Abstract

The objective of this study was to explore housing insecurity among women newcomers to Montreal, Canada. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 26 newcomer women who had experienced housing insecurity and five women’s shelter service providers. The primary cause of housing insecurity for newcomer women was inadequate income in the face of rapidly rising housing costs, coupled with unfamiliarity with the dominant culture and the local housing system. Specific events often served as tipping points for immigrant women—incidents that forced women into less secure housing. To avoid absolute homelessness, most women stayed with family, couch surfed, used women’s or educational residences, shared a room or an apartment, lived in hotels, single rented rooms, or transitional housing. These arrangements were often problematic, as crowded conditions, financial dependency, differing expectations and interpersonal conflicts made for stressful or exploitive relationships, which sometimes ended abruptly. Only two of the 26 women interviewed described their current living situation as stable. Based on the findings on the study, we recommend training for housing and immigration service providers, wrap-around services in terms of health, housing and immigration settlement programs that take into account a broad range of immigration statuses and transitional housing that caters to the specific needs of migrant women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Previous research has documented the ways in which gender intersects with both housing risk (Klodawsky 2006; Novac 1996) and with immigration status (Klodawsky et al. 2015; Paradis et al. 2008). In both cases, women face heightened vulnerabilities in the quest for a safe and secure home, whether in terms of material shelter (when gender intersects with housing risk) or the legal right to remain in the country (when gender intersects with immigration status). The study presented in this article adds to our understanding by bringing together the factors of gender, housing and immigration to understand migrant women’s experiences on the spectrum of housing insecurity. The objective of this study was to uncover and explore the continuum of housing insecurity—from unaffordable, crowded or poor quality housing to living in the streets—among women newcomers to Canada. We sought to address the paucity of research on this topic, and, based on what we learned, we offer recommendations for the development of responsive policies and services grounded in the voices of those directly affected.

In this article, we begin with a review of existing literature on gender, housing and immigration status before turning to the description of our research methods. We then present the project’s results in terms of the profile of women who participated in interviews and the major factors contributing to their housing insecurity. Of particular interest are the “tipping points” that seem to push them into difficult situations. The documentation and analysis of these tipping points helped us to contextualize the numerous strategies these women used to address their housing problems, including the use of community and social services. We conclude with recommendations for ways in which community and social services might better help newcomer women avoid or escape housing insecurity.

Research Context

Our understanding of newcomer women’s experiences with homelessness and housing insecurity is informed by the literature on the intersection of the following: (1) gender and housing, (2) gender and immigration status and (3) immigration status and housing. Here, we review some of the most important concepts.

Existing literature still associates homelessness with men and gives relatively little visibility to gender variables. Sylvia Novac (1996), a pioneer in emphasizing gender dimensions of housing, argued that homelessness has been “…viewed as a male experience and problem, gender has not been a factor in much of the literature on this topic” (p.iii). However, this discourse is changing as growing numbers of women began resorting to women’s shelters (Paradis et al. 2008), which is bringing more visibility to women’s homelessness and challenging the common—applied—understanding of homelessness as “only about the absence of a roof” (Klodawsky 2006, p. 368). In Montreal, it is estimated that 23 to 40 % of the homeless population are women (Duchaine 2013; MSSSQ 2008), and this number is correlated by recent data from the municipality de Montreal (Montreal 2014). In fact, female homelessness is a complex spectrum that manifests mainly in hidden homelessness (Anucha et al. 2007; Kilbride et al. 2006; D‘Addario et al. 2007). It has been documented that “women have more frequently used informal strategies, such as staying with friends and family or attaching themselves to housed men, in order to avoid either the streets or emergency shelters” (Klodawsky 2006, p. 368). Even when shelters are used, those devoted to women tend to be much smaller and less visible than those for men (Klodawsky et al. 2015). Few shelters are “mandated or adequately resourced to meet the needs of this population [immigrant or refugees]” and, in turn, “immigrant serving agencies are also ill-equipped and under-funded and not mandated to address housing issues” (Pruegger and Tanasescu 2007, p. 5).

These “housing arrangement” strategies are “intricately tied to the sexual division of labour and to women’s social vulnerabilities as daughters, wives and mothers” (Klodawsky 2006, p. 367). In this broad picture, the housing status and vulnerability to homelessness of women holding particular social locations such as racialized women, single mothers or immigrant women seem to stem from complex relations of class, gender and race (Novac 1996). The literature has long shown that “market dominated housing policies disadvantage women” (Novac 1996, p. 2).

Gender also intersects with immigration status. Migration represents a social and spatial mobility; however, women do not seem to enjoy its benefits as much as men. Research has documented that migration has a strong gendered dimension at each of the different steps of the migratory project and that “the migration experience of women is fundamentally different from that of men” (Bierman et al. 2009, p. 103). For example, Ray and Rose (2011) examined the gender divergence of immigration experiences between male and female immigrants to Canada and the USA, from the decision to migrate to the experiences of settlement and everyday life. They demonstrated the impact of “wage penalty on the labour market”, racism and systemic social discrimination on women’s experiences of migration and settlement. Kofman (1999) has denounced the way in which both research and policy tend to operate under the assumption of a model male-led immigration with women only following as part of the family unit.

The model of immigration based on men’s experiences is reiterated in Canadian policy. First, there is an over-representation of women in the family reunification category (Chicha 2009; Ray and Rose 2011). Second, women disproportionately experience professional and social disqualification (Boudarbat and Gontero 2008; Boulet 2012; Chicha 2009; Ray and Rose 2011). Precarious immigration status puts women in situations of dependency from their male partners (Goldring et al. 2009; Thurston et al. 2013), which makes them at risk of abusive relationships. Research has proven that the limited knowledge about their rights and the complexity of the system as well as the fear of losing the legal status, their children or to deal with officials (police), prevents immigrant women from reporting the abuse or violence (Kissoon 2010; Mosher 2009) and from securing themselves a stable legal status (Kissoon 2010).

Immigrant women present higher risks of economic inequality (Ledent 2012), low income and poverty (Kazemipur and Halli 2001). The weak economic integration of immigrant women (and men) is linked to multiple barriers to employment, with many immigrants adopting the strategy of the “survival employment” (Creese and Wiebe 2012, p. 56). Immigrant women experience persistent deskilling (Chicha 2009; Paradis et al. 2008) although some studies have shown improvements on the long run (Creese and Wiebe 2012).

Interpersonal violence also contributes to housing insecurity of newcomer women (Moynihan et al. 2008; Thurston et al. 2006). A 2008 Québec Parliamentary commission identified recent immigrant women as over-represented in the cases of conjugal violence appearing before the courts. Some studies have identified clear connection between family violence, immigration and homelessness of women and portrayed a different profile to this form of violence (Thurston et al. 2013). Personal relations play out in other ways, as immigrant women are more interpersonally dependent with family members (Neufeld et al. 2002), have greater childcare responsibilities (Tischler et al. 2007) and sometimes extended family’s responsibility that require them to send remittances to the home country (Ives et al. 2014).

Housing experiences also intersect with immigration status. The housing experiences of migrant women have been the subject of little investigation (Ray and Rose 2011); they are typically subsumed under the gendered categories of women’s homelessness or newcomers’ housing insecurity (see for example, Hiebert 2009; Murdie 2008; Preston 2011; Teixeira 2009). Newcomers in general have higher rates of poverty (Galabuzi 2006), higher likelihood of experiencing precarious and low-paid employment (Kissoon 2010; Vosko 2006) and are more likely than the Canadian-born population to spend more than half of their household incomes on housing (Hiebert et al. 2006; Hiebert 2009; Preston 2011; Preston et al. 2009; Rose 2001), much of which is inadequate (Leloup and Zhu 2006) and situated in declining neighbourhoods (Carter and Osborne 2009; Carter et al. 2009). The portrait of housing insecurity for newcomers is linked to limited, if not inexistent, social networks and social capital (Hiebert et al. 2005), isolation and social exclusion (Danso 2002; Kissoon 2010; Ray and Preston 2009). Financial difficulties lead immigrants to experience short single or multiple episodes of homelessness more often than among the Canadian-born population (Klodawsky et al. 2015; Preston 2011; Preston et al. 2009). Within this broad picture, asylum seekers and refugees report the most severe housing difficulties because they are subjected to greater difficulties in the private housing market (Rose and Charrette 2011; D’Addario et al. 2007; Preston 2011)

This serious housing insecurity amongst newcomers exposes them to a higher risk of homelessness, with immigrant women reporting perceptions of “greater personal discrimination [in housing] as well as some aspects of group discrimination than men” (Dion 2001, p. 535). In this regard, refugee claimants seem to have the most fragile profile due to their immigration status (Hiebert 2009; Murdie 2008; Rose and Charrette 2011). However, the profile of homeless immigrants is substantially different from their domestic counterparts (Hiebert et al. 2005), and they seem to be at risk of homelessness “even without factors that often contribute to homelessness in the general population” (Chiu et al. 2009). Indeed, homeless immigrants are documented to be healthier, less likely to suffer from chronic diseases, mental health issues and/or substance abuse than their non-immigrant counterparts (Chiu et al. 2009); they face mainly “physical/emotional abuse” and family issues (D’Addario et al. 2007; Hiebert et al. 2005). Despite this, homeless immigrants are underrepresented in shelters, and they seem to rely more on support from ethno-cultural communities (D’Addario et al. 2007; Hiebert et al. 2005).

In Montreal, the situation of immigrant women echoes the portrait prevailing in the rest of Canada: Women, especially immigrant women, face discrimination in the housing market. Montréal is the main gateway (70 %) for immigrant women in Quebec, and this population falls in the poorest segments of the population (Conseil des Montréalaises 2006). Immigrant women are disadvantaged in the housing market because of their lack of French language knowledge, lack of knowledge about local housing market rules and regulations and about their rights as renters (Rose and Charrette 2011). In line with this, the Conseil des Montréalaises (2006) recommends increasing social and subsidized housing to face the growing demand of immigrant families with children as it is reported that 2/3 of people on Montreal’s social housing waiting lists were born outside Canada and that 9/10 of those waiting for family-sized housing (3+ bedrooms) were immigrants..

For all of these reasons, this Montreal-based study has focused on women newcomers given the reality that housing insecurity is a gendered and immigration-related phenomenon (Walsh et al. 2009).

Methods

Our methods for this exploratory study were designed around the idea that the direct experiences of persons with insecure housing need to be heard to inform solutions (Acosto and Toro 2001; Walsh et al. 2010a, b). Inclusion of the perspectives of those most affected by an issue helps to ensure that policies and interventions are responsive to their needs (Lombe and Sherraden 2008). In addition, “inclusion of vulnerable groups in the policy process sends a message that they matter, they have a stake in society, they have a voice, and the right to be heard” (Lombe and Sherraden 2008, pp. 204–205).

An exploratory, qualitative, methodological approach to understanding the experiences and needs of homeless newcomer women was most appropriate for this investigation as little research had been conducted on this topic and the ongoing vulnerability of these women posed both risks and challenges to engagement. Face-to-face individual interviews allowed us communicate through a medium that was familiar to the women, many coming from traditions where oral expression was valued over the written word. In addition, this dialogue reduced the risk of misunderstandings caused by language and cultural barriers as the researcher could follow the direction the women provided rather than being limited to an external form of data collection.

Semi-structured, open-ended interviews lasting approximately 1 h were conducted with a sample of 26 newcomer women in Montreal, Canada, in February to May of 2011. Potential participants were invited to contact us directly through advertisements in public places as well as in collaboration with community organizations: women’s centres, homeless shelters, crisis centres, domestic violence shelters, immigrant settlement agencies and ethnic associations.Footnote 1 To participate in the study, newcomer women (foreign-born and having arrived within the past 10 years) had to self-identify as having experienced housing insecurity. We wanted to capture the diversity of immigrant women’s experiences; so, we adopted a definition of housing insecurity that spanned the spectrum from the absolute homeless, such as those residing in shelters to the invisible homeless, such as those living with friends or family, to those at risk of homelessness, such as those living in substandard housing or are at risk of losing their homes (Ben Soltane et al. 2012; Echenberg and Jensen 2008).

An effort was made to recruit women with a diversity of immigrant statuses—permanent residents, temporary foreign workers, refugee claimants and undocumented women—and diversity in ethnicity, race, country of origin, family composition, sexual orientation, age and range of physical and mental ability. The team was prepared to work with translators if respondents were unable to communicate comfortably in English, French or Spanish, but no such person contacted us.Footnote 2 Bilingual, graduate-level social work students were recruited as research assistants for their experience in working with immigrants or homeless populations. They were trained in interview techniques and were advised on local support services for immigrant women for when referrals were necessary.

The location and time of the interview varied according to participant need. So that participants could best express themselves, interviews were done in English or in French, depending on their preference. Once participants had given informed consent, the interview questions focused on five themes: (1) current demographics and immigration history, (2) current health and well-being, (3) history of housing and home insecurity, (4) current situation and (5) survival strategies. Participants were given an honorarium for their participation ($25 CAD) and reimbursed for any travel and childcare expenses. In addition, researchers conducted face-to-face interviews with five key informants working in four local women’s shelters. The semi-structured, open-ended questions were designed to gather information about newcomer women’s homelessness or housing insecurity from a service provider’s perspective. They were asked to describe best practices and challenges in serving the target population. Shelters were offered a $100 donation in appreciation of the participation of their staff member in an interview.

All data collection followed standard ethnographic techniques, employing an active and dialogical interview process (Holstein and Gubrium 1995; Stewart 1998). The interviews were transcribed and then analyzed using the constant comparative method (Dye et al. 2000). Interviews were coded and explored using NVIVO software, a qualitative data management tool. Themes and sub-themes related to the overarching research areas of focus were then identified. Each theme and sub-theme is presented using thick description in the form of illustrative quotes drawn from the participant interviews. Although we will not discuss it here, this project took an innovative, arts-based approach to validating and disseminating our results, using both textile art and found poetry as tools to reach community members.Footnote 3

Results

Interviewed women ranged in age from 22 to 64 and came to Canada from 14 different countries. Most of the women were permanent residents or citizens at the time of the interview, several of whom had initially arrived with temporary status (e.g. refugee claimant, temporary foreign worker). Of the three women who were undocumented, two described having escaped situations of violence and intended to file for refugee status. The third was a graduate student appealing an expired student visa. The majority of the women were not currently married. Of the seven women who had spouses, five had partners who were living in their country of origin. Twelve of the women had children, with seven women having two or three children for whom they were the primary caregivers (see Table 1).

Participants had come to Canada for a variety of reasons: several had come as independent immigrants while some were invited as skilled workers due to their professional and educational aptitudes. Others came as students or had left secure and well-paid jobs with the intention of advancing their qualifications here in Canada. Many who came to Canada involuntarily were fleeing political and/or personal violence in their home countries. Two women arrived in Canada reluctantly following their spouses. One woman arrived in the context of an arranged marriage to a man from her home country who had earlier immigrated to Canada. While housing insecurity was not limited to any particular immigration status in our sample, the level of vulnerability to exploitation was greater for those who felt that they were not in a position to assert their legal rights. Undocumented women in particular were susceptible to abuse as their survival literally depended on others, be it for an under-the-table job, a place to sleep or daily necessities.

In speaking with these women, we identified three major themes: (1) factors which contributed to women’s housing insecurity; (2) incidents of crisis or tipping points which preceded bouts of housing instability; and (3) strategies that women employed to avoid absolute homelessness. Each of these themes is presented with illustrative quotes, some of which have been translated from French.

Contributing Factors

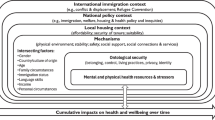

The factors contributing to insecure housing were portrayed by shelter workers and participants alike as complex, multiple and interrelated at the political, social and personal levels. Table 2 shows the reasons for ongoing housing insecurity for respondents. The first column outlines experiences migrant women share with Canadian-born women; the second column relates causal factors unique to immigrant women. Poverty was cited by our respondents as the primary reason for housing insecurity, it is notable, however, that their financial pressures differed from Canadian-born women (Ives et al. 2014). Balancing the expenses of immigration, their overseas family’s dependence on women’s remittances, and low incomes, women were often in a situation where they could not afford secure housing.

Low incomes were usually due to unemployment or underemployment. For women whose prior education and qualifications had not helped them to find employment in Canada, the amount of social assistance they received was not adequate to cover living expenses. Many depended on food banks and non-profit organizations to assist them in meeting their basic needs. Others were relying on student loans or the meagre funding provided by the educational institutions that they attended. Women were constantly juggling the costs of rent, food, clothing, transportation and, for many, remittances to family back home and immigration fees. Some were worried about meeting the basic needs of themselves and/or their family. This respondent described her daily realities in this way:

I was relying on that maternity benefit, which was $400 every 2 weeks. It was very helpful, but not enough… I kept expressing milk, which I did not have enough of, because I was not eating well either. I could not buy milk because a can of milk [infant formula] was $24 and I couldn’t afford that on a regular basis.

In terms of employment, proof of education and work references were difficult to provide to prospective employers. Women who hurriedly left their countries did not have the opportunity to gather the necessary papers. Even once in Canada, some women still faced barriers as their home country’s poor infrastructure did not allow them to retrieve these documents. Canadian work references often were demanded on applications. Respondents with higher education often had no more success in finding secure employment than others. As a university-educated women explains:

When I had just arrived, I enrolled into an integration course offered by Emploi-Québec. I had to bring my certificate to the Ministère de l’éducation for equivalence, and currently I am enrolled in a job search program… We are getting near the end of the course, yet I am not seeing any possibility of getting a job once I finish. So that’s really, really a big problem.

She had stated that her biggest issue in Canada was getting a job and that only upon arrival had she realized that it was very difficult to integrate into the job market. Regardless of legal status, the women who found employment tended to have temporary positions more vulnerable to layoffs, and experienced significant periods without any source of income. Several women chose to return to university or college with hopes of finding permanent work; this also provided them renewed hope as well as a new sense of identity. However, for women with young children, returning to school was difficult. Student loans and bursaries were not adequate to provide for a family’s needs, and family commitments did not allow them to supplement their income with paid employment.

Regardless of income or employment, most women experienced discrimination when seeking housing. They reported being refused apartments on the basis of ethnicity, language, immigration status, source of income and having children.

Every time I would call an advert[isement], I would call asking for a house and they would ask, “Oh, you have an accent. Where do you come from?” When I told them I am from Africa, well, the apartment was taken.

One respondent, clearly frustrated with the number of times a landlord had rejected her based on her accent, skin tone or country of origin, responded to yet another question of “Where are you from?” with “I am Canadian!” Some landlords were more subtle, citing lack of a Canadian credit or housing history as the reason for exclusion:

I had to go meet the landlord…to beg them that I am willing to pay 3 month’s rent in a block, to prove to them that I have the money. But I am having problems for landlords to trust me, that I am able to pay my rent so that they could give me the apartment.

Women with temporary immigration statuses reported being asked to pay more rent due to the possibility that they would be made to leave Canada before the end of the lease. One woman reported that she was asked to pay an entire year’s rent in advance. Lack of knowledge of their rights in relation to credit checks, advances on rent, apartment conditions and eviction policies made women vulnerable to exploitive situations. In addition, women with precarious immigration status found it difficult to secure a lease at all. Women not yet possessing legal status had little promise of secure housing.

Tipping Points Leading to Housing Insecurity

Apart from the pervasive challenges of unemployment, low income and lack of familiarity with the dominant culture and the local housing system, we discovered specific events often served as tipping points, incidents that forced women into less secure housing. The most common complications women shared were family crises and conflicts with landlords, neighbours or roommates.

Refugee women arrived in Canada having experienced significant levels of violence to themselves and/or close family members, often just prior to their arrival. The ongoing effects of trauma and loss compounded their difficulties in finding secure housing in a country that they had in no way prepared for, either physically or mentally. Other women experienced tragedy upon their arrival to Canada. One woman described staying with acquaintances in a crowded apartment immediately after arriving in Canada. She and her spouse were finally able to find work and save enough money to get their own apartment. Two weeks after moving into their own apartment, her husband complained of stomach pains and was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer before even becoming eligible for Quebec health insurance.Footnote 4 Her husband died shortly thereafter, leaving her solely responsible for their young child. She was not able to earn enough to maintain the apartment and slid into a series of precarious housing situations.

Landlords were the cause of tipping points in women’s trajectories when they took advantage of women housed in their apartments. Threatening to call the police or the provincial Rental Board was a tactic used by landlords to intimidate newcomer women, when often it was the landlords themselves who were breaking the law. In the following scenario, one of our respondents describes how the landlord not only threatened her when she asked for repairs, but also extracted money out of her. She described how, after going back and forth, “Finally I gave 200 dollars so that he would let me leave. He said that he would call the housing tribunal on me. He also said that he would send me to prison”. Another woman said that her landlord asked her to undress and sit in a bathtub of warm water so that he could take accurate measurements of the water’s temperature. After speaking with a community worker by phone, she refused and later moved out. She shared her vulnerability:

Me, I had a lot of fear. I am a woman that comes from Africa and I didn’t recognize that kind of behaviour. I didn’t know anything. I knew to pray, to prepare what was needed by men, to take care of my children…. That’s all. That’s all that I know.

Conflicts with neighbours also sometimes resulted in women losing secure housing. In this example, a woman’s neighbours called the police, and the landlord ultimately took her to the Rental Board. For a newly arrived immigrant unsure of her rights, this was described as a very stressful scenario:

They called the police and said I made noise because I played the piano… When I walk in my room, the neighbour will knock on my door and say, “I hear your footsteps,” so many times that I was just fed up with living there… At first I refused to leave and they went to the Rental Board, then later I agreed to leave, so we had an agreement that I will leave by myself.

When unable to find or afford their own apartments, women described having to share housing with relative strangers due to both their financial constraints and a lack of social networks. Such housing arrangements could end with very little notice and often on very unpleasant terms:

There is somebody I met from that particular place and I told him about my situation. And this person told me, “If ever you want to leave, I have a room. It is for my daughter but she no longer lives with me. You can have the room and be with me for a while until you find your own place.” And I lived with this so-called friend for one month, until he kicked me out of his house…Yes, he at first had compassion for me when I told him about my experience and all of that, but then on the way, the compassion he had for me wore out. I didn’t know anywhere else to go at the time because I was new here.

In other cases, previously positive space-sharing scenarios were terminated because of changing circumstances. After a brief stint of living on the streets, one respondent found an apartment to share with a woman whom she trusted and got along with well. A year later, the woman holding the lease was given short notice that her husband’s sponsorship application had been approved and that he would be moving to Canada. The respondent described her feelings when she had to vacate the shared apartment:

While I didn’t want to live with them as a couple, my roommate decided 1 day to kick me out saying her husband was coming the next day and she did not want us to share the space. I was very hurt because we had just renewed our lease together, and my budget was that I was going to spend the next coming year there… Her turning against me, that it was now me who was supposed to move out, and without giving me adequate notice, it was yet another setback reminding me of the chaos I had just lived a year prior to that time.

In some cases, the conflict with roommates was characterized by sexual exploitation. In this case, a storied echoed by other participants, a woman was forced to leave an apartment when she refused the sexual advances of the man holding the lease:

I asked him, “What about me? Where am I going to sleep?” He said, “We will stay here together.” I know in my culture, somebody who is not your husband, even if it is your own brother; you could not stay in the same room. So I told him that is a problem for me. So when I told him that, the following day I was going to church and he told me, “Give me my key.” He said, “Give me the key to the apartment.”

Unfortunately, even women living with family were subject to quick eviction decisions. Overcrowding, differences of values and interpersonal conflicts all played a part in the break-up of familial housing arrangements. One woman returned from a visit to her family back home to find the locks changed on her apartment; her husband alleged that she had abandoned her child. This led to a bout of homelessness and a painful and lengthy child custody dispute. Another woman describes how her pregnancy seemed to be the final straw in her living situation with her brother and sister-in-law:

When I became pregnant, I left them… My own brother kicked me out. Me, I wanted to remain and wait but they didn’t want me in their home anymore. It’s because there had always been disagreements between me and his wife. There were always tensions, and he supported his wife.

Despite facing such difficult crises, the women we met were also clear in their attempts to face and overcome their difficulties. They employed a wide range of strategies to avoid absolute homelessness.

Strategies to Avoid Absolute Homelessness

It was not unusual for women to have been dislocated several times since their arrival in Canada and to feel a constant sense of insecurity regarding their current housing situation. Most striking of all was the continuous movement among living arrangements. Even though at the time of interview, 11 newcomer women were living in apartments (private or subsidized), only two of the 26 women interviewed described their present living situation as stable. The entire housing experience was portrayed as very stressful for newcomers, who were often not aware of the usual process or their rights as tenants. Nevertheless, our interviews revealed that newcomer women used a wide spectrum of strategies to avoid absolute homeless. These included staying with family, couch surfing, using women’s or school residences, transitional housing, sharing a room, sharing an apartment, hotels, single rented rooms, and, in emergencies, locations such as an airport, train station, hospital waiting room or workplace. The reliance on social networks, community and social services and personal strengths were particularly important.

In terms of social networks helping participants avoid homelessness, women described positive examples of being housed with friends, relatives or with members of their ethnic community upon arriving in the city. For example, a mother of two children lived in a two-bedroom apartment with three other adults. Others described searching for live-in domestic or caregiving jobs as a way to secure housing. The live-in caregivers whom we interviewed did not want to remain in their employers’ homes (where the Live-in Caregiver Program requires they reside as a visa condition) (CIC 2014) on the weekends as they had found themselves being expected to work on their time off. Their solution was to rent a one-bedroom apartment that they shared with four to six other live-in caregivers each weekend. As noted above, these arrangements were often problem-laden, as crowded conditions, financial dependency, differing expectations and interpersonal conflicts made for stressful or exploitive relationships, which sometimes ended abruptly. Nonetheless, when it worked, it was better than the alternative.

Woven into the stories of most women were positive accounts of individuals or families that they had encountered due to cultural, familial or community connections. Oftentimes, they had been complete strangers just months before: one had been invited to live with the family of a college friend when she found she was pregnant, another received help finding an apartment after approaching a stranger whom she heard speaking her native tongue, and another’s ethnic community paid for the funeral arrangements of her husband. Refugees described how they encountered sympathetic taxi drivers or police who helped them find shelters.

Another source of support was community and government social services, although women were often unaware of the community and state services available to them. This is, in part, due to the fact that the women did not have the knowledge base to know where to begin looking and in part due to a lack of networking between the services themselves. However, several women referenced local organizations as having been helpful. These included agencies focused on refugee resettlement, early childhood intervention, pre and post natal services, food-clothing-furniture assistance, women’s issues and those directed to specific cultural groups.

Finally, personal attributes and strengths also kept women from experiencing absolute homelessness. We heard hope and determination in the women we spoke to: women whose strong cultural identity did not allow them to be defined by a temporary state of helplessness, women whose religious faith led them to believe that their suffering had a purpose, women who wanted their children to have a better life and women who identified personal strengths that allowed them to cope. For example, this newcomer woman avoided absolute homelessness in part through beliefs such as these that kept her from giving up:

In general, we, women of Africa, we have a strong character. Not everybody, but in general. And by nature, I am someone who fights, who isn’t apathetic… I try to move forward. I could say that on one hand, it’s because I believe in God, I trust myself to Him. It’s Him that made me get to where I am, but also my determination has helped me get here.

Discussion and Conclusion

While many of the efforts to address housing problems in general will also be of use to newcomer women, it is essential to take into account the ways in which their migration trajectory may influence their overall housing experience. Gender is a twin consideration in this equation. According to Citizenship and Immigration Canada in 2009, women were less likely to come as economic principal applicants than as Family Class applicants or the spouse or dependant of an economic applicant (Chiu 2011), which places women in “vulnerable situations where their sponsor (usually their spouse/partner or employer) has control over their immigration status (Bhuyan et al. 2014, p. 11). According to Paradis et al. (2008):

Women without status—whether they are temporary workers awaiting resolution of a refugee claim, or living “underground”—are extremely vulnerable, often living in conditions of deep poverty, housing instability, danger, and exploitation. They have limited access to social assistance, health care, and other social benefits, and often rely on under-the-table employment or informal networks to secure housing. (p. iii)

Further, women’s heightened dependencies (economic, relational, legal), linked with their heavier responsibilities for child rearing, make their experiences of housing insecurity different from men’s.

This study identified some recurring themes related to the improvement of policy and services for this population. While there are limits to the generalizability of our findings given the small sample and short timeline of this study, we have identified three main areas for development: (1) training on newcomer women’s needs for the two sectors most involved with this population: housing organizations and settlement services, (2) wrap-around services in terms of health, housing and immigration settlement and (3) transitional housing that caters to the specific needs of this population.

While recruiting participants for our study, we spoke with service providers in housing services who identified their own lack of expertise regarding other domains of policy such as immigration policy. Immigration settlement service providers—while responsible for helping immigrants and refugees with housing searches—were aware that they knew little of newcomers’ experiences once in housing. Thus, when women found themselves in substandard housing or without the means to pay their rent, there was little the settlement agencies could do. Both service organizations were interested in receiving training on these issues and were eager to increase communication and cooperation between them. This would be a first step towards wrap-around services for migrant women.

We also recognize that a significant, yet unknown, number of newcomer women facing poverty and homelessness do not come to the attention of either settlement or housing serving agencies. The challenges and concerns of these women are not adequately portrayed in this study. For the most part, they remain hidden and most vulnerable. The importance of ethno-cultural social networks in newcomer integration and settlement (Statistics Canada 2005) suggests a role for ethno-cultural communities and organizations in identifying this population and in preventing housing insecurity for newcomer women.

According to the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada (LSIC), approximately 40 % of newcomers encounter difficulties in finding housing—primarily related to high cost (Statistics Canada, 2005). Although statistics were not reported by gender in the LISC, newcomers report seeking housing assistance primarily from friends already settled in Canada, followed by relatives or household members and finally settlement organizations. Thus, immigration settlement agencies are an important site for the prevention of housing insecurity. We were struck by how many women expressed a sense of being lost when faced with a list of housing advertisements and a telephone. For women with limited social networks in the city, the lack of familiarity with neighbourhoods, housing and rental norms and prices—among other things—makes them ripe for exploitation and discrimination on the private housing market. Actual accompaniment in the housing search would have made a considerable difference in many women’s experience, helping them to avoid bad situations in the first place. Apart from the need for more housing services within immigration agencies, more resources are needed, such as settlement caseworkers who can assist women to identify and address their other needs in terms of health care, education and child care, for example.

Finally, newcomer women repeatedly told us “I had nowhere to go.” The women we interviewed often did not conform to the mandate of available shelters: absolute homelessness, or victims of domestic violence. Many were simply poor, socially isolated and dealing with multiple stressors. Access to longer-term transitional and supportive housing intended to support newcomers have been suggested for this population (Novac et al. 2009; Paradis et al. 2008) as a function of their many and complex vulnerabilities. We were, however, unable to locate models for transition shelter developed specifically to address the needs of this population. A model that seems appropriate is long-term transitional housing offered to young mothers (Cooper et al. 2009). It offers stability and security to women who find themselves in a difficult and unfamiliar situation, while offering them access to support services (e.g. education, employment training, trauma counselling) that can produce better outcomes. In the face of housing insecurity, transitional supportive housing for newcomers could assist in meeting other challenges immigrant women experience related to having their non-Canadian qualifications and job experience accepted in Canada and the need for language skills training (Chiu 2011). For many newcomer women with housing insecurity, having a year or more of such housing could interrupt the trajectory of dislocation and chronic need.

We conclude with the words of one of the women with whom we spoke, who articulated the reason she persevered through considerable hardship:

I have two girls, and what I went through I don’t want my daughters to go through… I won’t say I’m fighting for them. I’m trying to stand up on the right path because at the end of the day the future is all theirs. I’m just here to make a way for them.

Notes

Women participants contacted us directly after either seeing a poster or flyer about the study in a public place (drop-in centre, shelter, grocery store) or after being encouraged by a community worker to take part in the study. More than half of our respondents contacted us after seeing an announcement, although our impression is that the presence of these announcements in trusted locations encouraged their participation. We also believe that our sample leans towards women with more difficult housing experiences who would more easily self-identify as having experienced housing insecurity or homelessness.

Of course, the fact that our materials were available only in English and French would have limited the recruitment of people who do not speak one of three languages to referrals by a community group. We believe that people unable to speak French or English would have faced even greater housing risk that those we encountered.

New arrivals to Quebec, whether from elsewhere in Canada or from overseas, must wait 3 months before becoming eligible for Medicare.

References

Acosto, O., & Toro, P. (2001). Let’s ask the homeless people themselves: A needs assessment on a probability sample of adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(3), 343–366.

Anucha, U., Smylie, L., Mitchell, C., & Omorodion, F. (2007). Exits and returns: An explorator longitudinal study of homeless people in Windsor‐Essex County. Ottawa: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

Ben Soltane, S., Hanley, J., & Hordyk, S.-R. (2012). Révéler l’itinérance des femmes immigrantes à Montréal : documenter l’itinérance différemment. Montréal: Revue FéminÉtudes.

Bierman, A. S., Ahmad, F., & Mawani, F. N. (2009). Gender, migration and health. In V. Agnew (Ed.), Racialized migrant women in Canada: Essays on health, violence and equity (pp. 98–136). Toronto: UofT Press.

Bhuyan, R., Osborne, B. Zahraei, S., & Tarshis, S. (2014). Unprotected, unrecognized: Canadian Immigration Policy and violence against women, 2008–2013 Migrant Mothers Project, Policy Report, Fall 2014.

Boudarbat, B., & Gontero, S. I. (2008). Offre de travail des femmes mariées immigrantes au Canada. L’Actualité Économique, 84(2), 129–153.

Boulet, M. (2012). Le degré de déqualification professionnelle et son effet sur les revenus d’emploi des femmes immigrantes membres d’une minorité visible du Québec. Canadian Journal of Women and the Law, 24(1), 53–81.

Carter, T. S., & Osborne, J. (2009). Housing and neighbourhood challenges of refugee resettlement in declining inner city neighbourhoods: a Winnipeg case study. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 7(3), 308–327.

Carter, T. S., Polevychok, C., & Osborne, J. (2009). The role of housing and neighbourhood in the re‐settlement process: a case study of refugee households in Winnipeg. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 53(3), 305–322.

Chicha, M.-T. (2009). Le mirage de l’égalité: les immigrées hautement qualifiées à Montréal: Centre Métropolis du Québec.

Chiu, T. (2011). Immigrant women. Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2010001/article/11528-eng.htm#a3

Chiu, S., Redelmeier, D. A., Tolomiczenko, G., Kiss, A., & Hwang, S. W. (2009). The health of homeless immigrants. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63(11), 943–948.

CIC. (2014). Caregiver Program from http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/helpcentre/answer.asp?q=919andt=28

Conseil des Montréalaises. (2006). Les femmes et le logement à Montréal. Montréal: Conseil des Montréalaises.

Cooper, J., Walsh, C. A., & Smith, P. (2009). A part of the community: conceptualizing shelter design for young pregnant homeless women. Association for Research on Mothering Journal- Mothering and Poverty, 11(2), 122–133.

Creese, G., & Wiebe, B. (2012). ‘Survival employment’: gender and deskilling among African immigrants in Canada. International Migration, 50(5), 56–76.

D’Addario, S., Hiebert, D., & Sherrell, K. (2007). Restricted access: The role of social capital in mitigating absolute homelessness among immigrants and refugees in the GVRD. Refuge: Canada's Journal on Refugees, 24(1).

Danso, R. (2002). From ‘there’to ‘here’: an investigation of the initial settlement experiences of Ethiopian and Somali refugees in Toronto. GeoJournal, 56(1), 3–14.

Dion, K. L. (2001). Immigrants’ perceptions of housing discrimination in Toronto: The housing new Canadians project. The Journal of Social Issues, 57, 523–539.

Duchaine, G. (2013). Itinérance: les refuges pour femmes débordent, La Presse Retrieved from http://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/montreal/201310/11/01-4698770-itinerance-les-refuges-pour-femmes-debordent.php

Dye, J. F. Schatz, I. M., Rosenberg, B. A., & Coleman, S. T. (2000). Constant comparison method: A kaleidoscope of data. The Qualitative Report, 4(1/2). Retrieved from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR3-4/dye.html

Echenberg, H., & Jensen, H. (2008). Defining and enumerating homelessness in Canada. Ottawa: Parliament of Canada. Retrieved from http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/LOP/ResearchPublications/prb0830-e.htm.

Galabuzi, G.-E. (2006). Canada’s economic apartheid: The social exclusion of racialized groups in the new century: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Goldring, L., Berinstein, C., & Bernhard, J. K. (2009). Institutionalizing precarious migratory status in Canada. Citizenship Studies, 13(3), 239–265.

Hiebert, D. (2009). Newcomers in the Canadian housing market: a longitudinal study, 2001–2005. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 53(3), 268–287.

Hiebert, D., D’Addario, S., Sherrell, K., & Chan, S. (2005). The profile of absolute and relative homelessness among immigrants, refugees, and refugee claimants in the GVRD. MOSAIC.

Hiebert, D. J., Germain, A., Murdie, R., Preston, V., Renaud, J., Rose, D., . . . Murnaghan, A. M. (2006). The housing situation and needs of recent immigrants in the Montrèal, Toronto, and Vancouver. CMAs: An overview (pp. 8). Ottawa: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F. (1995). The active interview. Thousand Oaks: Sage Press.

Hordyk, S. R., Soltane, S. B., & Hanley, J. (2014). Sometimes you have to go under water to come up: a poetic, critical realist approach to documenting the voices of homeless immigrant women. Qualitative Social Work, 13(2), 203–220.

Ives, N., Hanley, J., Walsh, C. A., & Este, D. (2014). Transnational elements of newcomer women’s housing insecurity: remittances and social networks. Transnational Social Review, 4(2–3), 152–167.

Kazemipur, A., & Halli, S. S. (2001). The changing colour of poverty in Canada*. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie, 38(2), 217–238.

Kilbride, K. M., Webber, S. M., Wong, C., & Amaral, N. (2006). Plug them in and turn them on: Homelessness, immigrants and social capital. Ottawa: Housing and Homelessness Branch, Human Resources and Social Development Canada.

Kissoon, P. (2010). An uncertain home: Refugee protection, illegal immigration status, and their effects on migrants’ housing stability in Vancouver and Toronto. Canadian Issues (Fall), 8–15.

Klodawsky, F. (2006). Landscapes on the margins: gender and homelessness in Canada. Gender, Place & Culture, 13(4), 365–381.

Klodawsky, F., Aubry, T., Behnia, B., Nicholson, C., & Young, M. (2015). The panel study on homelessness: Secondary data analysis of responses of study participants whose country of origin is not Canada (p. 52). Ottawa: National Secretariat on Homelessness.

Kofman, E. (1999). Female ‘birds of passage’ a decade later: gender and immigration in the European Union. International Migration Review, 33(2), 269–299.

Ledent, J. (2012). Ethnicity and economic inequalities in Quebec: An overview. Montreal: INRS.

Leloup, X., & Zhu, N. (2006). Différence dans la qualité de logement: immigrants et non-immigrants à Montréal Toronto et Vancouver. Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l’integration et de la Migration Internationale, 7(2), 133–166.

Lombe, M., & Sherraden, M. (2008). Inclusion in the policy process: an agenda for participation of the marginalized. Journal of Policy Practice, 7(2), 199–213.

Montreal, City of. (2014). Portrait de l’itinérance: définition et chiffres. Retrieved from http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=8258,90439630and_dad=portaland_schema=PORTAL

Mosher, J. (2009). The complicity of the state in the intimate abuse of immigrant women. In V. Agnew (Ed.), Racialized migrant women in Canada: essays on health, violence and equity (pp. 41–69). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Moynihan, B., Gaboury, M. T., & Onken, K. J. (2008). Undocumented and unprotected immigrant women and children in harm’s way. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 4(3), 123–129.

MSSSQ, M. d. l. S. e. d. S. s. d. Q. (2008). L’itinérance au Québec. Cadre de référence La Direction des communications du ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec.

Murdie, R. A. (2008). Pathways to housing: the experiences of sponsored refugees and refugee claimants in accessing permanent housing in Toronto. Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l’integration et de la Migration Internationale, 9(1), 81–101.

Neufeld, A., Harrison, M. J., Stewart, M. J., Hughes, K. D., & Spitzer, D. (2002). Immigrant women: making connections to community resources for support in family caregiving. Qualitative Health Research, 12(6), 751–768.

Novac, S. (1996). No room of her own: A literature review on women and homelessness. Ottawa: Status of Women Canada.

Novac, S., Brown, J., & Bourbonnais, C. (2009). Transitional housing models in Canada: Options and outcomes. In: J. D. Hulchanski, P. Campsie, S. Chau, S. Hwang, E. Paradis (Eds.), Finding home: Policy options for addressing homelessness in Canada (e-book), Chapter 1.1. Toronto: Cities Centre, University of Toronto. www.homelesshub.ca/FindingHome

Paradis, E., Novac, S., Sarty, M., & Hulchanski, J. (2008). Better off in a shelter? A year of homelessness and housing among status immigrant, non-status migrant, and Canadian born families. Finding home: Policy options for addressing homelessness in Canada.

Preston, V. (2011). Precarious housing and hidden homelessness among refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants in the Toronto Metropolitan Area: CERIS.

Preston, V. Murdie, R., Wedlock, J., Agrawal, S., Anucha, U., D’ADDARIO, S., . . . Murnaghan, A. M. (2009). Immigrants and homelessness—at risk in Canada’s outer suburbs. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 53(3), 288–304.

Pruegger, V., & Tanasescu, A. (2007). Housing issues of immigrants and refugees in Calgary. Calgary: The City of Calgary, The Poverty Reduction Coalition, and the United Way of Calgary and Area.

Ray, B., & Preston, V. (2009). Are immigrants socially isolated? An assessment of neighbors and neighboring in Canadian cities. Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l’integration et de la Migration Internationale, 10(3), 217–244.

Ray, B., & Rose, D. (2011). How gender matters to immigration and settlement in Canada and US cities. In C. Teixeira, A. Kobayashi, & W. Li (Eds.), Immigrant geographies of North American cities (pp. 138–157). Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Rose, D. (2001). The housing situation of refugees in Montreal three years after arrival: the case of asylum seekers who obtained permanent residence. Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l’integration et de la Migration Internationale, 2(4), 493–529.

Rose, D., & Charrette, A. (2011). Pierre angulaire ou maillon faible? Le logement des réfugiés, demandeurs d’asile et immigrants à Montréal. Montréal: INRS et Immigration et métropoles.

Sjollema, S. D., Hordyk, S., Walsh, C. A., Hanley, J., & Ives, N. (2012). Found poetry–finding home: a qualitative study of homeless immigrant women. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 25(4), 205–217.

Statistics Canada (2005). Longitudinal survey of immigrants to Canada: A portrait of early settlement experiences. Minister of Industry, 2005. Catalogue no. 89-614-XIE

Stewart, A. (1998). The ethnographer’s method. Thousand Oaks: Sage Press.

Teixeira, C. (2009). New immigrant settlement in a mid‐sized city: a case study of housing barriers and coping strategies in Kelowna, British Columbia. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 53(3), 323–339.

Tischler, V., Rademeyer, A., & Vostanis, P. (2007). Mothers experiencing homelessness: mental health, support and social care needs. Health and Social Care in the Community, 15(3), 246–253.

Thurston, W. E., Clow, B., Este, D., Gordey, T., Haworth-Brockman, M., McCoy, L., . . . Carruthers, L. (2006). Immigrant women, family violence, and pathways out of homelessness: Prairie Women’s Health Centre of Excellence.

Thurston, W. E., Roy, A., Clow, B., Este, D., Gordey, T., Haworth-Brockman, M., . . . Carruthers, L. (2013). Pathways into and out of homelessness: Domestic violence and housing security for immigrant women. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 11(3), 278–298.

Vosko, L. F. (2006). Precarious employment: Understanding labour market insecurity in Canada: McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

Walsh, C. A., Ahosaari, K., Sellmer, S., & Rutherford, G. E. (2010a). Making meaning together: an exploratory study of therapeutic conversation between helping professionals and homeless shelter residents. The Qualitative Report, 15(4), 932–947.

Walsh, C. A., Beamer, K., Alexander, C., Shier, M., Loates, M., & Graham, J. R. (2010b). Listening to the silenced: informing homeless shelter design for women through investigation of site, situation, and service. Social Development Issues, 32(3), 35–49.

Walsh, C. A., Rutherford, G., & Kuzmak, N. (2009). Characteristics of home: Perspectives of women who are homeless. The Qualitative Report, 14(2), 299–317.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walsh, C.A., Hanley, J., Ives, N. et al. Exploring the Experiences of Newcomer Women with Insecure Housing in Montréal Canada. Int. Migration & Integration 17, 887–904 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0444-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0444-y