Opinion statement

The accurate diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) helps identify those in need of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy. Conversely, ruling out EPI identifies those in which additional evaluation should be pursued to explain their symptoms. There are many available tests that can be used to diagnose EPI; however, the tests must be tailored to each clinical scenario. Tests that are convenient but less accurate (e.g., fecal elastase-1, qualitative fecal fat determination) are best suited for patients with a high pretest probability of EPI. In contrast, tests that are highly accurate but more cumbersome (e.g., endoscopic pancreatic function testing, 72-h fecal fat collection) are favored in patients suspected to have mild EPI or an early stage of chronic pancreatitis. Additional research is needed to identify a more convenient means of accurately diagnosing at all stages of EPI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The pancreas has both endocrine and exocrine functions. Amylase, proteases, and lipase are made and secreted into the pancreatic fluid to digest carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. EPI is defined as a relative deficiency of the endogenous pancreatic enzyme production, secretion, and action to accomplish normal digestion of nutrients. Due to the lack of significant redundancy in lipase production (compare to salivary amylase and gastric pepsin), the most clinically relevant aspect of EPI is inadequate fat digestion. This can develop at different stages of various diseases including cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, and after pancreatic surgery. For example, approximately 80 % of children with cystic fibrosis develop EPI within the first 2 years of life [1]. Conversely, 30 % of individuals with mild and 85 % with severe chronic pancreatitis will develop EPI, though this may take approximately 10–15 years after the onset of disease [2]. Early diagnosis of EPI is ideal to prevent symptoms that can impair quality of life, prevent malnutrition from nutrient malabsorption, and minimize the development of secondary complications. Herein, we discuss various clinical pearls and pitfalls in the diagnosis of EPI.

Manifestations of EPI

Clinical manifestations of EPI can range from mild to severe. In its severe form, EPI is manifest by loose stools, which are often described as oily and difficult to flush. A greasy or oily film on the toilet water is highly suggestive of fat malabsorption. Steatorrhea may be subclinical when patients restrict their dietary fat intake to avoid producing symptoms. Symptoms of mild EPI include abdominal bloating and cramping, which are easily overlooked or attributed to other causes (e.g., IBS) in the absence of a high index of clinical suspicion. EPI has been associated with fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies and weight loss, and there are emerging data demonstrating a strong association with metabolic bone disease, particularly in those with chronic pancreatitis [3, 4]. In addition to these nutritional consequences, patients with EPI may suffer from an overall impaired quality of life, which can be improved with pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) [5].

Diagnosis of EPI

Diagnosing EPI is of great clinical importance, and ideally, this would be done early, prior to the development of complications. There are a variety of testing options for EPI, which vary based on invasiveness, cost, and diagnostic accuracy. Physiologically, the tests are categorized as direct or indirect pancreas function tests (PFTs) [6]. Direct PFTs involve providing hormonal pancreatic stimulation (IV secretin, cholecystokinin, or a combination), then measuring the bicarbonate and enzyme concentration and/or output of resultant pancreatic fluid secretions. Although these tests are invasive, they are highly accurate, and are useful for diagnosing those with mild or severe EPI. Indirect PFTs are noninvasive tests that provide a measure of exocrine function without direct hormonal stimulation. Indirect PFTs detect moderate to severe EPI but are less accurate in patients with mild EPI. Therefore, the clinician is frequently faced with the dilemma of needing to use more invasive tests to evaluate for patients who are less likely to have EPI.

Indications for Exocrine Pancreatic Function Testing

There are three primary indications to offer pancreatic function testing: (i) diagnosis of EPI in those with previously diagnosed pancreatic disease, (ii) evaluation of suspected early pancreatic disease, and (iii) monitoring of therapy for EPI. One of the current challenges to accurately diagnosing EPI is the absence of well-defined high risk populations [7]. The risk of EPI is best characterized in cystic fibrosis, where the prevalence and severity of EPI is high. Other high-risk populations for EPI have been proposed, but not well-characterized, including the following: pancreatic cancer, chronic pancreatitis with main pancreatic duct dilation, severe acute pancreatitis, and post-pancreatectomy [8].

An important clinical scenario for the use of PFTs is in those with suspected early pancreatic disease. For example, in patients with clinical suspicion of chronic pancreatitis and normal or equivocal imaging tests, evidence of EPI might help implicate this as the underlying disease. In these patients with subtle or early disease, invasive, direct PFTs are typically recommended, due to improved sensitivity in mild EPI [9•]. On the other hand, indirect PFTs are generally adequate for patients with more overt morphological abnormalities (e.g., calcifications and/or main pancreatic duct dilation).

Direct Pancreas Function Testing

Secretin PFT measures bicarbonate concentration as an assessment of the duct-cell function, while CCK PFT measures enzyme content (e.g., lipase, trypsin) as an assessment of acinar-cell function. Fluid is collected through either an enteric tube or directly through an upper endoscope. Historically, direct PFTs were accomplished by placement of a fluoroscopically placed oroenteric tube, called a Dreiling tube. This dual lumen tube permitted continuous aspiration of gastric luminal contents (to avoid contaminating subsequent collections) and aspiration of intestinal contents. For the CCK-stimulated PFT, two double lumen tubes were used. The additional tube was used to infuse an inert marker (e.g., PEG, mannitol) to more accurately calculate the volume of fluid produced. Measurement of the concentration of the inert marker in the duodenal fluid allowed an adjustment for “missed” fluid not collected from the distal port. Although direct PFT using an enteric tube was felt to be highly accurate, it was somewhat difficult for patients to tolerate and often required prolonged fluoroscopy time to facilitate and maintain proper tube location. Because of these challenges, there has been a shift to the use of endoscopic pancreatic function testing (ePFT) over the last decade.

Several variations of direct PFTs using endoscopy have been described including the use of secretin and/or CCK [10–15]. Rather than using an enteric tube, duodenal lumen contents are aspirated through the accessory channel of the endoscope. For the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, the measurement of peak bicarbonate concentration appears to have superior discrimination compared to peak lipase and amylase concentrations [11•]. Although measurement of bicarbonate concentration is most immediately a measure of pancreatic duct-cell function rather than acinar-cell function (i.e., exocrine function), previous studies have demonstrated a correlation between the peak bicarbonate and lipase concentrations [16]. A peak bicarbonate concentration <80 meq/L over 60 min following secretin stimulation is abnormal (or peak <75 meq/L at 45 min) [14]. Even though ePFTs do not require specialized endoscopic tools, use is limited to a small number of academic institutions. The influence of deep levels of sedation (often required in patients using narcotic analgesia for management of chronic abdominal pain), cigarette smoking, and other potential confounders on bicarbonate results remains to be explored [17].

Indirect Pancreas Function Tests

Quantitative Fecal Fat Analysis/Coefficient of Fat Absorption

Among indirect testing methods, a 72 stool collection to determine the coefficient of fat absorption (CFA) is considered the gold standard to diagnose fat malabsorption (and EPI) by many experts [18, 19]. The test involves consumption of a high-fat diet (100 g/day) for at least 5 days with stool collection during the terminal 72 h. If previously started empirically, PERT should be held during the testing period to most accurately quantitate the amount of fat malabsorption. The dietary fat intake is carefully recorded, and is factored into the CFA calculation, as follows:CFA (%) = 100 × [(mean daily fat intake – mean daily stool fat) / mean daily fat intake].

A CFA of <0.93 (which corresponds to >7 g of stool fat per 24 h period while on a 100 g fat diet) is considered abnormal. In the research setting, many investigators perform this test while patients are admitted to a hospital unit and given a supervised diet, which typically includes food dyes to more precisely determine when to begin the stool collection. However, whether or not this provides a meaningful improvement in the test accuracy (compared to performing the test at home) is uncertain. There are several practical issues to consider when using the CFA to diagnose EPI. Most importantly, an abnormal CFA is not specific for EPI, and merely reflects fat malabsorption; therefore, abnormal values can be observed in other gastrointestinal diseases including celiac disease, short gut syndrome, and bacterial overgrowth. Second, many patients with EPI are reluctant to consume the high fat diet, because they have previously recognized fatty foods exacerbate their symptoms. Since the equation for CFA takes daily intake into consideration, the inability to consume the entire 100 g of dietary fat per day is not a contraindication. Although many patients initially find the testing methodology distasteful, with appropriate counseling regarding the value of the test result, most are willing and able to successfully complete the test.

13C-Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test

The 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test (MTBT) is an indirect PFT that measures the intraluminal lipolytic activity, which reflects exocrine pancreatic function. The MTBT has been used for decades and is based on the principle that pancreatic lipase is necessary for digestion and absorption of triglycerides [20, 21]. The test involves ingestion of a standardized meal (including triglycerides with radiolabelled carbon tracers). The triglycerides are hydrolyzed by pancreatic lipase releasing 13C, which is absorbed and transported to the liver. In the liver, additional lipolysis and beta-oxidation occur resulting in the formation of 13CO2. These molecules are ultimately exhaled by the lungs and can be measured. Breath samples are collected every 15 min for a total of 6 h, and the amount of exhaled 13C is compared to the original administered dose. A decreased recovery of 13CO2 correlates with decreased pancreatic lipase secretion.

Studies evaluating the test performance of the MTBT for diagnosing EPI have been small (<100 subjects) and heterogeneous (e.g., patient populations, definition of EPI, variations in MTBT protocol, etc.); so, pooling the data is not valid. Nevertheless, the MTBT does appear to be a useful means for diagnosing fat maldigestion from EPI. For example, Dominguez et al. studied 29 patients with chronic pancreatitis and demonstrated a significant correlation with the CFA (calculated from 72 h stool collections) [22]. Similarly, Keller and colleagues studied a group of 10 healthy volunteers and 9 patients with suspected recurrent acute or chronic pancreatitis, using MTBT compared to the secretin-stimulated duodenal lipase output [23]. The sensitivity and specificity of MTBT were excellent (100 and 92 %, respectively) for diagnosing EPI in patients with suspected pancreatic disease (after alternative causes of fat malabsorption were excluded).

Over the last decade, the test meal has been standardized, and the normal 6 h cumulative 13C recovery rate is approximately 27–29 % [24, 25]. Although age and gender do not influence the test results, even moderate exercise can increase or decrease the results [26, 27]. Therefore, patients are asked to remain seated during the testing period in an effort to reduce variability in endogenous carbon dioxide production. Although this test is appealing as a non-invasive test, it requires a substantial time investment from patients (6–8 h) in which they can only have limited activity. A recent study suggested the diagnostic accuracy remains good (sensitivity 88 % and specificity 94 %) when an abbreviated 4 h test was performed, but this requires further validation [24]. The largest problem with the MTBT is that the radiolabelled tracers required for the study are not available worldwide. Thus, this test is primarily limited to specialized centers in Europe.

Fecal Elastase-1

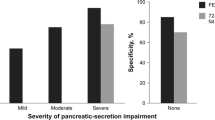

Fecal elastase-1 (FE-1) is a simple diagnostic test that can be performed on a random stool sample, obviating the need for a cumbersome stool collection over multiple days. Pancreatic elastase is an enzyme that is resistant to degradation as it passes through the intestinal tract and can readily be measured in the stool (in higher concentrations than pancreatic juice) [28]. The FE-1 test is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assay, which uses antibodies against human pancreatic elastase. Early studies demonstrated that FE-1 values were strongly correlated with duodenal outputs of pancreatic enzymes obtained during direct PFTs [29, 30]. A FE-1 value <100 mcg/g of stool is indicative of severe EPI, while levels from 100–200 are described as suggestive of mild EPI in the correct clinical context. The accuracy of FE-1 varies depending on the severity of steatorrhea and stage of pancreatic disease. Unfortunately, the test is less accurate in mild stages of disease, making it less useful as a true screening test.

One common pitfall encountered is the analysis of a liquid stool specimen. Since a concentration is measured, liquid stools will frequently lead to falsely low results due to dilution. This can be overcome by requesting a more formed specimen from the patient, by concentrating the stool samples through lyophilization, or centrifugation [31]. Although a low FE-1 is conceptually a more specific indicator of pancreatic disease in comparison to a decreased fecal fat, it should be recognized that decreased FE-1 values have been reported in a notable proportion of individuals with diabetes mellitus (15–40 %), celiac disease (30 %), and irritable bowel syndrome (5 %) [32]. The cause of abnormal FE-1 levels in these patient populations is not fully understood, but it is doubtful to be a direct reflection of EPI in all circumstances. Importantly, steatorrhea (>7 g stool fat/day) is typically only observed at extremely low FE-1 levels [33•]. Lastly, FE-1 values are not affected by PERT, so enzymes do not need to be discontinued prior to testing (if started empirically) and this is not an effective means of monitoring response to therapy.

Fecal Chymotrypsin

Fecal chymotrypsin is a test that is conceptually similar to the FE-1, and measures an alternative pancreatic protease excreted into the gut lumen. Similar to FE-1, chymotrypsin passes through the gut without significant degradation [28]. The level is influenced by PERT (which increases the value), so pancreatic enzymes should be held for approximately 3 days prior to testing if the clinician intends to establish a primary diagnosis of EPI [34]. A level less than 3 U/g of stool is considered diagnostic of EPI [34].

Similar to other indirect PFTs, fecal chymotrypsin is less sensitive for detecting mild steatorrhea [29]. For example, in a direct comparison in 123 patients with cystic fibrosis, it was demonstrated that both FE-1 and fecal chymotrypsin detected severe steatorrhea (defined in this study as stool fat content of >15 g/day); however, the sensitivity for mild steatorrhea was lower with chymotrypsin compared to FE-1 (41.0 vs. 69.2 %, respectively) [35]. The sensitivity of fecal chymotrypsin to detect EPI (diagnosed using either direct PFT or fecal fat analysis) is inferior to FE-1 in head to head comparisons, so it is no longer utilized in clinical practice [35].

Qualitative fecal Fat Analysis—Sudan Stain

Performing a semi-quantitative fat analysis on a random stool sample also obviates the need for a 72 h stool collection. However, this test less accurately quantitates fat malabsorption and is subject to interpretive error. Patients are typically asked to hold PERT (if previously started) and to consume a high fat diet preceding the stool collection. The observation of >6 fat droplets per high power field is indicative of fat malabsorption. This threshold may not be reached until there is >20 g stool fat/day; so, this analysis is insensitive for mild disease [9].

Monitoring For Treatment Response

Following initiation of PERT, it is important to monitor the effectiveness of therapy by evaluating nutritional endpoints, including normalization of body weight and resolution of steatorrhea. Unfortunately, many patients may continue to have malnutrition despite resolution of symptoms. For example, in a series of 30 patients with chronic pancreatitis-related steatorrhea on PERT, 20/30 (66.7 %) continued to have malnutrition (indicated by a low retinol binding protein level) despite normalization of symptoms [36]. Therefore, many experts currently advocate for testing to document effectiveness of PERT in all patients.

In addition to CFA, the MTBT has been evaluated as a means to demonstrate a functional response to PERT. In one study evaluating 29 subjects with chronic pancreatitis-related steatorrhea, CFA and MTBT were performed prior to and following a 2-week course of PERT [22]. Both tests demonstrated improvement in all subjects. The CFA normalized in 18 (65.5 %) subjects, and MTBT results normalized in 15 (51.7 %) subjects. When used to determine adequacy of treatment, patients need to continue PERT leading up to the MTBT, including during ingestion of the test meal. As previously discussed, FE-1 levels are not affected by PERT, and therefore are not an appropriate means of monitoring treatment response.

Conclusion

The accurate diagnosis of EPI is necessary to guide initiation of PERT, and hopefully avoid disease-related complications. It is also clinically valuable to identify patients with suspected pancreatic disease with EPI to confirm the diagnosis and permit appropriate disease management. Unfortunately, a simple, inexpensive, non-invasive test for diagnosis of EPI does not currently exist, so physicians must tailor their use of diagnostic tests to the specific clinical scenario. For patients with symptoms suspicious for early chronic pancreatitis, a direct PFT is helpful to establish a correct diagnosis. Conversely, in patients at high risk for developing EPI, a noninvasive form of PFT is likely sufficient. In the future, additional investigations are needed to improve our ability to use noninvasive testing to accurately detect mild EPI.

Abbreviations

- CFA:

-

Coefficient of fat absorption

- EPI:

-

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

- FE-1:

-

Fecal elastase-1

- MTBT:

-

13C-mixed triglyceride breath test

- PERT:

-

Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy

- PPI:

-

Proton pump inhibitor

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Durno C, Corey M, Zielenski J, et al. Genotype and phenotype correlations in patients with cystic fibrosis and pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1857–64.

Layer P, Yamamoto H, Kalthoff L, et al. The different courses of early- and late-onset idiopathic and alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1481–7.

Tignor AS, Wu BU, Whitlock TL, et al. High prevalence of low-trauma fracture in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2680–6.

Duggan SN, Smyth ND, Murphy A, et al. High prevalence of osteoporosis in patients with chronic pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:219–28.

Czako L, Takacs T, Hegyi P, et al. Quality of life assessment after pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in chronic pancreatitis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:597–603.

Conwell DL, Wu BU. Chronic pancreatitis: making the diagnosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1088–95.

Hart PA CD. Challenges and updates in management of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Pancreas 2015.

Dominguez-Munoz JE. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency: diagnosis and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(2):12–6.

Conwell DL, Lee LS, Yadav D, et al. American pancreatic association practice guidelines in chronic pancreatitis: evidence-based report on diagnostic guidelines. Pancreas. 2014;43:1143–62. Recently published guidelines regarding the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. This article provides further details about encorporating functional and structural assessments of the pancreas to diagnose chronic pancreatitis.

Conwell DL, Zuccaro G, Morrow JB, et al. Cholecystokinin-stimulated peak lipase concentration in duodenal drainage fluid: a new pancreatic function test. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1392–7.

Law R, Lopez R, Costanzo A, et al. Endoscopic pancreatic function test using combined secretin and cholecystokinin stimulation for the evaluation of chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:764–8. A recent, large study examining endoscopic pancreatic function testing. The authors demonstrated the additon of cholecystokinin stimulation to secretin stimulation did not improve the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.

Stevens T, Conwell DL, Zuccaro G, et al. Electrolyte composition of endoscopically collected duodenal drainage fluid after synthetic porcine secretin stimulation in healthy subjects. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:351–5.

Stevens T, Conwell DL, Zuccaro Jr G, et al. A randomized crossover study of secretin-stimulated endoscopic and dreiling tube pancreatic function test methods in healthy subjects. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:351–5.

Stevens T, Conwell DL, Zuccaro Jr G, et al. The efficiency of endoscopic pancreatic function testing is optimized using duodenal aspirates at 30 and 45 minutes after intravenous secretin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:297–301.

Stevens T, Conwell DL, Zuccaro Jr G, et al. A prospective crossover study comparing secretin-stimulated endoscopic and dreiling tube pancreatic function testing in patients evaluated for chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:458–66.

Stevens T, Dumot JA, Zuccaro Jr G, et al. Evaluation of duct-cell and acinar-cell function and endosonographic abnormalities in patients with suspected chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:114–9.

Kadiyala V, Lee LS, Banks PA, et al. Cigarette smoking impairs pancreatic duct cell bicarbonate secretion. J Pancreatol. 2013;14:31–8.

Forsmark CE. Management of chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1282–91.

Pezzilli R, Andriulli A, Bassi C, et al. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in adults: a shared position statement of the Italian association for the study of the pancreas. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7930–46.

Vantrappen GR, Rutgeerts PJ, Ghoos YF, Hiele MI. Mixed triglyceride breath test: a noninvasive test of pancreatic lipase activity in the duodenum. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1126–34.

Loser C, Brauer C, Aygen S, et al. Comparative clinical evaluation of the 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test as an indirect pancreatic function test. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:327–34.

Dominguez-Munoz JE, Iglesias-Garcia J, Vilarino-Insua M, Iglesias-Rey M. 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test to assess oral enzyme substitution therapy in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:484–8.

Keller J, Bruckel S, Jahr C, Layer P. A modified (1) (3) C-mixed triglyceride breath test detects moderate pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. Pancreas. 2011;40:1201–5.

Keller J, Meier V, Wolfram KU, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of an abbreviated (13) C-mixed triglyceride breath test for measurement of pancreatic exocrine function. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2014;2:288–94.

Dominguez-Munoz JE, Iglesias-Garcia J, Castineira Alvarino M, et al. EUS elastography to predict pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:136–42.

Jonderko K, Dus Z, Szymszal M, et al. Normative values for the 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test in two age groups. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:CR255–9.

Kalivianakis M, Verkade HJ, Stellaard F, et al. The 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test in healthy adults: determinants of the 13CO2 response. Eur J Clin Investig. 1997;27:434–42.

Sziegoleit A, Krause E, Klor HU, et al. Elastase 1 and chymotrypsin B in pancreatic juice and feces. Clin Biochem. 1989;22:85–9.

Katschinski M, Schirra J, Bross A, et al. Duodenal secretion and fecal excretion of pancreatic elastase-1 in healthy humans and patients with chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1997;15:191–200.

Stein J, Jung M, Sziegoleit A, et al. Immunoreactive elastase I: clinical evaluation of a new noninvasive test of pancreatic function. Clin Chem. 1996;42:222–6.

Fischer B, Hoh S, Wehler M, et al. Faecal elastase-1: lyophilization of stool samples prevents false low results in diarrhoea. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:771–4.

Leeds JS, Oppong K, Sanders DS. The role of fecal elastase-1 in detecting exocrine pancreatic disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:405–15.

Benini L, Amodio A, Campagnola P, et al. Fecal elastase-1 is useful in the detection of steatorrhea in patients with pancreatic diseases but not after pancreatic resection. Pancreatology. 2013;13:38–42. This study compared the diagnostic performance of FE-1 and coefficient of fat absorption in patients with a variety of pancreatic disorders. In those without a history of pancreatic surgery, steatorrhea was only observed in those with an exceedingly low FE-1 level, indicating this test is not accurate as a screening test in those without pancreatic disease.

Scotta MS, Marzani MD, Maggiore G, et al. Fecal chymotrypsin: a new diagnostic test for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in children with cystic fibrosis. Clin Biochem. 1985;18:233–4.

Walkowiak J, Herzig KH, Strzykala K, et al. Fecal elastase-1 is superior to fecal chymotrypsin in the assessment of pancreatic involvement in cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e7.

Dominguez-Munoz JE, Iglesias-Garcia J. Oral pancreatic enzyme substitution therapy in chronic pancreatitis: is clinical response an appropriate marker for evaluation of therapeutic efficacy? JOP. 2010;11:158–62.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Phil A. Hart declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Darwin L. Conwell declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hart, P.A., Conwell, D.L. Diagnosis of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency. Curr Treat Options Gastro 13, 347–353 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-015-0057-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-015-0057-8