Abstract

Although coping plays an important role in human adaptation, surprisingly little is known about coping processes in emerging adults. This study examined the structure and function of coping in emerging adults. Using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), this study examined whether there is support for the ‘coping families’ framework, as outlined by Skinner and colleagues (Skinner et al. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216-269 2003). A total of 425 individuals (63.5% female), aged 18–31 years (M age 25.04 years), were recruited online through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) to complete questionnaires on demographic information, mental health, substance use behaviors, competence, and coping behaviors in response to an interpersonal problem. EFA results yielded partial support for the coping families approach in that support-seeking and problem-solving emerged as robust factors. Further, bivariate correlations suggested that coping behaviors previously associated with adaptive functioning were linked with well-being and competence, whereas coping behaviors previously associated with maladaptive functioning were significantly associated with negative outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In his seminal work on emerging adulthood, Arnett (2000, 2006) suggests that the years between 18 and 29 are theoretically and empirically different from prior and ensuing ages. Emerging adults commonly experience frequent changes in educational status, relationships, occupation, and residence; these lifestyle characteristics can result in an lifestyle for this developmental group that is less stable compared to prior and later periods (Arnett 2000; Arnett et al. 2014). As such, it is not surprising that emerging adults report high levels of stress (American College Health Association 2006; Asberg et al. 2008; Pierceall and Keim 2007). One study that recruited a multiethnic sample of college students suggested that this emerging adult sample experienced stress in several areas, including academic (28.4%), social (peers: 20.7%; family: 17.5%), and financial (6.8%) domains (Aldridge-Gerry et al. 2011). Further, high rates of mental health disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, substance use) are reported by emerging adults (American College Health Association 2006; Eisenberg et al. 2007; Kessler et al. 2005; Kessler and Wang 2008).

Given that emerging adults experience high levels of stress across several domains, scholars have examined coping responses of this age group. Coping can be defined as “action regulation under stress, which includes coordination, mobilization, energizing, directing and guiding behaviors, emotion and orientation when responding to stress” (Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2014, p. 65). Coping responses occur daily in individuals of all ages, and these behaviors are fundamental to human adaptation, such as psychological well-being, academic performance, and physical health (Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016; Thompson et al. 2010). Coping may play an important role in buffering the association between stress and maladaptation (e.g., Compas and Reeslund 2009; Curtis and Cicchetti 2007; Jaser and White 2011). Despite the importance of coping across the lifespan, surprisingly little is currently known about the normative development of coping (Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016). Given that increased levels of stress are often reported by emerging adults (Coccia and Darling 2016; Pierceall and Keim 2007), it is of particular interest to understand how this segment of the population responds to stress.

Meaningful progress in the aggregation of knowledge on the development of coping appears to have been hampered by two main factors. First, much of the coping research has examined individual differences in coping within a narrow age group (e.g., examining how aspects of coping are related to adjustment); few investigations to date have explicitly examined changes in coping that may occur within or across developmental periods (Compas et al. 2014; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016; Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011). Second, progress in this area has also been hampered by the lack of consensus on how to define and measure coping across development (e.g., Blount et al. 2008; Compas et al, 2001). Knowledge of normative age-graded changes in coping can inform not only researchers on what aspects of coping to measure at a given developmental period, but also clinicians on how to intervene (Compas et al. 2014).

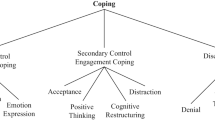

In an attempt to address some of the noted shortcomings in the conceptualization and assessment of coping, Skinner et al. (2003) suggested the ‘12 coping families’ framework. The ‘12 coping families’ describe the most common ways in which individuals of different ages respond to stress (i.e., the behavioral and cognitive coping responses that occur in response to stress; Skinner et al. 2003). For example, an individual who reaches out to a friend for support after a stressful day at work would be using the coping response ‘support seeking.’ This hierarchical system of coping was established based on the authors’ comprehensive review of coping research using a range of methodologies, including exploratory factors analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and rational sorting (Skinner et al. 2003). The 12 coping families describe a wide range of coping responses, including: problem-solving, information seeking, self-reliance, support-seeking, accommodation, negotiation, delegation, isolation, helplessness, escape, submission, and opposition (Skinner et al. 2003). These reflect a comprehensive list of potential coping responses that the authors argue represent “functionally homogeneous” ways of coping (Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011, p. 3). This list is deemed to be useful in that it provides a “comprehensive menu of coping options” for the study of coping with different types of stress that occur at different ages (Skinner et al. 2013, p. 807).

Scholars have discouraged the use of labels, such as ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ when describing coping families as this view is too simplistic (Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2008). Nevertheless, it appears that some coping families are more frequently associated with well-being and adaptation than others. For example, support-seeking, problem- solving, and accommodation have been linked in prior research to positive developmental outcomes (Skinner et al. 2013; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016). In contrast, empirical evidence suggests that other coping responses, such as escape, submission, and opposition, are often linked to maladaptation (Skinner et al. 2013; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016).

Based on theoretical and empirical work, the present study focused on six of the twelve coping families. In their review of the coping literature, Skinner and colleagues identified four coping families that are “clearly core” (Skinner et al. 2003, p. 239); they include problem-solving, support-seeking, escape, and accommodation. Beyond this, two additional coping families—submission and isolation—were included in this study as they are particularly relevant to the developmental period of emerging adulthood. Prior research suggests that ruminative thinking, a core aspect of submission, occurs at higher rates in 25–35-year-olds than in older adults (Nolen-Hoeksema and Aldao 2011). Further, emerging adults gain independence from their family during this developmental stage and, as a key developmental task, form new social and intimate relationships (Arnett 2000, 2006). It is therefore highly relevant to assess whether, and to what degree, emerging adults are using coping behaviors included in the two coping families of submission and isolation.

The coping families framework has been used to study the normative development of coping. For example, an integrative review of 62 developmental studies on coping used the framework of the 12 coping families to identify age-related shifts in coping (Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016; Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011). Results from this analysis led authors to conclude that “broad global age-related differences and changes” occur, such that coping becomes more differentiated, consolidated, and flexible (Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011, p. 54). For example, sophisticated coping responses that involve decision-making, planning, and reflection, were found to emerge later in development (i.e., adolescence or early adulthood; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016). However, this review of developmental research on coping using the 12 coping families framework did not extend beyond adolescence. As such, little is currently known about the structure of coping in emerging adults. A further gap in the current knowledge base pertains to links between coping and adaptation. Some research has elucidated associations between emerging adult coping and adaptation, such as adjustment to college (Feenstra et al. 2001) and resilience (Galatzer-Levy et al. 2012); however, the majority of existing research has focused on negative outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, physical health problems, and substance use (e.g., Coiro et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2014; Park et al. 2004).

The Current Study

This study sought to fill gaps in the literature by examining the structure (Aim 1) and function (Aim 2) of coping in emerging adults. Regarding Aim 1, the goal was to uncover the underlying structure of several coping behaviors to ascertain similarities and differences between coping in emerging adulthood and earlier developmental periods. Based on existing theoretical and empirical data that was reviewed in the foregoing sections, EFA analyses was expected to yield support for six coping families (as described above) in emerging adults (Hypothesis 1). Further, it was expected that coping families previously associated with adaptation would be associated with psychological well-being and competence, while coping families previously associated with maladaptation would be linked to psychological distress and substance use (Hypothesis 2).

Method

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the authors’ institution. Participants were recruited online via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) to complete all questionnaires as part of a larger study of emerging adult development. MTurk is a popular online crowdsourcing application used in the social sciences (Chandler et al. 2014). Participants select Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs) of interest and are compensated for their work (for a comprehensive review of MTurk see Chandler and Shapiro 2016). Prior research indicates that MTurk samples are significantly more diverse with regard to race, socioeconomic background, and educational status than are college samples (e.g., Buhrmester et al. 2011; Casler et al. 2013). With regard to reliability and validity, MTurk data is comparable to data that is collected via traditional methodology (Buhrmester et al. 2011; Shapiro et al. 2013).

Data collection occurred through the online survey platform Qualtrics, which was accessible to participants from a private computer or laptop. To ensure that responses were not provided randomly, six attention check items were included in the survey (e.g., “Please select the Never response option”). Attention checks are commonly used on online survey research to identify and exclude careless participants (Kung et al. 2018). Twenty-seven participants were excluded from the study due to failing more than one of the six attention checks. Following guidelines put forth by Eysenbach (2004), 18 participants were removed from the study due to completing the survey in under five minutes (each participant was asked to complete a total of 161 items and a completion time of under five minutes was deemed to be reflect an atypical timestamp; see Eysenbach 2004 for guidelines).

Participants

The final working sample included 425 participants. Independent samples t-tests suggested that excluded participants (n = 45) did not differ significantly from included participants (n = 425) on age or socioeconomic status. Chi square tests of independence suggested that significant group differences emerged for gender such that males were more likely to be excluded than any other gender identity. However, the excluded group did not differ from the non-excluded group with regard to ethnicity or education. The final sample included participants between the ages of 18–31Footnote 1 years (M age = 25.04, SD = 2.68). Two-hundred and seventy participants identified as female (63.5%), 152 participants identified as male (35.8%), and three participants identified as “other” gender (0.3%). Participants identified as White (68.4%), Black (11.3%), Hispanic (9.9%), Asian (6.1%), Biracial (2.6%), American Indian (0.7%), and Other (1%). The median reported household income in the present study was $23,000.

Measures

Demographics

Participants provided demographic information, including age, gender, racial/ethnic identity, socioeconomic status (SES), highest level of education completed, current educational status, and current employment status.

Coping

Participants completed 26 items on coping. These items were selected from existing measures for the present study after reviewing the literature and consulting with experts in the field. The use of an already-existing coping scale was not possible because no study to date assessed the six coping families in an emerging adult sample, As such, 26 items were selected to assess the following six coping families: support-seeking, problem-solving, accommodation, escape, submission, and isolation. Table 1 includes detailed information on each of the 26 items used in this study and describes which existing measure each item was taken from. These six coping families were chosen based on a review of extant literature (e.g., Skinner et al. 2003; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016; Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2008; Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011) as well as their relevance to the developmental period of emerging adulthood. Whereas support-seeking, problem-solving, and accommodation have most commonly been linked to adaptation, escape, submission, and isolation have been linked to less desirable outcomes (Skinner et al. 2013; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016). Each coping family was assessed with four or five items, using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all; 1 = a little; 2 = some; 3 = a lot). Question stems were modified to ensure consistency across items (e.g., the question stem was changed from “I would work on…” to “You worked on…”). The following prompt was used to assess participants’ coping response: “When you had interpersonal problems in the last month (e.g., arguing with a friend/parent, fighting with a romantic partner, having a conflict with a coworker), please indicate how often you did the following.” Prior work suggests that such a situation-specific approach to coping is more reliable than a dispositional approach (Lazarus 1999; Todd et al. 2004). Given that much prior work on coping has examined responses to interpersonal stress (e.g., Clarke 2006; Coiro et al. 2017; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2009) and emerging adults report high levels of stress in interpersonal domains (Aldridge-Gerry et al. 2011; Dusselier et al. 2005), participants were asked to report their coping responses for interpersonal stress.

Well-Being

The Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF; Keyes 2002; Keyes et al. 2008) was used to assess well-being (i.e., emotional, social, and psychological adjustment). Respondents were asked to reflect on the past month and to indicate how often they experienced certain signs of well-being. The MHC-SF includes 14 total items (three items for emotional well-being; five items for social well-being; six items for psychological well-being), using a 6-point Likert scale. Example items include: “How often did you feel happy?”, “How often did you feel good at managing the responsibilities of your daily life?” In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha value for the MHC-SF was .93.

Competence

Competence was assessed using a modified version of the Self-Perception Profile for College Students (SPPCS; Harter 2012). The three specific domains of romantic relationships, parent relationship, and social acceptance were assessed. Participants choose one response option for each statement (describes me very poorly, describes me quite poorly, describes me quite well, describes me very well; Wichstrom 1995). Example items are “I am able to develop romantic relationships” (Harter Romantic), “I am able to get along with my parents quite well” (Harter Parent), and “I am able to make new friends easily” (Harter Social). Higher scores reflect greater levels of competence. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha values for the three Harter subscales ranged between .91 and .93.

Psychological Distress

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale, Short Form (DASS-21; Lovidbond and Lovibond 1995) was used to assess psychological distress, including depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and perceived levels of stress. Respondents indicate on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from did not apply to me at all to applied to me very much, or most of the time, how much 21 items reflected their experiences. Example items include “I felt that I had nothing to look forward to” and “I found it difficult to relax.” This measure has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties (Crawford and Henry 2003; Henry and Crawford 2005). The Cronbach’s alpha value for the present study was .90 for the DASS-21.

Alcohol Use

Participants’ alcohol consumption was assessed using the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al. 1993). The AUDIT questionnaire has been recommended by the World Health Organization as a brief screening tool for disordered alcohol consumptions (Saunders et al. 1993). Example questions include “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?” and “How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion?” Participants were asked to choose one of several response options that best reflected their consumption patterns (e.g. monthly, weekly). Scores were summed and higher scores reflected greater levels of alcohol use. Strong psychometric properties have been documented in college and primary care settings (Barry and Fleming 1993; Fleming et al. 1991). In this sample, the Cronbach’s alpha value was .88.

Cannabis Use

Participants’ cannabis use was assessed with a single question. Participants were asked how often they had used cannabis during the past six months, using six response options (e.g., never; not used in the past 6 months; a few times; monthly; weekly; daily).

Statistical Analysis Plan

First, using SPSS Version 24 (IBM Corp 2016), descriptive statistics for demographic variables (e.g., age, SES, educational status) and main study variables (i.e., scales, subscale scores) were calculated to describe the sample. To ascertain the appropriate number of factors underlying associations among the coping items, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using Mplus software version 8.0 (Muthén and Muthén 1998-2012). Following recommendations outlined by Fabrigar et al. (1999), maximum likelihood (ML) extraction method and a Geomin (oblique) rotation were performed. Several global fit statistics (χ2 goodness-of-fit test, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA], comparative fit index [CFI], the standardized root mean square residual [RMSR]), as well as parallel analysis, modification indices (MI), and patterns of factor loadings (i.e., theoretical feasibility) were examined to determine the most defensible factor structure underlying the data. In parallel analysis, eigenvalues from the sample data are compared with eigenvalues generated by random data to assist in factor retention (Brown 2006). For the fit statistics, the following guidelines were used to evaluate which model fit the data best: χ2 goodness-of-fit test: p > .05 good; RMSEA: < .05 good; CFI: > .95 good; SRMR: < .08 good. Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values were also examined; for both criteria, lower values indicate a better fit. Finally, to examine the function of coping, bivariate correlations between the coping factors and outcomes of interest (e.g., DASS score, competence) were calculated in SPSS.

Results

Among the 425 participants who completed the study, less than 0.5% of data were missing at the item level; no participant had missing data for an entire scale or subscale. Based on tests of predictors of missingness, data were treated as missing at random.

Aim 1: Examine the Structure of Coping

In EFA, parallel analysis, goodness of fit statistics, modification indices, and patterns of loadings/cross loadings were all examined to determine how many factors should be retained. Patterns of loadings and cross-loadings of the Geomin oblique rotations suggested that two items did not load clearly onto any of the examined factors. As such, item 4 (“You went off to be by yourself [or to be alone]”) and item 17 (“You did something to distract yourself [e.g., exercise, listen to music]”) were dropped from the analysis because they exhibited a loading of <.30 across all factors (Child 2006; Schmitt 2011). Item 4 had been selected to reflect the coping family isolation and may have had poor factor loadings because, unlike other items used for that coping family (e.g., item 22: “You tried to hide it”), it described social withdrawal rather than concealment. Item 17 had been included as an item for the coping family accommodation and, unlike several other items for that coping family (e.g., item 23: “You tried to notice or think about the good things in your life”), item 17 described a behavior rather than a cognitive process. As such, the poor factor loadings of items 4 and 17 could be explained by their content, which appeared to differ from the content of the other items included for the given coping family.

In parallel analysis (PA), eigenvalues from completely random data are generated and then compared to eigenvalues generated by the observed data (Brown 2006; Matsunaga 2010). PA has been shown to be a powerful tool to determine the number of factors underlying data (Fabrigar et al. 1999; Henson and Roberts 2006). A comparison of eigenvalues from the sample correlation matrix with eigenvalues from the PA (95th percentile), suggested that a 4-factor model fit the data best (see Table 2).

Next, fit statistics for the 4-, 5-, 6-, and 7-factor models were examined (Table 2).Footnote 2 The χ2 statistic “indicates the degree of discrepancy between the data’s variance/covariance pattern and that of the model being tested” (Matsunaga 2010, p. 106). Of note, the χ2 test statistic is dependent on the sample size such that the χ2 value increases with an increasing sample size (Russell 2002; Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003). Consequently, plausible models may be rejected based on significant χ2 statistics (Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003). Due to the large sample size used in the present study, the χ2 statistic was examined cautiously. Not surprisingly, the model χ2 statistics for the 4-, 5-, 6-, and 7-factor models were all statistically significant (Table 2). For the RMSEA criteria, the 7-factor model was the only model with a value of <.05. Similarly, for the CFI, the 7-factor model was the only model that obtained a value >.95. The 4-, 5-, 6-, and 7-factor models all had a value of <.08 for the SRMR, indicating potentially good model fit. The 7-factor model received the lowest value for the AIC; the 6-factor model received the lowest value for the BIC.

Modification Indices (MI) “provide an estimate in the change in the χ2 value that results from relaxing model restriction by freeing parameters that were fixed in the initial specification” (Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003, p. 55). Although a cutoff value of >10.0 is commonly used (Muthén and Muthén, 2010), a larger value of >20.0 was chosen for inspection in the present study due to the large sample size and the complexity of the tested models. Using this arbitrary cutoff of >20.0 for MI, the 5-factor model included five values that were greater than 20.0, the 6-factor model included three values that were greater than 20.0, and the 7-factor model included no values that were greater than 20.0. Given that the 4- and 5-factor models were inferior to the 6- and 7-factor models based on these fit statistics, the 4- and 5-factor models were no longer considered as candidate models in subsequent EFA analyses.

As a final step, loadings and cross-loadings of the Geomin oblique rotations for the 6-factor and 7-factor models were assessed for magnitude of loadings. This examination yielded support for a 7-factor model because most items loaded significantly with an absolute value of greater than >.30 onto a single factor (see Table 3). To assess the robustness of the model, the 7-factor model was re-run in Mplus using a different oblique rotation method, Promax. The loading patterns obtained through Promax also yielded support for the 7-factor model.

Taken together, a 7-factor model was judged to best fit the data. Specifically, the overall goodness of fit statistics indicated good model fit for a 7-factor model, χ2 (164) = 290.18, p < .00, RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI = 0.03–0.05), SRMR = .02, CFI = 0.97, AIC = 26,724, BIC = 27,587. Table 1 includes information on how each item from the original six coping families loaded onto the final 7-factor model that emerged in this EFA. In this model, items 3, 9, 15, 21, and 25 loaded onto factor 1, which was labelled Support-Seeking based on the item content. Items 1, 7, 13, and 19 loaded most clearly onto factor 2, which was labelled Problem-Solving. These two factors aligned with the coping families of support-seeking and problem-solving, as outlined by Skinner et al. (2003). Two items (11, 23) loaded most clearly onto factor 3 and were labelled as Cognitive Restructuring based on their item content. Factor 4 consisted of items 12 and 18 and was labelled Rumination based on the item content. Items 16 and 22 loaded onto the 5th factor, which was labelled Concealment and items 14 and 20 loaded most clearly onto the 6th factor, which was labelled as Wishful Thinking. Factor 7 included items 5, 6, 8, 24, and 26 and was labelled Avoidance. Whereas item 24 (“You did nothing”) had not loaded clearly (i.e., with an absolute value of >.30) onto any of the factors using Geomin rotation, it did load clearly onto the 7th factor using Promax rotation. Item 24 was included in the Avoidance factor because the inclusion of this item increased the Cronbach’s alpha from .68 to .74. Further, the content of item 24 aligned conceptually with the other items in that factor.Footnote 3

The Cronbach’s alpha values for the seven coping factorsFootnote 4 were as follows: .84 for Support-seeking, .79 for Problem-Solving, and .74 for Avoidance. Bivariate correlations for two-item factors were .69 for Rumination, .68 for Concealment, .60 for Cognitive Restructuring, and .60 for Wishful Thinking. Table 4 includes zero-order correlations between the seven coping factors and basic demographic information.

Aim 2: Examine the Function of Coping

Bivariate correlations between the seven coping factors and indicators of adaptation (e.g., Well-being, Harter Parent, Harter Romantic, Harter Social) and maladaptation (e.g., cannabis use, AUDIT score, DASS score) generally fell in the expected direction (Table 5). The three coping factors that have previously been associated with adaptive functioning—Support-Seeking, Problem-Solving, and Cognitive Restructuring—were significantly and positively associated with psychological well-being and social competence (Harter Parent, Harter Romantic, Harter Social). Similarly, all four coping behaviors that had previously been associated with maladaptation—Avoidance, Rumination, Concealment, and Wishful Thinking—were significantly and positively associated with the DASS score. Surprisingly, none of the seven coping factors were significantly correlated with cannabis use.

Discussion

Coping behaviors occur on a daily basis and can serve as a buffer against stress (e.g., Compas and Reeslund 2009; Curtis and Cicchetti 2007). Despite the importance of coping in human functioning, researchers have often disagreed on how to define and study this construct. As such, our understanding of the normative development of coping is somewhat limited (Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016). This study sought to examine the factor structure of coping in emerging adults to determine whether there is support for the six coping families (Aim 1). A second aim was to examine associations between coping behaviors and emerging adult outcomes (Aim 2).

Results from EFA yielded partial support for the six included coping families, as described by Skinner et al. (2003). Specifically, goodness of fit statistics, modification indices, and patterns of loadings and cross-loadings supported a 7-factor model of coping in this sample of emerging adults. Examination of the seven coping factors suggested some overlap between the seven coping factors from this study and the original coping families (Skinner et al. 2003). Most notably, Problem-Solving and Support-Seeking were two coping families that had been described by Skinner et al. (2003) and that also emerged as robust factors in this examination. It is important to consider that the robustness of these two coping factors could, at least partially, be explained by the nature of these two coping behaviors: both describe relatively specific and narrow behaviors that may be more readily assessed than some other coping behaviors.

Although there was some overlap between the six original coping families and the seven coping factors from this study, there were also some notable differences. For example, in this study, the two items “you reminded yourself that things were going pretty well for you overall” (item 11) and “you tried to notice or think about the good things in your life” (item 23) loaded onto the factor Cognitive Restructuring. In the original coping family conceptualization, these two questions had been included within the coping family accommodation—a coping family that also included other behaviors, such as distraction and acceptance. The existence of the narrow Cognitive Restructuring factor in this emerging adult sample supports the view that important cognitive growth (e.g., abstract reasoning, planning, attention) occurs during late adolescence and the early twenties (e.g., Caballero et al. 2016; Craik and Bialystok 2006; Yurgelun-Todd 2007). Stated differently, unlike younger samples, emerging adults may have a greater ability to use cognitive coping strategies based on important brain maturation processes that occur during this age. Such developmental processes may, at least partially, help explain why EFA results from this study yielded support for a Cognitive Restructuring factor.

Similarly, this study also found support for a Rumination coping factor, consisting of the two items “you kept thinking about it over and over” (item 12) and “you could not get it out of your head” (item 18). The existence of the Rumination coping factor also represents a point of divergence from the original coping family conceptualization. In the original coping family framework, these two items had been included within the broader coping family submission. The emergence of a distinct Rumination factor in this study supports the view that ruminative processes may be occurring with greater frequency during emerging adulthood than during other developmental periods (Nolen-Hoeksema and Aldao 2011). In fact, prior research suggests that, across adolescence, ruminative thinking becomes more stable (or trait-like) and also that rumination as a coping strategy increases (Hampel and Petermann 2005; Rood et al. 2009). Given that rumination has consistently been liked to depression in adolescent and adult samples (Garnefski et al. 2003; Nolen-Hoeksema 2000), the salience of the Rumination factor amongst emerging adults has relevance for applied work.

The coping factor Avoidance (i.e., items 5, 6, 8, 24, 26) supported by EFA analyses in this study also represents a deviation from the original coping family framework. In fact, the Avoidance factor that emerged in this study consisted of items from three different coping families, as described by Skinner et al. (2003): accommodation, submission, and escape. For example, item 5 (“You tried to just accept the situation”) had initially been conceptualized as an adaptive coping behavior and had been included within the original coping family accommodation. As such, it was initially surprising that item 5 loaded onto the Avoidance factor in this study. However, a potential explanation for this unexpected finding is that the wording of this item—trying to accept the situation—implied that the attempt to accept the situation was not actually successful. Taken together, the coping factor Avoidance that was found in this study did not support the original coping family framework.

Bivariate correlations yielded information on the function of the seven coping factors identified in this EFA. Three coping behaviors previously associated with adaptive functioning—Support-Seeking, Problem-Solving, and Cognitive Restructuring—were all significantly and positively associated with four indicators of adaptive functioning. More specifically, these three coping behaviors were associated with psychological well-being as well as social competence (i.e., self-reported relationships with parents, romantic partners, and friends). The finding that certain coping behaviors are correlated with social competence are particularly pertinent to the developmental period of emerging adulthood. As described by Arnett (2000), one of the developmental tasks of 18–29 year-olds is to navigate relationships with parents and learn to form and maintain romantic relationships.

Similarly, coping behaviors previously associated with maladaptation, such as Avoidance and Wishful Thinking, were significantly and positively associated with alcohol use and psychological distress. The associations that were found in this study generally align with prior work. For example, support-seeking, problem- solving, and accommodation have been linked in prior research to positive developmental outcomes (Skinner et al. 2013; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016). In contrast, empirical evidence suggests that other coping responses, such as escape, submission, and opposition, are often linked to maladaptation (Skinner et al. 2013; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016).

Implications

Results from this study have implications for basic research and applied work. With regard to basic research, it is important to understand whether and how coping behaviors develop across emerging adulthood. Results from this study support the view that coping during emerging adulthood is continuous from prior developmental stages in some respects; emerging adults in this sample appeared to use Support-Seeking and Problem-Solving—two coping behaviors that are commonly used by children and adolescents (Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011). However, there also appears to be some discontinuity in coping; new coping factors, such as Cognitive Restructuring and Rumination were found amongst this sample.

This study also has implications for applied work. Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck et al. (2016) recently called for the need to identify ‘good news’ and ‘bad news’ coping for different developmental periods in an effort to foster healthy development (p. 42). Identifying coping strategies that are most commonly used by emerging adults and that are associated with adaptation and negative outcomes, respectively, can inform prevention and intervention efforts. Given that most prior work has focused on negative developmental outcomes, it is particularly important to identify stress responses that are associated with adaptation (Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2016). Bivariate correlations suggested that the two coping factors Problem-Solving and Cognitive Restructuring were both associated with adaptive outcomes and may represent adaptive ways to cope with interpersonal stress during emerging adulthood.

In an effort to support adaptive development, applied work could explicitly target and strengthen problem-solving and cognitive restructuring in emerging adults. These results directly align with general principles of evidence-based treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; e.g., Beck 2011; Beck et al. 1979). CBT targets maladaptive thinking patterns in an effort to reduce psychological distress and clinical symptoms (e.g., Beck 2011; Beck et al. 1979). Many evidence-based CBT interventions for youth and adults (e.g., Treating Anxious Children and Adolescents, Rapee et al. 2000; Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders, Barlow et al. 2017) teach cognitive restructuring through concepts. Similarly, various evidence-based clinical interventions for children and adolescents include modules to teach/strengthen problem-solving skills. Specifically, basic problem-solving interventions teach individuals to 1) identify the problem, 2) generate a list of possible solutions, 3) evaluate options, and 4) implement the best solution (see Friedberg and McClure 2015). Given that CBT can be delivered effectively in individual and group settings (e.g., Chen et al. 2003; Manassis et al. 2002), cognitive restructuring and problem-solving could be taught and practiced in individual and group psychotherapy settings.

Findings from this study also inform prevention efforts. Recent research suggests that brief prevention workshops present an effective way to teach emerging adults useful emotion management skills. Bentley et al. (2018) demonstrated that that a single-session preventative intervention that teaches at-risk college students adaptive emotion management skills can result in small, but statistically significant, reductions in neuroticism and experiential avoidance. Such findings suggest that young adults who are at risk for developing anxiety and depressive symptoms may benefit from completing a single-session workshop that teaches adaptive emotion management (Bentley et al. 2018). Results from this study tentatively suggest that modules on problem-solving and cognitive-restructuring could be helpful to emerging adults. Given that preventative web-based approaches for college students also appear to be acceptable and effective (Eustis et al. 2018), prevention efforts could also be delivered online to ensure that a wide range of emerging adults, including those not currently enrolled at postsecondary institutions, can benefit from such prevention efforts.

Strengths and Limitations

This study included several strengths. Unlike many prior studies, which recruited small and/or demographically non-representative samples of college students, this study was based on a large and demographically representative sample of emerging adults. These sample characteristics allowed for the use of powerful statistical tools, such as EFA, and allowed for greater generalizability of study results. Further, this study considered a range of emerging adult outcomes, including those related to adaptive functioning. This represents a strength given that many prior examinations on coping in emerging adults had focused primarily on maladaptive outcomes.

This study also included several limitations. First, data collection was cross-sectional; results therefore do not support causal inferences (e.g., the view that coping behaviors predicted emerging adult functioning). Second, all variables were assessed using self-report questionnaires. Although self-report measures can provide meaningful insight into an individual’s cognitive processes, self-report can be inaccurate (e.g., difficulty recalling information, reluctance to report maladaptive coping responses; Compas et al. 2001). Multi-informant assessments provide advantages for assessment of children and adults (Achenbach et al. 2005; Kraemer et al. 2003); however, it was not feasible to corroborate emerging adults’ self-report with parent, peer, or other objective ratings (e.g., achievement test scores) in the present study. A third limitation pertains to the particular eligibility criteria used in this study, such as the requirement that participants have a 90% prior HIT approval. It is possible that this MTurk criterion led to the recruitment of a sample that was somewhat more conscientious, attentive, and rule-abiding as compared to a population sample.

Finally, the measurement of the main variable of interest, coping, also included some shortcomings. Although initial studies by Skinner and colleagues identified 12 coping families, the present study only assessed six coping families. The focus on these six coping families was deemed warranted on the basis of their prevalent use and their relevance to the emerging adulthood developmental period. Further, the coping questionnaire asked participants to report how they cope with interpersonal problems. Although emerging adults commonly experience social stress (e.g., Aldridge-Gerry et al. 2011), thereby justifying the focus on this type of stress, results from this study may therefore be limited to coping with this specific type of stress. Further, the coping measure neither asked participants to identify which interpersonal stressor they were thinking of when completing the coping questions, nor assessed how participant perceived this stressor (e.g., intensity of stress, perceived controllability of stress, familiarity with stress).

These limitations notwithstanding, results from this study expand what is known about coping in emerging adult. This age group may be managing stress in a way that is somewhat specific to their developmental stage (e.g., relying more heavily on cognitive restructuring). It may therefore be beneficial to assess such coping behaviors in emerging adult samples. To gain a more complete picture of coping in emerging adults, future studies should consider longitudinal data collection, multi-informant assessment, consideration of all 12 coping families, and nuanced assessment of particular stressors.

Notes

Despite creating an age limit of 30 years in MTurk, one participant reported an age of 31 years and was retained in this sample.

Fit Statistics for the 2- and 3-factor models are not presented here because they indicated poorer fit relative to 4-, 5-, 6-, and 7-factor models.

The seven coping factors identified in this EFA will hereafter be referred to as Support-Seeking, Problem-Solving, Cognitive Restructuring, Rumination, Concealment, Wishful Thinking, and Avoidance to distinguish them from related constructs.

Cronbach’s alpha values are only reported for the three factors that consisted of three or more items; bivariate correlations are reported for factors that consisted of two items.

References

Achenbach, T. M., Krukowski, R. A., Dumenci, L., & Ivanova, M. Y. (2005). Assessment of adult psychopathology: Meta-analyses and implications of cross-informant correlations. Psychological Bulletin, 131(3), 361–382.

Aldridge-Gerry, A. A., Roesch, S. C., Villodas, F., McCabe, C., Leung, Q. K., & Da Costa, M. (2011). Daily stress and alcohol consumption: Modeling between-person and within-person ethnic variation in coping behavior. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(1), 125–134.

American College Health Association. (2006). American college health association national college health assessment (ACHA-NCHA) spring 2005 through reference group data report. Journal of American College Health, 55, 5–16.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480.

Arnett, J. J. (2006). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J., Žukauskienė, R., & Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576.

Asberg, K. K., Bowers, C., Renk, K., & McKinney, C. (2008). A structural equation modeling approach to the study of stress and psychological adjustment in emerging adults. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 39(4), 481–501.

Ayers, T. S., Sandler, I. N., West, S. G., & Roosa, M. W. (1996). A dispositional and situational assessment of children’s coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality, 64, 923–958.

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Sauer-Zavala, S., Latin, H. M., Ellard, K. K., Bullis, J. R., et al. (2017). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Barry, K. L., & Fleming, M. F. (1993). The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) and the SMAST-13: Predictive validity in a rural primary care sample. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 28(1), 33–42.

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. New York: Guilford.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford.

Bentley, K. H., Boettcher, H., Bullis, J. R., Carl, J. R., Conklin, L. R., Sauer-Zavala, S., Pierre-Louis, C., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2018). Development of a single-session, transdiagnostic preventive intervention for young adults at risk for emotional disorders. Behavior Modification, 42(5), 781–805.

Blount, R. L., Simons, L. E., Devine, K. A., Jaaniste, T., Cohen, L. L., Chambers, C. T., & Hayutin, L. G. (2008). Evidence-based assessment of coping and stress in pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(9), 1021–1045.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s mechanical Turk a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5.

Caballero, A., Granberg, R., & Tseng, K. Y. (2016). Mechanisms contributing to prefrontal cortex maturation during adolescence. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 4–12.

Casler, K., Bickel, L., & Hackett, E. (2013). Separate but equal? A comparison of participants and data gathered via Amazon’s MTurk, social media, and face-to- face behavioral testing. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2156–2160.

Chandler, J., & Shapiro, D. (2016). Conducting clinical research using crowdsourced convenience samples. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 53–81.

Chandler, J., Mueller, P., & Paolacci, G. (2014). Nonnaïveté among Amazon mechanical Turk workers: Consequences and solutions for behavioral researchers. Behavior Research Methods, 46(1), 112–130.

Chen, E., Touyz, S. W., Beumont, P. J., Fairburn, C. G., Griffiths, R., Butow, P., et al. (2003). Comparison of group and individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 33(3), 241–254.

Child, D. (2006). The essentials of factor analysis (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Continuum.

Clarke, A. T. (2006). Coping with interpersonal stress and psychosocial health among children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(1), 10–23.

Coccia, C., & Darling, C. A. (2016). Having the time of their life: College student stress, dating and satisfaction with life. Stress and Health, 32(1), 28–35.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Coiro, M. J., Bettis, A. H., & Compas, B. E. (2017). College students coping with interpersonal stress: Examining a control-based model of coping. Journal of American College Health, 65(3), 177–186.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87.

Compas, B. E., & Reeslund, K. L. (2009). Processes of risk and resilience: Linking contexts and individuals. R. Lerner, & L. Steinberg. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 2, 271–272.

Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Dunbar, J. P., Watson, K. H., Bettis, A. H., Gruhn, M. A., & Williams, E. K. (2014). Coping and emotion regulation from childhood to early adulthood: Points of convergence and divergence. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(2), 71–81.

Craik, F. I., & Bialystok, E. (2006). Cognition through the lifespan: Mechanisms of change. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(3), 131–138.

Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2003). The depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) Normative data and latent structure in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 111–131.

Curtis, W. J., & Cicchetti, D. (2007). Emotion and resilience: A multilevel investigation of hemispheric electroencephalogram asymmetry and emotion regulation in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Development and Psychopathology, 19(3), 811–840.

Dusselier, L., Dunn, B., Wang, Y., Shelley, M. C., & Whalen, D. F. (2005). Personal, health, academic, and environmental predictors of stress for residence hall students. Journal of American College Health, 54(1), 15–24.

Eisenberg, D., Gollust, S. E., Golberstein, E., & Hefner, J. L. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(4), 534–542.

Eustis, E. H., Hayes-Skelton, S. A., Orsillo, S. M., & Roemer, L. (2018). Surviving and thriving during stress: A randomized clinical trial comparing a brief web-based therapist-assisted acceptance-based behavioral intervention versus waitlist control for college students. Behavior Therapy, 49(6), 889–903.

Eysenbach, G. (2004). Improving the quality of web surveys: The checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). Journal of Medical Internet Research, 6(3), e34.

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299.

Feenstra, J. S., Banyard, V. L., Rines, E. N., & Hopkins, K. R. (2001). First-year students’ adaptation to college: The role of family variables and individual coping. Journal of College Student Development, 42(2), 106–113.

Fleming, M. F., Barry, K. L., & Macdonald, R. (1991). The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in a college sample. International Journal of the Addictions, 26(11), 1173–1185.

Friedberg, R. D., & McClure, J. M. (2015). Clinical practice of cognitive therapy with children and adolescents: The nuts and bolts (Second ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Burton, C. L., & Bonanno, G. A. (2012). Coping flexibility, potentially traumatic life events, and resilience: A prospective study of college student adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 31(6), 542–567.

Garnefski, N., Boon, S., & Kraaij, V. (2003). Relationships between cognitive strategies of adolescents and depressive symptomatology across different types of life event. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(6), 401–408.

Hampel, P., & Petermann, F. (2005). Age and gender effects on coping in children and adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(2), 73–83.

Harter, S. (2012). Manual for the self-perception profile for college students. Denver, CO: University of Denver.

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227–239.

Henson, R. K., & Roberts, J. K. (2006). Use of exploratory factor analysis in published research: Common errors and some comment on improved practice. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 393–416.

IBM Corp. Released. (2016). IBM SPSS statistics for mac, version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Jaser, S. S., & White, L. E. (2011). Coping and resilience in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37(3), 335–342.

Kessler, R. C., & Wang, P. S. (2008). The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 115–129.

Kessler, R. C., Birnbaum, H., Demler, O., Falloon, I. R., Gagnon, E., Guyer, M., et al. (2005). The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Biological Psychiatry, 58(8), 668–676.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222.

Keyes, C. L. M., Wissing, M., Potgieter, J. P., Temane, M., Kruger, A., & van Rooy, S. (2008). Evaluation of the mental health continuum–short form (MHC–SF) in Setswana-speaking south Africans. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 15(3), 181–192.

Kraemer, H. C., Measelle, J. R., Ablow, J. C., Essex, M. J., Boyce, W. T., & Kupfer, D. J. (2003). A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: Mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(9), 1566–1577.

Kung, F. Y., Kwok, N., & Brown, D. J. (2018). Are attention check questions a threat to scale validity? Applied Psychology, 67(2), 264–283.

Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. New York: Springer.

Lee, C., Dickson, D. A., Conley, C. S., & Holmbeck, G. N. (2014). A closer look at self-esteem, perceived social support, and coping strategy: A prospective study of depressive symptomatology across the transition to college. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33(6), 560–585.

Lovidbond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behavior Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343.

Manassis, K., Mendlowitz, S. L., Scapillato, D., Avery, D., Fiksenbaum, L., Freire, M., et al. (2002). Group and individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety disorders: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(12), 1423–1430.

Matsunaga, M. (2010). How to factor-analyze your data right: Do’s, don’ts, and how-to’s. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 97–110.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2010). Mplus 6.0. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus User’s Guide (Seventh ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 504–511.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Aldao, A. (2011). Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(6), 704–708.

Park, C. L., Armeli, S., & Tennen, H. (2004). The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65(1), 126–135.

Peisch, V. (2019). Towards a developmental theory of coping: The structure and function of coping in emerging adults (unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Vermont, Burlington, VT.

Pierceall, E. A., & Keim, M. C. (2007). Stress and coping strategies among community college students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 31(9), 703–712.

Rapee, R. M., Wignall, A., Hudson, J. L., & Schniering, C. A. (2000). Treating anxious children and adolescents: An evidence-based approach. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Rood, L., Roelofs, J., Bögels, S. M., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schouten, E. (2009). The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(7), 607–616.

Russell, D. W. (2002). In search of underlying dimensions: The use (and abuse) of factor analysis in personality and social psychology bulletin. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1629–1646.

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23–74.

Schmitt, T. A. (2011). Current methodological considerations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29, 304–321.

Shapiro, D. N., Chandler, J., & Mueller, P. A. (2013). Using mechanical Turk to study clinical populations. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(2), 1–8.

Skinner, E. A., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2016). The development of coping: Stress, neurophysiology, social relationships, and resilience during childhood and adolescence. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216–269.

Skinner, E., Pitzer, J., & Steele, J. (2013). Coping as part of motivational resilience in school: A multidimensional measure of families, allocations, and profiles of academic coping. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(5), 803–835.

Thompson, R. J., Mata, J., Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Jonides, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2010). Maladaptive coping, adaptive coping, and depressive symptoms: Variations across age and depressive state. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(6), 459–466.

Todd, M., Tennen, H., Carney, M. A., Armeli, S., & Affleck, G. (2004). Do we know how we cope? Relating daily coping reports to global and time-limited retrospective assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 310–319.

Wichstrom, L. (1995). Harter’s self-perception profile for adolescents: Reliability, validity, and evaluation of the question format. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65(1), 100–116.

Yurgelun-Todd, D. (2007). Emotional and cognitive changes during adolescence. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 17(2), 251–257.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Skinner, E. A. (2008). Adolescents coping with stress: Development and diversity. Prevention Researcher, 15(4), 3–7.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Skinner, E. A. (2011). The development of coping across childhood and adolescence: An integrative review and critique of research. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(1), 1–17.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Lees, D. C., Bradley, G. L., & Skinner, E. A. (2009). Use of an analogue method to examine children’s appraisals of threat and emotion in response to stressful events. Motivation and Emotion, 33(2), 136–149.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Skinner, E. A., Morris, H., & Thomas, R. (2013). Anticipated coping with interpersonal stressors: Links with the emotional reactions of sadness, anger, and fear. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(5), 684–709.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Dunbar, M. D., Ferguson, S., Rowe, S. L., Webb, H., & Skinner, E. A. (2014). Guest editorial: Introduction to the special issue. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 65–70.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Van Petegem, S., & Skinner, E. A. (2016). Emotion, controllability and orientation towards stress as correlates of children’s coping with interpersonal stress. Motivation and Emotion, 40(1), 178–191.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Vermont. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This manuscript is based on the first author’s doctoral dissertation (Peisch 2019).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peisch, V., Burt, K.B. The structure and function of coping in emerging adults. Curr Psychol 41, 4802–4814 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00990-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00990-z