Abstract

Despite having essential health needs regarding sexual and reproductive health services (SRHS), young people (e.g., adolescents) in many countries show low use of such services. The World Health Organization advocates fostering young people’s autonomy to access health services to address this global health problem. However, there are gaps in the literature to understand how young people’s autonomy can be fostered to access SRHS. In 2019–2020, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 45 young people aged 14–23 years old in Colombia to explore how they might wish to have their autonomy fostered in accessing SRHS. Research in different cultural contexts has shown that young people generally do not wish to discuss sex with their parents. By contrast, most of our participants expressed a strong wish for the ability to talk openly with their parents about their sexual and reproductive health. One of the main complaints of these young people was that their parents lacked the necessary knowledge to help them make informed decisions related to their sexual and reproductive health (e.g., choosing a contraceptive option). As a potential solution, participants were enthusiastic about initiatives that could provide parents with comprehensive sex education to assist young people in making informed choices for their sexual and reproductive health, including how to access SRHS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2015, the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (Every Woman Every Child, 2015) was introduced to help achieve part of the United Nation’s (UN) Sustainable Development Goals related to health (UN, 2015). The Global Strategy notably includes ensuring universal access to sexual and reproductive health services (SRHS), and was the first time that a global health initiative of this magnitude recognized adolescents as a distinct group – different from children and adults – with unique health needs and challenges that must be addressed. To help reach the goals of the Global Strategy related to adolescents (i.e., young people), in 2017 the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents: guidance to support country implementation (AA-HA!) (WHO, 2017).

One of the leading global health challenges emerging from the literature on young people’s health is that they have many unmet healthcare needs, such as those related to sexual and reproductive health (Mazur et al., 2018; Nature, 2018; Patton et al., 2016). This situation results from many factors, including young people’s inexperience and lack of knowledge about how to access and use healthcare services in their communities (Patton et al., 2012). As a solution, AA-HA! suggests fostering young people’s autonomy to access health services, including SRHS, in specific cultural contexts. However, there are gaps in the literature regarding what fostering young people’s autonomy to access SRHS would entail in different countries (Brisson et al., 2021b). Thus, raising important questions for researchers and policy makers: Should fostering autonomy be done through public health promotion campaigns targeted specifically to young people? Should it be part of sex education in schools? Do young people wish to have their autonomy fostered to access SRHS, and if so, how? The answers to these questions will most likely vary across countries and cultural communities.

From a justice perspective, and as advocated in AA-HA!, young people should be meaningfully involved in initiatives that directly affect them (Mabaso et al. 2016). Just as importantly, for group-specific health initiatives to be efficient and effective (i.e., pertinent and adapted to the needs of the group), and to maximize the chance of the intervention’s success, members of the target group should be consulted (Israel et al., 2010; Kon, 2009; Minkler et al., 2003). With these considerations in mind, our study consulted young Colombian people to ask whether they would want their autonomy fostered to access SRHS (as suggested by the WHO), and if so, how they would want their autonomy fostered.

There were different reasons for choosing Colombia as the focus of our research. One important reason is that most research done with young people is conducted in high-income countries (HIC), yet most young people live in low and middle-income countries (LMIC), like Colombia (Blum & Boyden, 2018; Vandermorris and Zulfiqar 2017). Given the evident cultural, socio-political, socio-economic differences between HIC and LMIC, including different healthcare delivery environments, one cannot expect research in the former to necessarily represent the reality of people in the latter.

Adolescence is socially and culturally defined, and cultural markers will often define an adolescent’s entry into adulthood (Ledford, 2018; Sawyer et al., 2018); simultaneously, there are no objective (e.g., biological) markers to define the end of adolescence and the start of adulthood (Bédin, 2009; Sawyer & Patton, 2018). In parallel, human sexuality is also culturally shaped (Parker, 2009), which also influences questions of autonomy to access and use SRHS. Hence, it is crucial to conduct research with young people in different cultural contexts in order to understand their diverse experiences worldwide.

In terms of young people’s autonomy to access SRHS, Colombia is unique since there are no laws preventing adolescents from accessing some health services without parental consent or accompaniment. For example, a 13-year-old girl in Colombia may independently access contraceptives or have an abortion in a clinic without parental involvement, although this may not be widely known by young people (Brack et al., 2017; Brisson et al., 2021a; Prada et al., 2011).

Furthermore, compared to neighboring countries, the Colombian government has taken a more sex-positive approach to young people’s sexuality, notably by investing in initiatives to promote young people’s sexual and reproductive health. According to the Colombian Health Ministry website (2021) “it is time that adolescents and young people experience their rights from a positive perspective: the right to enjoy sexuality and self-determine their reproduction” (first author’s translation). This view differs substantially from fear-based approaches to young people’s sexuality that are still common in many other LMIC, including in Latin America (Schalet, 2004). However, while some governmental initiatives have sex-positive perspectives, this view is not necessarily shared by the majority of the Colombian population, and high-profile conservative religious groups still actively fighting against LGBT + rights (Corrales & Sagarzazu, 2019), for example.

Previous research on the topic of young people’s sexuality, in general, has shown that they tend not to want to discuss sex with their parents – particularly concerning their access to SRHS. This is the case in different countries, such as in the United States (Lehrer et al., 2007), Ethiopia (Muntean et al., 2015), South Africa (Vujovic et al., 2014), and the United Kingdom (Garside et al., 2002). Data show that confidentiality and privacy are central for young people regarding accessing SRHS; for example, young people generally do not want their parents to know that they want to use contraceptives or get tested for a sexually transmitted infection (STI) (Fuentes et al., 2018; Lawrence et al., 2011; Pampati et al., 2019). Hence, we initially assumed at the outset of our research that young Colombian people would want to have their autonomy fostered to access SRHS without parental involvement, but interestingly, this proved not to be the case, and for multiple reasons.

Objectives

The study’s first objective was to learn whether young people would want to have their autonomy fostered to access SRHS. In the event that that some adolescent participants wished to have their autonomy fostered, the second objective was to understand how this should occur. The third objective was to understand why young people would want their autonomy fostered in a particular way and then explore how this could be implemented.

Methodology

Design

Between August 2019 and February 2020, the lead author conducted semi-structured audio-recorded interviews, in Spanish, with 45 young Colombian participants; the interviews were then transcribed and translated from Spanish to English. The methodological approach of semi-structured interviews enabled a detailed exploration, with participants, of their views on the topic (Adams, 2015; Pope et al., 2002; Sankar & Jones, 2007), specifically if and how they would want their autonomy fostered to access SRHS. Participants were also given the opportunity to share past experiences and to provide meaning to their answers (e.g., elements they might have enjoyed that fostered their autonomy to access SRHS).

Before the interviews, participants were asked demographic questions, such as how they identified their gender and whether they were currently enrolled in school. All participants were asked the same core questions from the interview guide, e.g., how they interpreted the WHO concept of “fostering autonomy” for adolescents to access SRHS. However, during the interviews, participants were asked different questions depending on their answers. For example, a participant who would never have accessed SRHS because their parents forbid them did not have the same follow-up questions as participants who shared having already accessed SHRS with a parent.

As mentioned above, previous data on the topic in different cultural contexts have shown that young people generally do not want to discuss sexual and reproductive health with their parents. Hence, in this research project, the guide for the interview questions were not initially developed with the view that participants would attribute an important role to parents regarding their autonomy to access SRHS. Originally, there were no specific questions about parents to be asked during the interviews (the interview guide was not pretested). However, the methodological approach incorporated flexibility in adjusting questions as needed (Galletta, 2013). After the first five interviews, it became evident that participants wanted to talk about their parents’ involvement in fostering autonomy. As such, a new section was added to the interview guide: the remaining forty participants were asked if they would want their parents to receive sex education and were then invited to expand upon their answers, particularly as these related to the question of their autonomy.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were between the ages 14 and 23 years, consonant with our main inclusion criterion of participants to be aged between 10 and 24 years, corresponding to the new definition of adolescence increasingly used in global health research and policymaking (Sawyer et al., 2018), and which also corresponds to the WHO’s definition of young people (WHO, 2014). As previously mentioned, the period of adolescence and the transition into adulthood is culturally defined. As such, there is a critical methodological reason for extending the age range for studies with young people: it allows to understand the similarities and differences between younger and older adolescents and young adults.

The initial targeted minimum sample size was twenty participants, and the cut-off point was sixty participants, in order to maximise the diversity of young people’s opinions, realities, and experiences (e.g., compare answers between older and younger participants). In line with the research objective, the recruitment goal was to have at least two main categories of participants – those who had and had not previously accessed SRHS – in order to hear young people’s voices regarding their experiences with autonomous access to SRHS.

Interviews were conducted between August 2019 and February 2020 in the two Colombian departments, Antioquia and Valle del Cauca, in both rural and urban contexts. In Antioquia, participants were recruited in the cities of Medellin (large city), Rionegro (small city), and Santa Fe de Antioquia (rural area), while in Valle del Cauca participants were from Cali (large city) and Palmira (small city). It was left at the discretion of the participants to choose where they wished to do the interview, e.g., in private room in a clinic, at a library, on parc bench.

Different approaches were used to recruit participants. One approach was through the help of Profamilia, a network of non-profit health clinics across Colombia that offer accessible SRHS to the population and which is a strong advocate of sexual and reproductive health rights (e.g., trans rights, access to abortion, promotion of comprehensive sex education). Profamilia also offers services specialized for young people (e.g., youth psychologists, social workers) and frequently organizes events for young people, in and outside their clinics. Recruitment posters for the study were posted in two Profamilia clinics (Medellin and Cali), and health professionals who saw young patients shared information about the research project.

In addition, study information was shared at social events involving Profamilia employees outside the clinics in community events (e.g., educative initiatives with schools, community organizations and promotion events) where young people were present (not as patients). The employees would present the research project while the researcher (first author) was there (e.g., community centers), and the employees would invite young people to approach the researcher or take an information sheet about the research project. Snowball sampling was the most effective means of recruitment, with participants and other young people sharing information about the research with their friends and peers. Further, a nurse presented the research project to students in a high school (in Santa Fe de Antioquia). These various recruitment strategies ensured diversity in young people’s experiences with access to SRHS (e.g., with Profamilia or other clinics) and some participants that had never used SRHS.

At the beginning of the study, some young people asked if they would have to talk about their sexual practices to participate in the interview and hinted that they would feel uncomfortable discussing this subject. The researcher clarified that no specific questions would be asked about the participants’ sexual practices, and that the focus of the interview was on young people’s autonomy and access to SRHS. From then on, this clarification was presented to all potential and actual participants, through the consent form and information sheet (which stated that participants did not have to answer any questions that made them uncomfortable, nor would they be required to give any justification), and prior to each interview. These written and verbal confirmations appeared to help participants feel more at ease with participating in the interview.

Data Analysis

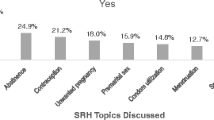

The interviews were first transcribed in their original language (Spanish), and transcripts initially analyzed in Spanish to preserve the cultural meanings of participants’ answers. Each transcript was read at least twice to generate a preliminary sense of the themes and participants’ opinions. The first step of data analysis consisted of classification (Gaudet & Robert, 2018). The core interview questions were separated into sections (e.g., “Would you want your parents to receive sex education?” “What kind of topics would you want to be part of the sex education for your parents?”). The interview excerpts answering the particular question were then documented under each section for thematic analysis (Braun and Clark 2006) (Fig. 1).

The interview excerpts were analyzed by highlighting and coding the similarities and differences of responses while simultaneously paying attention to participants’ demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age) (Maher et al., 2018). This coding approach allowed for the identification of specific trends and variations between answers and experiences based upon participants’ various contexts (Coenen-Huther, 2006).

The analysis of Part A involved getting a general sense of the participants’ position regarding the WHO concept and call to “foster autonomy” for young people to access SRHS and to better understand the reasons behind the participant’s stance (e.g., why the participant accepted or rejected the WHO initiative). For Part B, the goal was to analyze the place or role that participants attributed to their parents on the question of supporting their autonomy to access SRHS (e.g., if the participant discussed the topic with their parents). Part C entailed documenting participants’ willingness for their parents to receive comprehensive sex education, in order to then be able to understand the reasons behind participants’ answers. Finally, Part D consisted of an analysis by themes (Paillé and Mucchielli 2012), i.e., the topics that participants would want to be part of their parents’ sex education were classified into main categories.

After the mapping and analysis of the data, we conducted an ethical analysis as an analytic frame for a rich conception of autonomy and its application to the WHO notion of fostering young people’s autonomy to access SRHS. The purpose was to identify the ethical questions arising from participants’ answers and determine the potential implications for health policy, and then to develop possible practical recommendations.

Ethical considerations

The University of Montreal’s Research Ethics Committee first evaluated and approved the research project (CERSES- 19-049-P), which was then evaluated and approved by the Profamilia’s research ethics committee (which included a lawyer). Before participating in the interview, participants were asked to read an information sheet about the project and sign a consent form. Participants were provided all the necessary information to make an informed decision about whether they wished to participate in the interview. Participants were also given a list of free local resources in the event that they were in need of support following the interview (e.g., social workers). Pseudonyms were given to every participant to protect their anonymity.

Parental consent was not asked nor required (as approved by the research ethics committees), based on the grounds that asking for parental consent could be a potential barrier to free and informed participation in the study. The decision to not ask for parental consent was supported by national and international research ethics guidelines, including the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences 2017). Under certain conditions and with justification (and approval by a research ethics committee), it is possible to waive parental consent for research with minors, notable when it is not possible or desirable, and the research involves low risk for participants.

Results

The first part of the results section presents the participant profiles and is followed by participants’ responses regarding whether they wanted their autonomy fostered to access SRHS and the reasons supporting this view. Subsequently, participants’ responses will be presented on why they would want comprehensive sex education to be provided to their parents to help foster autonomy to access SRHS. Finally, we present the topics that participants would like to be part of the sex education for their parents.

Participant Profiles

A total of 45 young Colombian people were interviewed; before recording the interviews, participants were asked demographic questions (see Table 1). Five participants were recruited in a school through the help of a nurse, 29 participated via snowball sampling and participation at social events (e.g., presentation of the research in a community center), and the other 11 participants were recruited from visiting Profamilia clinics (e.g., poster). Participants were free to define their gender. There was a close equal representation of male and females, with one non-binary participant. The age distribution for participants was from 14 to 23 years old (the inclusion criteria was 10–24 years old), with 19 years old being the average. Participants were invited to share their estrato; Colombian socio-economic classes assigned by the government regarding one’s area of residency. In Colombia, there are six officials estratos: 1 is the lowest and 6 the highest. Most of the Colombian population is in the lower three estratos, with a minority in the upper three estratos. More than three-quarters of participants were from the estratos two and three, and none from the upper two estratos (five and six).

The Pertinence of Fostering Autonomy to Access SRHS

The study did not take for granted that participants would necessarily want their autonomy fostered to access SRHS; they might have rejected the AA-HA! initiative, for example, seeing it as paternalistic or believing that they already possessed the necessary knowledge and skills to exercise their autonomy to access SRHS. However, this was not the case. Participants were unanimous regarding the pertinence of initiatives to foster their autonomy to access SRHS. They understood the idea of “fostering autonomy” as an opportunity to gain more knowledge that could be useful for them, and many noted that they lacked some understandings of topics related to sexual and reproductive health. This perceived lack of knowledge around accessing SRHS was more pronounced for some participants than others (e.g., those that did not receive comprehensive sex education in school).

Participants were asked if they had received sex education in school. While many participants had received sex education in school (42%), the remaining participants (58%) stated either having received no sex education or had received “very bad” sex education. Some participants received abstinence-only education, which does not qualify as comprehensive sex education according to international guidelines, e.g., UNESCO’s International technical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach (2018). Regardless of whether participants had received sex education in school, there was an overwhelming perception that their sex education was lacking in many aspects, including teaching about how to access SRHS. The following interview excerpt exemplifies participants’ experience with sex education in school:

Andres (male, 23 years old).

-

Interviewer: You told me earlier that you received sex education in school, would it have been something you would have liked to be part of your sex education? (teaching how to access SRHS)

-

Andres: That is something I would have liked very much, that they amplify it a lot more. Because when I received sex education in school, the teachers presented it in a very silly way, like very childish. To teach properly in great depth – to teach truthfully what needs to be taught – it has to be realistic with a kid.

-

I: Can you elaborate a bit more?

-

A: Alright, look, let’s say I am a 14-year-old kid… I’ll tell you my own experience when I received sex education in school. I was sitting in the classroom and saw the teacher saying “these are the parts of the body, these are the genital parts, and the genital parts are the penis and testicles.” So, it was super basic. You want them to teach you about real stuff. I was thinking like “what am I seeing here?” I saw this as unimportant material. I knew that in the future I would want to have sexual relations, so that material was not useful for me. So yeah, I had “sex education” but I never had a class that went in depth to explain what really happens between a man and a woman, never.

-

I: So as a young person you wanted your sex education to go beyond the basic biology and talk about relationships?

-

A: Exactly! All of it!

-

I: What about teaching how to access sexual health services?

-

A: Yes, I would have wanted that they give information on where I can go ask questions, where I can get condoms, and so on. So, it wasn’t really sex education, it was super basic, it was biology stuff and that’s it.

As evident from this interview excerpt, Andres recognized the shortcomings of the sex education he received in school and he could confirm the topics he would have liked to be discussed, such as how to access SRHS and where to obtain more information related to sexual and reproductive health. Andres’ opinion echoed most of the other participants’ perceived gaps in their knowledge related to sexual and reproductive health, which led participants to endorse AA-HA!’s concept of developing ways to foster young people’s autonomy to access health services, and SRHS in this case.

The Place of Parents Regarding their Children’s Autonomy to Access SRHS

The question of fostering autonomy to access SRHS was initially framed in the interviews in relation to sex education in school. However, many participants would bring the discussion back to their parents. As previously mentioned, and in keeping with previous research on the topic, the study was not originally conceived with the view that participants would attribute much importance to the role or place of their parents in supporting autonomy to access SRHS. Mariana was one of those first interviewed who led to the introduction of a new section in the interview guide about parents and their relation to the question of young people’s autonomy:

Mariana (female, 19 years old).

-

Interviewer: Do you think we should do the promotion of adolescents’ autonomy in healthcare as part of sex education?

-

Mariana: Yes, but I think it should be the responsibility of parents.

-

I: More than sex education in school?

-

M: Equally.

-

I: And why with parents?

-

M: Because young people should always talk first with their parents about sex.

Mariana explained during her interview that it was important for her to have her mother involved in helping her choose a contraceptive option, as opposed to making the decision by herself. As will be developed in the next sections, like many of the other participants, Mariana’s mother did not have more knowledge than her daughter about contraceptives. Nonetheless, Mariana accorded great importance to her mother being involved in discussions around her contraceptive choice.

Analysis of the interviews found an almost unanimous belief among participants that their parents lacked general knowledge about sexual and reproductive health, which reflects participants’ own sense of missing sufficient or complete knowledge related to their sexual and reproductive health. Two main points emerged regarding the information that participants believed their parents were missing: (1) a lack of parental understanding of the reality of young people’s experiences concerning sexual and reproductive health, and (2) a general lack of parental knowledge about accurate sexual and reproductive health information. The following interview excerpt helps highlight these two points:

Sebastian (male, 21 years old).

-

Interviewer: How do you think we could promote the autonomy of adolescents to access sexual and reproductive health services?

-

S: In school and with parents.

-

I: Both?

-

S: Well, I think more with parents.

-

I: Why is that?

-

S: Who is gonna know you more than your own parents? With who are you gonna have more trust than in your parents? So, I think parents should be the first people we talk with when we start being sexually active.

(…)

-

I: Do you think it would be a good idea to start giving sex education classes to the parents of adolescents?

-

S: Yes. Yes, I think it would be good, as much for adolescents as for parents. Because like I was telling you, this is something we should start to implement in the 21st century. We already know or we should start to be aware that parents are from an older era and had completely different education. Maybe they’ve had sex education or maybe they didn’t get any, but I think you’re never too old to learn. Because as much for us young people as for parents, we can all learn something.

When asked why participants attributed such importance to discussions with their parents about sexual and reproductive health, a significant number were unable to give a concrete response. Nonetheless, for those who were able to develop an answer, the question of trust was a central element, notably as observed in the previous interview excerpt.

Discussing Sexual and Reproductive Health with Parents

The previous interview excerpts helped provide a foundation for grouping the opinions of participants on the topic. When analyzing the interviews more thoroughly, it is possible to recognize different experiences for participants in discussing sexual and reproductive health with their parents. The following sections presents those different realities by types of experiences and participant preferences.

Wanting to Talk but Being Unable To

Some participants expressed wanting to talk about sexual and reproductive health with their parents but being unable to, either because they did not feel comfortable initiating the conversation with their parents, or because parents refused to discuss the topic when it was brought up by the young person. This latter situation was the case for Isabella. During her interview, she explained that she had wanted to start using a birth control implant because she wanted to begin having sexual relations with her boyfriend:

Isabella (female, 14 years old).

-

Interviewer: What would have you liked to be your mother’s reaction? (when asked to start using contraceptives)

-

Isabella: Well, from my mom, I was expecting this reaction because she’s very closed-minded around the topic of sexuality. I always want to talk to her about the topic, but she always asks me to change the topic.

Wanting to Talk and Being Able to

While some parents, like Isabella’s mother, avoided the topic, other participants explained that their parents were more engaged with or open to discussing sexual and reproductive health.

Sebastian (male, 21 years old).

-

Interviewer: You’re telling me you’ve spoken to your parents about your experiences?

-

S: Yes. I’ve spoken to my parents about it. Now it is not a mystery. I’m gonna tell them that I’m gonna go out with a (girl) friend and it is not a mystery.

-

I: At what age was the first time you had that talk?

-

S: At like 16 or 17.

-

I: And your parents were not uncomfortable that you wanted to talk to them about that topic?

-

S: No. They’ve always supported me with this topic. When I would return from school and tell them I’ve had classes on sex education and learned how to use condoms and prevent diseases and all of that, I shared that with my parents, and they supported me. They said “learn and pay a lot of attention, it’s going to be useful for you one day.” The recommendations I’ve always received from my parents was “take care of yourself, take care of yourself, take care of yourself, put the condom on.”

Not Wanting to Talk

While many participants recounted the important place for them of discussions with their parents about sex, this was not the case for a minority of participants who expressly did not to want to discuss the subject with their parents.

Santiago (male, 15 years old).

-

Interviewer: Other participants during their interviews said that they would like to be able to talk more about sex with their parents, it doesn’t sound like that is your case.

-

Santiago: No, not for me.

-

I: Some participants expressed that they would like for their parents to receive sex education to afterward be able to talk more openly with their adolescents on the topic.

-

S: No, no. That’s not the case for me.

-

I: You prefer receiving sex education on the Internet and in school?

-

S: I say that maybe for some young people it could be the case for them, but it is not my case for me, I don’t wanna talk about sex with my parents.

Young people have distinct preferences regarding discussing sex, as do parents (Blakey & Frankland, 1996; Walker, 2001). While some might enthusiastically welcome initiatives promoting comprehensive sex education for parents so that they may better discuss the topic with their children, this enthusiasm might not be collectively or universally shared, something that must then be taken into consideration for any health promotion or policy initiatives.

Topics to Teach Parents

As previously mentioned, most participants supported the idea of initiatives to provide comprehensive sex education to their parents. As follow-up questions, participants were asked what themes or topics they would want their parents to learn about as part of their sex education. Many participants were unable to identify specific topics, but the following sections are some of the main topics suggested by the participants who could answer the question.

Gender Relations and Sexual Identities

A few women participants expressed that in Colombia, the question of sexual and reproductive health (locally referred to as “family planning”) was framed as a responsibility of women. These participants critiqued this view, arguing that family planning should also be something involving men, and that men (e.g., their partners) should have better understandings of reproductive health (e.g., understand how contraceptives work). In echo to this point, there was also criticism about an unequal gendered conception of young people’s sexuality, e.g., some women participants stated that parents were more lenient towards men being more sexually active, whereas women did not experience the same permissive attitude. Participants felt that sex education for parents should involve discussions to challenge these problematic gendered representations.

Elena (female, 22 years old).

-

Interviewer: You think there is a difference between men and women? (regarding perceptions about young people having sexual relations)

-

E: Yes.

-

I: Like?

-

E: I say that men have a lot more liberty. And for women… For women, it’s seen as bad according to some people.

-

I: Do you believe that it is a problem?

-

E: Yes, I believe it should be equal between both.

-

I: Do you think this topic should be part of sex education for parents?

-

E: Yes! Obviously! It would be a good thing to change that way of thinking.

In the same vein of wanting to challenge problematic gender ideologies amongst parents, some participants expressed wanting to challenge parents’ homophobic beliefs through sex education. This was notably the case with Jaime (male, 22 years old):

-

Interviewer: Are there specific themes that you would like them (psychologists teaching sex education) to be specialized in?

-

J: More than anything else, sexual orientation. It is because there are many taboos in relations to that theme. And that taboo affects a lot the liberty of expression. And what I would like from those psychologists is to not only help young people but also their parents. It is because in a lot of homes there is a lot of homophobia. For example, if the son says to his dad that he is a homosexual, his dad is going to reject him.

-

I: So, you would like for the psychologist to talk with the child and their parents together?

-

J: No, better separated. First with the parents to educate them.

Healthy Relationships

Most participants associated sex education with the classic biological approach of prevention, e.g., prevention of pregnancy and STIs. Participants were asked if they would appreciate sex education that went beyond questions of human biology and also explored other themes, like how to have healthy relationships between partners (e.g., how to have good communication with a partner or recognize abusive relationship patterns like jealousy). Collectively – except for three men participants who did not see the pertinence – participants expressed a certain enthusiasm for the idea, particularly as it relates to discussing the topic with parents.

Francia (female, 22 years old).

-

Interviewer: In previous studies, young people have criticized sex education focused too much on biology and they would have liked to talk about other themes like….

-

F: Pleasure?

-

I: Yes, also that, but on how to have healthy relationships. Is that something you would have liked to be part of sex education for yourself or your parents?

-

F: Yes, obviously. When I was at a stage of falling in love, with my first boyfriend, it would have been something important, because, for example, with my first boyfriend, it was terrible, very bad. And I tell myself that if I would have had better support… For example, I’ll give you a comparison between me and my best friend. Her parents were always super close with her, and my parents were very distant. So, I was telling myself that she has the foundations on what to do (in her relationships). I didn’t have the foundations to know what to do.

Options and Advice Regarding Accessing SRHS

While some participants could name with ease topics they would like to be part of the sex education provided to their parents, others had more difficulty. Nonetheless, by analyzing what they shared, we observed that participants wanted their parents to possess knowledge on the topic of sexual and reproductive health so that they can give advice and guide their children in making choices related to their sexual and reproductive health.

Juan-Martin (male, 16 years old).

-

Interviewer: Do you think it would be a good idea that we give sex education to the parents of young people?

-

Juan-Martin: It would be cool because you would teach parents and after that the parents can teach to their kids so that they can learn from them.

-

I: So, you would like that?

-

JM: Yes.

-

I: More with your dad or your mom?

-

JM: Both. So that both my parents can give me good advice.

Comprehensive Knowledge of Sexual and Reproductive Health, and the Lived Experiences of Young People

In connection to the previous point, it is important to note that for parents to be able give sound advice and help guide their children to make informed choices, they must possess factual knowledge related to sexual and reproductive health. Some participants felt that their parents had erroneous beliefs regarding some sexual and reproductive health information (e.g., incorrect notion that contraceptives are unsafe and make young people sterile). This misinformation translated into misunderstanding the reality and aspirations of young people as it relates to their sexual and reproductive health. Consequently, participants expressed wanting to challenge those misconceptions through sex education for their parents.

Luz (female, 19 years old).

-

Interviewer: So, you would like that we do that with your mom? (give her comprehensive sex education)

-

Luz: Yeah, that would be cool.

-

I: And what would you like that we teach her?

-

L: I think more than anything else to make her understand that when someone wants to start family planning it is not because they want to sleep with everyone, it is a form of protection.

-

I: So, beyond a question of pure “biology” as to how contraceptives work, to discuss about the life of young people?

-

L: Yes, exactly.

Fostering Autonomy as a Form of Support

As it relates to the question of autonomy (i.e., the ability to make choices), participants made it clear that they wanted to make their own choices regarding their sexual and reproductive health – they wanted their autonomy respected. None of the participants suggested that they would want their parents (or anyone else) to make decisions for them. Yet, most participants gave importance to the role or place of their parents in supporting their autonomy regarding their sexual and reproductive health (e.g., helping to choose a contraceptive option). That said, why would young people want the involvement of someone else (e.g., a parent) if they ultimately wanted to make their own decisions about SRHS? And why would young people want their parents to receive comprehensive sex education to discuss the topic with them if they do not want their parents telling them what to do regarding their sexual and reproductive health? The answer to these two related questions might be that young people want their parents to confirm and agree with the choices they want to make (e.g., to start using contraceptives or get an HIV test at a clinic). And they want to know that their parents have accurate knowledge of sexual and reproductive health, which would then validate the choices they make through their parents’ confirmation and support. The following interview excerpt helps clarify the value participants attributed to having their parents’ support around their autonomy and sexual and reproductive health.

Monica (female, 23 years old).

-

Interviewer: What do you think of the idea that we provide sex education to the parents of young people?

-

Monica: Yes, I would love that so much.

-

I: Why is that?

-

M: Like I was telling you, because oftentimes us young people want to make decisions that do not agree with them (parents). Obviously, we have to understand that they are the parents and they worry about you and they are responsible of their kids until a certain age. But there is so much stigma and myths and they reproduce it with you without knowing why. They never ask themselves “why am I thinking this way?” So, they simply tell you things like “no, a woman cannot be a single mother,” like those types of things. They simply tell you things like that without actually knowing why they tell it to you. I say that those things are prejudices and that it is very important to eliminate them. It is a very difficult task, but I think that gradually it could happen. But yeah, it is very much needed.

This interpretation of the phenomenon is a hypothesis. Future research is needed to empirically examine whether young Colombian people want their parents to receive comprehensive sex education so that their parents will support and agree with the choices the young people want to make regarding their sexual and reproductive health.

Discussion

In general, and in many countries, the traditional format for teaching sex education to young people has been through content in the school curriculum (Moran 2002; Pilcher 2004). Usually, sex education in schools does not involve parents but is done by employees – e.g., teachers, nurses, sexologists, psychologists, or nuns in some cases in Colombia (as was the situation for some of the participants). Many debates have taken place around sex education for young people, one of the dominant being between “abstinence-only” with “comprehensive sex education” approaches (Beh, 2006; Irvine, 2002). Part of that debate is about determining the level of information about sex and sexuality to be shared with young people, ranging from none to sometimes erroneous information, or either complete, comprehensive, and scientifically based information (e.g., teaching young people their healthcare rights and how to access local SRHS).

Ethically speaking, one major point of tension is determining what is best for adolescents, considering that they are not yet adults but have emerging autonomy that evolves over several years. Often, arguments to limit adolescents’ autonomy and grant parents a greater authority depend on views about when adolescents become “sufficiently” competent and autonomous to learn about and make informed decisions about their sexual and reproductive health.

Parental consent laws differ between countries, but in general have to do with circumstances where parents are allowed to decide whether they permit their adolescents to receive sex education in school or to access SRHS (e.g., STI testing). The ethical reasoning behind parental consent laws is that parents are, de facto, responsible for and often best able to determine what is in the best interests (e.g., health and well-being) of their adolescent children. Our findings can contribute to this debate by looking at the issue from a different angle. If one accepts as a starting point the WHO’s AA-HA! initiative recommendations that adolescent autonomy can and should be fostered, including regarding SRHS access, then we should understand in a nuanced way the place given to parental responsibility and involvement in their adolescent’s autonomy.

First, adolescents’ autonomy is emergent, growing and changing over time (Boykin McElhaney & Allen, 2012); second, adolescence is a concept that is socially and culturally constructed, and that is experienced differently depending on the adolescents and on their parents (Ledford, 2018; Sawyer et al., 2018). Because adolescent autonomy is multifaceted and variable across cultures, countries, and socio-economic groups, fostering autonomy necessarily involves multiple stakeholders: not just adolescents, but also their parents, educators, and health professionals, amongst others.

Participants in our study felt that their parents lacked the necessary knowledge to help them foster their autonomy to make choices related to their sexual and reproductive health. While we did not investigate the level of knowledge parents had about sexual and reproductive health, it is very likely that participants had an accurate view of the situation. Despite these perceived shortcomings on the part of parents, most participants still wanted their parents involved (in different ways) in their sexual and reproductive health choices.

Furthermore, most of the participants trusted their parents regarding their sexual and reproductive health, regardless of whether parents had (or were perceived to have) accurate and in-depth knowledge on the topic. From a social policy perspective, this nuance is important and merits further research to explore the implications for related policies and initiatives (e.g., educative projects with parents) that could lead to beneficial effects for young people’s health and well-being. In terms of fostering young people’s autonomy, providing comprehensive sex education to parents would likely ameliorate respect for young people’s choices and increase young people’s use of SRHS, because both young people and their parents would be more knowledgeable on the topic and so be better equipped to make or support more informed decisions.

Previous studies have explored the topic of parents discussing sex education with their adolescents (Mullis et al. 2021; Walker 2001), for example, documenting the perspectives and attitudes of parents in Nigeria (Orji & Esimai, 2003), Greece (Kakavoulis, 2001), the UK (Walker 2004), Mexico (Atienzo et al., 2009), and Australia (Robinson et al., 2017). However, the focus of those studies was mainly on sex education with the objective of educating young people on sexual health from a classic perspective, such as preventing STIs (e.g., Ashcraft & Murray 2017; Shtarkshall et al., 2007; Walker, 2001). Other studies have explored adolescents’ general interest in discussing sex education with their parents – e.g., in Canada (Byers et al., 2003). Some studies have investigated the factors that can help parents discuss sex education with their adolescents, such as communication skills (Baldwin & Baranoski, 1990; Jerman & Constantine, 2010; Malacane et al. 2016), and studies have explored gender differences in communication patterns between parents and their adolescents (Evans et al., 2020). In parallel to our research’s findings that demonstrate that Colombian adolescent participants wanted to discuss sex with their parents, studies in different cultural contexts shows that adolescents can be unsure about wanting to talk about sex with their parents, notably, because of shyness and embarrassment (Diiorio et al., 2003). This is the case, for example, in Kenya (Crichton et al., 2012), Nambia (Nambambi & Mufune, 2011), Scotland (Ogle et al., 2008), the US (Afifi et al. 2008), and Vietnam (Trinh et al., 2009). However, to our knowledge, studies have not yet explored extensively the question of choice and autonomy of young people to access SRHS, as in the present research. As previously mentioned, research in different cultural contexts has shown that adolescents prefer privacy and confidentiality when SRHS are concerned (e.g., Lehrer et al., 2007). It would be pertinent for research to explore the relationship between parents’ discussions about sex education and adolescents’ access to SRHS.

Our study demonstrates that one possible way to foster the autonomy of Colombian youth to access health services, and specifically SRHS, would be through providing comprehensive sex education to their parents. Comprehensive sex education to parents should thus be seen as a complementary measure to the sex education provided to young people in school. While not investigated in the context of this research, it may be the case that discussing the question of autonomy (i.e., making choices) and access to SRHS may be less suitable in a classroom context, in some countries or cultures, and so be more appropriately addressed through discussions between parents and their children.

Recommendations

The study findings enable us to propose two major recommendations.

The need for further research on parental views of young people’s autonomy

Research should be conducted with Colombian parents to determine whether (1) they would want to receive comprehensive sex education, and (2) they would want to talk about sexual and reproductive health with their children. While Colombian youth might want to discuss sex with their parents, it is possible that their parents are either not interested or uncomfortable discussing this topic, and so might (or might not) prefer teachers, health professionals, or other educators to be responsible for providing sex education (or abstinence) to their children. Documenting parental views on the topic would allow for the development of initiatives that also take into consideration their preferences, and not only the perspectives of young people.

Empirically test the public health effects of comprehensive sex education

It would be pertinent to empirically test and validate the public health effects and efficacy of providing comprehensive sex education to parents of Colombian youth. Previous studies in the United States have shown that involving the family in young people’s sex education can have positive results (Grossman et al., 2013, 2014). One possible option would be to conduct a prospective cohort study. In one geographical region, comprehensive sex education could be provided to parents of adolescents (exposed group) and a neighboring region could be the control group where no sex education is provided to parents. Various outcomes could be measured longitudinally to explore whether providing comprehensive sex education to parents leads to positive health outcomes for young people, e.g., level of access to SRHS and use of contraceptives, adolescent pregnancy rates, and rates of HIV/STI testing.

Limitations

A non-negligible limit of our study is representation bias. The opinions and experiences of the participants might not reflect those of the other youth populations of Colombia (e.g., the Caribbean coast has a different cultural context than the departments of Antioquia and Valle del Cauca). Also, it is important to note that most participants were older, thus younger adolescents (e.g., under 14 years old) might have different views on the topic. While most participants expressed a certain enthusiasm regarding their parents receiving comprehensive sex education to enable better discussion of the topic, this attitude may not be shared amongst the rest of young people in Colombia.

Further, some participants were less at ease expressing themselves during the interviews. The researcher would use keywords to invite participants to develop their answers (e.g., “could you expand or elaborate this idea?”) but some participants still kept their answers short. As a result, the researcher had to reformulate questions to be more direct. For example, if the participant did not know what topic could be part of sex education for their parents, the researcher would present suggestions; the participant could then confirm whether they agreed. In terms of data collection, this can engender a certain bias since the possible answer to the questions were first presented by the researcher as opposed to being generated by the participant.

Finally, another limitation is the potential of desirability bias: some participants might have responded to questions with what they believed to be a “good answer,” or because they wanted to please the researcher, who is not Colombian. Conversely, the fact that the researcher was a foreigner might have helped participants feel more comfortable sharing their beliefs, since the researcher did not belong to the local community and thus could be seen as impartial.

Conclusion

The main goal of this study was to explore issues raised by the fostering of Colombian youth’s autonomy to access SRHS. Through the methodological approach of semi-structured interviews with young people, most participants expressed their wish for their autonomy to be fostered to access SRHS, including (1) the participation of their parents in decision making, and (2) the provision of comprehensive sex education to their parents to facilitate discussions. These findings contradict the initial assumption, based on the literature in different cultural contexts, that participants would not want their parents involved in fostering their autonomy to access SRHS.

There may be specific cultural reasons behind these findings related to young Colombian people (and their parents) that might not apply to other countries or cultural contexts (e.g., North America). Hence, it would be pertinent to do more in-depth research (e.g., interviews) with Colombian parents to further examine the issue. But it would also be pertinent to conduct similar research with young people (and their parents) in other cultural contexts, to see whether there is a need for more nuance in understanding why and how young people may or may not want parental involvement or support in autonomous decision making related to accessing SRHS.

Adolescence is a culturally diverse concept, and adolescent autonomy evolves over time and varies between individuals. Our findings show that fostering adolescent autonomy should be seen as a multi-stakeholder project. With a view to supporting the practical and effective implementation of the WHO’s AA-HA! initiatives to foster young people’s autonomy in access to SRHS, we argue that critically important lessons can be learned when we listen to the voices of both young people and their parents and include them in evidence-based policy making.

Data Availability

Unavailable as per institution’s REB.

References

Adams, W. (2015). Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In K. Newcomer, H. Hatry & J. Wholey (eds.), Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation (4th edition), (pp. 492–505). John Wiley & Sons

Ashcraft, A. M., & Murray, P. J. (2017). Talking to parents about adolescent sexuality. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 64(2), 305–320. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2016.11.002

Atienzo, E. E., Walker, D. M., Campero, L., Lamadrid-Figueroa, H., & Gutiérrez, J. P. (2009). Parent-adolescent communication about sex in Morelos, Mexico: does it impact sexual behaviour? The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 14(2), 111–119

Baldwin, S. E., & Baranoski, M. V. (1990). Family interactions and sex education in the home. Adolescence, 25(99), 573

Bédin, V. (2009). Qu’est-ce que l’adolescence?. Éditions Sciences Humaines

Beh, H. G. (2006). Recognizing the sexual rights of minors in the abstinence-only sex education debate. Children’s Legal Rights Journal, 26(2), 1–20

Blakey, V., & Frankland, J. (1996). Sex education for parents. Health Education, 5, 9–13

Blum, R., & Boyden, J. (2018). Understand the lives of youth in low-income countries. Nature, 554(7693), 435–437. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-02107-w

Boykin McElhaney, K., & Allen, P. A. (2012). Sociocultural perspectives on adolescent autonomy. In P. Kerig, M. Schulz, & S. Hauser (Eds.), Adolescence and beyond: Family processes and development (pp. 161–176). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199736546.003.0011

Brack, C. E., Rochat, R. W., & Bernal, O. A. (2017). “It’s a Race Against the Clock”: a qualitative analysis of barriers to legal abortion in Bogotá. Colombia International perspectives on sexual and reproductive health, 43(4), 173–182. doi: https://doi.org/10.1363/43e5317

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brisson, J., Ravitsky, V., & Williams-Jones, B. (2021a). Colombian Adolescents’ Perceptions of Autonomy and Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Services: An Ethical Analysis. Journal of Adolescent Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/07435584211014862

Brisson, J., Ravitsky, V., & Williams-Jones, B. (2021b). “Fostering Autonomy” for Adolescents to Access Health Services: A Need for Clarifications. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(6), 1038–1039. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.03.007

Byers, E. S., Sears, H. A., Voyer, S. D., Thurlow, J. L., Cohen, J. N., & Weaver, A. D. (2003). An adolescent perspective on sexual health education at school and at home: I. High school students. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 12(1), 19–33

Coenen-Huther, J. (2006). Compréhension sociologique et démarche typologiques. European Journal of Social Sciences, 135, 195–205. https://doi.org/10.4000/ress.272

Colombian Health Ministry (2021). Derechos sexuales y reproductivos para adolescentes y jovenes [Sexual and Reproductive Rights for Adolescents and Young People]. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/salud/publica/ssr/Paginas/Derechos-sexuales-y-reproductivos-para-adolescentes-y-jovenes.aspx (accessed May 28, 2021)

Corrales, J., & Sagarzazu, I. (2019). Not All ‘Sins’ Are Rejected Equally: Resistance to LGBT Rights Across Religions in Colombia. Politics and Religion Journal, 13(2), 351–377. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54561/prj1302351c

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans (4th ed.). Geneva:WHO Press

Crichton, J., Ibisomi, L., & Gyimah, S. O. (2012). Mother–daughter communication about sexual maturation, abstinence and unintended pregnancy: Experiences from an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Adolescence, 35(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.06.008

Diiorio, C., Pluhar, E., & Belcher, L. (2003). Parent-child communication about sexuality: A review of the literature from 1980–2002. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents & Children, 5(3–4), 7–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J129v05n03_02

Evans, R., Widman, L., Kamke, K., & Stewart, J. L. (2020). Gender differences in parents’ communication with their adolescent children about sexual risk and sex-positive topics. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(2), 177–188

Every Woman Every Child. (2015). The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030). Geneva: World Health Organization

Fuentes, L., Ingerick, M., Jones, R., & Lindberg, L. (2018). Adolescents’ and young adults’ reports of barriers to confidential health care and receipt of contraceptive services. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(1), 36–43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.10.011

Galletta, A. (2013). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research design to analysis and publication. New York: NYU press

Garside, R., Ayres, R., Owen, M., Pearson, V. A., & Roizen, J. (2002). Anonymity and confidentiality: Rural teenagers’ concerns when accessing sexual health services. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health, 28(1), 23–26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1783/147118902101195965

Gaudet, S., & Robert, D. (2018). L’aventure de la recherche qualitative: Du questionnement à la rédaction scientifique. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press

Grossman, J. M., Frye, A., Charmaraman, L., & Erkut, S. (2013). Family homework and school-based sex education: delaying early adolescents’ sexual behavior. Journal of School Health, 83(11), 810–817. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12098

Grossman, J. M., Tracy, A. J., Charmaraman, L., Ceder, I., & Erkut, S. (2014). Protective effects of middle school comprehensive sex education with family involvement. Journal of School Health, 84(11), 739–747. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12199

Irvine, J. (2002). Talk About Sex: The Battles Over Sex Education in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press

Israel, B. A., Coombe, C. M., Cheezum, R. R., Schulz, A. J., McGranaghan, R. J., Lichtenstein, R., & Burris, A. (2010). Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 100(11), 2094–2102. doi: https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506

Jerman, P., & Constantine, N. A. (2010). Demographic and psychological predictors of parent–adolescent communication about sex: A representative statewide analysis. Journal of youth and adolescence, 39(10), 1164–1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9546-1

Kakavoulis, A. (2001). Family and sex education: a survey of parental attitudes. Sex Education, 1(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810120052588

Kohler, P. K., Manhart, L. E., & Lafferty, W. E. (2008). Abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education and the initiation of sexual activity and teen pregnancy. Journal of adolescent Health, 42(4), 344–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.026

Kon, A. A. (2009). The role of empirical research in bioethics. The American Journal of Bioethics, 9(6–7), 59–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15265160902874320

Lawrence, R. E., Rasinski, K. A., Yoon, J. D., & Curlin, F. A. (2011). Adolescents, contraception and confidentiality: a national survey of obstetrician–gynecologists. Contraception, 84(3), 259–265. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2010.12.002

Ledford, H. (2018). Who exactly counts as an adolescent? Nature, 554, 429–431. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-02169-w

Lehrer, J. A., Pantell, R., Tebb, K., & Shafer, M. A. (2007). Forgone health care among US adolescents: associations between risk characteristics and confidentiality concern. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(3), 218–226. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.015

Mabaso, Z., Erogbogbo, T., & Toure, K. (2016). Young people’s contribution to the Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health (2016–2030). Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 94(5), 312–312. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.174714

Mahajan, P., & Sharma, N. (2005). Parents attitude towards imparting sex education to their adolescent girls. The Anthropologist, 7(3), 197–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2005.11890907

Maher, C., Hadfield, M., Hutchings, M., & de Eyto, A. (2018). Ensuring rigor in qualitative data analysis: A design research approach to coding combining NVivo with traditional material methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918786362

Malacane, M., & Beckmeyer, J. J. (2016). A review of parent-based barriers to parent–adolescent communication about sex and sexuality: Implications for sex and family educators. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 11(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2016.1146187

Mazur, A., Brindis, C. D., & Decker, M. J. (2018). Assessing youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services: a systematic review. BMC health services research, 18(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2982-4

Minkler, M., Blackwell, A. G., Thompson, M., & Tamir, H. (2003). Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. American Journal of Public Health, 93(8), 1210–1213. doi: https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210

Moran, J. P. (2002). Teaching sex: The shaping of adolescence in the 20th century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

Mullis, M. D., Kastrinos, A., Wollney, E., Taylor, G., & Bylund, C. L. (2021). International barriers to parent-child communication about sexual and reproductive health topics: a qualitative systematic review. Sex Education, 21(4), 387–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2020.1807316

Muntean, N., Kereta, W., & Mitchell, K. R. (2015). Addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of young people in Ethiopia: an analysis of the current situation. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 19(3), 87–99

Nambambi, N. M., & Mufune, P. (2011). What is talked about when parents discuss sex with children: family based sex education in Windhoek, Namibia. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 15(4), 120–129

Nature. (2018). Adolescence research must grow up. Nature, 554, 403. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-02185-w

Ogle, S., Glasier, A., & Riley, S. C. (2008). Communication between parents and their children about sexual health. Contraception, 77(4), 283–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2007.12.003

Orji, E. O., & Esimai, O. A. (2003). Introduction of sex education into Nigerian schools: the parents’, teachers’ and students’ perspectives. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 23(2), 185–188. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0744361031000074772

Paillé, P., & Mucchielli, A. (2012). L’analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales (3rd edition). Paris: Armand Colin

Pampati, S., Liddon, N., Dittus, P. J., Adkins, S. H., & Steiner, R. J. (2019). Confidentiality matters but how do we improve implementation in adolescent sexual and reproductive health care? Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(3), 315–322. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.03.021

Parker, R. (2009). Sexuality, culture and society: shifting paradigms in sexuality research. Culture Health & Sexuality, 11(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050701606941

Patton, G. C., Sawyer, S. M., Santelli, J. S., Ross, D. A., Afifi, R., Allen, N. B., Arora, M., Azzopardi, P., Baldwin, W., Bonell, C., Kakuma, R., Kennedy, E., Mahon, J., McGovern, T., Mokdad, A. H., & Viner, R. M. (2016). Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet, 387(10036), 2423–2478. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1Patel, Vikram, Petroni, Suzanne, Reavley, Nicola, Taiwo, Kikelomo

Patton, G. C., Coffey, C., Cappa, C., Currie, D., Riley, L., Gore, F., & Ferguson, J. (2012). Health of the world’s adolescents: a synthesis of internationally comparable data. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1665–1675. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60203-7

Pilcher, J. (2004). Sex in health education: official guidance for schools in England, 1928–1977. Journal of Historical Sociology, 17(2-3), 185–208

Pope, C., Van Royen, P., & Baker, R. (2002). Qualitative methods in research on healthcare quality. BMJ Quality & Safety, 11(2), 148–152. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.11.2.148

Prada, E., Singh, S., Remez, L., & Villarreal, C. (2011). Embarazo no deseado y aborto inducido en Colombia: causas y consecuencias. Guttmacher Institute

Robinson, K. H., Smith, E., & Davies, C. (2017). Responsibilities, tensions and ways forward: Parents’ perspectives on children’s sexuality education. Sex Education, 17(3), 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2017.1301904

Sankar, P., & Jones, N. L. (2007). Semi-structured interviews in bioethics research. In L. Jacoby, & L. A. Siminoff (Eds.), Empirical methods for bioethics: A primer (pp. 117–136). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-3709(2007)11

Sawyer, S., & Patton, G. (2018). Health and Well-Being in Adolescence. In J. Lansford, & P. Banati (Eds.), Handbook of Adolescent Development Research and Its Impact on Global Policy (pp. 28–45). Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190847128.003.0002

Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

Schalet, A. (2004). Must we fear adolescent sexuality? Medscape General Medicine, 6(4), 44

Shtarkshall, R. A., Santelli, J. S., & Hirsch, J. S. (2007). Sex education and sexual socialization: Roles for educators and parents. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health, 39(2), 116–119. https://doi.org/10.1363/3911607

Trinh, T., Steckler, A., Ngo, A., & Ratliff, E. (2009). Parent communication about sexual issues with adolescents in Vietnam: content, contexts, and barriers. Sex Education, 9(4), 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810903264819

UN. (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations

UNESCO. (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach. Geneva: World Health Organization

Vandermorris, A., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2017). How Canada can help global adolescent health mature. Reproductive health, 14(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0353-y

Vujovic, M., Struthers, H., Meyersfeld, S., Dlamini, K., & Mabizela, N. (2014). Addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of young adolescents living with HIV in South Africa. Children and Youth Services Review, 45, 122–128. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.028

Walker, J. L. (2001). A qualitative study of parents’ experiences of providing sex education for their children: The implications for health education. Health Education Journal, 60(2), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/001789690106000205

Walker, J. (2004). Parents and sex education—looking beyond ‘the birds and the bees’. Sex Education, 4(3), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/1468181042000243330

WHO. (2014). Adolescence: A period needing special attention. Health for the World’s adolescents report. Geneva: World Health Organization

WHO. (2017). Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation. Geneva: World Health Organization

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants that volunteered to participate in the research. The authors would also like to thank the employees at Profamilia who helped put the research in place, especially Claudia Patricia Perez.

Funding

This work was supported by the author’s Canadian Doctoral Award to Honour Nelson Mandela awarded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [201610GSD-385545-283387].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure statement

No conflict of interests to declare.

Ethical Evaluation

The University of Montreal’s Research Ethics Committee first evaluated and approved the research project, then the research project was evaluated and approved by the Profamilia’s research ethics committee (which included a lawyer).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Brisson, J., Ravitsky, V. & Williams-Jones, B. Colombian Youth Express Interest in Receiving Sex Education from their Parents. Sexuality & Culture 27, 266–289 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-022-10012-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-022-10012-8