Abstract

When Americans are frightened by ethnic or racial polarization, one response is the melting pot, a metaphor for intermarriage. Marriage across ethnic or racial lines turns distrustful groups into contributors to each other’s demographic future. Melting pots have been multiple in American history. While they often have been constrained by racial prejudice, racial intermarriage is now on a slow but steady upswing. Two groups that bear watching are Rednecks, who descend from British migration to what is now the United States, and Norteños, a term I use to refer to Mexican migration streams that, like Rednecks, have become a cultural model for a wider spectrum of Americans. Both Rednecks and Norteños originated as frontier populations in which the struggle for survival selected for self-reliance, distrust of government and the family-first principle. While both are beset by pejorative imagery of machismo, racism and criminality, their strong sense of kinship is a sign that they have more in common than might appear. Just as it is a mistake to reduce all relationships between white and black Americans to racism, it is also a mistake to assume that Norteños and Rednecks are necessarily hostile to each other. Despite the limitations of the melting pot metaphor, it does provide a plausible alternative to racialism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Owing to low American birthrates and high immigration rates, the ethnoracial composition of the United States is changing faster than that of any other large, powerful country. One big issue is jobs—will the U.S. economy generate enough livable wages for all the people who want to come here, let alone all the people we already have? Another issue--how do we persuade Americans to pay high taxes to meet the needs of large numbers of immigrants with whom they fail to perceive anything in common?

How to achieve e pluribus unum—out of many, one—is a perennial issue in American society. For the better part of the twentieth century, the most widely-subscribed answer was the melting pot. Melting pot ideology does not have as large and enthusiastic a fan base as it once did. Nor is it a completely accurate description of how U.S. society has operated in the past or will in the future. But the melting pot does have one shining merit that we can visualize by considering two different groups in U.S. society that make many other Americans nervous. One is Rednecks—a term all Americans recognize--and the other I will call Norteños—a term that requires explanation. Norteños is Spanish for “northeners,” which Mexicans sometimes apply to migrants who go north to the U.S. My question--could there be a Redneck-Norteño melting pot, operating under the radar of academic research and elite commentary, which will produce a new American identity?

How Different Migration Streams Produce the Melting Pot

In the 1970s a German named Werner Sollors arrived on these shores and became an admirer of the melting pot. In the 1980s, as the melting pot was coming under increasing scrutiny, he came to its defense by arguing that it grew out of two conflicting principles in American history. One is descent, which is the principle of who you come from, or at least who you think you come from. If you place lots of emphasis on this principle, it makes you exclusionary toward people with different origins. The other principle is consent, which is how people from different backgrounds come together through trade, citizenship, religion and reproduction. Stressing consent makes you more inclusionary toward people who are different from you.

For anthropologists, descent and consent is the old debate in British social anthropology between descent and alliance. Which is more important in pulling together kinship systems, blood or marriage? Who to include and who to exclude is an unavoidable problem in human affairs. In the United States, as immigrants have shown up from more and more places, descent has long been on the defensive, consent has gained ground, and American society has become more inclusive.

Why would descent ideology lose ground? One obvious reason is capitalism. Even if many Americans would like to be exclusionary, we are so deeply in debt that the only way to keep up with our payments is economic growth. The fastest way to grow an economy is to trade with any willing partner. Not to mention that capitalists have always been in love with the cheapest possible labor. These are two reasons why the big money in American history usually comes down on the side of being inclusionary.

At the start of the twentieth century, according to Sollors, Americans debated three different positions toward immigrants. The first was what he calls Anglo conformism. Anglo conformists wanted everyone in American society to conform to their own White Anglo-Saxon Protestant standards. This did not necessarily mean rejecting immigrants; WASPs could welcome foreigners who accepted their parameters. The welcome often included the production of children with newcomers or their Americanized children. But WASP elites were far from a single ruling class, there were many fissures in their authority, and a growing fraction of Americans—including many younger WASPs--were eager to defy them. This is why, in the 1930s, stuffy WASP patricians became Hollywood’s favorite target. Since then they have lost so many political and cultural battles that, among my students born in the 1990s, some have never heard of WASPs—I have to explain who they were.

The second position toward newcomers, according to Sollors, was cultural pluralism. Cultural pluralists argued that each immigrant group should maintain its culture and identity. They wanted Americans to accept that the U.S. was no longer a single nation; instead, it should become a non-national confederation of nations, in which Greeks would usually marry Greeks, Poles would usually marry Poles, and so on. Only in that way could all the different national and religious groups remain loyal to their traditions. Many first-generation immigrants do wish to maintain their culture of origin, as do some of their descendants, so this position will never lack for adherents. But as an organizing principle, under American conditions, it is too exclusionary to shape social reproduction for more than a generation or two. Usually it is confounded by what we might call the American dance floor—who’s attracted to whom and who gets pregnant by whom, regardless of what elders want.

The third position toward newcomers was the melting pot, according to Sollors, and this is the one that became hegemonic. Nowadays the melting pot is often mistakenly assumed to mean Anglo conformism. But it’s not. The first to come up with the idea may have been a Frenchman, Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, who in 1782 famously argued that, in America, “individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men.” A hundred and thirty years later, the melting pot became a national metaphor thanks to Broadway. The big hit of 1909 was a play in which a Jewish boy from the Lower East Side falls in love with the daughter of a Russian aristocrat. Back in Russia, the girl’s father ordered the pogrom that killed the boy’s father. But the bright promise of the New World allows enemies from the Old World to overcome their differences, by producing a family and the new race of Americans. This is how the British playwright Israel Zangwill, in the title of his play, gave us the melting pot.

The melting pot did not presume that immigrants should remake themselves as White Anglo-Saxon Protestants, Sollors points out. But once Italians and Hungarians were marrying each other, their children would be unable to decide which of their Old World bloodlines should take precedence. They would tire of calculating their fractional ancestries, whereupon they would prioritize their identity as Americans. As more people from more countries became Americans, all these new citizens would shift our definition of what it meant to be American. And so the melting pot was “an imaginative, though immensely pliable, middle ground” (p.74) in which different ethnic groups produced joint offspring who would push American identity in new directions.

To grasp how much American identity has changed over the last two hundred years, consider the historian Michael Lind’s periodization of three successive American nations or republics:

• the lst American nation (1775–1861) he calls Anglo-America. This was the heyday of the WASP but collapsed in the Civil War between North and South.

• the 2nd American nation (1865–1965) was Euro-America, in which white immigrants from other parts of Europe were gradually admitted to equal status. So were Catholics and Jews; Protestants gradually lost their monopoly on political power.

• the 3rd American nation (1965-) is Multicultural America. It began when the U.S. Congress finally got around to legislating equality for black people in the form of the Civil Rights Act. Multicultural America is more inclusive than the two previous American nations, but it is troubled by what Lind calls racial preferences and what I will call racialism. Racialism comes at us from both the right and the left, and it pressures us to attune to our racial identities as whites, blacks, Native Americans, Asians or Latinos. It also pressures us into identity politics, that is prioritizing our identity as victims rather than as members of broader categories such as the citizenry, in ways that contributed to Donald Trump’s narrow victory in the 2016 presidential election.

Could the Melting Pot Become Transracial?

Getting back to the melting pot, it appealed to generations of Americans anxious about national unity. But was it more than an attractive metaphor? If we look at how Israel Zangwill’s play reflected sociological trends, Americans from different national origins were indeed marrying each other. I am the product of back-country New England Yankees marrying Irish- and German-Americans. My home in the Upper Midwest has been a melting pot of WASPs, Germans, Scandinavians, Poles and Dutch.

Melting was not confined to migration streams from Europe. The majority of Native Americans descend from intermarriage between different eighteenth- and nineteenth- century tribes. New York City became a melting pot of black Americans from the North, black Americans from the South, and immigrants from the Caribbean and West Africa. New York City also has been a melting pot of Puerto Ricans and Dominicans. The Guatemalan immigrants with whom I do research are joining a Mexican and Central American melting pot.

What are the actual rates of intermarriage between different national groups? I don’t have figures and, as far as I know, they do not exist. The Pew Research Center quantifies intermarriage but unfortunately not between nationalities. Instead, Pew is tracking intermarriage between racial groups as we currently define them. Our current racial pantheon is whites, blacks, Native Americans, Asian-Americans and Latinos—even though Latinos are not a racial group because Latin Americans include members of all racial groups.

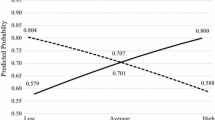

According to Pew’s analysis of U.S. Census data (Livingston and Brown 2017), the rate of racial intermarriage has increased five-fold from 1967 to 2015—but to only 17% of all new marriages. Doing the best job of marrying outside their own group are Hispanics at 27% and Asians at 29%.; for U.S.-born Hispanics the figure rises to 39% and for U.S.-born Asians to 46%. Far and away the most common kind of intermarriage is what Pew calls White/Hispanic (42%)—but since many Hispanics define themselves as white, many of these couples may not define themselves as inter-racial. Majorities of people in each racial classification are not marrying outside their racial classification: 82% of blacks are marrying other blacks and 89% of whites are marrying other whites.

So while racial intermarriage is increasing in American society, it is not galloping forward. Nor is it happening very often across what still seems to be U.S. society’s deepest cleavage, the white/black color line. Barriers to white/black intermarriage have long been the most obvious refutation of melting pot ideology. For a hundred years after the Civil War, black Americans who tried to melt with white Americans were often punished for it. As many as thirty states had laws against it. 1 Even now white/black parents and their children may encounter discrimination. And so contemporary race and ethnicity scholars have an understandable reason to dismiss the melting pot, as an ideology that obfuscates racism.

Even Michael Lind has gotten discouraged about our ability to melt together through intermarriage. In his 1996 opus The Next American Nation, Lind urged us to push onward to a 4th American nation, the Trans-Racial Melting Pot. If you really want to do something for your country, Lind proposed, marry somebody from another racial group and have children together. He hoped that more intermarriage would overcome the racialism of our current Multicultural America.

More recently, Lind seems to have given up these hopes. In 2013 he concluded that white Southerners so opposed the melting pot that they rejected intermarriage even with European immigrants. Nowadays, he argues, Southern support for reactionary policies has become a last-ditch defense of racial supremacy, against a demographic future in which non-Hispanic whites will become a racial minority even in the South.

Rednecks as a Frontier Population

According to Pew researchers, an increasing percentage of Americans say they accept racial inter-marriage, but Republicans lag Democrats in this regard, as do the less educated and the more rural. Of all white people whom we could presume to continue opposing inter-racial marriage, who are more likely candidates than Rednecks? In the liberal enclave where I live, we don’t talk a lot about Rednecks. When they do come up, we associate them with ignorance, prejudice, and ownership of excessive numbers of firearms. But no one in a liberal enclave wants to be prejudiced, so let’s take a closer look.

The historian David Hackett Fischer has documented four very different migration streams from Britain into the thirteen colonies:

• the Puritans of New England,

• the Quakers of Pennsylvania,

• the Anglicans and Catholics of the Tidewater South, and.

• the Scots-Irish who settled the frontiers, then the Appalachians, and gave birth to the American Redneck.

We might think that a pejorative like Redneck, as well as its close cousin the cracker, are American slang, but according to Fischer both terms go back to Britain, to the violent border between England and Scotland. The bulk of the border population were tenant farmers and herders on large estates, so they were subordinate to lords in ways which defined them as peasants. But many were also junior blood relatives of those same lords, in ways which defined them as clansmen.

Fischer refers to these people as borderers. He adds that they enjoyed an unusual level of independence because their lords, English to the south and Scots to the north, needed them to fight their wars with each other. So Rednecks and crackers are descended from the north Briton border wars, which schooled them in the manly arts of rustling cattle, stealing women, and waging vendettas. Then, after the English and Scottish crowns united in 1603, border warfare diminished. Over the next 150 years, the lords needed fewer and fewer fighting men. They also discovered that their tenants were less profitable than sheep.

What to do with surplus fighters? Why not ship them across the Irish Sea to Ulster? And so borderers were transplanted to northern Ireland, where they helped subjugate the native Irish population. During this same period, our future Scots-Irish were becoming Calvinists, which would reverberate for centuries in grudge matches between Ulster Protestants and Catholics. But northern Ireland was not their final destination. Owing to deep grievances against their English employers, some Scots-Irish kept going across the Atlantic, all the way to colonial seaports such as Philadelphia and Newcastle. Hungry for land, they moved out to the frontiers of the Thirteen Colonies, from the Hampshire Grants and Pennsylvania to the Cumberland Gap, Virginia and the Carolinas. Following independence from Britain, in the nineteenth Century the Scots-Irish provided many of the frontiersmen, soldiers and settlers who pushed the American republic south to the Rio Grande and west to the Pacific.

Since Rednecks are a stereotype, let’s excavate three different layers in the imagery about them:

1) in our current social imagination, Rednecks are trash-talking lower-class rebels who are gonna whup your ass. J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, about his ne’er-do-well Scots-Irish relatives in Kentucky and Ohio, chronicles their capacity for self-destruction. Why this reputation for misdirected anger? One reason is that, while Americans like to believe the U.S. frontier was full of opportunity for everyone, in actuality even the Scots-Irish were divided into social classes with very different levels of access to land titles. Thus Scots-Irish settlers were at high risk of of losing their land to speculators and lawyers, turning them into squatters and outlaws even as they fiercely claimed to be the equal of any man. So a history of egalitarianism and disenfranchisement, going all the way back to northern Britain, helps explain the profanity and defiance that we associate with Rednecks.

Another reason why Rednecks act like Rednecks dates back to the clan organization of the north Briton borderers. In contrast to the increasingly policed south of Britain, their organizing principle was still kinship—my family right or wrong. Hence the Hatfield-McCoy feud in Kentucky. Outsiders were viewed with deep suspicion, from which we get the pejorative imagery of hillbillies holed up in mountain hollows, breeding with their cousins and threatening interlopers with shotguns.

2) On a second level, however, Scots-Irish settlers did not consist solely of a “backcountry underclass” (Fischer 1989:756) because they also built the first Anglo power structures in the Appalachians, the Upper South, the southern Midwest and west to Texas. Assisting in this regard were their religious exertions, producing churches which toned down the unruliness and tamed some of the patriarchy. There was also lots of intermarriage with other ethnic groups—particularly Germans, French Huguenots and Louisiana Cajuns. This second level produced Rednecks who still had the ability to act Redneck when they wanted, but who were often more interested in acquiring respectability.

3) Finally, at the level of popular culture, Redneck imagery proved to have enormous appeal beyond Scots-Irish descent. Cowboys, country-western musicians, and long-haul truck drivers are fond of claiming Redneck status, as are certain kinds of Christians, much of the armed forces, and a substantial fraction of red-state America. What percentage of the U.S. population will, on occasion, proudly claim to be Rednecks? So at this third level, a term which began as a pejorative has become a source of pride for large numbers of Americans. Rednecks have become an expansive, easy-to-join category in American culture. The only requirement is to be able to act like one, hopefully without provoking arrest by the nearest deputy sheriff.

What American elites think of Rednecks has always been heavily dependent on context. If you want to grab or defend territory, lower-class males with a capacity for belligerence are essential. But these same lower-class males often have too much attitude to become model workers at a later stage of capitalist development. At this point, the standard upper-class move is to replace their own lower class with more pliable workers from elsewhere.

Thus some of the first European explorers in the New World predicted that, in contrast to the lower-class European scoundrels manning their expeditions, Native Americans would make ideal Christians and laborers. When that didn’t pan out, who were the next ideal workers? Slaves from Africa. When the North abolished slavery after the Civil War, who did northern industrialists recruit for their factories? Not black people—they were getting uppity. And so industrialists recruited immigrants from southern and eastern Europe.

Norteños as a Frontier Population

Meanwhile, Anglo businessmen in the southwestern states began to draw on a new source of ideal workers—the inhabitants of northern Mexico. How we should denominate them is a challenge—Mexicans is the usual term in the U.S., but Mexico is inhabited by many different peoples and the border historian Juan Mora Torres argues that this particular kind of Mexican has been systematically ignored by Mexican historians. I will call them Norteños because this is a term Mexicans apply to people who go north to work. They can also be called fronterizos or frontier-dwellers, and culturally they descend from the soldiers, mule-skinners and artisans of Spanish expansion out of central Mexico.

How did Norteños and their milieu compare with the U.S. western frontier? The Mexican northern frontier was a slower process; it began in the 1500s and went on for three centuries before Anglo-Americans arrived. Another difference is that Catholic missions played a central role in sedentarizing the indigenous population. A third is that Spanish-speakers produced more offspring with indigenous people than English-speakers did. These are important differences but, since both frontiers represented European expansion, parallels are also strong.

Both Mexicans and Americans were seizing territory from indigenous groups, which meant periodic warfare of great brutality. One was a hispanizing frontier just as the other was an anglicizing frontier; many indigenous parents decided to raise their children in Spanish rather than their own language, such that the majority of the population came to identify with the new colonial order. Both sets of expansionists were moving into arid interiors where the only way to survive was through small-scale farming, grazing and mining. Last but not least, because Spanish-speakers arrived much earlier, the English-speaking Americans who began to reach Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California in the 1820s learned a lot from them. For example, the leathery kit that we associate with American cowboys descends from Mexican cattlemen.

A comprehensive social history of nineteenth Century Mexican frontier-dwellers I have yet to find. Many scholars swing near the subject only to then focus on political history or the injustice of the U.S. border. The usual impression of nineteenth Century rural Mexicans is that they were under the heel of hacienda owners and Catholic priests, that politics was monopolized by feuding elites, and that it was the deep subordination of most of the population, their lack of literacy and engagement with the state, that made Mexico so vulnerable to civil wars. So the Mexican frontier sounds far less egalitarian than the U.S. frontier. But I wonder if this is an accurate description of Mexican frontier-dwellers; it doesn’t seem to explain the initiative required to survive Indian attacks and join rebellions. What might best capture their spirit is Américo Paredes’ (1958) chronicle of Gregorio Cortéz, an early twentieth Century Tejano who became legendary for standing up to abusive Anglo law enforcement.

Between 1836 and 1848, Mexico’s northern frontier was truncated by a new border with the United States. Spanish-speakers were caught between the grinding stones of Mexican and American authoritiy, neither of which was a reliable guarantor of their property and lives. Henceforth significant numbers of Spanish-speakers—the Tejanos of Texas, the Hispanos of New Mexico, the Sonorans of Arizona and the Californios of Southern California --were on the U.S. side of the border. Moving north across that border were growing numbers of other Mexicans, some driven out by political upheavals and others attracted by higher wages.

Because I need an umbrella term, I will lump together these differing groups and call them Norteños. As Norteños became the workforce of Anglo ranchers, growers and miners, they became a social and cultural template for labor migrants from further south in Mexico, and more recently for Guatemalans and other Central Americans. As Norteños carved out occupational niches for themselves, they moved beyond agropastoral labor. While they were very subordinate in some ways--including mass deportations when their labor wasn’t needed--some acquired significant mobility, both to other parts of the U.S. and also back and forth to their hometowns in Mexico. Some returned south to become local leaders of the Mexican agrarian reform of the 1930s (Mora Torres 2014). Others stayed in the U.S. and moved into better-paying sectors such as labor contracting and construction.

One obvious difference between Rednecks and Norteños is that, at least as they are stereotyped in the news media and popular culture, Rednecks are a lot less subordinate. When Rednecks are acting like Rednecks, they are playing up their lower-class status but also demanding to be lords unto themselves. In contrast, with certain exceptions such as early twentieth Century Tejano secessionists and more recent Aztlán advocates, Norteños in the U.S. are not known for demanding sovereignty.

Still, there are important parallels between Norteños and Rednecks. Both originated as what Américo Paredes and David Hacket Fischer call borderers. Their progenitors were shaped by harsh frontier environments which demanded the ability to improvise and to defend yourself. Rednecks provided lower-class muscle for U.S. territorial expansion. Their conquests seemed to halt the Mexican fronterizos who were pushing north, by creating a border which turned many fronterizos into disenfranched minorities. Yet the U.S. border did not stop fronterizos from becoming Norteños who have, through labor migration, spread throughout the U.S. and become a growing fraction of the population.

Equally important, Norteños have, like Rednecks, become cultural templates for people who came after them. Just as we see much admiration for Redneck culture, there’s much admiration for Norteño culture. Think of the popularity of Country Western and Norteño ballads with their shared themes of bravado, rebellion, and romantic loss. Think of the anguished debate in Mexico over narco-corridos, the ballads that celebrate druglords and their slaughter of anybody who gets in their way (Schwarz 2013).

What exactly is so admirable about Norteños and Rednecks? One trait that Norteño and Redneck men share, at least stereotypically, is an exaggerated masculinity which is easy to romanticize and easy to condemn. If we avoid such temptations, stereotypical Norteño/Redneck masculinity looks like a response to being recruited for warfare and other roughneck occupations, to being manipulated by elites, and to becoming culturally habituated to a lack of reliable state authority. In any case, both Rednecks and Nortenños cultivate distrust of government and pride in self-reliance.

For the same historical reasons, both Norteños and Rednecks exemplify the family-first principle: if protecting their family requires breaking the law, they are not apologetic. For both groups, family-first can extend beyond parents, mates and children because, on bygone frontiers and often still today, cousinhood is the basis for organizing economic and political life. On a frontier, people have to scatter across the landscape to support themselves, but they must stay within range of mutual aid to deal with emergencies. Under pressure from hostile forces, moreover, Rednecks and Norteños would extend the kinship principle to anybody who was willing to reciprocate--not just blood relatives and in-laws but supportive neighbors. It’s this tradition of mutual aid that enables Redneck and Norteño kin networks to turn into neighborhood defense groups, or militias that march off to war, or criminal enterprises.

From the Jesse James Gang to moonshiners, the Ku Klux Klan and anti-government militias, Rednecks have long been credited with a talent for criminal combination. As for Norteños, some have spent generations honing their skills in evading U.S. border enforcement. Recently the customers of Norteño smugglers have included hundreds of thousands of Guatemalans from the region where I do research as an anthropologist. Let’s not forget so-called Mexican drug cartels which are less cartels than crime families along the lines of Sicilian mafias. Where kinship-based drug organizations are most powerful is south of the US-Mexican border; how powerful they are north of the border is much debated.

Rednecks and Norteños as Two Competing Melting Pots—Will They Come Together by Producing Children?

So we have several important resemblances between Norteños and Rednecks. Both have frontier origins that are easy to mythologize, and both promote a certain kind of masculinity that is easier to admire from a distance than to live with, especially if you’re a woman. In my closing pitch for Norteños and Rednecks, I’m going to argue that they share a masculinity that can be tamed, usually by a combination of womenfolk, employment and godliness. Because this kind of masculinity produces families, let’s circle back to the melting pot and Michael Lind’s “next American nation.”

The weakness of melting-pot ideology is that it’s a feel-good nation-building metaphor that may not reflect reality. I don’t have data on current rates of intermarriage between Mexican-Americans and the kinds of Americans who identify themselves as Rednecks. My hunch is that they are more attractive to each other, and producing more children together, than we might think from all the pejorative imagery about racism and criminality. Just as it would be a mistake to reduce everything that happens between white and black people in the U.S. to racism, it’s a mistake to assume that Norteños and Rednecks are necessarily hostile to each other. They have too much in common for this to always be true.

If you don’t like the melting pot metaphor, call it the middle ground (per the historian Richard White’s portrayal of the Old Northwest Frontier) or mestizaje (as we do in Latin American studies). Whatever you call it, we’re looking at an age-old phenomenon that brings together people of different backgrounds. That phenomenon is sex, what sex produces is babies, and what babies produce is kinship—if there is enough family structure for both families to claim the baby as their own. How much family structure will survive our current state of demoralization is an important question. Despite that caveat, children are the fastest way to turn a different ethnic group into a contributor to the future of your own ethnic group. When those children grow into adults, their ethnic loyalties are likely to be divided or diluted.

With whom you have sex and babies, and with whom you form households, is an important contributor to inclusion but not the only one. Another contributor is the work people do, that puts them into long-term cooperative relationships with people from other groups. Most Rednecks and Norteños are going to be in the working class for the forseeable future. Another contributor to inclusion are churches, which operate on kinship metaphors that also pull together people from different backgrounds. Born-again Protestant churches are booming among Latino immigrants--this is another way Norteños and Rednecks are coming into contact with each other.

However flawed the melting pot metaphor, it does provide a plausible alternative to racialism. Racialism doesn’t necessarily add up to racism—it’s merely the insistence that individuals and groups should understand their past and future in terms of their racial identity. The great virtue of intermarriage is that it takes advantage of a very basic impulse that runs counter to racialism, by producing offspring who confound the categories into which they were born.

Notes

Further Reading

Fischer, D. H. 1989. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. New York:Oxford University Press.

Lind, M. 1996. The Next American Nation: The New Nationalism and the Fourth American Revolution. New York:Free Press.

Lind, Michael. 2013 “The white South’s last defeat: Hysteria, aggression and gerrymandering are a fading demographic’s last hope to maintain political control.” Salon, February 5.

Livingston, Gretchen and Anna Brown. 2017. Intermarriage in the U.S. 50 Years After Loving v. Virginia. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, May 18.

Paredes, A. 1958. With His Pistol in his Hand. In A Border Ballad and its Hero. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Schwarz, Shaul. 2013. “Narco Cultura,” film documentary.

Sollors, W. 1986. Beyond Ethnicity: Consent and Descent in American Culture. New York:Oxford University Press.

Torres, J. M. 2001. The Making of the Mexican Border. Austin:University of Texas Press.

Torres, J. M. 2014. “Los Norteños in Mexican History — from 1900 to the current Great Eviction,” April 2, El BeiSMan (http://www.elbeisman.com).

Vance, J. D. 2016. Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. New York:HarperCollins.

Webb, J. 2004. Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America. New York:Broadway Books.

White, R. 1991. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stoll, D. Rednecks, Norteños, and the Next American Melting Pot?. Soc 55, 11–17 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-017-0205-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-017-0205-y