Abstract

This paper explores the extent of involvement of immigrant organizations with young 1.5 and 2nd generation immigrants by comparing two Latin American organizations: CSSP (The Centre for Spanish Speaking Peoples) in Canada and OLEI (Organizacion Latinoamericana en Israel) in Israel. By means of qualitative methodology, the findings indicate that while CSSP provides services to such young immigrants this is not the case with OLEI. This difference in the activities of these organizations can be explained by a theoretical schema composed of two key variables: characteristics of the immigrant population (motivation for immigration and the cultural heritage) and characteristics of the host country (immigration and integration policies and the society’s attitude towards immigrants). The paper demonstrates the usefulness of descriptive comparative case studies in unearthing antecedent variables that can help in building theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When immigrant groups settle in host countries, they invariably establish voluntary organizations to provide for their practical and cultural needs. Immigration studies have long recognized the presence of voluntary organizations established by immigrants, but these organizations have only recently become a topic of research (e.g., Owusu 2000; Moya 2005; Hung 2007; Guo and Guo 2011; Jurkova 2014). While most studies focus on immigrant organizations and the first generation of immigrant groups, little attention has been paid to the engagement of these organizations with successive younger generations, both children and youth. Furthermore, while the lives of second-generation immigrants have been considered by researchers from different perspectives (e.g., Dvir et al. 2015; Elias and Kemp 2010; Boyd 2009; Aparicio 2007; Louie 2001), researchers have not focused on the attention or supports given to the 1.5 and 2nd generations by immigrant organizations in the host countries. Accordingly, the purpose of this paper is to explore the extent of involvement of immigrant organizations with regard to the young 1.5 and 2nd generations from an organizational perspective.

In order to explore under what conditions an immigrant organization might develop services for the young, we have chosen to examine two organizations serving Latin American immigrants (one in Canada and one in Israel) that we found to differ on this topic. In Canada, there are more than 300,000 Latin American immigrants, the majority of whom live in Toronto. Among the many organizations that serve these immigrants, the largest is the Centre for Spanish Speaking Peoples known as CSSP. In Israel, the Organizacion Latinoamericana en Israel (Latin American Organization in Israel), known as OLEI, serves the 60,000 plus Latin American immigrants that live in this small country. Although both organizations were the first to serve the Latin American immigrant population in their respective countries, remain ethno-specific and were established in countries which encourage immigration in order to advance their population growth, there is one major difference between these two organizations: CSSP in Canada has chosen to mount programs for the 1.5 and 2nd generations while OLEI has not. The central argument advanced in this paper is that the involvement of immigrant organizations with the young 1.5 and 2nd generations is determined by the interactions between the specific characteristics of the immigrant population and characteristics of the host country.

Following a literature review on immigrant organizations, the paper presents the context of the host countries, Canada and Israel, including immigration, policies, and the Latin American communities. Then, the paper focuses on the Latin American organizations in both countries and analyzes their divergent attitudes towards the young generations. Following this analysis, we suggest a theoretical schema that could explain the differences in service provision.

Immigrant Organizations

Voluntary organizations among immigrants, such as churches, sports clubs, or schools, are a very frequent phenomenon which crosses religions, economic status, and types of immigration. These associations are created to address practical and cultural issues related to the settlement process in host countries (Moya 2005; Schrover and Vermeulen 2005, Babis, 2016a). They have different purposes and services, such as the so-called “initial welcome,” primary counseling for the immigrant, welfare and religious services, heritage preservation, and advocacy for rights (Dumont 2008; Camozzi 2011). Founded by new and long-term immigrants for their own communities, these organizations are, for the most part, non-profit organizations conforming to the laws governing nonprofits in their countries. As nonprofit organizations, they share the basic characteristics of the nonprofit sector: formal, private, non-distribution of profits, self-governing, and voluntary (Salamon and Anheier 1992). They can be ethno-specific or multicultural, funded by governments and/or private donors, but their main purpose is to help acclimatize new immigrants (e.g., Osuji 2013). Some view their role as integrative, and others focus on preserving culture through separation, and many follow a more integrative approach (BiParva 1994; Yükleyen and Yurdakul 2011). Some are also involved in political participation in the host country (De Graauw 2008), and/or transnational activities (Muñoz and Collazo 2014).

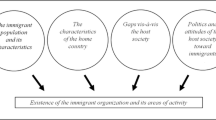

Although all immigrant organizations were founded as a consequence of immigration, their actual characteristics and activities are very diverse. This variety is the result of the combination of four main variables: (1) the attributes of the immigrant population, (2) the characteristics of the country of origin, (3) gaps vis-à-vis the host society, and (4) the attitudes and policies of the host society in relation to immigrants (Babis, 2016a).

The variety of immigrant organizations reflects a complex picture that makes it difficult to classify them into unequivocal categories. Nevertheless, there are some researchers who offer different categorizations for immigrant organizations. While Basch (1987) and Moya (2005) classify the organizations by their range of activities, Layton-Henry (1990) offers a typology of immigrant organizations according to their orientation towards the host country and/or the home country. Finally, Schrover and Vermeulen (2005) suggest that immigrant organizations can be one of two types: “defensive,” as a response to social rejection, or “offensive,” resulting from the immigrants’ choice to differentiate themselves from the rest of the population.

Immigration studies have frequently mentioned the presence of voluntary organizations established by immigrants, but these organizations have only recently become a topic of research. Some case studies, community studies, and comparative research studies focus on different dimensions and aspects of the phenomenon of immigrant organizations. These aspects include, among others, philanthropy (Marini 2013; Portes et al. 2007), voluntarism (Handi and Greenspan 2009), civil participation, incorporation/integration (Sardinha 2005; Pirkkalainena et al. 2013), service delivery (Jenkins and Sauber 1988; Korazim 1988), ethnic schools (Zhou and Kim 2006), transnational involvement (Marini 2013; Portes et al. 2007), and government nonprofit partnerships (Meinhard, Lo and Hyman, 2016). However, there has to date been no attention given to the extent of involvement of immigrant organizations with the young second generation.

Canada—Immigration, Policy, and the Latin American Community

Canada is often defined as a country of immigrants. In its earliest days, immigrants from France and Britain established settlements in the Atlantic Provinces and what is now Quebec and Ontario. Later, policies such as the Dominion Land Act were passed to encourage European immigration to settle the West in what are now the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia. This act gave newcomers 160 acres of land for free, provided they develop the land. Aside from the land grants and the provision of temporary housing until the land could be settled, immigrants were basically left to fend for themselves.

The 1970s saw a major shift in Canada’s approach to the integration of immigrants. First, the federal government became involved in the settlement process, mainly through partnerships with other levels of government and nonprofit service providing agencies, and second, by implementing a Multiculturalism Policy in 1971 to promote respect for cultural diversity and grant ethnic groups the right to preserve and develop their own cultures within Canadian society. In 1988, this policy was officially enacted by parliament as the Canadian Multiculturalism Act. It not only guaranteed equal opportunity for Canadians from all backgrounds and their right to preserve and share their unique cultural heritage but also emphasized the need to address the problems of race relations and the elimination of systemic inequalities (Mock 2002; Kunz and Sykes 2007; Hyman, Meinhard, & Shields 2011). Importantly, Canada remains the only country in the world to have an official Multiculturalism Act. Eschewing assimilation, the goal of the Act, and Canada’s official policy vis-a-vis newcomers, is no longer the total absorption of immigrants into a linguistic and cultural group by subordinating their own cultural identity, rather it is integration, where cultural identity is celebrated and harmonious relations are achieved through “unity in diversity” (Report of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism 1969, vol. 4, pp. 5–7).

Immigration policy in Canada has always been, and still is, fuelled by economic considerations. In the first instance, it was to populate the vast areas of uninhabited land in order to maintain the east-west contiguity of the country. More recently, it is to provide a workforce to fill the needs of an aging population with low natural birth rates. Immigration to Canada is governed by the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act passed in 2001 and last amended in 2014.

The criteria for immigration to Canada are selective, based on a point system of eligibility that covers language, education, experience, and age. Thus, in principle, applicants from any country, ethnic, and religious group have equal opportunities to immigrate to Canada. The focus is on encouraging the immigration of the most talented applicants. In addition to this, there is immigration for humanitarian reasons; this pertains to the acceptance of refugees and the family reunification program, which allows family members of new Canadians to come to Canada. After a certain length of residency, an immigrant can apply for Canadian citizenship. Gaining citizenship involves demonstrating proficiency in at least one of the official languages, and tested knowledge of Canada, its institutions, history and culture, and swearing an oath of allegiance.

The Latin American Community in Canada

Immigration to Canada from Latin America is a relatively recent phenomenon, harking back only to the 1970s, when large numbers of Latin Americans arrived as refugees, fleeing oppressive dictatorships in Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay. In the 1980s, they came from El Salvador and Guatemala as refugees fleeing military unrest and civil war (Ginieniewicz and McKenzie 2014, p. 267). Since the 1990s, Latin American immigrants came in search of economic prosperity (Simmons 1993), through the “skilled workers” immigration program (Veronis 2010). As of 2014, more than 266,000 immigrants from 20 Latin American countries (Armony 2014), representing a range of socioeconomic backgrounds (Veronis 2007), have come to Canada. According to data from the 2011 census, the ten main nationalities among Latin American immigrants are Colombian (61,300), Mexican (59,960), Salvadorian (38,260), Peruvian (22,115), Chilean (19,760), Brazilian (15,965), Cuban (13,105), Venezuelan (12,615), Guatemalan (12,480), and Ecuadorian (11,080) (Armony 2014, p. 11). While never the largest immigrant group, immigrants from Latin America consistently represented a significant proportion (circa 10%) of immigration.

Israel—Immigration, Policy, and the Latin American Community

Modern Israel is also a country of immigrants. The main impetus for immigration to Israel was Zionism, a movement which began at the end of the nineteenth century. Birthed in the throes of widespread European anti-semitism, the Zionist movement believed in the return of the Jewish people to their ancestral homeland as the only possible solution to persistent persecution. Based on this ideology, the Zionist movement encouraged immigration to Israel among Jewish communities worldwide. This immigration is called aliyah (going up), since it is considered to be not a regular immigration, but a “return to the homeland from the diaspora” (Semyonov and Lewin-Epstein 2003). The first wave of immigration was from the Russian Pale following the pogroms of the late nineteenth century, in which Jews were slaughtered by the thousands. Each successive wave of immigration helped serve to build the country. At the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, the “Law of Return” was legislated. According to this law, every Jew is eligible to immigrate to Israel and receive citizenship automatically (Shuval 1998). This law reflects the concept of Israel being the homeland, and if need be, a refuge for the Jews. Israeli immigration is based on Jewish parentage and/or grand parentage, and is considered part of the nation-building project of “ingathering of exiles” or returning diaspora (Kemp 2007).

In Israel’s early years, the perception of “diaspora ingathering” was characterized by a concerted effort to erase diasporic ethnic traditions, and by demanding acculturation to the image of the “new” Israeli. To attain this goal, immigrants were expected to abandon their culture from their emigrant countries and embrace the new Israeli culture. Basically, this meant that a melting pot approach was practiced with active measures to ensure assimilation (Shuval 1998). Critics of this absorption policy “began to talk about the need to respect the principle of pluralism, social, and cultural development, while maintaining the goal of gradually assimilating the immigrants and creating a shared Israeli culture” (Lissak 1999, p. 72). In the 90s, the melting pot concept became a negative reference point (“Errors’ of the 50s”) and a new multicultural perception provided legitimacy to some pluralism, allowing immigrant groups to preserve some cultural character (Leshem and Lissak 2001, p. 42).

Israeli immigration policy has been guided by three principles: (1) the “Open Door” principle by which every Jew has the right to immigrate to Israel; (2) the principle of “Automatic Citizenship” by which immediately upon immigration Jews receive citizenship, without any requirements of an exam or pledge of allegiance; and (3) the principle of all encompassing commitment by which all the arrangements both before and after arrival to Israel are provided by the state through the auspices of the Jewish Agency. In this vein, the immigration policy includes a wide range of services and support to new immigrants, such as initial housing, language, and economic supports, mostly provided by various government agencies. It also has various programs of acclimatization for different groups of immigrants, such as language acquisition programs, youth programs, academic programs, and family programs.

Although the State of Israel took and continues to take major responsibility for the integration of immigrants, many of its immigrant groups, dating back to the establishment of the State of Israel, created their own organizations for moral, social, and cultural support (Korazim 1988).

The Latin American Community in Israel

Immigration from Latin America to Israel began in the 1940s with about 100,000 Latin American immigrants recorded since 1948.Footnote 1 This immigration did not occur over a short period, but rather happened steadily over more than 70 years. These immigrants were mainly comprised of middle-class Jews, including families, academics, businessmen, professionals, and students. The main reasons for immigration were ideological, revolving around Zionist ideals or Jewish identity, and included, as a major factor, the concern for their children’s future as Jews. Other factors that contributed to Latin American immigration to Israel through the years were economic crises; anti-semitism; political persecutions during military regimes in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and Brazil; access to higher-quality education; and professional interests (Herman 1984; Sznajder and Roniger 2005; Roniger and Babis, 2008). Because of natural attrition and a percentage of returnees, the Latin American population in Israel stands today at around 60,000 people. This data includes only immigrants; the second generation is not included. The composition of the Latin American immigrant community is 64% from Argentina and the rest mainly from Mexico, Brazil, Uruguay, and Chile (source: Central Bureau of Statistics in Israel).

Profiles of the Latin American Immigrant Organizations in Israel and Canada

CSSP: Centre for Spanish Speaking Peoples

CSSP was founded in Toronto in 1973 with its main purpose being to help Spanish speakers overcome barriers based on language, race, age, and sexual orientation. It has 23 salaried workers and a varying number of volunteers, depending on need, to help with their services. As with many other immigrant organizations, about 80% of CSSP’s budget comes from government sources (in this case provincial and municipal governments), with the remainder coming from the United Way and other foundations. CSSP offers services to the Latin American population living in Toronto (approximately 99,000 people). Each year CSSP serves approximately 10,000 people seeking their assistance.

CSSP’s services include a Legal Clinic which provides legal services in the areas of immigration, refugee, and employment law among others. They also provide settlement services to immigrants for a smooth integration into the Canadian society. This contributes to the social development of the community, promoting self-awareness, self-sufficiency, and independence. This program offers help to immigrants in the process of obtaining Canadian citizenship, translating official documents, and providing social assistance, health care, employment, and professional search sources. The Women’s Program focuses on the issues of violence against women, and provides orientation and information about legal rights; escorting women to court; and crisis counseling. CSSP also offers an HIV/AIDS awareness and prevention program. Lastly, they have a Youth Program, which includes summer camp, a project against homophobia, arts programs such as videography, and a soccer league run by youth. They also publish a youth magazine which is called “Avenida Latina” (meaning Latin Avenue).

OLEI—Latin American Organization in Israel

OLEI was founded in 1948 with its main purpose being to help Latin American immigrants integrate into Israeli society. With its headquarters in Tel Aviv, the organization operates 23 local branches with a minimal staff of only 15 salaried employees, complemented with a network of nearly 1000 volunteers. Currently, OLEI has a country-wide membership of 6000. The organizational budget comes 9% from the Jewish Agency and Keren Ha-Yesod, with another 7% coming from municipalities and other governmental entities. The rest of OLEI’s revenue is self-generated from membership dues and rental income from their building.

OLEI’s services include personal assistance—such as welcome at the airport and help with translation and information and advice in different areas (e.g., education and housing). OLEI also organizes social and cultural activities, in the form of parties, Spanish-speaking tours around Israel, theater classes, and performances in Spanish. The organization also tries to help new immigrants to find a job, offers legal and psychological aid, and publishes national and local newsletters.

Notice that with respect to settlement services and social programs, CSSP and OLEI are very similar. However, while CSSP clearly sees providing support programming to 1.5 and 2nd generation youth as an important part of their mandate, OLEI does not. This difference in service provision is the focus of our exploration. Our research is driven by the question of understanding what forces lead to and support this difference in immigrant services for 1.5 and 2nd generation immigrants.

Methodology

This research is a comparative case analysis using qualitative methods (Wiewel and Hunter 1985). The data used for this analysis were initially collected for other studies by separate researchers in the two countries. In the case of CSSP, data was collected between 2009 and 2010 as part of a wide project on immigrant service organizations in Toronto which compared multicultural organizations with ethno-specific organizations. In the case of OLEI, data was collected as part of wide case study which explored various aspects of the phenomenon of immigrant organizations, such as dynamics of isolation and integration and historical development.

The data analyzed in this study was collected by means of interviews with leaders of both organizations. In the case of CSSP, interviews were in English while in OLEI were either in Spanish or Hebrew. In the case of OLEI, historical and documentary evidence was collected from the organization archive as well as in historical archives (Zionist Archive and the Israeli National Register for Non Profit Organizations). For the purpose of this comparison, additional data were collected later from the websites and Facebook pages of both organizations. Among all the data collected, the analysis focused on those pieces of data that were related to the attitudes of both organizations towards 1.5 and 2nd generations.

It must be acknowledged at the outset that methodologically this project did not start as a cross-country comparative research study. The case studies were conducted separately and with different purposes. Despite this limitation, we find the data sufficiently rich and informative for an initial exploration of the phenomenon. The data describes an important difference between two otherwise very similar organizations, and the subsequent conceptually grounded analyses suggest some interesting issues for further research.

The Involvement of CSSP and OLEI Regarding the 1.5 and 2nd Generations

CSSP and OLEI offer similar settlement services to the first generation of immigrants; however, one of the most significant differences that we found was with respect to their policies and perspectives regarding their services to the 1.5 and 2nd young generation immigrants: while CSSP provides services, OLEI does not. For CSSP, programs and activities for 2nd generation youth, in particular, are an important part of their mandate. For OLEI, this is definitely not the case. According to OLEI’s by-laws, for almost 40 years (until 1996), Latin American offspring were not allowed to be members of the organization since they were expected to have become integrated into Israeli society (Babis, 2016b). Although the by-laws have been changed, OLEI still does not provide services for the young 1.5 and 2nd generations. One reason for this difference is the discrepancy between patterns of integration experienced in the two countries. In IsraeI, we find a close overlap between the cultures and values of Latin American Jewish immigrants and the general Israeli host society. On the whole, Latin American immigrants are well integrated into Israeli society and it was never part of OLEI’s mandate, as an organization of a returning diaspora, to carry forward Latin American identity to the 2nd generation. As one of OLEI’s leaders expressed: “Our kids were born here and they are Israelis, they don’t need OLEI, they don’t have cultural problems”. A former president of OLEI even said:

“My kids coming to OLEI? What are they going to do there? It’s not natural, it is not good for the kids to come to OLEI (…) OLEI it’s good for the absorption of new immigrants, for adults, it gives them social life, they meet together and enjoy.”

Notice that this senior organizational member not only perceived no need to provide services to 2nd generation youth but in fact saw such provision as a negative influence—“it’s not good for the kids.” The implication here is that the ethnic specific organization has no mandate or mission to impart anything from its diasporic history to future generations. Whatever that history, it is as if it represents a limited, fleeting, sojourn. Indeed, an examination of some of the activities offered by OLEI (displayed in Fig. 1) show both the senior population targeted and the combination of socializing/assimilation in the form of meals and tours of Israel.

In this vein, one of the interviewees emphasized the role of OLEI as an organization among a returning diaspora, explaining that the “ideal” situation would be full and rapid assimilation into Israeli society even among Latin American adults:

At my age, over 50, it will be very hard to be integrated into Israeli society, therefore I look for a Latin American community environment for myself. My daughter is a different story (…) The purpose of OLEI is not to create a ghetto for the Latin American minority (…). The ideal would be that OLEI plays a role for the first 2… 3… 5… years until the immigrant is integrated into Israeli society, and after that bye bye, they would forget OLEI. This would be the ideal situation, but … an immigrant comes, who is above 60 years old, by the time he gets adapted after 5 years, at the age of 65–70, he will not start to become integrated [into Israeli society] and therefore a social framework should be offered to these people.

Again, we see here the over-arching goal to get over the need for the ethnic specific services and to say “bye bye and forget” the organization and perhaps the diaspora experience itself. According to this perception, only those who are too old to adapt and assimilate need the organization’s services.

In Canada, on the other hand, we find a declared multicultural policy in which each sub-culture is encouraged to celebrate their unique cultural heritage. Within the demands of Canada’s multi-cultural society, CSSP regards the nurture of Latin American identity and finding ways to positively transfer it to later generations an important part of its mandate. As one of the leaders of CSSP expressed:

“the message that it gives to people is that you don't have to lose your identity, while you’re in the process of adopting a new home. And I think that’s the message that tends to be quite central in all our events, because we always make an emphasis to people that this is their new home now, and so this is where they have to be invested emotionally and psychologically, but that doesn’t mean that you have to lose your identity. Why this so important for us, just to tie that with something else, two of the biggest issues right now affecting the Spanish speaking community in Toronto right now would be the high school drop-out rate is one of the largest one. (…) And according to all the studies that have been done, they revealed that there is quite an important central role that identity plays in the whole issue around cultural identity, because kids normally you find that kids usually you find the kids that are drop outs are the ones that tend to be the kids that either came here very early or were born here. (…) So, some of the connections that we’ve been able to make so far with these kids, there’s like a gap in which they fall because they call themselves Latino, but they don’t speak Spanish, and if they do, it’s with some struggle (…) “they consider themselves Latino. But at the same time, they don’t speak the language. And the knowledge of the culture, it’s a bit limited. Then on the other hand, they also consider themselves Canadian. But in school, they get reminded that they don’t fit in the stereotype of a Canadian, and also they don’t see themselves as represented in the history and institutions of the country. So there are those two sorts of issues at play, and they get caught in the middle”.

The interviewee makes clear that integration into Canadian society means yes there is a demand to adapt “but that doesn’t mean that you have to lose your identity.” The challenge with young immigrants, 1.5 or 2nd generation, is that they have no Latin American identity “to lose.” Their identity is being formed in the host country, and therefore, elements of Latin American culture, if desired, must be instilled by someone in Canada. Accordingly, CSSP’s aim is not only to preserve the Latin American culture where it exists but importantly to create and consolidate a strong, positive, ethnic identity among the youth, as a way to cope with the discrimination and alienation they sometimes have to deal with. Examples of events organized by CSSP (displayed in Fig. 2) show Latin American symbols (e.g., soccer) at the same time that they promote very positive images of Latin American strength, youth, merriment, community, and beauty.

Understanding the Differences

Our analysis suggests that the combination of two key variables can help to explain the different organizational attitude towards the younger generations: the characteristics of the immigrant population on the one hand and the characteristics of the host country on the other. Figure 3 (below) provides a basic schema of our observational interpretations.

Characteristics of the Immigrant Population

When analyzing the characteristics of Latin American immigrant populations in Canada and Israel, it was apparent that there are significant differences in the motivation for immigration. While immigration from Latin America to Canada is primarily driven by socioeconomic advancement or to escape political unrest (Canada being but one of many possible destinations), Jewish Latin American immigration to Israel occurs in the context of Zionist ideology, considered a returning diaspora coming back to the land of their ancestors (Semyonov and Lewin-Epstein 2003). Thus, while among OLEI’s objectives one can find the encouragement of “aliyah” (Jewish Immigration to Israel), the preservation of Latin American culture is not the objective of the organization. Moreover, OLEI does not promote the education of 1.5 and 2nd generations of immigrants into the language and culture of Latin America (Babis, 2016b). This is in contrast to CSSP, which operates to bestow the culture of origin to the next generation.

Another difference in the characteristics of the Latin American immigrant populations in Canada and Israel relates to cultural heritage. Latin American immigrants come to Canada with very deep roots, history, and indigenous heritage, sharing little with the destination population or place, neither language, nor history, nor culture, nor climate, nor food; the only common link might be shared Roman Catholic, religious values. Latin American immigrants in Israel, by contrast, do share a common heritage, history, and culture with the host country—the Jewish State—as they come from Jewish Latin American communities in which Jewish tradition is adhered to. The Latin American roots of these immigrants are not as deep as those of Latin American immigrants to Canada. They date back only to the late nineteenth to midtwentieth centuries, as a product of Jewish emigration mostly from Eastern European and Arabic countries. As a Jewish diaspora, these communities founded Jewish ethnic organizations for the maintenance and transmission of Jewish culture and identity to the second and subsequent generations (Avni 1991; Laikin Elkin 1985; Laikin Elkin 2003). Therefore, when arriving in Israel—the Jewish State—Jewish Latin American immigrants have a shared common heritage, history, and culture with the host country.

The consequences of these population differences can be found in examples of heritage programs run by both organizations. CSSP runs a youth focused program called El Tomate, which beyond environmentalism and urban farming issues, connects Latin American youth with the fact that the tomato is indigenous to Latin America. While at OLEI, for example, special ceremonies are held on Yom Hashoah (Holocaust Day), emphasizing their Jewish, diaspora roots, and history. However, unlike CSSP, this ceremony is not aimed at the 1.5 and 2nd young generations since children have similar ceremonies in the Israeli public schools.

The difference between the Latin American populations in both countries is well reflected in the organizational identity as expressed in the organizations’ logos: CSSP’s logo contains an indigenous motif of Latin American natives (see Fig. 4, CSSP’s logo), emphasizing a rooted Latin American identity. OLEI’s logo depicts a map of Latin America inside the Menorah—which is a Jewish motif and the national symbol of Israel (see Fig. 5, OLEI’s logo) emphasizing a diaspora (the map) within the “home land” (Menorah) of this returning diaspora.

CSSP’s logo. Source: www.spanishservices.org

OLEI’s logo. Source: www.olei.org.il

Characteristics of the Host Country

Policies towards diversity in the host countries shape the nature of the organizations as well. Canada’s multicultural policy not only accommodates but also seeks to maintain and celebrate cultural diversity. This in turn encourages sub-groups to develop and maintain positive communal values and practices as a way to maintain cultural continuity. It calls for actions and activities that transfer culture from first to later generations as occurs in CSSP. In Israel’s more assimilationist, melting-pot approach, diverse cultural continuity is more likely to be discouraged. As a returning diaspora, the focus of effort is to tap and re-invigorate shared historical culture rather than transpose diaspora elements. Little value is accorded to diaspora elements.

Beyond formal policy, the host society’s attitudes towards Latin American immigrants also influences the dynamics of the organizations. While Canada’s policy of inclusion and equality at the legislative level (e.g., the Multiculturalism Act) is promising, it by no means precludes discrimination and stigmatization. Indeed, the Latin American community, as a visible minority with low socio-economic status, has experienced both, perhaps augmented by negative media images from the USA. This is true not only of the first generation of immigrants but also their children. Recent statistics indicate a higher than average high school dropout rate (40% among Latin American immigrants vs. 23% overall). Latin American immigrants in Israel, by contrast, have been welcomed and assimilated, without obvious discrimination in both first and second generations. Indeed, they are often considered as an “invisible” community (Roniger and Jarochevsky 1992; Roniger and Babis, 2008; Siebzehner 2010; Raijman and Ophir 2014). Thus, it can be argued that while CSSP feels a necessity to offer support to the Latin American second generation as a way of dealing with their problems within Canadian society, this is not the case of OLEI.

Summary, Conclusions, and a Model for Future Studies

This study focused on a significant difference with regard to the services provided by immigrant organizations to 1.5 and 2nd generations. While CSSP devotes important resources to second generation young Latin Americans in Canada, OLEI in Israel does not. One reason for this lies in the different patterns of integration experienced in the two countries. In Israel, we find a close overlap between the cultures and values of Latin American Jewish immigrants and the general Israeli host society. On the whole, Latin American immigrants are well integrated into Israeli society and it was never part of OLEI’s mandate, as an organization of a returning diaspora, to carry forward Latin American identity to the second generation. In Canada, on the other hand, we find a declared multicultural policy in which each sub-culture is encouraged to celebrate their unique cultural heritage. Therefore, CSSP regards the nurturance of Latin American identity and finding ways to positively transfer it to later generations as part of its mandate. Their aim is not only to preserve the Latin American culture but also to consolidate a strong ethnic identity among the youth as a way to cope with the discrimination and alienation they sometimes have to deal with. Our study suggests that the combination of two key variables can help to understand these different practices: characteristics of the immigrant population (motivation for immigration and the cultural heritage) and characteristics of the host country (immigration and integration policies and the society’s attitude towards immigrants).

In order to offer a more comprehensive understanding of the role of immigrant organizations in the identity formation process of 1.5 and 2nd generation immigrants, we suggest in future research to combine the findings of this study with Berry’s theory (Berry, 1997; Berry 2006; Berry and Sabatier 2010). Based on Berry’s Acculturation Strategies (Berry, 1997; Berry 2006; Berry and Sabatier 2010), the figure below may offer the theoretical underpinnings for future studies. The model displays the interaction of three variables relevant to identity formation for the 1.5 and 2nd generation youth and the possible strategies that immigrant organizations might adopt. The three dimensions considered in this model are (a) cultural overlap between the immigrant’s culture of origin and the culture of the host society; (b) the focus of the host country in terms of what we call “cultural field,” i.e., whether the country recognizes and celebrates its cultural mosaic, or whether the country celebrates its dominant culture and believes in the concept of the “melting pot”; and finally, (c) experiences of discrimination felt by the cultural group (Fig. 6).Footnote 2

It will be interesting for future research to explore the perspectives and experiences of the 1.5 and 2nd generations regarding immigrant organizations. With the vast migrations that we are witnessing today, migrations that involve the meeting of highly different cultures, understanding the role of immigrant organizations towards 1.5 and 2nd generations from different perspectives may play an important role in planning programs to ease the issues facing culturally different second generation youth. There is an important mediating role for immigrant organizations to play in helping the 1.5 and 2nd generation children navigate through both their home traditions and their new surroundings. However these programs cannot be universal, since they have to take into account historical and present dimensions of every specific immigrant group and the specific national context of their immigration.

Notes

Although the model is presented as a 2 × 2 × 2 design, in truth, there are two empty cells, i.e., theoretical situations which are highly unlikely to occur.

References

Aparicio, R. (2007). The integration of the second and 1.5 generations of Moroccan, Dominican and Peruvian origin in Madrid and Barcelona. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33, 1169–1193.

Armony, V. (2014). Latin American communities in Canada: Trends in diversity and integration. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 46(3), 7–34.

Avni, H. (1991). Argentina and the Jews: A History of Jewish immigration. Tuscalosa: University Alabama Press.

Babis, D. (2016a). Understanding Diversity in the Phenomenon of Immigrant Organizations: A Comprehensive Framework. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(2), 355–369.

Babis, D. (2016b). The Paradox of Integration and Isolation within Immigrant Organizations: The Case of a Latin American Association in Israel. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(13), 2226–2243.

Basch, L. (1987). The Vincentians and Grenadians: The role of voluntary associations in immigrant adaptation to new York City. In N. Foner (Ed.), New immigrants in New York (pp. 95–159). New York: Columbia University Press.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46, 5–34.

Berry, J. W. (2006). Mutual attitudes among immigrants and ethnocultural groups in Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(6), 719–734.

Berry, J. W., & Sabatier, C. (2010). Acculturation, discrimination and adaptation among 2nd generations immigrant youth in Montreal and Paris. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34, 191–207.

BiParva, E. (1994). Ethnic organizations: Integration and assimilation vs. segregation and cultural preservation with specific reference to the Iranians in the Washington, DC metropolitan area. Journal of Third World Studies, 11, 369–404.

Boyd, M. (2009). Social origins and the educational and occupational achievements of the 1.5 and second generations. Canadian Review of Sociology, 46, 339–369.

Camozzi, I. (2011). Migrants' associations and their attempts to gain recognition: The case of Milan. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 11(3), 468–491.

De Graauw, E. (2008). Nonprofit organizations: Agents of immigrant political incorporation in urban America. In S. K. Ramakrishnan & I. Bloemraad (Eds.), Civic hopes and political realities: Immigrants, community organizations and political engagement (pp. 323–350). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Dumont, A. (2008). Representing voiceless migrants: Moroccan political transnationalism and Moroccan migrants’ organizations in France. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(4), 792–811.

Dvir, N., Aloni, N., & Harari, D. (2015). The dialectics of assimilation and multiculturalism: The case of children of refugees and migrant workers in the Bialik-Rogozin school, Tel Aviv. Compare - a Journal of Comparative and International Education, 45(4), 568–588.

Elias, N., & Kemp, A. (2010). The new second generation: Non-Jewish olim, black Jews and children of migrant workers in Israel. Israel Studies, 15(1), 73–94.

Ginieniewicz, J., & McKenzie, K. (2014). Mental health of Latin Americans in Canada: A literature review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60(3), 263–273.

Guo, S., & Guo, Y. (2011). Multiculturalism, ethnicity and minority rights: The complexity and paradox of ethnic organizations in Canada. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 43(1), 59–80.

Handi, F., & Greenspan, I. (2009). Immigrant volunteering - a stepping stone to integration? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(6), 956–982.

Herman, D. L. (1984). The Latin-American Community of Israel. Praeger Publishers.

Hung, C. K. R. (2007). Immigrant nonprofit organizations in US metropolitan areas. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(4), 707–729.

Hyman, I., Meinhard, A., & Shields, J. (2011). The role of multiculturalism policy in addressing social inclusion processes in Canada. Edmonton: Canadian Multicultural Educational Foundation.

Jenkins, S., & Sauber, M. (1988). Ethnic associations in New York and services to immigrants. In S. Jenkins (Ed.), Ethnic associations and the welfare state: Service to immigrants in five countries (pp. 21–105). New York: Columbia Press.

Jurkova, S. (2014). The role of ethno-cultural organizations in immigrant integration: A case study of the Bulgarian Society in Western Canada. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 46(1), 23–44.

Kemp, A. (2007). Managing migration, reprioritizing national citizenship: Undocumented migrant workers' children and policy reforms in Israel. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 8(2), 663–692.

Korazim, J. (1988). Immigrant associations in Israel. In S. Jenkins (Ed.), Ethnic associations and the welfare state: Service to immigrants in five countries (pp. 155–202). New York: Columbia Press.

Kunz, J.L., & Sykes, S. (2007). From mosaic to harmony: Multicultural Canada in the 21st 29 century: Results of regional roundtables. Policy Research Institute. Report to Government of Canada.

Laikin Elkin, J.(1985). Latin American Jewry today. American Jewish Year Book, pp. 3–49.

Laikin Elkin, J. (2003). Latin and Jewish: The Jews of Argentina in the Twenty-First Century. In S. Encel & L. Stein (Eds.), Continuity, Commitment and Survival – Jewish Communities in the Diaspora (pp. 149–171). Wesport: Prager Publishers.

Layton-Henry, Z. (1990). Immigrant associations. In Z. Layton-Henry (Ed.), Political rights of migrant workers in Western Europe (pp. 94–112). London: Sage.

Leshem, E., & Lissak, M. (2001). The social and cultural consolidation of the Russian community in Israel. In M. Lissak & E. Leshem (Eds.), From Russia to Israel identity and culture in transition (pp. 27–76). Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hemeuhad (In Hebrew).

Lissak, M. (1999). The mass immigration in the fifties: The failure of the melting pot policy. Jerusalem: The Bialik Institute (In Hebrew).

Louie, V. (2001). Parents' aspirations and investment: The role of social class in the educational experiences of 1.5 and second- generation Chinese Americans. Harvard Educational Review, 71, 438–474.

Marini, F. (2013). Immigrants and transnational engagement in the diaspora: Ghanaian associations in Italy and the UK. African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal, 6(2), 131–144.

Meinhard, A., Lo, L., & Hyman, I. (2016). Cross-sector partnerships in the provision of services to new immigrants in Canada. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership, & Governance, 40, 281–296.

Mock, K. (2002). Redefining multiculturalism. Adapted from a presentation at the University of Victoria conference Changing Multicultural Identities and published by the University of Victoria in 2002 on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of the Multiculturalism Policy.

Moya, J. C. (2005). Immigrants and associations: A global and historical perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31(5), 833–864.

Muñoz, J. A., & Collazo, J. L. (2014). Looking out for Paisanos: Latino hometown associations as transnational advocacy networks. Migration and Development, (ahead-of-print), 1–12.

Osuji, C. (2013). Building power for “Noncitizen citizenship”. A case study of the multi-ethnic immigrant workers organizing network. M, Ruth, J. Bloom, & V. Narro (Eds.), Working for justice: the LA model of organizing and advocacy, 89–108.

Owusu, T. Y. (2000). The role of Ghanaian immigrant associations in Toronto, Canada. International Migration Review, 34(4), 1155–1181.

Pirkkalainena, P., Mezzettib, P., & Guglielmoc, M. (2013). Somali Associations' trajectories in Italy and Finland: Leaders building trust and finding legitimization. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39(8), 1261–1279.

Portes, A., Escobar, C., & Walton Radford, A. (2007). Immigrant transnational organizations and development: A comparative study. International Migration Review, 41(1), 242–281.

Raijman, R., & Ophir, A. (2014). The economic integration of Latin Americans in Israel. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 46(3), 77–102.

Raijman, R., Schamrnah-Gesser, S., & Kemp, A. (2003). International migration, domestic and care work: Undocumented Latin migrants in Israel. Gender and Society, 17(5), 727–749.

Roniger, L., & Babis, D. (2008). Latin American Israelis: The Collective Identity of an Invisible Community. In J. Bokser Liwerant, E. Ben-Rafael, Y. Gorny, and R. Rein (Eds.) Identities in an Era of Globalization and Multiculturalism: Latin America the Jewish World (pp. 297–320). Leiden: Brill.

Roniger, L., & Jarochevsky, G. (1992). Los latinoamericanos de Israel: La Comunidad Invisible. Reflejos, 1(1), 39–49.

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1992). In search of the non-profit sector. I: The question of definitions. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 3(2), 125–151.

Sardinha, J.M.S. (2005). Cape Verdean Associations in the Metropolitan Area of Lisbon: their role in integration. Sussex Migration Working Paper 26. In: http://time.dufe.edu.cn/wencong/sussex/mwp26.pdf

Schammah-Gesser, S., Raijman, R., Kemp, A., & Reznik, J. (2000). ‘Making it’ in Israel? Non-Jewish Latino undocumented migrant Workers in the Holy Land. Estudios lnterdisciplinarios de America Latina y el Caribe II, 2, 113–136.

Schrover, M., & Vermeulen, F. (2005). Immigrant organisations. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31(5), 823–832.

Semyonov, M., & Lewin-Epstein, N. (2003). Immigration and ethnicity in Israel: Returning diaspora and nation-building. In M. Rainer & O. Rainer (Eds.), Diasporas and ethnic migrants: Germany, Israel, and post-soviet successor states in comparative perspective (pp. 327–337). London: Frank Cass.

Shuval, J. T. (1998). Migration to Israel: The mythology of “uniqueness”. International Migration, 36(1), 3–26.

Siebzehner, B. (2010). Un imaginario inmigratorio: ideología y pragmatismo entre los latinoamericanos en Israel. In: Avni H, Bokser Liwerant J, Della Pergola S, Bejerano M, and Senkman, L. (eds.) Pertenencia y alteridad. Judíos en América Latina: cuarenta años de cambio. Madrid: Ed. Iberoamericana Editorial Vervuert, 389–416.

Simmons, A. B. (1993). Latin American migration to Canada: New linkages in the hemispheric migration and refugee flow system. International Journal, 48, 282–309.

Sznajder, M., & Roniger, L. (2005). From Argentina to Israel: Escape, evacuation and exile. Journal of Latin American Studies, 37(02), 351–377.

Veronis, L. (2007). Strategic spatial essentialism: Latin Americans' real and imagined geographies of belonging in Toronto. Social & Cultural Geography, 8(3), 455–473.

Veronis, L. (2010). Immigrant participation in the transnational era: Latin Americans' experiences with collective Organising in Toronto. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 11(2), 173–192.

Wiewel, W., & Hunter, G. (1985). The interorganizational network as a resource: A comparative case study on organizational genesis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30(4), 482–496.

Yükleyen, A., & Yurdakul, G. (2011). Islamic activism and immigrant integration: Turkish organizations in Germany. Immigrants & Minorities, 29(01), 64–85.

Zhou, M., & Kim, S. S. (2006). Community forces, social capital, and educational achievement: The case of supplementary education in the Chinese and Korean immigrant communities. Harvard Educational Review, 76, 1–29.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Babis, D., Meinhard, A.G. & Berger, I.E. Exploring Involvement of Immigrant Organizations With the Young 1.5 and 2nd Generations: Latin American Associations in Canada and Israel. Int. Migration & Integration 20, 479–495 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-018-0617-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-018-0617-6