Abstract

This qualitative study aimed to explore views (and related experiences) of healthcare providers regarding immigration and its relation to psychosis, such as schizophrenia, particularly to identify support needs and challenges of immigrants with psychosis and related challenges and enablers of their mental health service providers. The objectives of this study were to identify (1) barriers and enablers of mental health and other services for Canadian immigrants with psychosis and (2) barriers and enablers for their mental health service providers. The study used a phenomenological approach to elicit views of 12 mental healthcare providers with experience in providing mental healthcare to immigrants with psychosis. Semi-structured individual interview data obtained were coded and thematically analyzed. Six themes in relation to the experience of service provision to immigrants with psychosis were found: the immigration process, service availability and accessibility, social determinants of health, cultural context, psychosocial stressors, and enablers and facilitators of recovery. The most prominent challenges/barriers were related to cultural context, language, social and health services, and support. Most mental healthcare providers believed that immigration process precipitates the first episode of psychosis in a majority of immigrants and that psychosis was undetected/non-present when in the country of origin. This study demonstrated system challenges and related opportunities for service provision for immigrants with psychosis. We identified important areas for intervention to reduce disparities for immigrants with psychosis in their use of social and health services. Future directions for research in relation to immigration of people with psychosis are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Various publications have consistently shown a strong association between the prevalence and incidence of psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and immigration (Bhugra 2000; Coid et al. 2008; Leff 2006), along with a considerable risk for disparity related to both ethnic minority groups and host society contexts (Seeman 2010; Bourque et al. 2010). A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies (Cantoor-Graae and Selten 2005) reported that the mean weighted relative risk for developing schizophrenia was 2.7 and 4.5 times higher than in the general population among first-generation and second-generation immigrants, respectively; it also showed significant differential risk patterns across subgroups (black vs white and developing vs developed countries), suggesting a role for psychosocial adversity in the etiology or at least triggering of schizophrenia. This is true in particular for psychosis in some immigrant groups such as African Caribbean immigrants to the UK (Leff 2006; Bourque et al. 2010). In contrast to findings from the UK and Europe, immigration to Canada appears to confer a lower risk of mental health problems, particularly mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders (Kennedy et al. 2006; Kirkbride and Hollander 2015). A study conducted in the province of Ontario (Anderson et al. 2015) demonstrated significantly lower incidence rates of psychotic disorders among immigrants from East Asia and most parts of Europe and higher incidence rates for immigrants from East Africa and South Asia, relative to the general population.

Vulnerable individuals and populations are prone to social injustice, which is an ongoing ethical challenge such as poverty, discrimination, subordination, lack of social support, political marginalization, disenfranchisement, and denial of human rights (Prior and Harfield 2012). Clinical vulnerability, such as psychosis (hallucinations and thought disorder), and social vulnerability, such as immigration, respectively, increase the risk of social injustice towards people experiencing them (Prior and Harfield 2012). Immigration may be accompanied by traumatic or derailing events—before, during, or after dislocation—that lead to serious psychological distress of clinical proportions (Desjarlais et al. 1995). The post-migration factors seem to play a more important role than pre-migration factors, and the increased risk of schizophrenia and related disorders among immigrants is mediated by their new social context (Borque et al. 2010). More generally, higher rates of sustained mental health problems (Roth et al. 2006) and diagnosable psychiatric disorders are observed among immigrants in comparison to similar cohorts remaining in their countries of origin (Veling and Susser 2011).

The increased risk for developing psychotic disorders among immigrants may be partly explained by psychosocial stressors such as social defeat, social disadvantage, isolation, racism, greater exposure to social adversity, genetic vulnerability, stigma related to differences in physical appearance and culture dissimilarity, separation from parents in childhood and family dysfunction, and low economic status (Morgan et al. 2008; Morgan and Hutchinson 2010; Hjern et al. 2004; Mallet et al. 2002; Patino et al. 2005; Selten and Cantor-Graae 2005; Smith et al. 2006; Weiser et al. 2008). Research has shown that psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia are often triggered by stress (Rudnick and Lundeberg 2012), particularly during periods of economic challenge (Smith et al. 2006), which immigrants often face.

Although Canadian immigration rates are high, research that systematically explores the issues related to immigration to Canada in relation to psychosis has not been published much, if at all (Whitley et al. 2006), and qualitative studies exploring this are scant (Menzes et al. 2011). A study which reviewed over 40 years of North American literature with respect to the role of social factors in the etiology of psychosis, including schizophrenia, confirmed this dearth of Canadian literature, while noting many such publications from Europe (Coid et al. 2008). As well, in general, there are no published studies reporting views of mental healthcare providers who work with immigrants with psychosis (Lauderdale et al. 2006; Wamala et al. 2007). Hence, to address both these gaps in scientific knowledge, this study used qualitative methodology to explore views (and related experiences) of Canadian mental healthcare providers about immigration and its relation to psychosis (such as schizophrenia). The research questions of this study were (1) what are barriers and enablers of mental health and other services for Canadian immigrants with psychosis and (2) what are related barriers and enablers for their mental health service providers. The study was conducted in London (Ontario), a city with a diverse immigrant population and a mid-level immigrant concentration, i.e., higher than the Canadian average but lower than the Ontario average (Statistics Canada 2013).

Methods

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional qualitative study. A phenomenological approach (Creswell 2007) was used for the purpose of data collection and analysis in order to address views of mental healthcare providers that are informed by their lived experience (as providers of mental healthcare to immigrants with psychosis). A qualitative data approach was used in order obtain in-depth personal knowledge, considering that not much has been studied on this set of questions. Phenomenology can provide a snapshot of such information.

Participants

A convenience sample of 12 mental healthcare providers was selected for diversity from an academic tertiary mental healthcenter and from a community mental healthcare agency in the region of Southwestern Ontario; note that according to Creswell (2007), six participants are often considered an adequate sample size in phenomenological methodology to explore lived experience. Furthermore, purposive and snowball sampling methods were used to obtain within these two organizations a representative sample of mental healthcare providers representing different disciplines. Participants were included if they (1) had at least 1-year work experience with people with psychosis, (2) provided in the past or present direct care to immigrants with psychosis, and (3) provided voluntary informed consent to participation in the study.

There were 1 male and 11 female participants. Participants varied in their professions: psychiatrist (2), family physician (1), nurse practitioner (2), registered nurse (3), social worker (2), and occupational therapist (2).

At the time that the study was conducted, there were very few local patients who were immigrants with psychosis, and those who were approached refused to participate in the study. We kept our focus on their experience and attempted to study it not through lived experience but rather through informants (their mental healthcare providers).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, after receipt of approval from the local university’s Research Ethics Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were not compensated for their participation in the study.

Data Collection

A semi-structured interview was conducted individually with each participant. Participants were interviewed by two research staff members due to mental health service providers being situated in two different cities (London and Windsor, Ontario). Interviews lasted approximately 1 h and addressed support needs and challenges of immigrants with psychosis, their barriers to using services and programs in health and social areas, as well as the challenges, barriers, and enablers for mental healthcare providers working with them. The interview guide was generated de novo and specifically solicited information regarding the following issues (with prompts when needed for elaboration or clarification): extent of work experience with people who have psychosis; number of immigrants with psychosis seen within 5 years; relation to and knowledge about immigrants with psychosis; processes of immigration to Canada of people with psychosis; expectations regarding immigration of immigrants with psychosis; how immigration to Canada changes the lives, and influences the mental health, of immigrants with psychosis; and barriers and facilitators of mental healthcare for immigrants with psychosis.

All the semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim and validated by trained research staff. All personal identifiers and confidential information were removed from all the transcripts.

Data Analysis

A set of procedures was performed to conduct the analysis of the dataset by integrating thematic analysis. Participants’ transcripts were coded line by line (Glaser and Strauss 1967) and analyzed using a comparative thematic analysis (Boyatzis 1998). To generate themes, participants’ transcripts were reviewed repeatedly to identify key words, phrases, and themes, which were analyzed independently and cross-checked by two researchers. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. Comparison across each code and theme was performed to identify the common patterns and generate thematic categories accordingly. This process was used until theme saturation was achieved. To achieve credibility/trustworthiness, peer debriefing (Lincoln and Guba 1985) and cross-checking were performed among research team members particularly among the first and last authors. Conformability/trustworthiness in this study is indicated by the demonstration of the themes and extraction of the significant statements from transcripts (Lincoln and Guba 1985).

Results

Overall, a majority (75%) of participants indicated that they had only a professional relationship and/or experience with immigrants with psychosis, while 25% of them reported that they had both personal and professional relationships/experiences. Three (25%) participants were first-generation immigrants to Canada. The work experience of participants who provided direct care to people with psychosis ranged from 2 to 10 years. The number of immigrants with psychosis seen by the mental healthcare providers within the last 5 years ranged from 15 to 100. The majority of participants believed that 70% of first episodes of psychosis in immigrants occur after the process of immigration and that most of them either did not have or were not diagnosed with psychosis prior to immigration.

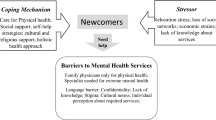

The data were coded and organized in six main themes (with some overlap and with specific subthemes, some of which were found in more than one theme): (1) immigration process, (2) service availability and accessibility, (3) social determinants of health, (4) cultural context, (5) psychosocial stressors, and (6) enablers and facilitators of recovery. These themes and subthemes are summarized in Table 1 and elaborated on and illustrated in the text below. Illustrative quotes for each respective theme are provided in boxes 1–6. Note that the first five themes primarily address barriers and challenges, whereas the last theme addresses enablers and facilitators of recovery.

Immigration Process

The immigration process was considered emotionally taxing. Reasons for immigration, type of immigration (economic, refugees/asylum seekers, or student visa), length of immigration time, its complexity, selection for immigration, hope and expectations, and/or having substantial knowledge about immigration were identified as key indicators of the immigration process potentially triggering the psychosis symptoms (Table 1).

Participants noted that all sources of emotional stress that are involved in the immigration process exacerbate psychosis or may be much more stressful for someone dealing with psychosis. Participants also indicated that there is failure on the part of immigrants to consider challenges and barriers that may be encountered in the new country, which can cause stress beyond the immigration process itself. Participants also indicated that the reasons for immigration and its outcomes are positively biased due to failure to consider the challenges and barriers that may be encountered in the new country. They noted that immigrants have high positive expectations and hopes that they will find “some sort of heaven” upon arrival to Canada, such as improved quality of life, employment, finances, and healthcare—generally seeking a positive change in their lives. Overall, participants believed that, in most cases, their patients’ hopes were met after their move to Canada. However, they stated that facing adversities upon arrival and dealing with unmet expectations/hopes cause great frustration for immigrants and is often associated with emotional consequences. Such emotional consequences also stem from limited knowledge about the immigration process, mental health, and the hardship of adjustments to new life and society. Participants also acknowledged their own relative lack of knowledge regarding the immigration process, which results in failing to better understand and empathize with the experiences that their clients go through, both positive and negative. Box 1 provides an illustrative quote from a participant regarding the immigration process theme.

Box 1 Participant’s quote related to immigration process theme.

Theme 1—immigration process |

P1: “…it’s quite a long and tedious process to get into Canada, especially if you’re thinking of people coming in on a permanent residence category… looked at the time scale for such things to be processed. It takes about 5–6 years before the paperwork is processed…there is a lot of loops that people have to go through, hoops that people have to jump through, to in order to get through…the whole process of immigration. So, filling out forms, knowing how to appeal if there is a decision… I think, can be quite challenging. … and then there’s the health medical review process, I don’t know how rigorous it is….” P4: “My understanding was that their expectations seem to be that their, everything was going to work out great and they can whatever they want. And you know have whatever clothing they want, whatever food they want. And this sounds like a terrible thing to say but, they just really don’t know what’s available. And, you know, what I see is a lot of shock in finding out that the Canadian system isn’t exactly fair either and has a lot of issues as well. There’s that expectation that we’re this free perfect country that everything is good all the time, and everybody shares, and everybody cares about each other, and they’re going to have this wonderful perfect life. They just expect this paradise.” P12: “If it was a negative experience… Maybe even if the process goes smoothly the way I think of it is that it could be a stressor for anybody going from their home country and their friends and their family and now they’re travelling thousands of miles to a country where perhaps they have no supports… I certainly think it could possibly be a trigger.” P4: “The whole fact that it seems to be very messy and that people kind of seem to go all over the place and there’s no set plan. There’s no set plan for, there’s a set plan for taking somebody from a refugee camp but there is no set plan for when they come in. Everything is very disorganized...” |

Service Availability and Accessibility

Participants stated that healthcare services in Canada are easily accessible and free, and most importantly, they are superior and more comprehensive than similar services offered in the immigrants’ country of origin. They stated that their experience is that almost all immigrants with psychosis receive funding coverage for some medications and/or are placed on the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) and receive follow-up services that are funded for them. However, participants believed that immigrants still encounter several obstacles to access mental health services due to lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate information, long waiting times, lack of interpreter services, lack of medical insurance, financial challenges, lack of awareness of services, lack of financial resources, and insufficient collaboration across health, social, and other services. Many participants noted that healthcare is not highly prioritized by immigrants due to limited funds. They reported that a primary reason for not seeking healthcare services is the high cost of insurance that immigrants must pay until the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) becomes available to them. Many of the patients have minimal funds, receive social assistance, and have no other financial supports; such financial burden hinders their urgency in seeking healthcare. Even many that do have a source of income often need to prioritize, and things that are not in need of immediate attention, such as health insurance, are often put on the back burner. Consequently, immigration has serious implications for mental health and related illness: not only do the stressors involved in the move exacerbate the illness, treatment is not easily available nor is it an immediate priority of the immigrant (and/or his or her family), and is surpassed by basic needs, such as food and shelter. Although participants were aware of cultural diversity, they reported that delivering culturally appropriate services to immigrants with different cultural backgrounds is quite challenging, particularly when all information regarding services is provided in English. In attempts to find a physician, immigrants are faced with a dilemma: they can opt for a physician within their cultural community, which, unlike one outside the community, would understand their background, values, and culture. However, many worry about losing the benefit of confidentiality when selecting a physician from their community. They are reportedly worried that information regarding their illness will be disclosed to family or community members. Therefore, clients are conflicted between a potentially unhelpful physician and a loss of confidentiality. These drawbacks may prevent many from seeking help formally. Box 2 provides an illustrative quote from a participant regarding the service accessibility and availability theme.

Box 2 Participant’s quotes related to the service accessibility and availability theme.

Theme 2—service accessibility and availability |

P2: “…I believe that their expectation of a positive change are met when they come here to Canada because the healthcare is accessible to everyone and it’s free, so there is easy access to healthcare and even some of the medications are covered some of them do end up going on ODSP*, and if you get hospitalized you don’t have to pay for it, and there is follow-up services that are arranged. So, in terms of just the illness piece, I think it is definitely better…” P1: “…Lack of awareness of services that are available; not even knowing, for example, who you go through in order to get mental health care. Do you just turn up at Emergency, or do you go to a GP? What if you can’t find a GP? Because not all of them have family doctors, and they may end up in a crisis where they might have to go into the emergency room to get to the right path, or to get the help they need…Does that mean you don’t get health care…who tells you that? I’m not sure if people are aware of how to get health….There are wait-lists for programs so it’s not easy always for people to people to access what they need right away…” P4: “…I don’t know if there are a lot of specialized services to help folks who have a mental illness diagnosis. … I don’t know what the sensitivity or expertise of a lot of healthcare providers are in regards to provision of services especially when it comes to assessments. Um, there were a lot of misunderstandings and misinterpretations which lead to incorrect assessments I find on our healthcare team.” P5: “…Communication is a big barrier,… in order to provide services effectively we need to have an effective interpreter, and has to be a professional interpreter, it cannot be just somebody random, it has to be somebody trained who is trained not to be bias, and how not to try to say what they’re thinking someone is trying to say and say exactly what the person is saying… That might be more difficult to get some of the subtle meanings of what they are saying....”that’s just a standard… that’s very expensive. So cost, is a big issue…” |

Social Determinants of Health

Participants addressed social determinants of health, such as social support. They noted that the immigration process is stressful and results in feelings of isolation if social support is lacking. They argued that prior to moving, it is crucial to look into support systems available as that could be a vital factor in acclimatization and improvement of the mental illness. Despite the well-established healthcare system in Canada that can improve health status, the move may sometimes also result in the loss of social support. This may be because immigrants move here alone or are separated from their natural supports due to different placements upon immigration. Some come from a place with a strong support system of family and friends, to a place where they do not know anyone. They tend to feel isolated as they do not fit in with the new society or are even rejected by their own cultural community in Canada due to their mental illness. This added stress may exacerbate the existing mental illness. With the stress of moving, people have little time to form new relationships, and depending on the country of origin, there may or may not be a native community in the city they immigrate to. In cities where there is a community from their country of origin, the immigrants may fear isolation from their community if they socialized with others outside of that community. This limits their opportunities for new relationships and social support. However, some participants affirmatively stated that many cities in Canada do have numerous and varied cultural communities that provide ample support for those who immigrate.

Box 3 Participant’s quote related to social health determinant theme.

Theme 3—social health determinants |

P3: “…there’s a lack of social support or the immigrant population especially in some of the cultures that, where they come from there is a lot of help that they get from families and friends. And when they do come here they tend to feel isolated because they just don’t fit in with the society …it’s very hard to find people within the same community or even within the same community they would not associate with them because of the mental illness and all that. So, the lack of social support is definitely an issue that some of them talk about…” P11: “…Sometimes some of these people come from families who are very tightly-knit and have parents who are overly protective over them and which may be a normal thing for them, like for an adult to live in a family home with parents, grandparents, kids, like 3 or 4 generations in one house, which is a normal thing in that culture. But when they get here, and then the same thing cannot happen so the families are following them. People tend to think of them as really enmeshed families which may be normal thing for them, but here people say, oh, the family is very intrusive, and the family is very enmeshed, and this kind of thing. So, those cultural things will always come in, I think, as part of the treatment or part of the treatment team and then it can create challenges because people tend to see them as very intrusive families and then that can create challenges within the treatment team…” |

Participants stated that sometimes receiving a lower income prior to immigration, lack of sustainable employment, or being unemployed cause much distress for some immigrants, resulting in social isolation. Overall, participants indicated that there is insufficient social and family support for immigrants who suffer from psychosis. Box 3 provides an illustrative quote from a participant regarding the social determinants of health theme.

Cultural Context

Cultural context was considered by the majority of participants as a main contributor to numerous immigration-related issues such as cultural differences and sensitivity, illicit drug use that is normative in some countries of origin, culture-specific syndromes, and religious beliefs. Additionally, lack of substantial knowledge of various cultural differences was deemed a major obstacle for participants in working with immigrant patients. Apparently, when clients discuss visions related to religion, spirits, or witchcraft, participants stated that they struggle distinguishing whether those are related to the patients’ cultural beliefs or are psychotic symptoms. Furthermore, clients often behave in a customary manner to their culture that is culturally inappropriate in North America. Participants acknowledged that sometimes, they considered those behaviors as bizarre or abnormal which may lead them to misinterpret such behaviors as psychotic symptoms. Thus, participants believed that due to limited knowledge about cultural differences and culture sensitivity, they are prone to misinterpretation and misdiagnosis.

Box 4 Participant’s quote related to cultural context theme

Theme 4—cultural context |

P4: “…Some of the health care professionals may not have a true understanding of the cultural background. And again, especially when you are dealing with psychotic disorders, people tend to have delusions of different kinds, and delusions may be somewhat religious based, or spiritual, they talk about witchcraft … which may be totally acceptable in their culture. And then when you get here and they are talking to someone who has no clue what they are talking about, they think oh my god, this guy, this person is psychotic. But then, it may be something that is normal for them… talking about possessions and cures, cure by god and those kinds of things, which may be normal in their culture, but may not be in another culture. So, definitely the cultural barriers, I think more education about culture is valid, I think it would help everyone...” P7: “…In her community she socialize with, to the best of her ability with other people. So, we were at risk of interpreting her behaviour as paranoid behaviour or anxiety….When in fact it was a cultural barrier, not anything to do with her illness. P13: “...the ability to find a psychiatrist or a psychiatric systems in the language of home is going to be a problem, because probably that would be their best chance of expressing what is going on…” |

Participants stated that without cultural understanding, immigrants’ religions and other culture-specific beliefs may pose obstacles to treatment, including potential misdiagnosis. An example noted was the different views held by different cultures on drug treatments, including both illicit drugs and antipsychotics. For instance, some of the immigrant clients refused such treatment asserting that drugs are unnatural and contradict their beliefs, whereas others indicated that usage of different drugs is a common part of their culture. The latter is common in several cultures despite the fact that such drug use may be a cause of a mental illness or act as a trigger for psychotic episodes, e.g., if the drug has hallucinogenic properties. Box 4 provides an illustrative quote from a participant regarding the cultural context theme.

Psychosocial Stressors

Psychosocial stressors such as fear of separation from children and/or other family; fear of hospitalization; feeling embarrassed, stigmatized, and isolated; being in a stressful environment; and being unable to communicate due to language barriers were identified as potential triggers for increasing the emotional stress in immigrants with psychotic symptoms.

Separation or even the fear of separation from family was deemed by participants as a challenge to recovery and a stressor in immigration. For instance, if a husband immigrates without his wife, the wife might worry about being left alone, having her husband move on with another woman, and have her children taken away from her. More importantly, if the partner suffers from a mental illness, there is a fear that the illness will be used as grounds for divorce. Fear of separation may also occur after the move. Upon immigration, children are sometimes taken away to different host homes, which is not always the best solution. Several participants added that such stress from the separation may greatly hinder the recovery process, as a constant worry about the children is a significant source of stress.

Participants noted that many immigrants with psychosis avoid association with their country of origin communities in Canada, because of the mental illness. Due to the lack of social support and acceptance, many may feel alienated. A participant stated that even simple things, such as diet, may contribute to the feeling of alienation because of the cultural differences. Different cultures have different foods, eat at different times, and have different restrictions on food, and therefore, diet plays a crucial role in the feeling of belonging. Yet, the most commonly mentioned source for feelings of isolation was language barriers. Living in a foreign environment, surrounded by unfamiliar faces, the language barrier was argued to prevent effective communication and acquisition of new acquaintances; in a new culture and with a difficulty in understanding the language and culture itself, many might feel even more removed from the mainstream. Box 5 provides an illustrative quote from a participant regarding the psychosocial stressor theme.

Box 5 Participant’s quote related to psychosocial stressor theme.

Theme 5—psychosocial stressors |

P2: “…Even at best of the time, even if it’s a positive change, sometimes it can be stressful. So for someone with a psychotic disorder coming to a new country, new culture, language barriers, those kinds of things would be hugely impacting them. So someone who is already well off and not symptomatic. That can be point in time when they can decompensate and can precipitate an acute crisis…” P10: “…And then because of the background that they come from, there might be fear of institutionalization, they may feel that if they come into hospital they may be not let go and just left in the hospital, or fear of being over-medicated….And also I think then one of the fears would be because they come from a different cultural background, they come from a different environment totally, … So will the health care professionals and will the health care team understand where they come from? Will they be able to generally connect with them and be able to realize what they are experiencing?” |

Enablers and Facilitators of Recovery

Despite many barriers involved with immigration and psychosis, participants discussed numerous enablers and positive factors that contribute to an easier transition and ultimately to the recovery of many immigrants with psychosis. Such facilitators of recovery included governmental support, healthcare and community support services, as well as cooperation between such agencies. Participants mentioned social services that connect immigrants, especially when faced with a language barrier, to needed resources in the healthcare sector and to cultural groups in their community. Reportedly, the social services available proved to be invaluable to many, and numerous clients are grateful for the services and aid provided. They stated that those services eased their transition to a novel country while dealing with their illness. Participants also highlighted the establishment of collaboration across health and social services at different levels and across different community agencies. They asserted that this leads to address the limited resources and supports needed for effective service provision for immigrants with psychosis. According to their views, establishing collaboration across different services would not only eventually reduce costs but it would also help in sharing the resources and expertise and would be beneficial for clients. Participants also described present community facilities that provide interpreters and rooms for families for short lodging. Employees in the facility also help individuals to engage with the community, e.g., by providing them important information such as locations of banks, grocery stores, and healthcare services. Participants added that these facilities also act as a liaison between immigration services and community partners, thus cooperating with those services to aid clients. Participants recommended that such facilities be present in all cities as they significantly improve the lifestyle of immigrants.

Participants noted that accessibility of healthcare in Canada enables many to obtain treatment that they were unable to access or receive in their country of origin. Participants elaborated that this is due to the fact that in Canada, several medications are covered (particularly if one has disability related insurance or allowance), hospital and physician visits are free of cost, and follow-up services are also arranged. Participants listed education as a great enabler to facilitate the move. They suggested educating immigrants about all the support systems and services available and educating healthcare providers about cultural differences, norms, and religions, as well as further training them in cultural competency. This was believed to improve care as well as to help avoid many challenges encountered due to cultural differences. Further, participants indicated that working with immigrants with psychosis and being exposed to different cultural backgrounds and religions provide a good experience and learning opportunity about cultural context. Professional responsibility and empathy were also considered as positive influencers. Because most of the immigration process occurs in the community, it was also suggested that involvement of a mental health professional at the very beginning stages of immigration would be crucial in facilitating the connections with mental health services and resources as needed. Box 6 provides an illustrative quote from a participant regarding the enablers and facilitators of recovery theme.

Box 6 Participant’s quote related to enablers and facilitators of recovery.

Theme 6—enablers and facilitators of recovery |

P2: “…Immigrants who have psychotic disorders who then come to Canada and then have psychotic disorders, what I have noticed is that they seem, at least the family seem a little more open and getting the help that they need…., I’ve noticed that because it’s much more acceptable to have a mental illness rather than some of the other countries, people or family do, are much more open to talk about some of the abuse or some of the symptoms that they may be experiencing and willing to even accept it. So it may be they are willing to accept the medications too. So I think there is a better chance that people may improve, as compared to if they were back home…” P12: “…Canada has given them better and more opportunities… we work with them through the whole recovery process and the majority of them have moved on from our program …have really voiced that they viewed their mental health to be simple and feeling more well-rounded and also felt that many of them voiced was looked upon holistically, that we just didn’t look at mental health, …we looked at everything that could affect mental health …So they were viewed their mental health as very positive and feeling very positive…” |

Discussion

This qualitative exploratory study found six themes related to the experience of mental healthcare providers in relation to immigrants who have psychosis: immigration process, service availability and accessibility, social health determinants, cultural context, psychosocial stressors, and enablers and facilitators of recovery. The most prominent challenges/barriers that mental healthcare providers encountered while working with immigrants with psychosis were related to cultural context, language, and social and health services and support. Difficulty in communicating symptoms, cultural beliefs and norms, as well as worries and fears posed a barrier to treatment.

Research has shown that misdiagnosis of psychotic disorders occurs with immigrants and refugees from all racial-ethnic backgrounds and often results in overdiagnosis of psychotic disorders rather than underdiagnosed (Adeponte et al. 2012; Cantor-Graae and Selten 2005; Minsky et al. 2003; Mukherjee et al. 1983; Neighbors et al. 1989; Sohler and Bromet 2003; Tarricone et al. 2015). Some follow-up studies have demonstrated no evidence of greater diagnostic instability overtime (Takei et al. 1998; Harrison et al. 1999; Cantor-Graae and Selten 2005; Selten and Hoek 2008). Indeed, previous research shows that there are mixed findings in terms of misdiagnosis. However, this study brought evidence in support of misdiagnosis as reported directly by clinicians with a wealth of experience in relation to psychotic disorders, although it is not quantitatively measured. Regarding the etiology, it was not part of the study, but the information on triggers of psychosis was derived from clinicians’ statements. This study found that cultural and social backgrounds can considerably contribute to diagnostic bias by greatly influencing the manner in which psychotic disorders are communicated to and understood by clinicians (Hickling et al. 1999; López and Guarnaccia 2005). Failing to account for unfamiliarity with the cultural context of immigrant patients, clinicians may misinterpret psychotic symptoms by mistaking cultural beliefs and experiences for psychopathology (Veling and Susser 2011; Zandi et al. 2008). Our study found that clinicians acknowledge their personal bias in clinical judgment towards immigrants while assessing and diagnosing them, recognizing the lack of knowledge about cultural differences and/or differences in symptomatic expression of the same illness across different cultures (Leong and Lau 2001). Focusing on practitioners’ skills, Kirmayer (2012) emphasized that the power imbalance in the clinical encounter is due to lack of cultural (including language) competency—the capacity of practitioners and health services to respond appropriately and effectively to patients’ cultural backgrounds, identities, and concerns (Brach and Fraser 2000). Hence, practitioners can acquire specific knowledge, attitudes, and skills that will improve their delivery of effective culturally appropriate and responsive mental health services as well as reduce health disparities (Kirmayer 2012).

We also found that language played a crucial role in the communication between immigrants with psychosis and mental healthcare providers, particularly when interpretation services were either unavailable or restricted due to the high cost, e.g., in having interpreter services for all clinical visits. Lack of communication due to a language barrier and poor health literacy emerged as a major challenge that affected access to services and support. However, even when interpretation services were available, mental healthcare providers were rarely taught how to use them. In addition, it was disputed as to whether the same quality of treatment can be delivered through an interpreter as compared to when the service provider speaks the patient’s language, and whether the interpreter has sufficient knowledge about medical terms, especially in relation to mental illness. Poor quality of interpretation was also seen as a challenge for the mental healthcare providers, as it often leads to misunderstanding and difficulty in making an accurate diagnosis. Consistent with previous research (Stewart et al. 2011), this study demonstrated that the lack of and/or inadequate language impedes the immigrants’ settlement and integration into the new society. It also negatively impacts their navigation of the health system and access to health services and obstructs social inclusion, gaining employment, maintaining self-identity, and social status.

While the language barrier issue may be solved by using healthcare providers from one’s native community, our study revealed that some immigrants with psychosis face a dilemma opting to receive care from a physician within their own community, which would mean an understanding of their background, values, and culture. However, this was met with fear of compromised identiality seeing as the physician is from their community and thus information about their mental illness may be disclosed to family or community members. These drawbacks may prevent many immigrants from seeking help formally.

Another important issue found in this study is the discrepancies that exist between the high expectations and hopes of immigrants and the subsequent disappointment after immigration, which may trigger depressive and psychotic symptoms. The great frustration experienced by immigrants may not be caused by the social status per se, but it occurs due to the discrepancy that exists between the achievement and aspirations of immigrants. This, in turn, may be linked with psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia (Tuckman and Kleiner 1962).

As reported elsewhere, lack of social and family support, challenges in accessibility and availability of services, financial hardship, and stigmatization greatly contribute to social isolation and stress, poverty, decreased feelings of dignity and self-worth, lack of employment, substandard housing, and homelessness. These result in the triggering, exacerbation, and/or persistence of psychotic symptoms (Selten and Cantor-Graae 2005; Stewart et al. 2011). The issue pertaining to mental healthcare is social inequality. People with mental illness face not only social exclusion but also exclusion from the healthcare system. Due to unjust social structure, immigrants with a mental disorder are subjected to societal abuse (Benbow 2009). As reported in this study and elsewhere, immigrants experience forms of exclusion related to the immigration process, access to services and discrimination that result in the prevention of meeting basic human needs, and exclusion from many aspects of society. More important, however, are the legal and practical implications for social exclusions that are associated with each particular immigration status. A lengthy and extremely complex process of obtaining the status of refugee claimants, called a “legal limbo” period, leads to substantial delays. Such delays prolong the time during which refugees lack access to social services, the labor market, and an ability to obtain their permanent citizenship (Omidar and Richmond 2003) in order to have the right to vote, get loans, or work in particular occupations. This legal limbo denies help and opportunities for those who need it most after dealing with extreme stress involved in immigration and the high expectations for a better life in the new country (Mohamed 2002). According to Power and Faden (2006), failure to achieve a sufficient level in one dimension (e.g., health, personal security, respect, reasoning, attachment, and self-determination) can lead to failure to achieve a sufficient level in other dimensions because their cumulative effect on human well-being depends on their causal interactions. Therefore, the existence of inequalities that prevent access to social, economic, political, and environmental well-being points out the need for social justice advocacy. According to Perez and Martinez (2008), community health workers play a pivotal role in advocating for social justice, in helping to advise new immigrants on their rights on immigration laws and how to navigate bureaucratic systems, recounting the realities of exclusion and suggesting remedies for it due to their direct interaction with vulnerable populations.

Furthermore, immigrants are often torn between their native cultural values and adapting into the new culture. Cultural differences, as well as discrimination and racism that may result from those, are a source of isolation and alienation in immigrants. In such situations, social support is invaluable.

In spite of the discussed challenges, we found that healthcare accessibility in Canada enables many immigrants with psychosis to obtain treatment that was unavailable to them in their country of origin. This is due to the fact that several medications can be fully funded, hospital and physician visits are free, and follow-up social and health services can also be arranged. However, in Canada, regardless of progress, there are few achievements in reducing the country’s health disparities, and significant gaps prevail (Hankivsky and Christoffersen 2008). To address these, Harvisky and Christoffersen (2008) proposed the intersectional paradigm, a normative framework that captures the complexity of lived experiences and concomitant, interacting factors of social inequality, which, in turn, are keys to understanding health inequalities. Others (Baylis et al. 2008) proposed an ethics framework for public health that it is constructed based on the notions of autonomy, social justice, and solidarity, paying specific attention to the vulnerability of subpopulations lacking in social and economic power. Gostin and Powers (2006) emphasized the importance of building public health services on social justice understandings that can generate important policy imperatives for improving the public health system, reducing socioeconomic disparities, addressing health determinants, and planning for health emergencies based upon the needs of the most vulnerable populations.

A somewhat unexpected finding of our study is the mental health providers’ belief that the majority of immigrants were not diagnosed with or did not have psychosis prior to coming to Canada. Indeed, some reported that they believe that the acute psychotic episode happened during the immigration process. This supports the assertion that immigration is a particularly stressful experience (Levitt et al. 2005) and that it should be addressed across sectors to mitigate the risk of immigrants developing psychosis in order to support their well-being and contribution to the receiving society. Indeed, severe social, economic, and health inequalities are often compounded by national immigration policies and structural constraints in receiving countries (Anderson et al. 2015).

There are several limitations to our study. We used a non-controlled design and studied a small sample; hence, findings cannot be robustly generalized. Nevertheless, our sample included clinicians who had an immigrant background as well as cross-cultural skills training, and thus, they could mitigate this risk. Further research is required with larger samples and more rigorous study designs, such as a mixed methods study. Another limitation of this study is that there were no data provided from immigrants with psychosis and/or their families in order to compare their views with those of healthcare providers; future research should study the views of service users and their families. In addition, there were no data provided to determine the differences that may exist between economic immigrants vs. asylum seekers in relation to risk of development of psychosis, particularly when trauma of the refugees is not recognized. Also, as the study was conducted in Southwestern Ontario, it may represent only healthcare practices related to immigrants with psychosis in this region/jurisdiction rather than elsewhere; study of other geographical areas in Canada and elsewhere in relation to this subject matter would be helpful. Future research may benefit from using a mixed methods approach, e.g., quantifying the extent of challenges faced by immigrants with psychosis while clarifying qualitatively their first-person experiences addressing such challenges.

Conclusion

Results of this study suggest that there are various areas for intervention to reduce disparities for immigrants with psychosis in their use of social and healthcare services. More research is needed in relation to immigration of people with psychosis, particularly in relation to their responses within receiving communities and how to support their integration with a person-centered and culturally safe approach.

References

Adeponte, A. B., Thombs, B. D., Groleau, D., Jarvis, E., & Kirmayer, L. J. (2012). Using the cultural formulation to resolve uncertainty in diagnoses of psychosis among ethnoculturally diverse patients. Psychiatric Services, 63(2), 147–153.

Anderson, K. K., Cheng, J., Susser, E., McKenzie, K. J., & Kurdyak, P. (2015). Incidence of psychotic disorders among first-generation immigrants and refugees in Ontario. CMAJ, 187(9), E279–E286.

Baylis, F., Kenny, N. P., & Sherwin, S. (2008). A relational account of public health ethics. Public Health Ethics, 1(3), 196–209.

Benbow, S. (2009). Societal abuse in the lives of individuals with mental illness. The Canadian Nurse, 105(6), 30–32.

Bourque, F., van der Ven, E., & Malla, A. (2010). A meta-analysis of the risk for psychotic disorders among first- and second-generation immigrants. Psychological Medicine, 41(5), 897–910.

Boyatzis, R., & E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brach, C., & Fraser, I. (2000). Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Medical Care Research and Review, 57(suppl I), 81–217.

Bhugra, D. (2000). Migration and schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102, 68–73.

Cantor-Graae, E., & Selten, J. (2005). Schizophrenia and migration: a meta-analysis and review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(1), 12–24.

Coid, J. W., Kirkbride, J. B., Barker, D., Cowden, F., Stamps, R., Yang, M., & Jones, P. B. (2008). Raised incidence rates of all psychoses among migrant groups: findings from the East London First Episode Psychosis Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(11), 1250–1258.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Desjarlais, R., Eisenberg, L., Good, B., & Kleinman, A. (1995). World mental health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Gostin, L. O., & Powers, M. (2006). What does social justice require for the public’s health? Public health ethics and policy imperatives. Social justice demands more than fair distribution of resources in extreme public health emergencies. Health Affairs, 25(4), 1053–1060.

Hankivsky, O., & Christoffersen, A. (2008). Intersectionality and the determinants of health: a Canadian perspective. Critical Public Health, 18(3), 271–283.

Harrison G, Amin S, Singh SP, Croudace T, and Jones P (1999) Outcome of psychosis in people of African–Caribbean family origin. British Journal of Psychiatry. 175:43–49

Hjern, A., Wicks, S., & Dalman, C. (2004). Social adversity contributes to high morbidity in psychoses in immigrants—a National Cohort Study in two generations of Swedish residents. Psychological Medicine, 34(6), 1025–1033.

Hickling, F. W., McKenzie, K., Mullen, R., & Murray, R. A. (1999). Jamaican psychiatrist evaluates diagnoses at a London psychiatric hospital. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 283–285.

Kennedy, S., McDonald, J.T., Biddle, N. (2006). The healthy immigrant effect and immigrant selection: evidence from four countries : social and economic dimensions of an aging population research papers. http://socserv.mcmaster.ca/sedap/p/sedap164.pdf

Kirkbride, J. B., & Hollander, A.-C. (2015). Migration and risk of psychosis in the Canadian context. CMAJ, 187(9), 637–638.

Kirmayer, L. J. (2012). Cultural competence and evidence-based practice in mental health: epistemic communities and the politics of pluralism. Social Science of Medicine, 75(2), 249–256.

Lauderdale, D. S., Wen, M., Jacobs, E. A., & Kandula, N. R. (2006). Immigrant perceptions of discrimination in health care: the California Health Interview Survey 2003. Medical Care, 44910, 914–920.

Leff, J. (2006). Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in ethnic minority groups; results from the MRC AESOP study. Psychological Medicine, 36(11), 1541–1550.

Leong, F. T. L., & Lau, A. S. L. (2001). Barriers to providing effective mental health services to Asian Americans. Mental Health Services and Research, 3(4), 201–214.

Levitt, M. J., Lane, J. D., & Levitt, J. (2005). Immigration stress, social support, and adjustment in the first postmigration year: an intergenerational analysis. Research in Human Development, 2(4), 159–177.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc..

López, S.R, & Guarnaccia, P.J. (2005). Cultural dimensions of psychopathology: the social world’s impact on mental illness. In: Psychopathology. Foundations for a Contemporay Understanding. Maddux JE, Winstead BA (Eds). Erlbaum, NJ, USA, p. 21–42.

Mallet, R., Leff, J., Bhugra, D., Pang, D., & Zhao, J. H. (2002). Social environment, ethnicity and schizophrenia: a case-control study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatry Epidemiology, 37(7), 329–335.

Menezes, N. M., Georgiades, K., & Boyle, M. H. (2011). The influence of immigrant status and concentration on psychiatric disorder in Canada: a multi-level analysis. Psychological Medicine, 41(10), 2221–2231.

Minsky S, Vega W, Miskimen T, Gara M, and Escobar J. (2003). Diagnostic patterns in Latino, African American, and European American psychiatric patients. Archive of General Psychiatry. 60(6):637–644.

Mohamed, H. 2002. Neither Here Nor There: The Social Cost of Refugees in Limbo. INSCAN 15(3) (winter). http://www3.carleton.ca/cimss/inscan-e/v15_3e.pdf

Morgan, C., Kirkbride, J., Hutchinson, G., Craig, T., Morgan, K., Dazzan, P., Boydell, J., Doody, G. A., Jones, P. B., Murray, R. M., Leff, J., & Fearon, P. (2008). Cumulative social disadvantage, ethnicity and first-episode psychosis: a case-control study. Psychological Medicine, 38(12), 1701–1715.

Morgan, C., & Hutchinson, G. (2010). The social determinants of psychosis in migrant and ethnic minority populations: a public health tragedy. Psychological Medicine, 1, 1–5.

Mukherjee S, Shukla S, Woodle J Rosen AM, and Olarte S. (1983) Misdiagnosis of schizophrenia in bipolar patients: a multiethnic comparison. American Journal of Psychiatry. 140(12):1571–1574.

Neighbors, H., Jackson, S., Campbell, L., & Williams, D. (1989). The influence of racial factors on psychiatric diagnosis: a review and suggestions for research. Community Mental Health Journal, 25(4), 301–311.

Omidar, R. & Richmond, T. (2003). Immigrant settlement and social inclusion in Canada. http://maytree.com/PDF_Files/SummaryImmigrantSettlementAndSocialInclusion2003.pdf

Patino, L. R., Selten, J. P., Van Engeland, H., Duyx, J. H., Kahn, R. S., & Burger, H. (2005). Migration, family dysfunction and psychotic symptoms in children and adolescents. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 442–443. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.5.442.

Perez LM and Martinez J. (2008). Community Mental Health Workers: Social justice and policy advocates for community health and well-being. American Journal of Public Health. 98(1):11–14.

Powers, M., & Faden, R. (2006). Social justice: the moral foundations of public health and health policy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Prior J, & Harfield S. (2012). Health, well-being and vulnerable populations. In book: International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home, Publisher: Elsevier, Editors: Susan J. Smith, pp.355–361 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-047163-1.00036-9.

Roth, G., Ekblad, S., & Agren, H. (2006). A longitudinal study of PTSD in a sample of adult massevacuated Kosovars, some of whom returned to their home country. European Psychiatry, 21, 152–159.

Rudnick, A., & Lundberg, E. (2012). The stress vulnerability model of schizophrenia: a conceptual analysis and selective review. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 8(4), 337–341.

Seeman, M. V. (2010). Canada: psychosis in the immigrant Caribbean population. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764010365979.

Selten, J. P., & Cantor-Graae, E. (2005). Social defeat: risk factor for schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(Suppl.51), s9–s12.

Selten, J. P., & Hoek, H. W. (2008). Does misdiagnosis explain the schizophrenia epidemic among immigrants from developing countries to Western Europe? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(12), 937–939.

Smith, G. N., Boydell, J., Murray, R. M., Flynn, S., McKay, K., Sherwood, M., & Honer, W. G. (2006). The incidence of schizophrenia in European immigrants to Canada. Schizophrenia Research, 87(1–3), 205–211.

Sohler NL and Bromet EJ (2003). Does racial bias influence psychiatric diagnoses assigned at first hospitalization? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 38(8):463–472.

Statistics Canada. 2013. London, CY, Ontario. National Household Survey (NHS) Profile. 2011 National Household Survey. Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 99–004-XWE. Ottawa.

Stewart, M., Shizha, E., Makwarimba, E., Spitzer, D., Khalema, E. N., & Nsaliwa, C. D. (2011). Challenges and barriers to services for immigrant seniors in Canada: “you are among others but you feel alone”. International Journal of Migration, Health & Social Care, 7(1), 16–32.

Takei N., Persaud R., Woodruff P., Brockington I., Murray R.M. (1998). First episodes of psychosis in Afro-Caribbean and White people. An 18-year follow-up population-based study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 172:147–153.

Tarricone, I., Tosato, S., Cianconi, P., Braca, M., Fiorillo, A., Valmaggia, L., & Morgan, C. (2015). Migration history, minorities status and risk of psychosis: an epidemiological explanation and a psychopathological insight. Journal of Psychopathology, 21, 424–430.

Tuckman, J., & Kleiner, R. J. (1962). Discrepancy between aspiration and achievement as a predictor of schizophrenia. Behavioural Science, 7(4), 443–447.

Veling, W., & Susser, E. (2011). Migration and psychotic disorders. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 11(1), 65–76.

Wamala, S., Merlo, J., Boström, G., & Hogstedt, C. (2007). Perceived discrimination, socioeconomic disadvantage and refraining from seeking medical treatment in Sweden. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 61, 409–415.

Weiser, M., Werbeloff, N., Vishna, T., Yoffe, R., Lubin, G., Shmushkevitch, M., & Davidson, M. (2008). Elaboration on immigration and risk for schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine, 38(8), 1113–1119.

Whitley, R., Kirmayer, L. J., & Groleau, D. (2006). Understanding immigrants' reluctance to use mental health services: a qualitative study from Montreal. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 205–209.

Zandi, T., Havenaar, J. M., Limburg-Okken, A. G., Van Es, H., Sidali, S., Kadri, N., Van Den Brink, W., & Kahn, R. S. (2008). The need for culture sensitive diagnostic procedures: a study among psychotic patients in Morocco. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatry Epidemiology, 43, 244–250.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the research staff and others, i.e., Fan Wu, Sara Asmail, Yewande Anozie, Seema Rathod, and Brittany Rodrigues, who assisted with transcribing, validating, and coding the data. This project was funded in part by the St. Joseph’s Health Care Foundation, London Ontario, Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Location: This research study was conducted in London, ON, Canada at Regional Mental Health Care London/Lawson Research Health Institute.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pallaveshi, L., Jwely, A., Subramanian, P. et al. Immigration and Psychosis: an Exploratory Study. Int. Migration & Integration 18, 1149–1166 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-017-0525-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-017-0525-1