Abstract

This paper examines gender differences in the identity concerns of sexual minorities in China and the impact of individual and community-level socioeconomic statuses, familial, and cultural factors. A sample of 1076 non-heterosexual young adults (employed, aged 20–35) completed an online questionnaire on only child status, co-residence with parents, traditional values, familial pressure to marry, identity concerns, and demographic information. The findings show that gender impacts identity concerns. Men indicated a higher level of identity concern than women. Both traditional values and familial pressure to marry positively predict the level of identity concern for men and women. While co-residence with parents is a significant predictor for men, women are more affected by region of residence. The findings suggest that the identity concerns of men are mainly related to familial and cultural factors while women’s concerns are also influenced by community-related socioeconomic-status factors. This paper contributes to a better understanding of the role of gender in shaping the lives and experiences of sexual minority people in contemporary China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Essentialist paradigms emphasize a biological basis for sexual orientation and view sexual identity as natural and the inevitable realization of one’s innate disposition. Sexual identity formation is a linear process which moves from the early stages of identity confusion to the final stages of pride and identity integration (Cass 1979; Coleman 1982; Isaacs and McKendrick 1992). Social constructionist paradigms focus on the time and place contingencies of sexual identity, which show its historical and cultural fluidity (Eliason and Schope 2007; Seidman 2014). Questions have been raised regarding the global applicability of models that focus on being out-and-proud, a concept that can be allotted to the predominant Anglo-Saxon construction of homosexuality as a distinct sexual identity. These models emphasize the immutability of sexual identification and positive public identity during developmental maturity, and in doing so, neglect that managing a stigmatized identity can be a lifelong process that is never fully “resolved” (Kaufman and Johnson 2004).

Research has also explored how cultural and ethnic factors complicate sexual identity construction and expression. Related accounts provided by Anglo-Cypriot gay men show that many primarily construct their identity based on local family and community culture (Phellas 2005). Jewish sexual minorities rely on strategies which include compartmentalization of identities when faced with cultural, religious, and sexual identity conflicts (Coyle and Rafalin 2001; Faulkner and Hecht 2011). Chinese Confucian culture has long defined an individual primarily within the context of familial relationships. Since lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) identities are considered to impede family duties, sexual identity in contemporary China is fluid and fragmented. In fact, sexual identity oscillates from heterosexual to homosexual depending on the context (Li et al. 2010).

Mohr and Fassinger (2000) conceptualized sexual identity as a dynamic continuum composed of multiple dimensions rather than discrete stages of identity development. One or multiple dimensions of experience can be relevant for negotiating sexual identity and self-disclosure in a social environment. Since lesbians and gay men may face different types of stigmatization, exploring gender differences in sexual minority identification can provide a more nuanced understanding of the different experiences among sexual minorities. Of particular importance in this paper, Mohr and Fassinger (2000) found that compared to lesbians, gay men had higher levels of identity concerns, including internalized homonegativity and need for acceptance, which were attributed to the more rigid male role expectations and the heavier societal sanctions against male homosexuality. More generally, previous research found that an understanding of the level of identity concern is critical for understanding life experiences and health conditions of sexual minorities (Wright and Perry 2006), particularly in non-Western societies which feature more fluid conceptualizations of sexual identity (Koo et al. 2014; Li et al. 2010; Nguyen and Angelique 2017)

However, the study by Mohr and Fassinger (2000) was conducted in the US and the American cultural context. Herek (1986) stated that the male sex role in contemporary America explicitly emphasizes the importance of heterosexuality to masculinity. Many American men affirm their masculinity by rejecting those who violate the heterosexual norm. Therefore, their attitude toward gay men is particularly negative compared to women (Kite and Whitley 1996). By contrast, Chinese General Social Survey findings suggest there are no significant gender difference in attitudes towards homosexuality in China (Yeung and Hu 2016), indicating that the relationship between gender and attitudes toward homosexuality varies across societies and cultural contexts. The role of gender in shaping sexual minority identification in China has yet to be explored fully.

Few quantitative studies have explored the role of cultural factors on the attitudes of Chinese sexual minority women and men toward their sexual identities. Chow and Cheng (2010) showed that the use of shaming to culturally stigmatize same-sex orientation in parental socialization practices contributed to the internalized heterosexism of lesbians in Hong Kong and China. Hu and Wang (2013) found that Chinese LGB university students with stronger filial piety values, especially those who perceive that their parents have a traditional attitude toward marriage, have more negative attitudes toward the LGB identity. In addition, Hu et al. (2013) found that Chinese LGBs with higher acceptance concern were more likely to experience lower life satisfaction. Further, significant gender differences were discovered, with more men than women expressing heightened acceptance concerns and negative attitudes toward the LGB identity. Nguyen and Angelique (2017) echoed the gender difference in their study on the influence of Confucianism on Vietnamese sexual minorities, in that males had more internalized homonegativity.

These studies unfortunately examine gender primarily as a covariate. Warner and Shields (2013) cautioned against studying gender differences without investigating their underpinnings, thus facilitating gender stereotypes. Here, we highlight the importance of moving beyond treating gender as a socio-demographic variable to conceptualizing gender as a contextual factor worthy of examination in its own right. We argue further that cultural values and family duties are gendered and gender differences in sexual identity could be explained by contextual values in the family and society. We also assert that a study on sexual identity intersects with other identities, such as gender and social class, to shape sexual minority people’s life experiences (Warner and Shields 2013). Ours is the first attempt to examine how gender affects the sexual identity of Chinese LGBs and whether socioeconomic factors explain women’s and men’s experiences regarding sexual identity.

Explaining Sexual Identity and Gender Differences in China

Familial and Cultural Factors

Familial Pressure to Marry

In its transformation from a command to a market economy in 1978, China has enjoyed many modern developments. The Internet, in particular, has facilitated connection between sexual minorities in China and their global counterparts, thus creating a sense of belonging in a gay globality (Martin 2009). The development of the LGB culture in China also is cross-regional, influenced by the cultural flow in Hong Kong, Taiwan and China due to language and cultural proximities (Kam 2013). The term tongzhi (literally comrades), which first appeared in Hong Kong to describe LGBs, has been widely adopted as an identity label in China.

Market reform also has increased the visibility of sexual minorities and created space to negotiate sexual identity and cultural norms. Sun et al. (2006) showed that some men who have sex with men (MSM) who frequent gay venues adopt a collective identity as quannei, or being in the tongzhi circle. There also are men who call themselves “pure gay” or “pure tongzhi” who resist heterosexual marriage. A long-term exclusive homosexual partnership is becoming the ideal relationship model, albeit still far from common practice (Wei and Cai 2012). At the same time, there are those who adopt a heterosexual identity and marry as a social obligation, but enjoy same-sex encounters (Li et al. 2010).

Although a ‘sexual revolution’ has emerged in China (Farrer 2002; Zhang 2011), marriage remains the norm. The 2013 Chinese General Social Survey concluded that China stands alone in East Asia with near universal marriage. Almost all women marry by the age of 30, and men by 33, with median ages of 22 and 24 at marriage for rural women and men, and 24 and 25 for their urban counterparts respectively (Yeung and Hu 2016). Zhang and Chu (2005) estimated that 70–80 percent of urban male homosexuals/bisexuals and 90 percent of their rural peers are married or will marry a woman. Homosexual men used to hide in heterosexual marriage but the sexual revolution has made that more difficult (Wong 2014). Some gays and lesbians adopt marriages of convenience to conform to social expectations while carving out space for same-sex relationships (Engebretsen 2014; Kam 2013; Liu 2013).

Most Chinese sexual minority youth feel intense pressure to marry, particularly men, who bear the responsibility of continuing the family bloodline. The rights and responsibilities in traditional Chinese family relations have long been underpinned by the norms of patriarchy, patrilineality, and patrilocality. Inheritance rights and parental homes were reserved for sons (Zhang 2004). Sexual minority men’s gender-related privileges are balanced with a cost of intense pressure to marry and being subjected to frequent matchmaking. In sum, gender is critical for understanding the sexual minority identity concerns in China because men and women experience different types of marriage pressure.

Traditional Values

Feng et al. (2012) established a correlation between traditional Confucian values and negative views towards homosexuality in a study of Asian youths. This is particularly exacerbated in China with the revitalization of filial piety or xiao-shun, a core Confucian virtue, as a state remedy to solve the problem of caring for an aging population (Evans 2008; Wong 2014). Xiao-shun is a twofold concept (Hu and Scott 2016); grown children show xiao by reciprocating the care that they received from their parents. Shun is obeying, respecting and honoring parents by making them proud (Hu and Scott 2016). Remaining unmarried or living openly as gay is therefore considered unfilial. Hu and Wang (2013) found that LGBs who endorsed filial piety felt more pressured to marry with a more negative attitude toward the LGB identity.

Filial piety also extends to continuing the family line because Confucianism dictated that ‘Of the three most unfilial behaviors, having no descendent is the worst’. Women felt equal pressure as the men, as their position in the patrilineal family was only secured with male heirs. Even though the Chinese communist state advocated liberation for women by encouraging them to participate in the labor force, official discourses naturalized motherhood as a universality of womanhood. In post-reform China, childless women are considered to have unmeaningful and incomplete lives (Evans 2002).

The traditional cultural impacts on marriage, filial piety, reproduction and women’s values might influence the attitude of LGBs toward their sexual identity. Specifically, those with strong traditional values likely have more significant sexual identity concerns. We were also interested in determining any gender differences in attitude toward traditional values. Studies in Western countries found that women benefit more from social change and thus question traditional values (Esping-Andersen 2009). A qualitative study conducted in China revealed that some lesbian youths have begun to view marriage as an inherently oppressive institution, particularly for women, and look upon polyamory as an alternative (Cheng 2018) As such, we speculate that sexual minority females in China held less traditional values which help to understand the gender differences in concerns around sexual identity.

Only Child Status

The one-child policy in China was enacted in 1979 to limit population growth and was strictly enforced in urban areas (Zhang 2017). Growing concerns around an ageing population resulted in an end of the policy in October 2015, and married couples now can have two children. Several unintended consequences of the one-child policy have impacted family processes and dynamics. The hopes of parents fall on their one child regardless of gender. The only child could be especially filial as they bear full responsibility for the welfare, care and happiness of their parents (Bian et al. 1998; Deutsch 2006; Chen and Jordan 2018; Zhan 2004), and more compelled to fulfil social expectation to have children even if reluctant to do so (Chen and Jordan 2018).

Few quantitative studies have been done on the effects of China’s one-child policy on sexual minority identification. A qualitative study on Beijing LGBs found that having other siblings to fulfil the familial responsibilities facilitated more easily coming out and parental acceptance of same-sex orientation (Miles-Johnson and Wang 2018). Greenhalgh (2001) argued that urban female only children have benefitted from the policy, as they are encouraged by parents to resist gender norms (Deutsch 2006) and have more liberal ideas about gender (Davis and Sensenbrenner 2000; Fong 2002; Tsui and Rich 2002; Wu 1996). In light of such, we also suspect that being an only child is more likely to affect the identity concerns of sexual minority males than females.

Co-residence with Parents

Another cultural impact of the one-child policy is the erosion of patrilineal and patrilocal norms. Before the policy, parents preferred to co-reside with a son (Logan et al. 1998). A marital home was arranged for sons and unmarried daughters had to leave (Davis 1993). The one-child policy changed gender-specific expectations around familial duties, partly due to the absence of sons (Chen and Jordan 2018; Deutsch 2006). Urban families had to accept daughters as functionally equivalent to sons (Ikels 1993; Logan et al. 1998). Patrilocal co-residence with unmarried sons, while more frequent than with unmarried daughters (Zhang 2004), has been weakened by this policy. Consequently, we propose that gender differences exist in co-residence, and co-residence with parents is associated with negative attitudes toward sexual identity.

Individual and Community-Level Socioeconomic Statuses (SESs)

SES is a construct that captures the social position of an individual, including the power, prestige, resources, and material well-being that one enjoys (Conger et al. 2010; Oakes and Rossi 2003), typically assessed in quantitative research based on one’s education, income, and occupational status (Ensminger and Forthergill 2003). Health research has further emphasized community-level SES which is the availability and accessibility of service and personnel, infrastructure, communication and education, and other community factors (Conger et al. 2010; Zimmer et al. 2010). We extend this work and argue that SES also likely influences sexual minority identification at both the individual and community levels. Those with higher SESs have more resources to cope with discrimination and will likely develop a more positive identity with fewer sexual identity concerns. Also, LGBs live in different communities; some of the more developed communities may offer more resources and support.

While the three indicators of individual SES (education, income and occupational status) are positively correlated (Ensminger and Forthergill 2003), each can predict sexual minority identification differently. Education has a more consistent relationship with sexual identity, whereas this is not so for income and occupational status. A New Zealand study found that higher educated individuals were more satisfied with their LGB identity because the less educated tended to come out earlier which resulted in bullying incidents (Henrickson 2008). An inverse relationship between education and internalized homophobia was also found among American and South African gay and bisexual men (Herrick et al. 2013; Vu et al. 2012; Weber-Gilmore et al. 2011).

Badgett (1995) stated that the influence of income and occupational status is difficult to determine a priori. Workers with higher paying jobs might have the financial means to better manage social stigma, thus increasing their likelihood of disclosure. Yet they may have more to lose; for example, Schneider (1986) found that lesbians with supervisory roles were reluctant to disclose their sexual identity due to the cultural fear of homosexuals in power positions.

No quantitative evidence exists in China on the influence of SES on sexual minority identification, but qualitative studies suggest that SES is important. Sun et al. (2006) found that MSM with higher SES found it easier to disclose their sexual identity to families and friends. By contrast, those with few economic resources, such as migrants, were more reserved about doing so. Qian (2017) found that working class gay men who cruised a public park in China suffer a more heteronormative environment in comparison to the middle-class cruisers, and therefore most hid their sexuality, and were in heterosexual marriages. Given the familial attitudes in China that Chinese men tend to carry more family responsibilities, we explored whether educational attainment, income and occupational status are more strongly associated with sexual identity concern among men.

Hukou and Region of Residence

Hukou is the household registration system in China, which classifies people as having either rural or urban residence based on the place of origin of their parents. The government uses hukou to restrict free migration by tying social rights and benefits to one’s hukou status. Rural migrants who live in the cities without an urban hukou have none of the social rights of their urban counterparts, and it is very difficult to obtain an urban hukou. Hukou is therefore an indicator of social prestige: urban citizens are modern and civilized, whereas their rural counterparts are not (Lui 2016; Solinger 1999). The structural inequalities associated with hukou status also serve to organize the gay community, resulting in greater exclusion of rural gay men, some of whom make their living through sex work (Jones 2007).

Region of residence is also indicative of accessible networks and resources at the community level. Qualitative studies have documented the visibility of gay and lesbian communities in the mega cities of China with populations that exceed 10 million and high levels of socio-economic development. The density and mobility of the population permit anonymity and diversity. Physical and social spaces such as gay bars and saunas also facilitate a sense of belonging (Sun et al. 2006). Social network groups in Beijing not only encourage lesbian gatherings but also cultivate activism to promote social change (Engebretsen 2014). These are unfathomable in rural areas. Therefore, young rural migrants leave to realize their sexuality and escape from homophobia (Kong 2011).

Quantitative research has established the influence of geographical differences in attitudes toward gender roles and patrilineal beliefs even with education considered, thus demonstrating that the effects of urbanization and modernization associated with geographical regions operate independently of education (Hu and Scott 2016). Lin et al. (2016) found that modernization factors, such as intergroup contact and exposure to modern media were predictors of greater tolerance in attitudes, toward homosexuality. This study explores whether there are gender differences in the sexual identity concerns of sexual minorities and whether geographical differences impact their experiences.

The Present Study

Prior studies in China have been largely limited by their use of homogeneous, college student samples and insufficient attention to the roles of gender and SES. Here, we use a community sample of 1076 young LGB adults (employed, 20–35 years old), to explore gender differences in their experiences and the extent that SES, familial and cultural factors explain for gender differences. We ask: (1) are there gender differences in sexual identity concerns? (2) Do occupation, annual income, education, hukou, region of residence, only child status, co-residence with parents, familial pressure to marry, and traditional values explain for such gender differences? (3) What are the most important predictors of identity concern among the nine hypothesized predictor variables among men and women?

Methods

Participants

The present study was conducted online via a Chinese survey website (wenjuan.com) between 2015 and 2017. Partner organizations (see Acknowledgement) helped distribute the online survey through their WeChat (a widely used social media platform in China) official platforms, group chats and other channels. The final sample of 1075 included 575 men (53.4%) and 501 women (46.6%) who identify themselves as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, with a mean age of 27.28 (SD = 5.15) and ranging from 20 to 35 years-old.

Measures and Procedure

The online survey included questions about socioeconomic status, family relations, marital status and relationship goals, and attitudes on traditional values and sexual identity. In this study, we examine the influence of gender on sexual identity and whether socioeconomic status, familial and cultural factors explain such gender differences. Gender in this paper refers to the gender assigned at birth. Participants provided information about their socio-economic standing, including region of residence, hukou status, education, annual income, and occupation.

Sexual Identity Concern

In this study Sexual Identity Concern was measured using 10 items from the Need for Acceptance and Identity Dissatisfaction subscales developed by Mohr and Fassinger (2000) and Mohr and Kendra (2011). Mohr and Fassinger’s (2000) model conceptualizes sexual minority identity as the multidimensional reaction toward one’s sexual orientation. While the Internalized Homonegativity subscale has received the most attention from scholars (Shidlo 1994; Berg et al. 2016; Meyer 1995); Herek (2004) cautions against the use of a clinical language that pathologizes particular identities and attitudes. Thus, we follow de Oliveira et al. (2012) and rename this scale Identity Dissatisfaction to focus attention on the degree to which an individual evaluates his/her sexual identity or orientation in a negative way.

The other critical dimension of sexual minority identity that we examine is the Need for Acceptance. According to Kendra and Mohr’s model (2011), Need for Acceptance measures the degree to which individuals are sensitive to the negative judgment of others about their sexual orientation, and it has been found to be associated with Identity Dissatisfaction.

We adopted the translated version of these two subscales from Lin’s (2013) study of gay bear subculture in China. Lin’s Chinese versions of subscales were tested with Principal Component Analysis and Reliability before they were finalized. Cronbach’s alphas of Need for Acceptance and Identity Dissatisfaction were .63 and .84 respectively in Lin’s (2013) study while the Cronbach’s alphas were .85 and .76 respectively for our sample.

There are five items in each subscale. All 10 items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Two items were scored reversely prior to summing. We computed a total composite score, Identity Concern, based on the respondents’ answers to the 10 questions. If respondents reported higher Identity Concern scores, it means that they have more concerns about their sexual identity status.

Traditional Values

We created a scale of Traditional Values based on four commonly heard sayings in Chinese society. These four items assess participants’ attitudes on about marriage, child-bearing, filial piety and women’s value (see Table 1). In Traditional Values, respondents were asked to rate their agreement or disagreement with statements (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Responses were averaged so that higher scores indicate stronger endorsement of traditional values. The Cronbach’s alpha for this unitary scale was .91 (principal components factor loadings are provided in Table 1).

Familial Pressure to Marry

Familial Pressure to Marry was assessed using three items. Respondents were asked “How often do your parents ask you to attend arranged blind dates”; “How often are you being urged to get married”; and, “How do you evaluate your overall marriage pressure from family”. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never or barely) to 5 (Very or always). The final score is a simple sum of the three items (range 3–15), with higher scores indicating feeling more family marriage pressure.

SES and Other Predictors

Individual and community SES was measured by the variables of education, annual income, occupation, hukou, and region of residence. We coded the educational levels into four levels: “secondary school and below”, “high diploma”, “university and above” and “post-graduate”. Occupation was grouped into four levels based on their social prestige (Li 2005) while students and people without earning jobs were excluded: “elementary and service workers”, “clerical workers and technicians”, “associate professionals” and “professionals and government officials”. Hukou status was coded as dummy variable to indicate “rural” or “urban” registration. Region of residence was coded into three categories: “county or below”, “Prefecture-level city” and “Provincial capitals and municipalities”. For annual income, we excluded numbers that were smaller than 1000 and conducted natural logarithmic transformation to normalize and facilitate data analysis. Only child status and co-residence with family are coded into dummy variables indicating “yes = 1” and “no = 0”.

All analyses were conducted using the sample of 1076 respondents. First, descriptive statistics by gender were calculated and evaluated for differences using a Chi-square test or a t test. In addition, a three-step hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to assess the individual and combined effects of the theorized predictors of Identity Concern. Gender was entered in step one. Socioeconomic status was assessed by the respondents’ education, annual income, occupation, hukou, and region of residence, and all of these variables were entered in step two. Familial and cultural factors, including only child status, co-residence with parents, traditional values, and familial pressure to marry were entered in step three. Lastly, separate regression models were estimated for males and females to determine whether socioeconomic status, familial, and/or cultural factors have different effects on males and females’ identity concern. For each gender, four models were estimated with three groups of predictors analyzed separately first and then jointly in the last model.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

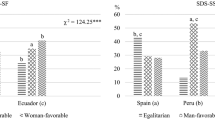

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the focal variables by gender. The data show that there is a gender difference in most of the variables examined (p < 0.01). The majority of our respondents were only children, with 58.3% of male and 61.3% of female. More male respondents (53.2%) than female respondents were living with their parents. More than half of our respondents indicated a high level of education, with 50.5% of male and 56.7% of female attained university education or above. The overall educational attainment among male respondents was lower than female respondents, with more than one-third of them (36.4%) indicating that they did not have a university degree. More male respondents (38.7%) than female respondents (20.5%) engaged in elementary and service occupation. On the other hand, female respondents were concentrated in clerical jobs. A majority of our respondents (male = 86.6%, female = 92.4%) lived in prefecture-level or above cities. More female respondents (76.4%) than male respondents (58.5%) lived in the most developed regions of provincial capitals or mega cities. Gender difference is shown in hukou too; 84.6% of female respondents held an urban hukou while 64.2% of male respondents held an urban hukou. Female respondents earned more than 80,000 RMB annually, while male respondents earned less than 70,000 RMB annually.

We also compared the mean scores of traditional values, familial pressure to marry and identity concern among our female and male respondents. Male respondents had higher scores than female respondents in traditional values and identity concern; no gender difference was observed in familial pressure to marry. The mean score for traditional values was 2.27 (p < 0.01); the mean score of this factor among male respondents was 2.70 while it was 1.78 among female respondents. The mean score for identity concern was 2.60 (p < 0.01); male respondents had higher score (2.96) in this factor than their female counterparts (2.20).

Regression Analysis

Gender Differences in Sexual Identity Concern

Table 3 presents the results from hierarchical regression analysis of sexual identity concern on gender, SES, familial and cultural factors. The gender difference in identity concern was significant at p < .001 (Model 1). The effect of gender on identity concern decreased to beta = − .36 when the SES factors were added to Model 2. Among the five predictor variables of SES, both annual income and region of residence significantly predicted identity concern negatively, indicating that participants who earned higher annual incomes and those who lived in developed regions with more resources and networks had lower identity concern (Model 2).

When familial and cultural factors were added in Model 3, the effects of annual income and region of residence on identity concern were no longer significant. The effect of gender on identity concern decreased to beta = -.19. The traditional values (beta = .54) and familial pressure to marry (beta = .17) positively predicted identity concern after controlling gender and socioeconomic status. In sum, after entry of all 10 predictors at model 3, the total variance in identity concern explained by the model as a whole was 50%, F (10, 636) = 65.73, p < .001. Cohen (1988) gave estimates of values of R2 of .02, .13, and .26 as corresponding to small, medium, and large effect sizes respectively. Based on Cohen’s guidelines, the R2 = .50 considers well above large effect size, indicating that these predictors have very strong influence on identity concern. In the final model, only three predictors were statistically significant, with traditional values (β = .54, p < .001) and the pressure to marry (β = .17, p < .001) having significantly positive effects on identity concerns only modestly reducing the magnitude of the gender difference (β = − 19, p < .001) compared with Models 1 and 2.

Gender Differences in the Predictors of Sexual Identity Concern

Results from separate analyses of the predictors of Identity Concern for males and females are reported in Table 4. For males, the total variance in their identity concern explained by all nine predictors as a whole was 49%, F (9, 382) = 41.90, p < .001. Cohen (1988) gave estimates of values of R2 of .02, .13, and .26 as corresponding to small, medium, and large effect sizes respectively. Based on Cohen’s guidelines, the R2 = .49 considers a very large effect size, indicating these predictors had strong influence on males’ identity concern. In the final model, three out of nine predictors were statistically significant, with traditional values recoding a highest beta value (β = .59, p < .001) and followed by familial pressure to marry (β = .20, p < .001) and co-residence with parents (β = .10, p < .05) as second and third high predictors.

As for females, the total variance in their identity concern explained by all nine predictors as a whole was 22%, F (9, 245) = 8.78, p < .001. Based on Cohen’s guidelines, the R2 = .22 considers a medium effect size, indicating that these predictors have fair influence on females’ identity concern. In the final model, three out of nine predictors were statistically significant, with traditional values recoding a highest beta value (β = .41, p < .001) and followed by familial pressure to marry (β = .17, p < .01) and region of residence (β = − .13, p < .05) as second and third high predictors.

In sum, traditional values and familial pressure to marry positively predicted males and females’ identity concern. In addition, co-residence with parents significantly predicted males’ identity concern while region of residence affected females’ identity concern.

Discussion

We primarily found that sexual minority males and females in China experience different levels of identity concern, with men having generally higher levels of identity dissatisfaction and greater need for acceptance than women. This echoes findings from prior studies in other parts of the world. While previous research attributed the American gay men’s negative attitudes toward sexual identity to the more rigid male role expectation and the heavier societal sanction against male homosexuality (Herek 1986; Mohr and Fassinger 2000), we found that culturally-specific factors in China have more impact. Most important, gender differences in sexual identity concern in China cannot be understood without taking into consideration familial and cultural factors associated with the Confucian cultural legacy.

Previous work has already validated the influence of cultural values on sexual minority identity in China. Apart from a more careful investigation of the familial and cultural factors on identity construction, the novelty of this study lies in its attempt to simultaneously examine the effect of socioeconomic status at the individual and community levels. While we found that higher income earners and urbanites tended to have lower levels of identity concern, the effects of individual and community SESs disappeared when analyzed alongside familial and cultural attitudes.

For both sexual minority males and females, traditional values (on marriage, reproduction, filial piety, and women’s values) was the best predictor of identity concern, followed by familial pressure to marry. Traditional values and practices do not simply disappear with modernity, but are instead redefined to cope with the pressures of modern life (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 2002). For instance, there is a renewed state emphasis on filial piety to address the caring needs of an aging population (Evans 2008). The Chinese government also maintains control over out-of-wedlock childbirth through implementation of strict and comprehensive family planning and hukou policies. Marriage remains the only legitimate institution through which to have children (Yeung and Hu 2016). Nevertheless, Chinese sexual minorities do not simply observe traditional values to comply with the state. Emotional attachment characterizes contemporary intergenerational relationships, so that children avoid antagonizing their parents, and find it difficult to dismiss familial pressure to marry (Evans 2008; Wong 2014). Our findings echo the findings of many qualitative studies on how sexual minorities in China negotiate traditional culture and the marriage imperative (Cheng 2018; Li et al. 2010; Miles-Johnson and Wang 2018).

Gender differences were observed in the predictors of identity concern. Co-residence with parents was the third most important predictor of identity concern for men, and region of residence for women. Chinese tradition deems that sons have a more important role in co-residence with and caring for parents, which stands in stark contrast with the Western culture in which daughters provide more care and support for parents (Raley and Bianchi 2006). Research has reported that Chinese adult sons are more likely than daughters to co-reside with their parents (Zhang 2004; Zhang et al. 2014). Sons’ co-residence with parents might be explained by the housing strategies of families, in which parents try hard to arrange a marital home for sons (Davis 1993). Co-resident children were found to have slightly higher level of filial piety compared with their non-coresident counterparts (Zhang et al. 2014). Sexual minority males who lived with their parents felt more obliged to meet parental expectations, thus expressing a higher level of identity concern than their female counterparts.

Women who lived in metropolises or provincial capitals tended to have lower levels of identity concern. Despite fewer commercial outlets for lesbians in the cities compared to gay men, activities by non-governmental organizations or social groups often frequently target lesbians. Salon gatherings were a safe space for discussions (Engebretsen 2014), and oral history projects fostered a sense of community in large urban cities (Kam 2013). A new form of lesbian kinship–the lesbian household–emerged in Shanghai whereby several lesbian friends and partners lived together to offer each other support (Kam 2013) Apart from these support groups and resources that help lesbians cope with identity stress, ideas of feminism and sexual rights were transmitted through inter-regional and transnational networks from queer communities in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and overseas. These all contributed to increasing the awareness of gender inequalities and a more positive evaluation of sexual identity.

A compelling finding was that sexual minority females were more likely than males to resist traditional values even though no significant gender differences were found in familial pressure to marry. Note that the traditional patriarchal, patrilineal and patrilocal norms that underpin family and marriage provided men with privilege and social power, but not women. Women had less power than their brother(s) before marriage, and perceived as outsiders by her husband’s family after marriage. This precarious position made it easier for lesbians to renounce marriage and traditional values (Rofel 2007; Chou 2001). Queer feminist activists have also campaigned against the ideological discourses that reinstate “Chinese tradition”, “femininity”, and “natural difference” (Liu et al. 2015). Consequently, more lesbians have disengaged from the traditional gendered roles including those of marriage.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Our study has some limitations. The non-random sample means that the findings may not be representative of the LGB population in China. Our respondents were mainly recruited through LGB organizations which helped to distribute the online survey through their own channels. Many of the participants are highly educated urbanites in mega cities like Beijing. Second, their SES might not accurately reflect the gender equality gaps that favor men in the larger society, with an over-representation of highly educated, high income female urbanites because we recruited women from online and social groups that work for gender equality. We also recruited male participants through organizations which provide HIV/STI services to people of diverse socio-economic backgrounds. Third, we created or modified the central measures of identity concern, traditional values, and familial pressure to marry. In our desire to conduct a short questionnaire with a high response rate, we did not use the complete LGB identity scale in Mohr and Kendra (2011), which would allow for examination of other dimensions such as concealment motivation and identity centrality.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the existing literature on gender and sexuality by offering a nuanced understanding of sexual minority identification in China. The results identify important predictors for level of identity concern. In particular, the large effect sizes underscore the importance of the predictors for males, namely traditional values, familial pressure to marry, and co-residence. Future studies could further explore the influence of other traditional values including the importance of patriarchal, patrilineal and patrilocal norms and underscore that future research should examine the extent that sexism and traditional gender role beliefs influence identity concern.

Conclusion

In this paper, we emphasize the importance of historical and cultural forces that shape the identity concerns of sexual minority women and men. In post-reform China where state discourses have revived Confucian family values, the sexual identity of LGBs should not be understood apart from the meaning of being a son or daughter. Since cultural values and family duties are gendered, gender cannot be simply regarded as a socio-demographic variable but conceptualized as a contextual factor in its own right.

We showed that sexual minority females were more likely than males to embrace their identity and resist traditional values. Apart from the familial and cultural factors, women’s identity concern was best explained by community SES. Large urban cities are influenced by the globalization of sexual identities and proliferation of lesbian and feminist groups, and offer a more conducive environment to explore and experience sexual identity. Therefore, gender differences in sexual identity not only offer a nuanced account of within group variability, but also show how tradition and modernity could influence the identity concerns of sexual minority males and females in different ways.

References

Badgett, M. V. L. (1995). The wage effects of sexual orientation discrimination. ILR Review, 48, 726–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979399504800408.

Beck, U., & Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2002). Individualization : Institutionalized individualism and its social and political consequences. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446218693.

Berg, R. C., Munthe-Kaas, H. M., & Ross, M. W. (2016). Internalized homonegativity: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. Journal of Homosexuality, 63, 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1083788.

Bian, F., Logan, J. R., & Bian, Y. (1998). Intergenerational relations in urban China: Proximity, contact, and help to parents. Demography, 35, 115–124. https://doi.org/10.2307/3004031.

Cass, V. C. (1979). Homosexuality identity formation. Journal of Homosexuality, 4, 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v04n03_01.

Chen, J., & Jordan, L. P. (2018). Intergenerational support in one- and multi-child families in China: Does child gender still matter? Research on Aging, 40, 180–204.

Cheng, F. K. (2018). Dilemmas of Chinese lesbian youths in contemporary mainland China. Sexuality and Culture, 22, 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-017-9460-8.

Chou, W. (2001). Homosexuality and the cultural politics of Tongzhi in Chinese societies. Journal of Homosexuality, 40, 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v40n03_03.

Chow, P. K. Y., & Cheng, S. T. (2010). Shame, internalized heterosexism, lesbian identity, and coming out to others: A comparative study of lesbians in mainland China and Hong Kong. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017930.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Coleman, E. (1982). Developmental stages of the coming-out process. American Behavioral Scientist, 25, 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276482025004009.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x.

Coyle, A., & Rafalin, D. (2001). Jewish gay men’s accounts of negotiating cultural, religious, and sexual identity. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 12, 21–48. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v12n04_02.

Davis, D. (1993). Urban households: supplicants to a socialist state. In Chinese families in the post-Mao era (pp. 51–77), Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Davis, D. S., & Sensenbrenner, J. S. (2000). Commercializing childhood: Parental purchases for Shanghai’s only child. In The consumer revolution in urban China (pp. 54–79). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

de Oliveira, J. M., Lopes, D., Costa, C. G., & Nogueira, C. (2012). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity scale (LGBIS): Construct validation, sensitivity analyses and other psychometric properties. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15, 334–347. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n1.37340.

Deutsch, F. M. (2006). Filial piety, patrilineality, and China’s one-child policy. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 366–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05283097.

Eliason, M. J., & Schope, R. (2007). Shifting sands or solid foundation? Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity formation. In I. H. Meyer & M. E. Northridge (Eds.), The health of sexual minorities. Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-31334-4.

Engebretsen, E. (2014). Queer women in urban China. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203085561.

Ensminger, M. E., & Forthergill, K. E. (2003). A decade of measuring SES: What it tells us and where to go from here. In M. H. Bornstein & R. H. Bradley (Eds.), Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development (pp. 13–27). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2009). The incomplete revolution: Adapting to women’s new roles. Cambridge: Polity.

Evans, H. (2002). Past, perfect or imperfect: Changing images of the ideal wife. In S. Brownell & J. N. Wasserstrom (Eds.), Chinese femiminities/Chinese masculinities: A reader, 335–360. New York: University of California Press.

Evans, H. (2008). The subject of gender : Daughters and mothers in urban China. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Farrer, J. C. (2002). Opening up : Youth sex culture and market reform in Shanghai. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Faulkner, S. L., & Hecht, M. L. (2011). The negotiation of closetable identities: A narrative analysis of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered queer jewish identity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28, 829–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407510391338.

Feng, Y., Lou, C., Gao, E., Tu, X., Cheng, Y., Emerson, M. R., et al. (2012). Adolescents’ and young adults’ perception of homosexuality and related factors in three Asian cities. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 50, S52–S60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.008.

Fong, V. L. (2002). China’s one-child policy and the empowerment of urban daughters. American Anthropologist, 104, 1098–1109. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2002.104.4.1098.

Greenhalgh, S. (2001). Fresh winds in Beijing: Chinese feminists speak out on the one-child policy and women’s lives. Signs, 26, 847–886. https://doi.org/10.1086/495630.

Henrickson, M. (2008). Deferring identity and social role in lesbian, gay and bisexual New Zealanders. Social Work Education, 27, 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470701709626.

Herek, G. M. (1986). On heterosexual masculinity. American Behavioral Scientist, 29, 563–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276486029005005.

Herek, G. M. (2004). Beyond “Homophobia”: Thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: A Journal of the NSRC, 1, 6–24. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2004.1.2.6.

Herrick, A. L., Stall, R., Chmiel, J. S., Guadamuz, T. E., Penniman, T., Shoptaw, S., et al. (2013). It gets better: Resolution of internalized homophobia over time and associations with positive health outcomes among MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 1423–1430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0392-x.

Hu, Y., & Scott, J. (2016). Family and gender values in China: Generational, geographic, and gender differences. Journal of Family Issues, 37, 1267–1293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14528710.

Hu, X., & Wang, Y. (2013). LGB identity among young Chinese: The influence of traditional culture. Journal of Homosexuality, 60, 667–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.773815.

Hu, X., Wang, Y., & Wu, C. Huei. (2013). Acceptance concern and life satisfaction for Chinese LGBs: The mediating role of self-concealment. Social Indicators Research, 114, 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0168-8.

Ikels, C. (1993). Settling accounts: The intergenerational contract in an age of reform. In D. Davis & S. Harrell (Eds.), Chinese families in the post-Mao era (pp. 307–334). Berkeley: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520077973.003.0012.

Isaacs, G., & McKendrick, B. (1992). Male homosexuality in South Africa: Identity formation, culture, and crisis. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

Jones, R. H. (2007). Imagined comrades and imaginary protections: Identity, community and sexual risk among men who have sex with men in China. Journal of Homosexuality, 53, 83–115. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v53n03_06.

Kam, L. Y. L. (2013). Shanghai lalas: Female tongzhi communities and politics in urban China. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. https://doi.org/10.5790/hongkong/9789888139453.001.0001.

Kaufman, J. M., & Johnson, C. (2004). Stigmatized individuals and the process of identity. Sociological Quarterly, 45, 807–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2004.tb02315.x.

Kite, M. E., & Whitley, B. E. (1996). Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual persons, behaviors, and civil rights: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296224002.

Kong, T. S. K. (2011). Chinese male homosexualities: Memba, Tongzhi and Golden Boy. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203849200.

Koo, F. K., Chow, E. P. F., Gao, L., Fu, X., Jing, J., Chen, L., & Zhang, L. (2014). Socio-cultural influences on the transmission of HIV among gay men in rural China. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 16, 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2014.883643.

Li, C. (2005). Prestige stratification in the contemporary China: Occupational prestige measures and socio-economic index (in Chinese). Sociological Studies, 2, 74–102.

Li, H., Holroyd, E., & Lau, J. T. F. (2010). Negotiating homosexual identities: The experiences of men who have sex with men in Guangzhou. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 12, 401–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050903551721.

Lin, C. (2013). Definition and cause of gay bear in Chinese homosexual subculture. Master’s thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai.

Lin, K., Button, D. M., Su, M., & Chen, S. (2016). Chinese college students’ attitudes toward homosexuality: Exploring the effects of traditional culture and modernizing factors. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13, 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-016-0223-3.

Liu, M. (2013). Two gay men seeking two lesbians: An analysis of Xinghun (formality marriage) ads on China’s Tianya.cn. Sexuality and Culture, 17, 494–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-012-9164-z.

Liu, W., Huang, A., & Ma, J. (2015). II. Young activists, new movements: Contemporary Chinese queer feminism and transnational genealogies. Feminism and Psychology, 25, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353514563091.

Logan, J. R., Bian, F., & Bian, Y. (1998). Tradition and change in the urban Chinese family: The case of living arrangements. Social Forces, 76, 851–882. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/76.3.851.

Lui, L. (2016). Gender, rural–urban inequality, and intermarriage in China. Social Forces, 95, 639–662. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sow076.

Martin, F. (2009). That global feeling: Sexual subjectivities and imagined geographies in Chinese-language lesbian cyberspaces. In G. Goggin & M. J. McLelland (Eds.), Internationalizing internet studies: Beyond anglophone paradigms. New York: Routledge.

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 38–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137286.

Miles-Johnson, T., & Wang, Y. (2018). ‘Hidden identities’: Perceptions of sexual identity in Beijing. British Journal of Sociology, 69, 323–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12279.

Mohr, J. J., & Fassinger, R. E. (2000). Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 33, 66–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-011-9194-5.

Mohr, J. J., & Kendra, M. S. (2011). Revision and extension of a multidimensional measure of sexual minority identity: The lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022858.

Nguyen, T., & Angelique, H. (2017). Internalized homonegativity, confucianism, and self-esteem at the emergence of an LGBTQ identity in modern Vietnam. Journal of Homosexuality, 64, 1617–1631. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1345231.

Oakes, J. M., & Rossi, P. H. (2003). The measurement of SES in health research: Current practice and steps toward a new approach. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 769–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00073-4.

Phellas, C. N. (2005). Cypriot gay men’s accounts of negotiating cultural and sexual identity: A qualitative study. Qualitative Sociology Review, 1, 65–83.

Qian, J. (2017). Beyond heteronormativity? Gay cruising, closeted experiences and self-disciplining subject in People’s Park, Guangzhou. Urban Geography, 38, 771–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1139408.

Raley, S., & Bianchi, S. (2006). Sons, daughters, and family processes: Does gender of children matter? Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 401–421. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.32.061604.123106.

Rofel, L. (2007). In J. Halberstam, & L. Lowe (Eds.), Desiring China: Experiments in neoliberalism, sexuality, and public culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Schneider, B. E. (1986). Coming out at work: Bridging the private/public gap. Work and Occupations, 13, 463–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888486013004002.

Seidman, S. (2014). The social construction of sexuality (3rd ed.). New York: Norton.

Shidlo, A. (1994). Internalized homophobia: conceptual and empirical issues in measurement. In B. Greene & G. M. Herek (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay issues. Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research, and clinical applications (Vol. 1, pp. 176–205). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483326757.n10.

Solinger, D. (1999). Constesing citizenship in urban China: Peasant migrants, the state, and the logic of the market. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Sun, Z., Farrer, J., & Choi, K. (2006). Sexual identity among men who have sex with men in Shanghai. China Perspectives, 64, 1–17.

Tsui, M., & Rich, L. (2002). The only child and educational opportunity for girls in urban China. Gender and Society, 16, 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243202016001005.

Vu, L., Tun, W., Sheehy, M., & Nel, D. (2012). Levels and correlates of internalized homophobia among men who have sex with men in Pretoria, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 16, 717–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-9948-4.

Warner, L. R., & Shields, S. A. (2013). The intersections of sexuality, gender, and race: Identity research at the crossroads. Sex Roles, 68, 803–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0281-4.

Weber-Gilmore, G., Roase, S., & Rubinstein, R. (2011). The impact of internalized homophobia on outness for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. The Professional Counselor, 1, 163–175. https://doi.org/10.15241/gwv.1.3.163.

Wei, W., & Cai, S. (2012). Exploring a new relationship model and lifestyle: A study of the partnership and family practice among gay couples in Chengdu. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 32, 57–85.

Wong, D. (2014). Asexuality in China’s sexual revolution: Asexual marriage as coping strategy. Sexualities, 18, 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460714544812.

Wright, E. R., & Perry, B. L. (2006). Sexual identity distress, social support, and the health of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Journal of Homosexuality, 51, 81–110. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n01_05.

Wu, D. Y. H. (1996). Chinese childhood socialization. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), Oxford handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 143–154). New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199541850.001.0001.

Yeung, W.-J. J., & Hu, S. (2016). Paradox in marriage values and behavior in contemporary China. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 2, 447–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X16659019.

Zhan, H. J. (2004). Willingness and expectations. Marriage & Family Review, 36, 175–200. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v36n01_08.

Zhang, Q. F. (2004). Economic transition and new patterns of parent-adult child coresidence in urban China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1231–1245. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1032062.

Zhang, B. (2011). The cultural politics of gender performance. Cultural Studies, 25, 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2010.483803.

Zhang, J. (2017). The evolution of China’s one-child policy and its effects on family outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31, 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.1.141.

Zhang, B. C., & Chu, Q. S. (2005). MSM and HIV/AIDS in China. Cell Research, 15, 858–864. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cr.7290359.

Zhang, Z., Gu, D., & Luo, Y. (2014). Coresidence With elderly parents in contemporary China: The role of filial piety, reciprocity, socioeconomic resources, and parental needs. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 29, 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-014-9239-4.

Zimmer, Z., Wen, M., & Kaneda, T. (2010). A multi-level analysis of urban/rural and socioeconomic differences in functional health status transition among older Chinese. Social Science and Medicine, 71, 559–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.048.

Acknowledgements

The research project was supported by the General Research Grant of the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. We are indebted to all our partner organizations China Lala Alliance, Zhitong Guangzhou LGBT Center, Straight-Gay Alliance, Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays China, and Midnight Blue Shenzhen for their endeavors to help distribute the online survey and recruit in-depth interview participants for this research project. We sincerely thank the volunteers Dian Dian, Xu Yuan, Wang Yiran, Hope and Wei Yuan for their participation in the early phase of the research project.

Funding

This study was funded by General Research Grant awarded by Research Grants Council, Hong Kong (Grant Number: 12605615).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. In addition, this study was granted with ethical approval from the Committee on the Use of Human and Animal Subjects in Teaching and Research, Hong Kong Baptist University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, D., Zhang, W., Kwan, Y.W. et al. Gender Differences in Identity Concerns Among Sexual Minority Young Adults in China: Socioeconomic Status, Familial, and Cultural Factors. Sexuality & Culture 23, 1167–1187 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09607-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09607-5