Abstract

Background

Intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and spinal subdural hematoma (SDH) are rare complications of spine surgery, thought to be precipitated by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hypotension in the setting of an intraoperative durotomy or postoperative CSF leak. Considerable clinical variability has been reported, requiring a high level of clinical suspicion in patients with a new, unexplained neurologic deficit after spine surgery.

Methods

Case report.

Results

An 84-year-old man developed symptomatic spinal stenosis with bilateral lower extremity pseudoclaudication. He underwent L3-5 laminectomy at an outside institution, complicated by a small, incidental, unrepairable intraoperative durotomy. On postoperative day 2, he became confused; and head CT demonstrated intracranial SAH with blood products along the superior cerebellum and bilateral posterior Sylvian fissures. He was transferred to our neurosciences ICU for routine SAH care, with improvement in encephalopathy over several days of supportive care. On postoperative day 10, the patient developed new bilateral lower extremity weakness; MRI of the lumbar spine demonstrated worsening acute spinal SDH above the laminectomy defect, from L4-T12. He was taken to the OR for decompression, at which time a complex 1.5-cm lumbar durotomy was identified and repaired primarily.

Conclusions

We report the first case of simultaneous intracranial SAH and spinal SDH attributable to postoperative CSF hypotension in the setting of a known intraoperative durotomy. Although rare, each of these entities has the potential to precipitate a poor neurologic outcome, which may be mitigated by early recognition and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is an exceedingly rare complication of spine surgery, with approximately 40 cases reported in the literature [7, 12, 18]. By contrast, incidental durotomy is among the most frequent intraoperative complications of spine surgery, with large prospective series documenting an incidence ranging from 3.1 % in routine discectomy to 17.4 % in revision fusion [6, 44]. Rates of recurrent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak range from 1 to 5 %; secondary complications of recurrent CSF leak are rare but have been reported to include headache, nausea, vomiting, meningismus, cognitive changes, seizures, and both subdural hematoma (SDH) and SAH [3, 5, 11, 18, 19, 32, 42, 47]. As compared to intracranial SDH—a frequent and dangerous consequence of CSF hypotension from any source—spinal SDH caused by CSF hypotension is exceedingly rare, though single cases have been described after both cranial and spinal surgery [10, 21, 42]. We present a case of combined SAH and SDH attributable to a recurrent CSF leak after incidental durotomy during routine lumbar laminectomy.

Case History

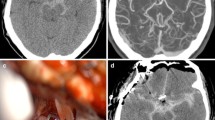

An 84-year-old man presented to an outside institution with progressive bilateral lower extremity pseudoclaudication and MRI findings of spinal stenosis, for which he underwent routine L3-5 laminectomy. The intraoperative course was complicated by a small incidental durotomy; primary repair was not possible, but egress of CSF resolved spontaneously, and the dura was lined with compressed gelatin sponge. On postoperative day 2, the patient developed confusion and agitation. Non-contrast head CT demonstrated SAH with intraventricular extension and prominent accumulation of blood products along the superior cerebellum and prominently along the bilateral posterior Sylvian fissures (Fig. 1a). CT angiogram was normal.

Noncontrast head CT demonstrating subarachnoid hemorrhage with intraventricular extension, a prominent accumulation of blood products along the superior cerebellum, as well as within the bilateral Sylvian fissures (a). MRI of the brain highlighting these same findings, with both gradient response echo (b) and FLAIR (c) sequence abnormalities capturing significant blood products over these same distributions

The patient was transferred to our neurosciences ICU for SAH management, which proceeded in accordance with standard protocols. MRI of the brain demonstrated a similar distribution of blood products on both GRE and FLAIR sequences, with no evidence for an alternative etiology underlying the patient’s condition (Fig. 1b–c). MRI of the spine demonstrated expected postoperative changes with no subdural and minimal, expected epidural blood products (not shown). His encephalopathy improved progressively over several days of supportive care, and the patient was transferred from the ICU in stable condition, with moderate cognitive impairment and preserved motor function.

On postoperative day 10, the patient was noted to have lost all lower extremity responses, with no other neurologic change. T1-weighted sagittal MRI of the lumbar spine demonstrated ventrolateral hyperintensity consistent with a new, large, acute, lumbar SDH, extending superiorly from the resection bed over L4-T12 (Fig. 2a). T2-weighted axial imaging of the lumbar spine just superior to the resection site identified an “inverted Mercedes sign” (Fig. 2b). At the level of the decompression, T2-weighted axial imaging also demonstrated a moderate pseudomeningocele with violation of the dural plane and anterior displacement of the neural elements, consistent with a CSF leak (Fig. 2c).

Subacute phase T1-weighted sagittal MRI of the lumbar spine demonstrated hyperintensity extending along the posterolateral aspect of the cauda equina from the resection bed superiorly, consistent with subdural hematoma (a). T2-weighted axial imaging of the lumbar spine just superior to the resection site was noteworthy for an inverted “Mercedes” sign, an uncommon but previously reported indication of spinal subdural hematoma (b). T2-weighted axial imaging through the level of the resection demonstrated a moderate-sized pseudomeningocele with violation of the dural plane and anterior displacement of the neural elements, consistent with a recurrent CSF leak (c)

The patient was taken urgently to the OR for decompression, during which a complex 1.5-cm lumbar durotomy was identified, associated with marked deflation of the dural tube and extensive spinal SDH. Primary repair was completed with silk suture and synthetic fibrin glue, and the patient was maintained in flat position for 24 h followed by progressive mobilization. No further evidence of CSF hypotension was observed, and the patient recovered partial bilateral lower extremity motor function but remained nonambulatory at time of dismissal to a skilled nursing facility.

Discussion

We present the first case of concomitant intracranial SAH and spinal SDH, theorized to share the underlying mechanism of CSF hypotension. These phenomena are likely driven by several factors acting in concert, with CSF volume loss leading to brain and spine sag, which in turn puts supercerebellar and spinal bridging veins under tension; simultaneously, a compensatory increase in venous volume produces vascular engorgement, further straining the dilated venous structures and predisposing them to avulsion or other injury [10, 30, 37–39]. Although the SAH and SDH observed in the present case are thought to be similarly derived, the clinical syndromes they produced are distinct and warrant discrete attention, as each has the potential to confound neurologic diagnosis in the postoperative period.

Intracranial SAH after spine surgery is extremely rare, with an estimated incidence of 0.8 % and approximately 40 cases reported to date [3, 18]. The mechanism underlying this phenomenon remains poorly understood; however, the most prominent hypothesis again relates brain sag and vascular engorgement from CSF hypotension to venous avulsion [3, 12, 18, 42, 45]. Supercerebellar veins appear to be the most vulnerable, and the majority of reported patients have demonstrated blood products overlying the superior cerebellar folia [3, 12, 18, 42, 45]. Other forms of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) including SDH, intraparenchymal hemorrhage (IPH), and intraventricular hemorrhage have also been documented in the setting of CSF hypotension and are hypothesized to follow from the same fundamental mechanism [5, 7, 8, 12, 18, 42, 45]. The proposed relationship between CSF hypotension and IPH finds further support in the association of postoperative subfascial drains and lumbar drains with remote hemorrhages, as either drainage device may inadvertently induce excessive CSF diversion [2, 14, 18, 29]. Still other reports have demonstrated remote ICH at the time of lumbar puncture or spinal epidural injection, or delayed ICH after placement of a lumboperitoneal shunt [27, 28, 33, 36].

Spinal SDH is an equally rare phenomenon, which has been documented as a complication of various interventions altering CSF dynamics including lumbar puncture, ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement, or craniotomy [10, 13, 20, 21, 34, 35]. A broad range of even less common etiologies has also been reported including spontaneous, posttraumatic, neoplastic, medication-induced, and vascular [15, 22, 26, 31, 34, 38, 40, 41, 43, 48].

One report of interest involves a patient with primary intracranial SAH after vertebral artery dissection, who developed symptomatic lumbar SDH causing unilateral foot drop, which the authors attributed to direct sedimentation of blood products from the craniocervical junction into a compressive hematoma within the thecal sac [46]. Although such a mechanism could potentially underlie the present case, the radiographic appearance is dissimilar, with our patient demonstrating more superior and longitudinal accumulation of blood products (as opposed to within the cul-de-sac). Notably, other reports from the radiology literature have shown that this “sedimentation sign” is observed in a significant fraction of SAH patients who undergo lumbar MRI, with the above-mentioned case representing the first and only instance of radiculopathy or myelopathy attributable to this anomaly—a stark contrast to our patient’s acute and severe myelopathy [9]. Finally, the large durotomy we observed would likely have siphoned blood out of the subdural space prior to clot formation. In this same vein, our case invites the question of whether routine postoperative epidural blood products and a large durotomy might predispose to development of a SDH. However, such flow would be retrograde to the expected CSF pressure gradients, which would prevent formation of a sufficient clot to cause mass effect and produce the patient’s precipitous weakness.

As in the present case, spinal SDH typically presents with bilateral lower extremity weakness, which may be accompanied by radicular pain, sensory changes, or bowel–bladder dysfunction [1, 13, 15, 20, 26, 27, 34]. When suspected, the diagnostic modality of choice is MRI, which shows time-dependent changes in blood products including T2 hyperintensity in the first 24 h, T2 hypointensity from 24 to 72 h, and ultimately progressive T1 hyperintensity over days three to seven [4, 16, 23, 24]. Early FLAIR and gradient-response echo abnormalities have also been observed and may prove most useful in the hyperacute and acute phase, when discrimination of an isointense hemorrhage is the most challenging [4, 23, 24]. Rare reports have also described an “inverted Mercedes sign” in which the SDH, CSF, and neural elements appear reminiscent of the marques logo [16, 17]. Although this sign was visualized on our patient’s imaging, our review of the literature suggests that it is highly inconsistent and not diagnostically reliable.

Treatment of spinal SDH is surgical decompression, particularly in the postoperative setting, although isolated reports have documented complete neurologic recovery after expectant management in cases of spontaneous or traumatic spinal SDH with mild neurologic signs [1, 10, 13, 15, 23, 25, 26]. Notwithstanding, these results are unproven, and in a patient with a new neurologic deficit localizing to a radiographic lesion, we advocate operative evacuation. This is especially important in cases such as ours, in which an underlying CSF leak is suspected, warranting direct inspection and repair.

Conclusion

Our case demonstrates a unique clinical history of concomitant intracranial SAH and spinal SDH, potentially linked by underlying CSF hypotension. Risk factors for the development of such hemorrhages are poorly defined but likely include intraoperative durotomy, suggesting that a watertight intraoperative repair should be attempted whenever possible [18]. A high index of suspicion is warranted in a patient who experiences an unexplained acute decline after spine surgery with durotomy, and we recommend a low threshold for proceeding to head CT or spinal MRI, as indicated by clinical symptoms. Patients with angiogram-negative SAH after spine surgery require ICU management and should be considered for advanced imaging, particularly if there is an associated history of durotomy or any symptoms concerning for CSF hypotension such as positional headache, tinnitus, or altered mental status. Although each of these entities is rare, they have the potential to be highly morbid, and early detection provides the best advantage for achieving a good neurologic outcome.

References

Al B, Yildirim C, Zengin S, Genc S, Erkutlu I, Mete A. Acute spontaneous spinal subdural haematoma presenting as paraplegia and complete recovery with non-operative treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2009.1599.

Andrews RT, Koci TM. Cerebellar herniation and infarction as a complication of an occult postoperative lumbar dural defect. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1312–5.

Bozkurt G, Yaman ME. Subarachnoid hemorrhage presenting with seizure due to cerebrospinal fluid leakage after spinal surgery. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2016;59:62–4.

Braun P, Kazmi K, Nogués-Meléndez P, Mas-Estellés F, Aparici-Robles F. MRI findings in spinal subdural and epidural hematomas. Eur J Radiol. 2007;64:119–25.

Burkhard PR, Duff JM. Bilateral subdural hematomas following routine lumbar diskectomy. Headache. 2000;40:480–2.

Cammisa FP Jr, Girardi FP, Sangani PK, Parvataneni HK, Cadag S, Sandhu HS. Incidental durotomy in spine surgery. Spine. 2000;25:2663–7.

Cevik B, Kirbas I, Cakir B, Akin K, Teksam M. Remote cerebellar hemorrhage after lumbar spinal surgery. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:7–9.

Chalela JA, Monroe T, Kelley M, Auler M, Bryant T, Vandergrift A, et al. Cerebellar hemorrhage caused by remote neurological surgery. Neurocrit Care. 2006;5:30–4.

Crossley RA, Raza A, Adams WM. The lumbar sedimentation sign: spinal MRI findings in patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage with no demonstrable intracranial aneurysm. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:279–81.

Domenicucci M, Ramieri A, Ciappetta P, Delfini R. Nontraumatic acute spinal subdural hematoma: report of five cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:65–73.

Francia A, Parisi P, Vitale AM, Esposito V. Life-threatening intracranial hypotension after diagnostic lumbar puncture. Neurol Sci. 2001;22:385–9.

Friedman JA, Ecker RD, Piepgras DG, Duke DA. Cerebellar hemorrhage after spinal surgery: report of two cases and literature review. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1361–3 discussion 1363-1364.

Gehri R, Zanetti M, Boos N. Subacute subdural haematoma complicating lumbar microdiscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:1042–5.

Honegger J, Zentner J, Spreer J, Carmona H, Schulze-Bonhage A. Cerebellar hemorrhage arising postoperatively as a complication of supratentorial surgery: a retrospective study. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:248–54.

Hung KS, Lui CC, Wang CH, Wang CJ, Howng SL. Traumatic spinal subdural hematoma with spontaneous resolution. Spine. 2002;27:E534–8.

Johnson PJ, Hahn F, McConnell J, Graham EG, Leibrock LG. The importance of MRI findings for the diagnosis of nontraumatic lumbar subacute subdural haematomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991;113:186–8.

Kalina P, Drehobl KE, Black K, Woldenberg R, Sapan M. Spinal cord compression by spontaneous spinal subdural haematoma in polycythemia vera. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71:378–9.

Kaloostian PE, Kim JE, Bydon A, Sciubba DM, Wolinsky JP, Gokaslan ZL, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage after spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19:370–80.

Khan MH, Rihn J, Steele G, Davis R, Donaldson WF, Kang JD, et al. Postoperative management protocol for incidental dural tears during degenerative lumbar spine surgery: a review of 3,183 consecutive degenerative lumbar cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2609–13.

Kim MS, Chung CK, Hur JW, Lee JW, Seong SO, Lee HK. Spinal subdural hematoma following craniotomy: case report. Surg Neurol. 2004;61:288–92.

Kim MS, Lee CH, Lee SJ, Rhee JJ. Spinal subdural hematoma following intracranial aneurysm surgery: four case reports. Neurol Med Chir. 2007;47:22–5.

Kim SH, Choi SH, Song EC, Rha JH, Kim SR, Park HC. Spinal subdural hematoma following tissue plasminogen activator treatment for acute ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2008;273:139–41.

Kirsch EC, Khangure MS, Holthouse D, McAuliffe W. Acute spontaneous spinal subdural haematoma: MRI features. Neuroradiology. 2000;42:586–90.

Küker W, Thiex R, Friese S, Freudenstein D, Reinges MHT, Ernemann U, et al. Spinal subdural and epidural haematomas: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects in acute and subacute cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142:777–85.

Kulkarni AV, Willinsky RA, Gray T, Cusimano MD. Serial magnetic resonance imaging findings for a spontaneously resolving spinal subdural hematoma: case report. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:398–400 discussion 400-391.

Kyriakides AE, Lalam RK, El Masry WS. Acute spontaneous spinal subdural hematoma presenting as paraplegia: a rare case. Spine. 2007;32:E619–22.

Lee AC, Lau Y, Li CH, Wong YC, Chiang AK. Intraspinal and intracranial hemorrhage after lumbar puncture. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:233–7.

Lee SJ, Lin YY, Hsu CW, Chu SJ, Tsai SH. Intraventricular hematoma, subarachnoid hematoma and spinal epidural hematoma caused by lumbar puncture: an unusual complication. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:143–5.

Miglis MG, Levine DN. Intracranial venous thrombosis after placement of a lumbar drain. Neurocrit Care. 2010;12:83–7.

Mokri B. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2001;1:109–17.

Morandi X, Riffaud L, Chabert E, Brassier G. Acute nontraumatic spinal subdural hematomas in three patients. Spine. 2001;26:E547–51.

Narotam PK, Jose S, Nathoo N, Taylon C, Vora Y. Collagen matrix (DuraGen) in dural repair: analysis of a new modified technique. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:2861–7 discussion 2868-2869.

Ozdemir O, Calisaneller T, Yildirim E, Altinors N. Acute intracranial subdural hematoma after epidural steroid injection: a case report. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30:536–8.

Russell NA, Benoit BG. Spinal subdural hematoma. A review. Surg Neurol. 1983;20:133–7.

Samuelson S, Long DM, Chou SN. Subdural hematoma as a complication of shunting procedures for normal pressure hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg. 1972;37:548–51.

Sasani M, Sasani H, Ozer AF. Bilateral late remote cerebellar hemorrhage as a complication of a lumbo-peritoneal shunt applied after spinal arteriovenous malformation surgery. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:77–9.

Schievink WI. Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:1345–56.

Schievink WI. Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks and intracranial hypotension. JAMA. 2006;295:2286–96.

Schievink WI, Maya MM. Cerebral venous thrombosis in spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Headache. 2008;48:1511–9.

Schievink WI, Maya MM, Moser FG, Tourje J. Spectrum of subdural fluid collections in spontaneous intracranial hypotension. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:608–13.

Schievink WI, Meyer FB, Atkinson JLD, Mokri B. Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks and intracranial hypotension. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:598–605.

Sciubba DM, Kretzer RM, Wang PP. Acute intracranial subdural hematoma following a lumbar CSF leak caused by spine surgery. Spine. 2005;30:E730–2.

Silver JM, Wilkins RH. Spinal subdural hematoma formation following ventriculoperitoneal shunting for hydrocephalus. Case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991;108:159–62.

Tafazal SI, Sell PJ. Incidental durotomy in lumbar spine surgery: incidence and management. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:287–90.

Thomas G, Jayaram H, Cudlip S, Powell M. Supratentorial and infratentorial intraparenchymal hemorrhage secondary to intracranial CSF hypotension following spinal surgery. Spine. 2002;27:E410–2.

Waldron JS, Oh MC, Chou D. Lumbar subdural hematoma from intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage presenting with bilateral foot drop: case report. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:E835–9.

Wang JC, Bohlman HH, Riew KD. Dural tears secondary to operations on the lumbar spine. Management and results after a two-year-minimum follow-up of eighty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1728–32.

Wurm G, Pogady P, Lungenschmid K, Fischer J. Subdural hemorrhage of the cauda equina. A rare complication of cerebrospinal fluid shunt. Case report. Neurosurg Rev. 1996;19:113–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Graffeo, C.S., Perry, A. & Wijdicks, E.F.M. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Spinal Subdural Hematoma Due to Acute CSF Hypotension. Neurocrit Care 26, 109–114 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-016-0327-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-016-0327-x