Abstract

Mucosal melanomas account for less than 1% of all sinonasal malignancies and are aggressive tumours originating from melanocytes in various mucosal epithelia. Diagnosis is often delayed due to nonspecific symptoms, contributing to challenges in treatment and management. We present a case of a 75-year-old female with epistaxis and nasal blockage, ultimately diagnosed with amelanotic sinonasal melanoma. Despite diagnostic difficulties exacerbated by profuse bleeding during biopsy attempts, a comprehensive approach involving clinical evaluation, imaging, and histopathology led to a definitive diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry played a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis, ruling out differential diagnoses such as olfactory neuroblastoma and lymphoma. Surgical excision, despite intraoperative bleeding, was successful, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy due to the tumor’s advanced stage. The case underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach and personalized treatment strategies, considering the tumor’s molecular characteristics for improved outcomes in managing this rare malignancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mucosal melanomas are rare and aggressive malignant tumours that originate from melanocytes in the mucosa of the nasal, oral, reproductive, and gastrointestinal epithelia. Mucosal melanomas in the paranasal sinuses account for less than 1% of all sinonasal malignancies. These malignancies, which were first identified in 1869, emerge slowly and represent a diagnostic challenge because of ambiguous early signs, contributing to an average age of diagnosis of 60–70 years. With a poor prognosis marked by significant recurrence (23–50%) and metastatic rates, early identification remains difficult [1].

Treatment modalities, including surgical excision, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, aim to combat these challenges. However, effective treatment requires precise diagnosis and staging with comprehensive imaging and histopathologic study. This emphasises the need of reliable diagnostic techniques in selecting effective therapeutic solutions. The presented case likely exemplifies the complex diagnostic and therapeutic landscape associated with mucosal melanomas, emphasising the importance of a holistic strategy to improving outcomes for patients dealing with this formidable malignancy [2].

Case Report

The patient, a 75-year-old female presented with a one-month history of epistaxis, right-sided nasal blockage, and a mass in the right nasal cavity. Notably, she had no history of trauma, recurrent epistaxis, postnasal drip, or use of anticoagulant medications. A local hospital referral led to her admission to our hospital, where she received oral antibiotics and nasal decongestants. Attempts to biopsy the right nasal mass were hampered by profuse bleeding, necessitating chemical cauterization.

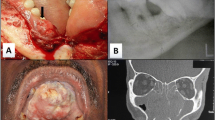

In terms of medical history, the patient had been hypertensive for one month, using tablet Amlodipine 5 mg once a day, and had no history of diabetes, TB, asthma, or previous surgeries. Clinical examination was within normal limits. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy revealed an occlusive erythematous mass in the right nasal cavity with associated bleeding and destruction of the septum and cribriform plate. (Fig. 1) The patient exhibited a deviated nasal septum to the left and hypertrophy of the right inferior turbinate.

An enlarged right upper jugulo-digastric lymph node was also discovered, however there were no abnormalities in the oral cavity or ears. The facial nerve investigation confirmed that both sides functioned normally. The NCCT PNS revealed a significant soft tissue density polyp in the right maxillary antrum, nostril, and extending into the ethmoidal sinus, indicating an antro-choanal polyp, pansinusitis, a blocked ostio-meatal unit, chronic rhinitis with turbinate hypertrophy, and a deviated nasal septum. (Fig. 2) The lamina papyracea and medial wall of the right maxillary sinus were displaced by the lytic lesion. Differentials were inverted papilloma, sinonasal malignancy, and invasive fungal sinusitis.

Further investigations included FNAC from a cervical lymph node, which revealed a monotonous population of tumor cells arranged in singly dispersed pattern. These cells had scant cytoplasm, granular chromatin with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 3). These features prompted a diagnosis of a small round blue cell tumour with differentials of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Metastatic Olfactory Neuroblastoma & Metastatic melanoma, prompting biopsy for further evaluation. The patient’s management involved excision and biopsy under general anaesthesia, where bleeding was noted intraoperatively but successfully controlled, leading to an uneventful postoperative recovery. Post-biopsy histopathological examination showed a lobular pattern of tumour cells arranged in nests & sheets in a background of extensive necrosis. The tumour cells showed moderate cytoplasm, pleomorphic vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli with increased mitoses (Fig. 4). A diagnosis of poorly differentiated malignant tumour was made with a recommendation to perform immunohistochemistry for further subtyping. Immunostaining on the biopsy sample showed S-100 & Melan-A positivity, NSE was patchy positive, CD56 was positive while CK, CD45, Synaptophysin, Chromogranin & Calretinin were negative (Fig. 5). Considering all the findings mentioned above, a diagnosis of Sinonasal Mucosal Melanoma (Amelanotic) with a staging of T4b N1 M0 (Stage IVb) was made. Post confirmation of diagnosis and keeping in mind the extent & inoperability of the lesion, Patient was counselled and referred for Chemotherapy & Radiotherapy. Patient was started on combination therapy with nivolumab (1 mg/kg) and ipilimumab(3 mg/kg).

A: Extensive necrosis with islands & nests of tumor cells [H&E; 40X] B: Lobulated pattern of tumor cells intervened by loose fibrovascular stroma [H&E; 40X] C: Peritheliomatous arrangement of tumor cells [H&E; 400X] D: Tumor cells showing pleomorphic vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli (black arrow), mitoses (red arrow) [H&E; 400X]

Discussion

Primary mucosal melanoma in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Delayed diagnosis is common, characterised by nonspecific symptoms such as unilateral nasal obstruction and epistaxis. Tumours can have a variety of hues and surface characteristics, ranging from slate to black, and an ulcerated look is common. Achromic melanomas, which lack pigmentation, account for around one-third of instances. Localization is primarily limited to the nasal septum and lateral wall or paranasal sinuses, notably the maxillary sinus [4].

The diagnosis requires a biopsy with immunohistochemistry as the interpretation by histology alone is limited due to absence of intracytoplasmic pigment [5]. Mucosal melanomas show varied cytomorphology ranging from epithelioid/undifferentiated cells to spindled, plasmacytoid, and rhabdoid cells, with or without prominent nucleoli. Diagnosis poses challenges in undifferentiated types (one-third of the cases) due to the wide range of histological differentials that may have similar morphological features. These include sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, olfactory neuroblastoma, nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma, mucosal melanoma & small cell undifferentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma [6]. Thus Immunohistochemistry plays a pivotal role in diagnosing these tumours. A panel of immunohistochemical markers is required: positivity for S-100, melanocytic markers (Melan-A, HMB45, tyrosinase, MITF) to confirm the diagnosis along with negativity for CK; CD45; Synaptophysin & Chromogranin; Calretinin & NSE to rule out sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, Lymphoma, small cell undifferentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma and olfactory neuroblastoma respectively, which was done in this case (Table 1). Mucosal melanomas have a worse prognosis compared to cutaneous melanoma [5].

Given the tumor’s poor prognosis, surgery is the primary therapeutic option, balancing tumour control with the patient’s quality of life. Endoscopic intranasal resection is appropriate for exclusively intranasal cancers, whereas external techniques such as craniofacial resection are used for more widespread malignancies, with a focus on large resection margins (1.5 to 2 cm negative margins). Systematic lymph node dissection is reserved for patients with clinically or radiologically abnormal lymph nodes [7, 8].

Radiation therapy is not highly effective in treating mucosal melanomas, and it is typically reserved for cases where the cancer has metastasized or for palliative care. When managing metastatic disease, treatment decisions are influenced by the presence of the BRAF V600 mutation. Vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, is specifically prescribed for patients who exhibit this mutation. Ipilimumab, alone or in conjunction with chemotherapy, is used for advanced, treatment-refractory forms in patients who do not have the BRAF V600 mutation. This personalised approach reflects advances in personalising treatments based on the tumour’s molecular characteristics, with the goal of improving outcomes in complex clinical circumstances [1].

Conclusion

Mucosal melanomas in the paranasal sinuses present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges due to their rarity and aggressive nature. This case highlights the complexities involved in diagnosing and managing these tumours, emphasizing the importance of a multidisciplinary approach for timely intervention. Despite the challenges encountered, successful surgical excision, combined with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, underscores the significance of diligent management in improving patient outcomes. The limited efficacy of conventional treatments underscores the need for personalized therapeutic strategies, considering molecular characteristics such as the BRAF V600 mutation. Further research is warranted to enhance our understanding of these rare malignancies and optimize treatment approaches for better patient care.

References

Gilain L, Houette A, Montalban A, Mom T, Saroul N (2014) Mucosal melanoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. European annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck diseases, vol 131. Elsevier Masson SAS, pp 365–369

Bridge JA, Bowen JM, Smith RB (2010) The small round blue cell tumors of the sinonasal area. Head Neck Pathol 4(1):84–93

Wenig BM (2008) Neoplasms of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Atlas of Head and Neck Pathology, Second edn. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 105–134

Thompson LDR (2017) Small round blue cell tumors of the sinonasal tract: a differential diagnosis approach. Mod Pathol 30(s1):S1–26

Meleti M, Leemans CR, de Bree R, Vescovi P, Sesenna E, van der Waal I (2008) Head and neck mucosal melanoma: experience with 42 patients, with emphasis on the role of postoperative radiotherapy. Head Neck 30(12):1543–1551

Williams MD (2017) Update from the 4th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck tumours: mucosal melanomas. Head Neck Pathol 11(1):110–117

Pratama YA, Praba IK, Herdini C, Indrasari SR, Yudistira D, Nina Y (2023) Amelanotic mucosal melanoma of the left sinonasal cavity: a case report. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 9(12):961–963

Verma R, Lokesh KP, Gupta K, Panda NK (2015) Sinonasal amelanotic malignant melanoma - A diagnostic dilemma. Egypt J Ear Nose Throat Allied Sci 16(3):275–278

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study has been carried out in compliance with the ethical standards after obtaining Institutional Ethics Committee Approval (Manipal Academy of higher Education- Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore)

Informed Consent

I hereby give my consent for images or other clinical information relating to my case to be reported in a medical publication. I understand that my name and initials will not be published and that efforts will be made to conceal my identity, but that anonymity cannot be guaranteed. I understand that the material may be published in a journal, web site or other form of publication. As a result, I understand the material may be seen by the general public. I understand that the material may be included in medical books.

Competing Interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Apoorva, K.V., Bhatia, S., Shenoy, S.V. et al. Amelanotic Melanoma: A Rare Sinonasal Malignancy. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-024-04837-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-024-04837-y