Abstract

While many studies have examined the impact of forced migration on Venezuelan migrants in Latin America, to date scholars have not examined the effect of certain coping mechanisms, namely social support and emotion regulation. Using data from 386 Venezuelan migrants living in Peru (M = 20.22 years, SD = 1.33, 46.4% women), we investigated whether perceived social support from three different sources (family, friends, and significant other) correlated with emotion regulation strategies (cognitive reappraisal and suppression) while controlling for the type of cohabitation and time of residence. The results (1) confirmed the originally proposed internal structure of the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale and Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, showing reliability and validity even in a sample of migrants. Findings demonstrated that (2) perceived social support from family positively predicted cognitive reappraisal strategy when including friends and significant other as covariates; (3) Venezuelans who have resided longer in Peru compared to more recent migrants used cognitive reappraisal strategy at a higher rate despite perceiving low family social support; (4) Venezuelans who resided in Peru for a longer period of time reported higher suppression strategy use when having low significant other support; and (5) there were gender differences regarding cognitive reappraisal as a dependent variable. More specifically, in men, family was a better predictor than friend or significant other support, while among women, family and significant other had the biggest impact. These results demonstrate the importance of social support elements and time of residence on the healthy management of emotions under difficult circumstances, such as forced migration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

I. Introduction

Venezuelan migration has had one of the biggest social and economic impacts across Latin American societies in recent years. According to the United Nations Agency for Refugees, as of June 2019, there have been more than four million Venezuelan migrants and refugees around the world, making them one of the largest displaced populations in the world (UNHCR, 2018). Venezuela has faced major sociopolitical conflicts in the past decade, which combined with severe economic crisis has unleashed a humanitarian crisis (Gedan, 2017). Venezuelans have fled the country due to economic collapse, food shortages, lack of health services and medication, electricity shortages and blackouts, high unemployment, civil unrest, and political persecution, among other reasons (Castillo-Crasto & Reguant-Álvarez, 2017; John 2019; Mazuera-Arias et al. 2020; The Wilson Center, 2019).

Since 2000, there have been several stages in the Venezuelan migration process, which Vivas and Páez (2017) have categorized as three waves. The first wave, from 2000 to 2012, consisted of a moderate level of migration of middle-class, educated professionals to the USA and Europe, principally due to social and political change. The second wave occurred between 2012 and 2015 and stemmed from the country’s economic problems, such as a weakened gross domestic product (GDP), as well as government repression. This in turn generated a state of national emergency. During this second wave, migrants were not homogeneous as regards their economic and educational characteristics, and their destinations were primarily neighboring Latin American countries (e.g., Colombia, Panama, and the Dominican Republic). As of 2015, the humanitarian crisis became more severe as poverty, food and medication shortages, violence, and repression all increased, resulting in the subsequent departure of Venezuelans from every socioeconomic position. To date, this third wave has been characterized by the migration of people with few economic resources and whose objective is to live in South America, including Peru, the location of this study.

Peru is the second largest recipient of Venezuelan migrants after Colombia, with approximately 863,000 to 865,000 Venezuelan citizens (Migraciones, 2018). Most Venezuelans (78 to 88.6%) that reside in the capital, Lima (Juape, 2019; Response for Venezuelans, 2019), are primarily young people, (between 18 and 34) (75.1%), and the population leans slightly male (56.6%) (Blouin, 2019). While contextual and psychological measures of integration are pretty much non-existent in Peru, there are a few demographic indicators that could have implications for migrant adaptation. A large percentage of Venezuelans are high school graduates (37.5%), while 46.4% have technical or university studies. While the majority has not specified their occupation in Peru (82.5%), some state they work as vendors (1.6%), construction workers (1.1%), and housekeepers (1.1%). Others are simply identified as employees without stipulating any details (1.3%). The vast majority of Venezuelan migrants live in rental housing (87.8%). Some live with relatives (1.9%), in an association, with many people in the same place (0.7%), or on their own (0.2%). The most frequent health issues identified in the population are asthma (6.2%), high blood pressure (5.7%), and diabetes (2.8%) (71.8% did not respond as regards this issue) (Migraciones, 2018).

The vast number of migrants identified Peru as their final destination given socioeconomic conditions (43.7%), as a way to reunite with their family members (34.8%), or because of the ease of legal proceedings for migrants (12.5%) (Gestión, 2018). Peru’s economic conditions have improved greatly over the past 15 years, with an average of 6.5% GDP growth from 2003 and 2014, which became known in the region as the “Peruvian miracle” (Koechlin Costa et al., 2019), and a reduction in poverty from 30.8% in 2010 to 20.5% in 2018 (INEI, 2019). Informal employment is another factor that has attracted migrants in search of economic opportunities to the country. Nearly three-quarters of Peru’s workforce consists of informal workers, making incorporation into the labor force an easier feat for migrants than in more heavily regulated contexts (Koechlin Costa et al., 2019).

In addition to socioeconomic factors, Peru has implemented fairly open migration policies. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that Peru has had the highest number of refugee requests for Venezuelans worldwide, increasing by 400% since 2015 (UNHCR, 2018). Venezuelans initially were able to enter the country with only their national ID, and the government created a special regularization program to ensure that those entering the country were granted legal status. Temporary work permits were issued for nearly three-quarters of the migrant population, and while border policies are now more restrictive, migration policy has been one of the most open in the region and has allowed for a pathway to permanent residency (Seele et al., 2019).

When migratory processes occur, both the origin and recipient country are affected by the exit and entry of citizens. In the case of massive forced migrations, such as that from Venezuela, the arrival of foreigners with different cultures and customs necessitates the generation of new forms of coexistence, which may lead to increased political and economic pressures (Afonso & Devitt, 2016; Bove and Elia 2017), as well as social tension (Bellino and Dryden-Peterson, 2018; Wessendorf & Phillimore, 2018), which may manifest as rejection by the recipient society, or even in xenophobia (Crush & Ramachandran, 2010). Feelings of nationalism, demands to defend national security, fear of unemployment, and the association between existing social problems and migrant communities may be at the root of this rejection (Flores, 2018).

Migration is a complex, often traumatic experience that heightens individual vulnerability, induces high levels of stress and anxiety, and may even affect psychological well-being (Bhugra & Jones, 2001a, 2001b; Kuo, 2016; Virgincar et al., 2016). The stressors migrants face can be categorized as pre- and post-migration stressors, the former summarized mainly as fear and prior experience with conflict and trauma, and the latter as relocation, acculturative stress, loss of social status, and oppression by the host society, as well as physical and mental health issues (Yakushko et al., 2008). Migration implies individuals go through cultural transition (acculturation), which may involve changes to language, behavior, identity, and attitudes, all of which require coping mechanisms to deal with the immense amount of adjustment and pressure exerted by the host society (Berry, 1997; Bemak & Chung, 2008; Castro and Murray 2010; Kuo & Roysircar, 2006). As regards Venezuelans, given their economic precarity and labor conditions in Peru, these migrants are especially vulnerable to labor exploitation, discrimination, and even trafficking (Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, 2019; Seele et al., 2019).

While Peru has been lauded as an example for the region given its quick action in giving Venezuelan migrants legal status, this path to legal residency does not guarantee widespread protection of rights (Parent, 2017), and despite these government efforts, Venezuelan migrants face many of those difficulties outlined above. In terms of healthcare, they have less access to sexual and reproductive health services, which may result in unplanned pregnancies and abortions. Professionally, Venezuelans face legal barriers in the validation of degrees and professional and/or specialist qualifications. Socially, one in three Venezuelans has reported experiencing discrimination while residing in Peru (Mendoza & Miranda, 2019).

State-provided opportunities and resources may help with migrant integration into new societies. Yet other studies have found that improved social integration may also be due to specific personality and demographic factors (Australian Survey Research, 2011) such as education (Yuksel & Yuksel, 2018), occupation (Adedeji & Bullinger, 2019), housing (Yang et al., 2020), previous health conditions (Lin et al., 2017), and risk-taking and problem-solving skills (Nauriyal et al. 2020). Others found that individuals facing stressors may exhibit different physical and psychological reactions due to predispositions (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). As regards physical health, the healthy immigrant effect paradox (HIEP) suggests that migrants tend to have a better physical health status compared to native-born populations; however, this diminishes over time. Even though prior research have supported these findings as regards health issues, such as chronic diseases, obesity, and self-assessed health status (De Maio, 2010), other scholars have questioned these results due to non-significant differences in health status and inconsistent results in their analysis (Dunn and Dyck 2000; Laroche, 2000).

Scholars have also suggested that mental health is an important dynamic to explore as relating to migrant adaptation. Successful adaptation to a new and stressful environment may also be due to the use of psychological coping mechanisms. However, studies have found that migrants tend to have more mental health disorders (e.g., depression, PTSD) compared to the native-born population, but these tend to decrease over time of residence, especially when migrants cohabitate, interact, and enjoy support from people of the same status (De Maio, 2010; Hynie, 2018). In other words, this is the opposite effect of the HIEP, where, shortly after arrival, greater emotional symptoms exist compared to native populations and those migrants with a longer period of residence in the new country (Virgincar et al., 2016). Different coping strategies, such as avoidance, collective, and/or engagement coping, have been found to have different impacts on migrant mental health (Kuo et al., 2006). Other studies have found that “psychological adaptation is mainly a function of ethnic group variables (such as support networks)” (Ouarasse & van der Vijver, 2005, p. 268) and that migrants who are separated from their close social groups, such as family, are more likely to display mental health problems, such as depression (Bogic et al., 2015; Hynie, 2018).

In terms of mental health, while there have been proposals of public policies for the management of the mental and emotional health of migrants in Peru (Universidad del Pacífico, 2020), there are many current deficiencies in their application, principally due to service inequality at a national level, and the lack of programs specifically designed around population characteristics, such as gender, age, and origin group (Henao et al., 2016). As stated earlier, migration is usually associated with traumatic experiences, high levels of stress, anxiety, and depressive symptomatology (Bhugra & Jones, 2001a, 2001b; Virgincar et al., 2016). In the Peruvian context, the principal mental health disorders among migrants are those related to difficulties in regulating emotions, such as depression and anxiety, perhaps due to a lack of social support (Andina, 2019; Carroll et al., 2020).

Of particular importance for the mental and emotional health of migrants—and by extension, their general health and well-being—are social support and emotion regulation. Yet neither of these factors have been studied as coping mechanisms among the Venezuelan migrant population in Peru. We aim to fill this gap in the literature by examining their impact in this population. The following sections detail what social support and emotion regulation entail, before delving into their application in the current study.

Social Support

Social support, while it has been defined in many ways and has been assigned numerous functions, is the provision of appreciation, affection, and acceptance in the social group, and that this provision of support functions in two ways: integration and help. Cassel (1974) is often referred to as the initiator of the systematic review of the benefits of social support, while Caplan (1974) provided contributions as regards its functions, characterizing them as the feedback of validation and dominance over the environment that a person receives. Later, Cobb (1976) detailed the numerous benefits of social support.

Scholars have found that health and well-being can be positively impacted by social support (Harandi et al. 2017; Simich et al. 2005). However, this term lacks conceptual clarity and is often used as an umbrella term for other definitions and phenomena (Antoniou et al., 2009). Since social support is a multidimensional, context-sensitive variable that currently encompasses diverse elements, such as source, type, directionality, reciprocity, and visibility of support, its use may generate confusion. In certain cases, the difference between the perception and the sources of social support has been unclear (Antoniou et al., 2009).

Under this premise, we have defined social support as an exchange of resources perceived and/or expressed by a community, support networks, and interpersonal relationships, which provide emotional or instrumental support, both formally and informally for the management of stressful situations (Chavarría & Barra, 2014; Hombrados-Mendieta and Castro-Travé 2013; Záleská et al. 2014). Social support can also be considered a resource that helps in the management of emotion, as a way to reduce possible negativity from encountering difficulties in the social environment. However, this effect may depend on societal conditions, as well as the type of social support received in this environment (Simich et al., 2005). A greater availability of social support in a new context may significantly reduce the existing pressure on immigrants living in a bicultural environment (Safdar et al. 2009).

Social support is essential for our understanding of various psychological phenomena. It is significantly related to physical and mental health (Thoits, 1995), as the mere presence of people, considered a source of support (i.e. nuclear family), helps with individual emotion regulation (Green et al., 2002). In a systematic review of 85 quantitative studies of migrants around the world, a lack of social support, as well as other factors such as previous traumatic events, living alone or separated from family, and time spent in the new country, was associated with psychological distress or mental disorders. However, regarding the time of residence, results were not conclusive (Jurado et al., 2017).

Of all the instruments that exist to measure social support, most focus on the types of social support provided rather than on one’s perception of it (Ortiz & Baeza, 2011). However, the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale ([MPSSS], Zimet, et al., 1988) assesses perceived social support from three sources: family, friends, and significant other. Given its brevity and clarity as described by other authors (Navarro-Loli et al., 2019), we used this scale for the present investigation.

Zimet et al. (1988) proposed important definitional differences in their conceptualization of social support, which are reflected in the MPSSS. Different sources affect the perception of exchanges in social support, one of which is significant other (e.g., there is a special person who is around when I am in need). Two other sources are family (e.g., my family really tries to help me) and friends (e.g., I can count on my friends when things go wrong). Additional research has highlighted the benefits of perceptions of these types of social support in migration populations, with perceived family social support predicting happiness and well-being in immigrant women from Spain (Domínguez-Fuentes and Hombrados-Mendieta 2012) and perceived community social support predicting psychological well-being in migrants living in Finland (Jasinskaja-Lahti et al., 2006). Other studies have found that perceived social support enacts a buffering effect on depression and mental health in African immigrants based in Spain (Martínez-García et al. 2001) and also has been found to protect Korean migrants from acculturative stress in the USA (Lee et al., 2004).

Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation is a psychological strategy developed through constant human interaction, which promotes adequate responses according to context (Linehan, 1993). Emotion regulation has been defined as a process through which people exercise mastery over how and when they experience and express their emotions (Gross & John, 2003). It also implies the ability to initiate, maintain, modulate, or change the intensity, duration, or presence of emotion, adjusting to context and in order to achieve medium- and long-term social goals (Thompson, 1994).

There are a number of theoretical models related to emotion regulation. These theories describe emotion regulation as a process of human development, in which there are transactions between temperamental biological predispositions and social contexts (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Under this premise, Linehan (1993) developed the biosocial theory, in which certain biological components (referred to as emotional vulnerability), in addition to adverse contexts (referred to as invalidating environments), promote patterns of emotion dysregulation. Additional models based on sub-processes have been stipulated, such as that proposed by Gross (1998, 2001) which classified the phases of selection (focusing attention on one of two or more situations, those that generate some kind of emotional impact), modification of the situation (changing some aspect of the event due to the emotional impact it may produce), emotional unfolding (paying attention to only one aspect of the situation), cognitive change (selecting which potential emotional meaning is most connected to the situation), and response modulation (altering one or more of these response trends once they have been elicited).

Certain predictors related to social variables encourage emotion regulation processes, including social situations and interactions (Gross et al., 2006). An important factor is the relationship and support individuals develop with people in their environment (English et al. 2017). Also, while a person interacts with others, cognitive emotion regulation strategies are identified at higher rates compared to other processes, such as behavioral strategies to reduce high intensity emotions (Gross et al., 2006). In emotion regulation based on the Gross model (1998; 2001), there are two basic strategies. The first, cognitive reappraisal, consists of the attempt to reinterpret a situation that produces certain emotions in order to alter its meaning and subsequently change the emotional impact on the person (e.g., when I want to feel more positive emotion (such as joy or amusement), I change what I’m thinking about) (Gross & John, 2003). The use of cognitive reappraisal in individuals has been found to correlate with lower physiological reactions to stressors and fewer difficulties at the motor and emotional levels (Gross & John, 2003), demonstrating better personal functioning and well-being in general (Navarro et al., 2018). The second strategy, suppression, is defined as the attempt to hide, inhibit, and reduce behaviors that express the emotions experienced at a certain time (e.g., I control my emotions by not expressing them; see Gross & Levenson, 1993; Gross & John, 2003). Suppression in turn generates less social support, poorer coping skills, fewer interpersonal relationships, and lower satisfaction with life, low self-esteem and optimism for the future, and risk of depressive symptoms (John & Gross, 2004; Navarro et al., 2018; Sheldon et al., 1997).

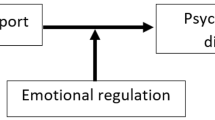

Cognitive and behavioral suppression are predictors of emotional distress and are considered to be counterproductive strategies, while cognitive reappraisal is not (Seligowski et al., 2014). In migrants residing in the Netherlands, suppression under certain contexts (e.g., positive and negative emotional manifestations during interactions with family and unknown people) was found to be a significant mediator of higher emotional suppression and low well-being (Stupar et al. 2014). In Australia, refugees with emotion regulation difficulties reported greater PTSD symptoms and emotion dysregulation strategies compared to emotionally regulated refugees (Specker & Nickerson, 2019). Emotion regulation can also be conceptualized as a transdiagnostic factor because of its associations and predictive ties to depression, PTSD symptoms, anxiety, and insomnia in Afghan refugees exposed to trauma (Koch et al. 2020). Considering these analyses, emotion regulation is an important variable to be analyzed in the migration and integration context.

II. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between perceived social support and emotion regulation strategies as coping mechanisms among the Venezuelan migrant population in Peru. To do so, we examined how perceived social support from different sources (family, friends, and significant other) correlated with emotion regulation strategies (cognitive reappraisal and suppression) in 386 Venezuelan migrants living in Peru in 2018. As previously discussed, these variables have been found to be highly associated with family dynamics and sociocultural factors present in migratory phenomena (Domínguez-Fuentes and Hombrados-Mendieta 2012; Gudiño et al., 2011). While studies related to issues of physical health, social, and demographic impact in this community have been carried out in Peru (Carroll et al., 2020; Mendoza & Miranda, 2019), psychological variables which are theoretically important for the study of migration have not yet been examined in depth in this population.Footnote 1 Given the importance of social support and its relationship to emotion regulation, we believe this study to be particularly important and contribute to understanding migratory phenomena both within and outside the Peruvian context.

Following prior findings, we thus formulated two hypotheses:

-

1.

We hypothesize that perceived social support (from family, friends, or a significant other) will positively correlate with cognitive reappraisal strategies.

-

2.

We hypothesize that perceived social support (from family, friends, or a significant other) will negatively correlate with suppression strategies.

III. Methodology

Study Design and Procedure

This study used non-probabilistic sampling through cross-sectional correlational design. These designs are usually used to examine if changes in one or more variables are related to changes in another variable at a particular point in time. Participants were first recruited while attending institutions in order to obtain certain residence permits and later via snowball sampling technique. Participants were asked to complete both psychometric tools (Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale [MPSSS] and Emotion Regulation Questionnaire [ERQ]) and a brief sociodemographic questionnaire. Given the location in which the study was conducted, the survey was necessarily brief, and additional variables and data could not be collected. Both tools were selected for this research given their low quantity of items as well as their use in different studies in Latin America, having been identified with adequate psychometric properties in different samples (Gabardo-Martins et al. 2017; Mosqueda Díaz et al. 2015; Pineda et al. 2018). The average duration for completing the questionnaire was about 15 to 20 min. Participation in the study was anonymous and voluntary and did not include monetary compensation. Informed written consent was given by participants.

Standard ethical practices were followed in the development of this human-subject research. All participants were informed of the objectives and purpose of the study; their participation was stressed as being completely voluntary and that participation could be withdrawn at any time during the study without any consequences. Complete confidentiality regarding participation and data access were also discussed. Participants were informed that the risks of participation were minor and mainly consisted of discomfort in answering any of the questions. Before participating and after a presentation of the research, individuals were asked to provide written informed consent. Given that the Faculty of Psychology of Universidad de Lima at the time this research was conducted did not have a research ethics board (which has since been developed in 2019), this study was able to achieve post-hoc institutional ethical approval.

Measures

Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MPSSS)

The MPSSS was created by Zimet et al. (1988), with the aim to assess the subjective or perceived evaluation of social support (mainly emotional components) using 12 items distributed in three oblique dimensions: family (items 3, 4, 8, 11; e.g., “I can talk about my problems with my family”), friends (items 6, 7, 9, 12; e.g., “I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows”), and significant other (items 1, 2, 5, 10; e.g., “There is a special person in my life who cares about my feelings”). Responses are on a Likert scale (1 = very strongly disagree, 7 = very strongly agree). Importantly, the MPSSS does not necessarily refer to physical proximity in the provision of social support—something that is important for research on migratory populations. Dimensions and final scores are obtained based on the average of the responses to the respective items. In the original version, validity evidence was obtained based on the internal structure using principal component analysis, using as evaluation criteria the eigenvalues and number of iterations, and by confirming the three-dimensionality and the structure of the initial proposal from the variable. Cronbach’s alpha indicated a good internal consistency for the dimensions of family, friends, and significant other (α = 0.88, 0.89, and 0.84 respectively).

In order to use this scale in the context of Peru, we followed previous studies and used the Spanish version (see Appendix), translated by the Pan-American Health Organization (2013). Given our knowledge that this scale has not previously been adapted for the Peruvian context, linguistic adaptations were carried out and subsequently reviewed by 5 judges, with highly significant Aiken’s content validity coefficients across all items (V = 1.00, p < 0.05).

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ)

The ERQ was originally created by Gross and John (2003) and was designed to evaluate two emotion regulation strategies: cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. The original scale consisted of 10 items, with a seven-point Likert response scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Cognitive reappraisal consisted of 6 items (items 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10; e.g., When I want to feel less negative emotion (such as sadness or anger), I change what I’m thinking about), while expressive suppression consisted of 4 items (items 2, 4, 6, 9; e.g., I control my emotions by not expressing them). Scores are obtained by calculating the mean responses. The Spanish version of the ERQ was translated as the Cuestionario de Auto-Regulación Emocional by Rodríguez-Carvajal and Moreno-Jiménez and Garrosa (2006), and a Peruvian linguistic adaptation was developed by Gargurevich and Matos (2010), which is the scale we used in this sample (see Appendix). Validity evidence based on the internal structure was obtained by principal component analysis, finding an adequate Kayser-Meyer-Olkin sample adequacy and a highly significant Barlett sphericity test (p < 0.001). Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis showed acceptable goodness of fit, ascertaining the bidimensionality structure of the test. Reliability and coefficients of internal consistency were identified using Cronbach’s alpha, revealing an acceptable fit for both cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression (α = 0.72 and 0.74, respectively).

Study Participants and Sample Size Calculation

Given the sociodemographic characteristics of the Venezuelan migrant population in Peru, primarily that 75% of migrants are young people aged between 18 to 34 years old (Blouin, 2019), the characteristics of our convenience sample attempted to reflect this reality of the migrant population, with ages ranging from 18 to 26 years old. The sample consisted of 386 Venezuelan migrants (M = 20.22 years, SD = 1.33; 53.6% men, 46.4% women) living in Lima, Peru. The vast majority had resided in the country between 0 and 6 months (50.3%), while the remaining had lived in Peru from 7 to 12 months (33.9%) or 13 to 24 months (15.8%). In addition, 40.7% lived with member(s) of their nuclear family, 35% lived with member(s) of their extended family or friends, 20.7% lived alone, and 3.6% shared housing with unknown persons, or of the same nationality.

A sensitivity power analysis was computed with G*Power 3.1.9.4: «Linear Multiple Regression: Fixed model, R2 deviation from 0 with 3 tested predictors» module. Given our sample size (N = 386), an alpha level of 5%, very high power (95%), the minimal detectable effect was small (f2 = 0.04) which ensured that even very modest effects could be detected with this sample.

Data Collection

Data was collected between April and November 2018 using non-probabilistic sampling through a cross-sectional correlational design. Convenience sampling was used given that the context and the nature of migration, as well as limited time and resources, did not allow for randomization. Participants were recruited through local institutions that serve migrants, primarily in the issuance of temporary residence permits, or through snowball sampling. Data was collected and administered both collectively and individually. Participants filled out written questionnaires in spaces close to those institutions. Another researcher, not involved with planning the research and collecting the data, examined the raw data and conducted the statistical analysis to minimize bias. There were no missing data.

Analysis

After examining basic descriptive statistics, we used confirmatory factor analysis to examine the factor structure of both scales, following theoretical and empirical evidence for both scales (Balzarotti et al., 2010; Matsumoto et al., 2008; Melka et al., 2011; Nakigudde et al., 2009. Using the lavaan package in R, we used a robust maximum likelihood estimator, fixing all latent variables to unity. We then extracted fit indices such as the Tukey-Lewis Index (TLI), an improved version of the Normed Fit Index that is not affected by sample size (Cangur & Ercan, 2015), that aimed to evaluate the distance between an independent and target model through Chi-square distribution. The bigger the TLI, the better the model fits the data, and cut-offs larger than 0.95 and 0.97 indicated an acceptable and excellent fit, respectively. We also used the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990) to compare a hypothesized and independent model, normed between 0 and 1 (cut-off generally falls around 0.90 with little to no influence from sample size, see Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996). We also used the Akaike (Akaike, 1973) and Bayesian Information Criteria (AIC/BIC) to evaluate the maximum likelihood function for the model (Schwarz, 1978), penalizing by parameters (2 k) and participants respectively (ln(n)k). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) indicated the fit of the model through the degree of misfit (generally lower than 0.05) and could be used both descriptively (e.g., sample estimates) and inferentially (with hypothesis testing and confidence intervals; Fan & Wang, 1998; Raykov, 1998). These fit statistics are presented in Table 3.

We also ensured our model fit the assumptions of multiple linear regression. The data displayed linearity, normality of the residuals, homogeneity of residual variance, and residual variance independence (see Figs. 1 and 2 in the Appendix). Also, the predictors (cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression) and residuals of the models were uncorrelated (p’s = 1). Finally, the variance inflation factor indicated indices of less than 2 which showed no sign of multicollinearity. We also examined the presence of potential outliers following the studentized deleted residual technique, in which a level greater than 4 are considered outliers (see McClelland, 2014). We systematically reported the adjusted R-squared as this penalizes for the inflation of parameters in a given model. All data was analyzed using RStudio version 1.2.5019.

To reduce hidden flexibility in statistical analysis (Chambers, 2019) and assessment bias and increase the accuracy and objectivity of our final results (Salkind, 2010), the researchers in this study that were involved in the analysis were not directly involved in planning/collecting the data. This procedure also prevents fishing (i.e., analyzing the data under different conditions, assumptions, or subgroups) which is known to inflate type I error rates (Kline, 2008). To evaluate the risk of selection bias, we compared sociodemographic data used by the Peruvian Migration Office (MIGRACIONES, 2018) to our sample. We found that age, sex, education levels, and professions were comparable between the general migrant population and our study sample. Since selection bias could mainly affect social indicators (e.g., perception of social support), we systematically ran linear regressions using these variables as covariates to control for said bias (Steiner et al., 2010).

IV. Results

Descriptive Statistics

All descriptive statistics (e.g., means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis) of the main variables are reported in Table 1. As can be seen, all variables were relatively well centered around the range mean (or slightly skewed) with the exception of family and significant other variables which were largely left-skewed (logging variables did not change the distribution shapes of these variables). This indicated that a vast majority of the sample perceived high levels of social support from family and significant other. The cognitive and expression factors of the ERQ scales (used as dependent variables in our model) displayed a slightly skewed distribution but with good graphical and quantile indexes. Migrants reported living in Peru for about 234.70 (SD = 178.51) days on average and tended to live with close relatives (e.g., family or spouse).

Correlation Matrix

When examining correlations between study variables (Table 2), we found that the strongest correlation was between family and significant other social support (r = 0.65, p < 0.001). Emotion regulation and social support were independent from the sociodemographic variables (p > 0.10) indicating these constructs to be orthogonal with each other. The cognitive reappraisal dimension was correlated with expression suppression (r = 0.18, p < 0.001), social support from family (r = 0.32, p < 0.001), friends (r = 0.22, p < 0.001), and significant other (r = 0.30, p < 0.001), whereas expressive suppression was negatively correlated with the significant other dimension of the MSPSS scale (r = − 0.14, p < 0.01). Finally, the time migrants spent in Peru and who they were living with did not correlate significantly with any of the other variables (p > 0.10).

Psychometric Properties

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the two scales used in our study (ERQ and MPSSS). CFA is a theory-driven analysis based on previous theoretical and empirical findings among the observed and unobserved variables. Following Schreiber et al. (2006), main fit indices are indicated in Table 3, and items’ factor loadings and communalities from the ERQ and MPSSS are reported in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. We used the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012) to run the CFA and used Maximum Likelihood non-biased estimators (ML) for robust standard errors. Component eigenvalues suggested 1 or 2 factors and 2 or 3 factors for the ERQ and MPSSS scales, respectively.

As can be seen in Table 3, the two-factor model for the ERQ displayed a systematically better fit in all indexes when compared to the single-factor model. Surprisingly, the two-factor model still presented some substantial misfit (RMSEA = 0.08 and very significant chi-square distribution) when compared to other recent validations (Spaapen et al., 2014). Good CFI/TLI fits when RMSEA/χ2 are high can sometimes be due to low correlations among variables (Muthen, 2010).

The CFA analysis for the MPSSS scale indicated a systematically better fit for the three-factor model when compared to the two-factor model. Again, inferential indexes revealed a relatively poor fit of the model (χ2 = 250.07, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.10) that could be due to low inter-item correlations. An alternative explanation has come from a theoretical debate about whether MPSSS really contains two (Stanley et al., 1998) or three dimensions (Zimet et al., 1988, 1990). However, previous CFAs (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000; Clara et al., 2003; Dahlem, Zimet, & Walker, 1991; Eker & Arkar, 1995; Kazarian & McCabe, 1991; Zimet et al., 1988) and psychometric indexes indicated that the three-factor model was clearly superior to the two-factor model in this sample.

Inferential Analysis

This study had two hypotheses which were tested using linear regression models. The first hypothesis expected to find a positive correlational relationship between perceived social support (from family, friends, or significant other) and cognitive reappraisal. The second hypothesis expected to find a negative correlation between these same types of social support and expressive suppression.

Cognitive Reappraisal

We used a linear regression model with cognitive reappraisal as the dependent variable, perception of family support as a predictor, and friends/significant other support as covariates. In line with Hypothesis 1, we found a positive correlation between social support and cognitive reappraisal. More specifically, we found that a higher perception of family support predicted better cognitive reappraisal [t(382) = 3.26, p = 0.001] than perception of significant other support [t(382) = 1.98, p = 0.048)] or support from friends [t(382) = 1.28, p = 0.20]; F(382) = 17.92, p < 0.001, R2adj = 0.12; see Table 4]. Controlling for age, sex, and cohabitation did not considerably affect the results of the models (p = 0.001, p = 0.059, and p = 0.18, respectively). Also, when examining only male participants, our results indicated that family support was also a better predictor of cognitive reappraisal [t(203) = 2.32, p = 0.02)] than friends or significant other’s support (p’s > 0.10). The subgroup analysis on women indicated a positive effect of family [t(175) = 2.08, p = 0.038)] and significant other support [t(175) = 2.17, p = 0.032)] on cognitive reappraisal but no effect of friends’ support (p = 0.44) Table 6.

Since perception of family social support correlated with the two other conditions, we ran two additional interactions to explore whether it affected the cognitive reappraisal outcome. Interactions are usually conducted to evaluate statistically significant differences across subgroups. Interactions can emerge when various factors are correlated, but sometimes they only appear when combined with each other in a regression term. While there was no interaction between perception of family and significant other support on our outcome while controlling for friends’ support [t(381) = 1.57, p = 0.12], there was a marginally positive interaction between perception of family and friends’ support on cognitive reappraisal [t(381) = 1.94, p = 0.05, R2adj = 0.12]. Another interaction emerged between perception of family support and time of residence in Peru on cognitive reappraisal (see Fig. 3 in the Appendix). Participants who perceived lower family support tended to report better cognitive reappraisal if they were in Peru for a longer time compared to newly arrived migrants [t(375) = − 2.04, p = 0.04, R2adj = 0.14 (with one outlier displaying a SDR > 4)], whereas there was no interaction of family support with type of cohabitation (p’s > 0.10, see Table 7). Given these findings, we can argue that Hypothesis 1 has found partial support.

Expressive Suppression

The second hypothesis expected to find a negative correlation between perception of social support and expressive suppression. In line with this hypothesis, we found that higher perception of support from a significant other predicted lower expressive suppression, but with a much weaker effect when compared to cognitive reappraisal [t(382) = − 1.98, p = 0.048, R2adj = 0.01; see Table 6]. Controlling for age, sex, or type of cohabitation did not significantly affect the results of the models. However, contrary to our hypothesis, we found that perceptions of support from family or friends were not correlated with expressive suppression (p > 0.60), nor did they interact (p > 0.78). A subgroup analysis on women indicated no effect of social support on participants’ expressive suppression (p’s > 0.10), whereas men were only marginally affected by friends’ support [t(203) = − 1.67, p = 0.098)] Table 8.

Again, given the possible differences in social support across subgroups, including time of residence, we decided to run an interaction analysis. An interaction emerged between perception of significant other support and time of residence in Peru on expressive suppression (see Fig. 4 in the Appendix). Participants who perceived lower significant other support tended to report higher expression suppression if they were in Peru for a longer time compared to more recently arrived migrants [t(376) = − 2.20, p = 0.028, R2adj = 0.01], whereas other interactions of different types of support with type of cohabitation were only marginally significant (p’s > 0.07, see Table 9). Given these findings, we can only partially confirm Hypothesis 2.

V. Discussion

Migration, especially when due to humanitarian and sociopolitical crisis, generates an impact on individuals, their primary group, and on the recipient society. Since Venezuelan migration to Peru is a relatively new phenomenon, journalists have focused primarily on analyzing its political consequences (El Tiempo, 2019; Response for Venezuelans, 2019; The Wilson Center, 2019). Some scholars have examined the political implications and reactions across the region (Acosta et al. 2019; Heredia & Battistessa, 2018; Seele et al., 2019), while other researchers have studied sociodemographic characteristics and the medical needs coming from this community (Bloun, 2019; Juape, 2019; Mendoza & Miranda, 2019), without considering other important variables based on the social determinants approach, such as health services and treatments, social and labor exclusion, and public policies related to mental health (WHO, 2020).

In order to analyze Venezuelan migration to Peru, it is important to identify differences and similarities between these two countries. While both are Latin American countries and thus share some cultural similarities, their history, geographic location, and other elements have led them to develop different sociocultural elements. In sociopolitical terms, in the past few decades, Venezuela has had more exposure to foreign migration compared to Peru (Defensoría del Pueblo 2020), which may explain why Venezuelans tend to be more accepting of other cultures, unlike the xenophobic treatment by some Peruvians towards the Venezuelan migrant population (Infobae, 2018; Mendoza & Miranda, 2019). Peru’s politics are characterized by a multiparty system, while Venezuela was dominated by essentially two political parties during the 1980s and only one today (Dietz & Myers, 2002). As regards similarities, social and family structures, perceptions of relationships, displays of affection, and support networks are fairly similar across both countries. In other words, they usually have the same social constructions in reference to how relationships should be structured across family, friendship, and partner relationships (Ariza and Oliveira 2007; Wrzus 2008). However, Venezuelans tend to be described as more talkative, relaxed, vain, and friendly, due to temperaments that are attributed to tropical Caribbean countries. On the other hand, Peruvians tend to be described as wary, individualistic, and less happy, perhaps due to associations with Andean culture. Migration between these countries has allowed for cultural exchanges, which is reflected in language, gastronomy, and customs. However, it has also led to discriminatory practices. In Peru, despite the fact that Caucasian and European migrants are generally more accepted over other Latino migrants, Venezuelan migrants have for the most part been well integrated into the local context.

Keeping these aspects in mind, it is important to note that the adaptation to a new political, economic, and social reality is of utmost importance for the successful integration of migrants into the new host country. While government policies that prioritize a legal path to residency, such as those implemented in Peru, may aid in individual assimilation, it is not an end-all solution. Migrants are vulnerable populations that may go through extreme stress and part of their successful integration may be due to their ability to psychologically adapt to these stressors. We therefore believe that it is incredibly relevant to research psychological variables, including those related to social and emotional factors in this population.

The aim of this study was to comprehend how certain social support variables were correlated with emotion regulation strategies in Venezuelan migrants who have experienced sociopolitical difficulties in their origin country, considering time of residence and cohabitation as intervening variables. In line with Hypothesis 1, we found that perceived family social support was more strongly related to cognitive reappraisal, compared to social support from friends and significant other. Cognitive reappraisal has been described as a healthy strategy since it helps people’s emotional management and well-being (Gross & John, 2003; Navarro et al., 2018). In order to develop such an important ability, a social support foundation is needed (Linehan, 1993; Thoits 1995), mainly from a primary group, such as family (Green et al., 2002; Thoits, 1995). Merely the presence of parents and their support are helpful factors that are related to reducing psychopathology, mainly posttraumatic stress disorder, and other issues, such as delinquency, substance abuse, and behavioral problems in young migrants (Gudiño et al., 2011). As a result, the positive relationship between perceived social support from the nuclear family and cognitive reappraisal in this study is comparable to these associations found in other studies of migrants from other countries (Domínguez-Fuentes and Hombrados-Mendieta 2012; Jurado et al., 2017).

The fact that perceived social support from one’s significant other and friends did not have a strong correlation with cognitive reappraisal causes us to speculate as to what could cause these conflicting statistical results. One idea is that the model that separates significant other from family may not represent the Latin American cultural perception of a primary group. The social interactions and the perception of support presented with family and a significant other (mainly known as a couple) are quite similar and generally could be integrated as one in the Latin American context. In other words, the couple is considered to be part of the family, since both provide significant emotional nurturing and care in the relationship, as well as economic support. For example, in Latin America, it is common for the man’s family and the couple to live together, sharing customs, routines, and perceptions (Ariza & Oliveira, 2007). On the other hand, friends are conceptualized as an external social support element and not a primary one, which could vary in emotional closeness, perceived reciprocity, and similarity, more so than in the other types of relationships (Wrzus, 2008). Since social support from friends is a different type than that of family (in which significant other may be included), the model including these two types of social support as independent variables that promote a healthy strategy of emotion regulation is well-founded culturally in Latin America.

Another explanation could be that the perceived social support coming from a significant other (translated as “persona especial” or special person in Spanish) as an emotional and filial relationship may stem from an understanding of this concept as a partner or an intimate friend. This explanation could also be plausible based on the age range of the sample (18–26 years). Generally in this phase of early adulthood, intimate and close relationships are formed with friends and individuals outside the family group. Given that this study takes place in a Latin American country, where close relationships with strong affective bonds are prevalent, these “special people” are quickly incorporated into the primary relationship environment and may be mentally represented as belonging to the family context (Ortega et al. 2018). This phenomenon could be accentuated by the fact that these young Venezuelans are far from their family group and have been forced to migrate given the difficult living conditions back home. Given that it is normal in this period of time for young adults to develop personal relationships with strong emotional ties outside the family context, such as best friend relationships or courtship, it may be possible that those surveyed in this study have conceived of these individuals as part of the family. This is common in Latin American cultures where non-family relationships satisfy emotional needs in similar ways, as well as becoming primary and intimate more quickly and easily (Blandón-Hincapié and López-Serna 2016; Ortega et al. 2018).

Another interesting finding from this study is the interaction between cognitive reappraisal and prolonged residency time when family social support was perceived as low. Time of residence seems to play an important role in the emotional adaptation of migrants to their new environment even when certain types of social support are not perceived, a finding consistent with prior studies (Millán-Franco et al. 2019). However, length of residence has been described in other investigations as a mental health risk factor (Choi et al. 2016; Honkaniemi et al. 2020). Another plausible explanation for the relationship between increased time in a country, low family social support, and cognitive reappraisal may be due to the greater likelihood of accessing government support programs. Or, it may be this relationship is due to the fact that migrants who arrived before 2018 had increased access to employment, government policies had fewer requirements, and housing was more available (Seele et al. 2019). Future studies should examine the link between government policies, socioeconomic conditions, and emotional adaptation in migrants.

Our second hypothesis examined the relationship between perceived social support and suppression. In line with this hypothesis, we found that lower levels of support from a significant other were related to a greater use of suppression strategies. Suppression has been found to be related to difficulties and negative outcomes on a psychological level (Seligowski et al., 2014), as well as regarding social components (Gross et al., 2006; John & Gross, 2004), including a lack of social support (Sheldon et al., 1997). We find a negative effect of social support from a significant other on suppression strategies in Venezuelan migrants, similarly to other studies (Seligowski et al., 2014). However, we did not find that perceived support from family or friends had a negative impact on suppression, leading us to only partly confirm Hypothesis 2. As reported by previous research (García Ramírez et al. 2002), the family is a fundamental source of support that contributes to the development of positive emotional regulatory strategies, both in male and female migrants. However, both in our study and in prior research, a significant other constitutes a more important source of social support for women than for men (Nauriyal et al. 2020; Soman et al. 2015).

When further exploring the relationship between significant other support and residency, we found that reductions in this support and longer residency encouraged the use of suppression as an emotion regulation strategy. Even though these results differ from those in the previous studies (Williams et al., 2018), others have found that time of residence is an ambiguous factor when it comes to migration (Jurado et al., 2017). Other studies report that the duration of residence in the receiving country can generate various consequences, including greater psychological discomfort among migrants from Sweden (Honkaniemi et al., 2020).

This relationship may also stem from health or other quality of life indicators. The healthy immigrant paradox has been a widely used proposal to formulate possible explanations when comparing migrant and native population health indicators. Many studies have identified that migrant populations have better health standards, including lower death rates and longer life expectancy. However, when considering certain diseases, this may vary over time, with a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and cognitive impairment in migrants (Markines and Gerst 2011; Markides & Rote, 2015). This phenomenon also occurs with regard to mental health (Honkaniemi et al., 2020), such as depression, anxiety, PTSD, emotional dysregulation, and psychological distress (Bhugra & Jones, 2001a, 2001b; Carroll et al., 2020; Honkaniemi et al., 2020; Kuo 2014; Specker & Nickerson, 2019; Virgincar et al., 2016). In this paradox, although residence time is considered an important element for health, as mentioned, there is conflicting evidence as regards mental health (Dunn and Dyck 2000; Laroche, 2000). A possible explanation for the relationship found in this study may be the quality of life in the host country. However, studies of places where the quality of life in the host country is not significantly better than the home country have not found a change in immigrants’ well-being (Jasinskaja-Lahti et al., 2006). Migrants may also face psychological, emotional, and social difficulties, as well as loss of health. This may be exacerbated when migrants decide to return to their home country, something that is becoming even more apparent in the COVID-19 pandemic (Jiménez Sandoval & Uzcátegui, 2020).

This study is not without limitations. Since migration is dynamic and constantly changing, these explanations are referential and exclusive to this non-probabilistic sample and period of time. While they make up the most common age of Venezuelan migrants in Peru (OIM, 2020), this study only surveyed young adults, who may indeed have their own unique psychological characteristics when compared to those in other stages of life. Unfortunately, given the difficulty of accessing and identifying the Venezuelan migrant population in Peru, this investigation was forced to rely on convenience sampling techniques. Also, based on those conditions, it was only plausible to consider a cross-sectional design to analyze the data. A longitudinal study would have been an interesting proposal, since it would have provided a better vision of the social and emotional processes through time in this community. Because of these methodological limitations, the findings of this study may not be representative of the Venezuelan migrant population in Peru.

It would have been useful to assess many other areas related to intrapersonal variables (e.g., personality and mental health), interpersonal variables (e.g., coping styles and social skills), and socioeconomic variables (e.g., educational level, employment status, place of residence, and monthly profit) of Venezuelan migrants in Peru, which would have increased the richness of the study. However, given limitations in terms of questionnaire duration and the difficulty of accessing to this sample, primarily because of their migratory status, we were unable to incorporate these variables in this study.

We also note that only a specific type of perceived emotional support was evaluated in this research. The MPSSS itself is limited to examining emotional support and does not make any explicit reference to physical proximity as a source of emotional support (see Appendix). By using this scale, we were unable to examine other forms of support, particularly those relying on physical proximity. Future research should examine other models of social support in the target population and perhaps even develop longitudinal studies to detect trends over time as well as the implementation of prevention and intervention strategies related to support networks and psychological coping mechanisms.

This was a first step in the examination of the relationship between perceived social support and emotion regulation strategies in Venezuelan migrants in Peru. Our principal finding is that perceived social support, above all stemming from one’s family, is an important factor in the migration process, and it influences the development of healthy emotion regulation strategies (cognitive reappraisal). We find that time of residence may promote better adaptation skills and regulation in migrants; however, these findings are preliminary. Additional studies should be conducted so as to verify how these relationships may also be related to the socioeconomic and political conditions in the receiving country.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

We are aware of one such study that examines the effects of the migration journey on Venezuelans’ mental health when choosing to migrate to Peru. Carroll et al. (2020) found that migration to Peru reduced the odds of anxiety among female migrants.

References

Acosta, D., Blouin, C., & Freier, L.F. (2019). La Emigración Venezolana: Respuestas Latinoamericanas (Working Paper No. 3). Madrid: Fundación Carolina.

Adedeji, A., & Bullinger, M. (2019). Subjective integration and quality of life of Sub-Saharan African migrants in Germany. Public Health, 174, 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.05.031

Afonso, A., & Devitt, C. (2016). Comparative political economy and international migration. Socio-Economic Review, 14(3), 591–613. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mww026

Antoniou, A.S., Cooper, C. L., Chrousos, G. P., Spielberger, C. D., & Eysenck, M. W. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of managerial behavior and occupational health. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Ariza, M., & Oliveira, O. (2007). Familias, pobreza y desigualdad social en Latinoamérica: Una mirada comparativa. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 22(1), 9–42. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/312/31222102.pdf

Australian Survey Research. (2011). Settlement outcomes of new arrivals. https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/settlement-services-subsite/files/settlement-outcomes-new-arrival.pdf

Bak-Klinel, A., Karatzias, T., Elliott, L., & Maclean, R. (2015). The determinants of well-being among international economic immigrants: A systematic literature review and Meta-Analysis. Applied Research Quality Life, 10, 161–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-013-9297-8

Balzarotti, S., John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2010). An Italian adaptation of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000009

Bhugra, D., & Jones, P. (2001a). Migration and mental illness. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 7, 216–223. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00246.x

Blouin, C. (Coord.). (2019). Estudio sobre el perfil socio económico de la población venezolana y sus comunidades de acogida: Una mirada hacia la inclusión. Lima: Instituto de Democracia y Derechos Humanos de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú y PADF

Bellino, M. J., & Dryden-Peterson, S. (2018). Inclusion and exclusion within a policy of national integration: Refugee education in Kenya’s Kakuma Refugee Camp. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 40(2), 222–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2018.1523707.

Bemak, F., & Chung, R. C.Y. (2008). Counseling and psychotherapy with refugees and migrants. In P. B. Pedersen, J. G. Draguns, W. J. Lonner, & J. E. Trimble (Eds.), Counseling across cultures (6th ed., pp. 307–324). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46, 5–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999497378467

Blandón-Hincapié, A.I., & López-Serna, L.M. (2016). Comprensiones sobre pareja en la actualidad: Jóvenes en busca de estabilidad. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 14(1). https://www.redalyc.org/jatsRepo/773/77344439034/html/index.html

Bogic, M., Njoku, A., & Priebe, S. (2015). Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15(29), 1–41.

Bove, V., & Elia, L. (2017). Migration, diversity, and economic growth. World Development, 89, 227–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.08.012

Bhugra, D., & Jones, P. (2001b). Migration and mental illness. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 7(3), 216–222.

Cabieses, B., Gálvez, P., & Ajraz, N. (2018). Migración internacional y salud: El aporte de las teorías sociales migratorias a las decisiones en salud pública. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública, 35(2), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2018.352.3102

Caplan, G. (1974). Support systems and community mental health: lectures on concept development. Behavioral Publications. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1974-26064-000

Carroll, H., Luzes, M., Freier, L. F., & Bird, M. D. (2020). The migration journey and mental health: Evidence from Venezuelan forced migration. SSM - Population Health, 10, 100551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100551

Cassel, J. (1974). Psychosocial Processes and “Stress”: Theoretical Formulation. International Journal of Health Services, 4(3), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.2190/wf7x-y1l0-bfkh-9qu2

Castillo-Crasto, T., & Reguant-Álvarez, M. (2017). Percepciones sobre la migración venezolana: Caudas, España como destino, expectativas de retorno. Migraciones, 41, 133–163. mig.i41.y2017.006

Castro, F. G., & Murray, K. E. (2010). Cultural adaptation and resilience: Controversies, issues, and emerging models. In J. W. Reich, A. J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 375–403). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Chambers, C. (2019). The seven deadly sins of psychology: A manifesto for reforming the culture of scientific practice. Princeton University Press.

Chavarría, M. P., & Barra, E. (2014). Satisfacción Vital en Adolescentes: Relación con la Autoeficacia y el Apoyo Social Percibido. Terapia Psicológica, 32(1), 41–46. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082014000100004

Choi, S., Kim, G., & Lee, S. (2016). Effects of nativity, length of residence, and county-level foreign-born density on mental health among older adults in the U.S. The Psychiatric quarterly, 87(4), 675–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-016-9418-2

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38(5), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003

Crush, J., & Ramachandran, S. (2010). Xenophobia, international migration and development. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 11(2), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452821003677327

Defensoría del Pueblo. (2020). Personas venezolanas en el Perú. Análisis de su situación antes y durante la crisis sanitaria generada por el COVID-19. https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/1481686/Informe-de-Adjunt%C3%ADa-N-002-2020-DP-ADHPD-Personas-Venezolanas-en-el-Per%C3%BA.pdf.pdf

Depresión y ansiedad están afectando a migrantes venezolanos en Perú. (2018). Andina. https://andina.pe/agencia/noticia-depresion-y-ansiedad-estan-afectando-a-migrantes-venezolanos-peru-709015.aspx

De Maio, F.G. (2010). Immigration as pathogenic: A systematic review of the health of immigrants to Canada. International Journal for Equity in Health, 9(27), 1–20. http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/9/1/27

Dietz, H., & Myers, D. (2002). El proceso de colapso de sistemas de partidos: Una comparación entre Perú y Venezuela. Cuadernos del Cendes, 50(50), 1–33. http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1012-25082002000200002

Domínguez-Fuentes, J. M., & Hombrados-Mendieta, I. (2012). Social support and happiness in immigrant women in Spain. Psychological Reports, 110(3), 977–990. https://doi.org/10.2466/17.02.20.21.PR0.110.3.977-990

Doocy, S., Page, K. R., de la Hoz, F., Speigel, P., & Beyrer, C. (2019). Venezuelan Migration and the border health crisis in Colombia and Brazil. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 7(3), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331502419860138

Dunn, J.R., & Dyck, I. (2000). Social determinants of health in Canada’s immigrant population: results from the National Population Health Survey. Social Science and Medicine, 51(11), 1573–1593. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11072880

English, T., Lee, I. A., John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2017). Emotion regulation strategy selection in daily life: The role of social context and goals. Motivation and Emotion, 41, 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-016-9597-z

Flores, G. (2018). Los discursos que alientan a la xenofobia en Ecuador. INREDH. http://www.inredh.org/index.php/archivo/derechoshumanos-ecuador/931-los-discursos-alientan-a-la-xenofobia-en-ecuador.

Gabardo-Martins, L., Ferreira, M., & Valentini, F. (2017). Propiedades Psicométricas da Escala Multidimensional de Suporte Social Percibido. Trends in Psychology, 25(4), 1873–1883. https://doi.org/10.9788/tp2017.4-18pt

García Ramírez, M., Martínez García, M. F., & Albar Marín, M. J. (2002). La elección de fuentes de apoyo social entre inmigrantes. Psicothema, 14(2), 369–374. http://www.psicothema.com/pdf/734.pdf

Gargurevich, R., & Matos, L. (2010). Propiedades psicométricas del cuestionario de autorregulación emocional adaptado para el Perú (ERQP). Revista Psicológica, 12, 192–215. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236220003_PROPIEDADES_PSICOMETRICAS_DEL_CUESTIONARIO_DE_AUTORREGULACION_EMOCIONAL_ADAPTADO_PARA_EL_PERU_ERQP

Gedan, B. N. (2017). Venezuelan Migration: Is the western hemisphere prepared for a refugee crisis? SAIS Review of International Affairs, 37(2), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2017.0027

Gestión. (2018). Mayoría de Venezolanos Llegan a Perú por Razones Económicas, según la OIM. https://gestion.pe/peru/politica/mayoria-venezolanos-llegan-peru-razones-economicas-segun-oim-229247-noticia/?ref=gesr

Green, G., Hayes, C., Dickinson, D., Whittaker, A., & Gilheany, B. (2002). The role and impact of social relationships upon well-being reported by mental health service users: A qualitative study. Journal of Mental Health, 11(5), 565–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230020023912

Gross, J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative view. Review of General Psychology, 2, 271–299.

Gross, J. J. (2001). Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 214–219.

Gross, J., & John, O. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362.

Gross, J., & Levenson, R. (1993). Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report and expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 970–986.

Gross, J. J., Richards, J. M., & John, O. P. (2006). Emotion regulation in everyday life. In D. K. Snyder, J. Simpson, & J. N. Hughes (Eds.), Emotion regulation in couples and families: Pathways to dysfunction and health (pp. 13–35). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Gudiño, O. M., Nadeem, E., Kataoka, S. H., & Lau, A. S. (2011). Relative impact of violence exposure and immigrant stressors on Latino youth psychopathology. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(3), 316–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20435

Harandi, T. F., Taghinasab, M. M., & Nayeri, T. D. (2017). The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electronic physician, 9(9), 5212–5222. https://doi.org/10.19082/5212

Heredia B., J.Y., & Battistessa, D. (2018). Nueva Realidad Migratoria Venezolana. Revista Electrónica Iberoamericana, 12(1), 1–31. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6833189

Honkaniemi, H., Juárez, S. P., Katikireddi, S. V., & Rostila, M. (2020). Psychological distress by age at migration and duration of residence in Sweden. Social science & medicine (1982), 250, 112869. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112869

Hombrados-Mendieta, I., & Castro-Travé, M. (2013). Apoyo social, clima social y percepción de conflictos en un contexto educativo intercultural. Anales De Psicología, 29(1), 108–122. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.1.123311

Hynie, M. (2018). The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: A critical review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(5), 297–303.

INEI (2019). Pobreza monetaria disminuyó en 1,2 puntos porcentuales durante el año 2018. Lima: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. https://www.inei.gob.pe/prensa/noticias/pobreza-monetaria-disminuyo-en-12-puntos-porcentuales-durante-el-ano-2018-11492/

Infobae. (2018). Venezolanos en Perú: lo bueno, lo malo y lo feo de dejar Caracas y llegar a Lima. https://www.infobae.com/america/america-latina/2018/07/27/venezolanos-en-peru-lo-bueno-lo-malo-y-lo-feo-de-dejar-caracas-y-llegar-a-lima/

International Organization for Migration [IOM]. (2017). World Migration Report 2018. https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/country/docs/china/r5_world_migration_report_2018_en.pdf

Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Liebkind, K., Jaakkola, M., & Reuter, A. (2006). Perceived discrimination, social support networks, and psychological well-being among three immigrant groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37, 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106286925

Jiménez Sandoval, C., & Uzcátegui, R. (2020). El Gobierno de Maduro debe dejar de Estigmatizar a quienes retornan por COVID-19. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/es/post-opinion/2020/04/22/el-gobierno-de-maduro-debe-dejar-de-estigmatizar-quienes-retornan-por-covid-19/

John, M. (2019). Venezuelan economic crisis: Crossing Latin American and Caribbean borders. Migration and Development, 8(3), 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2018.1502003

John, O., & Gross, J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72, 1301–1333.

Juape, M. (2019). ¿Dónde se ubican los ciudadanos venezolanos en Perú por domicilio y trabajo?. Gestión. https://gestion.pe/economia/empresas/ubican-ciudadanos-venezolanos-peru-domicilio-270124-noticia/?ref=gesr

Jurado, D., Alarcón, R. D., Martínez-Ortega, J. M., Mendieta-Marichal, Y., Gutiérrez-Rojas, L., & Gurpegui, M. (2017). Factores asociados a malestar psicológico o trastornos mentales comunes en poblaciones migrantes a lo largo del mundo. Revista De Psiquiatría y Salud Mental, 10(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2016.04.004

Kievit, R., Frankenhuis, W., Waldorp, L., & Borsboom, D. (2013). Simpson’s paradox in psychological science: a practical guide. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(513), 1–14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3740239/

Kline, R. B. (2008). Becoming a behavioral science researcher: A guide to producing research that matters. Guilford Press.

Koch, T., Liedl, A., & Ehring, T. (2020). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in Afghan refugees. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(3), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000489

Koechlin Costa, J., Solórzano Salleres, X., Larco Drouilly, G.L., & Fernández-Maldonado Mujica, E. (2019). Impacto de la Inmigración Venezolana en el Mercado Laboral en Tres Ciudades: Lima, Arequipa y Piura. Lima: Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. https://peru.iom.int/sites/default/files/Documentos/IMPACTOINM2019OIM.pdf

Kuo, B. C. H. (2014). Coping, acculturation, and psychological adaptation among migrants: A theoretical and empirical review and synthesis of the literature. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2013.843459

Kuo, B. C. H., & Roysircar, G. (2006). An exploratory study of cross-cultural adaptation of adolescent Taiwanese unaccompanied sojourners in Canada.Laroche, M. (2000). Health status and health services utilization of Canada’s immigrant and no-immigrant populations. Canadian Public Policy – Analyse de Politiques, 26(1), 51–75. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18271124.

Kuo, B. C. H., Roysircar, G., & Newby-Clark, I. R. (2006). Development of the cross-cultural coping scale: Collective, avoidance, and engagement strategies. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 39, 161–181.

Lazarus, R.S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing.

Lee, C. (2019). Venezuela’s public health crisis: National and regional implications. AMSA Journal of Global Health, 13(1), 30–36. http://ajgh.amsa.org.au/index.php/ajgh/article/view/40

Lee, J., Koeske, G. F., & Sales, E. (2004). Social support buffering acculturative stress: A study of mental health symptoms among Korean international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28, 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2004.08.005

Lin, Y., Zhang, Q., Chen, W., & Ling, L. (2017). The social income inequality, social integration and health status of internal migrants in China. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(139), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0640-9

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: The Guilford Press.

Markines, K. S., & Gerst, K. (2011). Immigration, aging, and health in the United States. In R.S. Settersen & E.M. Crimmins (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of aging (pp. 103-116). New York, NY: Springer.

Markides, K. S., & Rote, S. (2015). Immigrant health paradox. In Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Martínez-García, M.F., García-Ramírez, M., & Maya-Jariego, I. (2001). El efecto amortiguador del apoyo social sobre la depresión en un colectivo de inmigrantes. Psicothema, 13(4), 605–610. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=72713412

Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., Nakagawa, S., & Multinational study of cultural display rules. (2008). Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(6), 925–937. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.925

Mazuera‐Arias, R., Albornoz‐Arias, N., Cuberos, M.A., Vivas‐García, M., Morffe Peraza, M.A. (2020). Sociodemographic profiles and the causes of regular Venezuelan emigration. International Migration, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12693

Melka, S. E., Lancaster, S. L., Bryant, A. R., & Rodriguez, B. F. (2011). Confirmatory factor and measurement invariance analyses of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(12), 1283–1293. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20836

Mendoza, W., & Miranda, J.J. (2019). La inmigración venezolana en el Perú: Desafíos y oportunidades desde la perspectiva de la salud. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública, 36(3), 497–503. https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2019.363.4729

Millán-Franco, M., Gómez-Jacinto, L., Hombrados-Mendieta, I., González-Castro, F., & García-Cid, A. (2019). The effect of length of residence and geographical origin on the social inclusion of immigrants. Psychosocial Intervention, 28, 119–130. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a10

Mosqueda Díaz, Angélica, Mendoza Parra, Sara, Jofré Aravena, Viviane, & Barriga, Omar A. (2015). Validez y confiabilidad de una escala de apoyo social percibido en población adolescente. Enfermería Global, 14(39), 125–136. http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1695-61412015000300006&lng=es&tlng=es.