Abstract

This paper explores the gray area of questionable research practices (QRPs) between responsible conduct of research and severe research misconduct in the form of fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism (Steneck in SEE 12(1): 53–57, 2006). Up until now, we have had very little knowledge of disciplinary similarities and differences in QRPs. The paper is the first systematic account of variances and similarities. It reports on the findings of a comprehensive study comprising 22 focus groups on practices and perceptions of QRPs across main areas of research. The paper supports the relevance of the idea of epistemic cultures (Knorr Cetina in: Epistemic cultures: how the sciences make knowledge, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1999), also when it comes to QRPs. It shows which QRPs researchers from different areas of research (humanities, social sciences, medical sciences, natural sciences, and technical sciences) report as the most severe and prevalent within their fields. Furthermore, it shows where in the research process these self-reported QRPs can be found. This is done by using a five-phase analytical model of the research process (idea generation, research design, data collection, data analysis, scientific publication and reporting). The paper shows that QRPs are closely connected to the distinct research practices within the different areas of research. Many QRPs can therefore only be found within one area of research, and QRPs that cut across main areas often cover relatively different practices. In a few cases, QRPs in one area are considered good research practice in another.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This paper explores the gray area of questionable research practices (QRPs) between responsible conduct of research (RCR) and severe research misconduct in the form of fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism (FFP) (Steneck, 2006). Up until now, we have had very little knowledge on similarities and differences in QRPs between main areas of research. In this article, we present the findings of a comprehensive study comprising 22 focus groups on disciplinary differences in practices and perceptions of QRPs. We explore whether researchers across disciplines and main areas of research agree on practices that may be considered as a violation of good research practices. In line with the well-established disruption of the ‘idea of the epistemic unity of the sciences’ (Knorr Cetina & Reichmann, 2015, 873), we find despite many similarities no one unified position when it comes to practices that are perceived as questionable or detrimental to the performance of sound and responsible research. Hence, our findings show variation within and across main areas of research (humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, technical sciences, and medical sciences) in the types of QRPs that researchers point to as being the most prevalent and severe within their disciplines. We further find that the QRPs reported often carry very different meanings within the different main areas of research, depending on how the research process is understood and approached.

After presenting the findings, we discuss to which extent the QRPs depict differences across different knowledge production models, i.e. whether they reflect key variation in epistemic cultures and the processes of doing science (Knorr Cetina, 1999; Knorr Cetina & Reichmann, 2015). While it can be argued that the norms and values of research as idealized precepts and part of normative systems help shed light on research behavior and enter into analysis of research misconduct (Anderson et al., 2010, 371), this article is primarily concerned with the practice of research. In this regard, the study is grounded in traditions that foreground ‘science as practice’ rather than ‘science as knowledge’ with the former addressing knowledge production processes rather than scientific products (Pickering, 1992). In line with previous approaches to studying such processes—e.g. ‘thought styles’ (Fleck, 1979; Penders et al. 2009), ‘epistemological styles’ (Lamont, 2009, 54), or ‘epistemic cultures’ (Knorr Cetina, 1999) we ascribe to the premise that “the sciences are in fact differentiated into cultures of knowledge that are characteristic of scientific fields or research areas” (Knorr Cetina & Reichmann, 2015, 873). Still, we agree that an epistemic focus on practice necessitates an analytical awareness on meaning as both defining for and created through practice. By exploring QRPs and perceptions, we are interested in both practice and discourse, i.e. in investigating “how practitioners distinguish signal from noise” (Knorr Cetina & Reichmann, 2015, 873–874). Our object of analysis is main areas of research represented by a number of various disciplines similar in knowledge production models (see sampling criteria in the methods section). It is a more aggregated level than in epistemic culture theory (Knorr Cetina & Reichmann, 2015, 876), but similar to this approach, the division of fields is premised on practice rather than on designation.

In the following sections, we first present the existing knowledge on QRPs before presenting the contribution of our paper. Hereafter, we give an account of the methods used and this section is followed by a results section with five subsections, one per main area of research (humanities, medical sciences, technical sciences, social sciences, and natural sciences). The paper ends with a discussion of the results.

Questionable Research Practices (QRPs)

QRPs can be described as a gray area between responsible conduct of research (RCR), on the one side, and severe research misconduct in the form of fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism (FFP), on the other (cf. Steneck, 2006). The term questionable research practice was first used in the American Association for Public Opinion Research’s Code of Professional Ethics and Practices from 1958 (Banks et al., 2016). Yet, the breakthrough of the concept came with the National Academy of Science’s report Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process published in 1992 (National Academy of Science, 1992).

Compared to FFPs, QRPs appear more difficult to conceptualize, and QRP definitions often employ a rather broad characterization in order to encompass a wide-ranging collection of different and potentially detrimental practices. In the influential National Academy of Science report from 1992, QRPs are defined as “actions that violate traditional values of the research enterprise and that may be detrimental to the research process” (National Academy of Science, 1992, 5–6). Banks et al. (2016) also emphasize the broadness of the many definitions available and summarize recent QRP definitions as “design, analytic, or reporting practices that have been questioned because of the potential for the practice to be employed with the purpose of presenting biased evidence in favour of an assertion” (Bank et al., 2016, 7). According to Bouter et al. (2016), QRPs involve a great number of diverse actions related to both the study design, the data collection process, the reporting phase and to research collaborations, including such topics as authorship distribution, reviewing, and supervision (Bouter et al., 2016, additional file 3).

Many of the studies of QRPs (and research misbehavior, in general) conducted since the release of the National Academy of Science report have attempted to measure the extent of detrimental research practices in science (e.g. Dal-Réet et al., 2020; Fanelli, 2009; Godecharle et al., 2018; Hofmann & Holm, 2019; Martinson et al., 2005). These studies generally find that the majority of researchers conduct research in a responsible way, and that only a minority engage in serious forms of research misconduct (FFP). Simultaneously, these studies show that numerous researchers from time to time have been engaged in integrity-breaching practices that fall between RCR and FFP in the gray area of QRPs. It has proven difficult to measure the exact extent of the application of QRPs and the number of researchers who have been involved in FFP and QRPs. According to Fanelli’s meta-analysis of surveys on misconduct, however, around 2% of scientists admit to having been involved in FFP practices, and up to a third of all scientists self-confess to having been involved in some forms of QRPs (Fanelli, 2009, 8). The demarcation between QRP and FFP practices is not clear, and a number of scholars have emphasized that some QRPs may even be more detrimental to the integrity of research than FFPs, among others due to their greater prevalence (Anderson et al., 2013; Fanelli, 2009; John et al., 2012; Steneck, 2006; Bouter et al., 2016; Bouter, 2020). The National Academy of science points to a number of practices earlier labelled as QRPs—such as ‘detrimental authorship practices’ or’misleading statistical analysis’—‘as not questionable at all but as clear violations of the fundamental tenets of research’. (National Academy of Science, 2017, 73). To underline the damaging effects of QRPs, the National Academy of Science therefore advised scientists to label QRPs ‘detrimental research practices’ due to the fact that they may very well be harmful and not only questionable (2017, 61; Shaw, 2019, 1089). In the revised European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, practices that fall outside of the FFP definition are labelled as ‘unacceptable practices’ (ALLEA, 2017). Despite variation and changes in nomenclature, we apply the concept of questionable research practices (QRPs), as it remains the most commonly used term internationally (Bouter, 2020). Furthermore, the term is applied in Danish legislation. Therefore, we use the concept of QRPs in the following. Nevertheless, while QRPs are defined as “actions that violate traditional values of the research enterprise” (National Academy of Science, 1992, 5–6), they cannot be regarded as equally detrimental or harmful across all disciplines and research fields, as we shall see in the following.

Knowledge Gaps and This Study’s Contribution

As mentioned, a small but growing body of work addresses and tries to document the scale of research misconduct and QRPs as well as their causes and effects (e.g. Banks et al., 2016; Butler et al., 2017; Fanelli, 2009; Hall & Martin, 2019; John et al., 2012; Bouter et al., 2016; Haven et al., 2019; National Academies of Science, 2017; Steneck, 2006; Tijdink et al., 2014). However, despite the fact that research integrity has become an established research field, not least thanks to targeted EC granting programs (Bouter, 2020; Davies, 2019), most work on detrimental research practices has so far only been performed within the biomedical and behavioral sciences. We therefore know very little about, for instance, how the 60 QRPs that materialized from Bouter et al. study (2016, additional file 3) are understood within and across different main areas of research. We also have limited knowledge on whether such practices are equally prevalent within all disciplines and if they are regarded as equally severe across the main areas of research. When Bouter et al. (2016), for example, finds that to “selectively cite to enhance your own findings or convictions” is the most frequently found QRP, we do not know whether ‘selective citing’ carries on the same meaning for all fields of research, and whether this practice is equally prevalent among all fields. The same objection could be made for other QRPs listed in this and similar studies. Nonetheless, some of the QRPs recorded in Bouter et al. (2016) clearly pertain to distinct knowledge production models. When the study, for instance, finds that to “not publish a valid ‘negative’ study” is the third most frequent QRP, disciplines that employ a hypothesis-testing approach are employed as a general mode of knowledge production. This QRP would, in other words, not take third place within the humanities, for instance.

Knowledge on disciplinary differences is key for policy makers, research institutions and disciplines in opposing detrimental research practices. There is no one-size-fits-all and insight from one area of research cannot simply be transferred to other areas. However, despite growing awareness and recognition of disciplinary differences in the perception and practices of QRPs (e.g. Horbach & Halffman, 2019; Haven et al., 2019; Davies, 2019, 1242), we still have limited knowledge on how the main areas of research relate to different QRPs. It is this knowledge gap that has motivated our study. We wanted to gain in-depth knowledge on the perceptions and practices of QRPs across main areas of research.Footnote 1 For this purpose, we conducted 22 focus group interviews across all main areas of research. Based on these interviews, the paper is able to give a first, systematic insight into similarities and differences in QRPs and understandings hereof across main areas of research.

Methods

This article seeks to answer the following three research questions:

-

1.

Which practices do researchers from the different main fields of research (humanities, social sciences, medical sciences, natural sciences, and technical sciences) identify as QRPs, and in what way do these QRP practices relate to different phases in the research process?

-

2.

How do researchers from different research areas define and assess these QRPs?

-

3.

To which extent do the QRPs relate to variation in research practices and ‘epistemic cultures’?

In order to answer these questions, we conducted 22 focus group interviews at eight universities in Denmark. The focus groups were composed in view of homogeneity in research practices and included researchers from either the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, technical sciences or medical sciences, representing sub-disciplines with a similar orientation in research.

This meant that the five humanities groups were formed based on the researchers’ main orientation in research: We conducted one focus group interview with researchers from language disciplines, one with researchers from philosophical disciplines, one with researchers from historical disciplines, one centered on the aesthetic disciplines, and one with scholars from the communication disciplines.Footnote 2 In the social sciences, we conducted four interviews. Here, the focus groups were formed on the basis of whether the interviewees had a qualitative (two groups) or a quantitative (two groups) orientation in their research. In the natural sciences, we formed laboratory/experimental groups (two groups) and theoretical groups (two groups), respectively, and in the medical sciences, groups were composed as either basic research groups (two groups) or clinical/translational groups (two groups). We also conducted four focus group interviews within the technical sciences. Here, we did not use any subdivision. Finally, we conducted one interdisciplinary interview at the IT University of Denmark. Findings from this group are not included, since we focus on disciplinary differences here. Table 1 shows which disciplines were represented in the focus group interviews.

Heterogeneity was introduced through variation in career levels, gender and institutional affiliation (for details on research design, including participant distribution and sample-, recruitment- and coding strategy, please see Appendix 1).

Each focus group had three to six participants, and a total of 105 researchers took part in the study (see Table 2 for details on gender and academic level).

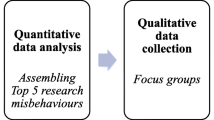

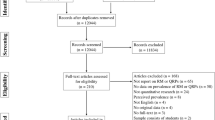

The interview design included a ranking exercise to gain an understanding of how different disciplinary research fields assess the prevalence and severity of different QRPs. As a first part of the exercise, participants were asked to write down a severe or prevalent QRP within their area of research. In this article, we address the 34 different QRPs that came out of this part of the exercise (see Appendix 2 for a list of the 34 QRPs). These 34 QRPs were derived through an extensive coding and validation procedure of the 107 QRPs that the interviewees themselves reported (see Appendix 1, and for a complete list of reported QRPs, see Supplementary Material in the folder “Focus Group Study” at the PRINT project’s OSF site: https://osf.io/rf4bn/).

In order to increase our understanding of the observed similarities and differences between disciplinary fields of research, we categorized each of the reported QRPs according to different phases in the research process. Naturally, such processes depend on the research in question and particular knowledge production models, and no one model exists. As an analytical construct, though, the five categories applied do fit with more generic ways of approaching different phases of the research process (e.g. Schwartz-Shea & Yanow, 2012; Bouter et al., 2016, additional file 3; Moher et al., 2020). They also broadly cover the reported QRPs found in this study in terms of whether they, for instance, relate to collecting, analyzing, or reporting data. The division applied includes five stages: idea generation, research design, data collection, data analysis, and scientific publication and reporting.

In the analysis, we include a within and an across case analysis. The former details in-depth explorations of the emerging QRPs (cf. Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) within each field of research to understand their distinctiveness in terms of field disciplinary perceptions and assessments. The across case comparison adds to this analysis by identifying and discussing differences and similarities across the main field of research in relation to epistemic differences.

Results

In this section, we present the QRPs that interviewees reported as being prevalent, severe, or simply creating a lot of ‘noise’, at large, within their fields of research. We analyze how the different fields of research perceive and assess these practices in relation to the five analytical phases of the research process presented above: idea generation, research design, data collection, data analysis, and scientific publication and reporting. We begin with the humanities.

Humanities: Unoriginality and Plagiarism-Like Behavior

As a general field of research, the academic literature on research integrity and detrimental research practices remains particularly limited when it comes to the humanities. Accordingly, we know very little about detrimental research practices within the humanities in comparison with other main areas of research such as the biomedical or social sciences, where especially psychology and behavioral science have been subject to several studies (Haven et al., 2019; John et al., 2012; Steneck, 2006). In our study, we have tried to shed light on QRPs within the humanities by conducting five focus group interviews with representatives from five different disciplinary areas within the humanities: language disciplines, philosophical disciplines, historical disciplines, aesthetic disciplines, and communication disciplines.

Idea Generation

For the humanities, unoriginality is seen as a very widespread QRP. As a dictionary denotation, unoriginality is described as a quality rather than an actual practice. Nonetheless, in the focus group interviews, unoriginality is perceived as a detrimental practice that intersects with the production of research. It is not regarded as particularly severe for individual research careers or for research as a whole, but it creates a lot of ‘noise’, and it is together with the other QRPs considered a symptom of a research system characterized by publication pressure and hyper-competition. Unoriginal work is seen as “boring”, “uninteresting”, a waste of time, and as research that “doesn’t add anything new”. Moreover, the (mass) production of unoriginal work showcases both a “lack of curiosity” and an “avoidance of risk taking”. Instead, according to the interviewees, research should be “inspiring for practice and thought provoking”, and knowledge should provide new perspectives on the world and new understandings of phenomena such as a piece of art, a classic novel, a historical event etc. The concern about unoriginality is closely related to the QRP plagiarism-like behavior, for lack of a better name, though it is perceived as more severe. Examples of plagiarism-like behavior in our study include design structure, content adapted from another research area, and running with other researchers’ ideas both with and without quoting them (QRP 24, see Supplementary Material (SM) in the folder “Focus Group Study” at the PRINT project’s OSF site: https://osf.io/rf4bn/). In cases where others’ work is cited, plagiarism-like behavior resembles the practice, which Shaw (2016) calls ‘the Trojan citation’. Here, the work of others is cited superficially, while at the same time the basic ideas are plagiarized.

It is not plagiarism as such, but nor is it quite … It is definitely taking it to the limit. You may take ownership of some ideas that are not quite your own. (Associate professor, history of ideas, focus group 1, p. 26)

The same researcher points to original ideas as ‘what you have’ in the humanities, a kind of intellectual capital, and therefore something you guard with care. Contrary to the emphasis given within the humanities, the plagiarism-like behavior is only mentioned once as a QRP within the other main areas of research. A researcher from the technical sciences refers to an example of translating others’ valuable research results into your own frame (see below).

Research Design

In relation to research design, researchers within the humanities point to insufficient preparation and reading (QRP 13, SM) and exclusion of other traditions (QRP 4, SM) as examples of QRPs. The latter refers to competing research traditions omitted from research based on questionable grounds. This QRP is both perceived as rather prevalent and rather severe, whereas inadequate knowledge about existing research is seen as less severe, though equally common.

Data Collection

Breach of ethical principles refers to questionable treatment of human subjects. In the examples given, this behavior specifically refers to hidden recordings of participants, crossing ethical boundaries in interview questions, and providing participants with wrong information that is not corrected afterwards (QRP 1, SM). The practice of cherry-picking sources and data is also brought forward by a researcher within the historical disciplines:

You start with the hypothesis and then pick the data that match it. And if you encounter something along the way that falsifies it, then you just reuse it in a slightly altered form so that it matches the available data. (Associate professor, history, focus group 10, p. 15)

The practice of inadequate data management and data storage (QRP 9, SM) confounds researchers across disciplinary fields, not least in terms of the implications of the new EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that was to be implemented shortly after the completion of the focus group interviews. Considerations primarily concern the availability of appropriate systems for storing data and proper mechanisms for sharing data. As an emerging QRP, however, only researchers from the discipline of communication consider managing and storing data a potential QRP (QRP 9, SM):

(…) I think it is definitely challenging. There are new types of data, that is, specifically digital data, you know. These new digital platforms contain information, because it is a constant question: “Is this private property? Is it public data? Can I use it without asking you?” So I mean, it’s incredibly difficult. (Associate professor, communication, focus group 14, p. 15)

As stated in the quotation, researchers working with, for instance, social media data from various digital platforms find it challenging to identify precise guidelines for conducting virtual ethnography in relation to consent, data status, and data storage.

Data Analysis

In addition to p-hacking, mentioned as a QRP by researchers from the discipline of sociolinguistics (see above), researchers from the disciplines of aesthetics and history consider lack of validation a QRP, which concerns research conclusions that are not or only weakly grounded in empirical data (QRP 19, SM). This relates to the QRP of theoretical and methodological authority arguments, where fashionable theories like those of Gilles Deleuze, for example, are applied uncritically, for instance as a bedrock for methodical choices. An associate professor in journalism also points to the QRP of inadequate use of methods in interpreting and reporting qualitative research in a quantified fashion (QRP 31, SM).

Scientific Publication and Reporting

Researchers from the disciplines of history and communication problematize the re-use of research material. It is not to be understood as self-plagiarism or salami slicing, but rather as using the same results in different outlets and formats, for instance in a re-written or translated form (QRP 26, SM). As within the medical and social sciences, selective citing is stated as a QRP and implies research outputs that insufficiently refer to other research (incomplete reference lists). A researcher from the language discipline problematizes the practice of overgeneralizing results (QRP 21, SM):

(…) which leads a lot in our field to essentialising, where you end up saying, “Teenage Latinas sound like this,” and that’s like not at all what you want to say. (Assistant professor, sociolinguistics, focus group 7, p. 10)

For the humanities, it is evident that the nature of research is not only philosophical, literary, or conceptual, but that preferred research approaches and knowledge production models also cover qualitative and quantitative empirical methods for data collection and data analysis. This diversity is represented in the QRPs that emerged during the focus group exercise. Compared to other fields of research, the concern about continuously being able to retain original ideas and produce original research comes across as particularly manifest.

Medical Sciences: Inadequate Use of Methods and Lack of Validation

In this study the medical sciences were represented by researchers doing either basic research (two groups) or clinical/translational research (two groups), see Table 1. While qualitative studies and hypothesis-generating research are mentioned as potential research approaches, prevalent among the researchers representing the (bio) medical research field are hypothesis-testing modes of performing research as well as quantitative and significance-testing forms of knowledge production. This approach to knowledge production permeates the QRPs brought forward in the interviews. Across the different phases of our analytical research process model, lack of credible and valid research results due to inadequate methods, selection of data, and HARKing, for instance appears as a cross-cutting theme in the discussions on QRPs. The medical researchers do not point to any QRPs pertaining to the idea generation phase, and we therefore start by looking at research design.

Research Design

When designing a (bio)medical study, researchers from clinical research throw into question the inadequate use of methods (QRP 11, SM). Among the examples mentioned are applying incorrect statistical methods, refraining from using blind studies when they would have been appropriate, and reproducing a qualitative study in a mixed methods research setup. Lack of a clear research question (QRP 14, SM) is also identified as a QRP:

People actually set up some very large studies; they may also be expensive and involve a lot of people, but they have not prepared a clearly defined research question in advance. (Associate professor, forensic medicine, focus group 13, p. 16)

Lack of a clear and well-defined research question is considered both prevalent and severe in cases where a non-significant study ends up being a ‘fishing trip’ and is changed into a descriptive one due to the poorly constructed research question. Some studies may function as hypothesis-generating, but the objective should be stated up front, according to the discussion in one of the clinical focus groups.

Data Collection

In a similar vein, fishing data, i.e. looking at data without a plan, is perceived as a severe QRP (see above). Like the other research areas, cherry-picking sources and data is also identified within the medical sciences as a QRP. A professor in biomedicine describes this QRP as selecting data which fits with one’s hypothesis:

I wrote selection of data. So that means that you have some hypothesis and then runs 10 experiments. And two of them fit your hypothesis and then you pick them and then you’ve proven your hypothesis (…). It is a problem, this thing with formulating a hypothesis that you love and then set up experiments to prove it instead of falsify it, which you would call good practice. And it appears in the jargon, you hear it time and time again, that people want to demonstrate that something is a specific way instead of examining what it is like. (Associate professor, biomedicine, focus group 26,Footnote 3 pp. 14–15)

This QRP is described as both prevalent and rather severe.

Data Analysis

The practice of deviating from one’s original design thematically cuts across the QRPs identified by medical researchers. Inadequate use of data (QRP 10, SM), i.e. retention of data and use of data beyond the specific objective for which it is collected, is also stated as a QRP, as is HARKing. Examples of HARKing both as presenting a post hoc hypothesis as though it was an a priori hypothesis and as omitting a hypothesis after completing the analysis (QRP 7, SM) were discussed in the interviews. P-hacking was pointed out by both the basic and clinical research focus groups:

If you analyze data long enough, if you torture data long enough, they will ultimately confess, right? So in the end, you find an appropriate filtering and an appropriate method so that something significant comes out of it, and that just is not the right way to do it (…). P-hacking, that is precisely it. And I actually see that as the biggest genuine challenge in my field today, that p-hacking is really widespread, and in reality I don’t think that most do it neither deliberately nor of ill will, but they simply don’t realize that that’s what they are actually doing. (Associate professor, biomedicine, focus group 23, pp. 6–7)

Furthermore, exclusion of other traditions in the sense of excluding alternative interpretations based on a “dogmatic mind-set” (QRP 4, SM) or lack of critical reflection, i.e. refraining from considering underlying relations and explanations (QRP 4, SM), relate to the topic of lack of validation of research results (QRP 19, SM) through proper controls, for instance in connection with vaccine placebo studies, reagents, and animal models. Lack of validation is also discussed and problematized as a lack of reproducibility. The “reproducibility crisis”, understood as the difficulties of independent researchers in reproducing study findings (Resnik & Shamoo, 2017), was a topic of awareness and varying concern across both the medical, social, natural, and technical sciences.

Scientific Publication and Reporting

As within the social and natural sciences, unfair assignment of authorship is brought up as a QRP among the medical researchers. It encompasses, like many of the other QRP examples, a broad range of ways to misbehave. In this particular instance, an associate professor in biomedicine provides an example of someone submitting an abstract with named co-authors without first showing the abstract to the named co-authors (QRP 33, SM). Selective citing (QRP 28, SM), i.e. excluding ‘unfit’ references from a review, selective reporting of research findings, i.e. omitting relevant and alternative explanations (QRP 28, SM), and lack of transparency in the use of methods and empirical data when describing the particular research approach (QRP 18, SM) are all QRPs that speak to issues of non-disclosed selection of data etc., which challenges research quality assessment and replicability.

Technical Sciences: Lack of Validation and Cherry-Picking Data

As previously mentioned, the technical sciences were not divided into subareas based on research approach prior to recruitment. The four technical focus groups do however include researchers who represent a number of various disciplines such as energy- and food science, nanotechnology, photonics, and electrical engineering, among others (see Table 1). The theme of insufficient validation of research results cuts across many of the practices identified as QRPs in connection with the analysis and reporting of research findings. Cherry-picking data in the sense of excluding outliers in a non-transparent fashion is also a distinct QRP. Similar to the field of medical research, no participants from the technical sciences mentioned QRPs that relate to the idea generation phase, and we therefore start with research design here.

Research Design

When designing a study, inadequate use of methods (QRP 11, SM) is mentioned as problematic and refers in this case to blind use of standard protocols and insufficiently consideration of applicable methods. The latter could also figure in the analytical phase of a research process, as it also refers to the issue of generalizing in alignment with the explanatory force of different methods. Akin to the humanities, the QRP of insufficient preparation and reading (QRP 13, SM) is presented as a practice that is both prevalent and rather severe. As a professor in production engineering expresses, “It is critical because the entire scientific work may rest on a faulty basis if your state-of-the-art is poor” (focus group 8, p. 27). Another QRP, which aside from here is only mentioned in the humanities focus groups, is plagiarism-like behavior (QRP 24, SM), which is translating other scientists’ respected research results into one’s own frame (see above).

Data Collection

The QRP of non-representative sampling (QRP 20, SM) is described as the practice of conducting consumer surveys where the distribution of consumers is not well-defined. The use of non-representative samples is seen as very severe and rather widespread too.

Data Analysis

In the technical sciences groups, several researchers point to cherry-picking of data and lack of validation of research results as important QRPs within their field of research. Cherry-picking sources and data (QRP 2, SM) concerns unfounded removal of outliers.

It is this thing about failing to report experiments that figure as outliers. If they otherwise have a fine trend (…). I actually have a few examples where you misinterpret a trend, that is, where we get those outliers and realize it and then someone actually pushes the result. That is one of my pet peeves. (Associate professor, chemical engineering, focus group 8, pp. 10–11)

The questionable practice of failing to perform sufficient validation of the research results (lack of validation, QRP 19, SM) is evident from three different examples. The first example relates to the failure of continuing to test and challenge research conclusions. This practice is perceived as only somewhat severe but rather prevalent:

That if you get something spectacular. Then it’s smarter to publish it than go ahead and test how spectacular it is (…). You could choose to say: “Okay, now the project is completed,” or you could choose to say: “The project continues, and we test our findings thoroughly.” (Assistant professor, energy, focus group 17, pp. 16–17)

The second example is also considered rather prevalent, but only somewhat severe. It specifically targets the use of a new laboratory for each new measurement in an amplification process. This creates the low values desired by the research group that makes use of this practice, while making it difficult for other groups using just one laboratory to reproduce these values. By contrast, the third example is considered very severe and still prevalent, and it involves co-authoring of an article without performing a sufficient quality control of the data and methods that are used.

Ignoring negative results (QRP 8, SM) also relates to failure to properly validate research results. This QRP has to do with the questionable interpretation of mixed results; i.e. is an assay not working, or is it showing a negative result? In cases of doubt, negative results should not be disregarded too fast. If they are, it is considered both a rather severe and prevalent QRP.

Scientific Publication and Reporting

In relation to the publication of research findings, a researcher points to the QRP of unfair assignment of authorship (QRP 33, SM). In this case, the practice of by default including the recipient of a grant as co-author of all articles produced within the given project is questioned and considered partly unfair:

Well, I think in a way … they have spent a lot of time applying for grants and projects and stuff like that, and then they also need to be able to apply … to be able to qualify to apply for other projects, they also need this big H index, so in that way I don’t really think it’s unfair, because the system encourages it. Then again, you could say that in a way it is unfair because they didn’t do the work. (Assistant professor, production engineering, focus group 8, p. 10)

Selective reporting of research findings (QRP 29, SM) refers to the practice of abstaining from publishing negative results or withholding negative results that go against the utility of a specific technology. It is considered to be both prevalent and severe, as it may very well influence current and future research projects and industrial investments. The remaining identified QRPs relating to publication concern the validity of results. Sloppy use of figures in publications (QRP 30, SM) is one example, where researchers include graphs that have not been thought through and thus reveal a job not properly done.

The QRP of overselling methods, data, or results (QRP 22, SM) is mentioned in two different technical focus groups and refers to conclusions not being properly supported by data and results that are inflated through ways of writing.

Social Sciences: Cherry-Picking Data and Employing a Marketable Approach to Research

The social sciences focus groups are composed of researchers with either a qualitative (two groups) or a quantitative (two groups) orientation (see Table 1 for specific disciplines). Half of the self-reported QRPs that emerged in the focus groups were presented as important to both qualitative and quantitative researchers. Cherry-picking data, an instrumental and marketable approach to research, unfair assignment of authorship, and selective citing are examples of QRPs of concern to a broader representation of researchers within the social sciences. The potential implications in terms of content and quality of an instrumental research approach were identified as a QRP only within this field of research.

Idea Generation

The social sciences focus groups identified several QRPs relating to the idea or planning phase of the research process. A cross-cutting theme concerned the issue of strategic research. Both qualitative and quantitative researchers point to instrumental and marketable approaches to research as QRPs, where “projects and designs [are] tailored based on marketability rather than strict academic/research-related criteria/value” (QRP 12, SM). Furthermore, it is expressed as an instrumentalism that.

steers research with earmarked funds for specific things. This means that you are somehow forced to consider how you can make everything fit in. And I often find it extremely frustrating because the things you choose to discard are important. (Associate professor, law, focus group 16, p. 20)

The practice is seen as problematic, as it may force researchers to compromise on research relevance and quality, just as some topics may be ‘overexposed’ and others disregarded. A related QRP is fashion-determined choice of research topic, which contains the issue of some research areas being more or less dictated by norms in terms of what constitutes ‘cool research’. This QRP is, in contrast to the one above, seen as somewhat severe, but problematic nonetheless, as it “narrows the worldview” of the researcher and, in this particular case, the ability to produce “more general, cross-cutting theory” (QRP 5, SM). Lack of transparency about conflicts of interest is also mentioned as a QRP and concerns potential conflicts of interest that are not disclosed in connection with research applications (QRP 17, SM). Lastly, the concern about unoriginality is brought up in one of the qualitative social sciences groups and, like the humanities groups, refers to “half and fast” articles that do not bring anything new to the particular field of research (QRP 34, SM).

Research Design

Two QRPs are mentioned in connection with the process of designing research studies. The first is deselecting research-demanding methods that relates to “rejection of highly resource-intensive methods due to time pressure and funding considerations” (QRP 3, SM) and in this particular case concerns reinterpreting existing historical analyses rather than performing them from scratch. The other practice mentioned is considered to be very severe and rather prevalent and comprises the practice of designing research that may promote personal partisan agendas (politicization of one’s research, QRP 25, SM).

Data Analysis

The social sciences focus groups do not self-report any QRPs related to the process of collecting data. In turn, the practice of cherry-picking sources and data comes across as a predominant practice in the analytical phase and particularly within one of the qualitative focus groups that points to cherry-picking of interview quotations, legal sources, or other data to support a specific argument. This practice also emerges in one of the quantitative groups, where it is characterized as follows:

Imagine that you are doing a survey experiment and you have, let’s say, five conditions (…) it could be news items that may affect attitudes toward immigrants or something similar you found in the news media. Then there is an effect between two of them, and the three others are more blurry. Then you just muscle the three others out. And woops, they are no longer included in the analysis. (Assistant professor, political science, focus group 22, p. 14)

This practice is considered to be particularly problematic if the cherry-picking is not reported anywhere. Furthermore, it is a practice that is very much related to p-hacking, which is mentioned in one of the quantitative and one of the qualitative focus groups, where it relates to, respectively, a) the unduly influence of statistical analysis and b) the continuation of collecting person-centered internet data “until the desired item becomes significant” (QRP 23, SM).

Scientific Publication and Reporting

Selective reporting of research findings is identified as a QRP, but refers more specifically in one of the quantitative research groups to the difficulties of publishing no results (QRP 29, SM). Unfair assignment of authorship (QRP 33, SM) is given as an example of a questionable practice in both a quantitative and a qualitative group. In both instances, the practice of allocating co-authorships without providing any content to a given article is considered problematic. In the qualitative group, the example refers directly to Ph.D. students who help boost supervisors’ list of publications without the latter delivering any content to such co-authorships.

The questionable practice of “presenting research results in as many publications as possible”, i.e. salami slicing (QRP 27, SM), is also represented across both qualitative and quantitative research orientations. The same is evident for the practice of selective citing of existing and relevant sources, both in terms of one’s own work and others’ (QRP 28, SM).

Natural Sciences: Cherry-Picking Data and Lack of Validation

The natural sciences focus groups are represented by researchers with an experimental (two groups) or a theoretical orientation (two groups) in their research and include disciplines such as chemistry, biology, physics, mathematics, and geoscience (see Table 1). Similar to the technical sciences, the QRP of cherry-picking data and sources is a dominant example, in addition to questionable practices that relate to the lack of sufficient validation of results and difficulties in reproducing research findings (Table 7).

Idea Generation

Similar to the humanities and social sciences, unoriginality, understood as producing articles of little relevance, is also brought up as a QRP in two of the natural sciences focus groups. For instance, an associate professor in physics says,

People are simply producing 10 times too many to 50 times too many articles (…). They are just too similar. There are very few novel contributions. There is too much “belt and braces”, because people want to be sure that it’s accepted because it imitates well-merited and well-established research traditions. (Associate professor, physics, focus group 15, pp. 12–13)

In accordance with the general ranking of this QRP, it is perceived to be only somewhat severe, though creating a lot of noise and “interference on the line” (QRP 34, SM).

Research Design

As within the social sciences, the QRP of politicization of one’s research (QRP 25, SM) is presented as a very severe, but only somewhat widespread practice by a researcher who primarily links the imbrication between research and political views to observed examples within climate research. Inadequate use of methods is exemplified as using the wrong methods in computer programming and trying to translate methods used in medicine to natural science didactics in order to increase the status of the latter (QRP 11, SM).

Data Analysis

No QRPs are mentioned in relation to the research phase of collecting data. In terms of analyzing data, cherry picking sources and data is a predominant practice that is identified by both laboratory and theoretically oriented focus groups. It is referred to as “unreflected exclusion of data points that do not match the general pattern” or as omitting results that do not correspond with one’s theory, and it is seen as both prevalent and severe/rather severe (QRP 2, SM). Another distinct QRP, lack of validation, resembles the practice of cherry picking and refers particularly to a) lack of reproducibility, b) lack of controls of reproducibility, and c) disparity between theory and data, which makes a validation of results difficult (QRP 19, SM).

The third QRP mentioned, tuning and calibrating a method, remains within the theme of omitting important data and details, but refers in this case specifically to “tune or calibrate a method until it produces impressive results for one example, but then publishing it and claiming it solves a class of problems, while actually knowing that there are already examples where it fails” (QRP 32, SM).

Scientific Publication and Reporting

The theme of leaving out details recurs in the QRPs presented in relation to scientific reporting and dissemination of research results. The QRP lack of transparency in the use of methods and empirical data concerns the removal of important details from one’s articles, so that competitors are unable to conduct the same experiments (QRP 18, SM). The same laboratory/experimental focus group provides two examples of the practice of overgeneralizing results, which are a) increasing the impact of a study by “translating data from animal models to apply to humans”, and b) “upscaling far beyond the measuring field”, for instance by multiplying a few square meters, making them apply to an entire ecosystem (QRP 21, SM). Both examples are seen as severe, but only somewhat prevalent.

As within the social sciences, salami slicing (QRP 27, SM) is presented in one of the laboratory groups as a very prevalent, but only somewhat severe practice of ‘slicing’ one’s measurements and results into several publications instead of only one. Unfair assignment of authorship also figures as a QRP, and an associate professor in geoscience points to the potentially questionable practice of adding too many authors to a paper, questioning the actual contribution of all co-authors (QRP 33, SM).

Discussion

In the words of Pickersgill, “science today is an ‘ethical’ business” (2012, 579), and research institutions, governmental agencies, and research communities have particularly within the last decades, following the so-called ‘reproducibility crisis’ in science (Resnik & Shamoo, 2017) implemented mechanisms, actions, legislation, guidelines, and codes of conduct to promote research integrity and mitigate irresponsible conduct of research. The world has seen global and aspirational statements such as the Singapore Statement on Research Integrity (2010), the Montreal Statement on Research Integrity in Cross-Boundary Research Collaborations (2013), and the Hong Kong Principles for Assessing Researchers (2020), and national and international bodies have been established to advise on, oversee, and foster responsible research. In Europe, the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (ALLEA, 2017) has been especially influential. Nonetheless, while such efforts are meant to promote and harmonize research integrity practices, cross-country heterogeneity still characterizes national and institutional endeavors to raise awareness, educate, and implement research integrity actions. Research misconduct and QRP allegations procedures also vary greatly within and among countries (Godecharle et al., 2014; Jensen, 2017).

In addition to national or geographical diversity, we argue that disciplinary variations should be taken into account. When it comes to QRPs, so far, as mentioned above, mainly the behavioral and biomedical sciences have been investigated (e.g. Anderson et al., 2007; Hofmann & Holm, 2019; John et al., 2012; Steneck, 2006). In the literature, QRPs are often referred to as something in themselves, as QRPs per se. However, a main finding in our study is that we have to start focusing more on disciplinary differences in QRPs and the perception hereof. Our results clearly show that despite some similarities there are significant differences between the main areas of research that need to be taken into account in future studies of QRPs as well as in research integrity policy formulations.

In our focus group interviews, the participants mentioned 107 examples of detrimental practices. In the analysis, these examples could be reduced to 34 QRPs. As Table 8 shows, 19 of the 34 QRPs were only reported within one main area of research, which testifies to variances between the different areas (see Appendix 2for a list of QRPs). However, 15 of the 34 QRPs were reported in at least two areas, which also points to some similarities between the main areas. Three QRPs—selective citing, selective reporting of research findings, and unoriginality—were discussed in three different main areas, while four QRPs were discussed across four main areas: unfair assignment of authorship, p-hacking, lack of validation, and inadequate use of methods. Only one QRP was discussed in all main areas of research, namely cherry picking sources and data.

While these QRPs may be said to provide only a snapshot of the practices that come to mind during focus group discussions on the ‘gray areas’ of conducting research, the ease with which the practices emerged as well as the results of the ranking exercise and the discussion of these practices during the interviews demonstrate the importance the interviewees attached to the individual practices reported. The number of areas in which the different QRPs were discussed can also to some extent be explained by variances in practices. For example, when unfair assignment of authorship is discussed in all main areas, except for the humanities, this can be explained by authorship practices within the humanities, where authors are typically mentioned in alphabetic order, where many publications are single-authored, and where publications on average have fewer co-authors than publications within other areas (Henriksen, 2016). However, the fact that the social sciences as the only area did not discuss lack of validation and inadequate use of methods probably testifies to limitations within our method rather than to differences in practices.

One must therefore be cautious not to make too far-reaching conclusions on the basis of the practices that were not mentioned in the focus groups. For the same reason, we do not find that this study can contribute with conclusions on where in the research process the QRPs occur—or do not occur. It should be mentioned, though, that neither the medical nor the technical sciences mentioned any QRPs related to the idea generation phase of the research process, and that the social and natural sciences likewise did not report any QRPs occurring in the data collection phase. This probably does not mean that QRPs cannot be found within these phases of the research process within these research areas. Instead, it probably means that the greater part of the problems within these areas are to be found in other phases of the research process, and here the social and natural sciences seem to differ. The social sciences report more problems in the idea generation and design phases, whereas there is an accumulation of QRPs in the later phases of the research process in the natural sciences (analysis and reporting phases). In the humanities, there is a more equal distribution of QRPs between the different phases, though with a majority of the QRPs occurring in the data analysis phase. In the medical sciences, most QRPs are found in the analysis and reporting phases, and in the technical sciences, the reporting phase together with the design and analysis phases contain most of the reported QRPs.

If we take a closer look at the QRPs that were reported in the interviews, an important finding is that even though the names of the QRPs in many cases are the same across main areas of research, the understanding of the QRPs’ relevance, severity, and prevalence often differs between the research areas. This supports the relevance of the notion of epistemic cultures, also when it comes to QRPs. According to the idea of epistemic cultures, there is no unity of the sciences (Knorr Cetina, 1999; Knorr Cetina & Reichmann, 2015). Instead, the sciences “are differentiated into cultures of knowledge that are characteristic of scientific fields or research areas, each reflecting a diverse array of practices and preferences” (Knorr Cetina & Reichmann, 2015, 873). This lack of unity is evident from our study, and as shown in the results section, the variation in QRP perceptions is closely related to variations in research practices and notions of what constitutes good research. Fishing is an example of how different perceptions can be. In the medical sciences, fishing, understood as looking at data without a plan, is considered a detrimental practice, although a rather prevalent one. In other types of research, especially within the humanities, continuous exploration of data is a common and unproblematic practice. Examples include scholars within literature, who examine classic texts and make new, original analyses of them or historians, who return to already examined historical material in order to get a better understanding of an historical event or period. This shows the close relation between perceptions of QRPs and the diverse norms and practices of the different main areas of research.

Interestingly, our findings also show that these differences sometimes exist within a single research area and not between areas. The five main areas of research used in our study the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, medical sciences, and technical sciences all contain many different disciplines and subfields, often with very diverse practices and understandings of what good research is. In line with Knorr Cetina and Reichmann (2015, 876), our findings show that a subfield of one main area of research can have more in common with subfields from other areas of research than with other subfields within its own area. In our study, we saw this with p-hacking, for example. At first sight, the discussion of p-hacking within the humanities in the previous section may appear somewhat surprising. Nonetheless, humanities scholars from the discipline of sociolinguistics regularly apply statistical methods in their research, and much like researchers within the social, technical, and medical sciences they pointed to the detrimental effects of chasing significance.

At the same time, it should be noted that the same QRPs often cover many different practices, related to variances in the methods applied in different subfields. An interesting example of this is cherry picking of data, which was the only QRP mentioned within all areas of research. It typically refers to the practice of excluding particular data points and the removal of outliers within quantitative research, but in qualitative research it can also be understood as a biased selection of, for example, legal sources and interview quotations, as shown above.

In conclusion, this means that not only is there no unity in the creation and justification of science (Knorr Cetina, 1999), there is neither a unity in QRPs. These findings support the idea that we have to consider disciplinary differences when implementing policies and procedures for research integrity in research institutions (Mejlgaard et al., 2020). QRPs are always related to a particular research practice, and the understanding of how detrimental they are is further related to the professional standards and norms of a given discipline.

Notes

This focus group study is part of the PRINT project (Practices, Perceptions, and Patterns of Research Integrity, preregistered at the OSF: https://osf.io/rf4bn/). The PRINT project also consists of a wide-ranging survey study and a number of more detailed studies on the categorizations, causes, and mechanisms of QRPs. Results from these studies will be presented in separate publications, while the findings on QRP perceptions and practices from the focus group study are the focal point of this article.

Two–three disciplines within each of the five main areas were represented in each focus group. The selection of disciplines was based on a list of disciplinary fields within the main areas represented at the Danish universities compiled by the ministry and revised by DKUNI in 2017.

The numbering of the focus groups go beyond 22 because some of the planned focus groups had to be cancelled due to too few participants. These groups were reorganized, rescheduled and assigned a new number.

Prevalence was coded according to the five categories: not prevalent, somewhat prevalent, prevalent, rather prevalent, very prevalent. Severity was coded according to the five categories: not severe, somewhat severe, severe, rather severe, very severe.

References

ALLEA (2017). The European code of conduct for research integrity. Revised Edition. https://allea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ALLEA-European-Code-of-Conduct-for-Research-Integrity-2017.pdf

Anderson, M. S., Martinson, B. C., & de Vries, R. (2007). Normative dissonance in science: Results from a national survey of U.S. scientists. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 2(4), 3–14

Anderson, M. S., Ronning, E. A., DeVries, R., & Martinson, B. C. (2010). Extending the Mertonian norms: Scientists’ subscription to norms of research. Journal of Higher Education, 81(3), 366–393

Anderson, M. S., Shaw, M. A., Steneck, N. H., Konkle, E., & Kamata, T. (2013). Research integrity and misconduct in the academic profession. In M. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research.Springer.

Banks, G. C., O’Boyle, E. H., Pollack, J. F., White, C. D., Batchelor, J. H., Whelpley, C. E., Abston, K. A., Bennett, A. A., & Adkins, C. L. (2016). Questions about questionable research practices in the field of management: A guest commentary. Journal of Management, 42(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315619011

Bo, I. G. (2005). At sætte tavsheder i tale: fortolkning og forståelse i det kvalitative forskningsinterview. In M. H. Jacobsen, S. Kristiansen, & A. Prieur (Eds.), Liv, fortælling og tekst: Strejftog i kvalitativ sociologi. Aalborg University Press.

Bouter, L. M., et al. (2016). Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: Results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Research Integrity and Peer Review. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5

Bouter, L. (2020). What Research institutions can do to foster research integrity. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26, 2363–2369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00178-5

Butler, N., Delaney, H., & Spoelstra, S. (2017). The gray zone: Questionable research practices in the business school. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(1), 94–109

Dal-Réet, R., Bouter, L. M., Cuijpers, P., Gluud, C., & Holm, S. (2020). Should research misconduct be criminalized? Research Ethics, 16(1–2), 1–12

Davies, S. R. (2019). An ethics of the system: Talking to scientists about research integrity. Science and Engineering Ethics, 25, 1235–1253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-018-0064-y

Fanelli, D. (2009). How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A Systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE, 4(5), e5738

Fleck, L. (1979). Genesis and development of a scientific fact. T. J. Trenn & R. K. Merton (Eds.). “Foreword” by T. S. Kuhn. Chicago University Press

Godecharle, S., Fieuws, S., Nemery, B., et al. (2018). Scientists still behaving badly? A survey within industry and universities. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24, 1697–1717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9957-4

Godecharle, S., Nemery, B., & Dierickx, K. (2014). Heterogeneity in European research integrity guidance: Relying on values or norms? Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 9(3), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264614540594

Halkier, B. (2016). Fokusgrupper. (3rd ed.). Samfundslitteratur.

Hall, J., & Martin, B. R. (2019). Towards a taxonomy of research misconduct: The case of business school. Research Policy, 48(2), 414–427

Haven, T., Tijdink, J., Pasman, H. R., et al. (2019). Researchers’ perceptions of research misbehaviours: A mixed methods study among academic researchers in Amsterdam. Research Integrity and Peer Review. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-019-0081-7

Henriksen, D. (2016). The rise in co-authorship in the social sciences (1980–2013). Scientometrics, 107, 455–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1849-x

Hofmann, B., & Holm, S. (2019). Research integrity: Environment, experience or ethos? Research Ethics, 15(3–4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016119880844

Horbach, S. P. J. M., & Halffman, W. (2019). The extent and causes of academic text recycling or ‘self-plagiarism.’ Research Policy, 48(2), 492–502

Jensen, K. K. (2017). General introduction to responsible conduct of research. In: K. Klint Jensen, L. Whiteley, & P. Sandøe (Eds.), RCR: A Danish textbook for courses in Responsible Conduct of Research (pp. 12–24). Frederiksberg: Department of Food and Resource Economics, University of Copenhagen

John, L. K., Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (2012). Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychological Science, 23(5), 524–532

Knorr Cetina, K. & Reichmann, W. (2015). Epistemic cultures. In International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (2nd ed.) (pp. 873–880)

Knorr-Cetina, K. (1999). Epistemic cultures: How the sciences make knowledge. Harvard University Press.

Lamont, M. (2009). How professors think: Inside the curious world of academic judgment. Harvard University Press.

Martinson, B., Anderson, M., & de Vries, R. (2005). Scientists behaving badly. Nature, 435, 737–738

Mejlgaard, N., Bouter, L. M., Gaskell, G., Kavouras, P., Allum, A., Bendtsen, A.-K., Charitidis, C. A., Claesen, N., Dierickx, K., Domaradzka, A., Reyes Elizondo, A. E., Foeger, N., Hiney, M., Kaltenbrunner, W., Labib, K., Marušić, A., Sørensen, M. P., Ravn, T., Ščepanović, R., … Veltri, G. A. (2020). Research integrity: nine ways to move from talk to walk. Nature, 586, 358–360

Moher, D., Bouter, L., Kleinert, S., Glasziou, P., Sham, M. H., Barbour, V., et al. (2020). The Hong Kong principles for assessing researchers: Fostering research integrity. PLoS Biology, 18(7), e3000737. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000737

Montreal Statement on Research Integrity in Cross-Boundary Research Collaborations. (2013). Developed as part of the 3rd World Conference on Research Integrity. https://wcrif.org/montreal-statement/file

Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage Publications.

National Academies of Science. (2017). Fostering integrity in research. National Academies Press.

National Academy of Science. (1992). Responsible science: Ensuring the integrity of the research process. National Academy Press.

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Penders, B., Vos, R., & Horstman, K. (2009). A question of style: Method, integrity and the meaning of proper science. Endeavour, 33(3), 93–98

Pickering, A. (1992). From science as knowledge to science as practice. In A. Pickering (Ed.), Science as practice and culture. (pp. 1–28). University of Chicago Press.

Pickersgill, M. (2012). The co-production of science, ethics, and emotion. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 37(6), 579–603

Resnik, D. B., & Shamoo, A. E. (2017). Reproducibility and research integrity. Accountability in Research, 24(2), 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2016.1257387

Schwartz-Shea, P., & Yanow, D. (2012). Interpretive research design: concepts and processes. Routledge.

Shaw, D. (2016). The trojan citation and the “accidental” plagiarist. Bioethical Inquiry, 13, 7–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-015-9696-7

Shaw, D. (2019). The quest for clarity in research integrity: A conceptual schema. Science and Engineering Ethics, 25, 1085–1093. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-018-0052-2

Singapore Statement on research integrity. (2010). World Conference on Research Integrity (Drafting Committee: N. Steneck, T. Mayer, M. Anderson et al.). 2nd and 3rd World Conference on Research Integrity. https://wcrif.org/statement

Steneck, N. H. (2006). Fostering integrity in research: Definitions, current knowledge, and future directions. Science and Engineering Ethics, 12(1), 53–74

Tijdink, J. K., Verbeke, R., & Smulders, Y. M. (2014). Publication pressure and scientific misconduct in medical scientists. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 9(5), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264614552421

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the PRINT team, especially Jesper W. Schneider, who as PI of the PRINT project invited us to conduct the focus group study. Jesper also kindly commented on an earlier version of this paper. Together with Jesper, Niels Mejlgaard and Kaare Aagaard also deserve a special thanks for many inspirational discussions on the design and methodology of this study. Jesper, Niels, and Kaare also performed the facet analysis of Bouter et al.’s (2016) list of 60 QRPs that led to the eight prewritten cards/QRPs used in the focus group interviews. We would also like to thank Serge Horbach for his very inspirational comments to a previous version of the paper. We would further like to thank Alexander Kladakis, Asger Dalsgaard Pedersen, and Pernille Bak Pedersen for their invaluable help with organizing the interviews, and Anna-Kathrine Bendtsen, Signe Nygaard, Trine Byg, Astrid Marie Kierkgaard-Schmidt, Anders Møller Jørgensen, and Massimo Graae Losinno for transcribing the interviews. Finally, we would like to thank the 105 interviewees, who took part in this study: Thank you for sharing your experiences and understanding of QRPs with us!

Funding

This work has been supported by the PRINT project (Practices, Perceptions, and Patterns of Research Integrity) funded by the Danish Agency for Higher Education and Science (Ministry of Higher Education and Science) under Grant No 6183-00001B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author names are in alphabetic order. Except for the coding of the interviews, which was performed by TR, all parts of this study—design, interviewing, and analysis as well as the writing of this article have been done by the two authors in close cooperation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Appendix

Appendix

Appendix 1: Specifications on Research Design

The focus group interviews were conducted by the authors collectively as co-moderators and took place in October, November, and December 2017 at eight universities in Denmark: University of Copenhagen, Aarhus University, Technical University of Denmark, Copenhagen Business School, Roskilde University, Aalborg University, University of Southern Denmark, and the IT University of Copenhagen.

The focus group interview was chosen as method because of its strength in producing data on complex and uncharted empirical subject matters that detail practices, group interpretations, norms, and assessments (Halkier, 2016; Morgan, 1997). Moreover, this method allowed us to discuss issues of a potentially sensitive character and to gain insights into researchers’ perceptions of the gray areas of conducting research.

Selection and Recruitment of Focus Group Participants

To ensure that the interviewees would understand each other’s work and ways of doing research and could be expected to have similar views on what constitutes good and bad research practices, respectively we primarily focused on the participants’ research practices, i.e. on ‘how science is done’, when composing the groups as described in the Methods section.

Further selection criteria impinge on the number of interview participants. Each focus group had to consist of a minimum of four and a maximum of six participants with a balanced gender composition. Two to three sub disciplines within each of the five main research areas should also be represented in each focus group, and the selected disciplines should cover all major subfields of the five main areas (e.g. political science, economics, law, and psychology within the social sciences).

The selection of interviewees was based on an ‘information-oriented’ (Bo, 2005, 71) selection strategy with the objective to reach a broad group of researchers from different main and subfields. Generally, the focus group literature points to sample homogeneity as the most effective composition strategy in terms of group dynamics due to the presence of a common frame of reference (Halkier, 2016; Morgan, 1997). This is the predominant rationale for choosing segmented groups, according to the selection strategy of ‘how science is done’, epitomized as variation in research practices and knowledge production models. At the same time, we wished to introduce some heterogeneity into the groups in order to create a balance between recognisability and knowledge exchange, as too much homogeneity may cause shared knowledge to be taken for granted and left unsaid during focus group discussions. We established diversity by ensuring that the groups were composed of both men and women and by including researchers at stratified career levels (which is likely to correspond to the variation in age too): postdoc/assistant professor, associate professor, and professor. Furthermore, while we wished to establish a setting of optimal interaction conditions, we also wished to pursue group variation to gain in-depth understandings and to foster a group dynamic from which it would be possible to elicit differences in QRP perceptions and practices as well as differences in terms of potential causes (individual, institutional, societal, etc.). As a sample criterion, we avoided senior/junior constellations from the same institute in order to reduce participants’ reticence to speak openly. Likewise, we strived to recruit people with no prior research collaborations.

The recruitment of focus group participants was based on a combination of strategies. To increase credibility and variation, we aimed to conduct purposeful random sampling (Palinkas et al., 2015) by systematically trawling university webpages of the selected disciplines, commencing from the top of the lists of researchers, selecting researchers that met our criteria. Concurrently, we informed heads of department that we were going to recruit participants for our study, and that we would be contacting employees via their public university emails. A snowball/chain sampling strategy supplemented the strategy of searching webpages, and we used our own network to find potential interview participants not known to the interviewers. Recruiting participants for such a large-scale focus group study with 22 focus groups was challenging, and we invited a total of 808 researchers. Each focus group had three to six participants, and a total of 105 researchers took part in the study.

Interview Design

The moderator guide was structured as a ‘funnel model’ (Halkier, 2016). After an introduction explaining the purpose of the study, communicating the interview guidelines, and introducing the participants, each interview opened with an explorative question inquiring into the participants’ thoughts on what constitutes a good or favorable research process and examples hereof. The discussion then moved on to the subject of QRPs, and the participants were asked to list challenges, if any, in upholding good research practices within their field of research. Before further exploring the pre-defined themes of QRP causes and developments, we spent a third of the scheduled time doing a ranking exercise. First, the participants were asked to write down a severe or prevalent QRP within their area of research. Then they were given eight pre-written cards with pre-defined QRPs and, based on group discussions and negotiations, asked to place the pre-written cards as well as their own cards on a simple QRP ‘severity scale’ ranging from ‘not severe’ to ‘severe’ to ‘very severe’. The participants were told that the scale covered the ‘gray area’ between RCR and FFP. We did not provide further specifications of the concept of severity prior to the exercise, as we wanted to encourage extempore researcher understandings of the particular “objects” exposed to harm, such as individual researchers and their careers, particular research projects or research fields or science in general in terms of research beneficiaries, general trust in science etc. After this first part of the exercise and a short break, the interviewees were asked to rank the same cards on a ‘prevalence scale’. Again, we used a very simple scale ranging from ‘not prevalent’ to ‘prevalent’ to ‘very prevalent’. The eight QRP examples used are well-known QRPs in the literature. To arrive at these particular eight examples, the 60 QRP examples in Bouter et al. (2016) were sorted and categorized into a smaller number of practices using facet analysis. The final set of eight QRPs were then selected based on an assessment of their importance and resonance within and across the different fields of research. The eight QRPs are: lack of transparency in the use of methods and empirical data; selective reporting of research findings; salami slicing; p-hacking and/or HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known); selective citing; unfair assignment of authorship; unfair reviewing; inadequate data management and data storage.

The rationale for including the exercise, and especially for using the eight pre-written cards in all groups, was to gain an understanding of how different disciplinary research fields assess the prevalence and severity of different QRPs. Through participant deliberations, we also wanted to gain insight into their understanding of the different QRPs (e.g. what selective reporting of research findings or unfair assignment of authorship could mean within different fields). The exercise also created a structured, though dynamic and creative space for lively discussions that, presumably, produced comparable knowledge that might have been difficult to elicit otherwise.

Coding and Analysis Strategy