psychopathology in clinically referred children and adolescents. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 25(4), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0749-6.

Muris, P., Otgaar, H., & Pfattheicher, S. (2019). Stripping the forest from the rotten trees: Compassionate self-responding is a way of coping, but reduced uncompassionate self-responding mainly reflects psychopathology. Mindfulness, 10, 196–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1030-0.

Neely, M. E., Shallert, D. L., Mohammed, S. S., Roberts, R. M., & Chen, Y. (2009). Self-kindness when facing stress: The role of self-compassion, goal regulation, and support in college students’ well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 33, 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9119-8.

Neff, K. D. (2003a). Development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390209035.

Neff, K. D. (2003b). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390129863.

Neff, K. D. (2012). The science of self-compassion. In C. Germer & R. Siegel (Eds.), Compassion and Wisdom in Psychotherapy (pp. 79–92). New York: Guilford Press.

Neff, K, D. (2015). Scales for researchers. http://self-compassion.org/self- compassion-scales-for-researchers/.

Neff, K. D., & Dahm, K. A. (2014). Self-compassion: What it is, what it does, and how it relates to mindfulness (pp. 121–140). In M. Robinson, B. Meier, & B. Ostafin (Eds.), Mindfulness and Self-Regulation. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2263-5_10.

Neff, K. D., & McGehee, P. (2010). Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and Identity, 9(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860902979307.

Neff, K. D., & Vonk, R. (2009). Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of related to oneself. Journal of Personality, 77, 23–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00537.

Neff, K. D., Rude, S. S., & Kirkpatrick, K. (2007). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 908–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.08.002.

Neff, K. D., Tóth-Király, I., Yarnell, L. M., Arimitsu, K., Castilho, P., Ghorbani, N., et al. (2019). Examining the factor structure of the self-compassion scale in 20 diverse samples: Support for use of a total score and six sub scale scores. Psychological Assessment, 31(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000629.

Nhat Hahn, T. (1991). Old path white clouds: Walking in the footsteps of the Buddha. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/2059104.

Pfattheicher, S., Geiger, M., Hartung, J., Weiss, S., & Schindler, S. (2017). Old wine in new bottles? The case of self-compassion and neuroticism. European Journal of Personality, 31(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2097.

Redden, E, K. (2019) Development and application of a vignette measure of self-compassion (Doctoral Dissertation). https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/xmlui/handle/10214/15069.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Russell, D. (1982). The Causal Dimension Scale: A measure of how individuals perceive causes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(6), 1137–1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.6.1137.

Sharma, M., & Davidson, C. (2015). Self-compassion in relation to personal initiativeness, curiosity and exploration among young adults. Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 6(2), 185–187.

Shoukri, M., Asyali, M., & Donner, A. (2004). Sample size requirements for the design of reliability study: Review and new results. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 13(4), 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1191/0962280204sm365ra.

Sirois, F. M. (2015). A self-regulation resource model of self-compassion and health behaviour intentions in emerging adults. Preventive Medicine Reports, 2, 218–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.03.006.

Sutherland, O., Dawczyk, A., De Leon, K., Cripps, J., & Lewis, S. (2014a). Self-compassion in online accounts of nonsuicidal self-injury: An interpretive phenomenological analysis. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 27(4), 409–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/9515070.2014.948809.

Sutherland, L., Kowalski, K., Ferguson, L., Sabiston, C., Sedgwick, W., & Crocker, P. (2014b). Narratives of young women athletes’ experiences of emotional pain and self- compassion. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 6(4), 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2014.888587.

Tangney, J. P. (1996). Conceptual and methodological issues in the assessment of shame and guilt. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(9), 741–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(96)00034-4.

Tangney, J. P., Wagner, P. E., Gavlas, J., & Gramzow, R. (1991). The Test of Self-Conscious Affect for Adolescents (TOSCA-A). Fairfax, VA: George Mason University. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_954-1.

Terry, M. L., Leary, M. R., & Mehta, S. (2013). Self-compassion as a buffer against homesickness, depression, and dissatisfaction in the transition to college, self and identity. Self and Identity, 12(3), 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2012.667913.

Thompson, R., & Zuroff, D. C. (2004). The Levels of Self-Criticism Scale: Comparative self-criticism and internalized self-criticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(2), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00106-5.

van Tijen, N., Stegge, H., Terwogt, M. M., & van Panhuis, N. (2004). Anger, shame and guilt in children with externalizing problems: An imbalance of affects? European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 1(3), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620444000175.

Williams, M. J., Dalgleish, T., Karl, A., & Kuyken, W. (2014). Examining the factor structures of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire and the SCS. Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035566.

Woekel, E., & Ebbeck, V. (2013). Transitional bodies: A qualitative investigation of postpartum body self-compassion. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 5(2), 245–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2013.766813.

Yamaguchi, A., Kim, M. S., & Akutsu, S. (2014). The effects of self-construals, self- criticism, and self-compassion on depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.013.

Acknowledgements

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The General Research Ethics Board at the University of Guelph approved this study. We certify that this study is compliant with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later addenda. Informed consent was obtained from each participant in this study.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Redden, E.K., Bailey, H., Katan, A. et al. Evidence for self-compassionate talk: What do people actually say?. Curr Psychol 42, 748–764 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01339-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01339-2