Abstract

Purpose

Gastric cancer is endemic in the so-called stomach cancer region comprising Rwanda, Burundi, South Western Uganda, and eastern Kivu province of Democratic Republic of Congo, but its outcomes in that region are under investigated. The purpose of this study was to describe the short-term outcomes (in-hospital mortality rate, length of hospital stay, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month survival rates) in patients treated for gastric cancer in Rwanda.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the data collected from records of patients who consulted Kigali University Teaching Hospital (CHUK) over a period of 10 years from September 2007 to August 2016. We followed patients before and after discharge for survival data. Baseline demographic data studied using descriptive statistics, whereas Kaplan-Meier model and univariate Cox regression were used for survival analysis.

Results

Among 199 patients enrolled in this study, 92 (46%) were males and 107 (54%) females. The age was ranging between 24 and 93 years with a mean age of 55.4. The mean symptom duration was 15 months. Many patients had advanced disease, 62.3% with distant metastases on presentation. Treatment with curative intent was offered for only 19.9% of patients. The in-hospital mortality rate was 13.3%. The 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month survival rate was 52%, 40.5%, 28%, and 23.4%, respectively. The overall survival rate was 7 months.

Conclusion

Rwanda records a high number of delayed consultations and advanced disease at the time of presentation in patients with gastric cancer. This cancer is associated with poor outcomes as evidenced by high hospital mortality rates and short post discharge survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignant diseases with significant geographical, ethnic, and socioeconomic differences in distribution. It was the leading cause of cancer deaths in the world until the lung cancer took the lead in 1980s [1], but it has remained a major public health concern.

The three most common primary malignant gastric neoplasms are adenocarcinoma (95%), lymphoma (4%), and malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) (1%) [2].

The incidence of gastric cancer is approximately 985,600 globally, and about two thirds of them are from developing countries with 738,000 minimum expected deaths [3]. Approximately 22,220 patients are diagnosed each year in the USA, and, of whom, 10,990 deaths are expected [1].

There is a high incidence of gastric cancer in China, Japan, Korea, South America, and Eastern Europe, but the incidence is comparatively low in most of Europe, North America, and Africa. There is a low prevalence of gastric cancer in sub-Saharan Africa with western Africa having the lowest incidence rates [3].

Gastric cancer is endemic in the so-called stomach cancer region comprising Rwanda, Burundi, South Western Uganda, and eastern Kivu province of Democratic Republic of Congo [4]. Its incidence in the great lakes region is estimated at 3.2/100,000 population. I is not clear why gastric cancer is common in this region, but one of the suspected causes is the lack of trace minerals in the volcanic soil thereof.

In Rwanda, the incidence of gastric cancer is 13 to 15 per 100,000 population which is high compared to the regional incidence (3.2 per 100,000 in Great Lakes region) [5]. Available studies on gastric cancer in Rwanda suggest that the mean age on presentation falls in the 6th decade of life [6,7,8], with a mean symptoms duration of 12 months [b]. Common clinical features include epigastric pain, vomiting, and muscle wasting [a]. Gastric outlet obstruction and a palpable abdominal mass are present in 18.8% and 13.5%, respectively [7].

Gastric cancer has been showing improved outcomes over the last decades as evidenced by low postoperative mortality rates, shorter hospital stays, and improved overall survival but the results of treatment remain poor with the prognosis depending mainly on the stage of the disease [9].

Most of gastric cancer patients in developing countries undergo palliative surgery because of the very low possibility of cancer resection as a result of delayed consultation and diagnosis [10,11,12]. The results are subsequently poor with high complication rate post-operatively (up to 37.1%), high post-operative mortality rates (13.8% to 18.1%), and shorter survival rates compared to developed countries [11, 13,14,15]. In Rwanda, the curative resection was possible in 29% of patients with gastric cancer in one study report [b] and there are no survival data currently available in the country.

Late patient presentation, scarcity of diagnostic tools and workforce, limited treatment modalities, and many other factors compromise the outcome of patient with gastric cancer in countries with limited resources. There are scarce of studies that explored the outcomes of gastric cancer in terms of survival rates in Rwanda. The aim of this study was to describe the short-term outcomes (in-hospital mortality rate, length of hospital stay, 3 months, 6 months, 1- and 2-year survival rates) in patients with gastric cancer at CHUK.

Methods

This was a retrospective study on the short-term outcome of patients with gastric cancer who were treated at CHUK over a period of 10 years from September 2007 to August 2016. CHUK is a 560-bed tertiary level hospital, the largest public hospital in the country located in Nyarugenge District, Kigali, Rwanda.

The study included patients who consulted CHUK in the study period with a diagnosis of gastric cancer confirmed by histopathology. Patients with missing or incomplete record files and those with missing contact details were excluded from the study.

Patients were identified through the department of pathology records. Patient files, endoscopy logs, and electronic medical records were reviewed to select patients qualifying for enrollment.

Only patients with gastric cancer confirmed by histopathology were considered in this study, and they were further classified using both the World Health Organization classification (tubular, mucinous, papillary, signet ring cell carcinoma, and other poorly cohesive carcinoma) and the Lauren classification (intestinal, diffuse, and mixed or indeterminate types) [16]. The tumors were also graded with regard to their degree of differentiation into poorly differentiated or undifferentiated tumors (also referred to as high grade tumors, these are tumors whose cancer cells look and act less normal or more abnormal; they tend to grow more quickly and are likely to spread) and well-differentiated tumors (also referred to as low grade tumors, their cells look and act much like normal cells; these ones tend to grow slowly and are less likely to spread [17].

Demographic data, clinical data, operative details, and post-operative follow-up data were recorded from patients’ record files. Post discharge data were obtained from data from Outpatient Department for those who came back for follow-up, or via phone calls for those who did not. For patients who did not answer phone calls (115), information was obtained via community health workers of their village (112) or by physically going to the address they provided at the time of their hospital registration(3). Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 was used for data analysis. The primary outcomes were 3-month, 6-month, 12-month, and 24-month survival rates. The secondary outcome was length of hospital stay. Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic and other baseline characteristics of patients. Kaplan-Meier model and univariate Cox regression were used to describe survival rate and find related prognostic factors, respectively.

Results

A total of 158 patients were enrolled in the study, 73 (46%) were males and 85 (54%) were females. The mean age was 55.4 (24–93) years, and the mean duration of symptoms was 15 months. Patients consulted from all 5 provinces of Rwanda; the Northern Province had the highest number of patients with gastric cancer (Table 1).

The table above shows demographic data of patients with gastric cancer at CHUK in the period from September 2007 to August 2016. A big number of patients 68 (43.03) were 60 years old or older or above whereas only 8 (5.06%) were 30 years old or younger. The Northern Province was the most represented with 52 (32.91%) patients and 41 (25.94%) patients consulted after 7 to 12 months of onset of symptoms.

According the Lauren classification, the most common histology type was adenocarcinoma, intestinal type 77 (48.7%), followed by diffuse type 69 (43.7%). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, the signet ring cell carcinoma was the most common histologic type with 79 (50%) patients. Most of the patients presented with advanced disease (stage III and IV) representing 74% of enrolled patients including 62.3% with metastatic disease (Table 2).

Among 71 (45%) patients who underwent surgical management, 31 (19.8%) were operated with curative intent whereas 40 (25.2%) were operated for palliation. The curative surgical procedures included total gastrectomy in 2 (1.3%) patients and partial gastrectomy in 29 (18.5%) patients, whereas palliative surgical procedures included 32 (20.2%) gastric bypass procedures and 8 (5%) exploratory laparotomies without further action. The remaining 87 (55%) patients who did not undergo surgery were treated with non-operative palliative treatment including intravenous fluids, oxygen support, nutrition support, analgesics, and palliative chemotherapy (Table 3).

Our patients had a mean length of hospital stay (LoHS) of 13.2 days, 69 (43.7%) patients spending a week or less in the hospital and 23 (14.5%) patients spending 3 or more weeks (Table 4).

The overall in-hospital mortality rate for patients diagnosed with gastric cancer was 13.3%.

After hospital discharge, 82 (52%) and 64 (40.5%) patients were still alive after 3 and 6 months, respectively.

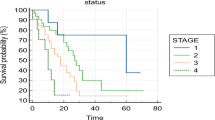

The 1-year survival rate was 27.8% whereas the 2-year survival rate was 23.4% (Fig. 1).

The overall median survival in gastric cancer patients was 7 months. The median survival rate for patients operated for gastric cancer was 10.4 months while it was only 1.6 months for patients who did not undergo surgery.

With regard to the intent of treatment, for patients operated with curative intent, 75% were still alive after 2 years whereas among those who underwent palliative procedures, only 11.1% survived beyond the same period. None of the patients who were not operated on survived beyond 2 years (Fig. 2).

The prognostic factors were age of the patient, the degree of differentiation of the tumor, and the intent of surgery.

Patients aged from 30 to 40 years were 2 times more likely to die of gastric cancer compared to patients aged 60 years and above (hazard ratio (HR): 2.082, 95% CI: 1.217–3.562, p value: 0.007). Patients younger than 30 years and those aged from 40 to 59 years did not show any survival benefit compared to those aged 60 years and above (Table 5).

Patients with poorly differentiated gastric cancer were 2.6 times more likely to die of gastric cancer compared to those with well-differentiated tumors (HR: 2.594, 95% CI: 1.235–5.444, p value: 0.012).

Patients operated with palliative intent were 3 times likely to die compared to those operated with curative intent (HR: 3.101, 95% CI: 1.766–5.445, p value: 0.001).

Discussion

This study aimed at evaluating the short-term outcomes of patients diagnosed with gastric cancer in terms of hospital mortality and survival rates. It represents one of the few, if not the first study done in Rwandan that assessed the outcome of gastric cancer treatment beyond discharge from the hospital. In addition to outcomes, the present study established baseline demographic data of patients diagnosed with gastric cancer and identified some of the factors associated with mortality.

The mean age of patients with gastric cancer in this study was 55.4 years and this corroborates the findings from other sub-Saharan countries where the mean age is usually between 50 and 55 years [10, 11, 15]. Our patients developed gastric cancer at a younger age compared to patients from developed countries where a mean age above 60 years is usually reported [19,20,21].

The patients in this study had a delayed presentation with a mean duration of symptoms of 15 months from the onset of the first symptom to the time of the diagnosis. A delay in presentation was previously reported in Rwanda in 2018 with a median symptomatic period of 12 months [7]. A delay in consultation and diagnosis is mainly a consequence of insufficient providers and equipment, with only 4 public hospitals in Rwanda having endoscopic facilities for a population of 12.63 million in 2019. Several patients (74%) presented with advanced gastric cancer (stage III and IV) at the time of the diagnosis. A delay in presentation is common in sub-Saharan countries with 92.1% patients presenting with advanced gastric cancer in one report [8]. The fact that patients presented with advanced disease has negatively affected their management, limiting the treatment options to palliative surgery in 25.3% or to non-surgical palliative treatment, like intravenous fluid therapy, analgesics, nutrition and oxygen supplementation for 55% of patients. In this study, only 45% of patients underwent surgery, and only 19.8% of them were operated with curative intent while the remaining 25.2% had palliative surgery. Palliative surgical procedures mainly consisted of gastrojejunostomy (with or without jejunojejunostomy) and feeding jejunostomy. Similar findings were reported in Togo where the surgical management was possible in 46% of patients with gastric cancer including 15% palliative surgeries [10]. Though the proportion of patients who undergo palliative surgeries is still high in Rwanda, it has markedly decreased compared to the findings of previous study done in 2007 where 97.1% of operated patients underwent palliative procedures [12].

The in-hospital mortality rate in our study was 13.3% which is consistent with the mortality rate reported in other sub-Saharan countries varying between 13.8 and 18.1% [10, 11, 15].

Gastric cancer was associated with poor outcomes, with an overall median survival of 7 months which is almost half of the median survival of 13.6 months found in Nigeria [15] and 1.09 years found in China [18]. The 1-year survival rate of 28% found in this study was low compared to 51% and 52% reported in China for males and females, respectively [18]. The median survival rate was 10.4 months in patients who underwent surgery and 1.6 months for those who did not undergo surgery. This was expected because patients who were not operated on were judged to be in poor clinical status either due to the disease itself or due to the presence of other poor prognostic factors like severe malnutrition, comorbidities, or advanced malignancy. Those patients were managed with non-operative palliative measures such as intravenous fluids, pain killers, oxygen therapy, and nutrition support where applicable.

The present study identified that age group in the thirties, presence of a poorly differentiated tumor, and the surgical procedure with palliative intent were associated with poor prognosis.

With regard to the age, most of the existing literature agrees that it does not affect the outcomes [22,23,24,25] or that advanced age negatively impacts outcomes in patients with gastric cancer [20, 21, 26, 27]. Some studies, however, reported high prevalence of aggressive forms of cancer (poorly differentiated tumors, diffuse type, and signet ring cell carcinoma) and other poor prognostic factors such as upper location of the tumor and advanced stage at presentation in the young population [19, 28, 29]. The fact that the younger patients usually have better survival rates compared to old ones despite the presence of these poor prognostic factors suggests that age is not an independent predictor of mortality in patients with gastric cancer.

A poor prognosis in patients younger than 35 years was reported in some countries [30, 31] and there is some evidence that gastric cancer could be associated with poor outcomes in extremes of age (in younger population and in elderly) because of high prevalence of poor prognostic factors in the former group and the presence of comorbidities and cellular senescence in the latter, suggesting that, as far as age is concerned, a better prognosis is expected in the middle aged population [19]. There is no conventional age cutoff to define elderly patients but the age of 65, 70, or 75 are commonly considered in the literature [32,33,34,35,36].

We did not find any factor that could explain high mortality in patients aged between 30 and 39 since none of poor prognostic factors reported in the literature was most prevalent in this specific age group and a large study with multivariate analysis is required to establish the role of the age on the survival of patients with gastric cancer in Rwanda.

Regarding the grade of the tumor, this study found that poorly differentiated tumors were negative predictors of survival (p: 0.012) and this corroborates the existing evidence of gradual decrease of survival with respect to the differentiation status [37].

The association between palliative surgery and mortality was expected since palliative procedures were performed on patients with advanced stage of the disease and poor functional status.

The effect of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies on patients’ outcomes was not assessed in this study because of insufficient data. Chemotherapy was not available in the country in the first 4 years of the study period and there was no radiation therapy available in the country over the entire study period.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study assessing the outcome of patients with gastric cancer beyond discharge from the hospital in Rwanda, and it was conducted in the largest public hospital of the country. It covered an extended period of time (10 years) and included patients from all the provinces of the country.

The limitations of this study are that it is a single center study based on retrospectively collected data. There were missing data especially about classification and follow-up, which decreased considerably the number of study participants from 241 to 158. Moreover, most of the study participants (115) could not be reached directly via phone calls and we had to contact Community Health Workers located at their villages or to go physically to the address they had provided during the hospital registration at the time of their first visit to CHUK. The future studies should focus on a long-term follow-up project conducted on a larger population in order to provide much more information on outcomes of patients with gastric cancer and to help to evaluate the impact of treatment modalities other than surgery alone on the outcomes.

Conclusion

Gastric cancer was associated with delayed presentation and advanced disease at the time of the diagnosis, with the treatment options limited to palliative care in many patients. Gastric cancer had poor outcomes as evidenced by high mortality and short survival. This knowledge will improve gastric cancer awareness among the general population and will help clinicians to communicate with patients diagnosed with gastric cancer about the expected treatment options and their outcomes.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CHUK:

-

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Kigali (University Teaching Hospital of Kigali)

- GIST:

-

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- LOHS:

-

Length of hospital stay

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

References

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics (2014). CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64(1):9–29.

Brunicardi FC. Schwartz principles of surgery, 10th edition. 2015.

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;55:74–108.

Wabinga H. Helicobacter pylori and histopathological changes of gastric mucosa in Uganda population with varying prevalence of stomach cancer. Afr Health Sci. 2005;5(3):234–7.

Newton R, Ngilimana PG, Grulich A, Beral V, Sindikubwabo B, Nganyira A, et al. Cancer in Rwanda. Int J Cancer. 1996;66(1):75–81.

Habyarimana O, et al. The potential for targeted therapies among gastric tumor patients at Kigali University Teaching Hospital, Rwanda. Dissertation, UR. 2017.

Martin AN, Silverstein A, et al. Impact of delayed care on surgical management of patients with gastric cancer in a low-resource setting. J Surg Oncol. 2018;118(8):1237–42.

Kabuyaya M, SSebuufu R, et al. The frequency of gastric cancer among patients presenting with GOO in Rwanda. RMJ. 2013;70(4):35.

Antanas M, Povilas I, Rytis M, Audrius P, Dainora B, Mindaugas K, Zilvinas E, Almantas M, Zilvinas D. Trends and results in treatment of gastric cancer over last two decades at single East European centre: a cohort study. BMC Surg. 2014;14:98. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2482/14/98.

Ayite AE, Adodo K, et al. Management of primary gastric cancer at university hospitals in Lome. Report of 63 cases. Tunis Med. 2004;82(8):747–52.

Mabula JB, Mchembe MD, Koy M, Chalya PL, Massaga F, Rambau PF, Masalu N, Jaka H. Gastric cancer at a university teaching hospital in Northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 232 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:257. http://www.wjso.com/content/10/1/257.

Ntakiyiruta G. Gastric cancers at Kibogora hospital. East and Central African Journal of Surgery. 2009;14(1);130–34.

Howlader NA, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2014. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/, based on November 2016 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. 2017.

Cancer Research UK. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/stomach-cancer/survival#heading-Two. Accessed 13 Nov 2018.

Ahmed A, Ukwenya AY, et al. Management and outcome of gastric carcinoma in Zaria. Nigeria African Health Sciences. 2011;11(3):353–61.

Bing H, Nassim EH, Sittler S, Lammert N, Barnes R, Meloni-Ehrig A. Gastric cancer: classification, histology and application of molecular pathology. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3(3):251–61. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.021.

Canadian Cancer Society. Grading and classifying stomach cancer. https://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/stomach/grading/?region=on. Accessed 20 Apr 2021.

Zheng L, Wu C, Xi P, et al. The survival and the long-term trends of patients with gastric cancer in Shanghai, China. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:300. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-300.

Schlesinger-Raab A, Mihaljevic AL, et al. Outcome of gastric cancer in the elderly: a population-based evaluation of the Munich Cancer Registry. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:713–22.

Fujiwara Y, Fukuda S, Tsujie M, Ishikawa H, Kitani K, Inoue K, Yukawa M, Inoue M. Effects of age on survival and morbidity in gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;9(6):257–62.

Saito H, Osaki T, Murakami D, Sakamoto T, Kanaji S, Tatebe S, Tsujitani S, Ikeguchi M. Effect of age on prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:458–61.

Bausys R, Bausys A, et al. Surgical treatment outcomes of patients with T1–T2 gastric cancer: does the age matter when excellent treatment results are expected? World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:79.

Bautista M, Jiang SF, Armstrong M. Impact of age on clinicopathological features and survival of patients with non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma. J Gastric Cancer. 2014;4:238–46.

Ramos MFKP, Pereira MA, et al. Gastric cancer in young adults: a worse prognosis group? Rev Col Bras Cir. 2019;46(4):e20192256.

Qiu M, Wang Z, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic analysis of gastric cancer in the young adult in China. J Transl Med. 2011;32:509–14.

Medrano-Guzman R, Valencia-Mercado D, Luna-Castillo M, Garcia-Rios LE, Rodriguez DG. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with resectable advanced gastric adenocarcinoma. Cir Cir. 2016;84(6):469–76.

Qiu MZ, Wang ZQ, Zhang DS, Luo HY, Zhou ZW, Wang FH, Li YH, Jiang WK, Xu RH. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic analysis of gastric cancer in the young adult in China. Tumor Biol. 2011;32:509–14.

Koea JB, Karpeh MS, Brennan MF. Gastric cancer in young patients: demographic, clinicopathological, and prognostic factors in 92 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:346–51.

Park JC, Lee YC, et al. Clinicopathological aspects and prognostic value with respect to age: an analysis of 3,362 consecutive gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:395–401.

Nakamura R, Saikawa Y, et al. Retrospective analysis of prognostic outcome of gastric cancer in young patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16:328–34.

Guan WL, Yuan LP, Yan XL, Yang DJ, Qiu MZ. More attention should be paid to adult gastric cancer patients younger than 35 years old: extremely poor prognosis was found. J Cancer. 2019;10(2):472.

Dudeja V, Habermann EB, Zhong W, Tuttle TM, Vickers SM, Jensen EH, et al. Guideline recommended gastric cancer care in the elderly: insights into the applicability of cancer trials to real world. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:26–33.

Gretschel S, Estevez-Schwarz L, Hünerbein M, Schneider U, Schlag PM. Gastric cancer surgery in elderly patients. World J Surg. 2006;30:1468–74.

Biondi A, Cananzi FC, et al. The road to curative surgery in gastric cancer treatment: a different path in the elderly? J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:858–67.

Gillison TL, Chatta GS. Cancer chemotherapy in the elderly patient. Oncology (Williston Park). 2010;24:76–85.

Destri GL, Cavallaro M, et al. Colorectal cancer treatment and follow-up in the elderly: an inexplicably different approach. Int Surg. 2012;97:219–23.

Feng F, Liu J, et al. Prognostic value of differentiation status in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4780-0.

Funding

This study did not receive any funds, grants, or other support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IN and EA: protocol conception; IN, JCU, and AN: design of the work; VM, JMVK, and KID: acquisition and analysis of the data; IN, IS, and EA: interpretation of the data, drafting of the work, and its revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Rwanda (IRB/CMHS/UR) and the Research and Ethical Committee of University Teaching Hospital of Kigali (CHUK). Participants were enrolled after an informed consent.

Consent for Publication

All the study participants or their legal representatives where applicable have consented for publication of the results of this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Niyongombwa, I., Karenzi, I.D., Sibomana, I. et al. Short-term Outcomes of Gastric Cancer at University Teaching Hospital of Kigali (CHUK), Rwanda. J Gastrointest Canc 53, 520–527 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-021-00645-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-021-00645-7