Abstract

In Western society sex appeal has become greatly valued and young women actively and publically expose their sexualities in a variety of ways. Those women who embrace and participate in the hyper-sexualized cultural trend are called self-sexualizers. Despite the growing number of empirical studies related to self-sexualization, there is lack of consensus around a definition of self-sexualization among researchers. The concept of self-sexualization needs to be clarified and explained. The primary purpose of this examination is to address the self-sexualizing phenomenon and to define self-sexualization by building upon previous researchers’ approaches. In this research, self-sexualization is defined as the voluntary imposition of sexualization to the self. We adapted the four aspects of sexualization presented in a task force report issued by the American Psychological Association in 2007 to propose the four conditions of self-sexualization. (1) The first condition of self-sexualization is favoring sexual self-objectification. (2) The second condition is relating sexual desirability to self-esteem. (3) The third condition is equating physical attractiveness with being sexy. (4) The last condition is contextualizing sexual boundaries. Description of each condition and related concepts are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In a Western society where “sex appeal has become a synecdoche for all appeal” and sex appeal has become greatly valued (Levy 2006, p. 30), active and public exposure of one’s sexuality is common, especially among young women (Nowatzki and Morry 2009). This active exposure of sexuality includes a range of behaviors such as women wearing low cut cleavage-revealing tops, crop-tops that emphasize midriffs, or tops with exposed backs that enable exposure of undergarments if worn. This active exposure is not limited to adult women. Everyday wear for many adolescent girls includes t-shirts emblazoned with phrases such as “up for it” and pants labeled “juicy” or “delicious” across their buttocks.

Improving one’s personal attractiveness has been an ongoing societal value and occurs in most cultures, but the current trend, especially in Western society in which attractiveness is synonymous with increasing sexual appeal, deserves exploration (Levy 2006, p. 30). For example, how is this trend reflected in people’s values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors? Some women attend pole dance classes or “cardio striptease” classes that are offered through fitness centers and marketed as empowering (Whitehead and Kurz 2009). Some people admire female models who gain notoriety primarily through their display of huge breast implants (Walter 2011) and believe that being sexual results in both social power and popularity (Erchull and Liss 2013).

Is there a difference in empowering and social power, and in the private and public exposure that results? Private acts that empower the self are one outcome that may be considered desirable; but public exposure that brings popularity may also bring unwanted attention to young girls who do not understand the possible consequences. For example, it is not difficult for the crews of the television series, “Girls Gone Wild” to find college women eager to roll up their shirts to flash their breasts for the camera (Levy 2006). Spreading nude self-portrait pictures (i.e., nude selfies) via photo texts has gained popularity among young adults as well as teenagers (Ferguson 2011). These are examples of girls seeking to self-sexualize that could result in unwanted, unanticipated, or undesirable outcomes such as sexual objectification that could result in risk from observers misinterpreting the intention based upon their own perspective.

Researchers have long been interested in investigating the influence of relentless and ubiquitous sexual messages upon culture. Particularly, since the American Psychological Association’s task force report on the sexualization of girls (2007), researchers are increasingly examining the concept of self-sexualization, that is, treating and experiencing oneself as a sexual object (APA 2007). However, despite the growing number of empirical studies related to self-sexualization (e.g., Liss et al. 2011; Nowatzki and Morry 2009; Ward et al. 2018; Whitehead and Kurz 2009; Ramsey et al. 2017), there is lack of consensus around a definition of self-sexualization among researchers. The concept of self-sexualization needs to be clarified. Accordingly, the primary purposes of this examination are to address the self-sexualizing phenomenon and to define self-sexualization by building upon the approaches of previous researchers.

Literature Review

The focus of this research is self-sexualization by members of the general public who participate in the highly sexualized cultural trend. Although self-sexualization can occur for both men and women regardless of one’s sexual identity, this study focuses on self-sexualization of women because the current phenomenon predominantly occurs among women. Probably for that reason, existing studies on the topic have mainly dealt with female self-sexualization. The evidence of a highly sexualized cultural trend is becoming increasingly apparent in several countries across the world (e.g., a pole dancing class offered to the public in South Korea). However, research on the sexualized culture has focused on relatively affluent Western society to the exclusion of non-Western society. Accordingly, the focus of this study is on Western society with plans for expanding the research to non-Western society in the future. Because little is known about any potential cross-cultural differences, literature was introduced regardless of a specific culture.

Hyper-Sexualized Cultural Phenomenon

Journalists and scholars have noted the mainstreaming of both soft-core and hard-core pornography as a cultural trend (Nowatzki and Morry 2009). They seem to agree on the idea that the Western society has become extremely sexualized, in other words, hyper-sexualized (e.g., Attwood 2009; Kammeyer 2008; Levy 2006; Lynch 2012; McNair 2002; Walter 2011). They have introduced several terms to describe this phenomenon. For example, McNair (2002) used “pornographication” and “porno-chic” to refer to the representation of pornography in mainstream art and within the culture. Levy (2006) used the phrase “raunch culture” to describe the increasing popularity of pornography within mainstream culture. Lynch (2012) used the term “porn chic” to describe stylized pornographic imagery for young women. This stylized pornographic sexual imagery in mainstream culture is different from traditional pornography. The stylized pornographic sexual imagery is often staged and the performance is often celebrity-led (e.g., sex scenes in the Madonna’s music video Justify My Love) while traditional pornography contains a real sexual act that is depicted by relatively unknown individuals (McNair 2002).

While some researchers have grouped this trend into a broad category of behavior [e.g., Levy’s (2006) raunch culture; Lynch’s (2012) porn chic], McNair (2002) distinguished two hyper-sexualized cultural trends, excluding real pornography. One was the pornographic sexiness generated by professionals (e.g., actors, artists, filmmakers) and the other was sexiness generated by the behavior of members of the general public. Although sexual imagery within mainstream culture may have begun earlier, the staged celebrity-led pornographic sexiness became evident in the early 1990s (Attwood 2009; McNair 2002). Some of the first signs were the appearance of celebrities naked or sexualized in popular media. For example, Demi Moore posed naked during pregnancy for the cover of a 1991 issue of Vanity Fair, a popular magazine. In the following year, she appeared wearing only body paint. Indeed the practice gained momentum so quickly that it became relatively easy to locate celebrities, including athlete celebrities, appearing nude, near nude, or in sexualized appearances in almost every magazine (McNair 2002). Madonna’s book, Sex, published in 1992 is another example. In her book images and simulations of sex acts, including sadomasochism and analingus, were featured as stylized and edited by a fashion magazine editor and photographer. At about the same time, Madonna released her fifth music album, Erotica.

Coincidently, the porn industry found its way into mainstream culture. While celebrities mimic pornographic sexuality, the porn industry was destigmatized and porn starts gained cultural acceptance. Sarracino and Scott (2008) described the shift of individuals who performed sexual acts in the early porn films (they were usually prostitutes) to entertainers acting in scripted movies in the twenty-first century. Porn stars had become celebrities who were not only accepted but also even admired and exemplified by the public. For example, an autobiography of a porn star, How to make love like a porn star, was a bestseller, disregarding that sexuality presented in porn materials is exaggerated and manufactured for money. Porn stars write bestselling books and give advice on sex life for lifestyle magazines (Attwood 2009).

Another hyper-sexualized cultural trend identified by McNair (2002) was the pornographic sexiness participated in by members of the general public, the ordinary Joe or Jane. The focus of this study is ordinary people who take active roles in the hyper-sexualized culture, as McNair identified. McNair (2002) used the term “striptease culture” to describe the so-called democratization of sexual self-exhibition and bodily exposure and introduced it as “a sub-set of a broader sexualization of mainstream culture” (p. 81). Members of the general public participate in the hyper-sexualized cultural trend in several ways.

One way is to be a supportive and enthusiastic consumer of sexualized media content. Evidence of the public’s interest and support of sexualized content comes from the popularity of these images and increases in monetary rewards received by those celebrities who are willing to sell their sexuality or use it to market other products. Referencing the earlier example of Demi Moore posing naked on a magazine cover, compared to her earnings in 1990, her earnings rose eight and one-half times in 1992 (Davies 2012). The 1992 issue of Vanity Fair with Demi Moore posing in body paint sold 63% more copies than the other 11 issues of the same year, as IMDb.com described in Demi Moore’s biography. Madonna’s book, Sex, appeared on the New York Times Best Seller list on November 8, 1992, and sold over 150,000 copies on the first day of its release. Consumer’s favorable reaction to sexualized content has continued. There are some female celebrities who gained popularity primarily due to their amateur pornographic videos (e.g., Paris Hilton, Kim Kardashian) or large breast implants (e.g., Pamela Anderson).

In addition to being supportive consumers, members of the general public participate in the hyper-sexualized cultural trend as active creators or performers of the hyper-sexiness. These behaviors include sexual self-exhibition and bodily exposure. People may model the sexualized imagery located in the media as well as create independent sexualized content (e.g., amateur pornography videos). They also may live hyper-sexualized lives as a lifestyle choice (e.g., engage in the hook-up culture). For example, women participate in professional boudoir photography or pinups, flash their breasts at public events, and manage their appearance to feature mainstream pornography (e.g., wearing T-shirts labeled “porn star”, dressing like prostitutes for Halloween).

Contributors to the Phenomenon

Being either a supportive consumer or an active creator of the hyper-sexualized cultural trend, self-sexualizing women partake of the culture through voluntary acceptance or by internalization of the imposed obligations from the outside. Although a systematic analysis of how women became active subjects of self-sexualization is beyond the scope of this paper, we attempt to present some of the explanations for the phenomenon where women embrace the hyper-sexualized cultural trend.

Media. One of the commonly addressed influencers is the media. The media often manufactures artificial images of female beauty and the viewers are cultivated to uphold the ideal beauty. Ward (2016) documented the breadth of empirical research examining the effect of sexually objectifying portrayals of women in mainstream media. By examining 109 studies, Ward revealed the direct effects of media on a range of consequences (e.g., greater self-objectification and body dissatisfaction, higher levels of sexist beliefs and tolerance of sexual violence). One of the consequences is the increase in the internalization of the perspectives of an observer, manifested by constant monitoring of one’s appearance. Ward et al. (2016, 2018) continued their research on the media influences, in particular, on self-sexualization. Their findings showed that media exposure (e.g., reality programs romantic-themed movies, women’s magazines, sitcoms) was a significant predictor of the higher degree of self-sexualization. The more participants were exposed to the media with highly sexualized portrayals, the more they objectify their own bodies, enjoy emphasizing their sexiness, and base their worth on sexual appeal.

The influence of media can be explained by Gerbner’s cultivation theory (1972). Cultivation theory discusses television’s influences on viewers’ beliefs and attitudes. According to the theory, spending a large amount of time living in virtual reality by watching television contributes to viewers’ conception of social reality. Unlike a short-term effect, the viewers’ conception grows or is cultivated in the process of massive and long-term exposure to television reality. Thus, heavy exposure to a sexualized female image in the media encourages viewers to accept the sexualized imagery as a true representation of reality. Exposure to the celebrities who gained popularity from their highly sexualized images and performances (e.g., Madonna, Kim Kardashian) also cultivate the views’ conception of their personal sexual realm. The cultivation theory also argues that this cultivation process will heighten when individuals’ direct everyday experience is congruent with the virtual reality presented on television. For example, let us imagine that a person who witnesses a woman appearing in body-revealing dress receives free merchandise in real life. Then that person watches a television scene where a woman in body-revealing dress successfully evades a speeding ticket. In this example, the person’s real life experience was congruent with the virtual reality on television. If this were the case, the cultivation process would be strengthened because of the close fit between real life and virtual life.

Peer Peer influence and peer context are other explanations of self-sexualization. In a study of the female flashing behavior where women either take off or roll up their shirts to show their breasts in a homecoming celebration (Lynch 2007), the female flashers reported that their flashing behavior was unplanned, influenced by alcohol, and most often pressured or forced by peers. Among the interviewed female students (n = 37), nine of them had flashed at least once during a homecoming celebration; eight of them had been pressured to flash; ten of them were with a friend who flashed, and ten of them observed flashing behavior by others. However, male participants of the homecoming celebration indicated that they believed the women came to the site planning to flash. All flashers reported having negative feelings about their behavior after flashing. They also recalled violent force used by men. Yet, most of the flashers had engaged in flashing behavior more than once.

Similar to the flashing behavior, the presence of peer influence and peer pressure was found on the range of other self-sexualizing behaviors. For example, in a study of performative same-sex sexual behavior (e.g., kissing one other) among heterosexual women, women reported that they felt the specific pressure to perform bisexuality to entertain or induce arousal of male audiences at parties or bars (Fahs 2009; Yost and McCarthy 2012). Peer influence and peer pressure were the same for younger women. Adolescent girls sometimes felt pressured to send their sexually provocative pictures (i.e., sexting) to their boyfriends (Ouytsel et al. 2017b). For them, whether or not their peers would approve of sexting was a significant factor accompanying their sexting behavior (Ouytsel et al. 2017a). Talking with friends about appearance related topics on a social network site was also found to be a significant direct predictor of self-sexualizing behaviors, such as wearing low-cut shirts that show cleavage and wearing low-rise pants that show underwear (Trekels et al. 2018).

Positive feelings Positive feelings experienced from self-sexualization may contribute to the behaviors. In the case where a woman is successful in sexually enticing a man’s attention, she may feel that she is approved, appraised or admired by the man. As a matter of fact, she will probably be well treated by men (Sigall and Landy 1973; Snyder et al. 1977); because, in general, attractive people are treated favorably in various situations, such as in performance evaluation (Landy and Sigall 1974), in hiring (Cash and Kilcullen 1985), and in selecting a dating partner (Walster et al. 1966). In the aforementioned study of flashing behavior (Lynch 2007), some participants talked about feelings of being accepted, popular, and special as a result of their flashing.

In addition, a woman who successfully attracts a man may feel that she is in control. Ronai and Ellis (1989) conducted a study with women who stripped for a living (e.g., women who intentionally displayed themselves as sexual objects for work). Researchers reported that some dancers enjoyed the feeling of “conquering and being in control”, while others felt “degraded and out of control” (p. 282). Similar responses were reported in a study with employees at Hooters, a restaurant where female employees are active in sexually objectifying themselves for higher tips (Moffitt and Szymanski 2011). Some women reported that their self-confidence and self-esteem increased and they became outgoing as a result of working in the environment. Others reported uncomfortable experiences from receiving “powerful contradictory messages and felt unable to act on either” (p. 78) and experiencing a “bad vibe” and “creepy” feeling from customers (p. 85). Some researchers argued that adolescent girls also may experience positive feelings; Peterson (2010), in her work with adolescent girls, argued that women may experience empowerment when they attract attention with sexuality.

Even though some women reported that they felt “good”, “in control”, or “enjoyed” being sexually objectified from self-sexualization, these positive feelings were not necessarily long-lasting. This raises the question of whether it is possible that those feelings resulted from a sense of false empowerment (Liss et al. 2011). When women voluntarily become a sexual object, they may feel they have the power to evoke men’s positive judgments and desire while men have the power to judge (Lynch 2012). Women’s feelings of empowerment are granted by men through receiving approving looks, attention, and complimentary comments on their appearance, but only if their physical appearance conforms to narrowly defined standards (APA 2007). In fact, a study revealed that women who enjoyed self-sexualization were more likely to feel objectified by their partners, which lead to lower relationship satisfaction (Ramsey et al. 2017).

Normalized porn In addition, rampant online pornography and the prevalence of pornographic images may explain the endorsement of self-sexualization. Access to pornography became increasingly easy since the early 1970s; adult erotic films were released in theaters and several adult cable channels (e.g., Playboy Channel, Spice Channel) were available at home (Sarracino and Scott 2008). Due to the Internet, access to pornography has become significantly easier via personal computer devices. It has become so easy (and some of it is free) that even adolescent boys and the majority of adolescent girls have reported watching online pornography (Sabina et al. 2008). People use pornography as one of the sources for sexual information and sex education, neglecting to realize that it rarely shows safer sex (Philpott et al. 2017).

One of the recent trends of body modification in a hyper-sexualized culture is female genital cosmetic surgery and it is often inspired by pornography. This surgery includes a range of procedures primarily to produce genitalia that have an aesthetically pleasing appearance (e.g., labiaplasty, perineoplasty, vaginoplasty) and referred to as designer vaginas (Braun 2005). Previously, female genital cosmetic surgery was done primarily by sex workers and nude models, or women for medical reasons due to infection or pain. However, these procedures have become increasingly popular among women for aesthetic purposes (Goodman 2011). Lynch (2012) explained that this trend of having female genital cosmetic surgery is due to the women who admire pornographic images. In a study about female pubic hair removal, some women compared their genitals to those in pornography and expressed dissatisfaction with their vaginas (Fahs 2014).

When it comes to pubic waxing, there are several options (Morris 2004): the bikini line, the full bikini, the European, the triangle, the mustache, the heart, the landing strip, the Playboy strip, the Brazilian wax, and the Sphynx. The Playboy strip is named after the soft-porn Playboy magazine because the wax style was featured by the magazine’s models (Labre 2002). The Brazilian wax in particular (i.e., complete removal of hair on genital area including labia and anus) is often compared to body alteration in achieving the appearance of porn stars in pornography who completely shave their pubic hair for detailed genitalia shots (Jeffreys 2005).

In the next section, concepts that are relevant to understanding self-sexualization are addressed to reduce the conceptual murkiness between the terms. The most commonly cited definition of self-sexualization (APA’s definition 2007) is introduced and its limitation is addressed. Then, a new conceptualization is presented with four conditions that supplement the missing elements in the previous definition.

Conceptualization of Self-Sexualization

There are four relevant concepts to understanding self-sexualization: objectification, sexual objectification, sexualization, and self-objectification. Among these concepts, we adopted sexualization as the key concept that is directly related to defining self-sexualization. Because sexualization serves as the reference point in defining self-sexualization, the definition of sexualization needs to be presented before differentiating the other concepts.

Sexualization and Self-sexualization by APA (2007)

The APA (2007) task force identified four conditions of sexualization. Any one of these four conditions is sufficient for sexualization to occur. (1) The first condition of sexualization is when a person is viewed as an object for others’ sexual use. (2) The second condition of sexualization occurs when a person is held to a standard that equates physical attractiveness with being sexy. (3) The third condition is when a person’s value comes from his or her sexual appeal or behavior. (4) The fourth condition of sexualization occurs when sexuality is inappropriately imposed upon a person. In the same report, the APA (2007) task force defined self-sexualization as treating and experiencing oneself as a sexual object. This definition of self-sexualization, however, captures only one of the four conditions where sexualization is believed to occur: the first sexualization condition where a person is viewed as an object for another’s sexual use. Having these definitions in mind, the other key concepts are explained in the following section.

Conceptual Murkiness: Objectification, Sexual Objectification (Sexualization), Self-objectification, and Self-sexualization

Scholars have addressed some of the conceptual murkiness between objectification, sexual objectification, sexualization, self-objectification and self-sexualization (e.g., Gervais et al. Allen 2013; Zurbriggen 2013). Although these concepts may sound similar, they are conceptually distinct from each other, with little overlap. Treating others as objects (objectification), treating others as sexual objects (sexual objectification; often interchangeably used with sexualization), and thinking of oneself as an object (self-objectification) are related to understanding what it means to treat or experience oneself as a sexual subject with a favorable attitude (self-sexualization). Definitions of concepts related to self-sexualization are summarized in Table 1.

Objectification. Objectification of a human being is the condition or process of degrading a human to the status of a physical thing (Nussbaum 1995). Nussbaum presented seven notions that are involved in the objectification of humans which include instrumentality, fungibility, and instrumentality. For example, if employers objectify their employees, they regard them as tools who exist primarily for the purpose of employers’ benefits. Similar to the mechanical parts of a car, objectified employees might be considered as resource objects that are easily replaceable and changeable. When an individual is objectified, his or her feelings, emotions, and experiences are excluded when relating to that individual. [See Nussbaum (1995) for detailed explanations of objectification with the seven notions.]

Sexual objectification While objectification occurs when a human being is treated like a thing instead of as a thinking, and feeling being (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997; Nussbaum 1995), sexual objectification occurs when a person’s sexual parts or functions are separated from the person, reduced to the status of mere instruments, or else regarded as if they were capable of representing the person (Bartky 1990, p. 35). This definition contains two of four conditions of sexualization (APA 2007). Later, Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) recited this definition making a slight change from “sexual parts or functions” to “body, body parts, or sexual functions” (p. 175) in their research on self-objectification. When Bartky (1990) and Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) described sexual objectification, they focused on the sexual objectification of women only.

The definition of sexual objectification has two features: detachment of body parts (or sexual parts) from a person and the representability of body parts or functions of body parts for the person. The first feature of sexual objectification may lead to all seven notions of objectification (degrading a human to the status of a physical thing; for details, see Nussbaum 1995). For example, when a body is treated as a physical thing, the body can be used as a tool for another’s sexual purpose—either decorative for the purpose of sexual arousal or for a functional purpose (e.g., masturbation). Also, the body can be interchanged with other non-human alternatives such as sex toys. When the body is interchanged with other non-human alternatives for a sexual purpose, this case of sexual objectification is directly related to the first condition of sexualization identified by the APA (2007): A person is sexually objectified.

The second feature of sexual objectification, the representability of body parts or function of body parts for the person shares similarity with the third condition of sexualization (APA 2007). If a person is degraded by another to the level of a body part as if the body part alone has the most value to the exclusion of other characteristics of an individual, this practice reflects the idea of a person’s value coming primarily from her sexuality or sexual appeal (the third condition of sexualization). For example, a person may treat a woman with favor because of her erotic appearance.

Sexual objectification defined by Bartky (1990) and Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) contains the first and the third conditions of sexualization by APA (2007). The two remaining conditions (a person is held to a standard that equates physical attractiveness with being sexy; sexuality is inappropriately imposed upon a person) are not captured in its definition. However, sexual objectification is often used interchangeably with the term sexualization. Sexual objectification or sexualization has received tremendous attention from scholars, particularly feminist scholars who scrutinize sexual objectification of women as a vital part of sexism that obstructs gender equality (Zubriggen 2013). Sexualization of women occurs in a range of realms, such as media (Ward 2016), music videos and music lyrics (APA 2007), advertisement (Jhally and Kilbourne 2010), and pornography (e.g., Klaassen and Peter 2015).

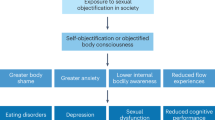

Self-objectification. Constant sexualization is generally considered as a primary environmental antecedent to internalization of sexually objectified experiences (Calogero et al. 2011). This internalization of sexually objectified experiences is named self-objectification (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Self-objectification is a concept from objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997), that was proposed as a framework for understanding the consequences of being women in a culture in which the female body was sexually objectified. The theory posited that when women experience constant sexual objectification, they internalize such experiences. When internalization happens, women begin to see themselves as objects to be looked at and evaluated based on their appearance. The authors have termed this internalization of objectification as self-objectification. They argue that one of the primary results of self-objectification is constant body monitoring, in other words, self-surveillance. Self-objectification also results in individuals placing greater emphasis on their physical appearance than on their physical and mental competencies. Emphasis on physical appearance outcomes of self-objectification can also include feelings of body shame and anxiety, reduced opportunities to be fully absorbed in one’s activities, and decrease in awareness of internal bodily states. These negative experiences may also contribute to mental health problems such as depression, sexual dysfunction, and eating disorders. [See Calogero et al. (2011) for a systematic review of self-objectification in women.]

Self-sexualization As self-objectification may be confused with the concept of self-sexualization, self-imposed sexual objectification, it is important to compare the two concepts. The APA definition of self-sexualization is comparable to the concept of self-objectification. While the APA definition of self-sexualization was inspired by Fredrickson and Roberts’s (1997), the definition of self-objectification was inspired by Bartky’s (1990) definition of sexual objectification. Both concepts are similar in their conceptual definitions. The definition of each concept contains the notion of objectification of the self—one refers to seeing oneself as an object from an observer’s perspective (i.e., self-objectification), while the other refers to treating of oneself as a sexual object to be used by others (i.e., self-sexualization according to APA). For example, if a self-objectifier places importance on physical attractiveness (e.g., symmetrical features), a self-sexualizer may place greater emphasis on sexual attraction (e.g., large breasts). However, it is possible that the “object” in the definition of self-objectification includes a sexual component because the theory of self-objectification claims internalization of experiences wherein a person is treated as a sexual object. In one way, the concept of self-objectification is broader than self-sexualization for it includes general appearance, while self-sexualization has a focus limited to sexuality. However, when seen another way, self-objectification is narrower than self-sexualization because it does not include, as self-sexualization does, three other conditions. Thus, Ward et al. (2016) noted self-objectification as a component of self-sexualization. They also acknowledged that, although the definition of self-sexualization focuses on beliefs, the self-sexualizing beliefs manifest in a range of behaviors.

There is another approach in differentiating the two concepts. Allen (2013) made a meaningful distinction between self-objectification and self-sexualization by conceptualizing self-sexualization as behavior. Allen defined self-sexualization as “any action taken by an individual, which intentionally highlights his or her sexualized features” (Allen and Gervais 2012, p. 81). Allen described self-sexualization as a self-presentation strategy wherein one’s body is used to influence other’s opinion of the self and it allows differentiating the self from other women. Similarly, Smolak et al. (2014) operationalized self-sexualization as behaviors that refer to personal hygiene and grooming activities engaged into appear sexually appealing. Aubrey et al. (2017) also operationalized the term as willingly engaging in sexualizing behaviors to encourage a sexualizing gaze, but they recognized self-sexualization with the implicit “intention, or at least the appearance of intention, to adhere to the system of beliefs underlying sexualization where sexual appeal is prioritized and having other people see one as sexually desirable is a primary goal. (p. 363)” In contrast to self-sexualization, self-objectification is a belief that one’s outward appearance is regarded as more important than one’s competence due to internalization of an outsider’s view of the self and viewing oneself as an object (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997).

The difference between self-objectification and self-sexualization also comes from its theoretical precursors. According to self-objectification theory, sexual objectification is a precondition of self-objectification. A woman adopts the objectified view, when she is constantly exposed to environments where women are sexually objectified, either directly (e.g., staring) or indirectly (e.g., watching a music video where a person is portrayed as a decorative sexual object). The theory does not distinguish possible positive experiences from sexual objectification (e.g., feelings of acceptance or being desired by men) from negative experiences. Regardless of whether the experience was positive or negative to her, she internalizes the sexually objectified experience.

In case of self-sexualization, however, the precondition of self-sexualization is yet in active discovery stage by several researchers (e.g., Nowatzki and Morry 2009; Ward et al. 2016; Ward et al. 2018). According to the APA (2007), it is the desire for social approval and benefits derived that motivates women to self-sexualize. The APA (2007) claimed that a person internalizes the socially accepted and approved standards of sexiness when that person learned that sexualized behavior and appearance is rewarded by society overall as well as by close others (e.g., peers). Women may receive the benefits from self-sexualization directly from their own experiences (e.g., avoid punishment, such as a ticket, when she sexually exposes herself) or indirectly through the media (e.g., watching a celebrity receive approval as a result of her sexual appeal). Yet, this claim still needs empirical evidence in order to be conclusively supported. Other possible precursors were addressed in the contributors to hyper-sexualized cultural phenomena.

Defining Self-sexualization with Four Conditions

The APA’s (2007) definition of self-sexualization is the most commonly and widely referred to definition of self-sexualization. However, it only captures one of the four conditions of sexualization by APA (2007). As an attempt to include most of the conditions of sexualization, Hall et al. (2012) in their definition of self-sexualization noted that self-sexualization is not only present in situations where a person is presenting herself as an object for another’s sexual use but also when a woman assumes “that her individual value comes primarily from her sexual appeal and behavior” and when a woman assumes “that her sexiness is equivalent to a narrowly defined level of attractiveness” (p. 3). This definition captures three out of four conditions of sexualization. However, the last situation wherein sexuality is inappropriately imposed upon a person was still not included when defining self-sexualization. Similarly, Ward et al. (2016, 2018) considered the three conditions of sexualization imposed on the self, leaving out the last condition.

Hall et al. (2012) as well as Ward et al. (2016, 2018) may not have included this last condition of sexualization because the essence of self-sexualization is subjectification of one’s sexuality by one’s own choice, unlike a condition of sexualization where sexual objectification is imposed by others. In the same vein, both Gill (2008) and Attwood (2009) described self-sexualization as sexual subjectification and explained the alteration from sexual objectification where women had no agency to sexual subjectification where playfulness, freedom, and choice are present. A woman who voluntarily engages in self sexual objectification, is real self-sexualization.

Along the lines of the previous researchers who attempted the same approach in defining self-sexualization, we attempt to include all of the APA’s four aspects of sexualization as defining conditions of self-sexualization (Table 2). We define self-sexualization as the voluntary imposition of sexualization to the self, consistent with how Ward and her colleagues defined the term (i.e., sexualization beliefs imposed on the self; Ward et al. 2016, 2018). Because the previous studies lack in providing the description of each condition, we illustrated each condition of self-sexualization in this paper. As per the reasoning of members of the APA, any one of four conditions of self-sexualization is sufficient for an individual to be viewed as engaged in self-sexualizing behavior. Accordingly, an individual who is involved in at least one of the four self-sexualization conditions is referred to as a self-sexualizer.

Condition 1: Favoring Sexual Subjectification

The first condition of sexualization by APA (i.e., a person is sexually objectified) was adopted in defining self-sexualization by several researchers (APA 2007; Hall et al. 2012; Ward et al. 2016, 2018). Unlike APA’s (i.e., treating and experiencing oneself as a sexual object) and Hall, West, and McIntyre’s (i.e., thinking of oneself as an object for other’s sexual use) adoption, Ward et al. (2016, 2018) defined it in a broader form as when women “self-objectify (p. 13; p. 31)”. Their adoption of APA’s sexualization to self-sexualization was rather replication of self-objectification and they perceived self-objectification as one component of self-sexualization. Accordingly, when they operationalize self-sexualization, they accessed individuals engaging in body monitoring (i.e., manifestation of self-objectification), using the surveillance scale of the objectified body consciousness scale (Lindberg et al. 2006). However, as it has been addressed in the previous section, there is a meaningful difference between the two concepts and its operationalization should reflect the difference accordingly; in other words, self-objectification is not adequate to access self-sexualization.

In this paper, we propose the first condition of self-sexualization as sexual subjectification, that is favoring sexual self-objectification. This condition is adopted from APA’s definition of self-sexualization (i.e., treating and experiencing oneself as a sexual object) with positive attitudes toward the self-sexualization as Gill (2008) and Attwood’s (2009) descriptions of sexual subjectification. A self-sexualizer who is in this condition not only seeks men’s attention but also does it to please herself—however, the pleasure may come from getting a man’s approval or from believing that her look or action would be appraised by men.

Sexual subjectification can be seen as an extension of the definition of self-sexualization provided by the APA. In sexual subjectification, a woman still treats herself as if she were a sexual object, yet the treatment is willingly chosen by the woman (Attwood 2009; Gill 2008). Favoring sexual objectification of oneself is different from the conceptualization where self-sexualization is limited to behavior (Allen 2013; Allen and Gervais 2012; Smolak et al. 2014). A self-sexualizer in this condition holds favorable attitudes towards self-sexual objectification. She believes that sexual subjectification is pleasurable, playful, liberating, and empowering.

Condition 2: Equating Physical Attractiveness with Being Sexy

The second condition is also adopted from the APA’s condition of sexualization (i.e., a person is held to a standard that equates physical attractiveness with being sexy) and adapted to oneself. This condition of self-sexualization is equating physical attractiveness with being sexy as one’s standard (e.g., How sexy I am is a measure of how physically attractive I am). In the same way, Hall et al. (2012) and Ward et al. (2016, 2018) adopted this condition in defining self-sexualization.

It is possible to manage appearance to be attractive in an aesthetically pleasing way by wearing proper attire for an occasion (e.g., beautify, charming, elegant, graceful, stylish). However, the self-sexualizers consistently direct their appearance management efforts to highlight their sexual appeal as the only way to appear attractive. Similar to this distinction, Smolak et al. (2014) described the differences between an attractive appearance and a sexual appearance. They suggested three characteristics of attractiveness: a well-groomed appearance (e.g., clean hair), within the boundary of social norms (e.g., average size body type), and looking “natural” (p. 2). On the other hand, they identified a sexy appearance as emphasizing sexualized body parts, such as breasts or buttocks. Self-sexualizers believe that being physically attractive is the same as being sexy and believe that they are not physically attractive unless they look sexy. As they equate physical attractiveness with being sexy, they need to look sexy to appear physically attractive.

Condition 3: Relating Sexual Desirability to Self-esteem

The third condition that we propose is relating one’s sexual desirability to self-esteem. This condition is adopted from one of four conditions of sexualization by APA (i.e., a person’s value comes only from his or her sexual appeal or behavior, to the exclusion of other characteristics) and adapted to oneself. Similarly, Hall et al. (2012) and Ward et al. (2016, 2018) adopted the APA’s sexualization condition in defining self-sexualization as assuming one’s value comes primarily from their sexual appeal, sexual appearance, or sexual behavior. (Hall’s study included sexual appeal and sexual behavior. Ward’s study included sexual appeal and sexual appearance.) Accordingly, Ward and her colleagues operationalized this condition by measuring the degree to which individuals base their self-worth on their sexual appeal that is focused on appearance, using the sexual appeal self-worth scale (Gordon and Ward 2000).

Rather than using terms like sexual appeal, sexual appearance, or sexual behavior, we propose using sexual desirability, which could include all efforts to be sexually desirable. This condition of self-sexualization refers to the influence of sexual desirably (either actually being sexual desired by others or believing that she is sexually desirable) to an individual’s thoughts about self (e.g., Being sexually desirable to others increases my self-esteem). In other words, a self-sexualizer who is in this condition relates her sexual desirability to her self-esteem to a greater degree than other women. McKenney and Bigler’s (2010) definition of internalized sexuality is in the same strain. In their study of developing a scale to measure internalized sexualization for pre- and early adolescent girls, they defined a concept of internalized sexualization as internalization of the belief that sexual attractiveness to males is an important aspect of identity.

A contingency of self-worth is comparable to this self-sexualization condition. A contingency of self-worth refers to the domain or domains on which a person’s self-esteem is based (Crocker and Wolfe 2001). A person must satisfy the domain in order to have high self-esteem. For example, if a persons’ contingency domain is in academics, then successes and failures in academic performance will determine how valuable the person perceives herself. Crocker and Wolfe (2001) identified seven domains of self-worth contingencies among college students. They are appearance, social approval, academic competency, success in competition with others, family support, virtue, and God’s love. A person can simultaneously hold several contingencies of self-worth and the relative importance of each may vary by contingency.

Similar to contingencies of self-worth, a self-sexualizer considers being sexually desirable as an important domain to be satisfied. To her, being sexually desirable is highly related to her self-esteem. She may also base her self-esteem on other contingencies besides beings sexually desirable, such as others’ approval, but her self-esteem is also dependent on sexual desirability.

Condition 4: Contextualizing Sexual Boundary

Unlike the three previous conditions, researchers have not attempted to include the fourth condition in defining self-sexualization. The fourth condition of sexualization (i.e., sexuality is inappropriately imposed upon a person) is particularly difficult to adopt to oneself, because of the term ‘inappropriateness.’ Inappropriateness refers to improper, unacceptable, unsuited or ill-suited, and incongruous (Collins thesaurus of the English language, n.d.). Inappropriate sexuality includes socially improper and/or morally unacceptable sexual beliefs and behaviors, such as sexual degradation, sexual aggression, verbal and physical sexual abuse. It also includes disinhibited sexual behaviors, such as prostitution, exposure of genitals, or masturbation in a public place (Queensland Health 2011). When the APA explained the inappropriate imposition of sexuality, they especially related it to children being imbued with adult sexuality. This type of sexualization is considered inappropriate because the sexuality violates social norms. It is considered as sexual abuse, exploitation of sexuality, and violation towards a person subject to protection. However, as the APA acknowledged, inappropriate sexuality can be imposed upon anyone.

The question arises: Can a person’s self-sexualization be inappropriate for herself? If she is doing it to herself, how can inappropriateness (or appropriateness) be played into one’s own action to oneself? It is possible that one’s sexual behavior may be considered appropriate to one person but the same sexual behavior may be considered inappropriate to another person, given that interpretations of “appropriate” sexuality can vary by individual. Thus, instead of the term inappropriate sexuality, specific words need to be used to explicitly describe this condition. In the process of adopting the APA’s fourth condition of sexualization to oneself, inappropriate sexuality is adapted to any type of sexual invasion or violation which includes sexual degradation, verbal and physical sexual aggression, and unwelcomed sexual attention and advances.

Invasions and violations of sexuality are improper and unacceptable sexual behavior. Where invasions or violations of sexuality are “excused, legitimized and viewed as inevitable”, (White and Smith, 2004, p. 174) the term rape culture is used. Rape culture refers to prevailing social attitudes that normalize, trivialize, and quietly condone male sexual assault and abuse against women (Wilhelm 2015). Considerable attention has been given to the rape culture itself as well as prevention of sexual assault (e.g., Sharp et al. 2017). For example, “It’s on Us” campaign was launched by Barack Obama in 2015 to increase awareness and fight sexual assault on college campuses.

While efforts in fighting against sexual violence toward women increase, there is some evidence of women accepting invasions of their own sexuality or other women’s sexuality. The popularity of Tucker Max, a young male blogger who posted his hook-up stories on his website, illustrates a type of sexual degradation acceptance. He has a large male and female fan base for his books and movies, even though his stories include leaving a sex partner naked on the street, calling a sexual partner a cum dumpster, and hiding a friend in his closet to videotape him having sex with a woman (Lynch 2012). Acceptance of such sexual degradation was made possible, even to women, because of the use of humor as a means to excuse his misogynic stories (Lynch 2012), just as the sexist jokes were accepted and enjoyed. Freud (1960) called this type of humor hostile humor because it insults a person, reveals flaws, and puts the person into destruction or suffering. Mutual participation in hostile humor entails joining in with the insulting of a target person. It provides a cathartic reduction of aggression for the target of the jokes while concealing the destructive motives of the instigator.

The fourth condition of self-sexualization that we propose deals with acceptance of sexual invasions (e.g., sexual aggression, uninvited sexual remarks, unwelcomed sexual attention, groping) in a particular situation (e.g., at parties, bars, clubs), in other words, contextualizing sexual boundaries. For example, some young female adults referred to “dirty, groping, grabbing” encounters with men as normal and commonplace when they went to some bars (Lynch 2007). Where sexual interactions, either physical or non-physical, are frequent, normalized, and somewhat expected (e.g., parties, bars, or clubs), a woman may compromise her sexual boundaries and accept invasion of her sexuality to a certain degree due to the context she is in, and it may depend on the degree of her sexual permissiveness. She may just go with the flow, put up with, or tolerate sexual invasions to some degree, hold beliefs belonging to the rape culture, or flirtatiously invite sexual teases. It is possible that a woman contextualizes her sexual boundary to fit with the context (e.g., flashing of breasts for crowd cheering) or she may learn to do so from peers who gained popularity from self-sexualization. She may also attempt to appear sexually adventurous, open, and available.

Self-sexualizers who tap into this condition may share similarities with individuals with a high tolerance for sexual harassment or accept the degradation of women through jokes. Women who tolerate sexual harassment are likely to accept rape myths and hold adversarial sexual beliefs that sexual relationships are fundamentally exploitative and manipulative (Reilly et al. 1992). Women who enjoy sexist jokes also are more likely to accept interpersonal violence and have adversarial sexual beliefs (Ryan and Kanjorski 1998). Research about women who intentionally and playfully accept invasions of their sexual boundaries need to be conducted. It is possible that these self-sexualizers are less offended by sexist jokes or stories (e.g., stories by Tucker Max) if the person lives a hyper-sexualized lifestyle (e.g., a fan of Tucker Max blogs, participates in the hook-up culture).

Conclusion

In a hyper-sexualized culture, pornographic imagery is chic and sexual appeals are highly valued. Women participating in this culture engage in multiple behaviors that are designed to enhance their sexual appeal and sexuality, from wearing clothes that draw attention to their sexual body parts to flashing their breasts in public. Participation in such a culture is reflected in their values, beliefs, attitudes, and life choices. Women may have been cultivated to self-sexualize by constant exposure to celebrities who replicate pornographic sexuality. Some positive feelings, such as a feeling of being in control or accepted, may also contribute to self-sexualization. Yet, we have rather limited knowledge of the phenomenon whereby women voluntarily impose sexualization upon themselves because researchers have not yet come to a consensus on a definition of self-sexualization nor clarified the concept.

As a preliminary work in clarifying the concept self-sexualization, conceptual murkiness was discussed among the terms: objectification, sexual objectification, sexualization, self-objectification, and self-sexualization. In doing so, the distinction of self-sexualization from other related concepts was recognized. In line with the previous researcher’s attempts in defining self-sexualization (APA 2007; Hall et al. 2012; Ward et al. 2016, 2018), we defined self-sexualization as the voluntary imposition of sexualization to the self, in accordance with Ward and her colleagues’ definition (2016, 2018). We proposed the full adoption of the four conditions of sexualization by APA to self-sexualization. Because the previous studies have not provided the description of each condition, we explicated each condition of self-sexualization. The four conditions of self-sexualization are: (1) favoring sexual self-objectification, that is sexual subjectification, (2) equating physical attractiveness with being sexy as one’s standard, (3) relating one’s sexual desirability to self-esteem, and (4) contextualizing sexual boundaries.

Because the current self-sexualizing phenomenon is mostly prevalent in women, the existing literature accordingly captured self-sexualization among women. We also have focused on female self-sexualization. Addressing female self-sexualization without exploring self-sexualization of other groups (e.g., male, homosexual, bisexual) may have limited its scope to a field where distinctive relation dynamics exist in heterosexual relationships, such as unequal power relations. This thesis began female self-sexualization with possibilities to expand to explore self-sexualization among other demographically and culturally diverse groups.

Another limitation to this study is the scope of self-sexualization. The four conditions were adapted from the four conditions of sexualization by APA (2007). The APA is the largest and leading scientific and professional organization of psychologists providing highly reliable information. However, exploration of other possible conditions of self-sexualization would ensure additional credible validity evidence based on the content.

Not all women experience the same degree of sexual objectification, nor do all men sexually objectify women. Although the views of self-sexualization vary along with the degree of involvement in self-sexualization, a growing number of women actively participate in the hyper-sexualized culture. By clarifying the concept of self-sexualization, we can arrive at a more comprehensive understanding of individuals who self-sexualize and the culture they live in.

References

Allen, J. M. (2013). The drive to be sexy: Belonging motivation and optimal distinctiveness in women’s self-sexualization (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nebraska). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/dissertations/AAI3559213/.

Allen, J. M., & Gervais, S. J. (2012). The drive to be sexy: Prejudice and core motivations in women’s self-sexualization. In N. S. Gotsiridze-Columbus (Ed.), Psychology of prejudice: Interdisciplinary perspectives on contemporary issues (pp. 77–112). New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

American Psychological Association, Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. (2007). Report of the APA task force on the sexualization of girls. Retrieved from www.apa.org/pi/wpo/sexualization.html.

Attwood, F. (2009). Mainstreaming sex: The sexualisation of western culture. New York, NY: IB Tauris.

Aubrey, J. S., Gamble, H., & Hahn, R. (2017). Empowered sexual objects? The priming influence of self-sexualization on thoughts and beliefs related to gender, sex, and power. Western Journal of Communication, 81(3), 362–384.

Bartky, S. L. (1990). Femininity and domination: Studies in the phenomenology of oppression. New York, NY: Routledge.

Blake, K. R., Bastian, B., & Denson, T. F. (2016). Perceptions of low agency and high sexual openness mediate the relationship between sexualization and sexual aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 42(5):483–497.

Braun, V. (2005). In search of (better) sexual pleasure: Female genital ‘cosmetic’ surgery. Sexualities, 8(4), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460705056625.

Calogero, R. M., Tantleff-Dunn, S. E., & Thompson, J. (2011). Self-objectification in women: Causes, consequences, and counteractions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Cash, T. F., & Kilcullen, R. N. (1985). The aye of the beholder: Susceptibility to sexism and beautyism in the evaluation of managerial applicants. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 15(4), 591–605.

Crocker, J., & Wolfe, C. T. (2001). Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review, 108(3), 593–623.

Davies, L. (2012). Sienna Miller nude: Expect the same ballyhoo as Demi Moore’s Vanity Fair appearance. The Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-features/9659350/Sienna-Miller-nude-expect-the-same-ballyhoo-as-Demi-Moores-Vanity-Fair-appearance.html.

Erchull, M. J., & Liss, M. (2013). Feminist who flaunt it: Exploring the enjoyment of sexualization among young feminist women. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(12), 2341–2349.

Erchull, M. J., & Liss, M. (2014). The object of one’s desire: How perceived sexual empowerment through objectification is related to sexual outcomes. Sexuality and Culture, 18(4), 773–788.

Fahs, B. (2009). Compulsory bisexuality?: The challenges of modern sexual fluidity. Journal of Bisexuality, 9(3–4), 431–449.

Fahs, B. (2014). Genital panics: Constructing the vagina in women’s qualitative narratives about pubic hair, menstrual sex, and vaginal self-image. Body Image, 11(3), 210–218.

Ferguson, C. J. (2011). Sexting behaviors among young Hispanic women: Incidence and association with other high-risk sexual behaviors. Psychiatric Quarterly, 82(3), 239–243.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory. Psychology of Women quarterly, 21(2), 173–206.

Freud, S. (1960). Jokes and their relation to the unconscious. New York, NY: Norton.

Gerbner, G. (1972). Communication and scial environment. Scientific American, 227(3), 152–162.

Gill, R. (2008). Empowerment/sexism: Figuring female sexual agency in contemporary advertising. Feminism and Psychology, 18(1), 35–60.

Goodman, M. P. (2011). Female genital cosmetic and plastic surgery: A review. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(6), 1813–1825. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02254.x.

Gordon, M. K., & Ward, L. M. (2000). I’m beautiful, therefore I’m worthy: Assessing associations between media use and adolescents’ self-worth. In: Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Chicago.

Hall, P. C., West, J. H., & McIntyre, E. (2012). Female self-sexualization in Myspace.com personal profile photographs. Sexuality and Culture, 16(1), 1–16.

Jeffreys, S. (2005). Beauty and misogyny: Harmful cultural practices in the West. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jhally, S., & Kilbourne, J. (2010). Killing us softly 4: Advertising’s image of women. Northampton, MA: Media Education Foundation.

Kammeyer, K. (2008). A hypersexual society: Sexual discourse, erotica, and pornography in America today. New York, NY: Plagrave Macmillan.

Klaassen, M. J., & Peter, J. (2015). Gender (in)equality in Internet pornography: A content analysis of popular pornographic Internet videos. The Journal of Sex Research, 52(7), 721–735.

Labre, M. P. (2002). Adolescent boys and the muscular male body ideal. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(4), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00413-X.

Landy, D., & Sigall, H. (1974). Beauty is talent: Task evaluation as a function of the performer’s physical attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29(3), 299.

Levy, A. (2006). Female chauvinist pigs: Women and the rise of raunch culture. New York, NY: Free Press.

Lindberg, S. M., Hyde, J. S., & McKinley, N. M. (2006). A measure of objectified body consciousness for preadolescent and adolescent youth. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(1), 65–76.

Liss, M., Erchull, M. J., & Ramsey, L. R. (2011). Empowering or oppressing? Development and exploration of the enjoyment of sexualization scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(1), 55–68.

Lynch, A. (2007). Expanding the definition of provocative dress: An examination of female flashing behavior on a college campus. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 25(2), 184–201.

Lynch, A. (2012). Porn chic: Exploring the contours of raunch eroticism. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

McKenney, S. J., & Bigler, R. S. (2010). Development of the internalized sexualization scale (ISS) for pre- and early adolescent girls. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Philadelphia, PA.

McNair, B. (2002). Striptease culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Moffitt, L. B., & Szymanski, D. M. (2011). Experiencing sexually objectifying environments: A qualitative study. The Counseling Psychologist, 39(1), 67–106.

Morris, D. (2004). New naked woman: A study of the female body. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books.

Nowatzki, J., & Morry, M. M. (2009). Women’s intentions regarding, and acceptance of, self-sexualizing behavior. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33(1), 95–107.

Nussbaum, M. C. (1995). Objectification. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 24(4), 249–291.

Ouytsel, J., Ponnet, K., Walrave, M., & d’Haenens, L. (2017a). Adolescent sexting from a social learning perspective. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 287–298.

Ouytsel, J., Van Gool, E., Walrave, M., Ponnet, K., & Peeters, E. (2017b). Sexting: adolescents’ perceptions of the applications used for, motives for, and consequences of sexting. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(4), 446–470.

Peterson, Z. D. (2010). What is sexual empowerment? A multidimensional and process-oriented approach to adolescent girls’ sexual empowerment. Sex Roles, 62(5–6), 307–313.

Philpott, A., Singh, A., & Gamlin, J. (2017). Blurring the boundaries of public health: It’s time to make safer sex porn and erotic sex education. IDS Bulletin-Institute of Development Studies, 48(1), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2017.108.

Queensland Health, Queensland Government. (2011). What are disinhibited and inappropriate sexual behaviours. Retrieved from http://www.health.qld.gov.au/abios/behaviour/family_sup_worker/disinhib_behav_fsw.pdf.

Ramsey, L. R., Marotta, J. A., & Hoyt, T. (2017). Sexualized, objectified, but not satisfied: Enjoying sexualization relates to lower relationship satisfaction through perceived partner-objectification. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34(2), 258–278.

Reilly, M. E., Lott, B., Caldwell, D., & DeLuca, L. (1992). Tolerance for sexual harassment related to self-reported sexual victimization. Gender and Society, 6(1), 122–138.

Ronai, C. R., & Ellis, C. (1989). Turn-ons for money: Interactional strategies of the table dancer. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 18(3), 271–298.

Ryan, K. M., & Kanjorski, J. (1998). The enjoyment of sexist humor, rape attitudes, and relationship aggression in college students. Sex Roles, 38(9–10), 743–756.

Sabina, C., Wolak, J., & Finkelhor, D. (2008). The nature and dynamics of Internet pornography exposure for youth. Cyber Psychology and Behavior, 11(6), 691–693.

Sarracino, C., & Scott, K. M. (2008). The porning of America: The rise of porn culture, what it means, and where we go from here. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Sharp, E. A., Weiser, D. A., Lavigne, D. E., & Kelly, R. C. (2017). From furious to fearless: Faculty action and feminist praxis in response to rape culture on college campuses. Family Relations, 66(1), 75–88.

Sigall, H., & Landy, D. (1973). Radiating beauty: Effects of having a physically attractive partner on person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28(2), 218–224.

Smolak, L., Murnen, S. K., & Myers, T. A. (2014). Sexualizing the self: What college women and men think about and do to be “Sexy”. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(3), 379–397.

Snyder, M., Tanke, E. D., & Berscheid, E. (1977). Social perception and interpersonal behavior: On the self-fulfilling nature of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(9), 656.

Trekels, J., Ward, L. M., & Eggermont, S. (2018). I “like” the way you look: How appearance-focused and overall Facebook use contribute to adolescents’ self-sexualization. Computers in Human Behavior, 81, 198–208.

Walster, E., Aronson, V., Abrahams, D., & Rottman, L. (1966). Importance of physical attractiveness in dating behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(5), 508–516.

Walter, N. (2011). Living dolls: The return of sexism. London: Virago Press.

Ward, L. M. (2016). Media and sexualization: State of empirical research, 1995–2015. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 560–577.

Ward, L. M., Seabrook, R. C., Grower, P., Giaccardi, S., & Lippman, J. R. (2018). Sexual object or sexual subject? Media use, self-sexualization, and sexual agency among undergraduate women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 42(1), 29–43.

Ward, L. M., Seabrook, R. C., Manago, A., & Reed, L. (2016). Contributions of diverse media to self-sexualization among undergraduate women and men. Sex Roles, 74(1–2), 12–23.

White, J. W., & Smith, P. H. (2004). A longitudinal perspective on physical and sexual intimate partner violence against women. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. (NCJ Publication No. 199708). Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/199708.pdf.

Whitehead, K., & Kurz, T. (2009). Empowerment and the pole: A discursive investigation of the reinvention of pole dancing as a recreational activity. Feminism and Psychology, 19(2), 224–244.

Wilhelm, H. (2015). The ‘rape culture’ lie zero shades of grey. Commentary. Retrieved from https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/therape-culture-lie/.

Yost, M. R., & McCarthy, L. (2012). Girls gone wild? Heterosexual women’s same-sex encounters at college parties. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36(1), 7–24.

Zurbriggen, E. L. (2013). Objectification, self-objectification, and societal change. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1(1), 188–215. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v1i1.94.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, D., DeLong, M. Defining Female Self Sexualization for the Twenty-First Century. Sexuality & Culture 23, 1350–1371 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09617-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09617-3