Abstract

Laparoscopic surgery is an acceptable alternative to open surgery in colorectal cancer treatment. However, in gastric cancer, there is not much scientific evidence. Here, we proposed a prospective randomized clinical trial to evaluate the radicalness and safety of laparoscopic D2 dissection for gastric cancer. From October 2010 to September 2012, 300 patients with gastric cancer were randomized to undergo either laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy (LAG) or conventional open gastrectomy (OG) with D2 dissection. Clinicopathological parameters, recovery and complications were compared between these two groups. Thirty cases were excluded because of refusing to be involved in the trial, having peritoneal seeding metastasis or LAG conversed to OG, and finally 270 cases were analyzed (128 in LAG and 142 in OG). No significant differences were observed in gender, age, body mass index, stages and types of radical resection [radical proximal gastrectomy (PG + D2), radical distal gastrectomy (DG + D2) and radical total gastrectomy (TG + D2)] (P > 0.05). The number of harvested lymph nodes (HLNs) was similar (29.3 ± 11.8 in LAG vs. 30.1 ± 11.4 in OG, P = 0.574). And in the same type of radical resection, no significant difference was found in the number of HLNs between the two groups (PG + D2, P = 0.770; DG + D2, P = 0.500; TG + D2, P = 0.993). The morbidity of the LAG group (21.8 %) was also comparable to the OG group (19.0 %, P = 0.560). However, the LAG group had significantly less blood loss and faster recovery, and a longer operation time (P < 0.05). Laparoscopic D2 dissection is feasible, safe and capable of fulfilling oncologic criteria for the treatment of gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors worldwide, and it is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Over 70 % of new cases and deaths occur in Eastern Asia, Eastern Europe and South America, including nearly 42 % in China [1, 2]. Gastric cancer represents a great challenge for healthcare providers and requires a multidisciplinary approach in which surgery remains the primary curative treatment for those without distant metastasis [3, 4]. Over the past two decades, minimally invasive surgery has been progressively developed. Since Kitano et al. [5] first performed laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy (LAG) for gastric cancer, LAG has gained acceptance widely.

Several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have shown that LAG can be performed in early gastric cancer (EGC) [6–13]. However, LAG for the treatment of advanced gastric cancer (AGC) remains controversial, mainly due to a lack of strong evidence demonstrating that laparoscopic D2 dissection is equivalent to open surgery. Some studies, including our retrospective study involving 209 patients with gastric cancer underwent laparoscopic or open surgery, have shown that laparoscopic D2 dissection is feasible, safe and capable of fulfilling oncologic criteria [14–20]. However, there are seldom large-scale RCTs comparing laparoscopic D2 dissection with open surgery. Therefore, we have designed a prospective randomized clinical trial to evaluate the feasibility, safety and short-term oncological outcome of the laparoscopic D2 dissection compared with open surgery for gastric cancer.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved and supervised by the Research Ethics Committee of Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute, Beijing, China (No. 2012071710). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Patients and preoperative management

From October 2010 to September 2012, 296 patients with gastric cancer at the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery I and Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery IV, Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute, were randomized to undergo either laparoscopic or conventional open gastrectomy with D2 dissection. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. Blood tests, double-contrast upper gastrointestinal X-ray studies, enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and gastric endoscopy were performed before operation. All tumors were diagnosed as adenocarcinomas by biopsy.

Randomization

Once eligibility was confirmed, the patients were then allocated to undergo either LAG with D2 dissection or conventional OG. Randomization was performed by closed envelopes and was balanced and stratified for proposed type of resection. Informed consent was signed prior to surgery from each case.

Surgical procedures

Anesthesia, trocar placement and surgical procedures were the same as our earlier report [16]. According to the guidelines of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA), the type of gastrectomy and extent of D2 dissection were determined by tumor location [21]. The aim of any oncological resection was to achieve en bloc resection of gastric segment and surrounding lymph nodes, in order to obtain adequate oncological clearance. All operations were performed by the same surgical team which had completed more than 150 cases of LAG before this study.

The standard D2 dissection in the radical total gastrectomy (TG) includes the removal of No. 1, 2, 3, 4sa, 4sb, 4d, 5, 6, 7, 8a, 9, 10, 11 and 12a lymph nodes. And after TG, the gastrointestinal continuity was restored in a Roux-en-Y fashion. The lymph nodes of No. 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8a, 9, 10 and 11 were dissected in the radical proximal gastrectomy (PG). Esophagogastric anastomosis was performed to rebuild gastrointestinal continuity following PG. The standard D2 dissection in the radical distal gastrectomy (DG), including No. 1, 3, 4sb, 4d, 5, 6, 7, 8a, 9, 11p and 12a, was conducted, and gastroduodenal anastomosis (Billroth I) or gastrojejunal anastomosis (Billroth II) was performed to rebuild gastrointestinal continuity afterward.

Nasogastric tube and nasojejunal tube were inserted routinely during operations. Enteral nutrition started through nasojejunal tube on the first postoperative day (POD). Gastroenterography, with the use of meglumine diatrizoate, was performed routinely to observe anastomosis on the seventh POD. If there was no evidence of anastomotic leakage by gastroenterography, the nasogastric tube could be removed and liquid diet was taken on the eighth POD.

Outcome measures

During surgery, operative time, blood loss (estimated by the volume of suction and the weight of gauze) and the amount of blood transfusion were recorded. Operative recovery, including first walking, first flatus and postoperative hospital stay, were also recorded. Postoperative complications were categorized as surgical and nonsurgical complications, which occurred during the hospital stay. Surgical complications included fluid needing drainage, infection, intra-abdominal or anastomotic bleeding needing transfusion or reoperation, ileus, delayed gastric emptying, lymphatic leakage and anastomotic leakage. Nonsurgical complications included cardiac, pulmonary, urinary, renal and hepatic complications. Mortality was defined as any death that occurred during hospital stay.

The depth of tumor invasion, tumor size, margins, the number of harvested lymph nodes (HLNs) and tumor cell-positive lymph nodes were determined by pathological analysis. Histological staging was classified according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging Manual.

The primary end point was operative mortality in 30 days after surgery. Secondary end point was operative recovery.

Statistical analysis

The data of patient’s age, body mass index (BMI), operation time, blood loss, HLNs, the time to first walking, the time to first flatus and the postoperative hospital stay were presented as \( \overline{\chi } \pm s \). Independent sample t test was used to estimate their differences. Differences were compared in gender, type of resection, stage and complications between the two groups using Chi-square test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 11.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA).

Results

Patient clinicopathologic characteristics

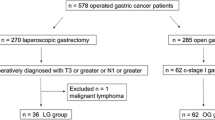

Four patients who refused involving in this trial were excluded. There were 296 patients randomized, 148 patients in the LAG group and 148 in the OG group. Among these patients, 20 cases were excluded in the LAG group including patients who declined any surgery, conversed to open surgery or had peritoneal seeding metastasis. Six patients with peritoneal seeding metastasis in the OG group were excluded (Fig. 1).

Demographic details of the two groups were shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences in gender, age and BMI between the two groups (P = 0.963, P = 0.078, and P = 0.131, respectively). There were 88 males and 40 females in the LAG group, and the mean age of patients was 60.1 years. The OG group included 98 males and 44 females, with a mean age of 57.5 years. The mean BMI in the LAG group was 23.03 and 23.66 in the OG group.

There were no significant differences in the type of radical resection between the LAG and OG groups (P = 0.195). Radical proximal gastrectomy with D2 dissection (PG + D2) was performed in 41 cases (23 in LAG and 18 in OG), radical distal gastrectomy with D2 dissection (DG + D2) in 148 cases (63 in LAG and 85 in OG) and radical total gastrectomy with D2 dissection (TG + D2) in 81 cases (42 in LAG and 39 in OG). Tumor-free margins were obtained in all the patients.

In addition, no significant differences were found in pathological stages between the two groups (P = 0.736). In the LAG group, there were 26 cases in stage I, 33 cases in stage II and 69 cases in stage III, while in the OG group, there were 33 cases in stage I, 39 cases in stage II and 70 cases in stage III.

However, the LAG group had a significantly less blood loss (99 ± 104 ml in LAG vs. 125 ± 62 ml in OG, P = 0.018), compared with the OG group. No blood transfusion was administered during surgery in both groups. And operating time was significantly longer in the LAG group than in the OG group (258 ± 80 min in LAG vs. 194 ± 49 min in OG, P < 0.0001, Table 2).

Number of harvested lymph nodes

The number of HLNs was regarded as an important factor to evaluate the quality of D2 dissection. Details of the number of HLNs are shown in Tables 3 and 4. All cases had 15 or more HLNs. The average number of HLNs was 29.3 ± 11.8 in the LAG group and 30.1 ± 11.4 in the OG group (P = 0.574). The number of HLNs in different types of resections was significantly different, which was 23.6 ± 7.3 in PG + D2, 29.2 ± 10.3 in DG + D2 and 33.7 ± 13.9 in TG + D2, respectively (P < 0.0001) (Table 3). However, in the same type of resection, there was no significant difference in the number of HLNs between the LAG and OG groups (PG + D2, 23.3 ± 7.0 in LAG vs. 23.9 ± 7.8 in OG, P = 0.770; DG + D2, 28.6 ± 10.0 in LAG vs. 29.7 ± 10.6 in OG, P = 0.500; TG + D2, 33.7 ± 14.7 in LAG vs. 33.7 ± 13.2 in OG, P = 0.993, respectively, Table 4).

Recovery and complications

Recovery and postoperative complications are listed in Table 5. Compared with the OG group, patients in the LAG group resumed walking and bowel function earlier (1.5 ± 1.1 in LAG vs. 1.9 ± 1.2 in OG, P = 0.004; 4.1 ± 1.5 in LAG vs. 4.7 ± 1.5 in OG, P = 0.002, respectively) and had shorter postoperative hospital stay (14.4 ± 10.0 in LAG vs. 18.2 ± 12.0 in OG, P = 0.005).

Postoperative complications in the LAG group and OG group included delayed gastric emptying (n = 12 in LAG vs. n = 4 in OG), anastomotic leakage (n = 3 in LAG vs. n = 4 in OG), abdominal infection (n = 3 in LAG vs. n = 7 in OG), anastomotic bleeding needed transfusion (n = 3 in LAG vs. n = 4 in OG), lymphatic leakage (n = 2 in LAG vs. n = 1 in OG), large pleural effusion needed drainage (n = 2 in LAG vs. n = 5 in OG) and pneumonia (n = 1 in LAG vs. n = 1 in OG). Wound infection only occurred in one case in the OG group. There were no significant differences in the morbidity between the two groups (21.8 % in LAG vs. 19.0 % in OG, P = 0.560). However, delayed gastric emptying seemed to occur more often in the LAG group (P = 0.022). Mortality did not happen in both groups.

Discussion

In this study, we proposed a prospective RCT to evaluate the radicalness and safety of LAG with D2 dissection for gastric cancer resection. The results showed that compared with the OG group, patients in the LAG group had less blood loss, earlier recovery, shorter postoperative hospital stay and comparable morbidity. In short, laparoscopic D2 dissection is feasible, safe and capable of fulfilling oncologic criteria for gastric cancer treatment.

For the treatment of gastric cancer, operation is considered as the only radical treatment. Surgical procedures include gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy. D2 dissection has been the standard operation for advanced gastric cancer (AGC) accepted by Eastern and Western investigators gradually [22, 23]. The 2014 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline recommended that gastric cancer surgery should remove D2 lymph nodes with the goal of examining fifteen or more lymph nodes.

Although D2 dissection is performed in AGC as a standard procedure, more and more investigators have emphasized the need for D2 dissection in early gastric cancer (EGC) because of underestimation of preoperative stage [24–26]. In our center, about 90 % of gastric cancers were initially diagnosed as AGC, and it was very difficult to diagnose EGC accurately before operation. Therefore, standard D2 dissection is routinely performed in all patients with gastric cancer in this trial.

The number of HLNs is regarded as an important factor, not only indicating short-term oncological outcome, but also influencing long-term survival. There is still debate about whether the number of HLNs in LAG is similar to OG with D2 lymph node dissection. Some studies demonstrated that the number of HLNs in laparoscopic D2 dissection was less than that in the open D2 dissection [20, 27, 28]. For instance, a large-scale Korean multicenter study comprised 2976 gastric cancer patients treated with curative intent either by LAG (1477 patients) or by OG (1499 patients) [20]. And they showed that the number of HLNs was significantly less in the LAG than in the OG group (31.76 ± 13.50 in LAG vs. 39.92 ± 16.90 in OG, P < 0.001) [20]. Jeong et al. [28] reported similar results in the number of HLNs (25 ± 13 in LAG vs. 30 ± 14 in OG, P < 0.01). Unfortunately, in these studies, the distribution of stages and the extent of lymph node dissection were not balanced between the two groups. The percentages of AGC and D2 dissection in the OG group were higher than in the LAG group (P < 0.05). This variability might explain the different number of HLNs between the two groups. On the contrary, several studies have shown that the number of HLNs of laparoscopic D2 dissection was the same as open dissection [16–19, 24, 29–31]. Lee et al. [19] retrospectively analyzed 1874 patients with gastric cancer: 1058 patients underwent LAG and 816 patients underwent OG. No significant differences were found in the number of HLNs between the two groups regardless of tumor progression (AGC or EGC) or extent of lymphadenectomy (D1 + or D2). Cai et al. [30] evaluated 96 AGC patients who underwent D2 gastrectomy: 49 cases were randomized in the LAG group and 47 cases in the OG group. A similar number of HLNs was obtained in both groups (22.98 ± 2.704 vs. 22.87 ± 2.428, P = 0.839). However, there were only a few prospective studies comparing the number of HLNs between LAG and OG. In our prospective RCT study, all patients had fifteen or more HLNs. The mean number of HLNs was comparable between the LAG and OG groups (29.3 ± 11.8 vs. 30.1 ± 11.4, P = 0.574). In addition, we also analyzed the number of HLNs in different subgroups (PG + D2, DG + D2 and TG + D2) in the LAG and the OG groups. The results showed the same trend that there were no significant differences in the number of HLNs between the LAG group and the OG group (P = 0.770 in PG + D2, P = 0.500 in DG + D2, and P = 0.993 in TG + D2, respectively). To our knowledge, this is the first published prospective RCT that systematically compares the number of HLNs in different types of radical gastrectomies between LAG group and OG group.

Some retrospective studies have shown that LAG appears to offer many advantages including less blood loss, faster recovery, shorter postoperative hospital stay and comparable morbidity compared with OG [6, 9, 10, 31, 32]. Consistent with previous studies, this prospective RCT also showed the similar results of LAG with these advantages, compared with OG.

In our study, all patients were accepted at one center, and all operations, including LAG and OG, were performed by the same surgical team which had completed more than 150 cases of LAG before this trial. Moreover, this study was a prospective RCT without significant difference in gender, age, BMI and the types of resection between the LAG group and the OG group, and all cases had fifteen or more HLNs, according to the recommendation in the NCCN guidelines. All of these favor the performance of the study.

However, there are still some limitations. The clinical trial was performed only in a single Chinese hospital. Recently, a prospective multicenter RCT designed by our center is ongoing. Moreover, long-term survival needs to be evaluated and compared between the LAG and the OG groups in future studies.

In conclusion, LAG with D2 dissection can be considered as a safe and feasible procedure for the radical cure of patients with gastric cancer. And it provides similar short-term oncological outcomes compared to OG-treated patients. In order to determine the long-term clinical outcomes of LAG with D2 dissection, longer follow-up of this prospective RCT is ongoing.

References

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90.

Lin Y, Ueda J, Kikuchi S, Totsuka Y, Wei WQ, Qiao YL, Inoue M. Comparative epidemiology of gastric cancer between Japan and China. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4421–8.

Dikken JL, van de Velde CJ, Coit DG, Shah MA, Verheij M, Cats A. Treatment of resectable gastric cancer. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5:49–69.

Takahashi T, Saikawa Y, Kitagawa Y. Gastric cancer: current status of diagnosis and treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2013;5:48–63.

Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146–8.

Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Fujii K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Adachi Y. A randomized controlled trial comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for the treatment of early gastric cancer: an interim report. Surgery. 2002;131:S306–11.

Fujii K, Sonoda K, Izumi K, Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Kitano S. T lymphocyte subsets and Th1/Th2 balance after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1440–4.

Lee JH, Han HS, Lee JH. A prospective randomized study comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer: early results. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:168–73.

Hayashi H, Ochiai T, Shimada H, Gunji Y. Prospective randomized study of open versus laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with extraperigastric lymph node dissection for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1172–6.

Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, Bae JM. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248:721–7.

Kim YW, Yoon HM, Yun YH, Nam BH, Eom BW, Baik YH, Lee SE, Lee Y, Kim YA, Park JY, Ryu KW. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: result of a randomized controlled trial (COACT 0301). Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4267–76.

Sakuramoto S, Yamashita K, Kikuchi S, Futawatari N, Katada N, Watanabe M, Okutomi T, Wang G, Bax L. Laparoscopy versus open distal gastrectomy by expert surgeons for early gastric cancer in Japanese patients: short-term clinical outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1695–705.

Takiguchi S, Fujiwara Y, Yamasaki M, Miyata H, Nakajima K, Sekimoto M, Mori M, Doki Y. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy versus open distal gastrectomy. A prospective randomized single-blind study. World J Surg. 2013;37:2379–86.

Du J, Zheng J, Li Y, Li J, Ji G, Dong G, Yang Z, Wang W, Gao Z. Laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy with extended lymph node resection for advanced gastric cancer—reports of 82 cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:1589–94.

Huang JL, Wei HB, Zheng ZH, Wei B, Chen TF, Huang Y, Guo WP, Hu B. Laparoscopy-assisted D2 radical distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Dig Surg. 2010;27:291–6.

Cui M, Xing JD, Yang W, Ma YY, Yao ZD, Zhang N, Su XQ. D2 dissection in laparoscopic and open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:833–9.

Qiu JF, Yang B, Fang L, Li YP, Shi YJ, Yu XC, Zhang MC. Safety and efficacy of laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer in the elderly. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:3562–7.

Fang C, Hua J, Li J, Zhen J, Wang F, Zhao Q, Shuang J, Du J. Comparison of long-term results between laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy and open gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2014;208:391–6.

Lee JH, Lee CM, Son SY, Ahn SH, Park DJ, Kim HH. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: long-term oncologic results. Surgery. 2014;155:154–64.

Kim HH, Han SU, Kim MC, Hyung WJ, Kim W, Lee HJ, Ryu SW, Cho GS, Song KY, Ryu SY. Long-term results of laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: large-scale case-control and case-matched Korean multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:627–33.

Association Japanese Gastric Cancer. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma—2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1(10–24):20.

Degiuli M, Sasako M, Ponti A, Calvo F. Survival results of a multicentre phase II study to evaluate D2 gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1727–32.

Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomized nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:439–49.

Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Brachini G, Binda B, Di Paola M, Ponzano C. Totally laparoscopic total and subtotal gastrectomy with extended lymph node dissection for early and advanced gastric cancer: early and long-term results of a 100-patient series. Am J Surg. 2007;194:839–44.

Pugliese R, Maggioni D, Sansonna F, Ferrari GC, Forgione A, Costanzi A, Magistro C, Pauna J, Di Lernia S, Citterio D, Brambilla C. Outcomes and survival after laparoscopic gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma. Analysis on 65 patients operated on by conventional or robot-assisted minimal access procedures. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:281–8.

Lee SR, Kim HO, Son BH, Shin JH, Yoo CH. Laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy versus open total gastrectomy for upper and middle gastric cancer in short-term and long-term outcomes. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24:277–82.

Lee SI, Choi YS, Park DJ, Kim HH, Yang HK, Kim MC. Comparative study of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy and open distal gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:874–80.

Jeong SH, Lee YJ, Park ST, Choi SK, Hong SC, Jung EJ, Joo YT, Jeong CY, Ha WS. Risk of recurrence after laparoscopy-assisted radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer performed by a single surgeon. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:872–8.

Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, Ponzano C. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232–7.

Cai J, Wei D, Gao CF, Zhang CS, Zhang H, Zhao T. A prospective randomized study comparing open versus laparoscopy-assisted D2 radical gastrectomy in advanced gastric cancer. Dig Surg. 2011;28:331–7.

Li HT, Han XP, Su L, Zhu WK, Xu W, Li K, Zhao QC, Yang H, Liu HB. Short-term efficacy of laparoscopy-assisted vs open radical gastrectomy in gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;6:59–64.

Kim HH, Hyung WJ, Cho GS, Kim MC, Han SU, Kim W, Ryu SW, Lee HJ, Song KY. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an interim report—a phase III multicenter, prospective, randomized trial (KLASS Trial). Ann Surg. 2010;251:417–20.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81272766, 81450028), the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program, No. 2014AA020603), Clinical Characteristics and Application Research of Capital (Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission, No. Z121107001012130), Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (No. XM201309), Peking University (PKU) 985 Special Funding for Collaborative Research with PKU Hospitals (To Xiangqian Su and Fan Bai), Seeding Grant for Medicine and Life Sciences of Peking University (2014-MB-04), Science Foundation of Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute (No. 2014-14).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

The studies have been approved by the research ethics committee of Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute, Beijing, China (Approved No. 2012071710) and have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Ming Cui and Ziyu Li have contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, M., Li, Z., Xing, J. et al. A prospective randomized clinical trial comparing D2 dissection in laparoscopic and open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Med Oncol 32, 241 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-015-0680-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-015-0680-1