Abstract

A substantial body of evidence indicates that mindfulness is associated with less anxiety. However, less is known about the mechanisms by which mindfulness decreases anxiety. One possibility is that mindfulness encourages individuals to be less experientially avoidant (e.g., less likely to attempt to suppress or avoid unwanted private experiences), a hallmark of anxiety. The purpose of the present research was to assess whether less experiential avoidance accounted for the inverse relation between mindfulness and anxiety. Two studies were conducted with college students (Ns = 493 and 320, respectively). Participants completed self-report measures of trait mindfulness, anxiety, and experiential avoidance online (Study 1) and in person (Study 2) for course credit. Across both studies, greater mindfulness was associated with lower experiential avoidance and anxiety, and experiential avoidance was positively associated with anxiety. Furthermore, experiential avoidance significantly accounted for the relation between mindfulness and anxiety in both studies. Alternative mediation models were also tested. These findings suggest that mindfulness may improve anxiety through its effects on experiential avoidance. Given that experiential avoidance is thought to be involved in the development and maintenance of several psychological disorders, interventions involving mindfulness training may have promising broad mental health benefits. However, further research is needed to replicate these findings across clinical populations and therapeutic settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mindfulness represents the ability to non-judgmentally attend to the present moment and accept experiences (Bishop et al. 2004; Kabat-Zinn 2003). Over the last two decades, a considerable amount of research has explored the potential mental health benefits of mindfulness (Baer 2003). Several interventions exist that utilize mindfulness practices (e.g., meditation, yoga) and have been shown to reduce pathological behavior and to lessen overall distress across an array of psychological disorders (e.g., Bach and Hayes 2002; Linehan et al. 1999; Lynch et al. 2003). In particular, evidence suggests that mindfulness is useful in the treatment of anxiety (cf. Hofmann et al. 2010). Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions, such as Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy and Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction, in the reduction of anxiety (e.g., Craigie et al. 2008; Evans et al. 2008; Kabat-Zinn et al. 1992).

In addition to a skill that can be increased through practice (Baer et al. 2008; Falkenstrom 2010; Goodall et al. 2012), mindfulness also represents a dispositional trait. Differing levels of mindfulness have been noted in individuals with no prior mindfulness training (Baer et al. 2006; Goodall et al. 2012). However, mindfulness-based interventions and trait mindfulness are related, such that repeated practice increases one’s ability and propensity over time to be mindful on a regular basis (i.e., trait mindfulness; Garland et al. 2010; Kiken et al. 2015; Quaglia et al. 2016).

Similar to the intervention research, a substantial body of literature suggests that trait mindfulness is associated with better mental health, especially lower levels of anxiety (e.g., Brown and Ryan 2003; Hou et al. 2014; Mayer et al. 2019; Pepping et al. 2016; Tomlison et al., 2018). Thus, consistent evidence supports an inverse relation between mindfulness and anxiety. Potentially, mindfulness practice may reduce psychological distress, and trait mindfulness may be a protective factor against psychological distress. But, the mechanisms by which mindfulness affects anxiety are not clear.

Anxiety is an emotion characterized by worried thoughts, feelings of tension, and physiological responses, such as increased blood pressure (American Psychological Association 2015). Anxious individuals are often preoccupied with the possibility that an unwanted event will occur in the future (Carleton et al. 2014; Fetzner et al., 2013; Holaway et al., 2006) and often engage in experiential avoidance, or persistent attempts to control their experiences (e.g., thoughts, emotions, memories, bodily sensations, or behavioral tendencies) and to avoid the anxiety-provoking stimulus (Forsyth et al. 2006; Hayes et al. 2004; Kashdan et al. 2008). Although experiential avoidance may initially have seemingly positive effects, such as a reduction of the avoided discomfort, this benefit is short lived. A growing body of research has shown that following experiential avoidance, unwanted thoughts will often return with greater intensity and frequency (Gold and Wegner 1995; Wegner et al. 1987), and that individuals who attempt to avoid unwanted private experiences tend to feel higher levels of anxiety (Borkovec et al. 2004; Briggs and Price 2009; Hayes et al. 1996; Newman and Llera 2011; Szentagotait 2006; Tull et al. 2004). Additionally, experiential avoidance may play a substantial role in the development and maintenance of psychological distress, more so than the actual experiences that the individual is attempting to avoid (Sloan 2004; Vowles et al. 2014).

Mindfulness may be particularly effective in reducing anxiety because it diminishes these avoidance processes. Because experiential avoidance occurs when an individual is unwilling to remain in contact with the possibility of an unwanted experience in the present moment, experiential avoidance can be conceptualized as the antithesis of mindfulness. That is, individuals who are higher in experiential avoidance attempt to intentionally avoid the present moment by engaging in deliberate efforts to control or escape from unwanted cognitions or emotions. Thus, mindfulness may reduce anxiety, by affecting experiential avoidance.

To date, a few studies have found trait mindfulness to be inversely related to experiential avoidance (Boni et al. 2018; Brem et al. 2017; Kroska et al. 2018; Mahoney et al. 2015; Raines et al. 2018). Further, Raines et al. (2018) found that trait mindfulness moderated the relation between experiential avoidance and anxiety. Specifically, in a sample of Latinos in a federally qualified health center, experiential avoidance was positively associated with anxiety for individuals with low, but not high, levels of trait mindfulness. Experiential avoidance and trait mindfulness have also been considered parallel mediators of the relation between established predictors of anxiety and the expression or development of anxiety-related symptoms. For example, both trait mindfulness and experiential avoidance significantly mediated the relation between childhood trauma and the development of OCD symptoms (Kroska et al. 2018), as well as the relation between length of yoga practice and anxiety symptoms (Boni et al. 2018).

However, rather than being independent predictors of anxiety, mindfulness may influence experiential avoidance. Indeed, a mindfulness intervention reduced both experiential avoidance and anxiety (Antoine et al. 2018), suggesting that mindfulness may actually exert an effect on experiential avoidance. In a sample of men in a residential substance abuse treatment facility, greater trait mindfulness was related to less compulsive sexual behavior indirectly through less experiential avoidance (Brem et al. 2017). Thus, initial evidence suggests that experiential avoidance may, in fact, account for the relation between mindfulness and anxiety.

The goal of the current research was to test the indirect effect of trait mindfulness on anxiety through experiential avoidance. Relatively little research has examined the relation between mindfulness and experiential avoidance, but theoretically, mindfulness should inherently lessen experiential avoidance. Previous research suggests that mindfulness is inversely associated with experiential avoidance (Boni et al. 2018; Brem et al. 2017; Kroska et al. 2018; Mahoney et al. 2015; Raines et al. 2018). Thus, experiential avoidance may be an important mechanism to understanding how mindfulness reduces anxiety. Two correlational studies were conducted with large, non-clinical university student samples. We hypothesized that trait mindfulness would be inversely associated with both experiential avoidance and anxiety. As previously demonstrated, anxiety and experiential avoidance were expected to be positively correlated. Furthermore, experiential avoidance was hypothesized to significantly account for the relation between trait mindfulness and anxiety.

Study 1

Participants

Participants were 493 undergraduate students at a large southern university, who received course credit for their participation. The university’s institutional review board approved the study. Seven participants were removed from the study for providing inconsistent answers on more than three scales (e.g., giving the same response to all items). The final sample consisted of 486 participants (72.9% female; Mage = 20.04 years, SD = 8.63). The race/ethnicity of the sample was: Caucasian (75.30%), African American (18.51%), Hispanic or Latino (2.05%), Asian (1.02%), and Other (3.08%).

Procedure

Participants registered for the study online. After providing online consent, participants then completed an online survey which consisted of the following questionnaires presented in random order, except for the demographics which appeared last.

Measures

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown and Ryan 2003; α = .82)

The MAAS is a 15-item self-report measure of trait mindfulness. The MAAS has demonstrated convergent validity with other measures of mindfulness (e.g., Mindfulness/Mindlessness Scale; Brown and Ryan 2003). Participants indicate the extent to which they experience each item (e.g., “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present”) on a scale from 1 (“almost always”) to 6 (“almost never”). As recommended by Brown and Ryan (2003), a composite score was created by averaging the 15 items. Higher scores reflect higher mindfulness.

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II; Bond et al. 2011; α = .84)

The AAQ-II is a 7-item scale that measures experiential avoidance and has shown high test re-test reliability 3 and 12 months later (.81 and .79, respectively; Bond et al. 2011). Individuals rate each item (e.g., “I worry about not being able to control my worries and feelings.”) on a scale from 1 (“never true”) to 7 (“always true”). A composite score was created by averaging the 7 items, as recommended by Bond et al. (2011), such that higher scores represent greater experiential avoidance.

Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire (MEAQ; Gamez et al. 2011; α = .91–.92)

The MEAQ is a 62-item self-report questionnaire that measures the different dimensions of experiential avoidance: Behavioral Avoidance, Distress Aversion, Procrastination, Distraction and Suppression, Repression and Denial, and Distress Endurance. Individuals rate each item (e.g., “I usually try to distract myself when I feel something painful”) on a scale from 1 (“strongly agree”) to 6 (“strongly disagree”). As recommended by Gamez et al. (2011), a composite score was created by reverse scoring necessary items and summing the scores for items within each dimension. Higher scores on each subscale indicate greater experiential avoidance on that dimension. A MEAQ total score was also created by taking a sum of the six subscales (Gamez et al. 2011). The subscales, as well as total score, have demonstrated high convergent validity with other measures of experiential avoidance (e.g., Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II) in student samples (Gamez et al. 2011).

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al. 1988; α = .92)

The BAI is a 21-item self-report inventory where individuals rate their experiences of anxiety related symptoms (e.g., terrified, hands trembling) on a scale from 0 (“not having a symptom at all”) to 3 (“being severely bothered by a symptom”). Per original scoring directions, a composite score was created by summing the 21 items, such that larger scores indicate more severe anxiety. The BAI has shown high test-retest reliability over 1 week (.75; Beck et al. 1988).

State Trait Anxiety Inventory-State Scale (STAI-S; Spielberger et al. 1970; α = .93)

The STAI-S is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses current anxiety symptoms. Individuals rate their experiences of anxiety related symptoms (e.g., “I am presently worrying over possible misfortunes”) on a scale from 1 (“not having a symptom at all”) to 4 (“very much experiencing a symptom”). The STAI-S was included to assess the cognitive and affective aspects of anxiety, which are not otherwise covered by the BAI. er original scoring directions, a composite score was created by summing the 20 items. Higher scores indicate greater state anxiety. The STAI has shown high test-retest reliability over 2 months (.69 to .89; Spielberger et al. 1970).

Demographics

Individuals were asked to provide information on gender, race, age, GPA, educational attainment, employment history, and household income on a demographic questionnaire. Additional questions were included to gather information regarding history of meditation practice, yoga, tai chi, or martial arts, because of the elements of mindfulness that exist within these practices.

Data Analyses

First, we examined skewness and kurtosis to ensure all variables were normally distributed. Second, to assess the associations between trait mindfulness, anxiety, and experiential avoidance, bivariate correlations were calculated. Third, we tested whether experiential avoidance accounted for the association between trait mindfulness and anxiety using 5000 bootstrapped samples with the PROCESS macro model 4 for SPSS (Preacher and Hayes 2004). Indirect effects were considered to be significant if the 95% confidence interval did not include zero (Preacher and Hayes 2004; Preacher et al. 2007). Beta coefficients reported are unstandardized, as recommended by Hayes (2013). Fourth, we tested an alternative model whereby trait mindfulness was tested as a mediator of the association between experiential avoidance and anxiety. These steps were taken in both Study 1 and Study 2.

Results

Means, standard deviations, and alphas for all Study 1 measures are presented in Table 1. Data met all assumptions for the planned analyses (e.g., normal distribution). To examine the simple associations among all of the variables, bivariate correlations were calculated (see Table 1). Trait mindfulness was inversely correlated with most measures of experiential avoidance. Individuals who were more mindful tended to have lower levels of experiential avoidance. However, trait mindfulness was not significantly associated with the Distraction and Suppression subscale of the MEAQ. That is, mindfulness was not related to the tendency to attempt to suppress thoughts and emotions. Mindfulness was negatively associated with anxiety, such that individuals with higher mindfulness scores tended to have lower anxiety scores.

Overall, both anxiety measures were positively associated with the experiential avoidance measures. Individuals who reported experiencing more anxiety also reported engaging in more experiential avoidance. Most of the experiential avoidance measures were positively correlated. However, the Distress Endurance subscale of the MEAQ was negatively associated with the Distraction and Suppression subscale of the MEAQ. Additionally, the Distress Endurance subscale was not significantly correlated with the Distress Aversion subscale, and the Distraction and Suppression subscale was not significantly correlated with the Repression Denial subscale. The AAQ-II was also not significantly correlated with the Distraction and Suppression subscale of the MEAQ.

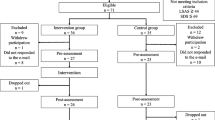

To investigate whether experiential avoidance accounted for the association between trait mindfulness and anxiety, a mediation analysis was conducted using 5000 bootstrapped samples with the PROCESS macro (Preacher and Hayes 2004). Trait mindfulness was entered as the predictor variable, experiential avoidance as the mediator, and anxiety as the criterion variable (see Fig. 1). Separate models were conducted with each individual experiential avoidance and anxiety measure (see Supplemental Table 1). The patterns of results were generally the same, except for a couple of analyses with the Behavioral Avoidance and Distraction and Suppression subscales of the MEAQ. For ease of interpretation, a single model is reported with composite variables for experiential avoidance and anxiety. The AAQ-II and each subscale of the MEAQ were standardized and then averaged to create a composite experiential avoidance variable (α = .90). Similarly, the BAI and STAI-S were each standardized and then averaged to create a composite anxiety variable (α = .95).

The overall model explained 30.56% of the variance in anxiety, F(2, 483) = 106.29, p < .001. There was a significant indirect effect of trait mindfulness on anxiety through experiential avoidance (b = −.16, 95% CI [−.22, −.11]). After including the significant indirect path, the direct effect (b = −.53, p < .001) between trait mindfulness and anxiety was reduced (b = −.37, p < .001), suggesting that the association between higher mindfulness and lower levels of anxiety was partially accounted for by less experiential avoidance.

Given that our data were correlational and cross-sectional, we tested an alternative model with mindfulness as a possible mediator of the relation between experiential avoidance and anxiety. Experiential avoidance was entered as the predictor variable, trait mindfulness as the mediator, and anxiety as the criterion variable (see Fig. 2). Again, composite variables for anxiety and experiential avoidance are reported for ease of reading. Models utilizing the individual measures were tested and the results were similar (see Supplemental Table 2). There was a significant indirect effect of experiential avoidance on anxiety through trait mindfulness (b = .19, 95% CI [.13, .26]). After including the significant indirect path, the direct effect (b = .71, p < .001) between experiential avoidance and anxiety was reduced (b = .52, p < .001), suggesting that the association between greater experiential avoidance and higher levels of anxiety was partially accounted for by lower trait mindfulness.

Discussion

These findings provide preliminary evidence that the relation between trait mindfulness and anxiety is in part due to lower experiential avoidance. Mindfulness was inversely related to experiential avoidance, which in turn was associated with self-reported anxiety. However, there was also support for an alternative model, in which trait mindfulness accounted for some of the relation between experiential avoidance and anxiety. Potentially, the relation between mindfulness and experiential avoidance is bi-directional.

Study 2

The purpose of Study 2 was to replicate and extend the findings from Study 1, using multiple measures of mindfulness. A limitation of Study 1 was the utilization of the MAAS, which is a unidimensional assessment of mindfulness. Generally, mindfulness is considered to be a multidimensional construct (Baer et al. 2006). As such, we included a multidimensional assessment of mindfulness in Study 2. To assess generalizability of the findings, a second sample, from a different university, was utilized. Also, Study 2 participants completed all measures in a laboratory setting, rather than online like Study 1 participants.

Method

Participants

Participants were 320 undergraduate students at a large mid-Atlantic university, who received course credit for their participation. The university’s institutional review board approved the study. Six participants were removed from analyses because they were either univariate or multivariate outliers, and 11 participants were removed from analyses because they provided inconsistent responses across three or more scales, leaving a final sample of 303. Participants were 69.6% female, with a mean age of 20.09 years (SD = 6.20). The race/ethnicity of the sample was Caucasian (81.5%), African American (9.57%), Hispanic or Latino (2.64%), Asian (3.63%), and other (2.64%).

Procedure

Participants were recruited for an in-person study via the Department of Psychology’s subject pool. Sessions were conducted in a psychology laboratory and were run in groups of, at most, nine participants. Upon arrival to the lab, participants were seated in individual cubicles and provided informed consent. Participants then were debriefed, thanked for their participation, and dismissed.

Measures

Participants completed a few unrelated computer tasks. Then, they completed the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale, Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II, Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire, Beck Anxiety Inventory, and State Trait Anxiety Inventory-State Scale as described in Study 1. Participants also completed an additional measure of mindfulness and anxiety.

Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PMS; Cardaciotto Et al., 2008; α = .81–85)

The PMS is a 20-item, bidimensional, self-report measure, which assesses two key components of mindfulness: present-moment awareness (e.g., “I am aware of what thoughts are passing through my mind”; α = .81) and acceptance (e.g., “there are aspects of myself I don’t want to think about”; α = .85). Participants rated their experiences on a scale from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“very often”). Following the recommendations of Cardaciotto et al. (2008), necessary items were reverse coded, and the items for each subscale were averaged. Higher scores indicate greater mindfulness. Both the awareness and acceptance subscales have demonstrated convergent validity with other measures of mindfulness (e.g., Mindful Attention Awareness Scale; Cardaciotto et al., 2008).

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait Scale (STAI-T; Spielberger 1983; α = .91)

The STAI-T is a 20-item self-report instrument that measures trait anxiety. Participants rated the frequency of their anxiety symptoms (e.g., “I worry too much over something that really doesn’t matter.”) on a scale from 1 (“almost never”) to 4 (“almost always”). After reverse scoring positively worded items, responses were summed to create a composite score, as recommended by Spielberger (1983). Higher numbers indicate more trait anxiety.

Results

Means, standard deviations, and alphas for all Study 2 measures are presented in Table 2. The data met all assumptions for the planned analyses, except the BAI was skewed and kurtotic. A square root transformation was conducted to correct for non-normality before conducting the primary analyses. To examine the simple associations among all of the variables, bivariate correlations were calculated (see Table 2). Trait mindfulness was inversely correlated with the experiential avoidance measures, suggesting that individuals who reported higher mindfulness also reported lower experiential avoidance. Trait mindfulness was also inversely correlated with state and trait measures of anxiety. Those who reported higher mindfulness also reported lower state and trait anxiety. Overall, the state and trait anxiety measures were positively correlated with the experiential avoidance measures. Individuals who reported experiencing more anxiety also reported engaging in more experiential avoidance. All of the experiential avoidance measures were positively correlated.

As in Study 1, mediation analyses were conducted to investigate whether experiential avoidance accounted for the association between mindfulness and anxiety using 5000 bootstrapped samples with the PROCESS macro (Preacher and Hayes 2004). Trait mindfulness was entered as the predictor variable, experiential avoidance as the mediator, and anxiety as the criterion variable (see Fig. 1). Separate models were conducted with each individual mindfulness, experiential avoidance and anxiety measures. The patterns of results were generally the same (see Supplemental Tables 3, 4, and 5), so for ease of reporting a single model is presented with composite variables for mindfulness, experiential avoidance, and anxiety. The mindfulness composite consisted of the MAAS, PMS-Acceptance, and PMS-Awareness; the experiential avoidance composite consisted of the AAQ-II and each subscale of the MEAQ; and the anxiety composite consisted of the BAI, STAI-S, and STAI-T. To create the composite variables, scores for each measure were standardized and averaged together.

The overall model explained 35.65% of the variance in anxiety, F(2, 300) = 83.10, p < .001. There was a significant indirect effect of mindfulness on anxiety through experiential avoidance (b = −.30, 95% CI [−.42, −.18]). After including the significant indirect path, the direct effect (b = −.87, p < .001) between mindfulness and anxiety was reduced (b = −.38, p = .003), suggesting that the association between higher mindfulness and lower levels of anxiety was partially accounted for by less experiential avoidance.

Again, an alternative model was tested in which mindfulness was a possible mediator of the relation between experiential avoidance and anxiety. Experiential avoidance was entered as the predictor variable, mindfulness as the mediator, and anxiety as the criterion variable (see Fig. 2). Models utilizing the individual measures were tested and the results were similar (see Supplemental Tables 6, 7, and 8). There was a significant indirect effect of experiential avoidance on anxiety through mindfulness (b = .26, 95% CI [.14, .39]). After including the significant indirect path, the direct effect (b = .67, p < .001) between experiential avoidance and anxiety was reduced (b = .41, p < .001), suggesting that the association between greater experiential avoidance and higher levels of anxiety was partially accounted for by lower mindfulness.

General Discussion

The purpose of these studies was to provide further evidence for the relations among trait mindfulness, anxiety, and experiential avoidance. The extent to which experiential avoidance accounted for the relation between mindfulness and anxiety was also examined. Across both studies, mindfulness was negatively associated with both experiential avoidance and anxiety. Furthermore, there was evidence of significant indirect effects of mindfulness on anxiety through experiential avoidance. These results were found utilizing multiple measures of mindfulness, anxiety, and experiential avoidance, across two different samples, and using different data collection techniques (i.e., online versus in person).

These findings are consistent with prior work suggesting experiential avoidance as a mechanism of action for mindfulness (Brem et al. 2017). We provide additional support for the idea that mindfulness may confer at least some of its benefits in the treatment of anxiety (see, Bach and Hayes 2002; Linehan et al. 1999; Lynch et al. 2003) by reducing experiential avoidance. This finding makes sense because experiential avoidance stands in direct opposition to mindfulness, which promotes an accepting orientation toward the present moment (Bishop et al. 2004).

However, an alternative model in which mindfulness was entered as a mediator between experiential avoidance and anxiety was also supported. These results suggest that more research is needed to fully clarify the relations between these constructs. Indeed, past work has provided evidence for both experiential avoidance and mindfulness as mediators of relations between predictors of anxiety and anxiety symptomatology (Boni et al. 2018; Kroska et al. 2018), as well as for mindfulness as a moderator of the relation between experiential avoidance and anxiety (Raines et al. 2018). The relations among these three constructs are likely complex and bi-directional in nature, thus calling for additional rigorous analyses and use of experimental methodology.

Understanding these relations might help guide clinicians in developing new ways to reduce anxiety through addressing experiential avoidance as a mechanism of therapeutic change. This implication is important because research suggests that anxiety disorders have the highest overall prevalence rate among mental health disorders, with 12 month and lifetime prevalence rates of 18.1% and 28.8% respectively (Kessler et al. 2005a; Kessler et al. 2005b; Olatunji et al. 2007) and experiential avoidance seems to play a role in their etiology (Newman and Llera 2011; Szentagotait 2006). Further, experiential avoidance is pervasive across multiple psychological disorders, such as Substance use disorders, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Panic Disorder, Agoraphobia, Borderline Personality Disorder, and individuals with histories of being sexually abused as children (Hayes et al. 1996).

It is possible that the function of experiential avoidance in psychopathology is partially accounted for by its effects on negative affect and physiological arousal (Campbell-Sills et al. 2006; Weinrib 2011). In an experimental study of emotion regulation within a clinical sample of individuals diagnosed with mood and/or anxiety disorders, Campbell-Sills et al. (2006) found that individuals diagnosed with mood and anxiety disorders, who also attempt to avoid unwanted emotions, experience negative affect for longer periods and greater physiological arousal during emotional events than individuals who accept their emotions. One potential explanation for this is that the avoidant individual now gives greater attentional weight to any stimulus in his or her environment that could be perceived as a threat (i.e., negativity bias), thus eliciting greater physiological arousal and increasing anxiety (Williams et al. 2011). While further work is needed to assess alternate explanatory models, considerable evidence supports the role of experiential avoidance in overall psychopathology. As such, it is imperative that research explore the basic mechanisms by which experiential avoidance is reduced within the context of psychological interventions.

These studies utilized a cross-sectional, correlational design. Thus, causality cannot be inferred from these relations. Experimental research is needed to test for causality in these relations and to provide further evidence for mediation between these constructs. However, this work provides important preliminary evidence for the role of experiential avoidance as a mechanism by which mindfulness could reduce anxiety.

A potential limitation of the present study may be reflected in discrepancies between inter-correlations of MEAQ subscales across the two studies. In Study 1, but not Study 2, the Distress Endurance subscale was inversely correlated with the Distraction and Suppression subscale, such that higher levels of experiential avoidance on one was associated with lower levels of experiential avoidance on the other. This is reflective of mixed results in the literature, in which some studies have reported similarly counter-intuitive relations between these subscales (e.g., Buckner and Zvolenky, 2014; Sahdra et al. 2016) whereas others have observed correlations in the expected direction (e.g., Gamez et al. 2011; Gamez et al. 2014). In future work, alternate scales may be incorporated in order to better establish construct validity of subscales.

Additionally, future research might examine mindfulness, experiential avoidance, and anxiety in clinical samples, so that better inferences might be made regarding the role of mindfulness components in psychotherapy and in more severe forms of anxiety. Both of these studies utilized non-clinical college samples. Therefore, they are limited in the inferences that can be drawn about these relations among individuals who present with a diagnosable anxiety disorder. However, anxiety is a growing problem within college students (e.g., Duffy et al. 2019). Anxiety that does not lead to prolonged dysfunction is common and many of the individuals in the current samples were experiencing this type of anxiety. In Study 1, almost 65% fell within the minimal to mild range of scores on the BAI, suggesting that they are experiencing low levels of anxiety, and 10% fell within the severe range of scores. In Study 2, 83% fell within the minimal to mild range of scores on the BAI and 5% fell within the severe range of scores. Individuals with severe anxiety in the context of anxiety disorders typically experience a prolonged decrease in functionality due to erroneous or exaggerated appraisals of threat, persistent anxiety, and often a hypersensitivity to anxiety-related stimuli (Clark and Beck 2011). Replication of this work in clinical samples could strengthen the evidence for the relations examined in the current study and how they relate to the treatment of anxiety related disorders. Nonetheless, it is also important to examine the relation of these variables in their full range, as can be done in non-pathological community samples like those reported here.

Future work is also needed comparing the efficacy of mindfulness-oriented cognitive and behavioral treatments to traditional cognitive and behavioral therapies in reducing experiential avoidance. Specifically, studies are needed to test whether elements of traditional cognitive and behavioral therapies increase mindfulness without including formal mindfulness training (i.e., exposure therapies, behavioral activation therapies) as well as to assess the active components of mindfulness-oriented treatments. The results of those studies might better inform researchers and practitioners of a specific need for treatments that employ mindfulness training.

Mindfulness has received increased attention over the last two decades, particularly with regard to its therapeutic benefits (Brown and Ryan 2003; Grossman et al. 2004). The present research suggests that trait mindfulness is related to lower experiential avoidance, which may explain how mindfulness reduces anxiety. These findings, while limited to nonclinical samples, have broad implications for future research as they increase our understanding of how treatments that increase mindfulness might affect psychopathology. Given the proposed role of experiential avoidance in the etiology and maintenance of several psychological disorders, interventions and practices that increase mindfulness may have broader mental health benefits as well. However, much more research is needed to examine the relation between mindfulness and experiential avoidance, particularly with clinical populations and in the context of therapeutic interventions.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

American Psychological Association. (2015). Anxiety. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/topics/anxiety/

Antoine, P., Congard, A., Andreotti, E., Dauvier, B., Illy, J., & Poinsot, R. (2018). A mindfulness-based intervention: Differential effects on affective and processual evolution. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-being, 10, 368–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12137.

Bach, P., & Hayes, S. C. (2002). The use of acceptance and commitment therapy to prevent the rehospitalization of psychotic patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1129–1139. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.5.1129.

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bpg015.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., Walsh, E., Duggan, D., & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313003.

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–897. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077.

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., Waltz, T., & Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire - II: A revised measure of psychological flexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42, 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007.

Boni, M., Schutze, R., Kane, R. T., Morgan-Lowes, K. T., Byrne, J., & Egan, S. J. (2018). Mindfulness and avoidance mediate the relationship between yoga practice and anxiety. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 40, 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2018.08.002.

Borkovec, T. D., Alcaine, O., & Behar, E. (2004). Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In R. G. Heimberg, C. L. Turk, & D. S. Mennin (Eds.), Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice. New York: Guilford Press.

Brem, M. J., Shorey, R. C., Anderson, S., & Stuart, G. L. (2017). Experiential avoidance as a mediator of the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and compulsive sexual behaviors among men in residential substance use treatment. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 24, 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2017.1365315.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Briggs, E. S., & Price, I. R. (2009). The relationship between adverse childhood experience and obsessive-compulsive symptoms and beliefs: The role of anxiety, depression, and experiential avoidance. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 1037–1046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.004.

Buckner, J. D., & Zvolenky, M. J. (2014). Cannabis and related impairment: The unique roles of cannabis use to cope with social anxiety and social avoidance. The American Journal on Addictions, 23, 598–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12150.x.

Campbell-Sills, L., Barlow, D. H., Brown, T. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2006). Effects of suppression and acceptance on emotional responses of individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(9), 1251–1263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.001.

Carleton, R. N., Duranceau, S., Freeston, M. H., Boelen, P. A., McCabe, R. E., & Antony, M. M. (2014). “But it might be a heart attack”: Intolerance of uncertainty and panic disorder symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(5), 463–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anxdis.2014.04.006.

Clark, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (2011). Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders: Science and practice. New York: Guilford Press.

Craigie, M. A., Rees, C. S., Marsh, A., & Nathan, P. (2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary evaluation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36, 554–568. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246580800458x.

Cardaciotto, L., Herbert, J. D., Forman, E. M., Moitra, E., & Farrow, V. (2008). The assessment of present-moment awareness and acceptance: The Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Assessment, 15(2), 204–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107311467

Duffy, M. E., Twenge, J. M., & Joiner, T. E. (2019). Trends in Mood and Anxiety Symptoms and Suicide-Related Outcomes Among U.S. Undergraduates, 2007-2018: Evidence From Two National Surveys. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 65(5), 590–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.033

Evans, S., Ferrando, S., Findler, M., Stowell, C., Smart, C., & Haglin, D. (2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 716–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.07.005.

Falkenstrom, F. (2010). Studying mindfulness in experienced meditators: A quasi-experimental approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 305–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.10.022.

Fetzner, M. G., Horswill, S. C., Boelen, P. A., & Carleton, R. N. (2013). Intolerance of uncertainty and PTSD symptoms: Exploring the construct relationship in a community sample with a heterogeneous trauma history. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(4), 725–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-013-9531-6.

Forsyth, J. P., Eifert, G. H., & arrios, V. (2006). Fear conditioning in an emotion regulation context: A fresh perspective on the origins of anxiety disorders. In M. G. Craske, D. Hermans, & D. Vansteenwegen (Eds.), Fear and learning: From basic processes to clinical implications (pp. 133–153). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11474-007.

Gamez, W., Chmielewski, M., Kotov, R., Ruggero, C., & Watson, D. (2011). Development of a measure of experiential avoidance: The multidimensional experiential avoidance questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 692–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023242.

Gamez, W., Chmielewski, M., Kotov, R., Ruggero, C., & Watson, D. (2014). The brief experiential avoidance questionnaire: Development and initial validation. Psychological Assessment, 26, 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034473.

Garland, E. L., Fredrickson, B. L., Kring, A. M., Johnson, D. P., Meyer, P. S., & Penn, D. L. (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Reviews, 30, 849–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002.

Gold, D. B., & Wegner, D. M. (1995). Origins of ruminative thought: Trauma, incompleteness, nondisclosure, and suppression. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 1245–1261.

Goodall, K. E., Trejnowska, A., & Darling, S. (2012). The relationship between dispositional mindfulness, attachment security, and emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences., 52(5), 622–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.008.

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychometric Research, 57, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(03)00573-7.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., Wilson, K. G., Bissett, R. T., Pistorello, J., Toarmino, D., Polusny, M. A., Dykstra, T. A., Batten, S. V., Bergan, J., Stewart, S. H., Zvolensky, M. J., Eifert, G. H., Bond, F. W., Forsyth, J. P., Karekla, M., & McCurry, S. M. (2004). Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record, 54, 553–578.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1152–1168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1152.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Methodology in the social sciences. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Holaway, R. M., Heimberg, R. G., & Coles, M. E. (2006). A comparison of intolerance of uncertainty in analogue obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20(2), 158–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.01.002.

Hou, R. J., Wong, S. Y., Yip, B. H., Hung, A. T., Lo, H. H., Kwok, T. C., et al. (2014). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction program on the mental health of caregivers: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353278.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016.

Kabat-Zinn, J., Massion, A. O., Kristeller, J., Peterson, L. G., Fletcher, K. E., Pbert, L., Lenderking, W. R., & Santorelli, S. F. (1992). Effectiveness of a meditation based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 936–943.

Kashdan, T. B., Zvolensky, M. J., & McLeish, A. C. (2008). Anxiety sensitivity and affect regulatory strategies: Individual and interactive risk factors for anxiety related symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 429–440. doi: 1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.011.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005a). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593−768. Doi:1001/archpsyc.62.6.593.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005b). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 617−709. Doi: 1001/archpsyc.62.6.617.

Kiken, L. , Garland, E. L., Bluth, K., Palsson, O. S., & Gaylord, S. A. (2015). From a state to a trait: Trajectories of state mindfulness in meditation during intervention predict changes in trait mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 81, 41–46. doi: 1016/j.paid.2014.12.044.

Kroska, E. B., Miller, M. L., Roche, A. I., Kroska, S. K., & O’Hara, M. W. (2018). Effects of traumatic experiences on obsessive-compulsive and internalizing symptoms: The role of avoidance and mindfulness. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.039.

Linehan, M. M., Schmidt, H. I., Dimeff, L. A., Craft, J. C., Katner, J., & Comtois, K. A. (1999). Dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug- dependence. American Journal on Addiction, 8, 279–292.

Lynch, T. R., Morse, J. Q., Mendelson, T., & Robins, C. J. (2003). Dialectical behavior therapy for depressed older adults: A randomized pilot study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11, 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/00019442-200301000-00006.

Mayer, B., Polak, M., & Remmerswaal, D. (2019). Mindfulness, interpretation bias, and levels of anxiety and depression : Two mediation studies. Mindfulness, 10, 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0946-8.

Mahoney, C. T., Segal, D. L., & Coolidge, F. L. (2015). Anxiety sensitivity, experiential avoidance, and mindfulness among younger and older adults : Age differences in risk factors for anxiety symptoms. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 81, 217–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415015621309.

Newman, M. G., & Llera, S. J. (2011). A novel theory of experiential avoidance in generalized anxiety disorder: A review and synthesis of research supporting a contrast avoidance model of worry. Clinical Psychology Review, 3, 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.008.

Olatunji, B. O., Cisler, J. M., & Tolin, D. F. (2007). Quality of life in the anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(5), 572–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.015.

Pepping, C. A., Duvenage, M., Cronin, T. J., & Lyons, A. (2016). Adolescent mindfulness and psychopathology: The role of emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 302–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.089.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03206553.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316.

Quaglia, J. T., Braun, S. E., Freeman, S. P., McDaniel, M. A., & Brown, K. W. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for effects of mindfulness training on dimensions of self-reported dispositional mindfulness. Psychological Assessment, 28, 803–818. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000268.

Raines, E. M., Rogers, A. H., Bakhshaie, J., Viana, A. G., Lemaire, C., Garza, M., Mayorga, N. A., Ochoa-Perez, M., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2018). Mindful attention moderating the effect of experiential avoidance in terms of mental health among Latinos in a federally qualified health center. Psychiatry Research, 270, 574–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.036.

Sahdra, B. K., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P., & Scrucca, L. (2016). Using genetic algorithms in a large nationally representative American sample to abbreviate the multidimensional experiential avoidance questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00189.

Sloan, D. M. (2004). Emotion regulation in action: Emotional reactivity in experiential avoidance. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 1257–1270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.006.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1970). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Spielberger, C. D. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Szentagotait, A. (2006). The paradoxical effects of suppressing anxious thoughts. Cognition, Brain, Behavior, 10, 599–610.

Tomlison, E. R., Yousaf, O., Vitterso, A. D., & Jones, L. (2018). Dispositional mindfulness and psychological health : A systematic review. Mindfulness, 9, 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0762-6.

Tull, M. T., Gratz, K. L., Salters, K., & Roemer, L. (2004). The role of experiential avoidance in posttraumatic stress symptoms and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and somatization. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(11), 754–761.

Vowles, K. E., Fink, B. C., & Cohen, L. L. (2014). Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: A diary study of treatment process in relation to reliable change in disability. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 3(2), 74–80.

Weinrib, A. Z. (2011). Investigating experiential avoidance as a mechanism of action in a mindfulness intervention. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Iowa, Iowa City. http://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2489&context=etd

Wegner, D. M., Schneider, D. J., Carter, S. R., & White, T. L. (1987). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.1.5.

Williams, L., Gatt, J., Schofield, P., Olivieri, G., Peduto, A., & Gordon, E. (2011). Negativity bias in risk for depression and anxiety: Brain-body fear circuitry correlates, 5-HTT-LPR and early life stress. Neuroimage, 47(3), 804–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.10.001.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of West Virginia University. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 47 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McCluskey, D.L., Haliwa, I., Wilson, J. et al. Experiential avoidance mediates the relation between mindfulness and anxiety. Curr Psychol 41, 3947–3957 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00929-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00929-4