Abstract

To improve business performance in rapidly changing environments, supply chain agility can be a crucial requisite to address responsiveness issues, especially in environments with high levels of customization. This paper examines the effect of supply chain agility on customer service, differentiation, and business performance. A survey research methodology was employed using a sample of 156 manufacturing firms that provide high levels of customization. In particular, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to evaluate the proposed model. The results suggest that supply chain agility influences customer service and differentiation positively. However, it does not affect business performance directly; instead, better business performance can be achieved and mediated through improved customer service and differentiation. In particular, differentiation through customer service is the most effective way to improve business performance, and supply chain agility can help to achieve high-level customer service. The paper advises managers on details of how to fulfil their business performance ambitions better through suggested key agile supply chain management activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Sustained success in manufacturing industries is often predicated on the capability to innovate, engender new ideas, and introduce new products frequently. Global competition has created a competitive market environment where it is difficult to increase sales with existing products. Growth in sales and the market share is increasingly dependent on the capability of a manufacturer to stimulate an existing market or penetrate a different one by offering new products and services. Consequently, new product introduction has become more rapid (Fisher and Ittner 1999), and for innovative products in particular, manufacturing systems have to be more flexible and agile (Fisher and Ittner 1999; Meyr 2004; Hu et al. 2011). Moreover, product proliferation and variety are increasing (Hu et al. 2011). For example, product differentiation has gone beyond the simple and prosaic categories of size, warranty, and gender to include regional and cultural tastes and personal lifestyle. In addition, differentiation requires considering diverse dimensions, such as product, customer service, technology, and marketing differentiation (Kim 2006).

Supply chain (SC) agility is a requisite capability mitigating the trade-off between product variety (e.g., frequent new product introduction) and SC performance in high-level customization environments (see Stavrulaki and Davis 2010). In addition, the connection between market winners/ qualifiers and lean/agile is generally accepted (Aitken and Towill 2002; Agarwal et al. 2006). At its simplest, the lean paradigm that typically employs a low level of customization is most suitable when the market-winning criterion is cost (i.e., cost leadership). However, when service and customer value enhancement (i.e., differentiation) are prime market-winning criteria with a high level of customization, then flexibility and agility become the critical acquisition (Mason et al. 2000). Stavrulaki and Davis (2010) emphasized the alignment between the key aspects of a product and its SC processes depending on four SC strategic foci (e.g., from build-to-stock to design-to-order), and highlighted the links between SC processes (e.g., production and logistics) and the SC strategy (e.g., lean, leagile, and agile). Matching the organizational focus with an appropriate SC strategy results in business benefits.

However, except in some extreme cases, such as highly standardized or customized industries, many organizations tend to employ a hybrid strategy, such as mass customization. They have attempted to capture both the economy of scale to improve cost efficiency and a high level of customization to improve customer service. Even efficiency-focused industries are often required to consider agility a market-winning or qualifying criterion to fulfill customer needs. Agility can help to reduce the total cost by shortening the lead time and reducing inventory. However, maintaining SC flexibility and agility remains a crucial requisite for managing product variety and innovation issues in high-level customization environments (see Agarwal et al. 2006; Stavrulaki and Davis 2010).

Based on the extent literature review, this study proposed to answer the following research questions: 1) What is the association between SC agility and business performance in real industries? How can business and financial performance be improved by agility in high-level customization environments? 2) What are the relationships between SC agility and other supporting strategic focuses in high-level customization environments, such as customer service and differentiation?

The development of a conceptual approach is proposed, suggesting a rapid responsiveness capability in a high-level customization context to improve business performance. In the proposed model, SC agility is suggested to support improved business performance, exploring the implications for SC management with two related strategic factors, customer service and differentiation. First, a distinct SC performance approach is required in high-level customization environments to manage product variety and innovation issues: SC agility. Second, two mediating factors are considered to improve business performance in high-level customization environments: customer service and differentiation. Finally, business performance is suggested as an ultimate organizational outcome.

A number of researchers (Goldman et al. 1995; Sharifi and Zhang 1999; Swafford et al. 2006) have investigated theoretical approaches to SC agility; however, the extant literature has not attempted to demonstrate the discrete procedures for achieving better business performance through the concept of agility. For example, although recent researchers (e.g., Tse et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2013; Chiang et al. 2016) investigated the direct relationship between agility and firm performance, conceptual links about how better business performance can be achieved by SC agility has not been explained. In addition, mediating strategic factors, such as customer service and differentiation, have not been empirically investigated within most types of highly customized industries that focus on an agile SC rather than lean SC strategy using cost leadership through economies of scale. Companies with different product types require different approaches and strategies. For example, Fisher (1997) suggested that products can be classified into two classes based on their demand patterns: functional or innovative. Products are classified as functional if they satisfy basic needs that do not change much over a period (i.e., a low level of customization). These types of product have stable, predictable demand with long product lifecycles, but lower profit margins, leading to focus on lean SC. Innovative products have high levels of innovation or fashion content and a higher profit margin, but a short lifecycle that results in highly unpredictable demand (i.e., a high level of customization), which leads to focusing on agile SC. Therefore, this study explored general relationships between SC agility and business performance by sampling diverse manufacturing industries that supply products with high levels of customization. The findings reveal general insights for SC managers by providing the empirical evidence they require in supporting their companies’ decision-making developments to achieve either innovation or product variety ambitions and improved business performance. Furthermore, the findings provide the appropriate theoretical approaches in a highly customized context.

The paper has the following structure. In the next section, a description of the literature review, conceptual model, and hypothesis development provide a theoretical background to the study. This is followed by a description of the research methodology. The next section consists of analyses and discussion of the research results, including the implications of the structural equation models employed to explore the relationships between SC agility and business performance. The final conclusions, study limitations, and suggestions for related future work bring the paper to a close.

2 Conceptual model and hypothesis development

2.1 SC agility

The agile concept implies the capacity to operate profitably in a competitive environment of continually and unpredictably changing customer opportunities. A flexible and rapid response represents an element of agility that was defined as the capability of an organization to adapt to or react to marketplace changes and exploit market opportunities (Goldman et al. 1995). Sharifi and Zhang (1999) have also defined agility as the ability to cope with unexpected challenges, to survive unprecedented threats of the business environment (i.e., sustainability), and to take advantage of changes as opportunities.

It is required to clearly distinguish between the concepts of flexibility and agility. Bernardes and Hanna (2009) clarified the conceptual differences between two terms that are often used inconsistently and ambiguously in operations management studies. They defined flexibility as the ability to change status within an existing configuration of pre-established parameters; alternatively, they considered agility the ability to rapidly reconfigure with a new parameter set at the business level. Thus, SC flexibility is concerned with the internally focused capability and adaptability of an organization’s internal supply chain functions, such as purchasing, engineering, manufacturing, and distribution. However, agility represents an externally focused competence and capability concentrating on speed at the business level; for example, market responsiveness, reduced product development cycle time, reduced delivery and manufacturing lead time, high levels of customization and service, and the frequency of product introduction (Swafford et al. 2008). SC agility represents how speedily these outcomes can be changed, and this study employs seven items to define supply chain agility based on the work of Swafford et al. (2008). To sum up, SC agility is regarded as an organization’s competitive capability (Ngai et al. 2011) to transform market uncertainty into opportunities through rapid response, especially in high-level customization environments.

According to Hallgren and Olhager (2009), three factors distinguish an agile from a lean manufacturing system: high customization capability, efficient variety handling, and frequent new product introduction. In addition, the choice of a cost-leadership strategy fully mediates the impact of the competitive intensity of an industry as a driver of lean manufacturing, whilst agile manufacturing is directly affected by two drivers: the differentiation strategy and the competitive intensity of the industry (Hallgren and Olhager 2009). An agile system is also found to be negatively associated with a cost-leadership strategy used in low-level customization environments, emphasizing the difference between lean and agile systems.

SC agility enables firms to improve their daily operations and customer service, which can result in differentiation and increasing profitability. Improving SC agility requires reducing the product development cycle and manufacturing and delivery lead time, increasing the level of product customization in manufacturing, and improving customer service, delivery reliability, and responsiveness to market needs (Sharifi and Zhang 1999; Van Hoek et al. 2001; Swafford et al. 2006; Swafford et al. 2008). SC agility is all about customer responsiveness and is essential in ensuring a firm’s external competitiveness (Van Hoek et al. 2001) that enables effective and efficient responses to operational changes, including procurement, manufacturing, and delivery (Liu et al. 2013). Therefore, SC agility focuses on customer responsiveness with speed influencing customer service and differentiation capabilities rather than cost leadership capabilities. Agility ensures responsiveness to customer requirements, services, resource efficiency and high business performance, and cost sensitivity to improve competitiveness, such as differentiation in volatile business environments (Hiroshi and David 1999; Agarwal et al. 2006). An agile SC is necessary to respond to volatile customer demand and high customer needs for product variety (Agarwal et al. 2006). Agile organizations can quickly satisfy customer orders, introduce new products frequently in a timely manner, and speedily achieve strategic alliance with their partners (Gligor and Holcomb 2012). Therefore, SC agility acts as a valuable operational capability, which is crucial to improving business performance (Swafford et al. 2008; Chiang et al. 2016). Tse et al. (2016) support the notion that SC agility positively influences firm performance. To sum up, rapid customer responsiveness in SCs can improve business performance by increasing opportunities in the market through enhanced customer service and differentiation. Therefore:

-

H1. SC agility is positively related to an organization’s customer service in a high-level customization environment.

-

H2. SC agility is positively related to an organization’s differentiation capability in a high-level customization environment.

-

H3. SC agility is positively related to an organization’s business performance in a high-level customization environment.

2.2 Customer service

The ultimate aim of SC management is to improve both efficiency (i.e., cost reduction) and effectiveness (i.e., customer service) in a strategic framework to obtain a competitive advantage and profitability (Mentzer et al. 2001). Therefore, customer service performance has been identified as a crucial component of a SC performance measurement system. Beamon (1998) also employed customer responsiveness as an output measure that sets goals for a high level of customer service. Customer service includes customer satisfaction, customer response times, on-time deliveries, order fill rates, minimizing customer complaints, backorder/stock-out, manufacturing lead time, and shipping errors (Beamon 1999). Therefore, the following eight items were defined as aspects of customer service in this study: 1) the fill rate, 2) on-time delivery, 3) customer response time, 4) quality, 5) manufacturing lead time, 6) customer complaint reduction, 7) customer satisfaction, and 8) stock-out reduction (Beamon 1999; Sezen 2008). Ramdas and Spekman (2000) also outlined six factors that reflect different approaches to measuring customer service outcomes as supply chain performance: inventory, time (e.g., product development time, time to market, and time to break even), order-fulfilment, quality, and customer focus and customer satisfaction.

As designed in this study customer service can be treated as an intermediate performance outcome, while financial performance is viewed as the final business performance outcome (Vickery et al. 2003). Customer service refers to the extent of customer responsiveness that results in sustaining a loyal customer base and expanding a new one (Narasimhan and Soo Wook 2002; Chan and Qi 2003; Otto and Kotzab 2003; Treville et al. 2004), which can improve business performance. In addition, customer-oriented SC performance (i.e., customer service) refers to the extent of an organization’s focus on its competitive advantage (i.e., differentiation) through the implementation of customer-oriented SC practices (Jeong and Hong 2007). Focusing on customer service measures can boost companies’ differentiation capability. Therefore:

-

H4. Customer service is positively related to an organization’s differentiation capability in a high-level customization environment.

-

H5. Customer service is positively related to an organization’s business performance in a high-level customization environment.

2.3 Differentiation strategy

A competitive strategy denotes how an organization can compete in a particular market. It is concerned with how a company can achieve a competitive advantage relative to its competitors. The aim is to establish a profitable and sustainable position for the company (Hallgren and Olhager 2009), which can impact a company’s business performance. First, cost leadership emphasizes cost reduction, and firms strive to become low-cost producers. Thus, efforts are focused on cost management so that above-average returns may be forthcoming even at low prices (Porter 1980; Kotha and Orne 1989). This strategy is prevalent in low-level customization environments. However, the rationale of differentiation is to avoid direct competition, e.g., cost leadership, by differentiating the products, services, and marketing offered to deliver higher customer value. Based on Miles and Snow’s (1978) theory, cost leadership priority is related to highly centralized organizational activities of the SC, whilst a differentiation priority is linked to highly specialized technological activities for new product development (NPD) and pioneering new market opportunities. This strategy is common in high-level customization environments.

The objective is to create products and services that are unique to customers (Kotha and Orne 1989), such as high quality and quick delivery. Kim (2006) divided the differentiation capability into three dimensions: focused customer service, innovative marketing technology, and product differentiation. Customer service is associated with quality, volume flexibility, and on-time delivery. Marketing differentiation, which was related to Porter’s focus strategy, is related to control sales and distribution. Lastly, product differentiation is related to NPD quickly with enough design flexibility. Hallgren and Olhager (2009) supported the concept that differentiation can involve the ability to change over products rapidly (i.e., product differentiation) or the ability to manage flexible volumes of products produced upon short notice (i.e., service differentiation). Thus, based on the classification by Kim (2006) and Hallgren and Olhager (2009), service (e.g., high quality with volume flexibility), product (e.g., new product development), and marketing differentiation (e.g., control of sales and distribution networks) were employed in this study as items to explain differentiation. The enhanced corporate competitive status acquired from a superior competition strategy, such as differentiation, has significant consequences for business performance (Miles and Snow 1978). Customer loyalty and repurchase intention as a result of differentiation strategy make it possible for the company to charge a premium price (Porter 1980), which also can boost business performance. Therefore:

-

H6. The differentiation capability is positively related to an organization’s business performance in a high-level customization environment.

2.4 Business performance

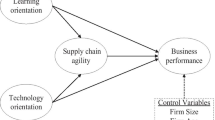

Business performance should be measured by accounting data that reveal a firm’s performance and the market valuation (Vickery et al. 2003). Vickery et al. (1999) employed the return on investment (ROI), return on sales (ROS), market share, and each performance’s growth (i.e., market share, ROI and ROS growth) as a business performance indicator. Sánchez and Pérez (2005) used ROI, ROS, market share, ROI growth, ROS growth, and market share growth. Similarly, Rosenzweig et al. (2003) employed four measures of business performance: ROA, sales growth, customer satisfaction, and % revenue from new products. Panayides (2007) argued that a composite measure of performance would reflect more accurately a firm’s improvements, as opposed to a single quantitative performance measure. Thus, ROS, ROA, market-share growth and sales growth were employed as observed variables for explaining business performance in this study. Figure 1 shows the research model. All measurement items for the constructs employed in this study were widely disseminated in relevant literature.

2.5 Customization

Early research by Lampel and Mintzberg (1996) illustrated the development of a customization framework composed of five strategies: pure standardization (PS), segmented standardization (SS), customized standardization (CS), tailored customization (TC), and pure customization (PC). The levels of customization increase from pure standardization to pure customization.

Agarwal et al. (2006) affirmed the necessity for a much higher level of agility given the volatile customer demand and high customer need for variety, suggesting market winning criteria and market qualifying criteria in three types of SCs: lean, agile, and leagile. According to Hallgren and Olhager (2009), three factors distinguish an agile from a lean system: a high customization capability, efficient variety handling, and new product agility. Baker (2008) also stated that agility is needed to cope with the demand uncertainty caused by seasonality, a short product lifecycle, and customer demand fluctuations, which are the main characteristics of high-level customization environments. Agility can help to reduce costs in low-level customization environments (Liu et al. 2013). However, agility is a more appropriate capability for innovative products in high-level customization environments (see Stavrulaki and Davis 2010) to provide better customer service. Therefore, a high-level customization environment requires agile SC and organizational strategies focusing on customer service and differentiation, while a low level of customization stresses cost efficiency and leadership strategies through the lean SC. In this research Lampel and Mintzberg’s (1996) classification was employed to capture the high-level customization concept that typically uses agile supply chain strategy through make-to-order (MTO) or design-to-order (DTO).

3 Methodology

3.1 Measures and data collection

For SC agility and customer service, respondents were asked to “indicate the company’s level of agreement” using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). Second, respondents were asked to “indicate how well the company performs in each of the following compared to competitors” in questions of differentiation on a Likert scale ranging from “poor” to “excellent.” Last, respondents were asked to “indicate how well the company performs” using a five-point Likert scale (1 = poor and 5 = excellent). Respondent were also asked to select their level of customization based on the Lampel and Mintzberg (1996) classification. Data were obtained from diverse manufacturers in both the U.K. and South Korea. Manufacturing companies were randomly selected, based on the standard industrial classification (SIC) code in the U.K. through the FAME database, and the final version of the questionnaire was sent to manufacturing companies by mail. In Korea, to obtain an acceptable level of response, e-mail and a structured interview survey were chosen. The questionnaires were sent to 1950 chief executive officers (CEOs), directors, managers, and staff of SC-related departments. By June 2012, 363 (211 U.K. and 152 South Korean) respondents had completed them by mail, e-mail, or face-to-face interviews, for a response rate of 19 %. The respondents were asked to choose a degree of customization, corresponding to pure standardization, segmented standardization, customized standardization, tailored customization, and pure customization (1 = PS and 5 = PC). The most commonly recognized measures were suitable for a small number of clusters with large data (Hair et al. 2010). K-means cluster analysis based on Euclidean distance was employed to assign the respondents into the most appropriate clusters according to the level of customization (i.e. low- or high-level customization). The mean for the high-level customization group was 4.43 (n = 156) and for the low-level customization group was 2.15 (n = 207). This research employed high-level customization group samples (i.e., UK = 102, Korea =54) based on the research framework that defines customization as five different levels (see Lampel and Mintzberg 1996). With regard to the total sample, 50.7 % of the firms were small and medium-sized (SMEs); and 49.3 % were large firms (LEs), based on the number of employees. A total of 88 % of respondents held positions above the senior management level, such as CEO, director, and manager.

To estimate the likelihood of non-response and late-response bias, t-tests were considered to compare characteristics between early and late respondents (Armstrong and Overton 1977). The comparison of sales and the number of employees revealed no statistical differences; thus, there was no non-response bias. To test for the probability of a common method bias, Harman’s one-factor test was applied. A principal components factor analysis was conducted on all items, resulting in the extraction of four constructs. These accounted for 62 % of total variance, and the first factor accounted for 19 % with eigenvalues above 1. As no single factor was apparent in the unrotated factor structure, common method bias was not an issue in this research. The result of a measurement invariance test indicated that data from the two countries did not suggest the presence of measurement bias (Milfont and Fischer 2010); therefore, the basic structure of the model is cross-culturally stable. The types of industry in the high-customization group are shown in Table 1.

3.2 Reliability and validity

Before testing the proposed model using structural equation modeling (SEM), the reliability and validity of model should be confirmed. Therefore, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to determine the composite reliability (CR) and the convergent and discriminant validity. Different fit indices for the model variables were examined using the AMOS 12.0 statistical package. Five items from the list of dependent and independent variables were removed since their loadings were lower than 0.7: three items from customer service (i.e., CS5, 6 and 8), one item from differentiation (i.e., D3), and one item from business performance (i.e., BP3). Reducing the number of construct indicators does not sacrifice content validity and can allow for more parsimonious analysis. Table 2 highlights factor loadings, CR, and the average variance extracted (AVE) with fit indices. The recommended maximum values for SRMR and RMSEA is 0.08 (Hair et al. 2010). The other three measures typically used—the comparative fit index (CFI), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and the non-normed fit index (NNFI)—all have recommended minimum thresholds of 0.90 (Hair et al. 2010; Kline 2011). In addition, Segars and Grover (1993) recommend the ratio of χ2 to the degrees of freedom as less than 3.0 to indicate a reasonable fit.

After deleting the redundant items, CFA was retested. The measurement model offered an acceptable fit to the data (χ2/df = 324.971/113 = 2.88; GFI = 0.905; SRMR =0.050; RMSEA =0.072; CFI = 0.930; NNFI =0.916). CR demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (CRs > 0.732). Therefore, convergent validity was guaranteed (loadings >0.7) with acceptable AVE (>0.541). No case existed in which the square of a correlation between constructs was greater than the AVE of the constructs (see Table 3). Therefore, discriminant validity was established, employing procedures suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981). In addition, agility shows close correlations with customer service (0.510) and differentiation (0.530). Table 3 shows correlations and AVEs for each construct with means and standard deviations.

4 Result of the SEM analysis

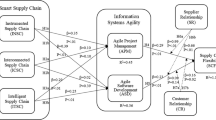

The empirical data demonstrated acceptable fits with the model, and the paths had high t-values (above 2.43) and acceptable p-values (below 0.05). GFI (0.890), CFI (0.949), RMSEA (0.061), and SRMR (0.041) indicated an acceptable fit with the model. All paths except the path between SC agility and business performance indicated positive relationships at the 0.001 significance level. Thus, the results supported the postulated hypotheses H1, H2, H4, H5, H6, and rejected H3. The model’s assumption that SC agility improves business performance through customer service and differentiation strategies was confirmed. In particular, SC agility has a stronger impact on customer service (i.e., 0.526) than agility on differentiation. Customer service has a positive impact on business performance directly (i.e., 0.409) or indirectly through differentiation (i.e., 0.364). However, SC agility has a negative impact on business performance directly at the 0.05 significance level. Figure 2 depicts the SEM diagram with path coefficients, levels of significance, and fit indices.

5 Discussion

This study considers SC agility in improving business performance. Focusing on SC agility in high-level customization environments is essential for improving business performance. However, an agile SC is not a direct solution to achieving excellent business performance. Instead, high-level customer service and differentiation strategies can mediate between SC agility and business performance. Since agility can incur initial set-up, investment, and operation costs using small batches for responding to customer requirements rapidly, a positive, direct relationship was not revealed between agility and business performance (i.e., path coefficient = − 0.302). This also can be explained by the incongruous relationship between agility and cost leadership (see Hallgren and Olhager 2009), and diseconomies of scale. However, improved customer service and differentiation capabilities achieved by SC agility can lead to improved business performance. To sum up, SC agility can boost business performance (Swafford et al. 2008; Chiang et al. 2016), not directly, but through improved customer service and differentiation capabilities. In addition, the model results demonstrated the notion that differentiation through customer service is the most effective way to improve business performance, and that SC agility can support organizations in achieving high-level customer service and differentiation capabilities. Thus, a firm with a high level of customer service and differentiation capability has the potential to achieve better business performance through SC agility.

The findings concerning H1 and H2 suggest that SC agility has a greater influence on both customer service and differentiation in a high-level customization context. In addition, high-level customer service leads to a differentiation position in the market (H4), resulting in increased business performance. For example, for companies providing highly customized products (i.e., innovative products) focusing on customer service, market responsiveness, and differentiation rather than cost leadership, improvements in SC agility are particularly important since agile SC is the winning criterion in the highly customized market. This finding also offers guidelines for the structural processes for manufacturing companies that tend to shift their strategy from cost leadership to a hybrid strategy (e.g., Ikea provides low cost with differentiation in product design and variety). Because of the different position of alignment between organizational (e.g., cost leadership and differentiation) and SC strategies (e.g., lean and agile) according to the degree of customization (Agarwal et al. 2006; Stavrulaki and Davis 2010), organizations’ capabilities, such as SC agility, customer service, and differentiation, should be evaluated to improve their business performance. Particularly in a high-level customization environment, although SC agility imposes cost burdens (see Hallgren and Olhager 2009), it has a positive impact on overall business performance (i.e., ROS, ROA, and sales growth) through improved customer service and differentiation capabilities.

This study is the primary empirical attempt to examine the impact of SC agility on different dimensions of performance, including customer service, differentiation, and business performance using a sample of 156 diverse manufacturing companies within a high-level customization environment. The study supports the strategic theories (Agarwal et al. 2006; Stavrulaki and Davis 2010) on relationships between SC agility and business performance by suggesting mediating concepts of customer service and differentiation. In addition, as a distinct concept of SC flexibility, the concept of SC agility was regarded as an external, business-level capability and competence to respond to customer needs in a speedy manner (see Swafford et al. 2008). Therefore, SC agility can be an effective means of achieving better customer service, differentiation, and business performance in high level customization environments.

This study offers several contributions. First, regarding the theoretical implications, it establishes a rich structure and process by which SC agility as an organizational competence influences business performance; importantly, the process is mediated by customer service and differentiation. Second, the study explains empirically the differential effects SC agility has on relationships between customer service, differentiation, and business performance. The distinctive operations characteristics and strategic focus in high-level customization environments supported the varied relationships.

Regarding managerial implications, the results support organizational decision making by providing managers with guidance on how best to improve business performance in SCs under highly competitive and customized market conditions. The main contribution of this work is its empiricism. Thus, the study provides empirical evidence to improve business performance, which is organizations’ ultimate goal, suggesting the significance of SC agility (i.e., 7 items), customer service (i.e., 8 items), and differentiation capabilities (i.e., three items). The findings in particular stress the importance of management’s alignment between their SC strategy and market position in a high-level customization context, and support the complex policymaking for manufacturers that are intending to provide high levels of product variety with high-level customization or are shifting their strategy from a low- to a high-level customization environment in the market to achieve better business performance.

6 Conclusion and limitations

Business performance ambitions for better competitiveness should be considered in terms of optimizing the strategic focus according to market needs and the capacity of manufacturers. In particular, achieving SC agility is an essential approach to enhance customer service and market position differentiation, especially in the context of a high level of customization (i.e., innovative product industry). The findings demonstrated that an agile SC improves business performance through increased customer service and differentiation rather than reducing the cost in a highly competitive and customized market. This study offers extended theoretical and managerial implications for adopting agile SC approaches to improve business performance by achieving customer service and differentiation in high-level customized environment.

The first limitation of this study relates to the methodology. Although competitive, environmental and cultural disparities exist among countries and regions (Hughes and Morgan 2008) this study focuses exclusively on manufacturing industries in two countries. For example, level of product variety can vary according to economic background (e.g., inequality), competition intensity (e.g., rivalry) or cultural preferences (e.g., product functions), which may decide the level of SC agility required to improve business performance. Second, various manufacturers’ data are examined to investigate general relationships between an agile supply chain and business performance, although hybrid strategies, such as cost leadership and differentiation strategies, rather than a single strategy might well occur. Last, to increase accuracy and reliability, financial measures (e.g., ROS, ROA) should be collected as a specific dataset through interview-based survey research or field-based case studies. Thus, case studies from different levels of customization should be employed to provide in-depth examinations and validate the extant results. A topic to be addressed in future research is the analysis of the impact of SC agility on business performance, including both cost efficiency and customer service (see Beamon 1999), by levels of customization.

References

Agarwal A, Shankar R, Tiwari MK (2006) Modeling the metrics of lean, agile and leagile supply chain: an ANP-based approach. Eur J Oper Res 173(1):211–225

Aitken JMC, Towill D (2002) Understanding, implementing and exploiting agility and leanness. Int J Logist 5(1):59–74

Armstrong JS, Overton TS (1977) Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J Mark Res 14(3):396–402

Baker P (2008) The design and operation of distribution centres within agile supply chains. Int J Prod Econ 111(1):27–41

Beamon BM (1998) Supply chain design and analysis: models and methods. Int J Prod Econ 55(3):281–294

Beamon BM (1999) Measuring supply chain performance. Int J Oper Prod Manag 19(3/4):275–292

Bernardes ES, Hanna MD (2009) A theoretical review of flexibility, agility and responsiveness in the operations management literature toward a conceptual definition of customer responsiveness. Int J Oper Prod Manag 29(2):30–53

Chan FTS, Qi HJ (2003) An innovative performance measurement method for supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag 8(3/4):209–223

Chiang CY, Hillmer C, Suresh N (2016) An empirical investigation of the impact of strategic sourcing and flexibility on firm’s supply chain agility. Int J Oper Prod Manag 32(1):49–78

Fisher ML (1997) What is the right supply chain for your product? Harv Bus Rev 75(2):105–116

Fisher ML, Ittner CD (1999) The impact of product variety on automobile assembly operations: empirical evidence and simulation analysis. Manag Sci 45(6):771–786

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Gligor DM, Holcomb MC (2012) Understanding the role of logistics capabilities in achieving supply chain agility: a systematic literature review. Supply Chain Manag 17(4):438–453

Goldman SL, Nagel RN, Preiss K (1995) Agile competitors and virtual organizations: strategies for enriching the customer. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York

Hair FJ, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2010) Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective. Pearson Education, New Jersey

Hallgren M, Olhager J (2009) Lean and agile manufacturing: external and internal drivers and performance outcomes. Int J Oper Prod Manag 29(10):976–999

Hiroshi K, David B (1999) Agility, adaptability and leanness: a comparison of concepts and a study of practice. Int J Prod Econ 60(3):43–51

Hu SJ, Ko J, Weyand L, ElMaraghy HA, Lien TK, Koren Y, Bley H, Chryssolouris G, Nasr N, Shpitalni M (2011) Assembly system design and operations for product variety. CIRP Ann Manuf Technol 60(2):715–733

Hughes P, Morgan RE (2008) Fitting strategic resources with product-market strategy: performance implications. J Bus Res 61(4):323–331

Jeong JS, Hong P (2007) Customer orientation and performance outcomes in supply chain management. J Enterp Inf Manag 20(5):578–594

Kim SW (2006) Effects of supply chain management practices, integration and competition capability on performance. J Supply Chain Manag 11(3):241–248

Kline RB (2011) Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. Guilford Press, New York

Kotha S, Orne D (1989) Generic manufacturing strategies: a conceptual synthesis. Strateg Manag J 10(3):211–231

Lampel J, Mintzberg H (1996) Customizing customization. Sloan Manage Rev 38(1):21–30

Liu H, Ke W, Wei K, Hua Z (2013) The impact of IT capabilities on firm performance: the mediating role of absorptive capacity and supply chain agility. Decis Support Syst 54:1452–1462

Mason JR, Naylor B, Towill DR (2000) Lean, agile or leagile? Matching your supply chain to the marketplace. Int J Prod Res 38(17):4061–4070

Mentzer JT, DeWitt W, Keebler JS, Min S, Nix NW, Smith CD, Zacharia ZG (2001) Defining supply chain management. J Bus Logist 22(2):1–26

Meyr H (2004) Supply chain planning in the German automotive industry. OR Spectr 26(4):447–470

Miles RE, Snow CC (1978) Organizational strategy, structure, and process. McGraw-Hill, New York

Milfont TL, Fischer R (2010) Testing measurement invariance across groups: applications in cross-cultural research. Int J Psychol Res 3(1):111–121

Narasimhan R, Soo Wook K (2002) Effect of supply chain integration on the relationship between diversification and performance: evidence from Japanese and Korean firms. J Oper Manag 20(3):303–323

Ngai EWT, Chau DCK, Chan TLA (2011) Information technology, operational, and management competencies for supply chain agility: findings from case studies. J Strateg Inf Syst 20(3):232–249

Otto A, Kotzab H (2003) Does supply chain management really pay? Six perspectives to measure the performance of managing a supply chain. Eur J Oper Res 144(2):306–320

Panayides PM (2007) The impact of organizational learning on relationship orientation, logistics service effectiveness and performance. Ind Mark Manag 36(1):68–80

Porter ME (1980) Competitive strategy: techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. Free Press, New York

Ramdas K, Spekman R (2000) Chain or shackles: understanding what drives supply-chain performance. Interfaces 30(4):3–21

Rosenzweig ED, Roth AV, Dean JW (2003) The influence of an integration strategy on competitive capabilities and business performance: an exploratory study of consumer products manufacturers. J Oper Manag 21(4):437–456

Sánchez AM, Pérez MP (2005) Supply chain flexibility and firm performance: a conceptual model and empirical study in the automotive industry. Int J Oper Prod Manag 25(7):681–700

Segars AH, Grover V (1993) Re-examining perceived ease of use and usefulness: a confirmatory factor analysis. MIS Q 17(4):517–525

Sezen B (2008) Relative effects of design, integration and information sharing on supply chain performance. Supply Chain Manag 13(3):233–240

Sharifi H, Zhang Z (1999) A methodology for achieving agility in manufacturing organisations: an introduction. Int J Prod Econ 62(2):7–22

Stavrulaki E, Davis M (2010) Aligning products with supply chain processes and strategy. Int J Logist Manag 21(1):127–151

Swafford PM, Ghosh S, Murthy N (2006) The antecedents of supply chain agility of a firm: scale development and model testing. J Oper Manag 24(2):170–188

Swafford PM, Ghosh S, Murthy N (2008) Achieving supply chain agility through IT integration and flexibility. Int J Prod Econ 116(2):288–297

Treville SD, Shapiro RD, Hameri AP (2004) From supply chain to demand chain: the role of lead time reduction in improving demand chain performance. J Oper Manag 21(6):613–627

Tse YK, Zhang M, Akhtar P, MacBryde F (2016) Embracing supply chain agility: an investigation in the electronics industry. J Supply Chain Manag 21(1):140–156

Van Hoek RI, Harrison A, Christopher M (2001) Measuring agile capabilities in the supply chain. Int J Oper Prod Manag 21(2):126–147

Vickery SK, Calantone R, Dröge C (1999) Supply chain flexibility: an empirical study. J Supply Chain Manag 35(3):16–24

Vickery SK, Jayaram J, Droge C, Calantone R (2003) The effects of an integrative supply chain strategy on customer service and financial performance: an analysis of direct versus indirect relationships. J Oper Manag 21(5):523–539

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Um, J. The impact of supply chain agility on business performance in a high level customization environment. Oper Manag Res 10, 10–19 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-016-0120-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-016-0120-1