Abstract

Mindfulness-based interventions are thought to attenuate stress and anxiety while improving focus and awareness. College students are at risk for and often experience increased stress and anxiety. Consequently, college students may benefit from mindfulness-based interventions. The purpose of this systematic review of the qualitative literature was to understand and explain how college students perceive and depict mindfulness-based interventions. A thematic synthesis approach was used to analyze the literature. Nineteen qualitative studies were included, and four overarching themes identified: awareness, barriers to meditation, improved focus, and facilitator’s role. Awareness included three subordinate themes: emotion regulation, tools for future use, and relationship with others. Students stated that mindfulness-based interventions were overall beneficial and described them as a coping mechanism that attenuated their stress, anxiety, and emotions, improved learning, build relationships, and provided tools for future careers. Findings of this synthesis indicate that mindfulness-based interventions should be developed that specifically meet the needs of college students. Moreover, future researchers should examine the component of mindfulness-based interventions that students perceived as most beneficial and the differences in perceptions based on college major. Our review is a bridge to understanding the vital components of mindfulness-based interventions in college students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Excessive stress and anxiety are major dilemmas on college campuses today, breeding such problems as poor academic performance, illness, attrition, and depression (Hughes 2005; Oman et al. 2008; Draper-Clarke and Edwards 2016; Kerrigan et al. 2017). There has been a rise in college student stress, anxiety, and depression over the last 14 years and in some cases, rates have doubled (American College Health Association 2015). Approximately 20% of first-time, first-year, college students, will not advance to their sophomore year and only 59% of first-time college students will graduate within 6 years (National Center for Education Statistics 2014).

Within the last two decades mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been growing in popularity to attenuate stress and anxiety while improving focus and awareness (Astin 1997; Shapiro et al. 1998; Demarzo et al. 2014; Bamber and Morpeth 2019). Mindfulness-based Interventions (MBIs) are being used in many colleges in hopes to decrease negative psychological symptoms and attrition, while increasing academic achievement (Yamada and Victor 2012; Bond et al. 2013; Ramasubramanian 2016). However, there are a multitude of MBIs available, including mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), acceptance-based behavioral therapy (ABBT), Kouk Sun Do, and many researcher created interventions.

Many interventions exist to reduce stress and anxiety, such as physical exercise, yoga, and journaling; however, none of these interventions are focused on changing thought processes, self and situational awareness, focus, and emotional reactivity. Awareness, acceptance, non-judgmental thoughts, non-reactivity, and control of attention characterize MBIs and practitioners’ perceived experience with each are essential to understanding the impact of MBIs (Bishop et al. 2004; Carsen and Langer 2006; Kabat-Zinn 2006; Malinowski 2013; Neuser 2010; Rapgay and Bystrisky 2009; White 2014). Researchers have employed MBIs with college students with success; moreover, qualitative studies have been conducted to better understand college students’ perceptions of benefits and barriers to MBIs. Understanding the effectiveness and perceptions of MBIs is essential because a “one size fits all” approach does not work in mental health or education; therefore, we cannot assume standardized MBIs would work for all college students. To construct interventions, health care professionals, researchers, and educators must understand the development, diversity, culture, life experiences, preferences, and interests of those they target (Gregory and Chapman 2013; Alegria et al. 2010; Lyzwinski, Caffery, Bambling, and Sisria, 2018). For example, Watson et al. (2016) reported that African American women were afraid to tell their peers they practiced meditation because of the cultural stigma associated with meditation. College students may perceive and value MBIs differently than other populations. Once researchers understand students’ perceptions and values of the target population, then appropriate MBIs can be tailored to fit their specific needs. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review of the qualitative literature was to understand how college students perceive and describe MBIs, including what they believe to be the benefits of and barriers to MBIs.

Methods

Inclusion Criteria

All MBI studies with a college student population that reported qualitative data were included in this review. We included only studies where researchers analyzed qualitative data of college students’ perceptions and experiences post-MBIs for stress and anxiety. We included mixed-methods studies, dissertations, and other non-published materials. We included studies of college students of all ages, genders, and levels of academic study. Studies were excluded if they were not written in English and if they did not include a qualitative component Pre-intervention perceptions and expectations of MBIs were also excluded.

Search Criteria

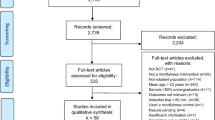

We conducted a thorough systematic search of multiple databases using the following search terms: “mindful*” AND “college OR universit*” AND “stress” OR “anxiety.” Subject headings were exploded to include more potential articles. Seven medical and psychology databases were searched and included: MEDLINE, Scopus, PsychINFO, PubMed, Cochrane, CINAHL, and Campbell Library. Database searches resulted in 652 studies, including 8 dissertations. Ancestry and hand searches resulted in four additional studies. After duplicates were removed, 190 studies remained. Abstracts were screened for eligibility and 170 were removed for quantitative methodology or non-English language. Twenty qualitative studies remained, and full-text versions were read for inclusion. Further review resulted in exclusion of six studies; two case studies, two that focused on athletic performance, one mixed method with no clear description of the qualitative outcomes, and one study that used mantra meditation, not MBIs. A second search of the databases were conducted which resulted in 658 studies, including 5 dissertations. After duplicates were removed and abstracts screened for inclusion, 13 studies remained. After full-text screening, an additional 9 studies were excluded; five did not explore students’ perceptions of MBIs, three focused on athletic performance, one used mediyoga (a combination of meditation and yoga done together), and one did not include college students. After both searches, 18 studies remained for inclusion in this review.

Results

Study Characteristics

Of the 18 qualitative studies included in this review, four research teams used phenomenology with sample sizes of 7, 10, 20, and 22; four used grounded theory with samples of 8, 12, 27, and 40; and five used thematic analysis with sample sizes of 24, 29, 23, 20, and 18; two used conventional content analysis, with sample sizes of 41 and 17; two used inductive content analysis, with sample sizes of 28 and 21, and one reported their methodology as an exploratory pilot study, with a sample size of 13. Table 1 describes the purpose, design, intervention, identified themes, and analysis of each article in this review. Participants in nine of the studies were in helping professions, such as; occupational therapy, social work, healthcare, and medicine. Researchers in four studies stated undergraduate students were used, but disciplines were not reported. Researchers in four studies reported using undergraduate and graduate students or did not differentiate. The final study, researchers used students in a communications program.

Researchers used a variety of MBIs in their studies. Researchers in seven studies used MBSR or a modified MBSR (Birnbaum 2008; Stew 2011; Gockel et al. 2013; Felton et al. 2015; Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Solhaug et al. 2016; Kerrigan et al. 2017). Nine researcher teams used researcher created MBIs or described the meditations as mindfulness meditations (Parish 2011; Bond et al. 2013; Lauricella 2013; Johnson 2016; Beck, Vertucchio, Seeman, Milliken, & Schaab, 2017; Crowley and Munk 2017; Ramasubramanian 2016; Schwind et al. 2017; Kindel 2018), one research team used Mindfulness Awareness Training (Shonin et al. 2013) and one research team used Kouk Sun Do (Kim et al. 2013). Interventions varied from four to 15 weeks, with one to seven sessions per week, and each session lasting five minutes to two hours. Two research teams used an extended, either half or full day session (Johnson 2016; Solhaug et al. 2016), one research team had three sessions spaced out over 15 weeks, (Crowley and Munk 2017), and one researcher had two session lasting 30 min each (Lauricella 2013).

Study Findings

Despite the significant differences in the interventions, outcomes in all 18 studies were favorable. Fifteen research teams identified themes during analysis, which ranged from two to eight. Three research teams did not specify themes during analysis (Gockel et al. 2013; Lauricella 2013; Schwind et al. 2017). Researchers in all studies reported in their themes or outcomes that MBIs increased awareness and emotional regulation. Seven research teams specifically reported students had increased self-acceptance (Bond et al. 2013; Shonin et al. 2013; Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Felton et al. 2015; Johnson 2016; Solhaug et al. 2016). Moreover, 12 research teams reported that MBIs decreased student stress and anxiety, increased their ability to stay calm, relaxed, rested and improved their overall emotional wellbeing (Parish 2011; Bond et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2013; Lauricella 2013; Shonin et al. 2013; Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Solhaug et al. 2016; Beck et al. 2017; Kerrigan et al. 2017; Ramasubramanian 2016; Schwind et al. 2017; Kindel 2018).

Researchers reported that MBIs led to improved focus and academic abilities. Improved concentration, focus, and organization was an outcome or theme reported by 10 research teams (Birnbaum 2008; Parish 2011; Gockel et al. 2013; Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Johnson 2016; Solhaug et al. 2016; Beck et al. 2017; Ramasubramanian 2016; Schwind et al. 2017; Kindel 2018). Improvements in learning or overall academic ability was reported by five research teams (Parish 2011; Stew 2011; Gockel et al. 2013; Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Kerrigan et al. 2017). Furthermore, researchers also reported that MBIs gave them tools that they could use in the future, either with future patients or for themselves. Seven research teams reported themes or outcomes where students stated they would use mindfulness techniques with their patients or for themselves in the future (Birnbaum 2008; Stew 2011; Bond et al. 2013; Gockel et al. 2013; Felton et al. 2015; Beck et al. 2017; Kindel et al. 2018).

Researchers reported that students often reported that participating in MBIs was a positive experience, increased their happiness, improved their relationships and compassion, and gave them a greater sense of comradery with classmates. Parish (2011), Shonin et al. (2013), and Beck et al. (2017), reported that students had positive experiences with MBIS and Ramasubramanian (2016) reported that MBIs increased students’ happiness. Birnbaum (2008) reported that students made coincidental choices of meditation themes among group members. Bond et al. (2013) and Hjeltnes et al. (2015) reported that students found comradery within competitive environments and with those that shared the same problems as themselves. Likewise, nine research teams reported that students had improved compassion and relationships after participating in MBIs (Birnbaum 2008; Lauricella 2013; Shonin et al. 2013; Felton et al. 2015; Johnson 2016; Solhaug et al. 2016; Crowley and Munk 2017; Kerrigan et al. 2017; Ramasubramanian 2016).

Conversely, researchers in several studies reported barriers to MBIs. Birnbaum (2008), Stew (2011), Johnson (2016), Schwind et al. (2017) reported that students were either ambivalent about meditation or lacked confidence in their ability to meditate. Moreover, Parish (2011), Stew (2011), Solhaug et al. (2016), and Kindel (2018) reported that students had difficulty finding time to meditate outside of the scheduled sessions. Ramasubramanian (2016) reported some students found no difference in their wellbeing after the MBI. Several research teams reported on the importance of the MBI facilitator. Four reported that the facilitator was invaluable to the students’ experience (Lauricella 2013; Shonin et al. 2013; Schwind et al. 2017; Kindel 2018). Contrary to these outcomes, Kim et al. (2013) reported that the role of the facilitator was not significant in the outcomes of the MBIs.

Researchers reported several implications. Many reported that MBIs would be beneficial if they were incorporated into universities and a variety of curriculums (Birnbaum 2008; Parish 2011; Stew 2011; Gockel et al. 2013; Lauricella 2013; Crowley and Munk 2017; Kerrigan et al. 2017). They also reported the need for further research on the influence of gender, culture, age, rank in college, and major of study (Johnson 2016; Crowley and Munk 2017; Ramasubramanian 2016). Furthermore, researchers’ implications noted further need for evaluation of the delivery method, long-term effects, overall credibility of curriculum implemented programs, and facilitator training (Bond et al. 2013; Lauricella 2013; Shonin et al. 2013; Johnson 2016; Crowley and Munk 2017; Ramasubramanian 2016; Schwind et al. 2017). Finally, researchers recommended further research exploring MBIs and performance anxiety, general mental health, and relationships between MBIs, communication, stress, coping and academic flexibility (Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Ramasubramnian 2017).

Synthesis Method

We used the thematic synthesis approach to interpret and analyze characteristics from each study. We used this method because it allowed us to address intervention concerns and suitability (Barnett-Page and Thomas 2009). Articles were read, and results presented in the articles were independently coded. Then we discussed our codes and came to consensus. Next, we developed themes that described the coded text (Thomas and Harden 2008). Through further discussion, we determined that some themes were subsumed under broader themes. Thematic synthesis approach allowed for comparison throughout analysis. After carefully reading, analyzing, comparing, and discussing studies for similarities and differences, we agreed upon four overarching themes. These themes included: awareness, barriers to meditation, improved focus, and facilitator’s role.

Themes

The first of the four over-arching themes that became apparent during analysis was awareness. Awareness is described as consciousness of mental and physical perceptions. During thematic synthesis, we believed that several themes should be subsumed under awareness. The subordinate themes were recognized because of a greater self-awareness experienced by the students. These subordinate themes were named: emotion regulation, tools for future use, and relationship with others. The second theme, barriers to meditation, reflected students’ perceptions of difficulties to practicing MBI’s. The third theme, improved focus, reflected students greater mental focus after participating in MBIs. The final theme, facilitators’ role, reflected the importance of MBI instructors. The themes are further described below.

Awareness

The most common student perception of MBIs was increased awareness, which was reported in all 18 studies. Through meditative practice students became aware of their countless thoughts and sensations and found they were able to gain control over these thoughts (Stew 2011). Participants reported a growth in ‘present moment awareness’. This was often expressed in terms of feeling joy due to being aware of the “here and now” and how to “live their life better” (Shonin et al. 2013, p. 854; Ramasubramanian 2016, p. 316). Shonin et al. (2013) also stated that students gained awareness and control of their various thoughts through MBIs. They reported that once awareness developed, they learned to be present in the moment (Shonin et al. 2013). Students reported that MBIs increased their awareness of thoughts, feelings, and emotions Students reported that they were able to “reconnect” with their thoughts and bodily sensations throughout the day with short informal meditations (Kerrigan et al. 2017; Johnson 2016; Parish 2011; Beck et al. 2017). Moreover, students reported that mindful showers and body scans were helpful because it focused their awareness on sensations of water hitting their bodies and specific muscle tension respectively, increasing the mind-body connection (Johnson 2016; Kindel 2018). This awareness promoted understanding and aided students’ attentiveness while studying and organizing their coursework (Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Parish 2011).

Students also described awareness of the connection between mind and body. They reported an increase in awareness of bodily sensations and responses to these sensations (Bond et al. 2013; Johnson 2016; Kindel 2018). Researchers reported that nearly all students were more aware of their physical and mental sensations and that they experienced increased calm, tranquility, and were in harmony with their bodies (Johnson 2016; Ramasubramanian 2016; Beck et al. 2017; Kindel 2018). Stew (2011) stated, “This sense of self-inquiry...can awaken a desire for authenticity and a connection with an inner self” (p. 272). Self-inquiry is a continual attention to the inner-self, asking ones-self ‘who am I’, until awareness of the true self is realized (Sattler 2011). The practice of self-inquiry led the students to develop self-awareness and allowed them to grasp the physical and psychological sensations they were experiencing, which led to greater mind-body awareness and true self-evaluation. Once self-awareness was realized, through self-inquiry, students reported the ability attenuate their responses to unpleasant sensations and situations (Bond et al. 2013; Kindel 2018).

Emotion Regulation

In all 18 studies, researchers reported that students learned to regulate their emotions and improve their coping ability. Researchers’ comments that reflected the ability to regulate emotions were coded under the subsumed theme, emotion regulation. Students’ believed they became more self-aware and could acknowledge and understand sensations within their own bodies, which increased their ability to control their reactions (Bond et al. 2013; Kindel 2018). They learned to maintain awareness regardless of perceived sensations and to “observe from within, despite the challenge of simultaneously” experiencing intense “physical” and psychological “sensations” while “noting possible relationships between them” (Birnbaum 2008, p. 843). Students also reported that participation in MBIs increased their awareness of when academic anxiety began to distract them from their performance or new stress building. Students were able to use that awareness to refocus their attention to the task at hand or eliminate the perceived stress before it became overwhelming (Felton et al. 2015; Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Kerrigan et al. 2017; Schwind et al. 2017; Ramasubramanian 2016). Additionally, students reported they were able to control their emotions after a stressful day using MBI techniques (Beck et al. 2017). They reported that MBIs enabled their ability to contain reactions to strong emotional stimuli and accepted themselves and their feelings, while maintaining emotional security, despite experiencing distress (Shonin et al. 2013; Solhaug et al. 2016; Kindel 2018). Similarly, students stated they were better able to “respond appropriately to the situation at hand” (Stew 2011, p. 273), reply to situations with non-reactivity, and manage difficult situations. This emotional and non-reactivity control enhanced their ability to manage stress and anxiety, including in the clinical setting (Bond et al. 2013; Gockel et al. 2013; Johnson 2016; Kindel 2018). Correspondingly, students reported that they were more calm, relaxed, and peaceful after MBI training. Researchers reported that MBIs left them joyful, optimistic, and grateful for the experiences. These tranquil emotions allowed them to attenuate, regulate, and control their overall emotions (Crowley and Munk 2017; Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2013; Lauricella 2013; Parish 2011; Solhaug et al. 2016; Ramasubramanian 2016).

Tools for the Future: Self and Patients

Students in the helping professions reported that MBIs helped them in their professional clinical practice (Bond et al. 2013; Gockel et al. 2013). We coded these outcomes under the sub theme termed, tools for the future: self and patients. This subordinate theme was coded in seven of the 18 articles. Gockel et al. (2013) stated, “the use of mindfulness in the classroom helped to affirm the continuing importance of the practice in relation to their new professional role” (p. 350). Students reportedly coached their patients to use MBIs and would use it themselves before the onset of therapeutic sessions (Bond et al. 2013; Kindel 2018). Students taught their patients MBIs, providing them with an additional coping mechanism (Bond et al. 2013) “to support themselves and their patients” (Stew 2011, p.273).

Students believed that MBIs increased their ability to empathize with and be more present for their patients. Felton et al. (2015) reported that mindfulness training increased the students, “ability to be present with clients” (p. 165). They also found that they had an improved therapeutic relationship with their patients because of decreased reactivity to strong or difficult emotions while working with their patients (Felton et al. 2015; Gockel et al. 2013; Beck et al. 2017). Gockel et al. (2013) states, “Thus, mindfulness practice appeared to help this group of novice trainees make more conscious and deliberate choices about their responses to clients in session” (p.349). The ability to use MBIs in the future for themselves was appealing, “Clearly they were interested in such tools for future use as well” (Birnbaum 2008, p.841) and students stated, it would be beneficial to start their days off with meditation. They also reported that with the various ways there were to meditate, it allowed the students to choose which method worked best for them (Beck et al. 2017; Kindel 2018). Students believed that MBIs better prepared them for practice by increasing their confidence and decreasing anxiety (Bond et al. 2013; Kindel 2018). Medical students came to understand the importance of the mind-body connection within overall health status and gained confidence in recommending alternative therapies to their patients (Bond et al. 2013). MBIs changed the way medical students viewed medicine in general, creating a more holistic view of health.

Relationship with Others

Researchers reported in 11 of the 18 studies that students’ relationships with others, whether classmates, instructors, clients, or friends were impacted by MBIs (Birnbaum 2008; Bond et al. 2013; Crowley and Munk 2017; Felton et al. 2015; Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Kerrigan et al. 2017; Lauricella 2013; Shonin et al. 2013; Solhaug et al. 2016; Johnson 2016; Ramasubramanian 2016). These relationships and outcomes were coded under the secondary theme, relationship with others. Students were more likely to critically examine their relationships with others after participating in MBIs and were able to determine how those relationships affected their lives, which created an increased self-awareness. Students attempted to understand the significance and implications of relationships with teachers and others within their new professional role, while being more perceptive to feelings and needs of others and gaining “greater autonomy within relationships” (Shonin et al. 2013, p. 859), a “greater social connection” (Crowley and Munk 2017, p. 95), increased ability “to enjoy activities” (Kerrigan et al. 2017, p. 913), “focus on being more kind” (Ramasubramanian 2016, p. 316), and “greater sense of their common humanity” (Johnson 2016, p.145) with others (Birnbaum 2008). They used awareness to identify their feelings towards, and the role of, influential individuals in shaping their professional self (Birnbaum 2008; Johnson 2016l). Students initially compared their progress with others and the belief that others were advancing faster. This motivated the group to practice (Kerrigan et al. 2017; Shonin et al. 2013). Medical students experienced an increase in friendships in what is usually a very competitive environment (Bond et al. 2013). MBIs enabled them to acknowledge and understand their competitive natures and find a greater sense of community. Moreover, students reported they felt “less alone with their performance anxiety”, knowing that other students were dealing with the same issues (Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Johnson 2016). Students reported they were better able to examine their relationships, that they had enhanced personal relationships, and gained a sense of security and understanding through these relationships after participation in MBIs (Solhaug et al. 2016; Johnson 2016).

Barriers to Meditation

Barriers to meditation was described as any perception that prevented students from participating fully in MBIs. Researchers reported barriers to meditation in 9 of the 18 studies. Students experienced three barriers to meditation: ambivalence, time to meditate, and anxiety/fear of meditation. A majority reported that students experienced ambivalence about MBIs, found it difficult to incorporate MBI into their daily routine, or that MBI practice increased their anxiousness (Birnbaum 2008; Kerrigan et al. 2017; Parish 2011; Schwind et al. 2017; Stew 2011; Solhaug et al. 2016; Johnson 2016; Ramasubramanian 2016; Kindel 2018). Ambivalence towards meditation “was an internal struggle raging over the extent to which students should have allowed themselves to go along with the experience, and over its consequences” (Birnbaum 2008 p. 844). Students reported that they had no change after MBIs and that they possibly did not put forth enough effort in MBI practice which increased their ambivalence and anxiety (Ramasubramanian 2016). Time was a major barrier in committing to MBIs homework. Some students reported that it was not worthwhile given opposing responsibilities and often believed they were not productive if they spent time meditating (Kerrigan et al. 2017; Solhaug et al. 2016; Johnson 2016; Kindel 2018). Researchers also reported that students found it arduous to commit to the meditative homework, thought it too reminiscent of academics, and that homework practice sessions left them feeling uncertain, unsure, and tentative (Schwind et al. 2017; Stew 2011; Solhaug et al. 2016). While other students agreed that finding time for MBIs practice was challenging, they also felt guilty when they forwent practice. However, to prevent the feelings of guilt, researchers encouraged them to bring mindfulness to everyday tasks (Parish 2011; Stew 2011; Solhaug et al. 2016).

Improved Focus

Improved focus was a theme found in 12 of the 18 studies. Improved focus is described as the ability to maintain focus on current tasks without the mind wandering. “Several [students] spoke of the ability to use mindfulness to concentrate more easily on mental tasks” (Parish 2011, p.273). They believed that MBIs fostered their ability to focus while studying, which made studying easier. They were also able to focus when they were troubled by academic anxiety or while taking exams (Hjeltnes et al. 2015; Schwind et al. 2017; Stew 2011). They reported that if their mind wandered during tasks, they were able to bring the focus back to the tasks at hand (Kindel 2018). Moreover, researchers reported that students had greater present moment focus and were able to focus on a single thought, which allowed them to complete tasks easily and without distractions (Johnson 2016; Ramasubramanian 2016; Beck et al. 2017; Kindel 2018). During class, students stated they perceived less anxiety and increased focus, which resulted in higher work productivity (Birnbaum 2008; Gockel et al. 2013; Kerrigan et al. 2017; Solhaug et al. 2016; Kindel 2018). Finally, students reported they were more relaxed and less anxious during testing which allowed them to be “more careful and thorough on tests” (Parish 2011, p. 56) or “more present…taking difficult exams” (Hjeltnes et al. 2015).

Facilitator’s Role

Facilitator’s role was described as students’ perceptions of interactions with facilitators, the facilitators’ roles, or the facilitators themselves. The role of the facilitator was coded in five of 18 studies. Students reported that interactions with MBIs facilitators were essential in the development of mindfulness skills. They recognized the importance of supportive practices and facilitators (Shonin et al. 2013). “The role of the facilitators was described as ‘essential’ and their execution of the role as ‘inspiring’” (Shonin et al. 2013, p.856). Additionally, “the face-to-face exercise was more effective because they preferred the personal connection with the instructor” (Lauricella 2013, p. 685). Moreover, “the tone of voice and pacing of guiding mindfulness impacted their experience” (Schwind et al. 2017, p. 94) and that an “authentic teacher” made MBIs more appealing for participation (Kindel 2018, p. 150). Contrarily, Kim et al. (2013) reported that MBIs was a self-induced method of relaxation. Therefore, they did not require facilitation by trained individuals or external guidance. Kim et al. (2013) did not report if students perceived the facilitators’ role as important or if this role was necessary to achieve their MBIs goals.

Discussion

We identified four overarching themes: awareness, barriers to meditation, improved focus, and facilitators’ role. Future researchers and those implementing MBIs should recognize perceived benefits of MBIs and design interventions/programs to meet the unique needs of college students. Students believed that practicing MBIs increased their awareness of thoughts, feelings, sensations, and surroundings. The newfound awareness enabled their understanding and acceptance of challenges, allowed them to examine relationships, and care for patients, all while regulating emotions and experiencing reduced distress. Additionally, when faced with an unpleasant task, sensation, or life event, they approached it with a calm, rational demeanor. The awareness that developed gave students a sense of “peace and calm” (Shonin et al. 2013; Ramasubramanian 2016). Students were able to critically evaluate their thought processes and understand more clearly what their lives and life experiences meant to them.

Awareness of emotions and sensations helped students discriminate between negative and positive behaviors (Stew 2011; Kindel 2018). Correspondingly, students must become aware of their thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations to acquire the ability to regulate their emotions (Birnbaum 2008; Stew 2011; Kindel 2018). Self-awareness supports acceptance and calm management of unpleasant situations. The findings reported in this synthesis are essential to consider when developing and implementing MBIs for college students. Mindfulness-based interventions for college students, not unlike the general population, should primarily focus on awareness, because awareness was perceived by students as the most beneficial outcome. Awareness during MBIs could come from several forms of meditation: awareness of breath meditations, thoughts meditations, walking meditations, shower meditations, and/or eating meditations. Each of these types of meditations bring awareness to the present moment. Guiding students to remain aware of the present moment can help them understand and regulate thoughts, feelings, and emotions; which will then help them in academics, future work, and professional and personal relationships. This qualitative synthesis supports MBIs to improve awareness and emotional regulation in college students. It is important to note that emotion regulation requires internal self-awareness; the cognizance of thoughts and feelings that are experienced.

Many Interventions have been used with college students attempting to improve wellbeing and decrease stress and anxiety. These range from physical exercise, journaling, yoga, coloring, etc. Each of these interventions can be beneficial in some way. However, none of these interventions are developed to change thought processes. Mindfulness-based interventions change practitioners thought process, which makes them more aware of self and improves their situational awareness, focus, and emotional reactivity. Moreover, many of these interventions require practitioners to set aside time to complete; conversely, MBIs exist that can be completed while eating, showering, walking, and driving. The change in thought processes and the ease of which MBIs can be integrated into daily routines makes MBIs an optimal intervention for the college student population.

Implications

The addition of MBIs into a daily routine may be arduous to college students; this must be considered when designing interventions specifically for college students. They frequently have demanding schedules that prohibit the inclusion of formal MBIs. To encourage college students to integrate MBIs into daily routines, interventions may need to be altered to better fit their schedules. Length of the interventions were not addressed. Students initially experienced a sense of being overwhelmed (as a barrier); but were eventually able to incorporate MBIs into their daily routines. Students perceived two main barriers that must be considered when developing MBIs; time and ambivalence. Students with heavy school workload may feel overburdened and ambivalent about learning to practice MBIs. Future researchers should examine the length of time it takes for students to no longer feel overwhelmed with MBIs. Moreover, intervention implementation should be scheduled around their school workload and they should be given practical guidance on implementing MBIs into daily practice; such as those that can be done while driving, walking, showering, and eating. If this is not done effectively, students may not practice or become adept at MBIs and therefore, not benefit from the intervention. Students beginning MBIs should be presented with potential benefits of MBIs. They may be more apt to continue and be consistent with MBIs practice if presented with outcomes of continued practice; increased ability to concentrate, focus, and academic performance, while decreasing their perceived distress.

Learning is impaired by excessive levels of stress and anxiety, which hinders attentiveness, recall, and critical thinking, leading to poor academic performance, burnout, and attrition (Kitzrow 2003; Beddoe and Murphy 2004; Morgan 2016). MBI research supports claims that it can improve concentration and focus, enhancing overall learning. Mindfulness-based interventions could be structured into college orientations, course electives, and organization activities. For example, during college orientation, new students could be given brief instruction on MBIs focused on awareness, such as awareness of breath, which can be practiced during tests, while studying, or at any other perceived stressful event. Students should be informed that if they begin to feel ambivalent and inundated, that this is normal and expected, but with continued practice, they will move beyond those feelings and experience the benefits that MBIs have to offer.

Nonetheless, researchers should explore differences in MBI experiences between those in helping professions and students in other majors with different perceived stresses and anxieties. Most researchers of the studies used in this synthesis used students in helping professions (i.e. social work, physical therapy, medicine, etc.). Students in other majors may experience MBIs differently than those in the helping majors.

Lastly, MBIs for college students should be facilitator led. While there was limited evidence of the importance of facilitators, those that did examine this role found that students perceived facilitator led interventions more effective than self-led. Additionally, they found facilitators to be motivating influences to continued practice (Lauricella 2013; Shonin et al. 2013; Schwind et al. 2017; Kindel 2018). College students found value in relationships they had with their facilitators; therefore, facilitators should offer students the ability to ask questions and seek guidance when experiencing ambivalent feelings. Student should be able to use the facilitators as role models for their own practices. Nevertheless, future researchers should explore the need for facilitators since there are several phone applications, compact discs, online video, and computer led MBI programs available that may be used in place of facilitators. Future researchers might determine how facilitators influence outcomes of MBIs.

Limitations

This review had several limitations. There were a limited number of studies included in this review which could have influenced our thematic analysis of the literature. While an extensive literature search was conducted there is still potential for missed data. However, even with the limited number of articles synthesized in this review we saw the same themes emerging across studies. Additionally, this review relies solely on the feedback of students and their perceptions of MBIs. Finally, this review is a thematic synthesis, which requires reviewers to examine the original researchers’ themes and create analytic themes. We potentially could have misinterpreted the original themes of our analysis; however, we independently coded the themes and discussed to come to consensus.

Conclusion

This synthesis will help guide future MBIs design, implementation, and research in the college student population. The results can be used to begin to develop MBIS that are suitable, appropriate, and specifically designed for stress and anxiety in college students. Students reported that MBIs were difficult to incorporate into their busy schedules and preferred face-to-face contact with facilitators. Researchers should consider the importance in devising MBIs that are facilitator led and not perceived as overly time consuming. Mindfulness-based interventions were perceived to improve the students’ ability to increase awareness and regulate emotion. The ability to focus and learn was enhanced after completing the MBIs. Researchers should further explore these outcomes to determine if MBIs has potential to decrease attrition and improve academic outcomes.

Through this thematic synthesis we have discerned several important characteristics of MBIs that must be accounted for when developing interventions or programs geared toward college students. A phenomenon is occurring with MBIs, and programs are being implemented on many college campuses, classrooms, and communities. Due to the sweeping rise in MBIs, it is essential that we implement programs that fit the lives of the population that is using them. Our review is a small piece in understanding the essential components needed in MBIs for college students.

References

Alegria, M., Atkins, M., Farmer, E., Slaton, E., & Stelk, W. (2010). One size does not fit all: Taking diversity, culture and context seriously. Administration and Policy in Meath Health, 37(1–2), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-D10-0283-2.

Astin, J. A. (1997). Stress reduction through mindfulness meditation: Effects on psychological symptomatology, sense of control, and spiritual experiences. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 66(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1159/000289116.

Bamber, M. D., & Morpeth, E. (2019). Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on College Student Anxiety: a Meta-Analysis. Mindfulness, 10(2), 203–214.

Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(59). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59.

Beck, A. R., Verticchio, H., Seeman, S., Milliken, E., & Schaab, H. (2017). A Mindfulness Practice for Communication Sciences and Disorders Undergraduate and Speech-Language Pathology Graduate Students: Effects on Stress, Self-Compassion, and Perfectionism. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26(3), 893–907.

Beddoe, A. E., & Murphy, S. O. (2004). Does mindfulness decrease stress and foster empathy among nursing students? The Journal of Nursing Education, 43(7), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20040701-07.

Birnbaum, L. (2008). The use of mindfulness training to create an ‘accompanying place’ for social work students. Social Work Education, 27(8), 837–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470701538330.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., ….Devins, G., (2004) Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077.

Bond, A. R., Mason, H. F., Lemaster, C. M., Shaw, S. E., Mullin, C. S., Holick, E. A., & Saper, R. B. (2013). Embodied health: The effects of a mind-body course for medical students. Medical Education Online, 18, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v18i0.20699.

Carsen, S., & Langer, E. (2006). Mindfulness and self-acceptance. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 24(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-006-0022-5.

Crowley, C., & Munk, D. (2017). An examination of the impact of a college level meditation course on college student well being. College Student Journal, 51(1), 91–98.

Demarzo, M.M.P., Andreoni, S., Sanches, N., Perez, S., Fortes,S., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2014) Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in perceived stress and quality of life: An open, uncontrolled study in a Brazilian healthy sample. Explore, 10(2), 118–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2013.12.005.

Draper-Clarke, L. J., & Edwards, D. J. (2016). Stress and coping among student teachers at a South African university: An exploratory study. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 26(6), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2016.1250425.

Felton, T., Coates, L., & Christopher, J. C. (2015). Impact of mindfulness training on counseling students' perceptions of stress. Mindfulness, 6(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0240-8.

Gockel, A., Burton, D., James, S., & Bryer, E. (2013). Introducing mindfulness as a self-care and clinical training strategy for beginning social work students. Mindfulness, 4(4), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0134-1.

Gregory, G., & Chapman, C. (2013). One size doesn't fit all. Differentiated instructional strategies: One size doesn't fit all (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Corwin Publications.

Hjeltnes, A., Binder, P. E., Moltu, C., & Dundas, I. (2015). Facing the fear of failure: An explorative qualitative study of client experiences in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program for university students with academic evaluation anxiety. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 10(1), 27990. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v10.27990.

Hughes, B. M. (2005). Study, examinations, and stress: Blood pressure assessments in college students1. Educational Review, 57(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191042000274169.

Johnson, J. E. (2016). Effect of mindfulness training on interpretation exam performance in graduate students in interpreting. Doctoral dissertation, University of San Francisco. Retrieved from: https://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1310&context=diss

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2006). Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156.

Kerrigan, D., Chau, V., King, M., Holman, E., Joffe, A., & Sibinga, E. (2017). There is no performance, there is just this moment: The role of mindfulness instruction in promoting health and well-being among students at a highly-ranked university in the United States. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 22(4), 909–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587217719787.

Kim, J. H., Yang, H., & Schroeppel 2nd., S. (2013). A pilot study examining the effects of Kouk sun do on university students with anxiety symptoms. Stress and Health, 29(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2431.

Kindel, H. R. (2018). Toward Expert Clinicians: The Effects of Teaching Mindfulness in Physical Therapy Education. Robert Morris University.

Kitzrow, M. (2003). The mental health needs of today's college students: Challenges and recommendations. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 41(1), 167–181.

Lauricella, S. (2013). Mindfulness meditation with undergraduates in face-to-face and digital practice: A formative analysis. Mindfulness, 5(6), 682–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0222-x.

Lyzwinski, L. N., Caffery, L., Bambling, M., & Edirippulige, S. (2018). University Students’ Perspectives on Mindfulness and mHealth: A Qualitative Exploratory Study. American Journal of Health Education, 49(6), 341–353.

Malinowski, P. (2013). The Liverpool Mindfulness Model [web log comment]. Retrieved from http://meditation-research.org.uk/2013/02/the-liverpoolmindfulness-mode/

Morgan, B. M. (2016). Stress Management for College Students: An Experiential Multi-Modal Approach. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 12(3), 276–288.

National College Health Assessment Spring. (2015). 2015 reference group executive summary. American College of Health Association, https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_WEB_SPRING_2015_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf

Neuser, Ninfa J. (2010). Examining the factors of mindfulness: A confirmatory factor analysis of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire. Doctoral dissertation, Pacific University. Retrieved from: http://commons.pacificu.edu/spp/128

Oman, D., Shapiro, S. L., Thoresen, C. E., Plante, T. G., & Flinders, T. (2008). Meditation lowers stress and supports forgiveness among college students: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American College Health, 56(5), 569–578. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.56.5.569-578.

Parish, K. A. (2011). Quieting the cacophony of the mind: The role of mindfulness in adult learning. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 71(10-A), 3499.

Ramasubramanian, S. (2016). Mindfulness, stress coping and everyday resilience among emerging youth in a university setting: a mixed methods approach. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(3), 308–321.

Rapgay, L., & Bystrisky, A. (2009). Classical Mindfulness. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1172(1), 148–162.

Sattler, T. C. (2011) The effects of self-inquiry on mood states. Retrieved from http://undividedjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/The-Effects-of-Self-Inquiry-on-Mood-States-by-Tamra-Sattler.pdf

Schwind, J. K., McCay, E., Beanlands, H., Martin, L. S., Martin, J., & Binder, M. (2017). Mindfulness practice as a teaching-learning strategy in higher education: A qualitative exploratory pilot study. Nurse Education Today, 50(3), 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.12.017.

Shapiro, S. L., Schwartz, G. E., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21, 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018700829825.

Shonin, E., Gordon, W., & Griffiths, M. (2013). Meditation awareness training (MAT) for improved psychological well-being: A qualitative examination of participant experiences. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(3), 849–863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9679-0.

Solhaug, I., Eriksen, T. E., de Vibe, M., Haavind, H., Friborg, O., Sørlie, T., & Rosenvinge, J. H. (2016). Medical and psychology student’s experiences in learning mindfulness: Benefits, paradoxes, and pitfalls. Mindfulness, 7(4), 838–850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0521-0.

Stew, G. (2011). Mindfulness training for occupational therapy students. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(6), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802211X13074383957869.

The Condition of Education. (2014). National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2014083

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(45). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Watson, N. N., Black, A. R., & Hunter, C. D. (2016). African American Women’s Perceptions of Mindfulness Meditation Training and Gendered Race-Related Stress. Mindfulness, 7(5), 1034–1043.

White, L. (2014). Mindfulness in nursing: An evolutionary concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(2), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12182.

Yamada, K., & Victor, T. L. (2012). The impact of mindful awareness practices on college student health, well-being, and capacity for learning: A pilot study. Psychology Learning and Teaching, 11(2), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2012.11.2.139.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Because the current paper reports a systematic review of the literature, there was no direct contact with human subjects. Thus, we depend on the researchers whose work we have reviewed to be in compliance with ethical guidelines such as the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later addenda.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bamber, M.D., Schneider, J.K. College students’ perceptions of mindfulness-based interventions: A narrative review of the qualitative research. Curr Psychol 41, 667–680 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00592-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00592-4