Abstract

To document the clinical presentation, complications, management strategy and post-operative outcomes of extensive cholesteatomas. Cholesteatoma is a well demarcated cystic lesion derived from an abnormal growth of keratinizing squamous epithelium in the temporal bone. Cholesteatomas commonly involve the middle ear, epitympanum, mastoid antrum and air cells and can remain within these confines for a considerable period. Bony erosion is present confined to ossicular chain and scutum initially, but as the cholesteatoma expands, erosion of the otic capsule, fallopian canal and tegmen can occur. Erosion of the tegmen tymapani or tegmen mastoideum may lead to development of a brain hernia or cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Invasion of jugular bulb, sigmoid sinus, internal carotid artery are noticed in extensive cholesteatoma and are quite challenging and requires expertise. Neurosurgical intervention should be considered along with the otological management in the same sitting in all possible cases. A retrospective review of 12 patients were carried out to assess the clinical presentation, complications, surgical management and postoperative outcomes of extensive cholesteatomas presenting at our centre between January 2017 and December 2019. CT or MRI findings, extent of cholesteatoma intra-operatively along with the status of major neurovascular structures and disease clearance, and the post-operative outcomes including morbidity and mortality were noted. All patients underwent canal wall down mastoidectomy with or without ossiculoplasty. Post operatively all patients were treated with intravenous antibiotics and if required intravenous steroids. Amongst the 12 patients of extensive cholesteatoma (EC), all of them (100%) presented with foul smelling, purulent ear discharge. 9 (75%) patients presented with otalgia. 4 (33.33%) patients had temporal headache. 10 (83.33%) patients complained of hard of hearing. 7 (58.33%) patients gives history of vertigo at the time of presentation. In 8 (66.66%) patients there was tegmen plate erosion noticed in CT scan. In 3 (25%) patients, the disease was invading the sigmoid sinus and in 1 (8.33%) patient jugular bulb was involved. In 3 (25%) cases of EC, blind sac closure was performed. In two patients who developed cerebellar abscess, drainage procedure was performed. 2 (16.66%) patients developed sigmoid sinus thrombosis, 1 (8.33%) patient had petrositis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cholesteatoma is a well demarcated cystic lesion derived from an abnormal growth of keratinizing squamous epithelium in the temporal bone. They contain the desquamated debris from their keratinizing squamous epithelial lining. This abnormal growth is locally invasive and is capable of causing the destruction of structures in the middle ear cleft. Cholesteatomas commonly involve the middle ear, epitympanum, mastoid antrum and air cells and can remain within these confines for a considerable period. Bony erosion is present confined to ossicular chain and scutum initially, but as the cholesteatoma expands, erosion of the otic capsule, fallopian canal and tegmen can occur. This results in cholesteatomas to extend beyond the confines of the mastoid and temporal bone, causing intracranial complications, facial nerve, can extend medially to involve the bony labyrinth, or posterior fossa dura [1, 2]. Erosion of the tegmen tymapani or tegmen mastoideum may lead to development of a brain hernia or cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Invasion of jugular bulb, sigmoid sinus, internal carotid artery are noticed in extensive cholesteatoma and are quite challenging and requires expertise.

CT scan is useful to evaluate patients in whom there is a suspicion of otogenic brain abscess. It also aids in detecting the extent of disease, involvement of intracranial structures, elicit possible complications, and acts as a guide to the surgeon for pre-operative planning. MRI is much superior to CT scan in detecting subtle changes in the spread of abscess into subarachnoid space or into the ventricles.

Patients with extensive cholesteatoma present with foul smelling, creamy otorrhea. Otoscopic examination reveals an attic retraction with or without necrosis of ossicles. Post auricular swelling may indicate an impending mastoid abscess. Headache, high grade fever and focal neurological deficits indicate brain abscess [3, 4]. Focal deficits depend on the location of abscess. Cerebellar abscesses are characterized by dizziness, ataxia, nystagmus and vomiting. Signs of meningitis are occasionally present. Temporal lobe lesions may sometime provoke seizures.

The management of extensive cholesteatoma is a challenge as the disease may involve inner ear, internal carotid artery with or without extension into the intracranial structures. Patients are subjected to extensive mastoid exploration, canal wall down mastoidectomy. In cases of CSF otorrhea, Neurosurgical intervention may be required. Neurosurgical intervention should be considered along with the otological management in the same sitting in all possible cases.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review was carried out to assess the clinical presentation, complications, surgical management and postoperative outcomes of extensive cholesteatomas presenting at our centre between January 2017 and December 2019 after obtaining institutional ethical clearance. Inclusion criteria were chronic otitis media cases with extensive cholesteatoma with invasion of cochlea, destruction of semicircular canals and destruction of posterior wall of external auditory canal. 12 patients were identified who fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

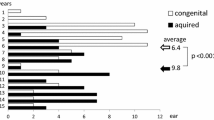

Presenting complaints/features, complications, CT or MRI findings, extent of cholesteatoma intra-operatively along with the status of major neurovascular structures and disease clearance, and the post-operative outcomes including morbidity and mortality were noted. Pre and post-operative audiological assessment was performed using pure tone audiometry with averages of hearing thresholds at 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz. Facial nerve grading in patients with facial palsy was carried out using the House–Brackmann system [5]. In these cases of facial palsy, EC was found to be encircling the facial nerve and the granulation tissue was removed meticulously. Post operatively patients were treated with intravenous administration of steroids and Physiotherapy.

All patients underwent canal wall down mastoidectomy with or without ossiculoplasty. Post operatively all patients were treated with intravenous antibiotics and if required intravenous steroids. All patients were followed up for period of 1 year. Any possible evidence of recurrence in the follow-up period was noted.

Results

Amongst the 12 patients of extensive cholesteatoma (EC), all of them (100%) presented with foul smelling, purulent ear discharge. The average duration of aural discharge was 3 years. 9 (75%) patients presented with otalgia. 4 (33.33%) patients had temporal headache. 10 (83.33%) patients complained of hard of hearing. 7 (58.33%) patients gives history of vertigo at the time of presentation as shown in Table 1. 6 (50%) patients had nystagmus on clinical examination. On otoscopic examination, all patients had attic retraction. In 5 (41.66%) patients, granulation tissue was visualised on otomicroscopy. One patient had Rhombergs sign positive in whom there was cerebellar abscess. PTA at the time of presentation showed an average of 55 dB hearing loss. 2 (16.66%) patients had associated sensorineural hearing loss with extensive cholesteatoma. In 8 (66.66%) patients there was tegmen plate erosion noticed in CT scan. In 3 (25%) patients, the disease was invading the sigmoid sinus and in 1 (8.33%) patient jugular bulb was involved. 10 patients were adults and two patients were children.

All patients underwent a canal wall-down mastoidectomy as a definitive procedure. Mastoid tip, retrofacial recess and posterior cavity were obliterated using fat and post auricular soft tissue which was lengthened. In two cases of EC invading the external auditory canal, blind sac closure was done. In one case of extensive cholesteatoma in cochlea, while drilling the cochlea CSF otorrhea was noticed and blind sac closure was done. Altogether in 3 (25%) cases of extensive cholesteatoma, blind sac closure was performed. In two patients who developed cerebellar abscess, drainage procedure was performed by a Neurosurgeon. The mastoid cavity exploration in this case was done and cleared off from cholesteatoma in the same sitting. In 7 (58.33%) patients of extensive cholesteatoma, ossciculoplasty was done following canal wall down mastoidectomy. Myringostapediopexy was done in two patients and myringoplatinopexy was done in five patients. In the remaining two cases, canal wall down mastoidectomy was performed without ossiculoplasty as they had associated sensorineural hearing loss (Table 2).

2 (16.66%) patients presented with pre-operative facial nerve palsy. Post surgery, 3 (25%) patients developed Grade 2 House Brackmann facial nerve palsy. In two patients, labyrinthine fistulae was present on lateral semi-circular canal and was addressed at the end of the surgery. The fistulae were covered with temporalis fascia graft. In 1 (8.33%) patient, labyrinthectomy was performed. 2 (16.66%) patients developed sigmoid sinus thrombosis, 2 (16.66%) patients presented with cerebellar abscess and 1 (8.33%) patient had petrositis [3, 6]. Decompression of the sigmoid sinus was done, but no anticoagulation therapy was used for patients with sigmoid sinus thrombosis. These patients were closely monitored. Patients with features of Gradenigo’s syndrome(petrositis) were treated with intravenous antibiotics and recovered.

Figures 1 and 2 depict the CT, Figs. 3 and 4 depict the intra-operative images of patients with extensive cholesteatomas (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Extensive cholesteatoma has been documented as the most frequent pathology responsible for intracranial complications of otitis media, and loss of bony barriers due to erosion by the disease as the most common pathway for intracranial extension [3, 6]. Intracranial complications of cholesteatoma and medially invasive cholesteatomas are a great challenge to diagnose and manage surgically. Urgent surgical management is of utmost importance in the form of treatment of intracranial complications with definitive canal wall-down mastoidectomy, performed at the earliest opportunity.

Management of brain abscesses through drainage procedures have been advocated either through burr hole craniotomies or through the transmastoid route. Hafidh et al. [4] performed mastoidectomy either before, during or 3–10 days following intracranial abscess drainage, depending on maturation of brain abscesses. Since most intracranial abscesses have an infective tract in continuity with the mastoid cavity, the selection of what route to be employed depends on the individual and institutional surgical protocols. But addressing both the intracranial abscess drainage along with mastoid exploration in the same sitting is advisable and the same was followed in our study.

In our study, 8/12 patients had significant erosion of the tegmen plate on CT scan. Five patients showed erosion of the tympanic or mastoid fallopian canal, as evidenced on CT and intraoperatively. Bony erosions in CT is characterized by the presence of scalloped margins. The bone eroding process first exposes the soft tissue of neighbouring structures. Protective granulations formed is the last line of defence. The pus under tension finally penetrates the wall of protective granulations by pressure necrosis. A prodromal period of partial or intermittent involvement of the structure frequently precedes the diffuse involvement. Thus, a milder, intermittent facial weakness may precede complete facial paralysis; recurrent mild vertigio may precede diffuse purulent labyrinthitis, and localized meningismus may precede diffuse purulent meningitis.

One patient of EC showed features of meningism like high grade fever, severe headache, vomiting. But once the patient was stabilized on treatment with intravenous antibiotics, the patient was taken up for canal wall down mastoidectomy. It is known that the incidence of intracranial complications is highest in the pediatric population [3, 6]. However in our study 2/12 cases of extensive cholesteatoma were children. The age of the children was below 10 years.

Sheehy and Brackmann [7] documented an incidence of 10% of labyrinthine fistulas in cholesteatoma cases. In our study, 2 (16.66%) patients had labyrinthine fistulae on lateral semi-circular canal and was addressed at the end of the surgery. The fistulae were covered with temporalis fascia graft. These patients presented with vertigo, hard of hearing, nystagmus and presence of granulation tissue on otomicroscopy.

2 (16.66%) patients presented with pre-operative facial nerve palsy. Post surgery, 3 (25%) patients developed Grade 2 House Brackmann facial nerve palsy. In these cases, EC was encircling the facial nerve and the granulation tissue was removed meticulously. Post operatively, on intravenous administration of steroids and Physiotherapy, weakness subsided in 3–4 months duration. Greenberg and Manolidis [8] described extensive facial nerve involvement by cholesteatoma as adherence of matrix to at least 10 mm of epineurium involving half or more of its circumference. The direct inflammatory involvement of the facial nerve through fallopian canal dehiscence and compression result in edema. Some believe that the cholesteatoma itself could cause facial paralysis through neurotoxic substances that it might secrete and or cause bony destruction via various enzymatic activities [9].

It has been documented that the widespread use of intravenous antibiotics has led to a significant decrease in the number of intracranial complications of otitis media with extensive cholesteatoma, with the incidence being much higher in developing countries than developed ones. Also, all our patients with intracranial complications belonged to low socio economic strata. In few studies, the use of corticosteroids significantly reduced the mortality, severe hearing loss and neurologic sequele associated with acute bacterial meningitis.

The requirements for a pathologic diagnosis of cholesteatoma include a combination of squamous epithelium, granulation tissue and keratinaceous debris. In all the 12 patients, the tissue histopathology showed cholesteatoma.

Conclusion

Extensive cholesteatomas are characterized by extension of the disease to inner ear, facial nerve and posterior fossa dural plate, along with the associated intracranial complications leading to significant morbidity and mortality, Development of complication in antibiotic era is not uncommon. Methodical evaluation with proper history taking, clinical examination, using imaging modalities like HRCT temporal bone, CT scan of brain to know the extent of disease and its complication is of utmost importance. Timely surgical management along with medical treatment is essential. Extensive cholesteatoma involves the middle ear with or without extension into the inner ear and intracranium. So canal wall down mastoidectomy is the surgical procedure of choice with Neurosurgical intervention done at the earliest in the same sitting preferably.

References

Bartels LJ (1991) Facial nerve and medially invasive petrous bone cholesteatomas. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 100:308–316

Grayeli AB, Mosnier I, El Garem H, Bouccara D, Sterkers O (2000) Extensive intratemporal cholesteatoma: surgical strategy. Am J Otol 21:774–781

Penido Nde O, Borin A, Iha LC, Suguri VM, Onishi E, Fukuda Y, Cruz OL (2005) Intracranial complications of otitis media: 15 years of experience in 33 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 132:37–42

Hafidh MA, Keogh I, Walsh RM, Walsh M, Rawluk D (2006) Otogenic intracranial complications. A 7-year retrospective review. Am J Otolaryngol 27:390–395

House JW, Brackmann DE (1989) Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 93:146–147

Ropposch T, Nemetz U, Braun EM, Lackner A, Tomazic PV, Walch C (2011) Management of otogenic sigmoid sinus thrombosis. Otol Neurotol 32:1120–1123

Sheehy JL, Brackmann DL (1979) Cholesteatoma surgery: management of labyrinthine fistula—a report of 97 cases. Laryngoscope 89:78–87

Greenberg JS, Manolidis S (2001) High incidence of complications encountered in chronic otitis media surgery in a U.S. metropolitan public hospital. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125:623–627

Chu FW, Jackler RK (1988) Anterior epitympanic cholesteatoma with facial paralysis: a characteristic growth pattern. Laryngoscope 98(3):274–279

Funding

No financial support or funding was taken for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

Study was conducted after obtaining Institutional ethical clearance.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prasad, K.C., Vyshnavi, V., Abhilasha, K. et al. Extensive Cholesteatomas: Presentation, Complications and Management Strategy. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 74 (Suppl 1), 184–189 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-020-01948-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-020-01948-0