Abstract

This article deals with a rare occurrence of Ganglioneuroma of the left cervical sympathetic chain in a 9-year-old girl, presenting with painless paracervical swelling noticed since 7 months. Imaging studies showed a left parapharyngeal mass extending from C1 to C6, displacing the posterior pharyngeal wall and anterolaterally displacing the contents of the carotid sheath, with no significant vascular feeders. A provisional diagnosis of? Neurogenic tumour was established and the patient underwent surgical excision. Histopathologically, the diagnosis of Ganglioneuroma was confirmed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neurogenic tumours are a group of rare tumours that comprise of neuroblastomas, ganglioneuroblastomas and ganglioneuromas [1]. These tumours show different degrees of differentiation, where neuroblastomas are the least differentiated [2]. Ganglioneuromas are a well differentiated form of neuroblastomas, consisting of a fibrous matrix containing mature ganglion cells. It is difficult to distinguish between the different kinds of neuroblastic tumours, so tissue diagnosis is needed. Fine needle aspiration may not be accurate, because if the aspirate fails to target mature ganglion cells (diagnostic of neuroblastoma), it may suggest other malignant neurogenic tumours. The treatment of choice is Surgical excision [3].

Case Report

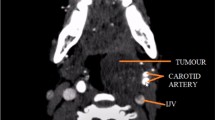

A 9-year-old girl presented to the Otorhinolaryngology outpatient department with history of an enlarging left paracervical mass noticed since 7 months, which was painless and not associated with any local or systemic signs of compression. The patient’s parents also gave history of snoring for 1 year. On examination, a diffuse fullness was noted over the left cervical region- non tender, firm, non-pulsatile, not fixed to underlying structures. Intraoral examination revealed a bulge in the left side of the posterior pharyngeal wall. During the investigations, CT showed a well-defined hypodense lesion extending to the left parapharyngeal space from C1 to C6. MRI done showed the lesion epicentred in the left prevertebral/ retropharyngeal space, hyperintense on T2WI, and isointense to muscles on T1 and not showing diffusion restriction. Anteriorly, the lesion displaced the posterior pharyngeal wall causing narrowing of the oropharyngeal lumen. Anterolaterally, it was seen to displace the contents of the carotid space, and laterally it indented the left sternocleidomastoid. A provisional diagnosis of? Neurogenic tumour? /? Haemangioma was established. To rule out a haemangioma, CT Angiography was done which showed no vascular feeders (Fig. 1) After preliminary investigations, the patient underwent complete surgical excision under general anaesthesia. A transcervical approach was used, after elevating skin flaps and retracting the sternocleidomastoid laterally to visualize the carotid sheath – a well encapsulated firm swelling was noted deep to the carotid sheath abutting the lateral pharyngeal wall and extending up to the skull base. Vagus, spinal accessory nerves and hypoglossal nerves were identified and preserved, the margins of the tumour were carefully dissected and the mass was dissected from the contents of the neck (Fig. 2). The attached nerve could not be separated from the tumour during excision. Post-operative period was unremarkable other than the occurrence of Horner’s syndrome on the left side. Gross examination of the tumor showed a nodular mass measuring 6.7 × 6 × 2.5 cm, with a smooth outer surface. Cut surface showed a well circumscribed, white solid mass with lobulations, firm in consistency. Microscopically, the tumour was encapsulated with bundles of nerve fibres criss-crossing each other in an irregular pattern interspaced with mature ganglion cells (Fig. 3). Areas of myxoid changes were seen. A pathological diagnosis of ganglioneuroma was established.

Discussion

Lorentz first described Ganglioneuromas in 1870, and De Quervain first reported them as occurring in the neck in 1899 [1]. Ganglioneuromas usually develop in childhood, however they are occasionally detected in adults owing to their slow growth. Two – thirds of patients with GNs are under the age of 20 years [4]. They are slow growing, well differentiated tumours of the autonomic nervous system. Usually they are asymptomatic, clinical manifestations are often local symptoms of compression but some patients may have diarrhoea, virilization, myasthenia gravis and hypertension. The lateral pharyngeal wall is compressed by expansion of the tumour, causing displacement of the tonsils and palatal arches. The patient may also present with dyspnoea, dysphagia and foreign body sensation. Patients may also present with Horner’s syndrome if the tumour originates from the cervical Sympathetic chain. Majority (60 – 80%) of Ganglioneuromas are located in the thoracic cavity, some (10 − 15%) are located in the abdominal cavity and few (5%)in the cervical region [5, 6]. Some uncommon locations include the middle ear, orbital space, parapharynx, skin, GIT [7,8,9].

MRI and CT are useful to determine the size, site and relationship of the tumour to surrounding structures. GNs are usually a well-defined oval mass, with low or intermediate CT attenuation and a marked high intensity signal on T2WI. PET scans may contribute to early diagnosis, as the lack of specific signs and symptoms make it harder to confirm the presence of a ganglioneuroma before pathological examination [10].

A neck swelling can have varied differentials like infectious cervical lymphadenopathy, branchial cleft cyst, malignancies such as other forms of neuroblastic tumours, NHL. However, the possibility of a ganglioneuroma must be taken into consideration even if it is rare [6].

In most cases, surgical excision was considered the best treatment modality. Rarely, such as in our case, excision of the cervical GN caused post-operative Horner’s syndrome resulting from disruption of the sympathetic innervation at different levels. The prognosis depends on the mechanism of injury [10]. Radiation therapy is usually avoided in view of young age of patients and uncertain results, combined with the possibility of radiation induced side effects such as growth retardation, radiation induced neoplasms [11]. After surgical excision, the lesion is sent for pathological examination to confirm the diagnosis. The gross appearance of a GN is a well encapsulated tumour which appears mucinous on sectioning. Microscopic examination reveals mature ganglion cells, and a cytological architecture consistent with mature ganglion cells with a lack of structural organization. Less well differentiated structures such as small basophilic cells are seen in more aggressive neurogenic tumours. Debulking is indicated if complete surgical excision is not possible. In majority of patients with incomplete resections, residual tumour does not usually regrow or produce symptoms [1]. Since GNs have no metastatic potential, prognosis is generally favourable [6].

References

Kaufman MR, Rhee JS, Fliegelman LJ, Costantino PD (2001) Ganglioneuroma of the parapharyngeal space in a pediatric patient. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg 124(6). https://doi.org/10.1067/mhn.2001.115371

Joshi VV, Cantor AB, Altshuler G et al (1992) Recommendations for modification of terminology of neuroblastic tumors and prognostic significance of Shimada classification. A clinicopathologic study of 213 cases from the pediatric oncology group. Cancer 69(8). https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19920415)69:<2183::AID-CNCR2820690828>3.0.CO;2-C

McCrory D, Kelly A, Korda M (2020) Postoperative Horner’s syndrome following excision of incidental cervical ganglioneuroma during hemithyroidectomy and parathyroid gland exploration. BMJ Case Rep 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2019-231514

Alimoglu O, Caliskan M, Acar A, Hasbahceci M, Canbak T, Bas G (2012) Laparoscopic excision of a retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma. J Soc Laparoendosc Surg 16(4). https://doi.org/10.4293/108680812X13517013316799

Albonico G, Pellegrino G, Maisano M, Kardon DE (2001) Ganglioneuroma of parapharyngeal region. Arch Pathol Lab Med 125(9). https://doi.org/10.5858/2001-125-1217-gopr

Califano L, Zupi A, Mangone GM, Long F (2001) Cervical ganglioneuroma: report of a case. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg 124(1). https://doi.org/10.1067/mhn.2001.111370

Wallace CA, Hallman JR, Sangueza OP (2003) Primary cutaneous ganglioneuroma: a report of two cases and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol 25(3). https://doi.org/10.1097/00000372-200306000-00008

Ozluoglu LN, Yilmaz I, Cagici CA, Bal N, Erdogan B (2007) Ganglioneuroma of the internal auditory canal: a case report. Audiol Neurotol 12(3). https://doi.org/10.1159/000099018

Cannon TC, Brown HH, Hughes BM, Wenger AN, Flynn SB, Westfall CT (2004) Orbital Ganglioneuroma in a patient with chronic Progressive proptosis. Arch Ophthalmol 122(11). https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.122.11.1712

Xu T, Zhu W, Wang P (2019) Cervical ganglioneuroma: a case report and review of the literature. Med (United States) 98(15). https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015203

Cushing BA, Slovis TL, Philippart AI et al (1982) A rational approach to cervical neuroblastoma. Cancer 50(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19820815)50:4<785::AID-CNCR2820500427>3.0.CO;2-P

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient and her family for their cooperation. The authors would also like to thank the faculty in the department of Otorhinolaryngology, Father Muller Medical College Hospital for their support and guidance.

Funding

There was no funding obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study complies with the ethical standards and ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee of Father Muller Medical College Hospital.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents prior to the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, T.T., Rao, V.V. Ganglioneuroma of the Cervical Sympathetic Chain - A Rare Occurrence. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 76, 1310–1313 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-023-04289-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-023-04289-w