Abstract

Primary neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) of the larynx and head and neck are an uncommon and heterogeneous group of neoplasms categorized by the 2017 WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors as: (a) well-differentiated (WD-NEC), (b) moderately-differentiated (MD-NEC), and (c) poorly-differentiated (PD-NEC) with small cell and large cell types. The classification incorporates elements of differentiation and grading and closely correlates to the 5-year disease specific survival of 100, 52.8, 19.3 and 15.3% for each diagnostic category. These survival rates are based on historical data limited by the previous lack of standard pathologic diagnostic criteria. The classification has de-emphasized the use of the terms “carcinoid” and “atypical carcinoid” as diagnostic categories. The adoption of uniform pathologic criteria for the classification of NECs of the head and neck should enable the design of high quality studies in order to understand the molecular alterations of these neoplasms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As knowledge and understanding in pathology evolve, nomenclature and classifications also change to reflect those advances. The current classification of neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) of the larynx and head and neck is the result of nearly 50 years of clinical observations and original work by numerous investigators [1,2,3,4]. Primary NECs of the larynx and head and neck are an uncommon and heterogeneous group of neoplasms that historically have been classified using the terminology and diagnostic criteria of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the intestine and more recently lung [1,2,3, 5]. In 1969 Goldman et al. [1] published what is generally regarded as the first description of a laryngeal well-differentiated neuroendocrine (WD-NEC). In this single case report, the authors discussed a “typical carcinoid tumor” involving the anterior commissure and the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis of a 73 year-old man, who eventually developed multiple cervical lymph node and skin metastases. In 1988 Wenig et al. [2] published their classic landmark study in which the lack of standardization in terminology utilized in diagnosing laryngeal NECs was highlighted and a new classification system based on the system employed for pulmonary NECs was proposed. These investigators categorized laryngeal NECs as “well differentiated” (synonymous with carcinoid), “moderately differentiated” (synonymous with atypical carcinoid), and “poorly differentiated” (synonymous with small cell carcinoma, both oat cell and intermediate cell variants) [2]. The latter classification system lacked a category of “large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma” because validated criteria for the diagnosis of pulmonary LC-NEC were only proposed in 1991 [6]. In 2005, Greene and collaborators reported the first example of a laryngeal LC-NEC using the standardized diagnostic criteria for LC-NEC in the lung [7].

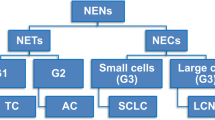

The 2017 WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors lists 3 types of head and neck and laryngeal NECs (Table 1): (a) well-differentiated (WD-NEC), (b) moderately-differentiated (MD-NEC), and (c) poorly-differentiated (PD-NEC) with small cell and large cell types [4]. This terminology incorporates elements of differentiation and grading and as such WD-NEC represents a low-grade (grade I) carcinoma, MD-NEC is an intermediate-grade (grade 2) carcinoma and SC-NEC and LC-NEC represent high-grade (grade 3) malignancies [2, 3]. Another feature of this classification is that the terms “carcinoid” and “atypical carcinoid” are de-emphasized and used as synonyms only. The later development is a subtle but significant departure from the 2005 WHO Classification when the terms “carcinoid” and “atypical carcinoid” were the preferred terminology and there were no criteria for the diagnosis of LC-NEC [5].

Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (WD-NEC)

WD-NECs are distinctly rare and represent the least common type of NEC affecting the larynx. In the meta-analysis of the English literature on NECs of the larynx by ven der Laan et al. [8], 23 of 436 laryngeal NECs were accepted as examples of WD-NECs accounting for 5.27% of all laryngeal NECs. WD-NECs are slightly more common in men than women affecting patients in the seventh decade of life (age range 43–72 years). Most patients (75%) have a history of heavy tobacco use. Approximately 95% of WD-NECs arise in the supraglottic larynx and 83% of cases present with stage I disease [8].

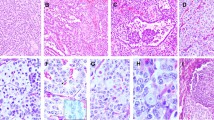

Microscopically WD-NECs are defined as neoplasms with neuroendocrine morphology, mitotic rate of less than 2 mitoses per 2 mm2 or 10 HPF, and absence of necrosis (Fig. 1). WD-NECs grow in submucosal nests, trabeculae and solid sheets of round to slightly oval or spindle cells with moderate amounts of pale eosinophilic, amphophilic to granular (oncocytic or oncocytoid) cytoplasm [9,10,11]. A glandular pattern or rosettes can also be noted [12]. Characteristically, the tumor nuclei contain stipple “salt and pepper” chromatin and nucleoli are inconspicuous or absent. Common immunohistochemical markers used in the diagnosis of NECs of the larynx are listed in Table 2.

Well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (WD-NEC). The tumor is composed of intermediate size cells arranged in nests and sheets. The cytoplasm is pale and the nuclei are slightly irregular with stipple or speckled chromatin. No mitoses or nucleoli are present thus qualifying for WD-NEC (a). Ki-67 stain with a low LI (b)

The value of the published data regarding the long-term behavior of WD-NECs of the larynx is limited due to the rarity of the tumor and the historic variability of the precise pathologic criteria used to establish the diagnosis; however, these neoplasms appear to be low-grade malignancies with a low but definitive risk of regional lymph node and distant metastases, particularly to the skin [1, 11]. Although the 5-year disease specific survival (DSS) is reported as being 100%, the 5-year distant-metastasis free survival rate drops to 83.3% [8] and several single case reports—including the original publication by Goldman et al.—described patients dying of their disease at 18, 24, 33, and 80 months after initial diagnosis [1, 10, 11, 13].

Moderately-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (MD-NEC)

MD-NEC is the second most common primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx representing 37% of all laryngeal NECs [8]. Median age at presentation is 63 years (range 20–83). Most patients affected by MD-NEC are male (70%) and smokers (94%). The majority of the tumors present with stage I–II disease (65%) with the remaining 35% being stage III–IV disease. 93% of cases arise in the supraglottic larynx [8].

Microscopically this group of neoplasms is equivalent to “atypical carcinoid tumors” and is defined as tumors with neuroendocrine morphology with 2–10 mitoses per 2 mm2 or 10 HPF, and/or necrosis. Similar to WD-NECs, MD-NECs grow in nests, trabeculae and sheets of round to slightly oval or spindle cells with moderate amounts of pale eosinophilic, amphophilic to granular cytoplasm [2, 14,15,16] (Fig. 2). A glandular pattern or rosettes can also be noted [2, 14, 16]. Characteristically, the tumor nuclei contain stipple “salt and pepper” chromatin or may show more nuclear atypia and irregularities with prominent nucleoli. The tumor nests frequently show central “comedo” type necrosis. Immunohistochemical markers used in the pathologic diagnosis of MD-NECs are listed in Table 2.

MD-NECs are aggressive malignancies with a 5 year-DSS of 53% [8]. Wenig et al. [2] in their series of “moderately differentiated” NEC indicated that 38% (18/48) of patients had died with tumor. It has been widely acknowledged that some published examples of MD-NECs (or “atypical carcinoids”) would be reclassified as LC-NECs using current diagnostic criteria [3, 5, 14, 15, 17, 18].

Poorly-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinoma, Small Cell Type (SC-NEC)

SC-NEC is the most common primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx representing 41% of all laryngeal NECs [8]. Median age at presentation is 59 years (range 23–91). Most patients affected are male (81%) and smokers (95%) presenting with Stage IV disease (67%). As is the case with all types of laryngeal NECs, the supraglottic larynx is the most common site of origin (58%).

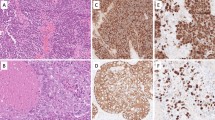

SC-NEC is microscopically defined as: “(a) tumor cells with small size (generally less than the diameter of 3 small resting lymphocytes), (b) scant cytoplasm, (c) finely granular chromatin, absent or inconspicuous nucleoli, (d) high mitotic rate (11 or greater per 2 mm2 or 10 HPF) and (e) frequent necrosis” [15, 19, 20] (Fig. 3). Architecturally SC-NEC is characterized by tumor cells arranged in variably sized nests, sheets and trabeculae with occasional peripheral palisading and rosette formation. Lymphovascular and perineural invasion, nuclear moulding, necrosis, apoptosis and DNA encrustation of blood vessel walls (Azzopardi phenomenon) are frequent findings [15, 19]. SC-NECs are extremely aggressive malignancies with a 5 year-DSS of 19.3% [8] despite multimodal therapy.

Poorly-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinoma, Large Cell Type (LC-NEC)

LC-NECs of larynx are uncommon comprising only 7% of all laryngeal NECs [8]. Median age at presentation is 60 years (range 31–81). Most patients affected are male (70%) and smokers (91%) presenting with stage IV disease (70%). The supraglottic larynx is the most common site of origin (81%) [8].

Microscopically LC-NEC is defined as “(a) tumor with a neuroendocrine morphology; organoid nesting, palisading, rosettes, trabeculae; (b) high mitotic rate: 11 or greater per 2 mm2 (10 HPF); (c) necrosis; (d) abundant cytoplasm with vesicular nuclei containing coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli; and (e) positive staining with one or more neuroendocrine markers” (Table 2) [19, 21,22,23,24,25] (Fig. 4).

LC-NECs are aggressive malignancies with a 5 year-DSS of 15.3% [8]. In a recent report of high-grade NECs in the larynx, Deep et al. [21] described five cases of LC-NEC with two patients dying of disease 3 and 62 months after initial therapy, one was alive with disease at 41 months and two were alive with no disease 26 and 29 months after diagnosis. In the report of 10 laryngeal LC-NECs by Lewis et al. [22], nine patients (90%) presented with stage IV disease and 60% died of their disease.

Pathologic Grading and Ki67 Labeling Index (LI)

The adoption of uniform diagnostic criteria and terminology for head and neck NECs in the 2017 WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors is a significant step forward because it should allow comparison and validation of study results from different investigators and institutions thus advancing the understanding of the clinical behavior—including the role of Ki-67 proliferative index (PI)—and underlying molecular abnormalities of these uncommon neoplasms. Given the rarity of NECs in the larynx and head and neck collaborative studies will be necessary to achieve meaningful results.

The terminology employed in the 2017 WHO classification of NECs of the head and neck explicitly incorporates elements of differentiation and grading and as such WD-NECs represents a low-grade (grade 1) carcinoma, MD-NECs is an intermediate grade (grade 2) carcinoma and SC-NEC and LC-NEC represent high grade (high 3) malignancies [2, 3] and in that regard has more in common with the lung classification of NECs where typical and atypical carcinoid tumors represent low and intermediate grade malignancies and small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas represent high grade carcinomas [26]. In contrast, differentiation and grading are discrete criteria in the classification of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) of the GI and pancreatobiliary tract with grading becoming of paramount importance in well-differentiated NETs where the behavior is best predicted by a combination of clinical and pathologic features including mitotic activity and Ki-67 labeling index (Ki-67 LI) [27, 28]. Table 3 contrasts the different terminologies and classification of neuroendocrine tumors of the head and neck, lung and GI and pancreatobiliary tracts.

Currently there is no sufficient data to draw conclusions about the value of Ki-67 LI in the diagnosis and classification of NECs of the head and neck; however, some studies suggest that Ki-67 LI might be potentially useful [24, 29]. In a study of 23 NECs of the head and neck by Kao et al. [24], 2 of their 7 LC-NECs revealed discordance between mitotic counts and Ki-67 LI (6 and 9 MF/10 HPF vs 30% and 53% Ki-67 LI) resulting in the re-classification of these 2 cases as LC-NEC rather than MD-NEC. Both patients died of their disease (53 and 10 months follow-up). In a couple of studies of laryngeal NECs, isolated examples of discrepancies between mitotic rate and Ki-67 LI have been found [22, 29]. Nonetheless other studies have found good concordance between pathologic classification, mitotic counts and Ki-67 LI [23, 30]. Larger studies are necessary to investigate the added value of Ki-67 LI in the diagnosis and classification of NECs of the larynx and head and neck.

Molecular Pathology

Ideally a modern pathologic classification should reflect underlying genetic and molecular abnormalities as in the classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the lung where low- and intermediate-grade neoplasms (carcinoid and atypical carcinoid) are characterized by mutations of MEN1 and related chromatin modifiers genes whereas high-grade carcinomas are characterized by inactivating mutations of the RB and TP53 genes [31]. In contrast, there is only sparse data addressing the molecular biology of laryngeal and head and neck NECs (Table 4), therefore it is unknown if NECs of the head and neck represent a diverse group of epithelial malignancies sharing neuroendocrine differentiation or one disease with a range of differentiation and grades. Notably, more than 90% of laryngeal NECs are associated with tobacco smoking [8], an association inviting the hypothesis that the molecular abnormalities noted in pulmonary LC-NEC and SC-NEC might also be at play in the pathogenesis of laryngeal NECs. Alos et al. [30] results suggests that most high-grade NEC of the head and neck, including larynx, exhibit dysregulation of the Rb pathway resulting in p16 accumulation and Rb loss of expression. In addition these authors also found high p53 expression in high-grade NECs, a finding suggestive of TP53 mutations. Kao et al. [24] also found p53 overexpression in 92% of their high-grade NECs whereas none of their WD-NEC or MD-NECs exhibited p53 increased expression. In a single case report of a combined NEC and SCC of the maxillary sinus, Frachi et al. found a missense mutation of TP53 the NEC component but not in the SCC component [32]. In contrast, Halmos et al. [29] found no p53 overexpression in a study of 10 laryngeal NECs. Rare examples of laryngeal MD-NEC and LC-NEC associated to HPV18 and HPV16 have reported raising additional questions regarding additional molecular pathways for the development of NECs in the head and neck [29]. More studies are needed to understand the genetic and molecular abnormalities of NECs of larynx and head and neck. Table 4 summarizes some of the molecular abnormalities found in NECs of the head and neck.

Mixed Neuroendocrine-Nonneuroendocrine Neoplasms (MiNENs) of the Head and Neck

The coexistence of neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components in carcinomas of the head and neck is a known but rare phenomenon [32,33,34]. Whereas the WHO classifications of endocrine organs and GI system recommend that mixed neoplasms are those in which either component represent at least 30% of the tumor, no such recommendation exists for mixed neuroendocrine-nonneuroendocrine carcinomas of the head and neck. Most MiNENs of the head and neck represent a combination of SC-NEC and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with less common examples of SC-NEC and adenocarcinomas; particularly in the nasal cavity; and rare examples of LC-NEC and SCC and MD-NEC and SCC [25, 35].

Conclusions

Primary NECs of the larynx and head and neck are an uncommon and heterogeneous group of neoplasms categorized by the 2017 WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors as: (a) well-differentiated (WD-NEC), (b) moderately-differentiated (MD-NEC), and (c) poorly-differentiated (PD-NEC) with small cell and large cell types. This classification incorporates elements of differentiation and grading and de-emphasized the use of the terms “carcinoid” and “atypical carcinoid” as diagnostic categories. The adoption of uniform diagnostic criteria and terminology for head and neck NECs should allow the design of high quality studies and comparison and validation of results from different investigators and institutions which should advance our understanding of the clinical and molecular alterations involved in the genesis of these neoplasms. Possible areas of investigation and outstanding questions are listed in Table 5.

References

Goldman NC, Hood CI, Singleton GT. Carcinoid of the larynx. Arch Otolaryngol. 1969;90:64–7.

Wenig BM, Hyams VJ, Heffner DK. Moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: a clinicopathologic study of 54 cases. Cancer. 1988;62:2658–76.

Lewis JS Jr, Ferlito A, Gnepp DR, et al. Terminology and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the larynx. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1187–93.

Perez-Ordonez B, Bishop JA, Gnepp DR, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR et al, editors. WHO classification of head neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 95–8.

Barnes L. Tumours of the hypopharynx, larynx, and trachea: neuroendocrine tumors. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P et al, editors. Pathology and genetics head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2005. p. 135–9.

Travis WD, Linnoila RI, Tsokos MG, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung with proposed criteria for large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: an ultrastructural, immunohistochemical, and flow cytometric study of 35 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:529–53.

Greene L, Brundage W, Cooper K. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: a case report and a review of the classification of this neoplasm. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:658–61.

van der Laan TP, Plaat BE, van der Laan BF, et al. Clinical recommendations on the treatment of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: A meta-analysis of 436 reported cases. Head Neck. 2015;37:707–15.

Duvall E, Johnston A, McLay K, et al. Carcinoid tumour of the larynx: a report of two cases. J Laryngol Otol. 1983;97:1073–80.

Stanley RJ, DeSanto LW, Weiland LH. Oncocytic and oncocytoid carcinoid tumors (well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas) of the larynx. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;112:529–35.

Schmidt U, Metz KA, Schrader M, et al. Well-differentiated (oncocytoid) neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx with multiple skin metastases: a brief report. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:272–4.

Bapat U, Mackinnon NA, Spencer MG. Carcinoid tumours of the larynx. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:194–7.

Wang Q, Chen H, Zhou S. Typical laryngeal carcinoid tumor with recurrence and lymph node metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:9028–31.

Chung JH, Lee SS, Shim YS, et al. A study of moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas of the larynx and an examination of non-neoplastic larynx tissue for neuroendocrine cells. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1264–70.

Milroy CM, Rode J, Moss E. Laryngeal paragangliomas and neuroendocrine carcinomas. Histopathology. 1991;18:201–9.

Chung EJ, Baek SK, Kwon SY, et al. Moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;1:217–20.

Capelli M, Bertino G, Morbini P, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the upper airways: a small case series with histopathological considerations. Tumori. 2007;93:499–503.

Woodruff JM, Senie RT. Atypical carcinoid tumor of the larynx: a critical review of the literature. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1991;53:194–209.

Woodruff JM, Huvos AG, Erlandson RA, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the larynx. a study of two types, one of which mimics thyroid medullary carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:771–90.

Olofsson J, van Nostrand AW. Anaplastic small cell carcinoma of larynx: case report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1972;81:284–7.

Deep NL, Ekbom DC, Hinni ML, et al. High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: the mayo clinic experience. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125:464–9.

Lewis JS Jr, Spence DC, Chiosea S, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: definition of an entity. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4:198–207.

Kusafuka K, Abe M, Iida Y, et al. Mucosal large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the head and neck regions in Japanese patients: a distinct clinicopathological entity. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:704–9.

Kao HL, Chang WC, Li WY, et al. Head and neck large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma should be separated from atypical carcinoid on the basis of different clinical features, overall survival, and pathogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:185–92.

Thompson ED, Stelow EB, Mills SE, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the head and neck: a clinicopathologic series of 10 cases with an emphasis on HPV status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:471–8.

Brambilla E, Beasley MB, Austin J, et al. Neuroendocrine tumours. In: Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP et al, editors. WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus & heart. Lyon: IARC; 2015. p. 63–77.

Kloppel G, Couverland A, Hruban RH, et al. Neoplams of the neuroendocrine pancreas. In: Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Kloppel G et al, editors. WHO classification of tumours of endocrine organs. Lyon: IARC; 2017. p. 209–39.

Kim JY, Hong SM. Recent updates on neuroendocrine tumors from the gastrointestinal and pancreatobiliary tracts. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:437–48.

Halmos GB, van der Laan TP, van Hemel BM, et al. Is human papillomavirus involved in laryngeal neuroendocrine carcinoma? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:719–25.

Alos L, Hakim S, Larque AB, et al. p16 overexpression in high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the head and neck: potential diagnostic pitfall with HPV-related carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2016;469:277–84.

Pelosi G, Sonzogni A, Harari S, et al. Classification of pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors: new insights. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2017;6:513–29.

Franchi A, Rocchetta D, Palomba A, et al. Primary combined neuroendocrine and squamous cell carcinoma of the maxillary sinus: report of a case with immunohistochemical and molecular characterization. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:107–13.

La Rosa S, Furlan D, Franzi F, et al. Mixed exocrine-neuroendocrine carcinoma of the nasal cavity: clinicopathologic and molecular study of a case and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:76–84.

La Rosa S, Sessa F, Uccella S. Mixed neuroendocrine-nonneuroendocrine (MiNENs): unifiying the concept of a heterogeneous group of neoplams. Endocr Pathol. 2016;27:284–311.

Davies-Husband CR, Montgomery P, Premachandra D, et al. Primary, combined, atypical carcinoid and squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx: a new variety of composite tumour. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124:226–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article is a review of published literature and does not contain any specific intervention or investigation of human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perez-Ordoñez, B. Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Larynx and Head and Neck: Challenges in Classification and Grading. Head and Neck Pathol 12, 1–8 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-018-0894-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-018-0894-6