Abstract

Some researchers suggest that the observed boom in the levels of violence in Mexico since 2008 are a consequence of placing federal military forces in states with a significant organized crime presence. However, little has been said about the role of the changeable, competitive, and violent nature of criminal organizations on this increasing violence. Using the literature on inter- and intra-state conflicts as matter of analogy to explain organized crime developments in Mexico, fragmentation and cooperation seem to be determinant forces that alter the equilibrium within Mexican criminal groups, affecting their territorial control. By using a private dataset gathered by the Drug Policy Program at the Center for Economic Research and Teaching (CIDE), we examine the evolution of criminal organizations in Mexico by focusing on their different alliances and fragmentations from December 2006 to December 2011. Our analysis suggests that violence is a consequence not only of the law enforcement actions, but also of the fragmentation and cooperation within and between private groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Levels of violence in Mexico has increased substantially since the implementation of the war against organized crime in 2006. Because the rise of violence was observed after the government implemented its military operations, some authors (Merino 2011; Guerrero-Gutiérrez 2012; Escalante 2013; Hope 2013, 2014) have argued that the introduction of the federal forces to fight criminal groups was the primary cause of the violence boom. This paper adds to the existing literature by analyzing the mechanisms of fragmentation and cooperation within and between criminal groups to better understand the relationship and causality between the implementation of governmental repressive measures against organized crime and the rise in violence.

Previous literature has suggested that violence is caused by the government response to organized crime. Some mechanisms have been explored to explain this relationship. For example, Calderón et al. (2015), Osorio (2015) and Phillips (2015) suggest that repressive law enforcement policies (killing or arresting kingpins or lieutenants) cause fragmentation of groups and furthermore increase violence. Atuesta and Ponce (2016) posit that the implementation of law enforcement policies increases the number of active criminal groups, and consequently influences the level of violence between criminal groups. Rios and Shirk (2011) analyze the power vacuum caused by law enforcement policies that has been translated into an escalation of violence. Other reasons given to explain the boom in violence in Mexico have included the political changes observed in the country since 2000 with the end of the PRI hegemony (Grayson 2011; Snyder and Duran-Martinez 2009); changes in the international arena—mainly the closure of the Caribbean route to traffic Colombian cocaine (Hope 2013); and the regulatory environment in which the organized crime groups operate (Cory et al. 2012).

This article looks to a new perspective of the same phenomenon, by looking how the dynamics of fragmentation and alliance formation, irrespective of concrete government interventions, and the changeable, competitive and violent nature of criminal groups, also escalated violence. By analyzing how the main cartels in Mexico have evolved, we see that they have fragmented – as groups split – and cooperated – i.e., formed alliances – in order to survive. We examine this evolution using a dataset gathered by the Drug Policy Program of the Center for Economic Research and Teaching (CIDE)Footnote 1 (hereafter PPD Dataset). We use the PPD Dataset with two main purposes: first, to identify the main fragmentations and alliances in the organized crime structure from 2007 to 2011; second, to analyze the correlation between each of the fragmentation and cooperation events with the levels of violence.Footnote 2 For the first time, we are able to attribute homicides to specific groups, allowing us to draw conclusions regarding the proportion of violence that is caused by a fragmentation or by the creation of an alliance (for details about the PPD Dataset, see Atuesta et al. 2016).

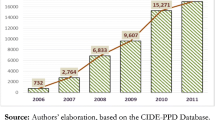

Our results suggest that criminal groups cooperate through alliances and become fragmented depending primarily on their relation with other groups, the period of time analyzed, and the geographical location of their operations. During the five years examined (2007–2011), the structure of organized crime evolved from being comprised of five visible groups participating in less than 20 violent events in 2007 to nearly eighty identified cartels, gangs, and small organizations, participating in more than a thousand events in 2011.Footnote 3 Fragmentation and cooperation are inherent to the nature of organized crime and have represented the criminal groups’ response to law enforcement strategies. Results also suggest a relationship between law enforcement actions (for example, a leader’s death or incarceration), the evolution of the group (i.e., offspring emancipation), and the number of homicides attributable to the affected group.

The main contribution of this work comes from the detailed information used for the analysis. The information gathered from the PPD Dataset, and the corresponding analysis, corroborate previous qualitative studies of organized crime in Mexico. However, this is the first time that the data available provide detailed information on the cooperation and fragmentation of groups, allowing us to conduct an in-depth analysis of the evolution of organized crime and, thus, an analysis of the evolution of violence in Mexico.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section two offers a theoretical framework for studying fragmentation and cooperation. Section three introduces a historical overview of the evolution of the organized crime in Mexico making emphasis on the time periods where fragmentations and alliances are observed. Section four provides a typology of the different fragmentations and alliances, and analyzes the effect these forces have on the level of violence. Finally, section five concludes with an argument that fragmentation and cooperation are determinants for violence, and the primary reason why the government should carefully modify its actions to stop altering these forces.

Fragmentation and cooperation of criminal groups

This section reviews the literature regarding intra-state (i.e., civil war) and inter-state wars in order to analyze conflicts not only through the relationship between criminal groups and the government, but also through the interactions between different criminal groups. While inter-state wars are defined by the Human Security Report Project as conflicts fought by two or more states, Small and Singer define a civil war as “any armed conflict that involves military action internal to the metropole, active participation of the national government, and effective resistance by both sides” (as cited by Sambanis 2004). Although we do not classify the Mexican situation as civil war per se, we use this literature- both on inter- and intra-state conflicts- as a matter of analogy to explain organized crime developments in Mexico.

Alliances and cooperation have been studied primarily in the context of inter-state wars. Three lines of research have been explored in this literature: (i) the relationship between alliance formation and war; (ii) the motivation for formation of alliances; and (iii) the reliability of alliances (Smith 1995). Cooperation has also been explored in the civil war literature by examining the rationality of self-interest individuals to get involved in an alliance, and the role of reputation and signaling on the formation and reliability of alliances (Hugh-Jones 2013; Powell and Stringham 2009).

The civil war literature has also studied group fragmentation, by analyzing how fragmentation dynamics affect the level of violence or the outputs of intra-state conflicts. Pearlman and Gallagher-Cunningham (2012) studies the complex behavior among factions, concluding that coalition building is more prompt to fragmentation than unitary groups. Other authors such as Gallagher-Cunningham et al. (2012) and Bakke et al. (2012), analyze how fragmentation increases violence and affects the duration of war. The civil war literature shows mixed results regarding the effect of fragmentation in conflict: while some authors argue that fragmentation extends the duration of war and increases violence (Gallagher-Cunningham et al. 2012), some others suggest that fragmentation events cluster at the end of conflict and induce factions to negotiate peace settlements (Findley and Rudloff 2012).

Although it is difficult to prove causality between the formation of an alliance and the probability of war, alliances are understood as endogenous to the evolution of conflict and violence. Levy (1981), in the context of inter-state wars, suggests that the type of alliance matters on the evolution of violence; other studies (both in intra- and inter-state wars literature) argue that it is the credibility and the information provided by each of the parties that determines violence (Smith 1995; Gallagher-Cunningham 2013). For Smith (1995), when two or more states decide to cooperate, the balance of power changes, causing other parties to refrain from attacking or retaliating. However, because alliances are costly, actors may give incomplete or false information regarding their willingness to cooperate (Smith 1995; Hugh-Jones 2013). This situation creates instability at the moment that cooperation is needed, making alliances unreliable in most cases. Cooperation, then, is understood to be an altruistic measure, since self-interested individuals may choose to cooperate instead of retrenching individually. This situation has been explored not only in alliances among countries (Hugh-Jones 2013), but also in civil war contexts, with cooperation agreements among private groups (Leeson 2006).

In the context of civil wars, alliances allow groups to survive for longer periods of time (Levy 1981). When groups become weakened, either because they were targeted by the government (Rudloff and Findley 2016; Bakke et al. 2012; Gallagher-Cunningham et al. 2012) or via clashes with rivals, the formation of an alliance is an opportunity to recover and survive for longer periods of time. However, if the alliance is unreliable, or the individual interests of the members differ, the cooperation might not last long and fragmentation can occur.

Fragmentation can result not only when a group disintegrates, but also when some factions of the same group become independent (Gallagher-Cunningham et al. 2012; Gallagher-Cunningham 2013). These independent groups should be analyzed not as unified organizations, but rather as sets of factions with different interests and a common objective (Gallagher-Cunningham et al. 2012; Findley and Rudloff 2012; Gallagher-Cunningham 2013). According to Gallagher-Cunningham et al. (2012), a “group is often a collection of factions (…) Each group is comprised of ‘factions’ which are organizations that claim to represent the interests of the group in the struggle for greater self-determination. Factions can be armed groups, paramilitary organizations, political parties, or civic organizations.”

Figure 1 depicts these interactions graphically. In the first mechanism, the fragmentation of groups, caused by law enforcement policies or by clashes with the competition, debilitates factions that cannot survive without the creation of an alliance. As such, it is in the interest of debilitated actors to cooperate (Findley and Rudloff 2012). The second mechanism is observed when an alliance is broken either because different factions have different interests (Bakke et al. 2012); because the common purpose of the alliance disappears (i.e., the existence of a common enemy); or because the costs of cooperation increase. The rupture of the alliance generates separate factions and further fragmentation.

When a group is formed as a coalition, it is more probable that different factions have different interests, and that the unity of the coalition will be threatened by external factors such as the disappearance of a common enemy or a change in the balance of power in a specific territory.Footnote 4 In these cases, fragmentation is more likely than when the organization has strong ties and institutions, and when it is created with a unique command (Bakke et al. 2012).Footnote 5 A fragmentation, then, can be observed in two situations: first, with the split of a coalition (formed by different groups) and second, with the disintegration of a group. In the first case, the groups that were members of a coalition become independent. In the second case, the new factions of the disintegrated group create new organizations with independent objectives.

Bakke et al. (2012), in the context of civil wars, proposes three dimensions in which a fragmentation is analyzed: (i) organizations with a greater number of factions have higher chances of fragmentation; (ii) more centralized organizations impose more discipline and rules, making fragmentation less likely; and (iii) organizations with more institutions and rules are more stable and have lower chances of fragmentation.

Having discussed the determinants of cooperation and fragmentation, one important question is whether these forces generate greater levels of violence or perpetuate armed conflicts. The literature offers mixed conclusions regarding the effect of fragmentation and cooperation on violence and conflict. Levy (1981), in the context of inter-state wars, argues that more permanent alliances, compared to ad hoc alliances, actually increase the probability of war. Findley and Rudloff (2012), when analyzing violence in civil wars, suggest that fragmentation debilitates groups, and such groups are more likely to accept peace settlements and to terminate conflicts. Rudloff and Findley (2016), also in the civil wars context, look beyond the end of a conflict, arguing that a peace settlement achieved with fragmented factions tend to be less permanent than any other agreement, suggesting that violence would increase when peace is broken. Staniland (2012) posits that lethal competition between groups (in intra-state wars) can lead to defection; moreover, those surviving but weakened end up searching for state protection. In addition, non-state group fragmentation could allow the government to divide leaders and co-opt them in order to sue for peace (Driscoll as cited by Pearlman and Gallagher-Cunningham 2012).

In this article we analyze the different fragmentations and alliances observed in the organized crime structure in Mexico using the theoretical framework described above. Moreover, we analyze the effect that these two dynamic forces have on the evolution of violence, and consequently on the perpetuation of the war against organized crime in Mexico. We test two theoretical arguments.

-

(i).

Fragmentations of criminal structure, can occur in three different ways, as a disintegration of already established alliances, because factions of a unitary group become independent, or because successions within the same organization debilitate the unity of the group. In each case, the level of violence increases as new competitive groups fight for controlling the territory.

-

(ii).

Alliances are created because groups debilitated after a fragmentation decide to collaborate with each other, because they are facing a common enemy, or because they want to control territory. Once these external factors disappear, the cooperation between groups also tends to disappear. However, alliances allow criminal groups to survive for longer periods of time, and their effect on violence could be positive or negative, depending on the conditions under which the cooperation takes place.

To test these arguments empirically, we identify fragmentation and cooperation events in the evolution of Mexican organized crime. Then, using a typology for fragmentations and alliances, we test their effect on the level of violence in the country.

Fragmentation and alliances in the Mexican organized crime structure

In what follows, a brief history about the formation of the main cartels in Mexico is provided with the objective of identifying fragmentations and alliances in the organized crime structure. We use the PPD Dataset from which we are able to identify at least 200 different groups from 2007 to 2011. These groups communicate with each other through narcomessages left next to the executed bodies, and we use this information to identify rivalries, alliances, and fragmentations.Footnote 6

Mexican cartels are usually composed by different groups from which we can identify the following:

-

Leaders: capos that lead or manage the cartel.

-

Armed wings: groups with the objective of protecting an organization, business, or territory. They are under command of the main cartel and are not involved in drug trafficking. Instead, they concentrate on attacking and defending territory.

-

Operator/gunmen: operators are individuals that are responsible for turfs, while gunmen are hired to kill and/or protect the organization.

-

Local bands: these bands are not created by the cartel; however, they are “hired” to lead local fights. They usually operate local illegal markets with the protection of the cartel.

-

Bands originated by or with the support of the cartel: the cartel contributes to the formation of these bands, either by fragmenting and leaving a power vacuum, or by directly supporting their creation.

-

Alliances: agreements between two or more independent groups to attack a common enemy, to avoid violence in a specific territory, or to pursue (temporarily) common interests.Footnote 7

The timeline starts with the Guadalajara Federation (Fig. 2). After his incarceration in 1989, Felix Gallardo, the Federation leader, wanted to divide the drug business into seven territories under the Guadalajara’s umbrella (Astorga 2005; Hernández 2012). However, this division was not followed, and instead, three organizations were born: the Gulf Cartel in Tamaulipas, the Juarez Cartel in Chihuahua, and the Tijuana Cartel in Baja California. Further fragmentation was observed when the Sinaloa Cartel and the Beltran Leyva Organization (OBL) born as emancipations of the Juarez Cartel; and Los Zetas became independent from the Gulf Cartel.

The Carrillo brothers led the Juarez Cartel for 20 years: Amado Carrillo until 1997 and Vicente Carrillo until his incarceration in 2009. According to Valdés-Castellanos (2013a, b), the Juarez Cartel had the protection of public servants from the municipal level to the military forces, who served as a surrogate personal army. Nevertheless, La Linea , Los Aztecas and the Nuevo Cartel the Juarez appear as armed wings of the Cartel. The evolution and the composition of the Juarez Cartel from 2008 to 2011, is observed in Fig. 3.

Guzmán Loera, El Chapo, with his partners, El Mayo Zambada y Nacho Coronel, constructed a drug empire known as the Sinaloa Cartel, after he emancipated from the Juarez Cartel. Although he was incarcerated several times since 1994, he was able to continue leading the organization until his final capture in 2016.Footnote 8

Although its complex structure, and attacks from several enemies, the Sinaloa Cartel has survived since its origins in 1994, by implementing an “outsourcing” model in which different groups were allowed to be part of the organization. Armed groups as Gente Nueva, Los M’s and Los Pelones began protecting the Cartel in 2007 and 2008 when the Sinaloa Cartel was locked in deadly battles against the Tijuana and Gulf Cartels, as well as the Beltran Leyva brothers. By 2009 and 2010, the Sinaloa Cartel had expanded to include more groups and had become more dispersed, involving the participation of more than 13 armed wings, related and originated bands, as shown in Fig. 4.

Similar to El Chapo, the Beltran Leyva brothers (Arturo, Hector and Alfredo) got involved in the drug trafficking business by working as hitmen and transporters for the Juarez Cartel, and later for the Sinaloa Cartel.Footnote 9 When in 2008, Alfredo was captured during a military operation, the brothers suspected that El Chapo had betrayed them. This event caused a rupture and the formation of the Beltran Leyva Organization (OBL) as an independent organization, contributing to the creation of several bands and leaders associated with the Beltran Leyva brothers (See Fig. 5).

Two main fragmentations were observed from the OBL. The first one was led by Edgar Valdez Villareal “La Barbie” who was hired by Arturo Beltran as an operator when the OBL worked for El Chapo. When Arturo was killed in December 2009,Footnote 10 La Barbie did not recognize Hector as a successor and decided to split from the OBL, forming his own organization in 2010. The second fragmentation was organized by Hector Beltran, who created a new organization with the remnants of the OBL, and named it “ Cartel del Pacifico Sur (CPS) ” .

The Gulf Cartel,Footnote 11 in Tamaulipas, also suffered from fragmentations and alliances, as shown in Fig. 6. The Cartel’s leadership changed hands several times, until Salvador “Chava” Gomez and Osiel Cardenas decided to jointly command the organization. However, Osiel killed Chava in 1999 earning the nickname of “Mata amigos” (Friend killer), and during the following years, Osiel focused on gaining dominion of the Gulf Cartel, and creating Los Zetas for protection. Los Zetas - composed of former members of a specialized unit in the army, and former members of the Guatemalan special military group - helped the Gulf Cartel to expand their territory even across the southern border to Guatemala.Footnote 12

In September 2012, the Gulf Cartel’s leader, El Coss, was incarcerated; and in January 2013, his successor was murdered, while in August of the same year, the new leader was arrested. After this lack of leadership and with a violent offshoot (Los Zetas) becoming a dangerous enemy, the organization faced instability and a power vacuum.

On the western side of the country, the state of Michoacán became a valuable territory for the drug business because of its fertile lands for poppy production, and because it has the Port of Lazaro Cardenas, main entrance from the Pacific Ocean, and exit to Asia and the rest of North America. For years, the Millennium Cartel (also called the Valencia Cartel) controlled the drug traffic in the state, maintaining a low profile. It was not until 2001 that violence arose, when Los Zetas arrived in Michoacán to control all illegal operations in the area. The Millennium Cartel defended itself, trying to protect their territory, but the military superiority of Los Zetas overcame the Millennium’s resistance.Footnote 13

Los Zetas, after controlling the territory, trained local people (mostly ex-members of the Millennium Cartel), and began extorting the local society. These events were the main cause for the creation of La Familia Michoacana in 2006, with the objective of expelling Los Zetas from the state, and attacking their main business: methamphetamine.

La Familia had two interesting and unique characteristics: its territorial expansion, not only in Michoacan but also to the neighboring states such as Guanajuato and Guerrero; and the principles on which they operated. Members of La Familia held strong religious principles, including a feeling of “social duty.” La Familia’s objective was not only to rid the territory of Los Zetas, but to provide protection for the civilian population as well. However, as violence intensified in Michoacán (basically because of the rivalry of La Familia and Los Zetas), several groups arose, claiming to defend the society from La Familia. Among these “self-defense” groups are El Vengador del Pueblo (The Town’s Avenger), El Señor Justicia (Mr. Justice) and Pueblos Unidos (United People).

The leader of La Familia, El Chayo, was killed in 2014 during a military operation, causing internal fights in the organization. While some decided to form an alliance with La Resistencia, others formed the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (previously called Mata-Zetas and the product of an alliance with the Sinaloa Cartel). In 2011, “La Tuta” and Enrique Plancarte left La Familia and formed Los Caballeros Templarios (see Fig. 7). But in February 2015, “La Tuta” was captured by the federal police and Los Templarios debilitated. According to Insight Crime (2015a), La Familia remained active due to the weakness of Los Templarios.

From this historical description of organized crime in Mexico, we identified the different moments in which groups are collaborating and fragmenting. Figure 8 shows these alliances and fragmentations in a chronological order, while Fig. 9 depicts these events and correlates them with the number of homicides observed in the country. Although it is not possible from the graph to attribute causality between specific fragmentation and cooperation events and the increasing violence, we observe a violence peak after specific events. For instance, after the fragmentation of the OBL and the emancipation of La Barbie in 2010, or the alleged death of La Familia’s leader and the creation of Los Templarios in 2011. The next section categorizes these events by proposing a typology based on the theoretical framework described in section 2, and analyzes the homicides that are attributable to specific fragmentation and cooperation events.

Typology of fragmentations and alliances in the structure of organized crime in Mexico and their impact on the level of violence

We identify four types of fragmentations and three types of alliances, following the theoretical arguments presented in section 2. The state has played a role in most of the fragmentations and alliances, since in several cases the main reason for a group’s debilitation is typically the capture of its leader. We then specifically exclude a category related to law enforcement. Once the different episodes observed in the evolution of organized crime have been categorized into fragmentations and alliances, we analyze the effect that these two forces have on the level of violence.

We identify four types of fragmentations by cause: (i) loss of reputation; (ii) through heterogeneous factions; (iii) successions within the same organization; and, (iv) broken alliances. The three types of alliances include those seeking: (i) to control territory and obtain protection; (ii) to shore up factions weakened after a fragmentation; and (iii) to confront a common enemy. However, these categories are not exclusive. For instance, an alliance could be formed in order to strengthen already debilitated groups and to confront a common enemy. A fragmentation, on the other hand, could be caused because an alliance was broken, and also because the incarceration or killing of a leader debilitated the group and factions began acting independently.

To analyze the correlation between each of these types with the levels of violence in Mexico, we use as indicator the homicides identified in the PPD Database that are attributable to specific groups, and the proportion of these killings where at least two groups are identified as rivals (usually after a fragmentation), or as allies (evidence of cooperation). Specifically, in the “executions” category, the PPD Database identifies groups that were tied to specific events, either because they signed or directed the narcomessages left next to the executed bodies, because a member of a specific group was killed or arrested, or because the governmental authorities had specific information linking the event to a criminal group.Footnote 14

Types of fragmentations

Fragmentation by loss of reputation

Fragmentations by loss of reputation are caused by the betrayal of one of the members of a group or alliance, causing the failure of the alliance. In a cooperation framework, reputation of the alliance is seen as a public good; when the alliance cannot build a reliable reputation, rivals are not deterred from attacking a “failed cooperation.” As a consequence, other members do not have incentives to participate in the cooperation system (Hugh-Jones 2013). When alliances are broken, the group’s reputation and the levels of violence are altered. Groups bargain with each other through reputation and the betrayal of already formed alliances, significantly affecting the reputation of the group and dramatically changing the organized crime scenario. There are two fragmentations by loss of reputation observed on the evolution of the organized crime in Mexico: the first is related to the Sinaloa Cartel and the second to the Gulf Cartel.

El Chapo, head of the Sinaloa Cartel, intended to build a Federation in which the participation of other organizations — such as the Beltran Leyva Organization — was allowed under the supervision of the main leadership. However, El Chapo directly undermined the establishment of the Federation by attacking his enemies and betraying his allies. The betrayal of El Chapo to the Beltran Leyva brothers fragmented the agreement previously established between the Sinaloa Cartel and the brothers, driving them to create their own organization (the OBL), and later on to create an alliance with the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas to confront Sinaloa. A second example is observed in the Gulf Cartel. The agreement between Osiel Cardenas and Salvador (Chava) Gómez for the creation of a group was terminated when Osiel killed Chava to remain the sole leader of the organization.

Fragmentation by loss of reputation increases violence between groups. Figure 10 shows the total number of deaths associated with the OBL and the proportion of these deaths that are attributable to the rivalry of the OBL and the Sinaloa Cartel, after El Chapo betrayed the Beltran brothers. After its separation from the Sinaloa group in 2008, the number of deaths associated with the OBL grew from 21 in 2008 to 510 in 2011. In 2009, the year in which the OBL activity increased substantially, messages from the OBL accusing El Chapo of being a traitor began appearing. In terms of territorial expansion, one year later the clashes were not only concentrated in the north (Sinaloa, Sonora, and Durango) but also in the center (Morelos) and the south (Guerrero) of the country. In 2011, the clashes between these two groups continued, but because of the appearance of La Barbie, the OBL had to distribute its efforts amongst more enemies. From 2008 to 2011, the clashes between the Sinaloa Cartel and the OBL left 387 dead.

Fragmentation by heterogeneous factions

As established in the literature of organizations, a group cannot be analyzed as a single unit, as each of its members (or factions) have different ways of addressing the same problem or operationalizing the same objectives (Scott 2013). In other words, a group should be understood to be a coalition of heterogeneous interests that share a common goal (Gallagher-Cunningham et al. 2012). When this common goal disappears, factions seek their independence, causing fragmentation. Both the Gulf Cartel and La Familia Michoacana suffered from fragmentations, explained by the existence of heterogeneous factions. Typically, in this type of fragmentation, a unique group is fragmented in different factions and new groups are born out of the split.

Osiel Cardenas, leader of the Gulf Cartel, decided to create a specialized group, Los Zetas, for his personal protection. However, the alliance was broken when Osiel was incarcerated in 2003. Los Zetas, an organization with its own structure and military rules, decided to break away from the Gulf Cartel because they had different interests and refused to recognize the new Gulf Cartel’s leaders. After this fragmentation, a bloody war between the two groups was initiated, including turf wars against other groups including the Sinaloa Cartel. Los Zetas were an armed wing of the Gulf Cartel without being properly independent. However, because they have their own structure, we classify them as an independent faction.

A second example of fragmentation by heterogeneous factions is observed in La Familia Michoacana. The alleged assassination of the leader of La Familia, El Chayo, in 2011 caused internal strife in the organization. While some decided to form an alliance with La Resistencia, others formed Los Caballeros Templarios. In February 2015, when the leader of Los Caballeros Templarios was captured, the portion of La Familia not under the command of Los Templarios found a new ally with the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG). La Familia ended up fragmenting into three different groups after its leadership decapitation: La Resistencia, Los Caballeros Templarios, and the CJNG, with Los Caballeros Templarios being the only new group created directly as a faction of La Familia. The other two fragmentations were already extant groups.

Figure 11 depicts the number of deaths attributable to La Familia and the proportion of these deaths caused because of the fragmentation of La Familia and Los Templarios. Before 2010, La Familia had clashes mainly with Los Zetas, fighting against their entrance to Michoacán. In 2010, La Familia fragmented and Los Templarios was born. Three homicides in Guerrero and 17 homicides in Michoacán were due to clashes between La Familia and Los Templarios in 2011. Although this directed violence continued in 2012, the PPD Dataset does not provide information after 2011.

Fragmentations by successions within the same organizations

A third type of fragmentation is observed when the leader of an organization dies or is incarcerated, and a new leader arises within the same organization. Sometimes these transitions are extremely violent, as members of the same organization fight to obtain power. In other cases, the succession is not accompanied by violence, but the concurrent changes of leadership nonetheless weaken the structure of the group, producing further fragmentation. Usually these fragmentations are caused by law enforcement policies, but not as a result of being targeted by different organizations. In fact, their main threat comes from inside the organization. As Bakke et al. (2012) described, “infighting is potentially one of the most significant consequences of fragmentation. Infighting undermines a movement’s capacity for collective action and diverts energy away from the pursuit of public, political aims and towards the pursuit of private advantage.” We identify three fragmentations by succession in the period analyzed: one in the Gulf Cartel and two in the OBL.

We already categorized the fragmentation by succession inside the Gulf Cartel as a fragmentation by loss of reputation. The assassination of Chava weakened the Gulf Cartel, and Osiel had to hire Los Zetas not only to protect himself from external enemies, but also for his personal protection in an already struggling organization. The incarceration and killings of the Gulf Cartel’s leaders continued, and Los Zetas emancipated from the Gulf Cartel in 2010 to pursue their own interests.

The inevitable fragmentation of the OBL gave birth to two main factions: La Barbie and the CPS. With the support of La Resistencia, Los Zetas, and its armed wing “Los Rojos,” the CPS fought against La Barbie in Morelos and Guerrero. Moreover, the former OBL’s armed wings began fighting with each other, suggesting that they were no longer aligned with the brothers: Los Charritos were fighting with La Mochomera, a remnant group from the OBL, and Los Mazatlecos allied themselves with Los Zetas, most likely to fight the Sinaloa Cartel.

The PPD Dataset allows for the tracking of Los Zetas’ fragmentation from the Gulf Cartel. During 2008, the names Los Zetas and the Gulf Cartel were used almost interchangeably. In fact, most of the attributable messages left next to the bodies were signed “Golfo-Zetas.” However, in 2010, the data suggest an important change: messages began to be signed either by the Gulf Cartel or by Los Zetas. In most of the cases, they appeared as independent groups, with one the victim and the other the perpetrator. Clashes between them were observed all over the country, including the states of Coahuila, Nayarit, Nuevo Leon, Oaxaca, San Luis Potosi, Tabasco, Tamaulipas, and Zacatecas. This fragmentation has been responsible for at least 144 executions since 2010 (Fig 12).

Fragmentation caused by a broken alliance

The last type of fragmentation identified in the literature is the split of an alliance. Usually, an alliance allows debilitated groups to survive longer. However, as the alliance is formed by groups with their own structures, institutions, and rules, often these coalitions do not last long, producing further fragmentation. As posited by Pearlman and Gallagher-Cunningham (2012), “groups with unified leadership bodies may weather the storms of insurgency, yet those under the leadership of a coalition of factions are much more likely to divide.” We identify three fragmentations in this category: the first is the division between the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas. The second two are related to the Juarez Cartel: first when the alliance to El Chapo was broken, and second comprises the emancipation of La Linea.

The fragmentation of the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas was already classified as a fragmentation by heterogeneous factions when Los Zetas were analyzed as a faction of the Gulf Cartel. However, even though the only reason why Los Zetas were created was to protect the Gulf Cartel, these two organizations could be analyzed as two different organizations, each with their own structure and rules. In fact, Los Zetas communication (through narcomessages) suggests that they were operating on their own in most of the territory, following their own strategies. In this sense, we can study the fragmentation of these two groups as a broken alliance where two already existing groups became independent.

Two emancipations are observed in the Juarez Cartel. The first one was when El Chapo became independent from Juarez to create the Sinaloa Federation. This “broken alliance” between El Chapo and Juarez increased violence exponentially between the groups. The second rupture is documented as the emancipation of La Linea from the Juarez Cartel. La Linea was born as the main armed wing of the Juarez Cartel with the objective of fighting the Sinaloa Cartel and defending the Juarez territory. An article published by the Mexican journal Milenio (Mosso 2013) mentions the intent to create a new group, Nuevo Cartel de Juarez, but further incarcerations of its leaders and the decreasing power of La Linea as consequence of military attacks left the future of the organization uncertain.

The violence caused by the fragmentation of the Juarez and Sinaloa Cartels is observed in Fig. 13. For instance, from 1151 deaths attributable to the Juarez Cartel in 2010, 1026 were against the Sinaloa Cartel (or any of its allied groups). In most of the homicides in which the Juarez Cartel is identified, a message left next to the executed bodies was signed by La Linea (since 2010) or mentioned the name of Vicente Carrillo. The number of events in which the Juarez Organization was identified decreased dramatically in 2011, and even though the data do not capture the activity from the group Nuevo Cartel de Juarez, this group seems to be a new faction, or the same group with a new name (PGR 2013).

Types of alliances

Alliances among groups to control territory and to obtain protection

The most common type of alliance in the evolution of organized crime in Mexico is represented by groups willing to control territory and obtain protection. The control of a specific territory allows criminal groups to ensure profits from the drugs produced or sold there, or to benefit from rents obtained from controlling the routes used to traffic drugs and other illegal goods to the U.S. As with fragmentation, law enforcement policies can debilitate groups, and the creation of an alliance in most of these cases is the only way groups can survive for longer periods of time. From our analysis, of the ten alliances recognized during the period, eight are categorized as alliances with the objective of controlling territory and obtaining protection. A brief description of these alliances is included below:

-

Osiel Cardenas and Chava Gomez created the Gulf Cartel and controlled the state of Tamaulipas for the trafficking of illegal drugs to the U.S.

-

El Chapo and the Juarez Cartel joined forces to expand El Chapo’s access to the local market of Chihuahua.

-

The Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas banded together to provide protection to the Gulf Cartel, and to allow its expansion to southern and western territories.

-

El Chapo and Mayo Zambada created the Sinaloa Cartel to control the Sinaloan territory.

-

The OBL and Los Rojos combined, after the OBL was debilitated (because of its fragmentation with the Sinaloa Cartel), to fight against Sinaloa and maintain control of their territory.

-

The Gulf Cartel and La Familia Michoacana merged to recover the state of Michoacan after the entry of Los Zetas.

-

Los Mazatlecos allied themselves to a stronger group, Los Zetas, to stay active for a longer period of time and to fight the Sinaloa Cartel.

-

La Resistencia, Los Zetas, and the CPS allied with one another after the fragmentation of the OBL to fight La Barbie. Hector Beltran Leyva was debilitated after the fragmentation of the OBL and the alliance with La Resistencia and Los Zetas was the only way to keep control of his territory.

Figure 14 shows the efforts of different groups to control Michoacán, where La Familia allied with the Gulf Cartel to expel Los Zetas form the state. From 516 homicides reported in Michoacan in 2009, 264 were attributable to La Familia and 57 to clashes between La Famila (allied with the Gulf Cartel) and Los Zetas. La Familia tried to control most of the neighboring states of Michoacan, including Guerrero, Querétaro and the state of Mexico. In the case of Michoacán, the debilitated group of La Familia produced further fragmentation, creating Los Caballeros Templarios. This emancipation led to 68 homicides attributable to Los Templarios in 2011, who were also fighting to gain control of the state over La Familia.

Alliance of factions weakened after a fragmentation

Most of the fragmentations identified in the previous sections were followed by a cooperation agreement between groups. As stated in the theoretical framework, an alliance is the only option groups have to strengthen themselves after fragmentation, to fight their enemies, to control turf, and to obtain political relevance. Since these forces are dynamic, and most of the groups lack reputation because of their changeable nature, these alliances do not last long and are usually followed by further fragmentation (Hugh-Jones 2013; Powell and Stringham 2009). We identified three alliances in this category: the alliance between the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas; the alliance between the OBL and Los Rojos; and the cooperation agreement between La Resistencia, Los Zetas, and the CPS.

The first two identified alliances in this category are groups that decide to create an armed wing. We call these “alliances” because they can be identified as independent groups with a well-defined structure, rules, and institutions. Even if they were created as part of an already existent organization, they were autonomous in their modus operandi and committed acts attributable only to them, and not to the alliance or to the primary group. The Gulf Cartel was debilitated, internally and externally, and the only opportunity for survival was to ally with Los Zetas in exchange of protection.

A similar situation is observed with the OBL and Los Rojos. After the OBL factionalized, intragroup violence increased between different factions. What was left of the dismembered organization tried to align all the members and consolidate power using the signature “El Jefe de Jefes,” and the name of “El color más fuerte,” indicating an alliance with the armed wing, Los Rojos.

Finally, as explained in the first type of fragmentation, a debilitated Hector Beltran Leyva created the CPS after the fragmentation of the OBL. By entering an alliance with La Resistencia and Los Zetas, he was able to fight against La Barbie and keep control of his territory. This alliance is observed in Fig. 15. The violence attributed to the OBL increased from 2008 to 2010, passing from 21 to 596 homicides, and decreasing to 510 in 2011. Since 2009, the year in which the fragmentation took place, a sharp uptick in violence attributable to the alliance of the OBL (through the CPS) and Los Zetas can be observed, mainly against the rivalry organization of La Barbie.

Alliances to confront a common enemy

Since the structure of the organized crime in the country is ever-evolving, there have been episodes in which the governmental forces debilitate or change the status quo of groups active in a specific territory. As a result, other groups invade and try to control the turf. In order to avoid the invasion of new groups, existent organizations, even if former rivals, create alliances to fight a new common enemy. Because these alliances are created only in response to an external threat, they often do not last long. As soon as the external threat disappears, these groups, which usually do not share common interests or objectives, tend to break up the agreement (Hugh-Jones 2013). These temporary alliances are very common in Mexican organized crime. In the period analyzed, we identified six alliances formed to confront a common enemy:

-

i.

the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas to confront the Sinaloa Cartel;

-

ii.

the Gulf Cartel and La Familia Michoacana to confront Los Zetas who wanted to enter Michoacán;

-

iii.

the Juarez Cartel, the OBL and Los Zetas to confront the Sinaloa Cartel;

-

iv.

Los Mazatlecos and Los Zetas to confront the Sinaloa Cartel, specifically the armed wing of Los Aztecas;

-

v.

the OBL and Los Zetas to confront the Sinaloa Cartel; and

-

vi.

La Resistencia, Los Zetas and the CPS to confront La Barbie.

In three of the six alliances identified in this section, Los Zetas cooperated with other groups to fight Sinaloa. Even when Los Zetas were part of the Gulf Cartel, they received and sent attacks to the Sinaloa Cartel; these clashes remained even after their emancipation. Once they became independent, the fight was taken up against the Sinaloa Cartel’s armed wing, Gente Nueva. From 2009 to 2011, this intense war accounted for several incidents in the organized crime scene, affecting areas from north to south. However, after their split from the Gulf Cartel in 2010, the clashes with their former bosses gained significance; as such, the number of violent events where the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas were identified as rivals exceeded the number of events in which Los Zetas had clashes with the Sinaloa Cartel. In the latter case, 123 killings were identified in 2010 and 2011, while for the former, this figure was 144 for the same period of time. Figure 16 compares the number of homicides caused by the clashes between Los Zetas (and their different alliances) to confront Sinaloa, with those homicides resulting from their other rivalries (i.e. against the Gulf Cartel since 2010, and against La Familia since 2009).

Discussion

Table 1 shows the proportion of deaths attributable to fragmentations and alliances from the total number of attributed homicides to specific groups. Only fragmentations and alliances from 2007 to 2011 are analyzed, since the data are available only for those five years. The groups with the greatest number of attributed homicides are Sinaloa, followed by the Juarez Cartel and the OBL. From these fragmentations, the most costly in terms of number of homicides are the fragmentations between the Sinaloa Cartel and the Juarez Cartel (1922 homicides), followed by the OBL vs. Sinaloa (377 homicides), and the Sinaloa vs. Zetas (203 homicides). On the other hand, the alliance between OBL and Los Zetas after the OBL fragmentation produced 139 homicides from 2009 (11% and 9.6% of Los Zetas and OBL attributed homicides, respectively).

The most costly fragmentations, in terms of violence, are the broken alliance between the Sinaloa Cartel and the Juarez Cartel, and the loss of reputation between the Sinaloa Cartel and the OBL. Although the output in terms of violence of these two events is not evidence enough to conclude that these two types of fragmentations are costlier than the others, we can suggest that the peak observed in violence is a consequence of the broken trust between both groups. And even though alliances seem not be as violent as fragmentations, when an alliance is broken, violence seems to upsurge to levels greater than those before the formation of the cooperation agreement.

In terms of how costly these fragmentations are for specific groups, we analyze the proportion of homicides attributable to the fragmentation from the total homicides in which the group was implicated. For 2010, the fragmentation between Sinaloa and Juarez represented 89.1% of the total attributed homicides to Juarez, and only 64% of the attributed homicides to Sinaloa, suggesting that the fragmentation was more costly to Juarez than to Sinaloa. A similar situation is observed with the fragmentation between Sinaloa and OBL: for the former, the fragmentation represents only 12% of their total homicides, while for the latter, it was 26%.

The Sinaloa Cartel, with 3059 homicides attributable to its actions, was involved in two fragmentations that represent 75% of their total attributable homicides: (i) by a broken alliance with the Juarez Cartel; and (ii) by loss of reputation with the OBL. On the other side, the Sinaloa Cartel was the common enemy of different alliances formed between the OBL and Los Zetas; the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas; the Juarez Cartel, the OBL and Los Zetas; and Los Mazatlecos and Los Zetas. Some of these rivalries between the alliances and the Sinaloa Cartel are shown also in Table 1 (Sinaloa vs. Zetas with 203 homicides and Sinaloa vs. Juarez with 1922 homicides).

The dynamics of the relationship between the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas is shown both as an alliance and as a fragmentation. Both groups were allied from 2007 to 2009, and 229 homicides were attributed to this alliance. With their split, in 2010, 144 homicides were attributed directly to the fight between both groups. While the Gulf Cartel benefited more from the alliance (35% of their attributable homicides were conducted under the alliance with Los Zetas), the Gulf Cartel was also more damaged with the fragmentation, with 22% of their homicides directed to Los Zetas (while the fragmentation only represented 11% of Los Zetas’ homicides).

Although both fragmentations and alliances are observed in the PPD Dataset, the number of homicides attributed to fragmentations and rivalries among groups is greater than the number of homicides attributed to specific alliances. This finding does not suggest that fragmentations produce more violence than alliances, but that fragmentations are more “visible” in terms of violence than alliances. Alliances take place in order to control territory or to survive for longer periods of time, but an alliance not specifically direct or attribute its violence to specific groups; only when the target is a common enemy. For instance, the alliance between La Familia and the Gulf Cartel to fight Los Zetas is observed as a rivalry between La Familia and Los Zetas, with 80 homicides attributed to this fight, and also as a rivalry between the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas (during the same period of time), with 144 homicides attributed to this fragmentation.

Conclusions

This paper examined the evolution of organized crime in Mexico, focusing on fragmentation and cooperation as two determinant forces that drive the behavior of criminal groups. Organizations have survived enemies’ attacks (either from private groups or public forces) through cooperation and the formation of alliances. Similarly, groups have evolved by changing their internal structure and creating independent factions. These two forces have marked the structure of organized crime and consequently the evolution of violence in the country.

Although previous studies of fragmentation and cooperation have focused on inter- and intra-state conflict, we use these theoretical frameworks to create a typology of the different fragmentations and alliances observed in Mexico. We identify four types of fragmentations and three types of alliances depending on their main causes and determinants. Although the events analyzed are not exclusive (i.e., an event can be categorized in two or more different types), we use different cases to exemplify the correlation between each of the types and the level of violence attributable to each type.

The results of this article can be summarized in two conclusions. The first one related to the organized crime structure in Mexico, and the second one regarding the relationship between fragmentation and cooperation agreements with the level of violence observed in the country. The results shown in the previous section suggest that the structure of organized crime in Mexico is not static, and criminal organizations group together in order to survive longer, or fragment in order to pursue different interests or to expand their dominion to new territories. By analyzing the different types of fragmentations and alliances we observe that the main criminal groups in Mexico have used these dynamic forces, and consequently, have created new rivalries, have conquered new territories and have become more complex than the original drug cartels observed at the beginning of the 1990s. Nowadays, the structure of organized crime in Mexico is so complex that it is almost impossible to follow each split, revenge or coalition between and within groups. From five visible groups observed in 2007, more than eighty groups were identified in 2011. In the five-year period, we were able to identified more than 200 groups; while some of them appeared only temporarily (active only during one year), some others have changed names and objectives, or have amalgamate with or fragment to other groups.

Moreover, relationships between criminal groups are rarely based on trust, and without the existence of biding laws or contracts to follow, organizations and alliances are weak. Mexican criminal organizations should be understood as groups of different and independent factions that are cooperating temporarily, but once the incentive to cooperate disappear (i.e. disappearance of a common enemy, treason among members to pursue more power, or appearances of new independent objectives), fragmentation will follow, causing severe consequences in terms of violence.

The second conclusion concerns the correlation of these two dynamic forces with the level of violence. The number of homicides attributable to a specific alliance or fragmentation suggests that these forces are costly in terms of violence, and changing the status quo of organized crime increases the level of violence observed in the country. The evolution of organized crime, and consequently the level of violence, cannot be understood only by analyzing the role played by the state on its war against organized crime. In order to provide policies able to reduce violence, the evolution of organized crime has to be studied by observing how criminal groups behave in fluid and surprising ways. Although the government implicitly has supported (or not attacked) specific cartels, law enforcement interventions have triggered (unintendingly) many of the fragmentation and cooperation dynamics observed in organizations’ structures. The beheading of an organization (through the killing or incarceration of its leader) can provoke fragmentation within the group, or produce external competition when other groups try to control the territory. However, law enforcement activities can also lead to cooperation when groups decided to make an alliance to confront the attacks, form horizontal alliances among different cartels (or pax mafiosia), or engage in vertical alliances between small gangs and bigger ones (Polo 1995).

The complex influence of government drug interdiction leads us to suggest that policies that alter the status quo of the organized crime have two primary, violent outcomes: (i) a change in the dynamics between and within groups (understood as fragmentations and cooperation agreements) causing further violence; and (ii) the debilitation of criminal organizations that provides the opportunity for other groups to expand and grow. Offering alternative policies to change these outcomes through law enforcement is not an easy task. However, one important change that should be taken into consideration in the Mexican security strategy is to avoid the military intervention to address public security problems, and instead, consider implementing a reform of the police structure and the legal system. But in order to think about a solution, we need first to understand the nature of the problem and the consequences generated by the current policies. An alternative solution needs to avoid, if possible, these changing dynamics of fragmentation and cooperation, avoiding as well the optimal conditions for the criminal groups to survive and evolve.

Notes

CIDE is a Mexican center for research and higher education specialized in social sciences. More information at http://www.cide.edu/sobre-el-cide/

We are using homicides categorized as “executions” allegedly related to organized crime as proxy for violence. Other indicators of violence can be used (i.e. number of disappearances, extortion, kidnappings, and torture, among others).

The number of events related to organized crime gathered in the PPD Database is greater than these numbers. However, a criminal group is not always identified.

Alliances and coalitions are not the same. According to Smith (1995), an alliance is a nonbinding agreement between two nations. A coalition is a group of nations that fight together in war, with or without a previous agreement.

A unique command allows an organization to be institutionalized, with all factions being represented by the organization (Bakke et al. 2012).

The online appendix provides a detailed description of the groups forming alliances and fragmentations, and a brief description of the PPD Dataset information used for this analysis.

A more elaborated typology for defining alliances is presented in section 4.

El Chapo escaped from jail in 2001, and in 2014, was recaptured. He escaped once again in 2015, and in January 2016 he was captured for the last time.

Based on the profile of the OBL developed by InSight Crime (2015b).

The PPD Dataset is comprised of three categories: confrontations (between criminal groups and the government, or within criminal groups); aggressions (from criminal groups to the government); and executions (violent homicides that are allegedly related to organized crime). From the executions category, 11% of the homicides are “labeled,” i.e., events where a message was left with the executed body. From this percentage, approximately 70% of the messages were attributable (either signed by or directed to specific groups; Atuesta(2016)).

References

Astorga L (2005) El siglo de las drogas: el narcotráfico, del Porfiriato al nuevo milenio. Plaza y Janés, México City

Atuesta L (2016) Narcomessages as a way to analyse the evolution of organised crime in Mexico. Global Crime. doi:10.1080/17440572.2016.1248556

Atuesta L, Ponce A (2016) ¿Cómo la Intervención Gubernamental Altera la Violencia? Evidencia del Caso Mexicano. Working paper, Drug Policy Program, CIDE

Atuesta L, Siordia OS, Madrazo A (2016) La ‘guerra contra las drogas’ en México: Registros (oficiales) de eventos durante el período de diciembre 2006 a noviembre 2011. Working paper. Drug Policy Program, CIDE, 2016

Bakke KM, Cunningham KG, Seymour LJ (2012) A plague of initials: fragmentation, cohesion, and infighting in civil wars. Perspect Polit 10(02):265–283

Calderón G, Robles G, Díaz-Cayeros A, Magaloni B (2015) The beheading of criminal organizations and the dynamics of violence in Mexico. J Confl Resolut 59(8):1455–1485

Cory M, Rios V, Shirk DA (2012) Drug violence in Mexico: data and analysis through 2011. Trans-Border Institute, San Diego

Cunningham DE, Gleditsch KS, Salehyan I (2009) It takes two: a dyadic analysis of civil war duration and outcome. J Confl Resolut. doi:10.1177/0022002709336458

Dudley S (2011) Zetas-La Linea alliance may alter balance of power in Mexico, http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/zetas-la-linea-alliance-may-alter-balance-of-power-in-mexico

Escalante F (2013) Homicidios 2008–2009: La muerte tiene permiso. Nexos, January 1

Findley M, Rudloff P (2012) Combatant fragmentation and the dynamics of civil wars. Br J Polit Sci 42(04):879–901

Gallagher-Cunningham K (2013) Actor fragmentation and civil war bargaining: how internal divisions generate civil conflict. Am J Polit Sci 57(3):659–672

Gallagher-Cunningham K, Bakke KM, Seymour LJ (2012) Shirts today, skins tomorrow dual contests and the effects of fragmentation in self-determination disputes. J Confl Resolut 56(1):67–93

Grayson GW (2011) Mexico: narco-violence and a failed state? Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick

Guerrero-Gutiérrez E (2012) La estrategia fallida. Nexos, December

Guerrero-Gutiérrez E (2011) Security, drugs, and violence in Mexico: a survey. Lantia Consultores, México

Hernández A (2012) Los señores del narco. Grijalbo, Mexico

Hope A (2014) Las trampas del centralismo. Nexos, July 1

Hope A 2013) Violencia 2007–2011. La tormenta perfecta. Nexos, November 1

Hugh-Jones D (2013) Reputation and cooperation in defense. J Confl Resolut 57(2):327–355

Human Security Report Project Definitions. http://www.hsrgroup.org/our-work/security-stats/Definitions.aspx

InSight Crime (2015a) Familia Michoacana. http://es.insightcrime.org/noticias-sobre-crimen-organizado-en-mexico/familia-michoacana-perfil

InSight Crime (2015b) BLO. http://www.insightcrime.org/mexico-organized-crime-news/beltran-leyva-mexico

InSight Crime (2015c) Cartel del Golfo. http://es.insightcrime.org/noticias-sobre-crimen-organizado-en-mexico/cartel-del-golfo-perfil

InSight Crime (2015d) Caballeros Templarios http://es.insightcrime.org/noticias-sobre-crimen-organizado-en-mexico/caballeros-templarios-perfil

Leeson, P.T. (2006). Cooperation and conflict. Am J Econ Sociol, 65(4), 891–907.

Levy JS (1981) Alliance formation and war behavior: an analysis of the great powers, 1495-1975. J Confl Resolut 25(4):581–613

Merino J (2011) Los operativos conjuntos y la tasa de homicidios: Una medición. Nexos, June 1

Mosso R (2013) Cae Alberto Carrillo, lider del Nuevo Cartel de Juarez. Milenio.com. Retrieved May 13, 2015, from http://www.milenio.com/policia/Alberto-Carrillo-Nuevo-Cartel-Juarez_0_146385597.html

Osorio J (2015) The contagion of drug violence spatiotemporal dynamics of the Mexican war on drugs. J Confl Resolut 59(8):1403–1432

Pearlman W, Gallagher-Cunningham K (2012) Nonstate actors, fragmentation, and conflict processes. J Confl Resolut 56(1):3–15

Phillips B (2015) How does leadership decapitation affect violence? The case of drug trafficking organizations in Mexico. J Polit 77:2

Polo M (1995) Internal cohesion and competition among criminal organizations. Econ Organised Crime, 87–108

Powell B, Stringham EP (2009) Public choice and the economic analysis of anarchy: a survey. Public Choice 140(3–4):503–538

PGR (2013) Células delictivas con presencia en el país. PGR, Mexico

Rios V, Shirk DA (2011) Drug violence in Mexico: Data analysis through 2010. Trans-Border Institute, University of San Diego, https://justiceinmexico.files.wordpress.com/2011/03/2011-tbi-drugviolence.pdf

Rudloff P, Findley MG (2016) The downstream effects of combatant fragmentation on civil war recurrence. J Peace Res 53(1):19–32

Scott WR (2013) Institutions and organizations: ideas, interests, and identities. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Sambanis N (2004) What is civil war? Conceptual and empirical complexities of an operational definition. J Confl Resolut 48(6):814–858

Smith A (1995) Alliance formation and war. Int Stud Q 39(4):405–425

Snyder R, Duran-Martinez A (2009) Does illegality breed violence? Drug trafficking and state-sponsored protection rackets. Crime Law Soc Chang 52(3):253–273

Staniland P (2012) Between a rock and a hard place insurgent fratricide, ethnic defection, and the rise of pro-state paramilitaries. J Confl Resolut 56(1):16–40

Valdés-Castellanos G (2013a) Historia del narcotráfico en México. Aguilar

Valdés-Castellanos G (2013b) El nacimiento de un ejército criminal. Nexos

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Conflict of interest

Author A declares that he/she has no conflict of interest. Author B declares that he/she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not Applicable.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 109 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Atuesta, L.H., Pérez-Dávila, Y.S. Fragmentation and cooperation: the evolution of organized crime in Mexico. Trends Organ Crim 21, 235–261 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-017-9301-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-017-9301-z