Abstract

The question of the extent to which EU institutions can grant powers to EU decentralised agencies has been the subject of inter-institutional and academic debate for decades. Only in 2014 did the Court of Justice itself settle the issue, confirming the constitutionality of ongoing agencification and allowing for its future development. The present article identifies a number of lessons which the EU legislature should draw from the Court’s Short-selling ruling. In addition a number of issues which have not yet been resolved by the Court but which may pose themselves in the future are identified. These relate to the nature of the discretion afforded to EU agencies, the nature of the acts which they adopt (in light of Articles 290 and 291 TFEU) and the new trend of allowing for direct delegations of power between national authorities and their EU counterparts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Today, the EU decentralised agenciesFootnote 1 constitute a significant part of the European Union (EU) administration, both in terms of resources and in terms of personnel.Footnote 2 For a long time the process of qualitative agencification, i.e. the trend of conferring increasingly significant tasks or powers on agencies,Footnote 3 proceeded timidly: since the EU Treaties (and before the EEC and EC Treaties) did not explicitly foresee or allow the establishment and empowerment of ‘secondary bodies’, the EU legislature moved on legally uncertain ground when it granted powers to a decentralised agency. This legal uncertainty continued until the 2014 Court ruling in the Short-selling case,Footnote 4 when the Court was asked for the very first time to scrutinise a decision granting powers to an EU agency. Through its judgment in Short-selling, the Court has offered the political institutions the constitutional framework within which the EU’s institutional architecture can be developed and executive powers may be granted to EU agencies. The present contribution provides a sketch of this framework, highlighting the key elements which the institutions will have to take into account when working out new legislation and identifying new contentious issues not addressed by the Court in Short-selling.

2 Constitutional obstacles to EU agencification

To put it simply, agencification was legally questionable pre-Short-selling in light of three main issues. Firstly, (pre-Lisbon) Article 4 EEC provided that the “tasks entrusted to the Community shall be carried out by the […] institutions” and Article 288 TFEU today still provides that to “exercise the Union’s competences, the institutions shall adopt regulations, directives, decisions, recommendations and opinions.” These provisions could be read as implying that only the institutions, but not other bodies, can exercise the EU’s competences.Footnote 5

Linked to this, but self-standing, is the requirement of upholding the institutional balance: if only the EU institutions can act on behalf of the EU, the decision of the EU legislature to empower an EU agency necessarily undermines the powers of another EU institution. However, even if the Treaties (implicitly) allow the establishment and empowerment of subsidiary bodies, it cannot be ruled out that the act of conferring powers on an agency may still undermine the prerogatives of one of the institutions. By way of illustration: the scope for establishing an independent European Cartel Office is limited (or non-existent) since Article 105 TFEU provides that “the Commission shall ensure the application of the principles laid down in Articles 101 and 102.” Similarly, establishing an agency competent to hear and determine questions referred for a preliminary ruling under Article 267 TFEU would undermine the prerogatives of the Court of Justice (Court) and the General Court.

Thirdly, assuming there is scope under the Treaties for establishing and empowering EU agencies (without violating the institutional balance), another question still is which kinds of powers may be conferred on or delegated to EU decentralised agencies. This is a perennial problem of delegation which every legal system is confronted with, and which was first addressed by the Court in the Meroni case of 1958.Footnote 6 For current EU agencification however, the question was whether this ECSC case dealing with a delegation of powers to private law bodies could be transposed to the EU legal framework to govern conferrals of power to public law bodies.Footnote 7

For decades, these issues were a source of contention between both the institutions and legal scholars but because EU agencification was based on a consensual approach between the EU institutions and the Member States,Footnote 8 they never escalated into genuine conflicts. The financial crisis, resulting in a qualitative step in EU agencification, changed this when the EU legislature decided to grant the European Securities and Market Authority (ESMA) an exceptional intervention power to regulate the practice of short-selling. In the legislative process, the UK was the only Member State in Council to vote against Regulation 236/2012Footnote 9 and subsequently challenged the Regulation’s validity before the Court, invoking, inter alia, the Meroni doctrine and the idea of institutional balance (although the latter was not invoked explicitly). The Court in the end rejected the UK’s action, thereby clarifying for the first time what the legal scope is for empowering EU decentralised agencies.

3 The Court’s ruling in Short-selling

Since the Court’s decision in Short-selling has been amply commented upon elsewhere,Footnote 10 only the most important elements in the Court’s ruling will be recalled here.

On the UK’s plea invoking the Meroni doctrine, the Court first confirmed that a conferral of powers by the EU legislature to an EU agency is indeed governed by Meroni. Subsequently the Court simplified the original Meroni doctrine by finding that it ‘in essence’ prohibits the delegation (or conferral) of discretionary powers.Footnote 11 Applying the doctrine in casu, the Court dismissed the UK’s plea by identifying a number of elements in the legislative framework (laid down by Regulation 236/2012)Footnote 12 that limit the ESMA’s scope of action to such an extent that its powers are “precisely delineated and amenable to judicial review in the light of the objectives established by [the legislature].”Footnote 13

In its third plea, the UK had argued that the legislature had violated Articles 290 and 291 TFEU when granting the contested power to the ESMA. The UK’s reasoning here was not as clear as it could be, albeit for evident reasons: reasoning its argument through, the UK reproached the Council and Parliament for granting an implementing power under Article 291 TFEU to an EU agency, whereas Article 291 TFEU only provides for the Member States, the Commission or the Council to adopt ‘implementing-type acts’. More precisely, Article 291 TFEU prescribes recourse to the Commission or Council when EU law has to be implemented uniformly. In essence, the UK was arguing that the legislature had violated the institutional balance by impinging on the Commission’s prerogative to implement EU law under the conditions of Article 291 TFEU. It should be clear however that this would not have advanced the UK’s case, since that Member State’s actual aim was to reserve the implementation of EU financial regulation to its own authorities. Put differently, it is not that the UK did not want an EU agency to implement EU law, it simply did not want any EU authority to implement EU law.

The Court also dismissed this plea by firstly finding that Articles 290 and 291 TFEU constitute an open framework to which the legislature is not restricted and,Footnote 14 secondly, by finding that the ESMA’s contested power did not correspond to the powers envisaged in Articles 290 and 291 TFEU.Footnote 15

Finally, the UK had also argued that if the ESMA’s contested power would result in binding decisions addressed at individual market operators, the legislature could not have based its regulation on Article 114 TFEU, since ‘adopting individual measures addressed at natural or legal persons’ cannot be qualified as ‘harmonisation’. While the AG found that Article 114 TFEU could indeed not serve as a legal basis,Footnote 16 the Court upheld the regulation by recalling its well-established jurisprudence on Article 114 TFEU. A key feature of this jurisprudence is the broad discretion afforded to the EU legislature in choosing the most appropriate method of harmonisation.

4 Take home message from Short-selling

To a great extent, the Court’s ruling in Short-selling may be read as a drafting manual for the Commission and legislature when they contemplate granting further powers to EU agencies.Footnote 17 Should they wish to grant further (significant) powers to EU agencies, they would be well-advised to pick up on the reasoning developed by the Court.

4.1 Agencies and Meroni

Thus, any such power should be ‘precisely delineated’ and the Court offers us a number of elements which contribute to satisfying this condition. Going beyond the case-specifics of Short-selling, a power will be held to be precisely delineated when (i) the conferral of powers is exceptional, (ii) the agency’s powers are embedded in decision-making procedures involving other actors, and (iii) the agency acts pursuant to pre-defined criteria.Footnote 18

Granting significant powers to EU agencies should be exceptional, since implementing and/or enforcing EU law is typically a task for the Member States’ administrations. As a rule, EU agencies should play a supporting role in this process and if they are empowered to take up primary responsibility in this regard, the EU legislature should take care to properly set out the reasons for this.Footnote 19 Secondly, the Court in Short-selling emphasised that the ESMA could not act autonomously but had to consult other bodies before taking a decision. Remarkably, the Court did not seem to mind that these consultations were non-binding. The EU legislature might want to pick up on this when in the future it contemplates a significant conferral of powers to an EU agency. Prescribing a mandatory consultation in the agency’s decision-making procedure may shield the conferral of powers from contestation on the grounds of the Meroni doctrine. Lastly and most importantly, the Court in Short-selling stressed the fact the ESMA was ‘limited’ in its powers because it had to act on pre-defined criteria laid down both in the legislative regulation and in the Commission’s delegated acts prescribed by the legislative regulation. Crucially, the Court did not seem to take issue with the vagueness of these pre-defined criteria, which could actually be read as proof of the ESMA’s discretionary power. By stressing that pre-defined criteria are laid down for the agency to act upon, the political institutions may in the future again shield conferrals of power to EU agencies from contestation, regardless of how vague these criteria are, i.e. regardless of how much discretion they leave to the agency.

4.2 Agencies and Articles 290 and 291 TFEU

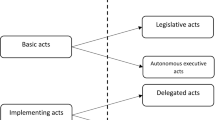

Short-selling clarified that it is possible to grant EU agencies ‘implementing’ powers without upsetting the Treaty framework on delegated and implementing acts laid down in Articles 290 and 291 TFEU, but it does not immediately clarify how the EU legislature can choose between granting a power to the Commission or to an EU agency. This difficult question actually links up with the (equally problematic) question of how the EU legislature can know whether to grant the Commission a delegated power (under Article 290 TFEU) or an implementing power (under Article 291 TFEU). Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, the Court has solved the latter question by finding that the legislature has a discretion in granting an executive power to the Commission either in the form of an implementing (291) or delegated (290) power.Footnote 20

In Short-selling however, the Court does not explicitly find that the legislature has a discretion in choosing between giving an executive power to the Commission or to an agency. Instead it branded the ESMA’s power as qualitatively different from the powers envisaged in Articles 290 and 291 TFEU. Questionable as this finding may be,Footnote 21 the lesson for the EU legislature is to stress the special nature of the powers which it would want to confer on an EU agency. To put it simply, the implementing power of the Commission under Article 291 TFEU is a general implementing power, whereas the implementing powers which may be entrusted to an agency require not general expertise but a high degree of professional or technical expertise lacking in the ‘generalist’ European Commission. Presenting an executive power granted to an EU agency in this way will then shield it from contestation on the basis of Article 291 TFEU.

What about the power under Article 290 TFEU? The Court in Short-selling itself does not distinguish between Articles 290 and 291 TFEU, and hence both could be entrusted to EU agencies but it nonetheless seems doubtful that the legislature could grant an agency the power to amend or supplement formal legislation. Not so much because EU agencies are less democratically legitimate than the European Commission,Footnote 22 as suggested by AG Jääskinen,Footnote 23 but because the very act of altering formal legislation would seem to require the intervention of an authority vested in the Treaties, as Lenaerts notes.Footnote 24 Lenaerts further argues that delegated acts, since they are of quasi-legislative nature, would ipso facto require the exercise of discretionary powers and would therefore in any case violate the (Meroni) requirement that an agency can only exercise precisely delineated powers. However, this seems more questionable since the discretion afforded to the Commission depends on how the legislature has defined the mandate. Already today examples exist whereby the Commission is granted a power under Article 290 TFEU without having any discretionary margin in adopting the required delegated acts.Footnote 25

Thus proceeding purely on the basis of Short-selling, granting an agency the power to amend or supplement EU legislation would seem possible but ill-advised. The power to amend or supplement would have to be precisely delineated and the legislature would have to show that it is not necessary (or that it would even be counterproductive) to empower the Commission under Article 290 TFEU. In any event, this discussion seems deprived of much practical relevance, now that the Court has blurred the demarcation line between Articles 290 and 291 TFEU (cf. supra). Instead of arguing why an EU agency ought to be granted the power to supplement formal legislation, the EU legislature can avoid these difficulties by presenting the power conferred to an EU agency as a ‘mere’ implementing power, something which the Court clearly sanctioned in Short-selling.

4.3 Agencies and Article 114 TFEU

Lastly, part of the take home message of Short-selling relates to the use of Article 114 TFEU as a legal basis in agencification. In casu, the UK argued that Article 114 TFEU could not be relied upon to empower an EU agency to adopt individual measures addressed to private parties. The Court also rejected this plea, thereby further elaborating its Article 114 TFEU jurisprudence. In cases such as Smoke Flavourings and General Product Safety Footnote 26 the Court had already sanctioned recourse to the harmonisation clause to establish a centralised (EU) decision-making procedure and to adopt both general as well as individual decisions. The question therefore was whether these individual measures could also be addressed to private parties rather than Member States (as in General Product Safety) and whether the essential elements informing the decision-making in the centralised (EU) procedure were laid down in the formal legislative act (as required under Smoke Flavourings).Footnote 27 The Court answered the first question positivelyFootnote 28 but did not address the second question explicitly since this requirement was de facto already covered by the Court’s conclusion that ESMA did not exercise a discretionary power. The take home message for the legislature is reassuring since the Court several times stressed that the legislature has discretion in choosing the most appropriate method of approximation and heavily relied on the recitals in the legislative act to perform its scrutiny.Footnote 29 Short-selling as the provisionalFootnote 30 culmination of the Court’s jurisprudence on Article 114 TFEU therefore results in a sound constitutional basis and henceforth preferable legal basis for future agencification.

5 Current and future issues in agencification

Although Short-selling constitutes an important judicial sanctioning of agencification it should be clear that it does not solve all legal issues pertaining to the phenomenon. Three issues will be discussed further: (i) the question of discretion exercised by EU agencies, (ii) the question of institutional balance and (iii) the question of an upward delegation (rather than a legislative conferral) of powers to EU agencies.

5.1 Which discretion is prohibited for EU agencies?

Following Short-selling the core of the Meroni doctrine, i.e. the prohibition to grant discretionary powers, (still) applies to EU agencies. Yet, when precisely a power should be qualified as ‘discretionary’ and thus non-delegatable or non-conferrable to EU agencies, remains unclear. As noted above, the Court’s conclusion in Short-selling that the ESMA’s power under Article 28 of Regulation 236/2012 was non-discretionary is very much debatable but should be accepted as the standard for further agencification. At first sight, the Court upholding the Meroni doctrine in this regard sits uneasily or even conflicts with the General Court’s jurisprudence in which it has recognised a broad discretion on the part of the authorities of the EU, especially in relation to the assessment of complex scientific and technical facts. The General Court consistently confirms this jurisprudence also in relation to the EU agencies, without therefore making any distinction, among the ‘EU authorities’, between EU institutions and EU secondary bodies.

The discretion as thus recognised by the General Court does not only extend to the question of which measures ought to be taken but also to the finding of the basic facts (upon which an authority acts).Footnote 31 The General Court’s most far-reaching statement on the nature of this discretion can be found in the Rütgers case in which it noted: “it must be acknowledged that the ECHA has a broad discretion in a sphere which entails political, economic and social choices on its part, and in which it is called upon to undertake complex assessments. The legality of a measure adopted in that sphere can be affected only if the measure is manifestly inappropriate having regard to the objective which the legislature is seeking to pursue.”Footnote 32 So how can this kind of discretion be reconciled with the prohibition under the Meroni doctrine of granting discretionary powers to EU agencies?

The answer lies is in the fact that the ECHA’s discretion sanctioned in Rütgers is something different from the discretionary powers prohibited under Short-selling. Originally it could be said that both were indeed incompatible, since under the original Meroni ruling, powers were only deemed to be executive or non-discretionary when a body’s decisions were “the result of mere accountancy procedures based on objective criteria laid down by the [delegating authority].”Footnote 33 An agency would thus be relegated to a kind of calculator, mechanically connecting a certain input to output (a decision).Footnote 34 In Short-selling however, the Court focused on another finding in the original Meroni ruling, namely that a discretionary power “may, according to the use which is made of it, make possible the execution of actual economic policy.”

On the scale from ‘mere accountancy procedures’ to ‘the execution of actual economic policy’ the Court in Short-selling thus chose to interpret ‘discretionary powers’ restrictively, allowing an EU agency to exercise the kind of ‘executive discretion’ sanctioned by the General Court in Rütgers, since such a discretion still does not allow the agency to develop a policy of its own. After all, it should be noted that the dispute in Rütgers revolved around the question whether anthracene oil (paste) should, as a substance, be deemed of very high concern such as to warrant its inclusion on the candidate list of substances for inclusion in Annex XIV of the REACH Regulation.Footnote 35 The policy of regulating dangerous chemicals and limiting or phasing out their use has been clearly established by the legislature in the REACH Regulation. The question of whether a chemical is dangerous is a scientific one for the ECHA to address and the Court rightly declined to second guess the scientific assessment, instead emphasising the ECHA’s discretion.

Still, the confusing part in Rütgers is the Court’s reference to the ‘political, economic and social choices’ which the ECHA is allegedly entitled to make. The reference to these choices was superfluous since ECHA only adopts a scientific decision. This part of the judgment is actually an example of sloppy drafting: the Court simply copy-pasted the standard provision it uses when it scrutinises acts of the EU legislature or the Commission, stressing the discretion afforded to the institutions (including the legislature).Footnote 36 It thus ignored the fact that EU agencies are not institutions of the EU, let alone that they have the legitimacy of the formal legislature.

To sum up, the kind of discretion sanctioned by the General Court in cases such as Rütgers is an executive discretion. It falls somewhere between a purely executive power (referred to by the Court in the original Meroni ruling) and the discretion which the Commission may exercise under Article 290 and 291 TFEU. Fitting it in the larger framework of EU-rulemaking, it is up to the EU legislature to make political, economic and social choices and only the legislature can decide on the essential elements of EU legislation. Next, the Commission can make political, economic and social choices when it implements, supplements or amends EU legislation while fully respecting the essential elements and the essential aimsFootnote 37 of that legislation. Finally, EU agencies can exercise an executive discretion when implementing EU law. In this, at least the same substantive limits as those applicable to the Commission (under Article 291 TFEU) ought to apply but without the agency being empowered to make political, economic or social policy choices.

5.2 The question of institutional balance

One of the issues ignored by the Court in the Short-selling case was the repercussions of its ruling on the institutional balance. After all, the Court effectively ruled that the legislature can work outside the framework of Articles 290 and 291 TFEU, granting ‘executive-type’ powers to bodies (EU agencies) not foreseen in those Articles. This begs the question of how this affects the prerogatives of the EU institutions that are mentioned in those Articles. More concretely, it can be argued that the Commission (or exceptionally the Council) derives a prerogative from Article 291(2) TFEU to implement EU law when uniform conditions therefor are required. Similarly, it is a prerogative of the Commission to amend or supplement EU legislation on its non-essential elements whenever the formal legislature has opted not to do so itself. In Short-selling the Court seemingly opens up these powers to the EU agencies without putting checks on the legislature’s choice to forgo the options provided by Articles 290 and 291 TFEU.

In theory it thus has become easier for the legislature to grant executive powers to EU agencies than to the Commission since granting powers to the Commission is governed by the (heavy) framework of Articles 290 and 291 TFEU while no similar such a framework is in place for empowering EU agencies.Footnote 38 Will the EU legislature then not ignore the Commission’s prerogatives in the future? In light of the political context this would appear to be a rash conclusion. After all, EU agencification is generally based on a broad inter-institutional consensus,Footnote 39 where Parliament and Council will be very mindful of the Commission’ sensitivities. Any new significant power will also have to be proposed by the Commission which can thus exercise a form of control over which powers are entrusted to EU agencies. The legislative act, the legality of which was contested by the UK in Short-selling, is an illustration of this: the Commission itself originally proposed to grant this power to the ESMAFootnote 40 and the power is a very specific and exceptional one. While Short-selling does not exclude the legislature conferring significant executive powers to EU agencies rather than to the Commission, political reality means that any such powers will only be granted if there is a consensus between the three political institutions.Footnote 41

A second question is whether the agencies’ involvement in the drafting of implementing and delegated acts, formally adopted by the Commission, respects the institutional balance. Indeed, the Commission’s formal powers could de facto be hollowed out to such an extent that the Commission is divested of its prerogative to adopt implementing and delegated acts. Although the ESAs have the most far-reaching powers in this regard, which Craig criticises,Footnote 42 this issue is not restricted to the ESAs. Michel notes that the Commission’s prerogatives under Articles 290 and 291 TFEU only cover the adoption of delegated and implementing acts but do not grant an exclusive right on the drafting of such acts to the Commission. The involvement of agencies is then possible but the Commission should have complete liberty to alter the drafts presented to it, which is not the case when the ESAs draft delegated acts for the Commission.Footnote 43 Although not so much linked with the issue of institutional balance, it may further be noted that the procedures prescribed by the ESAs’ establishing acts for the adoption of implementing acts also deviate from the default rules laid down in the Comitology regulation.Footnote 44 If the latter may be qualified as a piece of organic EU law,Footnote 45 this may put in doubt the legality of the procedures foreseen in the ESAs’ regulations.

5.3 The question of upward delegations

Until the current phase in EU agencification, the powers granted to EU agencies were entrusted to them by the EU institutions. In this regard, part of the debate has revolved around the questions of how these empowerments ought to be qualified: the EU legislature cannot delegate powers which it does not possess itself (this also flows from Meroni) and it has thus been argued that the legislature is therefore conferring powers, whereas only the Commission could delegate executive powers to an EU agency. Some authors have argued that since the EU agencies’ powers were never exercised by the Commission in the first place but by the Member States’ administrations, agencification entails neither conferral nor delegation but a ‘Europeanization’ of executive power even if powers are formally granted by EU institutions.Footnote 46

More recently, the EU legislature has explicitly provided in a number of legislative acts that national authorities can further delegate powers to EU agencies on a bilateral basis. This is for instance foreseen in Article 28 of the establishing acts of the ESAs, even if only in the case of ESMA this option has been used in practice. The framework governing these delegations as set out in Article 28 is however rather limited. A similar delegation provision may be found in the proposal for a new EASA regulation which provides that the EASA “shall only agree to the transfer of responsibilities […] when it is satisfied that it can effectively exercise the transferred responsibility in compliance with this Regulation and the delegated and implementing acts adopted on the basis thereof.”Footnote 47 While this adds a further requirement before the agency can consent to the delegation, it should be clear that this limitation is still incomplete since it does not refer to compliance with the Treaties.

How should such a transfer be evaluated under Article 291 TFEU? Since it concerns powers of national authorities (Article 291(1) TFEU), the prerogatives of the Commission need not be concerned unless it is shown that the agency is actually being asked to implement EU law under uniform conditions. Since the powers would be transferred by national authorities, the Meroni doctrine would not act as a limit in line with Spain v. Parliament and Council.Footnote 48 This would only be different if the Court in its future jurisprudence gives effect to the objectivised test under Article 291(2) TFEU.Footnote 49 Pre-Lisbon, the EU legislature’s choice to grant the Commission with an implementing power (in the strict sense) was facultative (as confirmed early on in Köster):Footnote 50 the legislature was free to confer (or not) an implementing power on the Commission. The Treaty of Lisbon altered this, at least on paper, ruling out any legislative discretion: if uniform conditions are required, the legislature must confer an implementing power on the Commission.

Whether such a transfer would have to conform to Meroni thus depends on how the transferred power is conceptualised and how Article 291(2) TFEU is read. Interpreting the latter broadly so that it catches the transferred power would mean that the EU legislature allows national authorities to transfer powers which should have been conferred on the Commission (or exceptionally the Council) in the first place. Hence Meroni should apply, to prevent it from being circumvented. If the transferred power is conceptualised as different from the power in Article 291(2) TFEU (for instance because of a narrow reading of the latter), one could argue that powers are not delegated (or conferred) downwards from the Commission (or legislature) to EU agencies but upwards from the Member States. If this reasoning were to be upheld, the Meroni doctrine would not apply since no conferral or delegation from an EU authority is at issue.

Finding that Meroni would not apply of course would not mean that any kind of powers could be delegated from a national authority to an EU agency. Should the EU legislature wish to inscribe this mechanism in further legislative acts, care should be taken that the institutional balance is not upset. This would mean, inter alia, that the agency’s mandate as defined by the legislature should not de facto be amended through a bilateral delegation agreement between the agency and a national authority. Whether it is sufficient in this regard that the agency (Board) agrees itself with the delegation (without an agreement from the Commission or legislature) then remains doubtful.

6 Conclusion

In its Short-selling ruling the Court applied and interpreted the Meroni doctrine and Articles 290 and 291 TFEU in such a way as to sanction current and future EU agencification. The ruling gives a sound basis to the political institutions to grant further powers to EU agencies, further constructing the EU’s integrated administration. This is not to say that all legal questions surrounding the institutional phenomenon of agencification have been resolved but the Court gave its judicial blessing and in practice agencification has always proceeded based on a political consensus between the Commission, Council and Parliament. It is also because of this consensus that the limits of the new Short-selling doctrine will not immediately be tested: testing these limits would require a new qualitative leap in agencification which could probably only come about when the EU is faced with a crisis similar to the financial- and euro-crises. While the 2015–2016 migrant crisis has resulted in an upgrade of Frontex’ powers, its (remarkable) increase in powers falls short of being qualified as resulting in an autonomous (from both the Member States and the EU institutions) operational power. That said, legal questions in relation to (i) the precise nature of the discretion which agencies can exercise, (ii) how the acts which they adopt relate to the acts foreseen in Article 290 and 291 TFEU and (iii) which delegation regime applies to direct upward delegations from a national authority to its EU counterpart, remain unresolved. These issues may end up before the Court but even if they do not, the political institutions would be well advised not to merely glance over them when these present themselves during legislative negotiations.

Notes

Although an official definition is lacking, the EU decentralised agencies may be defined as permanent bodies under EU public law, established by the institutions through secondary legislation and endowed with their own legal personality. See Chamon [2], p. 10.

For instance, between 2006 and 2016 the subsidies from the EU budget to the EU agencies has more than tripled.

Chamon [2], pp. 45–46.

Case C-270/12 UK v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2014:18.

See Chamon [2], p. 135.

Case 9/56 Meroni, EU:C:1958:7.

Chamon [4], p. 383.

Chamon [2], p. 119.

Regulation 236/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2012 on short selling and certain aspects of credit default swaps [2012] OJ L86/1.

Case C-270/12 UK v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2014:18, para. 42.

Ibid., paras 46–51.

Ibid., para. 53.

Ibid., paras 78–79.

Ibid., para. 83.

Opinion of AG Jääskinen in Case C-270/12 UK v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2013:562.

On the Court’s jurisprudence as a ‘drafting guide’ for the EU legislature, see Weatherill [15].

Chamon [2], p. 247.

Note that in Short-selling the ESMA’s intervention powers were exceptional in the sense that the ESMA will only be competent when the Member States’ authorities do not take sufficient action to address serious threats to the stability and integrity of financial markets. In this regard, the Court did not take issue with the fact that it is up to the ESMA itself to decide whether Member States’ authorities have taken sufficient action.

See Case C-427/12 Commission v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2014:170; Case C-88/14 Commission v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2015:499.

After all, nothing prevents the EU legislature from setting up an EU agency that is subject to greater democratic control than the European Commission is.

Opinion of AG Jääskinen in Case C-270/12 UK v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2013:562, para. 85.

Lenaerts [8], pp. 762–763.

See for instance Article 9d of Directive 1999/62 which allows the Commission to adapt, by way of delegated acts, Annex 0 of the Directive to the Union acquis and Article 3(2) of the same Directive which allows the Commission to amend (without referring to a delegated act) the list of national taxes in Article 3(1) when a Member States notifies the Commission of a change in its tax system. See Directive 1999/62/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 1999 on the charging of heavy goods vehicles for the use of certain infrastructures [1999] OJ L 187/42.

See Case C-66/04 UK v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2005:743; Case C-359/92 Germany v Council, EU:C:1994:306.

Chamon [4], p. 388.

Case C-270/12 UK v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2014:18, para. 107.

Ibid., paras 102, 103, 105, 109, 114–115.

Following Short-selling the Court’s jurisprudence on Article 114 TFEU has of course further developed. See notably Case C-358/14 Poland v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2016:323.

See e.g. Case T-135/13 Hitachi Chemical Europe e.a. v ECHA, EU:T:2015:253, paras 52–53; Case T-115/15 Deza v ECHA, EU:T:2017:329, paras 163–164.

Case T-94/10 Rütgers v ECHA, EU:T:2013:107, para. 133.

Case 9/56 Meroni, EU:C:1958:7, p. 153.

Note however that the ESMA’s power to fine as laid down in Regulation 648/2012 is exactly elaborated in such a way, see Article 65 and Annexes I and II of the Regulation.

The substances included in Annex XIV are substances for which an authorisation is required in order to be used or to be put on the market for use.

See e.g. Case C-358/14 Poland v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2016:323, para. 79; Case T-100/15 Dextro Energy v Commission, EU:T:2016:150, para. 30.

See Case C-65/13 Parliament v Commission, EU:C:2014:2289, para. 43.

See above, fn. 8.

See COM (2010) 482 final.

See however ESMA’s power to fine credit rating agencies under Regulation 1060/2009 as amended by Regulation (EU) 513/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2011 [2011] OJ L 145/30. In its original proposal, the Commission had proposed to grant itself this power following a recommendation from the agency, but the European Parliament amended this. See Article 36a in COM (2010) 484 final.

Craig [6], pp. 195–198.

Michel [10], pp. 227–236.

Regulation (EU) 182/ 2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 February 2011 laying down the rules and general principles concerning mechanisms for control by Member States of the Commission’s exercise of implementing powers [2011] OJ L 55/13.

The LIFE case could be read in this way as suggested by Schütze. See Case C-378/00 Commission v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2003:42; Schütze [12], p. 678.

See Article 53(3) of the regulation proposed by COM (2015) 613 final.

Case C-146/13 Spain v Parliament & Council, EU:C:2015:298, para. 87.

On this objectification, see Chamon [3], p. 1508.

Case 25/70 Köster, EU:C:1970:115.

References

Bertrand, B.: La compétence des agences pour prendre des actes normatifs; le dualisme des pouvoirs d’exécution. Revue trimestrielle de droit européen (2015)

Chamon, M.: EU Agencies: Legal and Political Limits to the Transformation of the EU Administration. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2016)

Chamon, M.: Institutional balance and Community method in the implementation of EU legislation following the Lisbon Treaty. Common Mark. Law Rev. (2016)

Chamon, M.: The Empowerment of Agencies under the Meroni Doctrine and art. 114 TFEU: Comment on United Kingdom v Parliament and Council (Shortselling) and the Proposed Single Resolution Mechanism. Eur. Law Rev. (2014)

Clément-Wilz, L.: Les agences de l’Union européenne dans l’entre-deux constitutionnel. Revue trimestrielle de droit européen (2015)

Craig, P.: Comitology, rulemaking and the Lisbon settlement—tensions and strains. In: Bergström, C.F., Ritleng, D. (eds.) Rulemaking by the European Commission—The New System for Delegation of Powers. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2016)

Kohtamäki, N.: Die ESMA darf Leerverkäufe regeln. Europarecht (2014)

Lenaerts, K.: EMU and the EU’s constitutional framework. Eur. Law Rev. (2014)

Martucci, F.: Les pouvoirs de l’Autorité européenne des marchés financiers à l’épreuve du droit constitutionnel de l’Union. Rev. Aff. Eur. (2014)

Michel, K.: Institutionelles Gleichgewicht und EU-Agenturen. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin (2014)

Ohler, C.: Rechtsetzungsbefugnisse der Europäischen Wertpapier- und Marktaufsichtsbehörde (ESMA). JuristenZeitung (2014)

Schütze, R.: ‘Delegated’ Legislation in the (New) European Union: A Constitutional Analysis. Mod. Law Rev. (2011)

Skowron, M., Kapitalmarktrecht: Rechtmäßigkeit der Eingriffsbefugnisse der ESMA nach Art. 28 Leerverkaufsverordnung. Eur. Z. Wirtsch.r. (2014)

Van Cleynenbreugel, P.: Meroni circumvented? Article 114 TFEU and EU Regulatory Agencies. Maastricht J. Eur. Comp. Law (2014)

Weatherill, S.: The Limits of Legislative Harmonisation Ten Years After Tobacco Advertising: How the Court’s Case Law Has Become a “Drafting Guide”. Ger. Law J. (3) (2011)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Merijn Chamon, Post-doctoral assistant at the Ghent European Law Institute, Ghent University (Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence); Visiting Professor at the University of Antwerp.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chamon, M. Granting powers to EU decentralised agencies, three years following Short-selling . ERA Forum 18, 597–609 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-017-0486-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-017-0486-z