Abstract

Ganglioneuroma is a benign, slow-growing neurogenic tumor arising from neural crest cells. It is extremely rare (1/1,000,000) and is located most commonly in the posterior mediastinum (41.5%), retroperitoneum (37.5%), and adrenal glands (21%). We present a case of a 62-year-old lady who had complaints of shortness of breath on exertion and dyspnea for the past 3 months. She had no other significant history. Computerised tomography (CT) scan of the thorax suggested left-sided loculated subpulmonic pleural effusion, 14 × 12 cm in dimension. She underwent assisted video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) exploration of the thorax with debridement and drainage of subpulmonic collection that was abutting the diaphragm, along with release of trapped lung. Histopathological examination showed multiple ruptured cystic masses with nodules; microscopical evidences of Schwann cells, ganglion cells, and spindle cells—all these along with immunohistochemistry—revealed features consistent with ganglioneuroma. Postoperative recovery was uneventful, and the patient did not have any complaints or other limitations to daily life activities at 6 months’ follow-up. Ganglioneuroma is essentially benign in nature, asymptomatic, and rare. A systematic review of the literature has shown that giant-sized ganglioneuromas (size more than 10 cm) have rarely been reported. Surgical excision and clearance is the treatment modality of choice. In our case, due to large size and difficulty in access and mobilisation of the mass adherent to the diaphragm, assisted VATS had to be performed. We increased the size of the utility port from 5 to 10 cm and used a rib retractor for better surgical negotiation. This could have been more challenging, as there have been incidences where ganglioneuromas have extended both into the thoracic and abdominal cavities and even involved vital organs and vessels. Regular follow-up is essential, as late recurrence and slow progression potential is a known complication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neuroblastic tumors are the most common solid tumor growing extracranially in childhood. They arise from neural crest cells. They include neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma. [1]

Ganglioneuroma is a benign, slow-growing neurogenic tumor composed of both mature stroma and gangliocytes. It is extremely rare (1/1,000,000) and arises from the sympathetic chain, located most commonly in the posterior mediastinum (41.5%), retroperitoneum (37.5%), adrenal glands (21%), and at times in the neck, retropharyngeally or more rarely in the sella turcica [2, 3]. It occurs more in females compared to males, with a ratio of about 3:2 [4]. It is most commonly seen in pediatric population, with 60% of total diagnoses done before the age of 20 years.

Incidence of large-sized (< 10 cm) ganglioneuroma is rare. A literature research was conducted by us for identifying all reported cases or possible existing case series or systematic reviews, describing such tumors presenting as subpulmonic effusion, using the MeSH terms < ganglioneuroma > , < effusion > , < pleural effusion > , and < empyema > on PubMed and Google Scholar. Ours is the first reported case of ganglioneuroma that presented unusually, with features of subpulmonic effusion.

This case report has been made according to CAse REports (CARE) checklist.

Patient information and clinical findings

A 62-year-old lady presented with complaints of shortness of breath on exertion and dyspnea for 3 months. Her comorbidities included hypertension, for which she was on medication. She had no prior history of any chest pain, palpitation, syncope, weight loss, fever, or any alteration in appetite and bowel habits. There was no history of trauma, malignancy, prior radiotherapy, or smoking. No other significant history was elicited.

General and systemic examination findings were unremarkable apart from dullness on percussion and reduced air entry on auscultation in the left lower zone of the chest.

Diagnostic assessment

Baseline laboratory investigations revealed no abnormalities. Inflammatory markers were within normal limits. Chest X-ray (posteroanterior (PA) and left lateral), done in erect posture, revealed an opacity, possibly signs of fluid accumulation in the base of the left lung (Fig. 1a, b). A computed tomography (CT) scan was done subsequently. It showed large, loculated pleural effusion in the left lower hemithorax. It measured 14 cm (craniocaudal) × 12 cm (anteroposterior). No evidence of pleural thickening was seen as such (Fig. 1c).

On evaluating clinical and radiological parameters, she was preliminarily diagnosed to have left-sided subpulmonic effusion. In view of large loculated collection, with a history of 3 months, surgical evacuation was preferred over thoracocentesis and other therapeutic options. The patient was worked up for operation and informed consent was taken.

Surgical procedure

The patient was planned to undergo video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) as is the institutional protocol for such cases. Left-sided assisted VATS thoracic exploration with excision and draining of subpulmonic loculated collection and debridement was done along with release of trapped lung.

A 5-cm utility incision was made in the 5th intercostal space (ICS) in the mid-axillary line (MAL). Another port, 2 cm in size, was made in MAL in the 8th ICS, under vision. The entire thoracic cavity was visualised, and adhesiolysis was done. Loculated collection was located by finger palpation and confirmed with needle aspiration and transillumination. Because of difficulty in mobilising and abutment to diaphragm, adding to the challenges caused by difficult anatomical location, the utility port was extended to 10 cm, thus converting to assisted VATS. The cyst wall was then opened and loculi broken. Collection was drained and thorough debridement done. The diaphragm was found to be intact, after removal of the collection, and found to be thin walled. Hemostasis was secured. One 32-Fr intercostal drain (ICD) was kept in situ. The left lung expanded on table with no air leak. Resected tissue (Fig. 2a) was sent for histopathological examination and microbiological investigations.

The thoracic cavity was closed in layers with no. 1 absorbable, synthetic polyglactin sutures. Subcutaneous tissue was closed with 1-0 absorbable polyglactin sutures while skin was closed with 2-0 nylon sutures and stapler.

Postoperative course and follow-up

The patient had an uneventful postoperative course. ICD was removed on 4th postoperative day (POD) after drain output of less than 100 ml for two consecutive days.

The resected tissue, sent for analysis, did not grow anything on Ziehl-Neelsen stain, acid fast bacilli culture, Gram stain, or culture sensitivity.

Histopathological examination revealed cystic lesions, with multiple greyish and yellowish nodules. Microscopy revealed admixture of ganglion cells and Schwann cells, separated by myxoid stroma. Immunohistochemistry showed S-100 spindle cell component to be strongly positive; synaptophysin-ganglion cells positive, and neuron-specific enolase (NSE)-ganglion cells positive (Fig. 2b). All features led to the final diagnosis of a ganglioneuroma.

Chest X-ray showed resolution of the opacity in the left lower lung field (Fig. 2c). She was discharged from the hospital in a hemodynamically stable, afebrile, ambulatory condition on 6th POD. The patient had no particular complaints and was in good health with normal pulmonary function at 6 months’ follow-up visit.

Discussion

Ganglioneuroma is usually asymptomatic but can have non-specific symptoms related to mass effect and by compressing surrounding organs [5].

Wang et al. [6] have reported that there might be back pain due to spinal deformity. Scoliosis may be seen if tumor grows up to a significant size. Systemic complaints may include pain, dysphagia, dyspnea, shortness of breath, stridor, cough, changes in gait, weakness of muscles, or even Horner’s syndrome [7].

Ganglioneuroma has also been shown to have secretory function in up to 39% cases in some studies. [8] There might be elevated levels of metanephrine, catecholamine, vasoactive intestinal peptide, dopamine, cortisol, and vanillyl mandelic acid. Symptoms such as hypertensive crisis, diarrhea, virilization due to hormonal imbalance, and depression may be seen in such a case.

Malignant degeneration has been very rarely reported; thus, complete surgical removal is recommended. There is no need for neoadjuvant or adjuvant antineoplastic treatment, though [9].

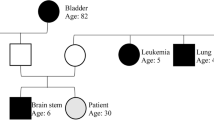

A systematic literature review by Kirchweger et al. [10] gave a cutoff for 10 cm for a ganglioneuroma to be labelled as large. It represented a subjective threshold, needed to give a complete overview of an understandable cohort in their study. A total of 64 such cases were reviewed, the time period ranging from June 1957 to January 2020. Thirteen such cases among them were thoracoabdominal in nature (Fig. 3).

Twelve out of 13 cases had no surgical complications or unexpected postoperative events. Only one had a hypertensive disorder. No relapse was seen, at a mean follow-up time period of 19.4 months.

In our case, the peculiarity was the unusual clinical nature of presentation, of a large-sized ganglioneuroma, as multi-loculated subpulmonic effusion. It was reaffirmed preoperatively by the radiological diagnosis as well. There were no constitutional symptoms or history, or possibility of any other infective etiology to suggest otherwise.

The subsequent challenges faced in operation due to abutment to the diaphragm and extensive adhesions caused a major hindrance and forced us to convert from our routine VATS approach to assisted VATS.

After histopathological diagnosis of the resected tissue was made, an unbiased, blinded review of the preoperative CT scan of the thorax was done again by two of our senior radiologists, and their findings were consistent with the original diagnosis. After checking that the Hounsfield unit values in various regions were consistent with fluid, there was no reason to suspect any solid mass too. Thus, this was a unique finding on its own. Hence, despite all clinical points and radiological investigations, ganglioneuroma should be considered in differential diagnosis of other intrathoracic tumors or, importantly, such subpulmonic loculated collection.

Routine follow-up, with imaging, is recommended as ganglioneuroma has slow progression potential and chances of late recurrence.

References

Decarolis B, Simon T, Krug B, Leuschner I, Vokuhl C, Kaatsch P, et al. Treatment and outcome of ganglioneuroma and ganglioneuroblastoma intermixed. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:542.

Linos D, Tsirlis T, Kapralou A, Kiriakopoulos A, Tsakayannis D, Papaioannou D. Adrenal ganglioneuromas: incidentalomas with misleading clinical and imaging features. Surgery. 2011;149:99–105.

Yang AI, Ozsvath J, Shukla P, Fatterpekar GM. Retropharyngeal ganglioneuroma: a case report. J Neuroimaging. 2013;23:537–9.

Yang Y, Ren M, Yuan Z, Li K, Zhang Z, Zhang J, et al. Thoracolumbar paravertebral giant ganglioneuroma and scoliosis: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:65.

Arab N, Alharbi A. Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma (GN): case report in 14 years old boy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;60:130–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.06.011.

Wang X, Yang L, Shi M, Liu X, Liu Y, Wang J. Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma combined with scoliosis: a case report and literature review. Medicine. 2018;97:e12328.

Gangadharan SP. Neurogenic tumors of the posterior mediastinum. In: Sugarbaker DJ, Bueno R, Colson YL, Jaklitsch MT, Krasna MJ, et al. Adult chest surgery. 2014 (2nd edn), McGraw-Hill, New York. (https://accesssurgery.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1317§ionid=72437522).

Geoerger B, Hero B, Harms D, Grebe J, Scheidhauer K, Berthold F. Metabolic activity and clinical features of primary ganglioneuromas. Cancer. 2001;91:1905–13.

Zheng X, Luo L, Han FG. Cause of postprandial vomiting - a giant retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma enclosing large blood vessels: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:2617–22.

Kirchweger P, Wundsam HV, Fischer I, Rösch CS, Böhm G, Tsybrovskyy O, et al. Total resection of a giant retroperitoneal and mediastinal ganglioneuroma—case report and systematic review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18:248. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-02016-1.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement

Not applicable as a solitary report with no patient identifiable information.

Statement of human and animal rights

It is confirmed that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Detailed informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chakraborty, U., Chakrabarti, A. & Bandyopadhyay, M. Ganglioneuroma presenting as subpulmonic effusion—a differential to consider?. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 39, 526–530 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12055-023-01522-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12055-023-01522-7