Abstract

Purpose

CD44v6 plays a controversial role in tumor progression and patient outcome in colorectal cancer by plenty of conflicting reports. The purpose of this study was to profile the intratumoral heterogeneity of CD44v6 in rectal cancer and investigate its role in lymph node metastasis.

Methods

Sixty patients were included in this study. Immunohistochemistry for CD44v6 was performed in normal mucosa, primary tumor, and lymph node metastasis with whole tissue sections. The staining intensity in tumor center and invasive front was separately measured. Sampling bias was evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR with 15 pairs of frozen tissues from different sites of the primary tumor.

Results

CD44v6 expression increased from normal mucosa to primary tumor to lymph node metastasis. Multiple intratumoral staining patterns was observed in primary tumor, and CD44v6 expression in invasive front was significantly higher than that in tumor center. In addition, mRNA expression levels differed across different geographical regions of the tumor. No association between CD44v6 expression and lymph node metastasis was revealed.

Conclusions

Substantial intratumoral heterogeneity of CD44v6 exists in rectal cancer that impacts the outcome of individual studies. CD44v6 expression should be assessed in a more precise way with a specified staining pattern and in a designated location.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The v6 containing CD44 isoform (CD44v6) is a member of CD44 family that is generated through alternative mRNA splicing [1]. It has been extensively studied in the past few decades since it is involved in many important roles in tumor development and progression. Evidence showed that CD44v6 inversely correlated with cell differentiation, contributed to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and conferred malignant cells with cancer stem cell properties [2–5]. However, the prognostic role of CD44v6 in colorectal cancer remains controversial by plenty of conflicting reports. In 2009, Zlobec et al. found that loss of membranous CD44v6 expression in colorectal cancer was significantly associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis via tissue microarray analysis with a large sample size. The authors also summarized the previous publications and found that 35 % showed adverse effect, 18 % showed favorable effect, and 47 % showed no effect between CD44v6 expression and prognostic outcome [6]. Recently, Wang et al. and Afify et al. reported that up-regulation of CD44v6 contributed to colorectal carcinogenesis, whereas down-regulation of the protein promoted cancer metastasis [7, 8].

Previously, we found that CD44v6 in colorectal cancer exhibited diverse expression patterns, implicating the remarkable intratumoral heterogeneity in the tumor which has not been reported. Intratumoral heterogeneity a common phenomenon in tumor as subclones of malignant cells sprout across different geographical regions and evolve over time [9]. It has drawn increasing recognition that the heterogeneity impact and pose challengers for the diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in clinic [10, 11]. In this study, the intratumoral heterogeneity of CD44v6 in rectal cancer was profiled, and the prognostic value in lymph node metastasis was investigated.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

Consecutive patients with primary rectal adenocarcinoma who underwent curative surgery in the Department of Surgical oncology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, between June 2013 and December 2013 were analyzed retrospectively. The following patients were excluded: (1) those with family history of colorectal cancer; (2) those with inflammatory bowel disease; (3) those with neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy; or (4) those with the number of lymph nodes less than ten in patients without lymph node metastasis. Finally, 30 patients with or without regional lymph node metastasis (LN− and LN+), respectively, were randomly selected for immunohistochemical staining. The paraffin-embedded archival specimens of primary tumor, adjacent non-tumor mucosa, and lymph nodes of each subject were obtained, and 3.5 μm sections were cut. The clinicopathological data are listed in Table 1. Moreover, 15 patients with a pair of frozen tissue samples, one from the central area and the other from the margin of the primary tumor, were selected for quantitative real-time PCR analysis. This study was approved by the clinical ethical committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Zhejiang, China (No. 2014055). And all the specimens were obtained after written informed consent.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical detection and evaluation of CD44v6 was performed as described in our previous publication [12]. Briefly, sections were incubated with the primary antibody CD44v6 (Abcam, USA, VFF7, 1:500), and visualized using the Polink-1 HRP DAB Detection System (ZSGB-BIO, China). The immunoreactivity and staining pattern of CD44v6 were evaluated under a light microscope (Olympus BX53, Japan). In each section, ten random microscopic fields in primary tumor and three in adjacent non-tumor mucosa and lymph nodes were photographed (×400). Then mean optical density (MOD) were measured using Image-Pro Plus6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, USA). Of note, stromal area in tumor or mucosa was manually excluded. In addition, MOD in the tumor center and invasive front of the primary tumor were analyzed with five random microscopic fields, respectively.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Tissue samples were collected from different sites of the primary tumor (Fig. 5A). a is from the central area, b is from the margin area, and c is from the adjacent normal mucosa. They were conserved at −80 °C and grinded in liquid nitrogen. a was dichotomized as a1 and a2 after grind. Total RNA was extracted by TRIzol method (Invitrogen, USA) followed by reverse-transcription using the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in triplicate by the ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HPRT1 was used as an endogenous control [13]. The primer sequences were: CD44v6: forward, 5′-AGGAACAGTGGTTTGGCAAC-3′, reverse, 5′-CGAATGGGAGTCTTCTTTGG-3′; HPRT1: forward, 5′-GGCGTCGTGATTAGTGAT-3′, reverse, 5′-CGTTCAGTCCTGTCCATAA-3′. Relative fold changes in CD44v6 mRNA expression in tumor were determined using the comparative CT method by normalizing to adjacent mucosa.

Statistical analyses

Both MOD and relative fold changes were comply with abnormal distribution and expressed as median (range). The Mann–Whitney U-test, Wilcoxon signed ranks test, or Spearman rank correlation was used as appropriate. The Bland–Altman plot was used to demonstrate the difference of MOD between tumor center and invasive front. All the statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistic v21.0 software (IBM Co., USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in a two-tailed manner.

Results

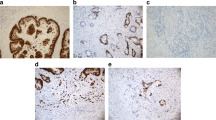

Overview of CD44v6 expression in rectal cancer tissues

Immunohistochemical analysis showed that CD44v6 expression was observed in 51 (85 %) primary rectal tumor, 45 (75 %) adjacent normal mucosas, and 25 (83 %) lymph node metastases. The typical results of negative or positive staining were demonstrated in Fig. 1. In the mucosa, CD44v6-positive cells were mainly located in the bottom of the crypt epithelia, while in 21 (35 %) cases positive staining was observed in the top area of the stromal cells. In the primary tumor, obvious intratumoral heterogeneity of CD44v6 expression was revealed. First, positive malignant cells were not evenly distributed that showed inhomogeneous from the tumor center to the invasive front. Second, CD44v6 protein was subcellularly localized to the cell membrane (10 %), the cytoplasm (6.7 %), the apical membranous portion of the lumen (5 %), or combination of them (78.3 %) (Fig. 2A–C). Third, CD44v6 expression could be also distinctly detected in non-cancerous compartment, such as the cell debris in glandular lumen (6.7 %), the entrained adenoma cells (3.3 %), or the stromal cells (13.3 %) (Fig. 2D–F). In the lymph node metastasis, expression of CD44v6 was inclined to present in the “all-or-none” pattern with less heterogeneity.

Intratumoral staining patterns of CD44v6 in primary tumor. CD44v6 was subcellularly localized to the cell membrane (A), the cytoplasm (B), the apical membranous portion of the lumen (C). And CD44v6 expression was also observed in the glandular lumen (D), the entrained adenoma cells (E), or the stromal cells (F) (Bar 50 μm)

Expression of CD44v6 in primary tumor, adjacent mucosa, and lymph node metastasis

In patients with lymph node metastasis, the MOD of CD44v6 was significantly increased from adjacent mucosa to primary tumor and then to lymph node metastasis (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, P = 0.015 and P = 0.005) (Fig. 3A). The MOD value in primary tumor was positively correlated with that in lymph node metastasis, though some outliers or exceptional points were observed (Spearman, r = 0.482, P = 0.007) (Fig. 3B). However, no significant correlation was revealed between adjacent mucosa and primary tumor. No statistical associations were revealed between CD44v6 expression and tumor size, pathological type, tumor grade, vascular and perineural invasion, local invasion, or lymph node metastasis.

Scatter diagram of CD44v6 expression in patients with lymph node metastasis. The MOD value was significantly increased from normal mucosa to primary tumor to lymph node metastasis (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, P = 0.015 and P = 0.005) (A). A positive correlation between primary tumor and lymph node metastasis was revealed with some outliers (red arrows) (B)

Expression of CD44v6 in tumor center and invasive front

In the primary tumor, 16 (26.7 %) sections showed apparently inconsistent positive intensity between the tumor center and the invasive front (Fig. 4A). Therefore, the MOD value in the two compartments was measured separately, which was positively correlated with each other (Spearman, r = 0.558, P < 0.001). However, the MOD value in the tumor center was significantly lower than it in the invasive front (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, P = 0.022) (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the Bland–Altman plot showed that the difference between tumor center and invasive front increased along with the average staining intensity (Fig. 4C). No associations were revealed between CD44v6 expression in tumor center or invasive front or Front/Center ratio and the clinicopathologic features described above.

CD44v6 expression in tumor center and invasive front. Typical results of inconsistent positivity between the tumor center and the invasive front. The two pictures are from different sections of two patients. Bar 50 μm (A). The MOD value in tumor center was lower than that in invasive front (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, P = 0.022) (B). The Bland–Altman plot showed that the difference between tumor center and invasive front increased along with the average staining intensity (C)

Expression of CD44v6 mRNA in different sampling site

To further test the sampling bias in CD44v6 analysis, quantitative real-time PCR was conducted with samples from different site of the tumor (Fig. 5A). The differences of mRNA expression levels between a1 and a2 were from the stochastic error of PCR analysis, and the differences between a1 and b or a2 and b were from the stochastic error combined with different sampling sites. Data showed that there were no differences in relative fold changes between a1, a2, and b, but the differences between a1 and b or a2 and b were significantly higher compared with that between a1 and a2 (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, P = 0.012 and P = 0.027) (Fig. 5B, C), suggesting that the sampling bias may substantially affect the outcome of CD44v6-related studies.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis for CD44v6 in tissues from different sampling sites. The sampling strategy was illustrated (A). No differences in relative fold changes between a1, a2, and b was revealed (B). The differences between a1 and b or a2 and b were significantly higher compared with that between a1 and a2 (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, P = 0.012 and P = 0.027) (C)

Discussion

In this study, CD44v6 expression in the sequence of adjacent mucosa, primary rectal adenocarcinoma, and lymph node metastasis was investigated with whole tissue sections. And its association with clinicopathologic features including lymph node metastasis was analyzed. Our data demonstrated that the overall CD44v6 expression intensity successively increased in the order of normal mucosa, primary tumor and lymph node metastasis, implicating a potential role of CD44v6 in carcinogenesis and metastatic progression though no association with lymph node metastasis was revealed. It is supported by many investigators that up-regulation of CD44v6 occurs in early colorectal adenomas and involves in the adenoma-to-carcinoma progression [7, 8, 14]. However, the relationship between primary tumor and matched metastatic site is inconsistent. On one hand, increased immunoreactivity has been observed in lymph node metastasis which associated with adverse prognosis [15, 16]. On the other hand, decreased positivity has been reported in liver metastases while others found no differences between primary tumor and metastasis [6–8, 17]. A dynamic process of gain or loss of CD44v6 expression is assumed during metastatic seeding as indicated by the outliers in the correlation analysis, and thus affecting the outcomes of different studies.

In primary tumor, expression of CD44v6 presented multiple intratumoral staining patterns. As to subcellular localization, both membranous and cytoplasmic CD44v6 expression was observed in most sections which was difficult to be evaluated separately. CD44v6 is known as a multifunctional transmembrane adhesion molecule that closely interacted with the microenvironment [18]. Loss of membranous expression is associated with adverse patient outcome in several studies since lack of adhesive functions promote tumor cell scattering [6, 7, 19]. The biological role of cytoplasmic localization is rather unaddressed. Coppola et al. reported that cytoplasmic CD44v6 expression progressively increased while membranous expression decreased from adenoma to carcinoma to liver metastasis [14]. Zlobec et al. found that cytoplasmic expression was positively correlated with the membranous one, but no association with tumor progression or patient survival was revealed [6]. Avoranta et al. found that only cytoplasmic expression was affected by preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer [19]. And our previous study showed that CD44v6 protein can automatically localized to the membrane without additional signal peptide coding sequence after overexpression through lentiviral transduction in sw480 cells. Therefore, the protein in the cytoplasm is probably a precursor or recycled component of the functional CD44v6 which cannot be neglected. Herein, we revealed a new pattern that localized polarly in the apical membranous portion of the lumen, often coupled with positive staining in the glandular lumen, suggesting the protein might be downregulated via exocrine secretion.

Moreover, our analyses showed that CD44v6 expression in invasive front was significantly higher than that in tumor center, contrary to some previous publications [6, 7]. The discrepancy may originate from the intratumoral heterogeneity itself; because neither “front-positive” nor “front-negative” pattern exerted a dominant role hence the result may be inversed in different cohorts. CD44v6 is engaged in matrix assembly and crosstalk with many factors from the microenvironment, such as hepatocyte growth factor, osteopontin, and matrix metalloproteinases [20–22]. So, CD44v6 in the invasive front is more likely to be fast changing and play an active role during tumor progression. Further studies are required to elucidate the biological significances in tumor center or invasive front. However, the discordance between the two compartments indicated that quantitation for CD44v6 in a localized region like tissue microarray analysis may be misleading, as it differed between different geographical regions. In addition, results from quantitative real-time PCR analysis further verified our speculation that bias from different sampling sites impact the final consequence of individual studies. In such cases, the presence of CD44v6 in stromal cells or noncancerous cells should also be concerned when using approaches based on the average expression levels across the whole tissue, such as quantitative real-time PCR, genomic sequencing, and Western blotting analysis.

In summary, this study demonstrated that the overall CD44v6 expression progressively increased from normal mucosa to primary carcinoma to lymph node metastasis. The substantial intratumoral heterogeneity of CD44v6 exists in rectal cancer which has different subcellular localization patterns and differs between different geographical regions. And thus impact the outcome of individual studies. A possible solution is to assess CD44v6 expression in a designated location of a tumor with a specified subcellular staining pattern.

References

Zoller M. CD44: can a cancer-initiating cell profit from an abundantly expressed molecule? Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(4):254–67. doi:10.1038/nrc3023.

Ni J, Cozzi PJ, Hao JL, Beretov J, Chang L, Duan W, et al. CD44 variant 6 is associated with prostate cancer metastasis and chemo-/radioresistance. Prostate. 2014;74(6):602–17. doi:10.1002/pros.22775.

Saito S, Okabe H, Watanabe M, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, Baba Y, et al. CD44v6 expression is related to mesenchymal phenotype and poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(4):1570–8. doi:10.3892/or.2013.2273.

Todaro M, Gaggianesi M, Catalano V, Benfante A, Iovino F, Biffoni M, et al. CD44v6 is a marker of constitutive and reprogrammed cancer stem cells driving colon cancer metastasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(3):342–56. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.009.

Bendardaf R, Elzagheid A, Lamlum H, Ristamaki R, Collan Y, Pyrhonen S. E-cadherin, CD44 s and CD44v6 correlate with tumour differentiation in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2005;13(5):831–5.

Zlobec I, Gunthert U, Tornillo L, Iezzi G, Baumhoer D, Terracciano L, et al. Systematic assessment of the prognostic impact of membranous CD44v6 protein expression in colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 2009;55(5):564–75. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03421.x.

Wang L, Liu Q, Lin D, Lai M. CD44v6 down-regulation is an independent prognostic factor for poor outcome of colorectal carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(11):14283–93.

Afify A, Durbin-Johnson B, Virdi A, Jess H. The expression of CD44v6 in colon: from normal to malignant. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2016;20:19–23. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2015.10.010.

Burrell RA, McGranahan N, Bartek J, Swanton C. The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature. 2013;501(7467):338–45. doi:10.1038/nature12625.

Bedard PL, Hansen AR, Ratain MJ, Siu LL. Tumour heterogeneity in the clinic. Nature. 2013;501(7467):355–64. doi:10.1038/nature12627.

Fisher R, Pusztai L, Swanton C. Cancer heterogeneity: implications for targeted therapeutics. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(3):479–85. doi:10.1038/bjc.2012.581.

Lv L, Liu HG, Dong SY, Yang F, Wang QX, Guo GL, et al. Upregulation of CD44v6 contributes to acquired chemoresistance via the modulation of autophagy in colon cancer SW480 cells. Tumour Biol. 2016;. doi:10.1007/s13277-015-4755-6.

de Kok JB, Roelofs RW, Giesendorf BA, Pennings JL, Waas ET, Feuth T, et al. Normalization of gene expression measurements in tumor tissues: comparison of 13 endogenous control genes. Lab Invest. 2005;85(1):154–9. doi:10.1038/labinvest.3700208.

Coppola D, Hyacinthe M, Fu L, Cantor AB, Karl R, Marcet J, et al. CD44V6 expression in human colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(6):627–35.

Finke LH, Terpe HJ, Zorb C, Haensch W, Schlag PM. Colorectal cancer prognosis and expression of exon-v6-containing CD44 proteins. Lancet. 1995;345(8949):583.

Peng J, Lu JJ, Zhu J, Xu Y, Lu H, Lian P, et al. Prediction of treatment outcome by CD44v6 after total mesorectal excision in locally advanced rectal cancer. Cancer J. 2008;14(1):54–61. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181629a67.

Weg-Remers S, Anders M, von Lampe B, Riecken EO, Schuder G, Feifel G, et al. Decreased expression of CD44 splicing variants in advanced colorectal carcinomas. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(10):1607–11.

Ponta H, Sherman L, Herrlich PA. CD44: from adhesion molecules to signalling regulators. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(1):33–45. doi:10.1038/nrm1004.

Avoranta ST, Korkeila EA, Syrjanen KJ, Pyrhonen SO, Sundstrom JT. Lack of CD44 variant 6 expression in rectal cancer invasive front associates with early recurrence. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(33):4549–56. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i33.4549.

Huang J, Pan C, Hu H, Zheng S, Ding L. Osteopontin-enhanced hepatic metastasis of colorectal cancer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47901. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047901.

Damm S, Koefinger P, Stefan M, Wels C, Mehes G, Richtig E, et al. HGF-promoted motility in primary human melanocytes depends on CD44v6 regulated via NF-kappa B, Egr-1, and C/EBP-beta. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(7):1893–903. doi:10.1038/jid.2010.45.

Klingbeil P, Marhaba R, Jung T, Kirmse R, Ludwig T, Zoller M. CD44 variant isoforms promote metastasis formation by a tumor cell-matrix cross-talk that supports adhesion and apoptosis resistance. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7(2):168–79. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0207.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Science Foundation from the Health Bureau of Wenzhou City of Zhejiang, China (Y20140713) and by the Incubation Program from The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (FHY2014013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the clinical ethical committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Zhejiang, China (No. 2014055). All the specimens were obtained after written informed consent. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, HG., Lv, L. & Shen, H. Intratumoral heterogeneity of CD44v6 in rectal cancer. Clin Transl Oncol 19, 425–431 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-016-1542-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-016-1542-9