Opinion statement

Restless Legs Syndrome/Willis-Ekbom Disease (RLS/WED) is a common condition characterized by an irresistible urge to move the legs, concomitant with an unpleasant sensation in the lower limbs, which is typically relieved by movement. Symptoms occur predominantly at rest and prevail in the afternoon or evening. Treatment of patients with RLS/WED is indicated for those patients who suffer from clinically relevant symptoms. The management of mild forms of RLS/WED is mainly based on dopamine agonists (DA) therapy (including pramipexole and ropinirole) and α-2-δ calcium-channel ligand. Nevertheless, with passing of time, symptoms tend to become more severe and the patient can eventually develop pharmacoresistance. Furthermore, long-term treatment with dopaminergic agents may be complicated by the development of augmentation, which is defined by an increase in the severity and frequency of RLS/WED symptoms despite adequate treatment. Here, we discuss which are the best therapeutic options when RLS/WED becomes intractable, with a focus on advantages and side effects of the available medications. Prevention strategies include managing lifestyle changes and a good sleep hygiene. Different drug options are available. Switching to longer-acting dopaminergic agents may be a possibility if the patient is well-tolerating DA treatment. An association with α-2-δ calcium-channel ligand is another first-line approach. In refractory RLS/WED, opioids such as oxycodone–naloxone have demonstrated good efficacy. Other pharmacological approaches include IV iron, benzodiazepines such as clonazepam, and antiepileptic drugs, with different level of evidence of efficacy. Therefore, the final decision regarding the agent to use in treating severe RLS/WED symptoms should be tailored to the patient, taking into account the symptomatology, comorbidities, the availability of treatment and the history of the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Restless Legs Syndrome/Willis-Ekbom Disease (RLS/WED) is a common sensorimotor disorder with a prevalence ranging from 5.5 to 11.6 %. It is characterized by uncomfortable and unpleasant sensations mainly in the lower limbs, with an urge to move the legs. Symptomatology usually begins or worse during period of rest or inactivity and may be relieved by activity. The disorder typically has a circadian rhythm as RLS/WED symptoms tend to worsen in the evening or during the night [1••]. The presence of periodic limb movements (PLM), positive familial history of RLS/WED and a prompt response of symptoms to dopaminergic therapy are used as supportive data for diagnosis [2•].

RLS/WED typically manifests itself as a chronic condition requiring long-term treatment. Several drugs showed efficacy. Currently, the first-line treatment options are dopamine agonists, with pramipexole, ropinirole and rotigotine recognized as the most commonly prescribed. Alpha-2-delta agonists like gabapentin, gabapentin enacarbil and pregabalin are now becoming a plausible alternative [3]. Another possible treatment for the treatment of RLS/WED is represented by opioids that are not frequently recommended because of their side effects and concern for possible misuse [4•].

In spite of an initial amelioration, re-emergent or worsening RLS/WED symptoms over time are commonly described. In a recent survey among treated patients, Tzonova et al. found that 41 % reported repeated daytime symptoms occurring day by day [5]. When facing worsening of RLS/WED symptoms, clinicians have first to investigate in subject’s health or lifestyle that could explain this worsening or the use of medication known to be possible trigger for RLS/WED symptoms. Identifying these factors is important in order to avoid unnecessary changes in the existing medication [3].

If no significant explanation for worsening of symptoms is found by inquiry, clinician should consider different scenarios, such as loss of efficacy, tolerance and augmentation. Loss of efficacy concerns to the reappearance of RLS/WED symptoms similar to those encountered before treatment, after an initial positive response. This could be the consequence of the intrinsic development of RLS/WED, which tends to worsen over time [6]. Vice versa, augmentation is an iatrogenic worsening of symptoms that occurs during treatment with dopaminergic drugs. It is characterized by an earlier onset of symptoms, which occur frequently during the day, than before the beginning of the treatment. Moreover, amplified severity of symptomatology, decreased period to symptom onset with immobility and shortened treatment’s efficacy could be noticed [7].

Dopaminergic agents have a good efficacy in most patients and are therefore considered the first-line intervention. Nevertheless, due to the possible iatrogenic worsening of symptomatology, the possibility of developing clinically resistant symptoms and the risk of developing severe forms of impulse control disorder (ICD), the physician must be familiar with second-line treatments in order to settle the best approach when facing an intractable or resistant form of RLS/WED.

The aim of our work is therefore to review the current pharmacological options for RLS/WED treatment, with a focus on intractable RLS/WED. Furthermore, non-pharmacological interventions (i.e. behavioural treatment, transcranic stimulation) will be discussed.

Dopamine agonists

Since the serendipitous observation in 1982 by Akpinar of the benefit of levodopa for RLS, dopamine agonists have been the first line of treatment [8]. They have a well-demonstrated efficacy in relieving symptoms of RLS and improving sleep [9••, 10]. Unfortunately, patients on a long-term treatment with dopamine agonists (DA) can develop loss of efficacy. If worsening of symptoms occur with one agent, it is advisable to try another DA. DAs alleviate symptoms in up to 70 % of patients [11].

Pramipexole is the most frequently used oral agent. It has a time to reach maximum concentration (tmax) of 2 h, with a terminal half-life of 8–12 h.

Compared to pramipexole, Ropinirole has a more rapid onset of action (tmax = 1 h) and a shorter duration of action (terminal half-life = 6 h). Both pramipexole and ropinirole have demonstrated efficacy, and the choice of one agent over the other depends on tolerability.

Rotigotine is a dopamine agonist which comes in the form of a transdermal patch, provides stable plasma concentrations throughout the day. Its continuous delivery system makes this agent particularly useful for patients with daytime symptoms or after the failure of oral therapies. In a study by Takahashi et al., 81 patients with daytime RLS symptoms displayed a significant reduction of daytime symptom duration with rotigotine treatment compared with placebo (p = 0.03) [12]. The effectiveness of pramipexole, ropinirole and rotigotine in the treatment of RLS/WED has been established for up to 6 months (Level A) [9••].

Levodopa is used occasionally as a rescue medication when symptoms are anticipated but has a high frequency of side effects (60–80 % of augmentation) [13]. It has been established as probably effective (Level B) for durations ranging from 1 to 5 years [9••].

Subcutaneous injections of the potent dopamine-D1/D2 receptor agonist apomorphine have been reported to be effective in selected cases [14]. A dose of 1 mg was sufficient to control RLS symptoms when applied at night time.

The use of pergolide and cabergoline is burdened by relevant side effects, such as valve heart fibrosis thickness and pulmonary fibrosis; therefore, they are not recommended unless the benefits of their use clearly outweigh the risks [9••].

A troublesome complication of dopaminergic agents is augmentation, a relevant clinical issue that emerges after the long-term treatment of RLS/WED. Augmentation has been assumed to occur with dopaminergic treatment rather than to be a natural progression of the disease [15]. Unlike loss of efficacy, dose increases exacerbate augmentation, and usually, RLS symptoms are worse than before treatment [6].

Augmentation is more frequent during treatment with levodopa or with shorter-acting dopamine-receptor agonists, but all DA can cause some level of augmentation [9••].

Several preventative measures can be used to avoid augmentation. The most helpful approach is to use the lowest effective dose. Subdividing the dopaminergic dose, administering one dose before and one after the symptoms onset, can be also of use.

When these measures are unsuccessful, a different DA may be prescribed. If the patient is using a short-acting DA, it can be shifted to a longer-acting molecule. For severe or progressive augmentation, the dopaminergic dose should be tapered down, and in the same time, a non-dopaminergic treatment should be started.

Most common side effects with DA are sleepiness and ICD such as compulsive gambling, hyper sexuality, punding, compulsive shopping or binge eating. All patients should be warned about the possibility of ICDs prior to a starting dopaminergic treatment [16].

Alpha-2-delta calcium-channel ligands

Alpha-2-delta agonists such as gabapentin, gabapentin enacarbil and pregabalin are, in many countries, available as off-label treatments for RLS/WED. These agents are particularly advantageous since they are not associated to augmentation or to ICD.

A recent double-blind study with 719 patients with primary RLS compared pregabalin, pramipexole and placebo. The efficacy of pregabalin was superior to placebo and comparable with the dopamine agonist [17]. Furthermore, the authors noted an augmentation rate of 1.7 % over a 52-week period, compared to 6.6–9.0 % with pramipexole. Pregabalin has been established as effective for up to 1 year in treating RLS/WED (Level A evidence) [9••].

Gabapentin enacarbil has been established as probably effective (Level B) in treating RLS/WED for durations ranging from 1 to 5 years [9••].

If the patient has symptoms that cannot be controlled with a low-dose monotherapy of a dopamine-receptor agonist or an alpha-2-delta ligand, a combination of treatments should be considered [9••].

A possible side effect of alpha-2-delta agents is dizziness or gait instability at the beginning of treatment, along with weight gain with prolonged treatment.

Opioids

Patients with painful symptoms can benefit from the use of opioid agents such as oxycodone, propoxyphene, tramadol or codeine. These are not frequently used as initial approach due to concerns regarding misuse potential and side effects (e.g. respiratory depression, constipation and sleepiness). Prudence should be used when prescribing these agents to patients with a history of substance abuse.

An extended-release oxycodone–naloxone combination has recently demonstrated efficacy in improving of RLS/WED symptoms when dopamine agents are not effective [18••, 19]. The response to this treatment has been one of the most effective ever seen in RLS/WED.

Low-dose methadone is used in the USA and is effective for long-term management. A decrease in the testosterone levels has been reported, possibly leading to decreased libido, depression or nocturnal sweating [20, 21].

The occurrence of augmentation with chronic use of tramadol has been reported [22].

If the use of oral opioids is limited due to side effects, the intrathecal administration of morphine may be considered. In a Class IV evidence study, intrathecal morphine (MSI) was given through an indwelling lumbar catheter with a programmable pump. RLS symptoms were significantly relieved, and the dopaminergic medication could be tapered [23].

Tapering or stopping chronic opioids may determine worsening of RLS/WED symptoms [24]. If this decrease is otherwise wanted, temporary use of a dopaminergic agent may be appropriate.

According to the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG), evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on the use of tramadol, methadone or morphine in the treatment of RLS/WED refractory to other treatments. However, we can consider the high-potency opioids like methadone or as possibly effective (Level C) in the long-term treatment of intractable RLS/WED [9••].

Overall, opioids are a reasonable therapeutic choice for patients with resistant symptoms, particularly oxycodone and methadone [21, 25, 26].

Frequent side effects of prolonged opioids use include sedation, respiratory depression, constipation, endocrine disorders and cardiovascular alterations (decreases in heart rate, blood pressure, inotropy and cardiac output) along with the risk of development of tolerance and dependence.

Other pharmacological agents

The association between iron deficiency and RLS/WED is well known, although its pathophysiology has never been fully elucidated [22]. The role of IV iron as a therapy for RLS has therefore become a major clinical research interest.

Studies revealed that iron supplementation can improve RLS/WED symptoms even in patients with low–normal ferritin [27]. Nevertheless, oral iron has limited benefit, since iron absorption across the intestinal epithelium into the blood is limited, especially in those without iron deficiency [27]. Subsequently, infusion of IV iron may provide significant therapeutic advantage.

High molecular weight iron dextran is no longer available due to its unacceptable toxicity rate [28•]. On the other hand, low molecular weight iron dextran has proved to be safer. A study by Auerbach et al. did not find any serious adverse events in a sample of 888 patients receiving 1266 infusions [29]. IV low molecular weight iron dextran significantly improves RLS symptoms in a majority of patients, usually within the first 24–48 h [30, 31]. The efficacy and safety of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose with RLS/WED was recently confirmed also in a sample of pregnant women with iron deficiency or anaemia [32].

Even though evidence is still insufficient to make a recommendation on the intravenous use of ferric carboxymaltose or iron sucrose in the long-term treatment of RLS/WED, supplementation with orally administered iron is recommended if the patient’s serum ferritin level is lower than 75 μg/mL, unless poorly tolerated or contraindicated [9••, 33]. Furthermore, low iron stores have been related to an increased risk of augmentation, thus an appropriate iron supplementation should be given in these cases [34••].

The mechanism of action of Benzodiazepines depends on the CNS depression, via the receptor for the gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA). Benzodiazepines have shown to decrease the number of arousals due to PLMS, hence improving sleep [35]. They can be taken orally when going to sleep or shortly before. The complication of this treatment is the possible development of tolerance and dependency, which may be relevant upon long-term treatment. In order to avoid withdrawal symptoms, therapy should not be discontinued abruptly. Benzodiazepines can be of use in the management of refractory RLS/WED as an add-on to DA treatment.

Antiepileptic drugs, such as lamotrigine, carbamazepine, levetiracetam and valproate, have been also suggested as possible treatment for RLS/WED. The efficacy of their use is very limited, since studies included only a limited number subjects or were open label.

The use of sedative hypnotics (e.g. Clonazepam [36]) or antiepileptic drugs (e.g. levetiracetam [37]), therefore, is not supported by adequate level of evidence in the long-term treatment of RLS/WED.

Non-pharmacological treatments

Currently, licensed first line of treatment with dopaminergic agents is complicated by the phenomenon of augmentation and by several side effects such as ICD. If treatment with other agents such as gabapentin or pregabalin is not effective or available, non-pharmacological treatments represent for the clinician an opportunity to improve their therapeutic inventory with fewer side effects.

In 2006, Aukerman et al. evaluated the efficacy of an exercise programme on RLS/WED. Participants were assigned to exercise (a programme of aerobic and lower-body resistance) or control group. After 12 weeks, the exercise groups showed significant improvement in RLS/WED symptoms compared to control group. The authors stated that their findings support the use of exercise as an adjunction to RLS/WED drug treatment [38]. Recently, another study investigated the effects of a 6-month exercise training in dialysis patients with RLS. Fourteen patients were randomized to the exercise training plus dopamine agonist group and the exercise training plus placebo group. In both conditions, a significant decrease of RLS symptomatology was observed. The authors claimed that low dose of DA combined with exercise training could be considered as an alternative approach to high dosage DA in reducing RLS/WED symptoms’ severity [39•].

To test the possibility of increasing coping strategies and quality of life in subjects affected by RLS/WED, Hornyak et al. developed a psychologically based group therapy approach created specifically for this disorder [40]. A pre-post comparison was performed, with no control group. After treatment, the RLS-related quality of life, mental health status and the subjective rating of RLS symptoms showed a significant improvement. These results underline the possibility toward an integrated approach for RLS/WED treatment.

Also, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has been employed to test beneficial effects in RLS/WED. rTMS is a non-invasive technique used to modify cortical excitability and suggested for the treatment in both brain hyperexcitability or hypoexcitability disorders. Lin et al. [41] administered high frequency rTMS to the leg representation motor cortex area of the frontal lobe of 14 RLS/WED patients for 14 sessions over 18 days. After the 14th session, a significant amelioration was observed at the International RLS Rating Scale (IRLS-RS), with the effects lasting more than 2 months.

A different non-invasive brain stimulation technique, transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) was used to evaluate its efficacy in drug naïve RLS/WED patients. They were assigned to receive cathodal, anodal or sham stimulation on the primary sensorimotor area. After treatment, no significant differences between the three groups were found [42•]. More promising results were obtained by the employment of transcutaneous spinal direct current stimulation (tsDCS). tsDCS is a painless way to modulate spinal cord activity. Since the pathophysiology concept of RLS/WED proposes an increased spinal excitability, Heide et al. [43] evaluated the application of tsDCS as a new therapy in this pathology. Specifically, they verified if anodal tsDCS is capable to alleviate the severity of RLS symptoms and if this improvement is associated with inhibitory effect on spinal pathways. 20 RLS/WED patients and 14 controls were enrolled in this study. One session of cathodal, anodal or sham stimulation of the spinal cord (15 min, 2.5 mA) was administered in the evening when patients exhibit an exacerbation of their symptomatology. Results showed a significant reduction in RLS/WED symptoms after application of anodal and cathodal stimulation. Furthermore, anodal stimulation provoked a reduced H2/H1 ratio. These results demonstrated a transient clinical improvement and support the concept of spinal cord hyperexcitability in primary RLS/WED providing new evidences for a new non-pharmacological intervention.

These studies shed light on a relatively unexplored frontier for RLS/WED non-pharmacological treatment. Despite some promising results, further multicenter researches are needed in order to offer a more powerful account of non-pharmacological treatments efficacy and to explain how they can help clinicians in treating drug resistant or intractable RLS/WED patients.

Conclusion

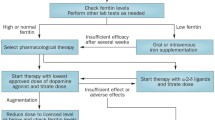

Despite considerable attention has been dedicated in recent years to understanding the best treatment choices for intractable RLS/WED, there are still no clear indications to provide guidance regarding its optimal management. A wide range of therapeutic approaches are now available for the physician, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological [Fig. 1]. However, the decision regarding the agent to use in treating severe RLS/WED varies between clinicians. Furthermore, as the severity and frequency of RLS/WED symptoms vary widely between patients, personalized treatment options are needed. Rigorous randomized studies of long-term treatment are necessary in order to define which is the best approach to relieve symptoms in this illness.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Allen RP, Picchietti DL, Garcia-Borreguero D, Ondo WG, Walters AS, Winkelman JW, et al. International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease diagnostic criteria: updated International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) consensus criteria–history, rationale, description, and significance. Sleep Med. 2014;15:860–73. This paper provides an important description and historical overview that brings to the updated diagnostic criteria for RLS/WED.

Manconi M, Ferri R, Zucconi M, Oldani A, Fantini ML, Castronovo V, et al. First night efficacy of pramipexole in restless legs syndrome and periodic leg movements. Sleep Med. 2007;8:491–7. This study demonstrates the immediate efficacy and tolerability of pramipexole in RLS/WED patients.

Mackie S, Winkelman JW. Long-term treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS): an approach to management of worsening symptoms, loss of efficacy, and augmentation. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:351–7.

Trenkwalder C, Beneš H, Grote L, García-Borreguero D, Högl B, Hopp M, et al. (2013). Prolonged release oxycodone–naloxone for treatment of severe restless legs syndrome after failure of previous treatment: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial with an open-label extension. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:1141–50. This study provides evidence for the employment of opioids in RLS/WED treatment when first-line drugs have no efficacy.

Tzonova D, Larrosa O, Calvo E, Granizo JJ, Williams AM, De la Llave Y, et al. Breakthrough symptoms during the daytime in patients with restless legs syndrome (Willis-Ekbom disease). Sleep Med. 2012;13:151–5.

García-Borreguero D, Allen R, Kohnen R, et al. Loss of response during long-term treatment of restless legs syndrome: guidelines approved by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group for use in clinical trials. Sleep Med. 2010;11(9):956–7.

Winkelman JW, Johnston L. Augmentation and tolerance with long-term pramipexole treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS). Sleep Med. 2004;5(1):9–14.

Akpinar S. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with levodopa plus benserazide. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:739.

Garcıa-Borreguero D, Kohnen R, Silber MH, et al. The long-term treatment of restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease: evidence-based guidelines and clinical consensus best practice guidance: a report from the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Sleep Med. 2013;14(7):675–84. These guidelines give an evidenced-based approach for long term-treatment of RLS/WE.

Silber MH, Becker PM, Earley C. Garcia-Borreguero D, Ondo WG, Medical Advisory Board of the Willis-Ekbom Disease Foundation. Willis-Ekbom Disease Foundation revised consensus statement on the management of restless legs syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(9):977–86.

Lisa Klingelhoefer,A Ilaria Cova,B Sheena GuptaC and Kallol Ray ChaudhuriD, A review of current treatment strategies for restless legs syndrome (Willis–Ekbom disease), Royal College of Physicians 2014

Takahashi M, Ikeda J, Tomida T, Hirata K, Hattori N, Inoue Y. Daytime symptoms of restless legs syndrome—clinical characteristics and rotigotine effectiveness. Sleep Med. 2015;16(7):871–6. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.03.006.

Högl B, Garcia-Borreguero D, Kohnen R, et al. Progressive development of augmentation during long-term treatment with levodopa in restless legs syndrome: results of a prospective multi-center study. J Neurol. 2010;257:230–7.

Tings T, Stiens G, Paulus W, Trenkwalder C, Happe S. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with subcutaneous apomorphine in a patient with short bowel syndrome. J Neurol. 2005;252(3):361–3.

Allen RP, Earley CJ. Augmentation of the restless legs syndrome with carbidopa/ levodopa. Sleep. 1996;19:205–13.

Rinaldi F, Galbiati A, Marelli S, Cusmai M, Gasperi A, Oldani A, Zucconi M, Padovani A, Ferini-Strambi L. Defining the phenotype of Restless Legs Syndrome/Willis-Ekbom Disease (RLS/WED): a clinical and polysomnographic study, J Neurol. 2016

Allen RP, Chen C, Garcia-Borreguero D, Polo O, DuBrava S, Miceli J, et al. Comparison of pregabalin with pramipexole for restless legs syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(7):621–31.

Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST general population study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(11):1286–92. To the best of our knowledge this paper is the first large-scale, multinational, population-based profile study that employs the full standard criteria for RLS/WED.

Trenkwalder C, Benesˇ H, Grote L, et al. Prolonged release oxycodone-naloxone for treatment of severe restless legs syndrome after failure of previous treatment: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial with an open-label extension. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(12):1141–50.

Silver N, Allen RP, Senerth J, Earley CJ. A 10-year, longitudinal assessment of dopamine agonists and methadone in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2011;12(5):440–4.

Ondo WG. Methadone for refractory restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2005;20(3):345–8.

Earley CJ, Connor J, Garcia-Borreguero D, et al. Altered brain iron homeostasis and dopaminergic function in restless legs syndrome (Willis-Ekbom Disease). Sleep Med. 2014;15(11):1288–301.

Hornyak M, Kaube H. Long-term treatment of a patient with severe restless legs syndrome using intrathecal morphine. Neurology. 2012;79(24):2361–2. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318278b5e7. Epub 2012 Nov 28.

Ghosh A, Basu D. Restless legs syndrome in opioid dependent patients. Indian J Psychol Med. 2014;36(1):85–7.

Trenkwalder C, Hening WA, Montagna P, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome: an evidence-based review and implications for clinical practice. Mov Disord. 2008;23(16):2267–302.

Walters AS, Wagner ML, Hening WA, et al. Successful treatment of the idiopathic restless legs syndrome in a randomized double-blind trial of oxycodone versus placebo. Sleep. 1993;16(4):327–32.

Wang J, O’Reilly B, Venkataraman R, Mysliwiec V, Mysliwiec A. Efficacy of oral iron in patients with restless legs syndrome and a low-normal ferritin: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Sleep Med. 2009;10(9):973–5.

Ondo W. Intravenous iron dextran for severe refractory restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2010;11:494–6. These are two relevant studies investigating respectively oral and intravenous iron efficacy in RLS/WED syndrome.

Auerbach M, Pappadakis J, Bahrain H, et al. Safety and efficacy of rapidly administered (one hour) one gram of low molecular weight iron dextran (INFeD) for the treatment of iron deficient anemia. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:860–2.

Allen R, Auerbach S, Bahrain H, et al. The prevalence and impact of restless legs syndrome n patients with iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:261–4.

Cho Y, Allen R, Earley C. Lower molecular weight intravenous iron dextran for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2013;14:274–7.

Schneider J, Krafft A, Manconi M, Hübner A, Baumann C, Werth E, et al. Open-label study of the efficacy and safety of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose in pregnant women with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2015;16(11):1342–7. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.08.006. Epub 2015 Aug 20.

Silber MH, Ehrenberg BL, Allen RP, et al. An algorithm for the management of restless legs syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79(7):916–22.

The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG). White paper summary of recommendations for the prevention and treatment of RLS/WED augmentation, 2015, http://irlssg.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Summary-of-recommendations-RLS-Augmentation-13Aug2015.pdf. These white paper provides new although yet unpublished guidelines for treatment and prevention of augmentation.

Mitler MM, Browman CP, Menn SJ, Gujavarty K, Timms RM. Nocturnal myoclonus: treatment efficacy of clonazepam and temazepam. Sleep. 1986;9(3):385–92.

Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. Long-term, nightly benzodiazepine treatment of injurious parasomnias and other disorders of disrupted nocturnal sleep in 170 adults. Am J Med. 1996;100:333–7.

Della Marca G, Vollono C, Mariotti P, Mazza M, Mennuni GF, Tonali P. Levetiracetam can be effective in the treatment of restless legs syndrome with periodic limb movements in sleep: report of two cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:566–7.

Aukerman MM, Aukerman D, Bayard M, Tudiver F, Thorp L, Bailey B. Exercise and restless legs syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:487–93.

Giannaki CD, Sakkas GK, Karatzaferi C, Maridaki MD, Koutedakis Y, Hadjigeorgiou GM, Stefanidis I. Combination of exercise training and dopamine agonists in dialysis patients with RLS: A randomized double-blind placebo controlled study. ASAIO journal (American Society for Artificial Internal Organs: 1992) 2015. This study suggests that exercise training plus low dose DA could represent a valid alternative to high dosage DA in order to reduce symptoms’ severity in RLS/WED.

Hornyak M, Grossmann C, Kohnen R, Schlatterer M, Richter H, Voderholzer U, et al. Cognitive behavioural group therapy to improve patients’ strategies for coping with restless legs syndrome: a proof-of-concept trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:823–5.

Lin YC, Feng Y, Zhan SQ, Li N, Ding Y, Hou Y, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of restless legs syndrome. Chin Med J. 2015;128(13):1728.

Koo YS, Kim SM, Lee C, Lee BU, Moon YJ, Cho YW, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation on primary sensorimotor area has no effect in patients with drug-naïve restless legs syndrome: a proof-of-concept clinical trial. Sleep Med. 2015;16(2):280–7. This is a well-designed and controlled study that shows the inefficacy of tDCS in reducing RLS/WED symptomatology.

Heide AC, Winkler T, Helms HJ, Nitsche MA, Trenkwalder C, Paulus W, et al. Effects of transcutaneous spinal direct current stimulation in idiopathic restless legs patients. Brain Stimul. 2014;7(5):636–42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Fabrizio Rinaldi, Andrea Galbiati, Sara Marelli, Luigi Ferini Strambi and Marco Zucconi each declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Sleep Disorders

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rinaldi, F., Galbiati, A., Marelli, S. et al. Treatment Options in Intractable Restless Legs Syndrome/Willis-Ekbom Disease (RLS/WED). Curr Treat Options Neurol 18, 7 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-015-0390-1

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-015-0390-1