Abstract

High comorbidity of anxiety and depression poses challenges to research and treatment in clinical settings. The current study was set out to investigate whether respondents can be separated into discrete depressive and anxious subgroups or reveal a continuous distribution throughout the population based on the symptoms of depression and anxiety. In addition, we also explored the role of rumination, automatic thoughts, dysfunctional attitudes, and thought suppression as transdiagnostic factors. Psychometric instruments including Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ), Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale-Revised (DAS-R), Ruminative Response Scale – Short Form (RRS-SF), and White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI) were completed by 310 undergraduates. Item responses to the BDI and BAI were subjected to latent class analysis (LCA). The LCA showed that three homogenous subgroups exist: normal, subclinical, and psychopathology latent classes. Findings supported the dimensional model rather than the categorical distinction between anxiety and depression. Strong covariances between anxious and depressive symptoms across latent subgroups were observed. Having controlled for age and gender, automatic thoughts, dysfunctional thinking, rumination, and thought suppression were all found significant transdiagnostic factors. Anxiety and depression, as frequently co-occurring clinical conditions, can be best understood in a continuum rather than taxonomic classifications. Individuals more prone to use maladaptive cognitive emotional regulation strategies seem to be at greater risk of psychopathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The co-occurrence of one clinical entity with another beyond chance is a necessity for being regarded as a close etiological relationship within them. The experience of fear and anxiety is commonplace across a wide range of psychiatric disorders (Goodwin 2015). In such a sense, various genres of anxiety disorders as a matter, of course, are highly comorbid with each other that 74.1% of those individuals with agoraphobia, 68.7% of those with a phobia, and 59.9% of those with social phobia also met criteria for another anxiety disorder in US general population (W. J. Magee et al. 1996). More recently, community based estimates of the lifetime caseness risk/12-month prevalence included major depressive disorder: 29.9 / 8.6%; specific phobia: 18.4 / 12.1%; social phobia: 13.0/7.4%; generalized anxiety disorder: 9.0/2.0%; separation anxiety disorder: 8.7/1.2%; panic disorder: 6.8%/2.4%; and agoraphobia: 3.7/1.7% (Kessler et al. 2012). In the US National Comorbid Survey, Kessler et al. (1996) showed that 58.0% of those with lifetime DSM-III-R diagnoses of major depression also met criteria for a comorbid anxiety disorder and the comorbidity rate between major depression and anxiety disorders was %51.2 for 12-month diagnosis, with widely different rates across disorders. Co-occurrence of depressive disorders and anxiety disorders is typically identified in community populations recruited from various countries (Hofmeijer-Sevink et al. 2012; Mathew et al. 2011).

Tripartite Model of Depression and Anxiety

Much of the evidence emerges with the overlaps between depressive and anxious symptomatology based on the community-based estimates of categorical groups of afflicted individuals as defined in nosological classifications (Jenkins et al. 2020; Price et al. 2019; Routledge et al. 2017; Taporoski et al. 2015). One of the most prevailing notions in regard to the affect regulation is the two-dimensional approach in which the Negative Affect (NA) constitutes one pole generally related to subjective distress, and the Positive Affect (PA) constitutes the other referring to happiness, with stronger linkages to sad mood relative to fear (Watson and Tellegen 1985; Watson et al. 1999). The tripartite model of affect asserted that depressive symptomatology is featured by anhedonia and anxiety is characterized by somatic tension and hyperarousal, while the subjective distress appears to be the shared general dimension of affect dysregulation in both depression and anxiety (L. A. Clark and Watson 1991). Compelling evidence supporting the assumptions of the tripartite model has emerged in an array of factor analytic investigations of anxiety and depression symptoms in large clinical groups that a general distress factor or negative affect and two first-order factors representing the discrete symptom constellations of anxiety and depression were consistently observed; with most of the variance was explained by the general stress factor across these studies (D. A. Clark et al. 1994; Steer et al. 1995, 1999). In a similar vein, a confirmatory meta-analysis of the latent structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond and Snaith (1983) found a bifactor structure, involving a general distress factor and two orthogonal dimensions of anxiety and depression; however, most notably, 73% of the total variance was accounted for by the general distress factor (Norton et al. 2013).

More recent investigations of tripartite model anxiety and depression addressed overlapping and discrepancy factors in explaining the co-occurring features of these two clinical entities. In an experimental memory task study testing the assumptions of the tripartite model, Bowman et al. (2019) identified that poor prospective memory performance is the hallmark of anxious arousal and negative affect, but not depressive symptoms or positive affect. A longitudinal study among college students reported a significant interaction effect between general distress and neuroticism evoked by daily hassles contributed prospective elevations in general distress and specific anxiety symptoms but not in specific depressive symptoms (He et al. 2018). A three-wave study of chronotype in relation to tripartite model over 30 months found that higher levels of depressive symptomatology, lowered positive affect, and decreased anxiety was predicted by eveningness, which was prospectively associated with elevated depressive symptomatology but not anxious arousal (Haraden et al. 2019). A weekly follow up study of women over five weeks revealed strong associations of both rumination and worry as transdiagnostic factors with general distress, which was characterized by shared symptoms of anxiety and depression but not with anxious arousal or anhedonia (Kalmbach et al. 2016).

Beck’s Cognitive Behavioral Model of Anxiety and Depression

From the lenses of the cognitive-behavioral theory of emotional disorders, individuals more apt to develop and maintain psychological distress seem to view the world, their self, and the future from a mental filter that delineates negative aspects of their experiences while minimizing the positive facades of the life events. The model holds the view that this negative cognitive information processing originates from specific structures of learned thinking patterns, so-called ‘schemas’ (A. T. Beck et al. 1979; J. S. Beck 2011; Ozdel et al. 2014). The term ‘mode’ presents a fabulous synthesis of the conceptualization of the ‘schemas’ with the structural elements of personality. The mode, in general, infers a constellation of interrelated schemas organized to the fulfillment of one’s demands on survival and adaptation (A. T. Beck 1996). Also, the cognitive model of psychopathology readily acknowledges that information processing of one’s personal experiences involves automatic (effortless, involuntary, and unintentional) and reflective (effortful, voluntary, and attentional) processing implicated in emotional regulation (A. T. Beck and Clark 1997). Accordingly, excessively low threshold for activation of the primal threat mode or self-protective mode which is responsible for inflated appraisals of potential danger, the threat of harm to vital resources is thought to be largely automatic due to the need for assurance of rapid and efficient response for the survival in anxiety disorders (A. T. Beck and Haigh 2014; D. A. Clark and Beck 2011b; McNally 1995). On the other hand, major depressive symptomatology is suggested to be largely typified by more conscious and intentional but less uncontrollable information processing of negatively valanced thought content relative to anxiety disorders (Teachman et al. 2012). The cognitive-behavioral model holds the view that, unlike anxiety which refers to an excessive reaction disproportionate originated from threat overestimation (D. A. Clark and Beck 2011a), severe depression is understood as a strong reaction to perceived loss of an investment in a vital resource that leads maladaptive overreaction of self-expansive mode is associated with an interaction between bio-psycho-social vulnerability factors and depressogenic attribution styles (A. T. Beck and Bredemeier 2016; A. T. Beck and Haigh 2014). In clinical groups, differential associations of automatic thoughts as measured by the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ; Hollon and Kendall 1980) and dysfunctional thoughts as indexed by the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS; Weissman and Beck 1978) with psychopathology was demonstrated by Hill et al. (1989) that the ATQ scores were more likely to be specific to depressive symptomology; whereas, the DAS revealed a nonspecificity concerning depression. A more recent survey among 2158 Chinese adolescents showed that social- and physical-threat related automatic thoughts were predictive of anxious arousal, and dysfunctional thoughts about personal failure were associated with depressive symptomatology (Yu et al. 2017). A meta-analytic structural equation modeling analysis of six affect-specific cognitive vulnerability facades of depression (pessimistic inferential style, dysfunctional attitudes, and rumination) and anxiety (anxiety sensitivity, intolerance of uncertainty, and fear of negative evaluation) identified moderate to strong correlations and a one-factor model best fit to the data on 159 effect sizes from 73 studies, suggesting a shared etiological underpinning in terms of maladaptive information processing between these two clinical entities (Hong and Cheung 2014).

Transdiagnostic Factors in Depression and Anxiety

The high degree of co-occurrence across mental disorders, particularly anxiety and depression (Boysan 2019; T. A. Brown et al. 2001) has spanned the research on underlying mechanisms of comorbidity, generally used as transdiagnostic factors (Harvey et al. 2004). Cognitive vulnerabilities such as repetitive unconstructive thinking have long been recognized as transdiagnostic factors (Ehring and Watkins 2008; Mansell et al. 2008; Watkins 2008). One of the specific types of unconstructive repetitive thinking most frequently investigated in mood and anxiety disorders is rumination. Even though various models of rumination have been conceptualized (Koster et al. 2011; Krys et al. 2020; Miller et al. 2020; Ricarte et al. 2018; Watkins and Roberts 2020), as the most influential notion, response styles theory defines rumination as patterns of passively and pervasively thinking about one’s emotional symptoms as well as the causes and consequences of these symptoms (Lyubomirsky et al. 2015). A tendency to ruminate about one’s problems and emotions is relatively stable over time and contributes to perseveration of negative affective states (Silveira et al. 2020; Whisman et al. 2020), particularly self-focused rumination (Bagby et al. 2004). Rumination may lead to negative emotional states through different mechanisms that ruminative thinking is a significant correlate of more dysfunctional information processing (Kaiser et al. 2019; Kaiser et al. 2018), over-focusing on negative aspects of a stressful situation (Yasinski et al. 2016), less effective problem solving (Jones et al. 2017), failure in getting social support (Hasegawa et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2019), and difficulties in taking in action for active coping with problems (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1994). From the early times, research on the potential influence of rumination on emotion regulation and assumptions of response style theory has heavily relied on causal mechanisms of depression that various lines of studies have provided strong evidence for the significant associations between rumination and depression (DeJong et al. 2016; Watkins 2018; Zhou et al. 2020). In keeping with the prevailing notion, Cox et al. (2001) qualified ruminative response style as ‘depressogenic’ and a potential predictor of specific features of depressive symptoms. Nevertheless, despite the well-established association between rumination and depression, a growing body of evidence identified significant linkage between anxiety and depression. Experimental studies have showed that induction of rumination in the context of stressful situations may fuel both anxious and depressive symptoms (Blagden and Craske 1996; McLaughlin et al. 2007). Further studies highlighted the significant contribution of ruminative thinking style to anxiety that rumination was significantly associated with concurrent anxiety symptoms (Muris et al. 2004; Talavera et al. 2018) and prospectively associated with anxious emotional states (Calmes and Roberts 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema 2000). More importantly, the ruminative response style was outlined as a full mediator of the concurrent associations between anxiety and depression in youths and partial mediators of these clinical entities in adults. In addition, prospective relationships between depressive and anxious symptomatology were fully mediated by rumination as well (McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema 2011). Meta-analytic explorations of relationships between rumination, depression, and anxiety showed moderate associations of ruminative response with anxiety and depression, and the relations were mutually inclusive that anxiety and depression exert a significant independent effect on rumination (Kirkegaard Thomsen 2006; Olatunji et al. 2013).

The ironic process theory of mental control posits that, particularly under conditions of high mental load, thought suppression failed to suppress unwanted thoughts instead may yield intrusions escalate to a much higher level of frequency (Wegner 1994). The theory put forth two cognitive information processes that, in a bid to divert attention from unwanted mental content as a function of the effortful and conscious cognitive process may maintain vigilance for occurrences of unwanted thought in awareness and trigger for taking further action of the ordering process at an effortless and unconscious level. Research has shown that suppressed thought is characterized by the increased return of the suppressed content while precluding other related conscious information processing and the difficulty keeping suppressed material out of mind (Wegner et al. 1987). The resurgence of unwanted thoughts during suppression infers the ‘immediate enhancement effect’ and the prolonged enhancement of intrusions after the suppression of the ‘rebound effect’ (Wenzlaff and Wegner 2000). The first meta-analytic analysis of largely non-clinical samples found that, unlike the theoretical assumptions of paradoxical effects of thought suppression, people generally entirely suppress thoughts with the lack of initial enhancement effect. However, a small to a medium rebound effect of intrusive, unwanted thoughts after cessation of suppression were identified across studies were identified (Abramowitz et al. 2001). As with the rumination research, early studies of paradoxical effects of mental control have primarily focused on dysphoric states that numerous studies have identified robust connections between chronic thought suppression and depression (Najmi and Wegner 2008; Wenzlaff 2005). A variety of cognitive mechanisms have been identified to conceive the central role of the mental control process in emotional dysregulation, particularly depressive internal states. First, consistent with the basic tenets of a paradoxical process theory of mental control, an incentive for avoidance from the depressogenic thought content often result in a boomerang effect that magnifies the endorsement of negative cognitions (Wenzlaff et al. 1988). Second, at-risk individuals more apt to engage in though suppression may probably mask their vulnerability to maladaptive negative thinking. Under the conditions of cognitive load, however, those of individuals high in a tendency to mask negative inferences through mental control strategies are seemed to be more susceptible to retrieve negative thought content more frequently than those of individuals low in thought suppression (Wenzlaff and Bates 1998). Third, automatic processes need few attentional resources and remain almost intact in depression (Hartlage et al. 1993); whereas conscious, effortful processes are depleted in an extent to which depression-prone individuals routinely engage in maladaptive cognitive strategies such as mental control in order to suppress negative thinking patterns (Najmi and Wegner 2009). Fourth, mental control processes involve in diverting attention to other cognitive sources or distracters to target negative thought content for suppression. In cases with depression, it was observed that distracters were mood-congruent, reflecting the characteristics of negative thoughts to be suppressed that are readily most accessible (Renaud and McConnell 2002; Wenzlaff et al. 1991). Despite the thorough descriptions for the underpinnings of mental control processes in depression, potential mechanisms in relation to suppression in anxious arousal have still remained elusive as yet. Generally speaking, people with anxiety problems, attempting to suppress thoughts frequently appear to benefit from suppression (J. C. Magee and Zinbarg 2007). However, systematic reviews have concluded that studies exploring clinical samples with depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder do not appear to indicate the higher occurrence of suppressed unwanted thoughts than non-clinical samples (Najmi and Wegner 2008; Purdon 1999), at least the evidence for the significant differences in favor of clinical groups was weak (Rassin et al. 2000). An extensive meta-analysis of paradoxical influence of mental control across psychopathology groups showed that, although immediate enhancement effect in concert with personal efforts of thought suppression seems to be equivalent in clinical and non-clinical samples, the rebound effect revealed an equivalent or decreased effect for generalized anxiety disorder (J. C. Magee et al. 2012).

Present Study

Over the decades, it has been well-established that maladaptive thinking patterns such as dysfunctional attitudes, including unrealistic expectations and automatic thoughts, including cognitive biases, are implicated in psychopathology as cognitive vulnerability factors (A. T. Beck and Haigh 2014). Rumination is unconstructive repetitive thinking and thought suppression as a mental control process mediates the reciprocal relationships between core maladaptive thinking patterns and external stimuli that inform a vicious cycle of the formation and perseveration of the emotional disorders, particularly depression and anxiety (Wells and Matthews 1996). The current study aimed to explore the heterogeneity of anxiety and depression symptoms as well as the differences in symptom patterns of latent subgroups in a sample of community population using the latent class analysis (LCA). To date, few studies addressed LCA of anxiety and depression symptoms. In an early investigation on the data from the Epidemiological Catchment Area Program, Eaton et al. (1989) extracted three latent classes for anxiety symptoms only, depression symptoms and 41 anxiety and depression symptoms using various LCAs. Items tapped into the Anxious / Depressed subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist completed by parents or caregivers of 1987 children and adolescents were subjected to LCA. Scholars reported a three-latent-class model best fit to the data, including no problems, mild problems, and moderate anxiety/depression problems (Wadsworth et al. 2001). In a sample of 616 psychiatric outpatients, Podlogar et al. (2018) explored the overlapping and distinctive features of anxiety and depression symptoms with suicidal thoughts. In line with previous studies, LCA identified a three-latent-class model. Anxiety and depression symptoms, along with suicidality, indicated a distribution on a continuum rather than differentiation according to symptom subtypes. The 3-class solution was a higher suicide-risk class with high in depression and anxious arousal, followed by a lower suicide-risk class with moderate levels of depression and anxious arousal, and a non-suicidal class with low levels of depression and anxiety. In line with the previous literature, we speculated that we would identify three latent-class model best fit to the present data.

The analytic data procedures followed the need to explore the symptom patterns of optimal latent classes of depression and anxiety symptoms. Having selected most optimally separating classes based on response patterns of the anxious and depressive symptomatology, we investigated individual symptom differences across subgroups through carrying out a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). We speculated that most of the symptoms of anxiety and depression would reveal mostly shared variance with the overall constellation of negative affectivity; thereby differing significantly across latent classes, with each represents a specific level in emotional regulation or dysregulation. Taken together, to explore the relationships of the latent-classes representing the information processing capacity for negative affectivity in terms of depressive and anxious symptomatology with cognitive vulnerability factors of automatic thoughts, dysfunctional thinking, ruminative responses, and thought suppression, a multinomial logistic model was analyzed. We also carried out a regression of transdiagnostic factors on post-Bayesian membership probabilities. It is hypothesized that cognitive vulnerability factors as transdiagnostic factors would be associated with escalations in affective symptom severity, as indicated by latent classes.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The initial sample consisted of 324 undergraduate volunteers; however, 14 participants were discarded from the analysis due to the incomplete psychometric instruments. The final sample was comprised of 310 college students, aged between 18 and 33 (M = 21.26, SD ± 2.00). 65.16% of the sample were female (n = 202). The participants were recruited from various majors of a university in Turkey through announcements in the classrooms. Volunteers were briefly informed about the procedures and purpose of the current study and then provided written informed consent. Respondents were not compensated for their participation. The local ethical committee approved the procedures and purposes of the study.

Instruments

A socio-demographic questionnaire prepared by the researchers, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), a revised version of the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS-R), Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ), Response Styles Scale – Short Form (RRS-SF), and White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI) were administered in the study.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The BDI is a 21-item self-report questionnaire with four response options for each item, ranging from 0 to 3. Items of the scale evaluate various symptoms of depression, including sadness, hopelessness, self-blame, feeling of guilt, fatigue, and loss of appetite. The BDI yields composite scores varying from 0 to 63 (A. T. Beck et al. 1979). The Turkish version of the BDI was indicated to have good reliability and validity properties, with a Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.80 (Hisli 1989).

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The BDI is a 21-item self-report questionnaire developed to evaluate somatic symptoms of anxiety (A. T. Beck et al. 1988). Respondents are asked to indicate how much they bothered by each symptom on a 4-point Likert type scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely). The Turkish version of the BAI had an internal consistency of α = 0.93 and good convergent validity with depression, and state and trait anxiety (Ulusoy et al. 1998).

Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ)

The ATQ is a 30-item self-report questionnaire developed to assess the frequency and severity of occurrence of negative thoughts and attributions. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (all the time). The instrument yields total scores ranging from 30 to 150 (Hollon and Kendall 1980). The Turkish version of the ATQ was translated by Sahin and Sahin (1992b). The Turkish version of the questionnaire revealed good reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.93 and validity with robust correlations with BDI (r = 0.75).

Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale-Revised (DAS-R)

The instrument consists of 40 self-report items anchored on a seven-point Likert type scale developed to assess dysfunctional thoughts and attitudes (Weissman and Beck 1978). The Turkish version of the DAS was translated by Sahin and Sahin (1992a). The 16-item revised version of the psychometric instrument was developed by Batmaz and Ozdel (2016). The internal consistency for the DAS-R was α = 0.84 for the overall scale.

Ruminative Response Scale – Short Form (RRS-SF)

The RRS-SF is a shortened 10-item self-administered scale developed to assess the ruminative response style in clinical and non-clinical populations. Items reminiscent of depressive symptoms were eliminated in the revision of the instrument. It was demonstrated by Treynor et al. (2003) that the short version had comparative psychometric properties with the original long-form (Nolenhoeksema and Morrow 1991). The Turkish version of the scale replicated the psychometric properties of the original English version with good reliability and validity. The internal reliability of the Turkish RRS-SF was α = 0.85 (Erdur-Baker and Bugay 2012).

White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI)

The WBSI is a 15-item self-report psychometric instrument developed to assess a tendency to suppress thoughts. Respondents are asked to rate on a 5-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).The WBSI yields a total score of 15–75 (Wegner and Zanakos 1994). The Turkish version of the instrument revealed good psychometric properties with a Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.90 and test re-test reliability of r = 0.80 (Altin and Gencoz 2009).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using Mplus 4.1 version (Muthén and Muthén 1998-2006) and Statistical Package for Social Statistics 23 version (IBM Corporation 2015). Initially, we computed The Pearson product-moments correlation coefficients between scale scores and descriptive statistics for psychometric measures.

The LCA is an advanced statistical method that allows for the identification of underlying latent homogenous latent classes of individuals in a sample. Using maximum likelihood with robust standard errors computed with the sandwich estimator (Yuan and Bentler 2000), we estimated conditional LCA models for item responses on the BDI and BAI that 42 depression and anxiety symptoms were subjected to categorical mixture analysis. The classification of participants via LCA is based on individual posterior membership probabilities. Model comparison in LCA is performed through the goodness of model fit statistics and model comparison statistics (Collins and Lanza 2013). In a simulation study (Nylund et al. 2007), the most reliable indicator of model fit in mixture analysis was identified as the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC; Schwarz 1978), for which the lowest values are indicative of better fit. Significance of model fit differences was quantified using the Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (LRT; Lo et al. 2001), which permits standard interpretation of the significance of the difference of the respective model with the nested latent class. We also used the Entropy index (Ramaswamy et al. 1993) as an indicator of internal consistency within an individual latent class. The closer the entropy index is to 1.00, the superior the classification quality is (Celeux and Soromenho 1996).

Next to the identification of optimal number latent classes, we carried out a one-way analysis of variance to explore symptom patterns for individual depressive and anxious symptoms of optimal latent classes. Also, using multiple analysis of covariance (MANCOVA), we estimated differences in scale scores across latent classes after controlling for age and gender. Using the Bonferroni multiple comparison tests, we made post hoc comparisons across groups. To explore the relationships between identified latent classed and psychological symptoms, we carried out multinomial logistic regression analysis in which the latent subgroups was treated as the dependent variable, and the ATQ, DAS-R, RRS, WBSI, and demographics (age and gender) were independent variables in the model. The group differences were evaluated using the likelihood ratio test.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

We computed the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients, means, standard deviations, and internal reliability for the scale scores. The correlation coefficients indicated strong associations of the BDI and BAI total with the ATQ total, whereas the association with the RSS, DAS-R, and WBSI were moderate. All correlation coefficients were statistically significant (p < 0.01). Correlations means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alphas are presented in Table 1.

LCA of the BDI and BAI Item Responses

To explore whether the current non-clinical sample of undergraduates could be well subsumed into homogenous subgroups using the symptoms of depression as measured by the BDI and anxiety as indicated by the BAI, we performed LCA. The LCA showed that the 3-latent-class model best fit the data on compiled depression and anxiety symptoms, with the lowest value of BIC and an insignificant difference from the 4-latent-class model. The model fit indices are presented in Table 2.

Comparisons of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms across Latent Classes

Next to the LCA, we began with comparing mean item scores of the BDI and BAI across three latent classes using a one-way analysis of variance. The Bonferroni multiple comparison tests was used to apply post hoc analysis across latent groups. We found that all 21 symptoms of depression, as measured by the BDI as well as anxiety symptoms as indexed by the BAI, significantly differed between latent classes, with large effect sizes of eta squared values greater than 0.14 (Cohen 1988). Two items of ‘item 18’. (η2 = 0.134) and ‘item 20’ (η2 = 0.026) in the BDI and two items of ‘item 16' (η2 = 0.118) and ‘item 19’ (η2 = 0.120) in the BAI revealed medium effect sizes in the ANOVAs. We were considering post hoc differences across latent groups, except for five items in the BDI (item 8, item 13, item 17, item 19, and item 20) and two items in the BAI (item 16 and item 19), respondents classified into the latent class 3 reported highest scores on all items of the BDI and BAI than other groups, followed by volunteers allocated into latent class 2 and latent class 1, respectively. Therefore, latent class 3 was labeled as ‘Psychopathology Group’; latent class 2 was labeled as ‘Subclinical Group,’ and latent class 1 was labeled as ‘Normal Group.’ Considering these exceptional items of the BDI (five items) and BAI (two items), we found that subjects in the psychopathology group had higher mean item scores than other subgroups; whereas, non-clinical and subclinical groups did not significantly differ on the mean item scores. For only ‘item20’ of the BDI, non-clinical group and clinical group differed significantly in the post hoc analysis; however, the subclinical group did not differ significantly from either clinical group or normal participants. The findings are presented in Table 3.

Multivariate Generalized Analysis of Total Scale Scores

Using multivariate analysis of covariance analysis, we investigated whether the scale scores on the BDI, BAI, ATQ, DAS-R, RRS, and WBSI total differed statistically significantly across latent classes after controlling for age and gender. The Bonferroni multiple comparison tests was used to conduct post hoc comparisons. The overall MANCOVA model was found to be significant (Wilks’ λ = 0.164, F (12, 600) = 73.618, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.596). ANCOVA models showed that the BDI (F (2, 305) = 186.337, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.550), BAI (F (2, 305) = 375.777, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.711), ATQ (F (2, 305) = 139.969, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.479), DAS-R (F (2, 305) = 46.770, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.235), RRS (F (2, 305) = 78.188, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.339), and WBSI (F (2, 305) = 36.182, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.192) scores significantly differentiated across subgroups. Considering the effects sizes of cognitive vulnerability factors, the ATQ had the highest eta squared value, followed by the RRS and DAS-R scores, and the WBSI total had the smallest effect size across latent subgroups. Post hoc analysis showed that respondents classified into the Psychopathology subgroup reported higher scores on the BDI and BAI as well as cognitive vulnerability factors of the ATQ, DAS-R, RRS, and WBSI total than subclinical and non-clinical latent classes (p < 0.001). On the other hand, non-clinical subgroup participants reported lower scores on these scales than subclinical and psychopathology subgroups (p < 0.001). The findings are presented in Table 4.

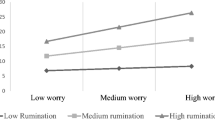

Using multinomial logistic regression analysis, we investigated separate associations of latent classes with age and gender. Age (χ2 (2) = 0.635, p = 0.728) and gender (χ2 (2) = 2.556, p = 0.279) were unsubstantially associated with latent homogenous subgroups. To explore differences in the ATQ, DAS-R, RRS, and WBSI total scores after controlling for age and gender, we run multiple multinomial regression analyses in which three-latent-class was a dependent variable. Demographics (age and gender), the ATQ, DAS-R, RRS, and WBSI total scores regressed onto the latent classes. The multinomial logistic solution showed that the overall model was significant (LRT χ2 (12) = 233.197, p < 0.001), and independent variables accounted for 60.0% of the unique variance of the dependent variable. When considering partial effects after adjusting for age and gender, we found that all vulnerability factors including the ATQ (LRT χ2 (2) = 50.210, p < 0.001), DAS-R (LRT χ2 (2) = 9.942, p < 0.001), RRS (LRT χ2 (2) = 15.675, p < 0.001), and WBSI (LRT χ2 (2) = 14.676, p < 0.001) significantly contributed to the differential patterns of three latent classes. Likelihood ratio tests showed that subjects allocated into the psychopathology subgroup reported higher on the ATQ, DAS-R, RRS, and WBSI than subclinical and nonclinical subgroups. Additionally, the subclinical group also scored higher on these scale scores than the non-clinical group. Findings are represented in Table 5.

Discussion

The present study utilized LCA to explore overlapping and distinct features of depression and anxiety in a sample of community individuals. The latent class solution of the data on item endorsement probability across 21 self-report items of the BDI and 21 self-report items of the BAI showed that three significantly discrepant latent classes of individuals volunteered for the study emerged: (1) psychopathology group, characterized by the high endorsement of depressive states and anxious arousal relative to two other latent classes; (2) subclinical group, characterized by the moderate endorsement of both depression and anxiety symptoms; and (3) normal group, characterized by the low endorsement of depressive and anxious symptomatology.

The categorical mixture analysis results of item responses on the BDI and BAI were consistent with the prior research examining the latent structure of negative affectivity. As previously noted, even though the number of studies was scarce, latent class analysis of depressive and anxious symptomatology has consistently identified three homogenous groups in various samples differing according to the symptom severity across groups rather than the clinical entities (Eaton et al. 1989; Podlogar et al. 2018; Wadsworth et al. 2001). In line with these studies in the literature, a three-latent-class emerged in our non-clinical sample across which severity of individual symptoms of depression and anxiety covariate, suggesting further support for dimensional transdiagnostic models of psychopathology.

In one of few mixture studies of depression and anxiety symptoms carried out in a psychiatric patients group by Podlogar et al. (2018), it was identified that two groups of patients (classes 1 and 2) at some elevated levels of suicidality were more prone to be diagnosed with depression and anxiety disorders; whist, such diagnoses were not discriminant predictors of suicidality. In sharp contrast, having a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder was the unique predictor of the higher suicide-risk. Developmental psychopathology studies showed that depressive and anxious arousal symptoms pursuit different developmental trajectories by gender throughout childhood and adolescence (Cole et al. 1999; Twenge and Nolen-Hoeksema 2002). Sex and age interaction in mood and anxiety symptoms became more salient during adolescence (Bijl et al. 2002; Cairney and Wade 2002; Faravelli et al. 2013). A piece of compelling evidence in the relevant literature has emerged that women are more likely to be diagnosed with major depression than men (Adewuya et al. 2018; Silverstein et al. 2017) and are more prone to score highly on self-administered depression scales (Leach et al. 2008). The same is true for generalized anxiety disorders (Luo et al. 2019), and women are more likely to report greater severity of anxiety than men on self-report measures of anxiety (Leach et al. 2008; Spitzer et al. 2006). However, contrary to epidemiological evidence, Wadsworth et al. (2001) reported similar gender and age patterns across three endorsement profiles of depression and anxiety symptoms among adolescents; however, demographic differences became salient only if the groups were classified according to referral group within latent classes. In keeping with the previous findings, we could not find significant differences in age and gender across symptom endorsement profiles on the current data. A likely account for the discrepancy between these study findings may be that co-occurring symptom endorsement profiles in depression and anxiety may include gender effects. More importantly, comorbidity of distressed self-regulation might be relatively aside from the demographical features. Further research is needed to warrant the tentative influences of demographic variables on co-occurrence profiles of psychiatric symptoms, including clinical and normative samples.

Cognitive models of potential mechanisms unpinning psychopathology and effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) are one of the most investigated issues related to psychotherapy (David et al. 2018; Hayes and Hofmann 2017). Automatic thoughts, dysfunctional beliefs, and ruminative style seem to be hallmarks of mood disorders (Yesilyaprak et al. 2019). Research methodology of CBT randomized clinical trials is suggested to be warranted for further refinements (Cuijpers et al. 2016; Leichsenring and Steinert 2017), whereas cognitive changes are thought to be significantly contributing to symptom elevation, particularly in depression (Lorenzo-Luaces et al. 2015). Despite unsubstantial or relatively less than optimal previous evidence for longitudinal theoretical assumptions of symptom change (Crits-Christoph et al. 2017; Lemmens et al. 2017; Quigley et al. 2019), a randomized trial comparing brief cognitive and mindfulness interventions among 72 patients with major depression showed significant improvement in depressive symptoms of both groups mediated by automatic thoughts of negative-self statements and dysfunctional attitudes towards performance evaluation (Hofheinz et al. 2020). Meta-analyses of psychological risk factors and protective factors among adolescents and college students have consistently identified that automatic thoughts, dysfunctional attitudes, and ruminative response style were significantly associated with depressive symptomatology with largest effect sizes (Liu et al. 2019; Tang et al. 2020). A clinical comparison study across patients with a generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and generalized social phobia (GSP), and health controls showed that MDD group reported higher scores on automatic thoughts than other four groups while controls had lower scores than clinical patients (Gul et al. 2015). Using voxel-based morphometry, Du et al. (2015) indicated that interaction between neuroticism and automatic thoughts, which were linked to the gray matter volume of the parahippocampal gyrus, significantly predicted the depressive symptomatology. A familiar investigation of Beck’s cognitive model among 187 parent-offspring pairs identified that the offspring’s automatic thoughts and dysfunctional attitudes were significant mediators of parent’s negative cognitions and offspring’s depressive symptomatology (Dong and Potenza 2014). Turning on to the studies concerning relationships between cognitive features of anxious arousal symptoms, comparative associations of maladaptive cognitions central to anxiety were observed. Thoughts pertaining to personal failure were identified as a common pathway to both anxiety and depression, while automatic thoughts were more likely tied to anxiety symptoms among youth with autism spectrum disorder (Keefer et al. 2018). Using the mediator structural equation modeling approach, two studies in Japanese participants showed that both positive and negative automatic thoughts mediated the relations between self-compassion and affect (Arimitsu and Hofmann 2015). In comparison to healthy controls, Iancu et al. (2015) observed that patients with a social anxiety disorder had greater scores of negative automatic thoughts and depression.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study would be a preliminary to address the unique associations of transdiagnostic factors with homogenous respondent groups at some elevated levels of depressive and anxious symptomatology identified using mixture analysis. Considering correlations between the variables in question, we identified moderate to strong correlations of transdiagnostic factors of psychopathology in terms of the ATQ, DAS-R, RRS, and WBSI with the BDI and BAI total scores. However, more importantly, all of these four transdiagnostic factors (ATQ, DAS-R, RRS, and WBSI) suggested as a psychological vulnerability in distress disorders were demonstrated to be crucially associated with latent homogenous groups after controlling for age and gender through multivariate linear and mixture modeling approaches. We found an immense effect size for the ATQ and large effect sizes for the DAS-R, RRS, and WBSI for the differences in total scale scores across latent profiles of depression and anxiety. Our findings were partially in contrast with some previous data that, despite the paucity of studies on the transdiagnostic characteristic of the ATQ and DAS, Hill et al. (1989) substantiated the content specificity of ATQ with depression compared to DAS scores which had been put forward by Hollon et al. (1986) in advance. It is worth noting that both measures were found to covarying with syndrome rather nosological depression, a point made by Hollon et al. (1986). More recent studies identified automatic thoughts as a significant risk factor for the formation and perseverance of depression rather than anxiety symptoms (Gul et al. 2015; Keefer et al. 2018) even though these studies are not without contradictory evidence (Arimitsu and Hofmann 2015). Additionally, it appeared that specific automatic thoughts might be differentially associated with depression and anxiety symptoms (Buschmann et al. 2018). In the current scrutiny, the most substantial variance across latent profiles of depression and anxiety endorsement was accounted for by the ATQ total scores, followed by the RRS. A potential reason for this discrepancy may be sample characteristics that the previous studies were carried out in clinical samples, whereas our data consisted of a normative sample of college students. More importantly, both psychological constructs initially developed to assess maladaptive cognitions in depression seem to be significant correlates of a general distress factor in distress disorders, suggesting further evidence for tripartite model of emotion regulation (Boysan 2019; Watson 2009).

In a meta-analytic review of cognitive emotional regulation strategies in relation to clinical conditions by Aldao et al. (2010), of various regulation strategies, ruminative responses and thought suppression were significantly and positively associated with severity of psychopathology in terms of anxiety and depression with the former had a large and the latter had a medium effect size. A strong point made by the analysis was that presence of a maladaptive emotional regulation strategy was more detrimental than the deprivation of adaptive emotional regulation strategies with more robust associations in clinical groups compared to normative samples. In keeping with the prospect, it was found that, in comparison to non-use of more adaptive strategies of reappraisal and problem solving, the use of maladaptive cognitive regulation strategies of rumination and thought suppression was found to be playing a central role in psychopathology (Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema 2010). A prospective study of interactions between the use of adaptive cognitive emotional strategies such as reappraisal and acceptance and maladaptive strategies such as rumination, suppression, and avoidance with psychopathology (depression, anxiety, and alcohol abuse) reported that significant associations of adaptive strategies with psychopathology were moderated concurrently by maladaptive strategies. However, either alone or interacting with maladaptive strategies, adaptive regulation strategies exert no significant prospective influence on psychopathology in a transdiagnostic manner (Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema 2012).

More recent investigations have consistently confirmed the significant linkages between rumination, depression, and anxiety (H. M. Brown et al. 2016; Kalmbach et al. 2016; Merino et al. 2016; Yilmaz 2015). In a large community adult sample, Parmentier et al. (2019) identified that rumination and worry were the most prominent mediators of the relationships of mindfulness with depression and anxiety, whereas thought suppression was tied only depressive symptomatology but not anxious arousal. Rumination was a significant mediator between negative affect and depression but not anxiety symptoms in a sample of psychiatric patients (Iqbal and Dar 2015). Ruminative thinking was linked to impulsive behaviors in the context of anxiety, on the other hand, rumination contributed to amotivation in the context of depression in a non-clinical college sample (Riley et al. 2019). However, significant relationships between childhood traumatic experiences and depression/anxiety were mediated by rumination, the effect of which was prominent in females (Kim et al. 2017). Rumination seems to be playing a transdiagnostic role in relations between sleep and affect (Armstead et al. 2019). Elevated anxiety and depression symptoms in relation to rumination were found to be a significant contributing factor for sleep problems (Thorsteinsson et al. 2019). Deficits in attentional control were significantly tied to both depressive and anxious symptomatology in which the significant linkage was mediated by rumination (Hsu et al. 2015). Interaction between high levels of brooding rumination and low levels of interceptive awareness was a significant determinant of elevated depressive and anxious symptoms in a community college sample (Lackner and Fresco 2016). Current data provided further support and expanded the preliminary results germane to the role of these transdiagnostic factors in emotional dysregulation that both rumination and thought suppression was significantly tied to endorsement profiles of depression and anxiety symptoms with rumination had a larger effect size.

This study was challenged by several drawbacks, which may be suggestive of potential directions in future research. First and foremost, given that the normative sample was recruited from a university with the sample size was relatively small, replication of these findings should be warranted in psychiatric samples with various clinical diagnoses. Second, the study procedure mainly relied on self-report measures of anxious and depressive symptomatology. Structured clinical interviews such as the SCID for DSM-5 (First et al. 2016) might have yielded different latent class solutions and relevant associations. Finally, the cross-sectional study design limited the generalizability of findings as well as causal inferences on the current data. Using longitudinal research design, it should be warranted whether transdiagnostic factors such as automatic thoughts, dysfunctional attitudes, ruminative response style, and thought suppression operate cumulatively or temporal precedence exists across the vulnerability factors in question in the formation and perseverance of distress disorders such as depression and anxiety.

References

Abramowitz, J. S., Tolin, D. F., & Street, G. P. (2001). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression: A meta-analysis of controlled studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(5), 683–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00057-X.

Adewuya, A. O., Coker, O. A., Atilola, O., Ola, B. A., Zachariah, M. P., Adewumi, T., Olugbile, O., Fasawe, A., & Idris, O. (2018). Gender difference in the point prevalence, symptoms, comorbidity, and correlates of depression: Findings from the Lagos state mental health survey (LSMHS), Nigeria. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 21(6), 591–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0839-9.

Aldao, A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2010). Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: A transdiagnostic examination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(10), 974–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002.

Aldao, A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). When are adaptive strategies most predictive of psychopathology? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(1), 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023598.

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004.

Altin, M., & Gencoz, T. (2009). Psychopathological correlates and psychometric properties of the White bear suppression inventory in a Turkish sample. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.25.1.23.

Arimitsu, K., & Hofmann, S. G. (2015). Cognitions as mediators in the relationship between self-compassion and affect. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.008.

Armstead, E. A., Votta, C. M., & Deldin, P. J. (2019). Examining rumination and sleep: A transdiagnostic approach to depression and social anxiety. Neurology Psychiatry and Brain Research, 32, 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npbr.2019.05.003.

Bagby, R. M., Rector, N. A., Bacchiochi, J. R., & McBride, C. (2004). The stability of the response styles questionnaire rumination scale in a sample of patients with major depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28(4), 527–538. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:Cotr.0000045562.17228.29.

Batmaz, S., & Ozdel, K. (2016). Psychometric properties of the revised and abbreviated form of the Turkish version of the dysfunctional attitude scale. Psychological Reports, 118(1), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294116628349.

Beck, A. T. (1996). Beyond belief: A theory of modes, personality, and psychopathology. In P. M. Salkovskis (Ed.), Frontiers of cognitive therapy (pp. 1–25). New York: Guilford Press.

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Beck, A. T., & Bredemeier, K. (2016). A unified model of depression: Integrating clinical, cognitive, biological, and evolutionary perspectives. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(4), 596–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702616628523.

Beck, A. T., & Clark, D. A. (1997). An information processing model of anxiety: Automatic and strategic processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00069-1.

Beck, A. T., & Haigh, E. A. (2014). Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734.

Beck, A. T., Rush, J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guildford Press.

Beck, A. T., Brown, G., Epstein, N., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893–897. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.56.6.893.

Bijl, R. V., De Graaf, R., Ravelli, A., Smit, F., & Vollebergh, W. A. (2002). Gender and age-specific first incidence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the general population. Results from the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 37(8), 372–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-002-0566-3.

Blagden, J. C., & Craske, M. G. (1996). Effects of active and passive rumination and distraction: A pilot replication with anxious mood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 10(4), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/0887-6185(96)00009-6.

Bowman, M. A., Cunningham, T. J., Levin-Aspenson, H. F., O'Rear, A. E., Pauszek, J. R., Ellickson-Larew, S., ... Payne, J. D. (2019). Anxious, but not depressive, symptoms are associated with poorer prospective memory performance in healthy college students: Preliminary evidence using the tripartite model of anxiety and depression. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 41(7), 694–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2019.1611741.

Boysan, M. (2019). An integration of quadripartite and helplessness-hopelessness models of depression using the Turkish version of the learned helplessness scale (LHS). British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2019.1612033.

Brown, T. A., Campbell, L. A., Lehman, C. L., Grisham, J. R., & Mancill, R. B. (2001). Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(4), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.585.

Brown, H. M., Meiser-Stedman, R., Woods, H., & Lester, K. J. (2016). Cognitive vulnerabilities for depression and anxiety in childhood: Specificity of anxiety sensitivity and rumination. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 44(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465814000472.

Buschmann, T., Horn, R. A., Blankenship, V. R., Garcia, Y. E., & Bohan, K. B. (2018). The relationship between automatic thoughts and irrational beliefs predicting anxiety and depression. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-017-0278-y.

Cairney, J., & Wade, T. J. (2002). The influence of age on gender differences in depression: Further population-based evidence on the relationship between menopause and the sex difference in depression. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 37(9), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-002-0569-0.

Calmes, C. A., & Roberts, J. E. (2007). Repetitive thought and emotional distress: Rumination and worry as prospective predictors of depressive and anxious symptomatology. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 31(3), 343–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9026-9.

Celeux, G., & Soromenho, G. (1996). An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification, 13(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/Bf01246098.

Clark, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (2011a). The anxiety and worry workbook: The cognitive behavioral solution. New York: Guilford Press.

Clark, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (2011b). Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders: Science and practice. New York: Guilford Press.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.100.3.316.

Clark, D. A., Steer, R. A., & Beck, A. T. (1994). Common and specific dimensions of self-reported anxiety and depression: Implications for the cognitive and tripartite models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103(4), 645–654.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd edition). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., Peeke, L. A., Seroczynski, A. D., & Fier, J. (1999). Children's over- and underestimation of academic competence: A longitudinal study of gender differences, depression, and anxiety. Child Development, 70(2), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00033.

Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2013). Latent class and latent transition analysis with applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Hoboken: Wiley.

Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., Walker, J. R., Kjernisted, K., & Pidlubny, S. R. (2001). Psychological vulnerabilities in patients with major depression vs panic disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39(5), 567–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00027-9.

Crits-Christoph, P., Gallop, R., Diehl, C. K., Yin, S., & Gibbons, M. B. C. (2017). Mechanisms of change in cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder in the community mental health setting. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(6), 550–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000198.

Cuijpers, P., Cristea, I. A., Karyotaki, E., Reijnders, M., & Huibers, M. J. H. (2016). How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta-analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry, 15(3), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20346.

David, D., Cristea, I., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004.

DeJong, H., Fox, E., & Stein, A. (2016). Rumination and postnatal depression: A systematic review and a cognitive model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 82, 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.05.003.

Dong, G., & Potenza, M. N. (2014). A cognitive-behavioral model of internet gaming disorder: Theoretical underpinnings and clinical implications. Journal of Psychiatry Research, 58, 7–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.005.

Du, X., Luo, W. B., Shen, Y. M., Wei, D. T., Xie, P., Zhang, J. F., ... Qiu, J. (2015). Brain structure associated with automatic thoughts predicted depression symptoms in healthy individuals. Psychiatry Research-Neuroimaging, 232(3), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.03.002.

Eaton, W. W., McCutcheon, A., Dryman, A., & Sorenson, A. (1989). Latent class analysis of anxiety and depression. Sociological Methods & Research, 18(1), 104–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189018001004.

Ehring, T., & Watkins, E. R. (2008). Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1(3), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2008.1.3.192.

Erdur-Baker, Ö., & Bugay, A. (2012). The Turkish version of the ruminative response scale: An examination of its reliability and validity. The International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 1–16.

Faravelli, C., Alessandra Scarpato, M., Castellini, G., & Lo Sauro, C. (2013). Gender differences in depression and anxiety: The role of age. Psychiatry Research, 210(3), 1301–1303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.09.027.

First, M. B., Williams, J. B., Karg, R. S., & Spitzer, R. L. (2016). Structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders: SCID-5-CV clinician version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Goodwin, G. M. (2015). The overlap between anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(3), 249–260.

Gul, A. I., Simsek, G., Karaaslan, O., & Inanir, S. (2015). Comparison of automatical thoughts among generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder and generalized social phobia patients. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 19(15), 2916–2921.

Haraden, D. A., Mullin, B. C., & Hankin, B. L. (2019). Internalizing symptoms and chronotype in youth: A longitudinal assessment of anxiety, depression and tripartite model. Psychiatry Research, 272, 797–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.117.

Hartlage, S., Alloy, L. B., Vazquez, C., & Dykman, B. (1993). Automatic and effortful processing in depression. Psychological Bulletin, 113(2), 247–278. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.113.2.247.

Harvey, A. G., Watkins, E., Mansell, W., & Shafran, R. (2004). Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders: A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hasegawa, A., Kunisato, Y., Morimoto, H., Nishimura, H., & Matsuda, Y. (2018). How do rumination and social problem solving intensify depression? A longitudinal study. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 36(1), 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-017-0272-4.

Hayes, S. C., & Hofmann, S. G. (2017). The third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy and the rise of process-based care. World Psychiatry, 16(3), 245–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20442.

He, Y. N., Song, N., Xiao, J., Cui, L. X., & McWhinnie, C. M. (2018). Levels of neuroticism differentially predict individual scores in the depression and anxiety dimensions of the tripartite model: A multiwave longitudinal study. Stress and Health, 34(3), 435–439. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2803.

Hill, C. V., Oei, T. P. S., & Hill, M. A. (1989). An empirical investigation of the specificity and sensitivity of the automatic thoughts questionnaire and dysfunctional attitudes scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 11(4), 291–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00961529.

Hisli, N. (1989). The validity and reliability of the Beck depression inventory among university students. Turkish Journal of Psychology, 7, 3–13.

Hofheinz, C., Reder, M., & Michalak, J. (2020). How specific is cognitive change? A randomized controlled trial comparing brief cognitive and mindfulness interventions for depression. Psychotherapy Research, 30(5), 675–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1685138.

Hofmeijer-Sevink, M. K., Batelaan, N. M., van Megen, H. J. G. M., Penninx, B. W., Cath, D. C., van den Hout, M. A., & van Balkom, A. J. L. M. (2012). Clinical relevance of comorbidity in anxiety disorders: A report from the Netherlands study of depression and anxiety (NESDA). Journal of Affective Disorders, 137(1–3), 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.008.

Hollon, S. D., & Kendall, P. C. (1980). Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 4(4), 383–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/Bf01178214.

Hollon, S. D., Kendall, P. C., & Lumry, A. (1986). Specificity of depressotypic cognitions in clinical depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(1), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.95.1.52.

Hong, R. Y., & Cheung, M. W. L. (2014). The structure of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression and anxiety. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(6), 892–912. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614553789.

Hsu, K. J., Beard, C., Rifkin, L., Dillon, D. G., Pizzagalli, D. A., & Bjorgvinsson, T. (2015). Transdiagnostic mechanisms in depression and anxiety: The role of rumination and attentional control. Journal of Affective Disorders, 188, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.008.

Iancu, I., Bodner, E., Joubran, S., Lupinsky, Y., & Barenboim, D. (2015). Negative and positive automatic thoughts in social anxiety disorder. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 52(2), 129–136.

IBM Corporation. (2015). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 23.0. Armonk: IBM Corporation.

Iqbal, N., & Dar, K. A. (2015). Negative affectivity, depression, and anxiety: Does rumination mediate the links? Journal of Affective Disorders, 181, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.002.

Jenkins, P. E., Ducker, I., Gooding, R., James, M., & Rutter-Eley, E. (2020). Anxiety and depression in a sample of UK college students: A study of prevalence, comorbidity, and quality of life. Journal of American College Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2019.1709474.

Jones, N. P., Fournier, J. C., & Stone, L. B. (2017). Neural correlates of autobiographical problem-solving deficits associated with rumination in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 218, 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.069.

Kaiser, R. H., Snyder, H. R., Goer, F., Clegg, R., Ironside, M., & Pizzagalli, D. A. (2018). Attention bias in rumination and depression: Cognitive mechanisms and brain networks. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(6), 765–782. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618797935.

Kaiser, R. H., Kang, M. S., Lew, Y., Van Der Feen, J., Aguirre, B., Clegg, R., ... Pizzagalli, D. A. (2019). Abnormal frontoinsular-default network dynamics in adolescent depression and rumination: A preliminary resting-state co-activation pattern analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44(9), 1604–1612. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0399-3.

Kalmbach, D. A., Pillai, V., & Ciesla, J. A. (2016). The correspondence of changes in depressive rumination and worry to weekly variations in affective symptoms: A test of the tripartite model of anxiety and depression in women. Australian Journal of Psychology, 68(1), 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12090.

Keefer, A., Kreiser, N. L., Singh, V., Blakeley-Smith, A., Reaven, J., & Vasa, R. A. (2018). Exploring relationships between negative cognitions and anxiety symptoms in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Therapy, 49(5), 730–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.12.002.

Kessler, R. C., Nelson, C. B., McGonagle, K. A., Liu, J., Swartz, M., & Blazer, D. G. (1996). Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: Results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. British Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1192/S0007125000298371.

Kessler, R. C., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Wittchen, H. U. (2012). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1359.

Kim, J. S., Jin, M. J., Jung, W., Hahn, S. W., & Lee, S. H. (2017). Rumination as a mediator between childhood trauma and adulthood depression/anxiety in non-clinical participants. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01597.

Kirkegaard Thomsen, D. (2006). The association between rumination and negative affect: A review. Cognition & Emotion, 20(8), 1216–1235. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930500473533.

Koster, E. H. W., De Lissnyder, E., Derakshan, N., & De Raedt, R. (2011). Understanding depressive rumination from a cognitive science perspective: The impaired disengagement hypothesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.005.

Krys, S., Otte, K. P., & Knipfer, K. (2020). Academic performance: A longitudinal study on the role of goal-directed rumination and psychological distress. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 33, 545–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1763141.

Lackner, R. J., & Fresco, D. M. (2016). Interaction effect of brooding rumination and interoceptive awareness on depression and anxiety symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 85, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.08.007.

Leach, L. S., Christensen, H., Mackinnon, A. J., Windsor, T. D., & Butterworth, P. (2008). Gender differences in depression and anxiety across the adult lifespan: The role of psychosocial mediators. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(12), 983–998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0388-z.

Leichsenring, F., & Steinert, C. (2017). Is cognitive behavioral therapy the gold standard for psychotherapy? The need for plurality in treatment and research. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association, 318(14), 1323–1324. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.13737.

Lemmens, L. H. J. M., Galindo-Garre, F., Arntz, A., Peeters, F., Hollon, S. D., DeRubeis, R. J., & Huibers, M. J. H. (2017). Exploring mechanisms of change in cognitive therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for adult depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 94, 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.005.

Liu, Y., Zhang, N., Bao, G. Y., Huang, Y. B., Ji, B. Y., Wu, Y. L., ... Li, G. Y. (2019). Predictors of depressive symptoms in college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 244, 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.084.

Lo, Y. T., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/88.3.767.

Lorenzo-Luaces, L., German, R. E., & DeRubeis, R. J. (2015). It's complicated: The relation between cognitive change procedures, cognitive change, and symptom change in cognitive therapy for depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 41, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.12.003.

Luo, Z. C., Li, Y. Q., Hou, Y. T., Liu, X. T., Jiang, J. J., Wang, Y., ... Wang, C. J. (2019). Gender-specific prevalence and associated factors of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in a Chinese rural population: The Henan rural cohort study. BMC Public Health, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8086-1.

Lyubomirsky, S., Layous, K., Chancellor, J., & Nelson, S. K. (2015). Thinking about rumination: The scholarly contributions and intellectual legacy of Susan Nolen-Hoeksema. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112733.

Magee, J. C., & Zinbarg, R. E. (2007). Suppressing and focusing on a negative memory in social anxiety: Effects on unwanted thoughts and mood. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(12), 2836–2849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.05.003.

Magee, W. J., Eaton, W. W., Wittchen, H. U., McGonagle, K. A., & Kessler, R. C. (1996). Agoraphobia, simple phobia, and social phobia in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53(2), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830020077009.

Magee, J. C., Harden, K. P., & Teachman, B. A. (2012). Psychopathology and thought suppression: A quantitative review. Clincal Psychology Review, 32(3), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.001.

Mansell, W., Harvey, A., Watkins, E. R., & Shafran, R. (2008). Cognitive behavioral processes across psychological disorders: A review of the utility and validity of the transdiagnostic approach. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1(3), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2008.1.3.181.

Mathew, A. R., Pettit, J. W., Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., & Roberts, R. E. (2011). Comorbidity between major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders: Shared etiology or direct causation? Psychological Medicine, 41(10), 2023–2034. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711000407.

McLaughlin, K. A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2011). Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(3), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006.

McLaughlin, K. A., Borkovec, T. D., & Sibrava, N. J. (2007). The effects of worry and rumination on affect states and cognitive activity. Behavior Therapy, 38(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.03.003.

McNally, R. J. (1995). Automaticity and the anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(7), 747–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(95)00015-p.

Merino, H., Senra, C., & Ferreiro, F. (2016). Are worry and rumination specific pathways linking neuroticism and symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder and mixed anxiety-depressive disorder? PLoS One, 11(5), e0156169. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156169.

Miller, M. E., Borowski, S., & Zeman, J. L. (2020). Co-rumination moderates the relation between emotional competencies and depressive symptoms in adolescents: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(6), 851–863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00643-6.

Muris, P., Roelofs, J., Meesters, C., & Boomsma, P. (2004). Rumination and worry in nonclinical adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28(4), 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COTR.0000045563.66060.3e.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2006). MPlus User's Guide, (4th ed). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Najmi, S., & Wegner, D. M. (2008). Mental control: Thought suppression and psychopathology. In A. J. Elliot (Ed.), Handbook of approach and avoidance motivation (pp. 447–459). New York: Psychology Press.

Najmi, S., & Wegner, D. M. (2009). Hidden complications of thought suppression. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 2(3), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2009.2.3.210.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504.

Nolenhoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective-study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma-Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Parker, L. E., & Larson, J. (1994). Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.1.92.

Norton, S., Cosco, T., Doyle, F., Done, J., & Sacker, A. (2013). The hospital anxiety and depression scale: A meta confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 74(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.10.010.

Nylund, K. L., Asparoutiov, T., & Muthen, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling-a Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396.

Olatunji, B. O., Naragon-Gainey, K., & Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B. (2013). Specificity of rumination in anxiety and depression: A multimodal meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20(3), 225–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12037.

Ozdel, K., Taymur, I., Guriz, S. O., Tulaci, R. G., Kuru, E., & Turkcapar, M. H. (2014). Measuring cognitive errors using the cognitive distortions scale (CDS): Psychometric properties in clinical and non-clinical samples. PLoS One, 9(8), e105956. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105956.

Parmentier, F. B. R., Garcia-Toro, M., Garcia-Campayo, J., Yanez, A. M., Andres, P., & Gili, M. (2019). Mindfulness and symptoms of depression and anxiety in the general population: The mediating roles of worry, rumination, reappraisal and suppression. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00506.

Podlogar, M. C., Rogers, M. L., Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Chiurliza, B., & Joiner, T. E. (2018). Anxiety, depression, and the suicidal spectrum: A latent class analysis of overlapping and distinctive features. Cognition and Emotion, 32(7), 1464–1477. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1303452.

Price, M., Legrand, A. C., Brier, Z. M. F., & Hebert-Dufresne, L. (2019). The symptoms at the center: Examining the comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and depression with network analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 109, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.11.016.

Purdon, C. (1999). Thought suppression and psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37(11), 1029–1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00200-9.

Quigley, L., Dozois, D. J. A., Bagby, R. M., Lobo, D. S. S., Ravindran, L., & Quilty, L. C. (2019). Cognitive change in cognitive-behavioural therapy v. pharmacotherapy for adult depression: A longitudinal mediation analysis. Psychological Medicine, 49(15), 2626–2634. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718003653.

Ramaswamy, V., Desarbo, W. S., Reibstein, D. J., & Robinson, W. T. (1993). An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science, 12(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.12.1.103.

Rassin, E., Merckelbach, H., & Muris, P. (2000). Paradoxical and less paradoxical effects of thought suppression: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(8), 973–995. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00019-7.

Renaud, J. M., & McConnell, A. R. (2002). Organization of the self-concept and the suppression of self-relevant thoughts. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2001.1485.

Ricarte, J. J., Ros, L., Fernandez, D., Nieto, M., & Latorre, J. M. (2018). Effects of analytical (abstract) versus experiential (concrete) induced rumination of negative self defining memories on schizotypic symptoms. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 59(5), 553–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12464.

Riley, K. E., Cruess, D. G., Park, C. L., Tigershtrom, A., & Laurenceau, J. P. (2019). Anxiety and depression predict the paths through which rumination acts on behavior: A daily diary study. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 38(5), 409–426. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2019.38.5.409.

Routledge, K. M., Burton, K. L. O., Williams, L. M., Harris, A., Schofield, P. R., Clark, C. R., & Gatt, J. M. (2017). The shared and unique genetic relationship between mental well-being, depression and anxiety symptoms and cognitive function in healthy twins. Cognition & Emotion, 31(7), 1465–1479. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1232242.