Abstract

Reasons underlying retractions of papers authored by the Iran-affiliated highly cited researchers (HCRs) have not been documented. Here, we report that 229 of the Iran-affiliated researchers were listed by the Clarivate Analytics as HCRs. We investigated the Retraction Watch Database and found that, in total, 51 papers authored by the Iran-affiliated HCRs were retracted from 2006 to 2019. Twenty-three of the 229 HCRs (10%) had at least one paper retracted. One of the listed HCRs had 22 papers retracted; 14 of the 23 (60.8%) had only one paper retracted. Among the 51 retracted papers, three had been authored by two female authors. Eight (16.8%) retracted papers had international co-authorships. The shortest and longest times from publication to retraction were 20 and 2610 (mean ± SD, 857 ± 616) days, respectively. Of the 51 papers, 43 (84%) had a single reason for retraction, whereas eight had multiple reasons. Among the 43 papers, 23 (53%) were retracted due to fake peer-review, eight (19%) were duplications, six (14%) had errors, four (9%) had plagiarism, and two (5%) were labelled as “limited or no information.” Duplication of data, which is easily preventable, amounted to 27%. Any publishing oversight committed by an HCR may not be tolerated because they represent the stakeholders of the scientific literature and stand as role-models for other peer researchers. Future policies supporting the Iranian academia should radically change by implementation of educational and awareness programs on publishing ethics to reduce the rate of retractions in Iran.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Each year, Clarivate Analytics (formerly called “The Intellectual Property and Science Business of Thomson Reuters”) identifies those international researchers who have published multiple highly cited scientific papers, ranking in the top 1% after attracting citations in one of the 21 fields of research (Web of Science Group 2020b). The list of the “Highly Cited Researchers” (HCRs) is based on the bibliometric parameters used by the Web of Science (Web of Science Group 2020a). Becoming an HCR is a prestigious achievement for the researchers, their institutions, and their countries. For example, China and Australia have increased their HCR ranking by threefold from 2014 to 2019, a ranking that had not been achieved previously even by the United States (Clarivate Analytics 2019). Being recognized as an HCR by the Clarivate Analytics is an aspiration for many Iranian researchers and may lead to securing grants, tenured positions, and promotions. Moreover, affiliation of multiple HCRs to a single university likely achieves a higher ranking for their institutions in a global system of university rankings, for instance, the Shanghai ranking (Docampo 2010). Universities and research institutions tend to appoint HCRs or confer them secondary or honorary appointments to boost performance or ranking, and highly cited researchers are generally found to be overseeing high-ranking universities (Docampo 2010; Goodall 2009).

Retraction of a published paper is an important means of identifying and earmarking those scientific papers that, for example, may have presented erroneous or fraudulent data (Fanelli 2013). The reasons for high numbers of retractions have been investigated in diverse scholarly disciplines, including surgery, biomedical sciences, and engineering.

Before studying retractions of the papers published by the Iran-affiliated HCRs, we mention the historical event that preceded the inception of retractions. An English-written paper titled “Treatise upon Electricity” was the first to be retracted in 1755 when Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London discovered its errors (Wilson 1997). Thereafter, paper retractions were purposed as a mechanism for self-correcting the scientific literature (Alberts et al. 2015; Jamieson 2018). Contrarily, this self-correcting system had been argued to be a “myth” (Stroebe et al. 2012). We add that retractions may also misguide the public perception about the scientists and their discoveries. Nevertheless, the total number of retracted papers has increased with time, reaching thousands in 2020. Meanwhile, advances in information technology has allowed the journals, their editors, or publishers to detect malpractices such as plagiarism or duplication (Steen et al. 2013; Gasparyan et al. 2017), which may lead to retractions.

The Iranian universities and research institutions have produced a large number of papers over the past 35 years (Kolahi and Abrishami 2013; Ataie-Ashtiani 2017). Although intensely criticized, mindsets such as “publish or perish” among the Iran-affiliated researchers likely have played a role in increasing the number of papers published yearly. Meanwhile, some damning 2016 reports published by Nature and Science raised ethical concerns pertaining the burgeoning number of Iran-affiliated publications (Callaway 2016; Oransky 2018; Rezaee-Zavareh et al. 2016; Stone 2016). Purportedly, a shady market of ghost-writers was alleged to be helping the Iran-affiliated researchers to publish papers while, on average, 14 per 10,000 Iran-affiliated papers were retracted yearly (Oransky 2018).

The reasons for retractions may include fake peer-review, plagiarism, data duplication, data falsification or fabrication, conflict of interest, authorship conflicts, and advertent or inadvertent errors (Al-Hidabi and Teh 2019; Budd et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2019). Although the rising number of retractions has alerted the publishers to identify the questionable papers (Fanelli 2013), the large volume of retracted papers is still a serious concern (Fang et al. 2012; Steen et al. 2013). Continually citing and treating the retracted papers as legitimate sources of scientific knowledge (Budd et al. 1998) are greatly concerning not just in Iran but globally, too. Subsequent nationally adopted strategies by the Iranian ministry of Science, Research and Technology and ministry of Health and Medical Education have aimed to reduce and suppress any publication with malpractices under a zero-tolerance policy.

Iranian HCRs have inevitably participated in increasing the number of Iran-affiliated papers (Isna News Agency 2019). The Clarivate Analytics had listed 229 Iran-affiliated researchers as HCRs, indicating an almost fivefold increase within a six-year period (Tabnak Professional News Site 2020; Student News Network [Khabarguzari Daneshjoo] 2020). Recognition as an HCR by Clarivate Analytics may precede some benefits, such as grants, promotions, and tenured positions in Iran. Therefore, such a recognition would be the ultimate goal of many Iranian researchers.

No retractions or a low number of retracted publications attributed to any country’s scientific community may indicate ethical and responsible conduct of academic research. Because HCRs represent aspiring beacons of the scientific knowledge in their respective fields and nations—and the world—many expect them to have no retractions. The number of retracted Iran-affiliated papers has doubled between 2013 and 2019, from 60 to 117, respectively (http://retractiondatabase.org/RetractionSearch.aspx?) (Oransky 2018; Brainard and You 2018). The most common reasons for retractions attributed to papers published by HCRs, particularly the Iran-affiliated HCRs, had not been documented. We aimed to reveal the most common reasons for retractions of the papers authored by Iran-affiliated HCRs.

Methods

Two independent operators searched the Persian and English listings to confirm the identity of the 229 Iran-affiliated HCRs who were listed by the Clarivate Analytics. To find the retracted papers authored by Iranian HCRs, we searched the HCRs’ names on the Retraction Watch Database (RWD version 1.0.5.5; http://retractiondatabase.org/RetractionSearch.aspx?) with the affiliation term “Iran”. We accessed this version of RWD in December 2020 before submitting this work. Our search window included 2006–2019. After finding the retracted papers attributed to an HCR, we double-checked each retracted paper in their corresponding journal to confirm the issuance of a retraction notice. Our search enabled finding both retracted original papers and conference proceedings indexed in RWD. If we found any retracted abstract, we classified them as conference proceedings; we classified the clinical studies as original papers. Generic reasons for retractions categorized by RWD included data fabrication or falsification, errors (errors in analysis, unreliable data, or irreproducible data), fake peer-review, authorship disputes, limited or no information, duplicate publications (duplication of text, tables, or images), or errors by a publisher or a journal. The publication and retraction dates, type of papers, reasons for retractions, disciplines of the retracted papers, the number of co-authors, and international co-authorships were the queries we considered. The 2019 impact factors for the corresponding journals were documented after referring to the Journal Citation Reports. The Journal Citation Reports, which is published annually by Clarivate Analytics, helps academic researchers and scientists to find legitimate academic journals. Journal Citation Reports collects the citation data from the Web of Science Core Collection™, which includes journals indexed by the Science Citation Index Expanded™ and Social Sciences Citation Index™ (Clarivate 2021). We used the submission and publication dates of the corresponding papers to document the mean delay time from publication date to retraction date. Fifty percent of the results were randomly selected for double-checking by a second operator (NK) to increase the validity of the findings before statistical analyses were conducted. The Fisher’s exact test was used to examine the associations between different reasons for retractions and the retracted papers. To assess correlations, the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated. P < 0.05 was deemed to represent the statistically significant differences. We used the GraphPad Prism 8 for statistics.

Results

The number of Iran-affiliated retracted papers has been rising since 2012. We report that of 229 Iran-affiliated researchers identified as HCRs, 23 (10%) collectively had 51 retracted papers during 2006–2019. The 23 HCRs had published at least one paper which was retracted. The retracted papers included two reviews and 49 original papers. One of the researchers had 22 papers (43.1% of all the retracted papers by Iran-affiliated HCRs) retracted; however, 14 of the 23 (60.8%) HCRs authored only one paper which was retracted. Of the 23 HCRs, only two (8%) were women. Of the two women, one had co-authored two articles that were later retracted due to the authors’ requests. The third paper was retracted due to similarities with a previously published article. We found that 708 papers authored by all Iran-affiliated researchers were retracted from 2006 to 2019. Therefore, HCRs’ contribution to the total number of publications in that period was 7.2%. The shortest and longest times from publication to retraction dates were 20 and 2610 (mean ± SD, 857 ± 616) days, respectively. No association was found between the duration of time from publication to retraction dates and the dates of retractions. None of the retracted papers was written by a single author. Eleven, 13, 12, and eight papers were written by two, three, four, and five co-authors, respectively. Six-author, seven-author, and eight-author papers were two each, and only one paper was written by nine co-authors. The number of co-authors showed a strong negative correlation (r = − 0.9) with the number of retracted papers, and papers with two, three, four, and five co-authors constituted most of the retracted papers. An author’s position among the co-authors of a retracted paper did not show any significant association. Eight (16.8%) retracted papers had co-authors affiliated with international institutions. Only one paper had two international co-author affiliations (Pakistan and Saudi Arabia). South Korean collaborations were evident in two retracted papers, whereas Canada, Italy, and Japan constituted the rest of the international co-authorships of the retracted papers. We found that 36 retracted papers belonged to physics, chemistry, or physical chemistry; four papers related to nanotechnology and pharmaceuticals; three belonged to mathematical sciences; three were relevant to environmental sciences and renewable energy or industrial engineering; and five discussed toxicology, clinical medicine, or neuroscience and neurochemistry. Of all the journals which published the 51 papers, six (11.7%) did not have a documented impact factor. The highest impact factor was 10.5 for a journal that had published a review paper; the mean impact factor was 2.75. Eighteen papers were published in a journal with an impact factor of < 2, 17 papers with impact factor of 2 to < 4, 14 papers with 4 to < 6, and only two papers with > 6. Twenty-four retracted papers (47%) were published in journals with impact factor of < 2.73. Sixty-eight percent of the retracted papers were published in journals with an impact factor of < 4 (P < 0.05). One researcher had 22 papers retracted, three researchers had five papers, and two had four retracted papers. We did not find any significant relationship between the authorship ranking or contribution with the number of retracted papers.

Reasons for Retractions of the HCR Papers

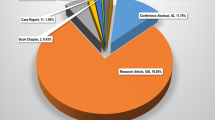

Of the 51 papers, 43 (84%) had a single reason for retraction, whereas eight had multiple reasons. Twelve of 16 papers published in journals with an impact factor of ≥ 4 were retracted due to fake peer-review (P > 0.05). Fourteen (27.4%) papers were retracted due to duplication of either an image, table, or text. Among the papers retracted due to a single reason, 23 (53%) were due to fake peer-review, eight (18.6%) had duplication, six (13.9%) due to errors, four (9.3%) had plagiarism, and two (4.6%) with a “Notice, Limited or No Information”. Of the retractions due to multiple reasons, five (62.5%) were duplication of an image or text and one fake peer-review. More than two-thirds of the papers were retracted because of duplication and fake peer-review (Fig. 1). Two (3.9%) papers were retracted due to journal or publisher errors, and none of these was retracted by an author’s request.

Discussion

We report the main causes of the retractions of the papers published by the Iran-affiliated HCRs. Because the Iranian HCRs attract high numbers of citations yearly, they are the source of aspiration for many early-career researchers. Expectedly, HCRs should set examples of ethical conduct of research at highest standards. We report that 27% of the retracted papers written by Iran-affiliated HCRs had duplication of text, a figure, or a table, as investigated from 2006 to 2019. This is a regrettable percentage, and urgent counteraction is needed to bar this easily preventable misconduct. Moreover, none of the papers with duplication were retracted by the authors’ requests. Acting ethically and responsibly, the authors could have informed the respective journals about their errors. Lack of effective education on the ethics of scientific publishing and authorship responsibility may have led to such retractions.

The recent rise in the number of retraction notices may be attributed to two reasons. (1) Since 2005, software programs to detect duplication or plagiarism have become available and used widely (Martin 2005). For example, in the last 10 years, the number of retracted papers with duplication has slightly increased, regardless of their authorship by HCRs. (2) The journal editors are presently more aware of, and have implemented measures to prevent, fake peer-review. Fake peer-review is a global problem for every publisher although many may decline reporting them, fearing damage to their reputation. Retractions because of fake peer-review can be easily prevented. A well-versed journal editor or a competent handling editor should be capable of finding and recruiting sufficient suitable, external reviewers to facilitate the peer-review of a manuscript. Duplication and plagiarism were reported previously, each constituting approximately 26% of the notices of retractions; however, we found them to constitute 27% and 9%, respectively (Steen 2011). Similarly, Fang et al. (2012) reported 14% for the duplication and 9.8% for plagiarism. However, the two previously described studies (Fang et al. 2012; Steen 2011) did not specifically involve retractions attributed to HCRs.

Implications of Our Report for RWD Operation

We report that only two (3.9%) of the HCR papers were retracted due mainly to technical errors by a journal or a publisher. For example, the paper with DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2005.04.013 was retracted by the journal, mentioning that “The Publisher regrets that this article is an accidental duplication of an article that has already been published in SAA [Spectrochimica Acta Part A], Volume 63, Issue 1, 1–252 [9–14]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2005.02.049. The duplicate article has therefore been withdrawn.” RWD however attributed “duplication” for this retraction. This attribution is incorrect—“accidental duplication by the publisher” or “error by the publisher or journal” should have been listed as the reason for retraction. In a second similar case, the paper with DOI https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-gtd.2016.1956 was retracted because an incorrect file version was uploaded, and the journal declared that “This article has been withdrawn as the incorrect text was uploaded due to a technical error.” Undoubtedly, no journal or publisher must commit such unfortunate errors, and more importantly, such errors must not be attributed to the authors. Given these findings, we suggest that RWD revise their procedures, so that reasons for retractions are listed and attributed correctly. We would like to highlight that some journals rarely or never issue notices of retractions while we understand that errors do happen; thus, heightened public awareness can indirectly affect such journals.

During conduction of this study, we did not have access to WoS; thus, we could not retrieve names and affiliations of the HCRs of other countries to perform a suitable comparison. Besides, the low number of HCRs with retractions hampered a robust statistical analysis.

Implications for the Iranian Academia

Presently, no regulation or transparent procedures exist to deal with authors with retracted papers, regardless of their HCR status. We hope that our report will trigger discussions on establishing policies and procedures to recognize and counteract unethical and questionable research practices and authorship misconduct. Establishing an overarching national body is necessary to revise, change, and constantly review the research practices and ethics in Iran. The relatively high rates of duplications and fake peer-reviews as the most common reasons for retractions reflect serious malpractices and misconducts. We suggest that establishing and wide promotion of improved and effective educational programs on publishing ethics (Elsevier 2021; Wiley 2021) will reduce the alarming rate of paper retractions.

Of the 23 HCRs, two were women with three retracted papers. This finding highlights that some Iranian women had achieved the HCR status (despite retracted papers), reflecting their academic empowerment. However, we cannot conclude that this could potentially reflect gender inequity in Iranian academia. Previous opinions and debates have discussed the roles of Iranian women in education and academia (Janghorban et al. 2014; Rahbari 2016; Winn 2016). We do not intend to discuss this further because studying women’s empowerment in Iran requires further research and is beyond the scope of this manuscript.

High numbers of retractions arguably indicate that authors and journal editors proactively identify and remove fraudulent or erroneous papers (Fanelli 2013). Such positive dispositions should be supported because identifying the causes of retractions fosters scientific integrity. Iran has a high rate of publications per year; thus, Iranian academic institutions should support widespread, targeted training programs and resources such as iThenticate (Kalnins et al. 2015; Supak-Smolcic and Simundic 2013). While retractions are seen as a stigma by the Iranian academics, promoting awareness about importance of the proactivity about retractions and their avoidance should become an academic aspiration. Ministry of Science, Research and Technology and Ministry of Health and Medical Education as two stakeholders of Iranian basic science and clinical research should establish policies and training programs about retractions.

Implications for the Role of the Clarivate Analytics

Nominating HCRs should follow additional and strict selection criteria besides the present standards, which mainly reflect the number of attracted citations. A Korean–U.S. HCR was banned from joining the editorial board of the Journal of Theoretical Biology because of soliciting citations to their papers (Van Noorden 2020). Such practices highlight that publishing ethics are not upheld even in some of the developed countries (Van Noorden 2020). Because we found that almost one-tenth of the Iran-affiliated HCRs had retracted papers, we advise that unethical conduct by any researcher must be considered before nominating them as an HCR. Undertaking fake peer-review, manipulating any peer-review, or duplications are sufficient reasons to rescind a researcher’s HCR status. Soliciting citations to one’s work is another malpractice that should revoke the HCR status.

References

Alberts, B., Cicerone, R. J., Fienberg, S. E., Kamb, A., McNutt, M., Nerem, R. M., et al. (2015). SCIENTIFIC INTEGRITY. Self-correction in science at work. Science, 348(6242), 1420–1422. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab3847.

Al-Hidabi, M. D. A., & Teh, P. L. (2019). Multiple publications: The main reason for the retraction of papers in computer science. In K. Arai, S. Kapoor & R. Bhatia (Eds.), Advances in information and communication networks, Cham (pp. 511–526). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03402-3_35.

Ataie-Ashtiani, B. (2017). Chinese and Iranian scientific publications: Fast growth and poor ethics. Science and Engineering Ethics, 23(1), 317–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9766-1.

Brainard, J., & You, J. (2018). What a massive database of retracted papers reveals about science publishing’s ‘death penalty’. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/10/what-massive-database-retracted-papers-reveals-about-science-publishing-s-death-penalty

Budd, J. M., Coble, Z., & Abritis, A. (2016). An investigation of retracted articles in the biomedical literature. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 53(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2016.14505301055

Budd, J. M., Sievert, M., & Schultz, T. R. (1998). Phenomena of retraction: Reasons for retraction and citations to the publications. JAMA, 280(3), 296–297. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.3.296.

Callaway, E. (2016). Publisher pulls 58 articles by Iranian scientists over authorship manipulation. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from https://www.nature.com/news/publisher-pulls-58-articles-by-iranian-scientists-over-authorship-manipulation-1.20916

Clarivate Analytics. (2019). Global highly cited researchers 2019 list reveals top talent in the sciences and social sciences. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-highly-cited-researchers-2019-list-reveals-top-talent-in-the-sciences-and-social-sciences-300960223.html.

Clarivate. (2021). Journal impact factor journal citation reports-web of science group. Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/journal-citation-reports/.

Docampo, D. (2010). On using the Shanghai ranking to assess the research performance of university systems. Scientometrics, 86(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0280-y.

Elsevier. (2021). Publishing ethics for editors. Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://www.elsevier.com/about/policies/publishing-ethics.

Fanelli, D. (2013). Why growing retractions are (mostly) a good sign. PLoS Medicine, 10(12), e1001563. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001563.

Fang, F. C., Steen, R. G., & Casadevall, A. (2012). Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(42), 17028–17033. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212247109.

Gasparyan, A. Y., Nurmashev, B., Seksenbayev, B., Trukhachev, V. I., Kostyukova, E. I., & Kitas, G. D. (2017). Plagiarism in the context of education and evolving detection strategies. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 32(8), 1220–1227. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.8.1220.

Goodall, A. H. (2009). Highly cited leaders and the performance of research universities. Research Policy, 38(7), 1079–1092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.04.002.

ISNA News Agency. (2019). Iran ranks 15th in Web of Science in terms of number of articles. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://en.isna.ir/news/98091107445/Iran-ranks-15th-in-Web-of-Science-in-terms-of-number-of-articles.

Jamieson, K. H. (2018). Crisis or self-correction: Rethinking media narratives about the well-being of science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(11), 2620–2627. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708276114.

Janghorban, R., Taghipour, A., Latifnejad Roudsari, R., & Abbasi, M. (2014). Women’s empowerment in Iran: A review based on the related legislations. Global Journal of Health Science, 6(4), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v6n4p226.

Kalnins, A. U., Halm, K., & Castillo, M. (2015). Screening for self-plagiarism in a subspecialty-versus-general imaging journal using iThenticate. AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 36(6), 1034–1038. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4234.

Kolahi, J., & Abrishami, M. (2013). Contemporary remarkable scientific growth in Iran: House of Wisdom will rise again. Dental Hypotheses, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.4103/2155-8213.110177.

Martin, D. F. (2005). Plagiarism and technology: A tool for coping with plagiarism. Journal of Education for Business, 80(3), 149–152. https://doi.org/10.3200/joeb.80.3.149-152.

Oransky, I. (2018). Volunteer watchdogs pushed a small country up the rankings. Science, 362(6413), 395. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.362.6413.395.

Rahbari, L. (2016). Women in higher education and academia in Iran. Sociology and Anthropology, 4(11), 1003–1010. https://doi.org/10.13189/sa.2016.041107.

Rezaee-Zavareh, M. S., Naji, Z., & Salamati, P. (2016). Creating a culture of ethics in Iran. Science, 354(6310), 296. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal0019.

Steen, R. G. (2011). Retractions in the scientific literature: Is the incidence of research fraud increasing? Journal of Medical Ethics, 37(4), 249–253. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.040923.

Steen, R. G., Casadevall, A., & Fang, F. C. (2013). Why has the number of scientific retractions increased? PLoS One, 8(7), e68397. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068397.

Stone, R. (2016). In Iran, a shady market for papers flourishes. Science, 353(6305), 1197. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.353.6305.1197.

Stroebe, W., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2012). Scientific misconduct and the myth of self-correction in science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612460687.

Student News Network [Khabarguzari Daneshjoo]. (2020). The number of highly cited scientists of the University of Science and Techology of Iran reached seventeen—a five-fold increase compared to the past six years. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://snn.ir/fa/news/730803.

Supak-Smolcic, V., & Simundic, A. M. (2013). Biochemia Medica has started using the CrossCheck plagiarism detection software powered by iThenticate. Biochemia Medica (Zagreb), 23(2), 139–140. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2013.016.

Tabnak Professional News Site. (2020). Introduction of 228 superior scientists of Iran. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from http://www.tabnak.ir/fa/news/683166.

Van Noorden, R. (2020). Highly cited researcher banned from journal board for citation abuse. Nature, 578(7794), 200–201. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00335-7.

Wang, T., Xing, Q. R., Wang, H., & Chen, W. (2019). Retracted publications in the biomedical literature from open access journals. Science and Engineering Ethics, 25(3), 855–868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-018-0040-6.

Web of Science Group. (2020a). Highly cited researchers. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://recognition.webofsciencegroup.com/awards/highly-cited/2019/methodology/.

Web of Science Group (2020b). Highly cited researchers. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://publons.com/awards/highly-cited/2019/.

Wiley. (2021). Best practice guidelines on publishing ethics. Retrieved May 22, 2021, from https://authorservices.wiley.com/ethics-guidelines/index.html.

Wilson, B. (1997). CVI. A retractation, by Mr. Benjamin Wilson, F. R. S. of his former opinion, concerning the explication of the Leyden experiment. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 49, 682–683, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1755.0107

Winn, M. K. (2016). Women in higher education in Iran: How the Islamic revolution contributed to an increase in female enrollment. Global Tides, 10.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the comments and constructive suggestions by our peer-reviewers because they helped us enrich and improve our manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kamali, N., Rahimi, F. & Talebi Bezmin Abadi, A. Learning from Retracted Papers Authored by the Highly Cited Iran-affiliated Researchers: Revisiting Research Policies and a Key Message to Clarivate Analytics. Sci Eng Ethics 28, 18 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-022-00368-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-022-00368-3