Abstract

Contemporary trends in low fertility can in part be explained by increasing incentives to invest in offspring’s embodied capital over offspring quantity in environments where education is a salient source of social mobility. However, studies on this subject have often neglected to empirically examine heterogeneity, missing out on the opportunity to investigate how this relationship is impacted when individuals are excluded from meaningful participation in economic spheres. Using General Social Survey data from the United States, I examine changes in the relationship between number of siblings and college attendance for White and Black respondents throughout the 1900s. Results show that in the early 1900s, White individuals from larger families had a lower chance of completing four years of college education than those from smaller families, whereas the likelihood for Black individuals was more uniform across family sizes. These racial differences mostly converged in the later part of the century. These results may help explain variations in the timing of demographic transitions within different racial groups in the United States and suggest that the benefits of decreasing family size on educational outcomes may be conditional on the specific economic opportunities afforded to a family.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Because resource availability limits reproduction, we should expect to find a positive relationship between access to resources and number of surviving offspring across various species. This relationship is evident in both historical human societies (Clark & Hamilton, 2006; Nettle & Pollet, 2008) and nonhuman primates (Harcourt, 1987), indicating its relevance in past human evolution. However, cross-country analyses of fertility reveal an inverse association with wealth than what is expected (Vandenbroucke, 2016), and in contemporary America, the relationship between wealth and individual fertility depends on one’s gender and income strata (Hopcroft, 2019; Stulp et al., 2016). These findings seem contradictory to evolutionary logic, calling for a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms driving human reproductive behavior.

Some studies on fertility have employed the concept of the quantity–quality trade-off, proposing that reduced fertility optimizes long-term fitness by prioritizing the reproductive success of one’s offspring over one’s own (Lack, 1947; Lawson and Borgerhoff Mulder, 2016). Although such a trade-off has indeed been observed in various studies comparing human fertility with offspring health outcomes (Meij et al., 2009; Hagen et al., 2006) as well as measures of social success (Anh et al., 1998; Eloundou-Enyegue & Williams, 2006; Goodman et al., 2012; Kaplan et al., 1995; Van Bavel, 2006), the idea that gains in offspring quality can increase fitness through the improved reproductive success of subsequent generations fails to be supported by analyses of fertility in populations characterized by low child mortality (Goodman et al., 2012; Kaplan et al., 1995). In response to the incongruity between observed fertility rates and expected optimums for fitness maximization, others have suggested that human reproductive behavior is probably influenced by evolved psychological mechanisms that are sensitive to traits that served as proxies of fitness in the past but have maladaptive outcomes in novel environments (Kaplan et al., 1995). The close relationship between status, resources, and fitness recognized in past human societies and other primate species (Majolo et al., 2012; von Rueden & Jaeggi, 2016) suggests that humans may have evolved to be sensitive to opportunities to optimize status, rather than overall fitness (Alvergne & Lummaa, 2014; Borgerhoff Mulder, 1998; Shenk et al., 2016). Therefore, fertility should be reduced if having additional offspring significantly impedes the parents’ ability to improve their existing offspring’s status.

Understanding how parental investments are converted into status may be the key to making sense of the observed decrease in fertility in postindustrial environments. “Embodied capital” refers to the attributes inherent in an individual’s body that can be converted, alone or with other forms of capital, into assets that improve their fitness (Kaplan et al., 1995). The efficacy of different types of embodied capital in generating resources and status depends on the society’s subsistence style and cultural norms. In some small-scale, traditional subsistence societies, status may “be achieved primarily on the basis of an individual’s activities during their lifetime” (Shenk et al., 2016:2)—for example, by achieving prestige among their peers through displays of skill or good character. In such cases, parents can help their children by teaching them necessary skills or advocating for them in social situations, such as among the Martu, where the presence of a boy’s father can accelerate his initiation into adulthood (Scelza, 2010). Holding aside the baseline resources needed to feed or clothe children, these additional investments are not characterized by being zero-sum; a parent can teach foraging skills to multiple children at the same time or advocate for one child without necessarily taking anything away from another. Moreover, some of these benefits can also be provided by older siblings or community members, further diminishing the demand on parental resources. Because these types of investments are not intrinsically depletable, we should predict fewer incentives to restrict fertility. In contrast, in postindustrialized societies, status is often determined by access to high-income careers, and the value of parental wealth in affecting this—specifically through investment in formal education—is high. Because material wealth is a zero-sum resource, parents must make decisions about the amount they allocate to each child and should be motivated to restrict fertility so that existing children receive sufficient investments. This idea has been proposed to explain the close association among market integration, education, and fertility decline (Colleran & Snopkowski, 2018; Lesthaeghe & Wilson, 1986).

Although this model of fertility variation fits well with the observed patterns of fertility decline that follow industrialization, many studies have been unclear about why, within a population, we should see fertility decline first in wealthy families (Vining, 1986). Why should some families be more motivated to reduce their fertility than others? In the following section, I review how disproportionate distributions of economic opportunities within societies contribute to individual variations in fertility trade-offs.

Structural Explanations for Intragroup Variations in Fertility

Populations are not uniform. Levels of inequality, degree of access to market economies, and the positioning of one’s social or ethnic group within the society can all have important effects on how social mobility opportunities are distributed, and therefore an individual’s ability to convert parental investment into status gains (Alvernge and Lummaa, 2014; Andrews & Leigh, 2009; Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004). Although reducing family size seems beneficial for offspring’s status where parental investment matters, it is reasonable to expect that the efficacy of this strategy is most pronounced within subgroups that have superior access to such status-enhancing opportunities.

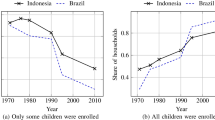

Geographic variations play an important role in determining an individual’s access to market economies and the resulting income opportunities. The initial concentration of development in urban centers, for instance, implies that families residing in proximity to these centers are the first to gain access to high-income labor markets. This phenomenon is evident in Mongolia, where the wealth payoffs for women choosing education over reproduction are more substantial in urban areas, potentially explaining the lower fertility rates in Mongolian cities (Alvergne & Lummaa, 2014). Similarly, an individual’s incentive to invest in their children’s education should be greater where the relationship between education and wealth is stronger. Maralani (2008) shows that in urban regions of Indonesia, the correlation between sibship size and an individual’s total years of education transitioned from positive to negative over a 30-year period corresponding to socioeconomic development. That this relationship is concentrated in urban areas but not rural areas suggests that dynamics in family resource allocation may depend on geographic access to education and labor market opportunities.

On a similar note, regional levels of income inequality can restrict opportunities for economic mobility (Andrews & Leigh, 2009; Shenk et al., 2016). This may be because high levels of inequality lead to social segregation by income, wherein affluent families have better access to educational and social advantages, while low-income families do not, and may also be exposed to higher concentrations of adverse peer effects (Burtless and Jencks, 2003; Durkee et al., 2019; Durlauf, 1996). Supporting this, research indicates that the socioeconomic benefits of fertility limitation are most significant among individuals who are already in high socioeconomic positions (Goodman et al., 2012), and wealthier parents report greater fertility–investment trade-offs in large family sizes than their less affluent counterparts do (Lawson & Mace, 2009, 2010). This insight may explain why cross-country analyses reveal that the fertility difference between more- and less-educated individuals is more pronounced in countries with higher inequality (Kremer & Chen, 2002).

Lastly, variations in the scope of influence that parents can have on their offspring’s status can arise when societies are stratified by ethnic or cultural subgroups. In such cases, a person’s identity, as determined by certain cultural or phenotypic markers, can affect if and how a person can change their status. For example, caste systems can limit social mobility by tethering aspects of status to one’s birth family characteristics. The impact of caste systems is exemplified by the fertility paradox observed in Kerala, India, where the significance of rigid caste distinctions was reduced by social reforms in the 1900s, resulting in dramatic national fertility decline, especially in the lower classes. The reduction of fertility has been attributed to the increased ability for individuals to improve their own socioeconomic positioning, therefore increasing the incentives of parents from lower castes to invest more in the education and later-life outcomes of their children (Pallikadavath & Wilson, 2005). Similar constraints to social mobility can be observed in multiethnic societies, where distinct ethnic or racial groups occupy different strata of social status, and these norms are enforced by discriminatory behaviors. Kaplan et al. (1995) observe that in New Mexico in the 1900s, Hispanic men had higher fertility than non-Hispanic White men. They propose that non-Hispanic White men have greater incentives to reduce their fertility because they have greater potential to supplement investments in their children’s education owing to their likely educational background. However, this explanation assumes that Hispanic men with similar income and educational backgrounds to their White counterparts should be equally capable of influencing their offspring’s status. We must also consider that, holding all other factors constant, individuals presenting as members of minority groups may still encounter structural barriers to social mobility that others do not. A racialized social structure may create differences in reproductive patterns by disrupting the link between education and status for racialized groups. To further investigate the effect of racial stratification on reproductive strategies, I evaluate how racial segregation in the United States affected variations in the trade-offs between fertility and education across the 1900s.

Ecologies of Opportunity in the United States

The United States underwent great social and economic change during the 1900s. The start of the century saw the effects of the growing industrial economy. One of the outcomes was that companies and factories needed to fill administrative and management roles, increasing demand for educated workers, and, consequently, individual incentives to invest in higher education (Goldin & Katz, 1999). However, Black Americans and other minorities did not have equal access to the newly created spheres of opportunity that came with industrialization. Although the Thirteenth Amendment had officially abolished slavery in the United States, discriminatory laws and practices continued to restrict social mobility opportunities for Black people. For example, under segregation laws, Black communities were able to create their own schools and colleges, but they often received less funding and could not accommodate everyone who applied (Haynes, 2006). By limiting access to educational institutions and economic opportunities, these practices had important effects on the expected pathway between parental investment and child status.

Although the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination based on color, race, religion, or sex, legally ending Jim Crow and other discriminatory laws, loopholes to this rule continued to advantage White people in many socioeconomic spheres, a legacy that can still be observed in the present day. The income gap between White and Black individuals remains large, as do differences in employment, education, and health (Harris, 2022). Strategic drawing of district boundaries and informal exclusion of housing in White neighborhoods prevent Black people from accessing high-quality public schools, which hampers their access to higher education (Gilbert et al., 2022). Moreover, individuals who do overcome educational barriers still face biases in hiring (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004), which, in combination with other potential workplace inequalities, possibly devalues the monetary benefits of higher education (Table 1). These barriers to economic success are external to the influence of parental investment on children’s later life status. Consequently, I predict: (1) A weaker relationship between family size and educational attainment for Black respondents relative to White respondents. (2) This difference will diminish over time with reduced tolerance for racial discrimination in education and employment.

Methods

Data

I use data from the General Social Survey collected by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC, 2022). Data collection for this project started in 1972 and is ongoing, with new samples added every 1–2 years. The most recent year of data collection was 2022. In each year of data collection, a new sample of up to a few thousand adult participants is recruited through a process that aims to randomly select individuals across the United States from a mix of geographic areas and community types. Participation in the study is voluntary and consists of a 90-minute in-person interview conducted by researchers from the University of Chicago. Interviewers ask respondents about the demographic and economic conditions of their families and themselves, as well as various questions about health and behavior. The entire database comprises 72,390 individuals. For this study I used data from 50,259 individuals sampled between 1972 and 2021. Individuals were selected to be included in this study based on being older than 25, and the availability of the variables of interest described below.

Variables

Offspring education is my outcome of interest. I coded this as a binary variable, differentiating between individuals who did or did not complete four years of college. The data are derived from the interview questions: “Did you complete one or more years of college for credit—not including schooling such as business college, technical or vocational school? IF YES: How many years did you complete?” (NORC, 2022). I chose four years of college to represent those who have completed the standard number of years to receive a bachelor’s degree. I only include individuals aged 25 and older to exclude those that may still be in the process of schooling, assuming a semi-direct pathway from high school to college.

Sibship size is represented through the respondents’ self-reported number of siblings. The survey question associated with this variable is “How many brothers and sisters did you have? Please count those born alive, but no longer living, as well as those alive now. Also include stepbrothers and stepsisters, and children adopted by your parents” (NORC, 2022). This self-reported measure of sibship size provides a proxy measure for trade-offs in parental investment relevant to the respondent’s childhood and education.

Parental socioeconomic status is measured by a self-reported variable of childhood family income. Interviewees were asked: “Thinking about the time when you were 16 years old, compared with American families in general then, would you say your family income was—far below average, below average, average, above average, or far above average?” (NORC, 2022). Because the question asks respondents to reflect on their family income during their teenage years, this variable provides a proxy for the resources available to the respondent during key educational years, and in some cases signifies the amount of family resources available to invest in education after high school.

Region is reported by the interviewer and represents the regions of the United States categorized by the US census. Birth cohort is calculated by subtracting the respondent’s reported age at the time of survey from the survey year, which are both variables reported by the GSS. Individuals are grouped by birth year into 9 cohorts, each spanning a decade. The first cohort is born between 1905 and 1915 and the last is born between 1986 and 1995. Because I use only individuals who reported an age of at least 25 at the time of sampling, individuals sampled by the GSS between 18 and 24 years old (N = 5,696) are excluded from the sample.

Sex and Race identities are reported by the respondent. In this model, I use only White (1) and Black (2) racial groups because in early samples, the GSS represented race as White, Black, or other. I exclude those in the “other” category (N = 4,518) because the nature of this study requires understanding the effect of specific racialized experiences, which cannot be generalized for a category of “other.”

I restricted my sample only to individuals who had complete answers for each of the above variables (N = 50,259). After excluding respondents who were too young or reported a race other than Black or White, parental income was the most missed variable among respondents (N = 10,766). Adjusting for the size of each group, I found no systematic differences in the missingness of parental income values by race, sibship size, or education level, although the proportion of missing parental income values did differ between cohorts. After excluding participants with missing parental income values, other missing variables (sibship size and education) represented less than 2% of the remaining missing data. Therefore, the effect of excluding missing data should have notable consequences only on the number of available samples for each cohort.

Statistical Analysis

To compare historical changes in the relationship between sibship size (main effect) and the probability of having four years of college education for both White and Black groups (interaction effect), I ran the data for each cohort (N = 9) through a multivariate Bayesian logistic regression model. I included sex, region, and childhood family income as control variables. Varying intercepts were estimated for race, sex, region, and childhood family income. Measures of sibship size were standardized by subtracting from each value the population average and then dividing by the sample’s standard deviation. The standardized values were calculated prior to splitting the sample by cohort, and therefore represent data scaled to the entire dataset rather than individual cohorts. The models were fitted in R using the “rethinking” package (McElreath, 2021). Models were run with 4 chains, 4 cores, and 2,000 iterations. The corresponding mathematical equation for the model is.

Results

Aggregating across all cohorts, four years of college was the second most commonly reported level of completed education (26.1%), following a high school diploma. Figure 1 compares rates of college completion between my sample and the US census. My data agree with the general upward trend in college completion as reported by the census. However, yearly rates of college completion from my sample were more variable and on average higher than values reported by the US census, especially for Black populations. Moreover, the difference in college attendance between Black and White respondents was less dramatic in the GSS and disappeared completely in 2020. Comparing the two data sets reveals a bias toward educated individuals in the GSS sampling process. A plausible explanation for this bias is that GSS interview processes require more commitment than the census survey, and individuals with higher education may be more likely to agree to participate in GSS research due to having more free time. This explanation may be especially relevant for the 2020 survey year, where economic and health disruptions from COVID-19 were felt most by those in lower-income sectors of employment (Piacentini et al., 2022). The following results should therefore be interpreted with the understanding that my sample is more educated than average, especially for later cohorts.

Cohort and Parental Income Were Consistently Associated with Education

Across cohorts, I find that the percentage of respondents that have a college degree increased over time for both Black and White cohorts except for between cohorts 5 and 6, where it decreased for both groups (Table 2). Card and Lemieux (2000) also find that college attendance drops for the baby boom generation and propose that this trend can be explained by a combination of low returns to education and the overcrowding of educational institutions during this period. Regardless, the odds of completing four years of college education by age 25 were consistently related to parental income for all cohorts. The largest change in odds was between those reporting lower than average parental income and those reporting average income (Fig. 2). This finding is in line with expectations that wealthier families are more likely to have the ability to invest in the education of their children (Goodman et al., 2012).

Posterior densities illustrate the difference in probabilities of completing 4 years of college between those reporting lower than average family income in childhood and those reporting average or higher family income. The central x = 0 line here represents no difference; values to the right of this line represent a greater positive effect for average and high-income groups. Annotations show the percent of β values that are greater than 0; *** 90% β > 0. Made in R

The Relationship between Sibship Size and Education Differed by Race

Overall, respondents had a mean of 3.8 siblings, with the maximum number of siblings being 37, as reported by one respondent. In my sample 5.1% of all respondents reported having no siblings and 36.4% of respondents reported having only 1 or 2 siblings. Black groups had higher average sibship sizes than White groups in all cohorts, and there was an overall decrease in sibship size across birth cohorts for both groups, although for Black groups, this seems only to appear after cohort 6 (Table 2; Fig. 3). Number of siblings had a negative effect on one’s chances of completing four years of college for all race and cohort groups, though this effect was only significant in some groupings (Fig. 4). This finding is in line with other studies that have found a negative relationship between number of siblings and educational attainment (Anh et al., 1998; Eloundou-Enyegue & Williams, 2006; Goodman et al., 2012; Kaplan et al., 1995). In support of my first prediction, the negative relationship between sibship size and education was greater for White people than for Black people in cohorts 1 through 6. This is best demonstrated in individuals born between 1916 and 1925, where one additional standard deviation in sibship size had an average 83% negative effect on the odds of completing four years of college for White individuals, but only an average 18% negative effect for Black individuals (Fig. 4).

Posterior densities of the interaction effect of race and sibship size on education. Left: Black line is rendered by subtracting Black posterior densities from White posterior densities, depicting the difference in effect of sibship size on education between the two groups for each cohort. The central x = 0 line here represents no difference between Black and White groups; values to the left of this line represent a greater negative effect in White groups than in Black groups. Right: Red line depicts densities for Black groups only, and blue line depicts densities for White groups only. The central line on x = 0 represents no effect of sibship size on education; values to the left of this line represent negative effects. Annotations show the mean β and the percent of β values that are less than 0: * 70% β < 0. ** 80% β < 0. *** 90% β < 0. Made in R

Racial Differences in the Sibship–Education Relationship Converged with Time

My second prediction that the relationship between sibship size and education would converge for Black and White people over time was also seen in the data. In contrast to early cohorts, the effect of sibship size on college attendance was identical for Black and White individuals born between 1956 and 1965. Moreover, in subsequent birth cohorts, the negative effect of having additional siblings is slightly greater for Black individuals (Fig. 4). The same pattern is demonstrated in Fig. 5, which depicts the estimated probabilities of college attendance derived by running simulated data through the trained models. The use of counterfactual data illustrates how the relationship between education and sibship size changes across time. In the first cohort all individuals regardless of parental income or sibship size had low probabilities of college attendance. Subsequently, White individuals from smaller families were the first group to increase their attendance rates, and this small family advantage remains even after overall college attendance for all White families increased in later cohorts. In contrast, in the first three cohorts, the probability of college attendance remains low for Black individuals of all sibship sizes, but as the probability of attending college increases for Black groups in later cohorts, the difference in probabilities for small and large sibship sizes is minimal. It isn’t until cohort 5 that the relationship between education and sibship size for Black groups begins to steepen, causing the relationships for both White and Black groups to almost mirror each other. The increasing impact of sibship size on education within Black groups coincides with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was passed 18 years after the earliest birth year of cohort 5. These results are consistent with the proposition that educational opportunities played a role in shaping reproductive trade-offs during the 1900s.

The effect of sibship size on education by race and birth cohort. Simulated male individuals (N = 2000) from each cohort are run through the trained model with varying sibship sizes for race and parental income. The plot depicts the predicted probabilities of the outcome variable for each circumstance

Simulated data also illustrates the effect of parental income on educational attainment, independent of race (Fig. 5). Unsurprisingly, individuals with lower parental income consistently had lower chances of attending college. This effect becomes more pronounced over time such that in later cohorts, parental income is a stronger cause of college attendance disparities than race. Again, this may be tied to reforms prohibiting racial discrimination in college admissions. Recent racial disparities in college attendance are probably more likely caused by disparities in family income and related social inequalities, rather than explicit racial exclusion, a conclusion supported by contemporary studies of education in the United States (Charles et al., 2007; Jez, 2008).

Lastly, one surprising finding revealed by simulated data is that while Black individuals with up to four siblings always have lower probabilities of completing four years of college than White individuals with the same number of siblings, Black individuals born between 1936 and 1955 with more than six siblings had higher probabilities of completing four years of college than White individuals with the same family size. Interpretations for this result are discussed in the following section.

Discussion

Although analyses of fertility across nations tend to support the general trend that decreases in fertility correspond to shifts toward industrialized economies, examining patterns of fertility decline within nations allows us to better understand how variations in this relationship materialize across different individuals. The results of my study demonstrate that the relationship between sibship size and educational attainment varies between racial groups in the 1900s and suggest that this variation may be responsive to the landscape of economic opportunities afforded to the individual. In postindustrial societies, parents can affect their children’s status by investing in their education, but fixed characteristics of an individual can be embodied in ways that negatively affect this pathway. In such cases, the ability of parents to improve their children’s status may be reduced, muting the benefit of trading offspring quantity for offspring status and therefore the incentive to reduce fertility.

My study rests on the assumption that a history of racial exclusion contributed to disparities in social mobility opportunities between Black and White individuals, creating distinct reproductive trade-offs for the two groups. Although the observed differences between cohorts do seem to align with relevant historical events, my data cannot speak on the mechanisms by which social conditions influence reproductive decision-making. I have suggested here that Black individuals experience fewer advantages in investing in education, primarily due to constraints on college acceptance and the diminished status benefits of holding a bachelor’s degree. My results are compatible with the first assertion; the relative advantage of having fewer siblings on education becomes more apparent after the prohibition of race-based college discrimination. However, in most recent Black cohorts, the negative effect of additional siblings on college attendance is greater than in previous cohorts, and even than in White groups of the same cohort. Based on the finding that the average wage difference between high school and college graduates is lower for Black individuals compared with their White counterparts (Economic Policy Institute, 2022), I would not expect the trade-offs between sibship size and education for the two groups to converge so conspicuously. It is possible that the monetary benefit of college for Black individuals, although smaller than for White individuals, is still significant enough motivate the pursuit of higher education. This could be clarified with data that follow wage differences across the early 1900s; if the current advantages of college education for Black individuals are still significantly greater than in the past, this would align with the trends seen in my model. Nevertheless, it is still worthwhile to consider alternative mechanisms through which this reproductive behavior may arise.

Given the important role of cultural transmission on human survival in novel environments, it is reasonable to speculate that social learning plays an important role in human reproductive psychology. Henrich and McElreath (2003) propose that individuals have context biases that predispose them to learn from people who display certain quantifiable characteristics. Prestige bias has commonly been invoked to explain the spread of low fertility from the social elite to other members of society. When high-status families reduce their family sizes, others will be responsive to this and copy their behavior with the intention of attaining similar status distinctions (Colleran, 2016). However, my data illustrate that pathways to economic success are not universal but rather depend on the structural circumstances faced by the individual or group. Studies show that children are more likely to copy models who share the same gender and language as them over models who differ (Taylor, 2013; Shutts et al., 2009). Likewise, it is reasonable to expect that people direct social learning toward models with shared identity markers when aspects of an individual’s identity govern important differences in their interactions with the environment. Social pressures to conform to within-group norms can also intensify this motivation (Durkee et al., 2019). This aspect of social learning could contribute to between-group differences in average fertility and explain why reproductive trade-offs have converged in recent years, despite a lack of convergence in economic benefits. As successful models of social mobility through education emerge in Black social circles, more people may be motivated to adopt this strategy. Moreover, if the differences in ecological realities between races become less distinct, people may be more inclined to copy the strategies of other races. Future work that examines how reproductive strategies are transmitted within communities or social networks could provide more robust insights about the effect of social learning on intergroup reproductive differences.

One surprising result seen in the counterfactual data was that for cohorts 4 and 5, Black individuals with more siblings showed a higher probability of having completed four years of college than White individuals with the same sibship size. This result sheds light on possible methodological limitations that could be improved upon in future studies. Because the GSS sample is more educated than the average American population, especially when it comes to Black Americans, this result may simply be a symptom of sampling bias. Since this bias appears to be more pronounced among Black respondents, resulting in a smaller Black–White education gap in the GSS data than in the census data, it is possible that the Black individuals sampled in the GSS represent highly educated portions of the population, whereas White individuals are comparatively more representative of the average. This would artificially raise the probability of college attendance for Black families, producing the illusion that large Black families have higher educational attainment than White ones.

Another possible explanation is that the model fails to account for variations in household composition. The variable reported in the GSS for sibship size does not specify the relatedness between siblings (i.e.,, full, half, step, or adoptive) nor the age differences between siblings. As a result, individuals reporting a larger number of siblings may be disproportionately represented by those who have many half and step siblings from their parents’ remarriage. Therefore, we do not know how much competition for parental resources occurred between each sibling. Moreover, individuals who had adult siblings during childhood could potentially see benefits to education if adult siblings were able to invest time or money in their younger siblings. Jokela et al. (2010) find that in the United States, Black men show larger increases in fertility from serial monogamy than White men. If this distinction means that individuals in Black families are more likely to have half and step siblings than those in White families, then this effect may be an important confounder of the observed differences in sibship size–education relationships between Black and White families. Future research can benefit from having more fine-tuned data about sibship composition.

Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to investigate the possible theoretical benefits of having a larger family in an industrial economy. Mithun (1973) observes how, in a predominantly Black community in the metropolitan United States, actions of mutual aid between family and community members are normalized. It has been proposed that cultural norms that prescribe a greater role in childcare to community and extended family members may weaken the negative relationship between family size and education (Ahn et al., 1998; Shavit & Pierce, 1991). Shavit and Pierce (1991) find that in Israel, whereas greater sibship size has a negative effect on education in Ashkenazi and Oriental Jews, for Moslem Arabs who put greater emphasis on extended family support, large sibships are associated with benefits to education. Moreover, children from smaller Arab families were disadvantaged, possibly because in cultures where community connections are important sources of reproductive support, those with weaker connections will have fewer children in the first place. This study sheds light on the importance of identifying from where resources are obtained and between whom resources must be divided. The distribution of resources in large families may not be as straightforward as trade-off models predict. Instead of sibling competition being zero-sum as assumed in standard behavioral ecology models, family members can work together to increase the total pot of family resources. For example, Hackman and Kramer (2021) show that in a Maya community with a mixed economic structure in which resources come from both traditional subsistence practices and participation in market economies, larger families have greater livelihood diversity, which can increase their household income and provide resilience to environmental or economic scarcity. This finding emphasizes the power that intra-family collaboration has on reducing the effect of sibling competition on later-life outcomes.

Overall, the results of this study highlight the limitations of assuming uniform reproductive strategies across diverse groups. While nationwide economic development will have downstream effects on all individuals, not everyone will have equal access to opportunities to increase status, leading to differences in reproductive trade-offs. A model of human reproduction that acknowledges these distinctions could explain variations in the timing of fertility decline both within and across populations. This research also highlights the crucial role of historical and cultural phenomena in comprehending behavioral patterns, even when adopting evolutionary perspectives. Furthermore, it stresses the importance of tailoring family planning initiatives to the unique challenges faced by different subgroups.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are available on the GSS Data Explorer website at gssdataexplorer.norc.org.

References

Alvergne, A., & Lummaa, V. (2014). Ecological variation in wealth-fertility relationships in Mongolia: The central theoretical problem of sociobiology not a problem after all? Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 281, 20141733. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1733

Andrews, D., & Leigh, A. (2009). More inequality, less social mobility. Applied Economics Letters, 16(15), 1489–1492. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504850701720197.

Anh, T. S., Knodel, J., Lam, D., & Friedman, J. (1998). Family size and children’s education in Vietnam. Demography, 35(1), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/3004027.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991–1013. https://doi.org/10.1257/00028280420002561.

Borgerhoff Mulder, M. (1998). The demographic transition: Are we any closer to an evolutionary explanation? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 13(7), 266–270. https://doi.org/S0169- 5347(98)01357-3

Burtless, G., & Jencks, C. (2003). American inequality and its consequences. In H. Aaron, J. M. Lindsay, and P. S. Nivolapp (Eds.), Agenda for the nation (pp. 61–108). Brookings. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/95399

Card, D., & Lemieux, T. (2000). Dropout and enrollment trends in the post-war period: What went wrong in the 1970s? National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 7658. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w7658/w7658.pdf.

Charles, C. Z., Roscigno, V. J., & Torres, K. C. (2007). Racial inequality and college attendance: The mediating role of parental investments. Social Science Research, 36(1), 329–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.02.004.

Clark, G., & Hamilton, G. (2006). Survival of the richest: The Malthusian mechanism in pre-industrial England. The Journal of Economic History, 66(3) 707–736. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050706000301

Colleran, H. (2016). The cultural evolution of fertility decline. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 371, 20150152. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0152.

Colleran, H., & Snopkowski, K. (2018). Variation in wealth and educational drivers of fertility decline in 45 countries. Population Ecology, 60, 155169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10144-018-0626-5.

Durkee, M. I., Gazley, E. R., Hope, E. C., & Keels, M. (2019). Cultural invalidations: Deconstructing the acting White phenomenon among Black and Latinx college students. Culture Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(4), 451. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000288.

Durlauf, S. (1996). A theory of persistent income inequality. Journal of Economic Growth, 1, 75–93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40215882.

Economic Policy Institute. (2022). State of working America data library (wages by education) [data set]. https://www.epi.org/data/#?subject=wage-education

Eloundou-Enyegue, P. M., & Williams, L. B. (2006). Family size and schooling in sub-saharan Africa settings: A reexamination. Demography, 43(1), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2006.00002.

Gilbert, K. L., Ransome, Y., Dean, L. T., DeCaille, J., & Kawachi, I. (2022). Social capital, black social mobility, and health disparities. Annual Review of Public Health, 43, 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052020-112623.

Goldin, C., & Katz, L. (1999). Education and income in the early 20th century: Evidence from the prairies. Journal of Economic History, 60(3), 7882–7818. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700000334.

Goodman, A., Ilona, K., & Lawson, D. W. (2012). Low fertility increases descendant socioeconomic position but reduces long-term fitness in a modern post-industrial society. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 279: 4342–4351. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.1415.

Hackman, J. V., & Kramer, K. L. (2021). Balancing fertility and livelihood diversity in mixed economies. PLoS One, 16(6), e0253535. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253535

Hagen, E. H., Barrett, H. C., & Price, M. E. (2006). Do human parents face a quantity-quality tradeoff? Evidence from a Shuar community. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 130, 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1002/sjpa.20272.

Harcourt, A. H. (1987). Dominance and fertility among female primates. Journal of Zoology London, 213, 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1987.tb03721

Harris, B. (2022). Racial inequality in the United States. U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/racial-inequality-in-the-united-states.

Haynes, B. (2006). Black undergraduates in higher education: An historical perspective. African Americans: Struggle for Recognition in the Academy, 17(2), 8–21.

Henrich, J., & McElreath, R. (2003). The evolution of cultural evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology, 12, 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.10110.

Hopcroft, R. L. (2019). Sex difference in the association of family and personal income and wealth with fertility in the United States. Human Nature, 30(4), 477–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-019-09354-4.

Jez, S. J. (2008). The influence of wealth and race in four-year college attendance. Center for Studies in Higher Education, University of California, Berkeley. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0cc2x5tj

Jokela, M., Rotkirch, A., Rickard, I. J., Pettay, J., & Lummaa, V. (2010). Serial monogamy increases reproductive success in men but not in women. Behavioral Ecology, 21(5), 906–912. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arq078.

Kaplan, H. S., Lancaster, J. B., Johnson, S. E., & Bock, J. A. (1995). Does observed fertility maximize fitness among New Mexican men? A test of an optimality model and the new theory of parental investment in the embodied capital of offspring. Human Nature, 6(4), 325–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02734205

Kremer, M., & Chen, D. L. (2002). Income distribution dynamics with endogenous fertility. Journal of Economic Growth, 7, 277–258. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020154031908.

Lack, D. (1947). The significant of clutch-size. Ibis, 89, 302–352. https://doi.org/10.111/j.1474-919X.1947.tb04155.x.

Lawson, D. W., & Borderhoff Mulder, M. (2016). The offspring quantity-quality trade-off and human fertility variation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 371, 2015014. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0145.

Lawson, D. W., & Mace, R. (2009). Trade-offs in modern parenting: A longitudinal study of sibling competition for parental care. Evolution and Human Behavior, 30, 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.12.001.

Lawson, D. W., & Mace, R. (2010). Optimizing modern family size: Trade-offs between fertility and the economic costs of reproduction. Human Nature, 21, 39–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-010-9080-6.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Wilson, C. (1986). Modes of production secularization and the pace of the fertility decline in Western Europe, 1870–1930. In A. J. Coale, & S. C. Watkins (Eds.), The decline of fertility in Europe (pp. 261–292). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400886692-011

Majolo, B., Lehmann, J., de Bortoli, V. A., & Schino, G. (2012). Fitness-related benefits of dominance in primates. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 147, 652–660. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22031.

Maralani, V. (2008). The changing relationship between family size and educational attainment over the course of socioeconomic development: Evidence from Indonesia. Demography, 43(3), 693–717. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0013.

McElreath, R. (2021). rethinking: statistical rethinking book package. R package version 2.21. https://github.com/rmcelreath/rethinking.

Meij, J. J., Van Bodegom, D., Ziem, J. B.… and, & Westendorp, R. G. J. (2009). Quality-quantity trade-off of human offspring under adverse environmental conditions. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22, 1014–1023. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01713.x.

Mithun, J. S. (1973). Cooperation and solidarity as survival necessities in a black urban community. Urban Anthropology, 2(1), 025–034. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40552636.

National Opinion Research Center (NORC). (2022). General social surveys (1972–2022) [Data set]. University of Chicago. https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org/

Nettle, D., & Pollet, T. V. (2008). Natural selection on male wealth in humans. The American Naturalist, 175(5), 658–666. https://doi.org/10.1086/591690.

Pallikadavath, S., & Wilson, C. (2005). A paradox within a paradox: Schedules caste fertility in Kerala. Economic and Political Weekly, 40(28), 3085–3093. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4416878.

Piacentini, J., Frazis, H., Meyer, P. B., Schultz, M., & Sveikauskas, L. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on labor markets and inequality. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Working Paper 551. https://www.bls.gov/osmr/research-papers/2022/pdf/ec220060.pdf

Scelza, B. A. (2010). Fathers’ presence speeds the social and reproductive careers of sons. Current Anthropology, 51(2), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1086/651051.

Shavit, Y., & Pierce, J. L. (1991). Sibship size and educational attainment in nuclear and extended families: Jews in Israel. American Sociological Review, 56(3), 321–330. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096107.

Shenk, M. K., Kaplan, H. S., & Hooper, P. L. (2016). Status competition, inequality, and fertility: Implications for the demographic transition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 375, 20150150. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0150.

Shutts, K., Kinzler, K. D., McKee, C. B., & Spelke, E. S. (2009). Sensitivity to communicative relevance tells young children what to imitate. Developmental Science, 12(6), 1013–1019. https://doi.org/10.111/j.1467-7687.2009.00861.x.

Stulp, G., Sear, R., Schaffnit, S. B., Mills, M. C., & Barrett, L. (2016). The reproductive ecology of industrial societies, part II: The association between wealth and fertility. Human Nature, 27, 445–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-016-9272-9.

Taylor, M. G. (2013). Gender influences on children’s selective trust of adult testimony. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 115(4), 672–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2013.04.003.

US Census Bureau (2023). Table A-2. Percent of people 25 years and over who have completed high school or college, by race, Hispanic origin and sex: selected years 1940–2022. [Data set]. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/educational-attainment/cps-historical-time-series.html.

Van Bavel, J. (2006). The effect of fertility limitation on intergenerational social mobility: The quality-quantity trade-off during the demographic transition. Journal of Biosocial Sciences, 38, 553–569. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932005026994.

Vandenbroucke, G. (2016). The link between fertility and income. Saint Louis Federal Reserve Bank. https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2016/december/link-fertility-income.

Vining, D. R. (1986). Social versus reproductive success: The central theoretical problem of human sociobiology. Behavior and Brian Science, 9, 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00021968.

Von Rueden, C. R., & Jaeggi, A. V. (2016). Men’s status and reproductive success in 33 nonindustrial societies: Effects of subsistence, marriage system, and reproductive strategy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(39), 10834–10829. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606800113

Funding

Partial financial support was received from the University of California, Los Angeles. The author has no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S. Racial and Temporal Differences in Fertility–Education Trade-Offs Reveal the Effect of Economic Opportunities on Optimum Family Size in the United States. Hum Nat 35, 134–152 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-024-09472-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-024-09472-8