Abstract

This study analyzes how firms and workers respond to regulations limiting the use of temporary employment. In 2007, the Korean government introduced a labor market reform that required employers to convert a worker’s contract from a temporary to permanent one in order to continue to employ a worker for more than two years. From the perspective of employers, the new regulation can be thought of as a potential increase in firing costs for temporary workers after two years. Thus, employers have an incentive to improve the screening process to establish better matches and weed out bad matches prior to the increase in firing costs. From the perspective of workers, temporary workers have an incentive to provide greater effort after the policy change because the reform offers a potential path to permanent employment. My results show economically and statistically significant decreases in the probability of job separation in the first five months of tenure after the policy change, which implies that firms responded to the increased protection for temporary workers by improving their recruitment practices. However, based on observed overtime, I find no evidence supporting the view that temporary employees provided greater effort after the new regulation was put into effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Extensive literature exists on studies of the effect of employment protection legislationFootnote 1 (EPL) on labor markets. Prior studies (Bentolila and Dolado 1994; Blanchard and Landier 2002; Booth et al. 2002) focused on whether strict protection for workers had an impact on the level of unemployment and employment in European countries from the 1970s through the 1990s, but their findings were inconclusive.

In the 1980s, several European countries introduced labor market reforms that allowed new forms of employment, such as temporary contracts, fixed-term contracts, or hiring through temporary help agencies. These reforms were intended to relax existing labor market protection for specified classes of employment. Through the introduction of such alternative employment structure, policymakers hoped to increase labor market flexibility and lower unemployment. These reforms are usually called “two-tier” labor market policies or “partial” reforms because they tried to improve the flexibility “at the margin” of labor markets by easing restrictions on the use of temporary or fixed-term contracts, while still keeping strong protections for permanent workers (Bentolila and Dolado 1994; Blanchard and Landier 2002). Although such policies may have reduced rigidity in labor markets, they also encouraged firms to substitute temporary jobs for permanent ones. In fact, these reforms were associated with a surge of temporary jobs.Footnote 2

The extensive use of temporary jobs provoked a debate on whether they are stepping stones to better jobs, which may ensure increased job security and higher wages, or just dead-end jobs. In countries with fewer employment protection regulations such as the United States and the United Kingdom, temporary jobs seem to play a role as stepping stones to permanent jobs (Booth et al. 2002). In contrast, temporary jobs are less likely to function as stepping stones in the countries such as Spain where segmented labor markets result from rules providing strict protection for permanent jobs but few restrictions on temporary employment.Footnote 3 Amuedo-Dorantes (2000) suggested that temporary work in Spain is more likely to be a dead-end rather than a stepping stone to a permanent job, and argued that Spain’s experience could be generalized to other segmented labor markets.

Employment protection regulation in South Korea (below denoted simply as “Korea”) seems to follow the model of Spain and several other European countries. Since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, the Korean government has tried to increase flexibility in the labor market by allowing the extensive use of temporary jobs while keeping strict protection for permanent workers. As a result, the dual labor market structure solidified in the early 2000s, and the share of temporary employment in wage and salary workers almost doubled from 16.6% in 2001 to 29.4% in 2005 (Grubb et al. 2007). In addition, similar to Spain’s case, temporary employment in Korea seems not to function as a stepping stone since the transition rate from temporary to permanent employment over a one-year period was only 11.1% in Korea, while the transition rate in most European countries was above 50% (OECD 2013).

The drastic increase in temporary jobs has been pointed out as a main source of social inequality in Korea. Temporary jobs are usually characterized as inferior, as most temporary workers are paid less, are offered less training, and are less satisfied with their jobs (Booth et al. 2002). Thus, a steady increase in the proportion of temporary jobs could lower the welfare for workers and be a source of wage inequality. From workers’ perspectives, temporary workers hope to advance to permanent employment through temporary jobs, but they must endure poor labor conditions in the temporary jobs in terms of wages, working hours, and job security (D'Addio and Rosholm 2005).

Accordingly, the Korean government proposed a labor market reform in 2007 to lower the incidence of temporary jobs and to encourage employers to convert temporary contracts into permanent ones. The main policy change was to restrict the maximum duration of employment to two years in a job with a fixed-term contract. After the reform, an employer who employed a worker in a fixed-term contract for two years would need to convert the worker’s contract from a temporary to permanent one.

This study investigates employment dynamics after the policy change. It analyzes the effect of the stronger protection for temporary workers on job duration, and hence it is in line with the research by Boockmann and Hagen (2008) and Marinescu (2009) who examined a firm’s screening process using job duration data.

In this study, I describe in detail the policy change in the Korean labor market in 2007 first and then consider how firms and workers are expected to react to the policy change. According to the results of this study, the probability of job separation decreased in the first five months of tenure after the introduction of the new regulation, which suggests that firms reacted to the policy change by improving their recruitment, screening, and selection process. Firms’ better-hiring practices can result in better job matching, which can lower the probability of separation.

This study contributes to the understanding of the consequence of employment protection regulations in several ways. First, it provides evidence on a developed country in Asia that is characterized by a segmented labor market like that in Spain. Thus, we can verify whether Spain’s experience can be generalized to another country that has a similar labor market structure. Second, the 2007 reform in Korea offers an unusual policy change that increases protection for temporary workers, while previous empirical studies have focused on policy changes for permanent employment (Marinescu 2009) or the policies that made it easier for firms to create temporary jobs (Kahn 2007; Boockmann and Hagen 2008). Thus, the Korean case can give policymakers insight into the consequences of alternative policy options. Lastly, this study approaches the consequence of employment protection from the perspective of both firms and workers because the policy change is expected to induce behavioral changes of both firms and workers on fixed-term contracts. More specifically, it focuses on how changes in the maximum duration of fixed-term contracts affect job separations and the level of temporary workers’ effort, which was not analyzed simultaneously in previous literature.

2007 Labor Market Reform in Korea and its Possible Effects on Job Separation

Institutional Background of 2007 Reform in Korea

Between 1960 and the mid-1990s, Korea experienced rapid economic growth, and benefits from it seemed to be shared with workers through high job security and increased compensation (Sakong 1993). According to Kang and Yun (2008), the Korean economy experienced not only one of the highest growth rates in the world but also persistent declines in wage inequality from the 1980s through the mid-1990s.

However, as Korea’s economic growth slowed following the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, Korea’s high employment and income security for workers were pointed out as sources of inefficiency, and firms demanded a more flexible labor market environment. The Korean government responded to the demand by instituting a “two-tier policy” in the early 2000s that introduced new forms of employment,Footnote 4 while maintaining strong employment protection for permanent workers. Since then, workers on a fixed-term contract – a type of employment contract that terminates at a future date when a specific term expires or when a particular task is completed – accounted for a majority of the new forms of employment in Korea. However, the government did not place any restrictions on the use of fixed-term contracts in terms of the duration of contracts or repeated renewal of contracts until 2007.

As Lazear (1990) pointed out, employers have an incentive to evade the strict employment protection laws by hiring uncovered (temporary) workers. In most cases, Korean firms set the period of a fixed-term contract to less than one year to avoid offering severance pay, which is required by Korean labor law to be given to a worker who has been employed for one year or more.Footnote 5 Moreover, firms could renew the fixed-term contract many times with the worker’s agreement, which allowed them to not only continue employing the worker for several years, but also to terminate their employment without severance pay. Accordingly, many permanent jobs had been replaced with temporary ones in an attempt to reduce labor costs and increase employment flexibility.Footnote 6

As a result, the share of temporary employment in wage and salary workers almost doubled from 16.6% in 2001 to 29.4% in 2005 (Grubb et al. 2007), which solidified the dual labor market structure in Korea.Footnote 7 Recently, the high level of labor market dualism has been pointed out as one of the major factors responsible for rising income inequality, especially since temporary workers are paid about 60% as much as permanent workers (Jones and Urasawa 2012, 2014). Furthermore, wages of temporary workers are reduced because of their relatively short tenure, which ensures lower wages under the prevalent seniority-based wage systems in Korea (OECD 2016).

After five years of discussion with social partners and stakeholders, legislators proposed bills on temporary employment in November 2004 with the goal of lowering the incidence of temporary jobs and preventing firms from using fixed-term contracts as a long-term substitute for permanent workers. The legislation was passed two years later and implemented in 2007. A brief timeline for the legislation and application of the reform is provided in Fig. 1.

Although the legislation enacted several changes to labor market regulations, the primary goal was to restrict the length of fixed-term employment with one employer – including employment on successive fixed-term contracts – to a maximum of two years.Footnote 8 More specifically, after the reform, if an employer chose to continue to employ a worker for more than two years, then the employer had to convert the worker’s contract from a fixed-term to a permanent one.Footnote 9 Of course, employers still had the option to dismiss a worker employed for less than two years on a fixed-term contract with no severance costs by simply not renewing the contract. However, if the worker was still on the job at the end of the two-year period, the fixed-term contract would be regarded as a permanent contract. The reform took effect in July 2007, and hence any fixed-term contracts signed from July 2007 onward became subject to the new regulation.

The Possible Effects of the 2007 Reform on the Termination of Employment

Firms’ Behavioral Change

Before the policy change, firms that hired workers on fixed-term contracts had three choices twenty-four months after first hiring a worker on a fixed-term contract: (i) Continue to employ the worker by converting the contract from fixed-term to permanent, (ii) Continue to employ the worker by offering another fixed-term contract, (iii) Dismiss the worker and possibly replace him or her with a new employee. However, since the firms’ second option – continue to employ the worker under a fixed-term contract – was no longer available after the 2007 reform, firms had to consider alternatives among the other options – (i) and (iii) – depending on the type of job that was filled under the fixed-term employment arrangement (Fig. 2 summarizes the change in a firm’s choice before and after the reform). Here, jobs can be classified according to whether or not they involve accumulation of firm-specific human capital.

If firm-specific human capital can be accumulated through working on a job, and the employer values it (Job type I), then the firm that would have chosen option (ii) may be incentivized to choose option (i) after the reform. In this case, firms valuing the accumulation of firm-specific human capital face a discontinuous increase in firing costs after 24 months of employment. Thus, they have an incentive to improve their screening process to establish better job matches and weed out bad matches. To this end, firms can change their human resource management practices in two ways. First, at the various stages of the recruitment process, firms can exert greater effort to establish better job matches. For example, they may require stricter qualifications for a job, review job applications more thoroughly, or filter candidates through more in-depth interviews and thus improve the quality of job matches. Even though the quality of job matches is difficult to quantify, the result of the change in the quality can be captured by the change in the probability of job separation. Thus, better recruitment practices and higher match quality could cause a decrease in the probability of employment termination – a recruitment channel (H1). The decrease in the probability is expected to be more prominent at very low tenures because most separations from jobs happen in the early stages of working (Marinescu 2009). Second, firms can exert greater effort in their monitoring and evaluation process to weed out bad matches before the increase in firing costs. Through higher monitoring efforts and rigorous evaluations, the match quality of the remaining jobs may be improved. Thus, the result can be represented statistically as an increase in the probability of job separation before 24 months of tenure. Furthermore, since it is better, in the view of human capital accumulation, to identify bad matches as early as possible and replace unproductive workers with new ones, the increase in the probability is more likely to be observed in the early stages of employment – a monitoring channel (H2).

On the other hand, if a job is simple, and working on it accumulates little specific human capital (Job type II), then firms that have filled the simple job with a temporary worker can replace the worker with another temporary one easily. Then, the firm’s best choice after the reform is to initially hire a worker on a fixed-term contract for a period of less than a year, renew that contract, and then dismiss the worker right before his/her tenure reaches 24 months, after which firing costs increase discontinuously. In this case, even though firms may not experience the new employment regulation as an increase in firing costs, their reaction to the regulation could change the probability of job separation. More specifically, job separation hazards may increase right before 24 months of workers’ tenure after the reform – a replacement channel (H3).

Based on the reasoning so far, I suggest three hypotheses on how the reform influences firm behavior and what changes in the hazards of employment termination are expected after the reform. A summary of the possible effects of the reform is suggested in Fig. 2. In the first part of the empirical analysis, this study investigates evidence that supports each hypothesis using statistical models. In the recruitment (H1) and monitoring (H2) channels, the direction of changes in termination hazards is the opposite. Thus, if I can observe either an increase or a decrease in the termination hazards at low tenures, I can tell which hypothesis dominates the other. In addition, the replacement effect (H3) can be easily verified by looking at the change in the hazards around 24 months.

Workers’ Behavioral Change

Workers’ effort in their jobs could be considered an important factor when their employers decide which worker should be kept or weeded out (Booth et al. 2002). Because the new regulation requires employers to convert a fixed-term contract to a permanent one when tenure with the employer exceeds two years, workers in fixed-term employment have an incentive to exert greater effort in their job to achieve advancement to permanent employment, which usually offers higher job security and compensation. Putting greater effort into a job may include enduring harsh working conditions, complying with excessive requests from their employer or boss without reasonable compensation, or working overtime voluntarily. If many workers on fixed-term contracts prefer permanent employment and expect the chance of getting converted to permanent employment to be relatively high after the reform, then their higher effort in their jobs could be expressed statistically as a decrease in the termination hazards throughout the duration of fixed-term employment – a worker’s effort channel (H4). Thus, when I investigate the consequence of a new employment regulation, the response of employers as well as employees should be considered. Accordingly, the last hypothesis (H4) is added to the possible effects of the reform from the perspective of workers.

In the second part of the analysis, this study seeks to find empirical evidence that supports the view that workers on fixed-term contracts exert greater effort after the reform. Although it is difficult to measure workers’ effort, changes in the level of their efforts could be investigated by using a proxy variable. To date, few studies on workers’ effort have been conducted in economics, but two studies used similar variables to proxy the level of workers’ effort. First, Booth et al. (2002) used the number of weekly unpaid overtime hours to proxy the effort and showed that high effort increases the probability of exiting from temporary employment only for women. Second, Engellandt and Riphahn (2005) used a binary variable – whether a worker provides unpaid overtime hours or not – as a proxy for workers’ effort levels and confirmed workers on temporary contracts exert significantly greater effort than permanent workers in Switzerland. Following these studies, I use the information on workers’ overtime work to proxy the level of effort.

Analysis I: Firm’s Behavioral Change after the Reform

In the first empirical analysis, this study investigates the effect of the 2007 Korean reform on the probability (or hazard) of employment termination. Through the analysis, I seek to examine how firms’ reactions to the reform are reflected in the changes in employment termination hazards.Footnote 10

Data Set and Sample

To investigate the impact of the 2007 Korean reform on the labor market, this study uses the Korean Labor & Income Panel Study (KLIPS).Footnote 11 The KLIPS consists of three data sets, for households, individuals, and job histories. The job history data are composed of observations of jobs (rather than individuals) and contain information on the jobs held by individuals who were surveyed between January 1998 and August 2016. The data offer information on the jobs such as the date at which a job began or terminated (if the job ends before an interview), interview date, type of employment (regular, temporary-contract, or casual), and other job characteristics (occupation, industry, firm size, sector, average hours of regular or overtime work, wages, etc.). Although KLIPS is a yearly survey that began in 1998, it also asks every interviewee about his/her job history since entering the labor market. Thus, it contains the full records of job history for all respondents. Furthermore, an in-depth analysis is possible when the job history data are combined with the data set of KLIPS for individuals that contains workers’ characteristics such as gender, age, education level, marital status, and the area of residence.

Fixed-term employees regulated by the 2007 Korean reform are defined as the workers whose contracts end on a specified date or when a specific task is completed; temporary-contract employees according to the classification of KLIPSFootnote 12 cover workers whose employment contracts are at least one month and less than one year. Thus, temporary-contract employees are a subset of fixed-term employees. In the Korean labor market, however, most fixed-term employees are on temporary-contracts because firms set the period of the fixed-term contract to less than one year to avoid offering severance pay, which is required by Korean labor law for contracts of one year or more. Thus, only observations classified as jobs that began with temporary-contracts in KLIPS data are selected for the sample to analyze the effect of the reform.

The dependent variable (r), which is the tenure of a job in months, is measured by the duration in months from job start date to job end date if a job is terminated before the interview. Where a job is still in progress at the last interview date, the dependent variable is measured by the time from the job start date to the last interview date and the case is coded as right-censored.

The sample includes only jobs that began from January 2001 and onward. Since the Korean economy had experienced the Asian financial crisis in 1998, the effect of which persisted for several years, the early years of the survey were still affected by the crisis. To prevent the experience of the crisis from influencing the results of this study, the jobs that began before January 2001 are excluded from the analysis. Thus, the final sample includes only the jobs beginning under temporary-contracts that span the period between January 2001 and August 2016.

Lastly, the sample is divided into two parts, a control group – jobs that began before the reform – and a treatment group – jobs that began after the reform. In addition, jobs in the control group that continue beyond the effective date of the regulation (July 2007) are treated as being censored at the reform’s effective date in order to exclude the possibility that the jobs in the control group could also be affected by the introduction of the new regulation and to estimate precisely the change in the termination hazard caused by the reform. Thus, the analysis examines whether the termination hazards of temporary-contract employment differ significantly for the control and treatment groups. Figure 3 shows an example of jobs in the control and treatment groups.

Empirical Strategy

As a first step, I estimate the hazard function h(r) for the control and treatment groups using the nonparametric method suggested by Kaplan and Meier. The hazard function for a job is the limiting probability that employment termination occurs right after the tenure of r conditional on the job having lasted until r:

The Kaplan–Meier estimate of the hazard function can be represented by (Eq. 2) where nr is the number of jobs at risk at r, and fr is the number of jobs terminating at r.Footnote 13

First, jobs under temporary-contracts are divided into the control and treatment groups, and the basic statistics for each group are presented in Table 1. Although jobs in the control group began earlier than those in the treatment group, the median value of job tenure is lower for the jobs in the control group since the jobs are treated as being censored at July 2007. In addition, the treatment group has more jobs since the post-reform period is longer than the pre-reform period. However, the proportion of failure and censored cases are almost the same in the control and treatment groups.

Second, the hazard functions for each group are nonparametrically estimated using (Eq. 2). The detailed hazard table is provided in the Appendix (Table 6). Figure 4 shows the nonparametrically estimated hazard functions for the control and treatment groups visually using the estimates (h(r)) in Table 6. For jobs that started before the reform (the control group), the hazards of employment termination increase drastically at first having a peak at three months, and then decline overall,Footnote 14 although they show some fluctuation across tenure, and have another peak around twenty-five months. However, the shape of the hazard function for the treatment group is different from that for the control group. The termination hazard for the treatment group increases at first, peaks at thirteen months, and declines gradually with some fluctuation. The main difference in the hazard functions can be found in the first eleven months of tenure. The hazard function of the treatment group is much lower than that of the control group in the early portion of the job spells implying that the probability of employment termination decreases substantially for that period.

Figure 5 provides the difference of the hazard rates between the control and treatment group at each month of tenure. It shows large decreases in the hazards in the first eleven months and at twenty-five months after the reform; decreases are relatively large between two to five months. However, the difference is about as likely to be positive as negative after thirteen months. Thus, the main concern of this study is whether the difference in the two hazard functions remains significantly different even after controlling for other variables relevant to the employment. To verify this, I estimate the following probit modelFootnote 15:

-

Probit Model

Posit an unobserved latent variable, \({Y}_{it}^{*}\), for individual i in a job lasting at least t, as

The observed variable, \({Y}_{it}=1\left\{{Y}_{it}^{*}\ge 0\right\}\)

Here, \({Y}_{it}\) is a dummy variable indicating whether a job i terminated at t. \({Post-job}_{i}\) represents a treatment effect that has a value of one when a job began after the reform (July 2007), and \({D}_{rit}\) is a dummy identifying month of tenure (r) for a job.Footnote 16 The coefficient, \({\delta }_{r}\), of the interaction term captures the effect of the reform on hazards of employment termination at each month of tenure (r). In the model, the error term, \({\varepsilon }_{it}\), is assumed to follow a normal distribution.

The variable \({X}_{it}\) is a set of controls including worker characteristics (gender, marital status, education level, and age), job characteristics (firm size, occupation, industry, and union membership), and a constant. The number of previous jobs for a worker is also included in the model to control for worker heterogeneity.Footnote 17 In addition, in order to control for the macroeconomic conditions upon job separation, I tested various unemployment rates of the previous months, and the average unemployment rate over the last three months gives the most statistically significant result.Footnote 18 A detailed explanation on the control variables can be found in the Appendix (Table 7).

Results

The full results from the probit analysis are provided in the Appendix (Table 7), and Table 2 collects only the estimates for the coefficient, \({\delta }_{r}\), of the interaction term, which captures the effect of the reform on the hazard of employment termination at each month of tenure (r).

The first section (No Control) of Table 2 provides the results from probit analysis without controlling for the covariates except for \({D}_{rit}\), \({Post\ job}_{i}\), and the interaction terms. The results are similar to the difference in the hazard functions suggested in Fig. 5. The results from the analysis controlling for the covariates are suggested in the second section (Control).

The three right columns contain the results estimated by using subsamples, considering the exceptions of the regulation. The legislation allows exceptions in the application of two-year maximum duration of fixed-term employment, and the three subsamples in Table 2 exclude exceptional cases that can be identifiable in the data set: (i) firms in the private sector with fewer than five employees, (ii) workers aged 55 or older at the beginning of a job, (iii) workers who work less than 15 hour per week regularly.Footnote 19 Although the sample size decreases by 45% after taking the exceptions (i)-(iii) into account, the results do not change much except that statistical significance of coefficients increase at twelve and twenty-seven months of tenure.Footnote 20

The results can be interpreted as follows: First, even after controlling for covariates, the effect of the reform is still statistically significant in the first five months of tenure. The decrease in the hazards at tenure of less than six months could be evidence supporting the first hypothesis, (H1) recruitment channel, or could be interpreted as the recruitment effect of (H1) dominates the monitoring effect of (H2). Second, job separation hazards do not increase right before 24 months of tenure after the reform, which is contrary to the (H3) replacement effect. Thus, the third hypothesis, (H3) replacement effect, cannot be accepted, and the reform seems not to influence the termination hazards through the replacement channel– the replacement of a worker on fixed-term contract with another one. In conclusion, the results support the effect of the reform on the hazards of job termination only through (H1) Recruitment channel.

Figure 6 shows visually the average marginal effects (AMEs) for the interaction term (\({D}_{rit}\bullet {Post\ job}_{i}\)) across tenure. Through the comparison of the estimates, it can be confirmed that the AME from the probit analysis without controlling for the covariates (No Control) is similar to the difference in Kaplan–Meier hazard estimates in Fig. 5 in terms of the shape of the hazard function. Moreover, although the effect of the reform becomes slightly smaller after controlling for the covariates, it is still statistically significant in the first five months of tenure.

In summary, the probability of job separation decreases in the first five months of tenure after the reform, which is consistent with the recruitment channel that firms react to the policy change by improving their recruitment process. Firms’ better recruitment practices can result in well-matched jobs, which can lower the separation probability in several ways: workers with well-matched jobs have less incentive to search for alternative jobs, and they are also less likely to accept outside job offers (Jovanovic 1979b); we also expect that better-matched workers are less likely to be terminated.

Alba-Ramirez (1998) suggested the reasons why firms use temporary employment contracts: first, they use temporary workers to perform temporary work or to avoid the employment rigidity of a permanent contract; second, a temporary contract can also be used as a screening device. In the Korean labor market, temporary jobs have been used mainly as a long-term substitute for permanent ones to reduce labor costs and increase employment flexibility. In addition, the reform seems to reinforce a screening function of temporary contracts in the Korean labor market, which leads to better-matched jobs.

Sensitivity Tests

I perform sensitivity tests to examine how estimates of the effect change if an alternative definition of the sample period is used for the same probit model. First, in the full sample period (2001–2016), the post-reform period is longer than the pre-reform period. To balance the sample periods before and after the reform, I use shorter but balanced sample periods, ① 2001–2013 and ② 2004–2010, instead of the full sample period, and the results are provided in the Appendix (Table 8). When the shorter balanced sample periods are used, the effect of the reform is still statistically significant in the first five months of tenure, although the point estimates for months seventeen and twenty are statistically significant.

Second, as the legislation was passed in November 2006 and then implemented in July 2007, it is possible that firms and workers may have anticipated the policy change and adjusted to the new regulation prior to its implementation. Because fixed-term contracts signed from July 2007 onward are subject to the new regulation, jobs that were created right before and after the implementation could be affected by the anticipation. For example, firms could hire more workers on the fixed-term contracts prior to the implementation and, conversely, workers might want to postpone the start of their work on fixed-term contract employment until July 2007. I perform the second sensitivity test to examine how estimates of the effect change if a period of adjustment (① November 2006 – December 2007 or ② July 2006 – June 2008) is excluded from the sample. The results are not affected by this alternative definition of the sample period, which suggests that anticipation or delays in the reaction to the policy change do not play a significant role in determining the estimates of the impact of the policy change on the job termination hazard.

In the last sensitivity test, I examine if the global recession during 2008–2010 affects the job separation hazards. Since the treatment group includes the global recession period while the control group does not, the temporary-contract workers in the treatment group could have been more carefully hired during the recession period, which could result in different termination trends between the temporary-contract workers in the treatment and control groups. Basically, the monthly unemployment rate was already controlled in the main analysis in order to capture the impact of the macroeconomic changes on job separation.Footnote 21 In addition, I estimate the same probit model after excluding the various global recession periods (① January – December 2009, ② January 2008 – December 2010, or ③ January 2007 – December 2011). As provided in the last section of Table 8, the results do not change significantly in the first five months of tenure even when the recession periods are excluded, which suggests that the global recession had little impact on the job separation hazards of temporary-contract employment in Korea.

Placebo Tests

I perform placebo tests to see how the results look with false reforms, and the results are provided in the Appendix (Table 9). In the first placebo test, I code the data as if the reform occurred in ① January 2004 or ② January 2013 (instead of the actual reform in July 2007)Footnote 22 and estimate the effects of the two false reforms with the same probit model. The results show no statistically significant effect of the false reforms in the first five months of tenure, except for a point estimate at five months of tenure when the false reform is set in January 2013.

In the second placebo test, I code the data as if there was a reform affecting permanent workers– those not subject to the regulation – instead of temporary workers and estimate the effect of the false reform with the same probit model. To identify permanent workers in the data set, I select regular workers who were provided with social insurance by their employers, since they can be thought of as the most protected workers in the Korean labor market. Social insurance in Korea includes unemployment insurance, national pension coverage, national health insurance, and industrial accident compensation insurance. The results show no statistically significant effect of the false reform on permanent workers in the first five months of tenure, although positive effects of the false reform are found in month twenty and later months of tenure.

As neither placebo test finds the effect of the false reforms in the first five months of tenure, these results support the view that the actual reform in July 2007 has a causal effect on termination hazards in the early stages of temporary employment.

Analysis II: Workers’ Behavioral Change after the Reform

The goal of the second analysis is to test the last hypothesis, (H4). The analysis seeks to find empirical evidence which supports the view that workers on temporary-contracts provide greater effort after the reform to obtain advancement to permanent employment. If the evidence supports this view, it can be argued that the reform also influences the hazards of employment termination through the channel of workers’ effort, which results in decreases in the exit hazard. However, it is difficult to measure the level of workers’ effort quantitatively. Thus, this study follows previous studies, Booth et al. (2002) and Engellandt and Riphahn (2005), which use the information on workers’ overtime as a proxy for workers’ effort.Footnote 23

Data Set and Sample

This study compares the effort levels of temporary-contract workers – those subject to the regulation – and permanent workers – those not subject to the regulation. I use the KLIPS data for individuals and the final sample consists of selected regular workersFootnote 24 and temporary-contract workers.

The survey offers various information on working hours of wage and salary workers – for example, regular working hours per week, whether a worker provides overtime hours, the average of weekly (or monthly) overtime hours, and whether the overtime hours are paid or unpaid. Using this information, four dependent variables – two binary variables and two continuous variables – are derived to proxy workers’ efforts (see Table 3). The binary variables – OTit and UOTit – indicate whether a worker provides overtime hours or not (OTit includes both paid and unpaid overtime; UOTit denotes unpaid overtime). The second two continuous variables – HRit and UHRit – stand for how many hours of overtime a worker provides on average per week (HRit includes both paid and unpaid overtime hours; UHRit denotes the hours of unpaid overtime).

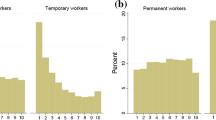

Descriptive statistics for each dependent variable are provided in the Appendix (Tables 10 and 11) in detail. Table 4 provides the proportion of the regular or temporary-contract workers who provide overtime hours.

First, the proportion of regular workers who work overtime (\({OT}_{it}=1\)) is much higher than that of temporary-contract workers. The proportion for regular workers fluctuated around 38%, but that for temporary-contract workers seemed to decrease over time. In addition, the difference in the proportions (\(\Delta {OT}_{t}\)) decreased slightly until 2007, but it showed small increases thereafter. Second, similar patterns are found in the proportion of employees who work unpaid overtime (\({UOT}_{it}=1\)). The proportion of workers who work overtime without financial compensation was nearly three times higher for regular workers in the early survey years. However, the differences in the proportions (\(\Delta {UOT}_{t}\)) became larger in later years due to the decrease in unpaid overtime for temporary-contract employees. Third, the two differences – for both overtime (\({\Delta OT}_{it}\)) and unpaid overtime (\({\Delta UOT}_{it}\)) – in the proportions between regular and temporary-contract workers fluctuated relatively less during the pre-reform period (2001 – 2006), and the gaps seemed to become larger after the reform. This suggests that the proportions for the temporary-contract workers evolved in a similar way as the proportions for the regular workers during the pre-reform period.

Based on the finding, this study applies a difference-in-differences approachFootnote 25 to the analysis for workers’ effort. In the setting, the control and treatment groups are composed of regular workers and temporary-contract workers respectively because only the temporary-contracts – which are signed from July 2007 and onward – are subject to the new regulation, and there was no significant change in regulations on permanent contracts during the analysis period that would directly influence working hours.

Empirical Strategy

In order to examine whether workers on temporary-contracts (\({Temp}_{it}=1)\) show greater effort after the reform, observations in the sample are divided into three groups. Group 1 includes workers who were surveyed before the reform (\({After}_{t}=0)\); hence, their jobs had to begin before the reform \(({Post\ job}_{it}=0)\). Group 2 consists of workers who started their jobs before the reform \(({Post\ job}_{it}=0)\) but were surveyed after the reform (\({After}_{t}=1)\). Group 3 has workers whose jobs began after the reform \(({Post\ job}_{it}=1)\); hence, they had to be surveyed after the reform (\({After}_{t}=1)\). Figure 7 describes the three groups visually.

Although only temporary-contract workers in Group 3 were subject to the new regulation initially, I test whether the reform influenced the effort levels of temporary-contract workers in Group 2 as well as Group 3. To this end, two econometric models – (Eq. 4) and (Eq. 5) – are employed based on a difference-in-differences approach.

-

Probit Model

An unobserved latent variable, \({Y}_{it}^{*}\), is assumed to be predicted as follows:

The observed variable, \({Y}_{it}=1\{{Y}_{it}^{*}\ge 0\)}, \(where {Y}_{it}= {OT}_{it}\mathrm{ or }{UOT}_{it}\)

In the specification of the models, two interaction terms – ‘\({Temp}_{it}\bullet {After}_{t}\)’ and ‘\({Temp}_{it}\bullet {Post\ job}_{it}\)’ – are included to examine the two types of treatment effects. The coefficient, \({\beta }_{4}\), of the first interaction term captures the first treatment effect – whether the temporary-contract employees in the Group 2 provide greater effort after the reform relative to the regular workers (\({\beta }_{4}={Diff}_{2}-{Diff}_{1}\)). The coefficient, \({\beta }_{5}\), of the second interaction term compares the effort levels of the temporary-contract workers in Groups 2 and 3. Thus, \({\beta }_{5}\) captures the additional treatment effect for the observations that were surveyed after the reform, where a job contract was also made after the reform (\({\beta }_{5}={Diff}_{3}-{Diff}_{2}\)).

This model implies a probit model for the binary dependent variables (OTit and UOTit); for the continuous dependent variables (HRit and UHRit), a Tobit model is used to deal with the censoring issue. In both models, the error term, \({\varepsilon }_{it}\), is assumed to follow a normal distribution.

-

Tobit Model

An unobserved latent variable, \({Y}_{it}^{*}\):

The observed variable, \({Y}_{it}=\mathrm{max}\{0, {Y}_{it}^{*}\}\), \(where {Y}_{it}={HR}_{it}\) or \({UHR}_{it}\)

In the models, the variable Xit is a set of controls including worker characteristics (gender, marital status, education level, age, and tenure) and job characteristics (sector, union membership, firm size, occupation, and industry). Moreover, in order to capture the time effect and the macroeconomic conditions in the survey year, a linear time trend and its square term, employment rates, and unemployment rates are controlled. A detailed explanation on the control variables can be found in the Appendix (Table 12).

Results

Full results estimated by the probit and tobit models are provided in the Appendix (Table 12). Table 5 contains only the four coefficients of interest and the conditional average marginal effects. The two sections, (1) and (2), show the results for the binary dependent variables, \({OT}_{it}\) and \({UOT}_{it}\). First, temporary-contract workers (\(Temp\)) are less likely to work overtime and unpaid overtime compared to regular workers.Footnote 26 The estimated average marginal effect implies an 11 percentage point difference in overtime work and 3.9 percentage point difference in unpaid overtime work.Footnote 27 Second, the likelihood that regular workers work overtime increased by 3.3 percentage points in the period of post-reform (\(After\)), but there is no statistically significant increase in the likelihood of unpaid overtime. Third, whether a job contract was made before or after the reform (\(Post\ job\)) has a statistically significant impact on neither overtime or unpaid overtime work for regular workers. Fourth, temporary-contract workers in Group 2 seem not to work more overtime or unpaid overtime after the reform (\(Temp\bullet After\)) compared to regular workers. Fifth, there is also no statistically significant difference in the likelihood of providing overtime or unpaid overtime work between the temporary-contract workers in Groups 2 and 3 (\(Temp\bullet Post\ job\)). In sum, I cannot find any evidence that temporary-contract workers are more likely to work overtime or unpaid overtime after the reform compared to regular workers.

The last two sections, (3) and (4), provide the results for workers’ average weekly overtime and unpaid overtime hours, \({HR}_{it}\) and \({UHR}_{it}\), which were estimated with a Tobit model. The results are similar to those in the first two columns. First, temporary-contract workers are likely to provide fewer overtime and unpaid overtime hours than regular workers: temporary-contract employees work about 4.7 fewer hours overtime and about 3.1 fewer unpaid hours overtime in a week than regular workers. Second, regular workers work overtime about 1.4 h more in a week after the reform, but there is not a statistically significant increase in the hours of unpaid overtime. Third, for regular workers, the average weekly hours of overtime and unpaid overtime seem not to depend on whether a job contract was entered into before or after the introduction of the new regulation. Fourth, for the temporary-contract workers in Group 2 and Group 3, the reform has no significant impact on the average weekly hours of overtime and unpaid overtime.

In summary, the results do not support the view that temporary-contract workers work overtime more after the reform relative to permanent workers (or selected regular workers). If workers’ effort levels in their jobs are captured by overtime work (or the hours of overtime work), then the results do not suggest any evidence that supports the last hypothesis (H4) – workers on temporary-contract provide greater effort after the reform. Hence, there is no evidence that greater worker effort produces the decrease in the hazards of employment termination that I observe in the first five months on the job. Thus, the hypothesis (H4) is not supported, and I conclude that there is no change in the hazards of employment termination through the channel of workers’ effort.

Conclusion

This study analyzes how firms and workers respond to increased protection for temporary employment. In 2007, the Korean government introduced a new regulation that restricts the length of fixed-term employment with an employer to a maximum of two years. After the policy change, an employer who employed a worker in a fixed-term contract for two years would need to convert the worker’s contract from a fixed-term to a permanent one.

First, from the perspective of employers, the new regulation can be thought of as a potential increase in firing costs for temporary workers. Thus, the employers may try to improve the screening process to establish better matches and weed out bad matches prior to the increase in firing costs, which results in better job match quality. In order to test hypotheses on firms’ behavioral change, this study employs survival analysis that investigates the change in the probability of employment termination after the reform. The results show statistically significant decreases in the probability of job separation in the first five months of tenure after the policy change, which implies that firms respond to the strict protection for temporary workers by improving their recruitment practices.

Second, temporary workers have an incentive to provide greater effort after the policy change because the reform offers a potential path to permanent employment that ensures higher job security and compensation. Moreover, the greater effort in their jobs can result in a decrease in the probability of employment termination. This study uses information on workers’ overtime as a proxy for workers’ effort since it is difficult to measure the level of workers’ effort. However, the results provide no evidence supporting the view that temporary employees are more likely to work overtime after the policy change. Thus, if workers’ effort levels in their jobs are captured by overtime work, our results do not confirm the hypothesis that strict protection for temporary workers can decrease the probability of employment termination through the increase in the level of workers’ effort.

In conclusion, the results suggest that the increased protection for temporary workers could improve the firm’s recruitment process. In the Korean labor market, temporary jobs in the Korean labor market have been used mainly as a long-term substitute for permanent ones to reduce labor costs and increase employment flexibility. In addition, the reform seems to reinforce a screening function of temporary contracts in the Korean labor market, which leads to better-matched jobs.

This study approaches the consequence of employment protection from the perspective of both firms and workers because the policy change is expected to induce behavioral changes in both firms and workers on fixed-term contracts. In particular, it used the information on workers’ overtime work to proxy the level of effort. However, if unpaid or paid overtime work is not enough to capture workers’ effort level, firms’ better recruitment efforts may not be distinguished from workers’ efforts. Therefore, future studies should find better ways to decompose the total effects of the reform clearly into two parts that are caused by behavioral changes of firms and workers respectively.

Notes

Employment protection legislation (EPL) includes labor market policies and institutions that regulate or constrain a firm’s hiring and firing behaviors. OECD (2004) refers to EPL as the multidimensional regulations that influence a firm’s behavior in terms of human resource management. EPL may not only be in the form of law, but could also result from court rulings or collective bargaining between management and worker groups.

As pointed out in Lee’s (1996) study, the surge in temporary employment could be attributed to not only changes in labor market policy that protect permanent workers from the market adjustment, but also changes in the economic environment (e.g., technological progress and the rapid integration of trade markets).

The segmented labor market consists of core and peripheral sectors: the core sector is filled with permanent jobs that provide high job security and good compensation while jobs in a peripheral sector are characterized by bad working conditions, low job security, and low wages.

The new forms of employment include workers on fixed-term contracts, temporary agency workers, dispatched workers, and atypical workers who are classified as self-employed by labor law but still have many of the characteristics of being employees.

In Korea, severance pay is based on years of service with a company on a specific contract, and at least one month’s wages are provided to the worker for each full year of employment. Firms must offer the severance pay to any salary and wage worker who has worked for one year or more under a specific employment contract.

A Korean government survey showed that 32.1% of firms cited reducing labor costs and 30.3% cited increasing employment flexibility as the most important reason for hiring temporary (or non-regular) workers (Jones and Urasawa 2012).

The proportion of temporary jobs increased substantially in Korea after the financial crisis in 1997 since not only did the government allow firms to use more flexible employment contracts, but also people became desperate for jobs during the severe recession. Holmlund and Storrie (2002) show the incidence of temporary jobs is greatly influenced by macroeconomic conditions and, more importantly, a severe recession can cause a surge of temporary jobs by not only making firms more liable to offer temporary contracts, but also by making workers more willing to accept them.

Another regulation in the bill was to prohibit discrimination against temporary workers who perform tasks similar to permanent workers in the same firm. According to the new regulation, temporary workers – workers on fixed-term contracts, part-time workers, and temporary agency workers – can submit complaints of discriminatory treatment relating to wages and working conditions to the Korean Labor Relations Commission (Grubb et al. 2007). However, only 2,443 cases affecting 5,262 workers were filed between July 2007 and February 2012 (Jones and Urasawa 2013), and hence the number of correction orders by the Korean Labor Relations Commission has been small. Thus, the regulation is considered to have had little effect on the labor market.

There are some exceptions in the new regulation, and the following cases are excluded from the application of the two-year maximum duration for fixed-term employment: (i) firms in the private sector with fewer than five employees, (ii) workers aged 55 or older at the time of signing a fixed-term contract, (iii) Workers who work less than 15 h per week regularly, (iv) workers holding doctoral degrees or other highly technical and professional qualifications, (v) part-time instructors in tertiary education institutions, and (vi) workers subject to other contract duration specified by other laws (Yoo and Kang 2012).

In this study, the termination of employment includes both voluntary and involuntary separations from jobs. There are some reasons why both kinds of separations are included in the sample. First, all separations may result from the interaction between employers and employees, which is the main concern of this study. Second, an interviewee may choose “voluntary separation” as a reason for his/her job termination, even though he or she was dismissed. Third, although the questionnaire, on which our data is based, has a question asking about a specific reason for job separation, the question response rate is only 56.8%.

KLIPS is a longitudinal survey of the labor market/income activities of households and individuals residing in urban areas. Being the first domestic panel survey on labor-related issues, it has served as a valuable data source for microeconomic analysis concerning labor market activities and transitions. This data set is publicly available on the Korea Labor Institute’s website (https://www.kli.re.kr/klips_eng/index.do).

KLIPS classifies salary and wage workers into three groups: 1) Regular worker: workers whose employment contract period is at least one year, or workers who can be kept employed as long as he/she wants if their employment contracts are not pre-specified. 2) Temporary-contract worker: workers whose employment contracts are at least one month and less than one year, or the workers who expect their job to be terminated within a year if the period of their contracts is not specified in advance. 3) Casual worker (or day laborer): workers whose contract period is less than one month, or the workers who are hired and paid on a daily basis.

Another way of describing the changes in analysis time r is a survivor function, which is the probability that there is no termination of employment prior to the analysis time r. The survivor function is simply the reverse cumulative distribution function: S(r) = 1 – F(r) = Prob(R > r). The survivor function can be estimated nonparametrically using Kaplan–Meier’s nonparametric version of the survivor function S(t): \(\widehat{S}\left(r\right)= {\prod }_{j|{r}_{j}\le r}(\frac{{n}_{j}-{f}_{j}}{{n}_{j}})={\prod }_{j|{r}_{j}\le r}(1-\widehat{h}\left({r}_{j}\right))\) where \({n}_{r}\) is the number of jobs at risk at r, and \({f}_{r}\) is the number of jobs terminated at r.

The overall shape of the hazard functions for both the control and treatment groups is consistent with the prediction of Jovanovic’s (1979a) model. He regards the quality of a job match as an “experience good”, which is revealed as firms and workers experience it. The hazard of employment termination is low at the very early stage and then increases as quality is revealed and bad matches are weeded out. However, the hazard declines afterward, since the remaining matches are progressively better. This main prediction from the theoretical model was also confirmed empirically by Farber (1994). Using monthly data, he showed the hazard of a job ending increases to a maximum at 3 months and declines thereafter.

A common method for analyzing duration data is the Cox proportional hazards model. The Cox model is based on the assumption of proportional hazards (PH) across different covariates, which means that the relative hazard remains constant over time with different predictor or covariate levels (Cleves et al. 2008). However, the PH assumption is too strong to apply to our analysis because employment termination hazards vary across the job spells and the policy change may affects disproportionally the termination hazards at each month of tenure. Thus, this study employs probit model that allows us to verify the changes in the termination hazards across the analysis time (r).

In the analysis, the duration of a job (r) is restricted to thirty months because there are just a few observations after thirty months of tenure.

In the presence of worker’s unobservable heterogeneity, the duration dependence in the probability of job separation cannot be estimated consistently without controlling for the heterogeneity. Farber (1994) proposed to use the information on worker’s previous jobs as one way of controlling worker heterogeneity. He showed the frequency of job change prior to the start of the current job has a positive impact on the hazards of job separation. I found a similar result that the hazard is positively related to the number of previous jobs since a worker entered the labor market.

All the coefficients of the previous unemployment rates that I tested show negative signs, and this can be interpreted in terms of workers’ incentives. Higher unemployment rates imply that temporary workers have fewer outside opportunities to find better jobs and, accordingly, higher unemployment increases their interest in remaining in their jobs (Güell and Petrongolo 2007).

Since job characteristics such as firm size and hours of working could change over time in a job, it is not obvious in some jobs whether a worker is excluded from the regulation throughout a work period. To identify the exceptional cases in terms of firm size and working week, I used information on jobs (firm size and hours of working) at the date of the last interview. As for the age of a worker, a worker who was aged 55 or older at the beginning of a job is considered an exceptional case.

A discernible change in the results after excluding exceptional cases is that the coefficient estimates on an interaction term for twenty-seven months of tenure become statistically significant. Since the sign of the estimate is positive, this means jobs in the subsample are more likely to be terminated around twenty-seven months of tenure after the reform. I guess this is because for some converted workers their wages remained still at a low level even after their temporary contracts were converted to permanent ones. Usually, in the Korean labor market, temporary workers suffer from not only low wages but also a lack of job security, and hence they want to get a regular job that is characterized by high wages and better job security. However, after the reform, some firms comply with the new regulation offering a permanent job to a worker on a temporary contract for two years but keeping wages at a low level. Therefore, some converted workers who are not satisfied with their low wages may find other jobs with higher wages, which increases job termination hazards around twenty-seven months of tenure.

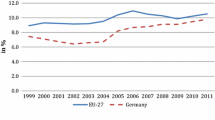

In fact, the Korean labor market had not been severely impacted by the 2008–2009 global recession compared to those of other OECD countries. For example, the unemployment rate for people aged 15–64 in the U.S and the European Union (27 countries) increased by 3.5%p and 2.1%p in 2008 respectively, while the unemployment rate increased by only 0.5%p in Korea.

I use either the pre-reform period (① 2001–2006) or post-reform period (② 2010–2015) in each placebo test in order to exclude the possibility that a false reform could capture the effect of the reform if observations from both pre-reform and post-reform periods are used for the test.

In Korea, working very long hours is widespread. In 2000, almost 40% of Koreans worked 55 or more hours on a regular basis, which was three times more than the OECD average. Long average working hours reflect a combination of long regular working hours and paid/unpaid overtime (Hijzen and Thewissen 2020). Especially, unpaid overtime work had been encouraged for workers implicitly in Korea because employers usually evaluated their employees based on whether they work long hours. The high incidence of long working hours recently has been pointed out as the main source of low productivity performance and the high rate of fatal work injuries in Korea (Park and Park 2019). As a result, the Korean government introduced a major working time reform that lowers the statutory limit on weekly working hours from 68 to 52 during the period 2018–2021.

To identify permanent workers among regular workers, I use a criterion whether a regular worker is provided with social insurance programs from his/her employer in a job as above.

Blundell and Costas Dias (2000) suggest the common trends condition that is crucial for difference-in-differences estimator to be consistent, which means that treatment and control groups respond to macroeconomic shocks in the similar way.

The results are contrary to the main finding of Engellandt and Riphahn (2005). They showed empirically the likelihood of working unpaid overtime is much higher for temporary workers than permanent ones in Switzerland. They argued that temporary workers have more incentive to exert greater effort because temporary contracts function as a screening tool and provide stepping stones into permanent employment in Switzerland. On the other hand, Landers et al. (1996) and Booth et al. (2003) suggested permanent workers have incentives to prove they are hardworking. In Korea, it seems that both higher promotion incentives for permanent workers and limited advancement from temporary to permanent employment result in longer (unpaid) overtime hours and a higher chance of working (unpaid) overtime for permanent workers.

The conditional average marginal effect (AME) is computed by averaging conditional marginal effect (ME) for each observation i over all sample values. For example, the conditional AME of temporary-contract (Temp) is computed as follows: \(AME\left(Temp|After=0, Post\ \mathrm{job}=0\right)=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}{ME}_{i}\left(Temp\right|After=0, Post\ \mathrm{job}=0)\) where \({ME}_{i}\left(\bullet \right)= \widehat{P}({y}_{i}=1 | Temp=1, After=0, \mathrm{Post}\ \mathrm{job}=0, {\boldsymbol{ }{\varvec{X}}}_{{\varvec{i}}};\boldsymbol{ }\widehat{{\varvec{\beta}}},\boldsymbol{ }\widehat{{\varvec{\pi}}})- \widehat{P}({y}_{i}=1 | Temp=0, After=0, Post\ job=0, {\boldsymbol{ }{\varvec{X}}}_{{\varvec{i}}};\boldsymbol{ }\widehat{{\varvec{\beta}}},\boldsymbol{ }\widehat{{\varvec{\pi}}})\). Similarly, the conditional AME of After and Post-job stand for \(AME\left(After|Temp=0, Post\ \mathrm{job}=0\right)=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}{ME}_{i}\left(After\right|Temp=0, Post\ \mathrm{job}=0)\) and \(AME\left(Post\ \mathrm{job}|Temp=0, After=1\right)=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}{ME}_{i}\left(Post\ \mathrm{job}\right|\mathrm{Temp}=0, After=1)\) respectively.

References

Amuedo-Dorantes C (2000) Work transitions into and out of involuntary temporary employment in a segmented market: evidence from Spain. ILR Rev 53(2):309–325

Amuedo-Dorantes C (2001) From “temp-to-perm” Promoting permanent employment in Spain. Int J Manpow 22(7):625–647

Alba-Ramirez A (1998) How temporary is temporary employment in Spain? J Lab Res 19(4):695–710

Bentolila S, Dolado JJ (1994) Labour flexibility and wages: lessons from Spain. Econ Policy 9(18):53–99

Blanchard O, Landier A (2002) The perverse effects of partial labour market reform: fixed-term contracts in France. Econ J 112(480):F214–F244

Blundell R, Costa Dias M (2000) Evaluation methods for non-experimental data. Fisc Stud 21(4):427–468

Boockmann B, Hagen T (2008) Fixed-term contracts as sorting mechanisms: Evidence from job durations in West Germany. Labour Econ 15(5):984–1005

Booth AL, Francesconi M, Frank J (2002) Temporary jobs: stepping stones or dead ends? Econ J 112(480):F189–F213

Booth AL, Francesconi M, Frank J (2003) A sticky floors model of promotion, pay, and gender. Eur Econ Rev 47(2):295–322

Cleves M, Gould W, Gould WW, Gutierrez R, Marchenko Y (2008) An introduction to survival analysis using Stata. Stata Press, College Station, TX

D’Addio AC, Rosholm M (2005) Exits from temporary jobs in Europe: A competing risks analysis. Labour Econ 12(4):449–468

Engellandt A, Riphahn RT (2005) Temporary contracts and employee effort. Labour Econ 12(3):281–299

Farber HS (1994) The analysis of interfirm worker mobility. J Law Econ 12(4):554–593

Grubb D, Lee JK, Tergeist P (2007) Addressing labour market duality in Korea. OECD Social Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 61. http://www.oecd.org/korea/39451179.pdf

Güell M, Petrongolo B (2007) How binding are legal limits? Transitions from temporary to permanent work in Spain. Labour Econ 14(2):153–183

Hijzen A, Thewissen S (2020) The 2018–2021 working time reform in Korea: A preliminary assessment, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 248, OECD Publishing, Paris

Holmlund B, Storrie D (2002) Temporary work in turbulent times: the Swedish experience. Econ J 112(480):F245–F269

Jones RS, Urasawa S (2012) Promoting social cohesion in Korea. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 963, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k97gkdfjqf3-en

Jones RS, Urasawa S (2013) Labour market policies to promote growth and social cohesion in Korea. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1068, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k43nxrmq8xx-en

Jones RS, Urasawa S (2014) Reducing income inequality and poverty and promoting social mobility in Korea. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1153, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jz0wh6l5p7l-en

Jovanovic B (1979a) Job matching and the theory of turnover. J Polit Econ 87(5, Part 1):972–990

Jovanovic B (1979b) Firm-specific capital and turnover. J Polit Econ 87(6):1246–1260

Kahn LM (2007) The impact of employment protection mandates on demographic temporary employment patterns: International microeconomic evidence. Econ J 117(521):F333–F356

Kahn LM (2012) Labor market policy: A comparative view on the costs and benefits of labor market flexibility. J Policy Anal Manage 31(1):94–110

Kang BG, Yun MS (2008) Changes in Korean wage inequality, 1980–2005, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 3780. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn. https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-20081126399

Landers RM, Rebitzer JB, Taylor LJ (1996) Rat race redux: Adverse selection in the determination of work hours in law firms. Am Econ Rev 86(3):329–348

Lazear EP (1990) Job security provisions and employment. Q J Econ 105(3):699–726

Lee DR (1996) Why is flexible employment increasing? J Lab Res 17(4):543–553

Marinescu I (2009) Job security legislation and job duration: Evidence from the United Kingdom. J Law Econ 27(3):465–486

OECD (2004) OECD Employment Outlook 2004. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2004-en

OECD (2013) Strengthening social cohesion in Korea. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264188945-en

OECD (2016) OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2016. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-kor-2016-en

Park W, Park Y (2019) When Less is More: The Impact of the Regulation on Standard Workweek on Labor Productivity in South Korea. J Policy Anal Manage 38(3):681–705

SaKong I (1993) Korea in the World Economy. Institution for International Economics, Washington, DC

Yoo G, Kang C (2012) The effect of protection of temporary workers on employment levels: evidence from the 2007 reform of South Korea. Ind Labor Relat Rev 65(3):578–606

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Tables 6,

7 ,

8,

9,

10,

11,

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, T. The Impact of Employment Protection on the Probability of Job Separation: Evidence from Job Duration Data in South Korea. J Labor Res 43, 369–414 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-022-09336-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-022-09336-z