Abstract

Purpose of the review

Patients who undergo single ventricle palliation with a Fontan are at a high risk for developing arrhythmias. This review will address our understanding of pathophysiology, incidence, presentation, and type of arrhythmia, focusing on recent developments.

Recent findings

Patients with the initially described atriopulmonary connection type of Fontan have a high incidence of arrhythmias, with severe consequences. Arrhythmias are less of a problem with the two currently used surgical techniques, the lateral tunnel and the extracardiac conduit Fontan, with the extracardiac Fontan being potentially less arrhythmogenic in the long term.

Summary

There is no role for the atriopulmonary Fontan any longer. As the lateral tunnel and extracardiac conduit patients age, there will be a greater understanding of the unique complications specific to their unique anatomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Arrhythmias are arguably the most important complication in patients who undergo the Fontan operation. They are an important cause of clinical deterioration and death, whether they occur immediately after surgery or many years later [1]. The relationship between arrhythmias (electrical problems) and hemodynamics (mechanical issues) is complex and can be compared with the chicken versus egg discussion. Mechanical problems like poor ventricular function and valve regurgitation predispose the patient to arrhythmias. In turn, arrhythmias can lead to poor ventricular function, and to the development of problems like protein-losing enteropathy (PLE), and thrombus formation. Once established, the vicious cycle of arrhythmias can be hard to interrupt. Arrhythmia has been described as a strong “predictor of mortality” and “key marker of deterioration” with a 23-fold increased risk of death [1]. However, the Fontan is not one operation. At least two major modifications, namely the intracardiac lateral tunnel (ILT) and the extracardiac conduit (ECC), have been described since the original atriopulmonary connection (APC) type of Fontan, and they have had a significant impact on the incidence and severity of arrhythmias.

Incidence

The incidence of early post-operative arrhythmias after the APC Fontan is estimated to be around 10–30% [2, 3]. This is however now only of historical interest as the APC is now rarely performed. More important is the incidence of late arrhythmias in this population, with estimates of the occurrence of late bradyarrhythmias (predominantly loss of sinus rhythm with a slower junctional escape rhythm) in up to 40% of patients and late tachyarrhythmias in up to 80% [1, 4] (Table 1).

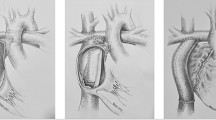

de Leval developed the total cavo-pulmonary connection (TCPC) primarily based on his observation that the APC Fontan was an inefficient circulation, with the theory that streamlining the flow of blood from the inferior vena cava (IVC) through the right atrium (RA) to the pulmonary artery (PA) could improve outcomes including reducing the incidence and severity of arrhythmias [25]. The surgical method of TCPC he described now goes by the name intracardiac lateral tunnel (ILT). His hopes of hemodynamic improvement were immediately realized with a lower incidence of arrhythmias, which were better tolerated by the patients [17, 26]. Marcelletti almost immediately went a step beyond de Leval and described the extracardiac conduit (ECC) Fontan, thus seeking to avoid the RA completely to achieve the primary aim of eliminating the potential for arrhythmias [27, 28].

The incidence of arrhythmias has significantly decreased since the adoption of the ILT and the ECC modifications of the Fontan operation. Numerous studies have shown this decreased incidence with ILT and ECC as compared with APC. Quinton et al. [1] describe a reduction in the incidence of late arrhythmia in the ILT and ECC groups down to 23%; however, the cohort data shows a sharp increase in the arrhythmia burden in the APC group at the 20–25-year mark post-Fontan, and Quinton notes that the ILT and ECC will need to be followed further to evaluate for a similar increase in arrhythmia as these cohorts age. Pundi et al. [23••] and Dennis et al. [4] both similarly describe a decrease in the incidence of late arrhythmia by about 70% in the ILT and ECC groups as compared with the APC group; however, they also note that these findings may be an underestimate given the shorter follow-up duration in these cohorts.

Early bradyarrhythmias are estimated to occur in 4–22% of patients after the ILT and in 0–27% after the ECC (Table 1). Studies that directly compare one cohort to the other have described differing results with some showing an increased tendency for early bradyarrhythmias in the ILT group [8, 11, 18], and others showing a higher tendency in the ECC group [7, 17]. Late occurring bradyarrhythmias are estimated at around 10–77% after the ILT and 0–29% after the ECC (Table 1).

Early tachyarrhythmias have been described to occur in 2–38% of patients after ILT and 0–11% after the ECC [7, 8, 17, 18, 23]. Most of the attention has been on late tachyarrhythmias as this is a key determinant of long-term outcome [22, 29]. Late tachyarrhythmias have been shown to occur in 4–33% of the ILT group and 0–9% of the ECC group [4,5,6,7,8, 15, 17, 18, 20, 23]. Again, direct comparison of these two surgeries has been complicated by the fact that the ILT procedure was described earlier and therefore the ILT cohort tends to be older and undergone longer follow-up, and so the current data may be underestimating the incidence of the late arrhythmias in the ECC cohort. Larger scale studies [17, 19, 20] do show a trend for a lower incidence of arrhythmias in the ECC group, and is a difference from smaller scale studies [7, 10, 18], which have shown a less significant reduction; however, further follow-up of the ECC cohort remains necessary to fully evaluate the efficacy of this surgery on reducing the incidence of arrhythmia.

Etiology and pathophysiology

Bradyarrhythmias

Bradyarrhythmias, especially sinus node dysfunction, is an important post-operative problem. Extensive dissection in the region of the sinus node and its arterial supply either at the Fontan or at the earlier-stage operations (particularly the Glenn operation) can result both in immediate (early) or late severe sinus node dysfunction [7, 11]. Heart block due to atrioventricular (AV) node dysfunction is less common, although the patients’ underlying anatomy may be a factor. For example, patients with single ventricles associated with heterotaxy syndromes and with L-looped ventricles have been well described to have a predisposition to the development of de novo heart block [9].

Transient sinus node dysfunction with the need for temporary pacing can often be seen in the post-operative period and can resolve spontaneously without the need for a permanent pacemaker [17, 19]. Early atrial arrhythmia has also been shown to be associated with late tachy and bradyarrhythmias, likely due to an additive effect of disruption to nodal tissues with progressive atrial dilation [23••].

Late bradyarrhythmia

Sinus node dysfunction and less commonly AV block are common longer term problems in Fontan patients. Bradyarrhythmias are associated with decreased ventricular function and found to have freedom from decreased ventricular function at 15 years of only 46% [20••]. There is no significant difference found between the ILT and ECC patients in regard to incidence of late bradyarrhthmia [17, 18]. Sinus node dysfunction remains a major cause of pacemaker placement in this population and has been reported to occur in 6–12% of patients [4, 15, 17, 19, 20].

Tachyarrhythmias

Tachyarrhythmias, especially supraventricular tachycardias (SVT) in the APC, are thought to be primarily due to the extensive suture lines in the atrium, which set up the substrate for atrial reentry tachycardia. The obligatory increase in right atrial (RA) pressure predisposes the APC Fontan patients to develop severe RA dilation, which further stretches the surgical scars, creating the toxic combination of factors that result in a high incidence of arrhythmias [4, 22, 29, 30].

Of all the arrhythmias that occur, the most important from a prognostic viewpoint is the issue of late occurring tachyarrhythmias. The most common tachyarrhythmia seen in younger patients is a reentry arrhythmia around scars (called IART or intra-atrial reentry tachycardia), although cavo-tricuspid (or typical) atrial flutter and ectopic (or focal) atrial tachycardia (EAT) are also often seen, especially in the longer term [1, 15, 21]. As Fontan patients become older, a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation is noted and this will likely prove to be the major electrical problem as these patients survive to old age. Indeed “brady begets tachy” is a familiar electrophysiological dictum and an estimated 21% of Fontan patients develop both brady and tachyarrhythmias [20••]. Tachyarrhythmias, by the phenomenon of overdrive suppression, can lead to “weakening” of the intrinsic pacemakers such that when the tachyarrhythmia terminates (sometimes spontaneously, sometimes by medical intervention), there is severe bradycardia and potentially even asystole. This is an important aspect to be borne in mind when treating these patients.

Numerous studies have shown that atrial tachyarrhythmias are common among Fontan patients with prevalence of up to 60% at 20 years after initial Fontan surgery [4, 21,22,23], with one report describing a 100% incidence in the APC Fontan patients at 26-year follow-up [1]. In all Fontan patients who develop an atrial tachycardia, IART and EAT are the most common forms occurring in 40–60% [31]. Atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation have an estimated incidence of 21–66% [20, 21, 23], with some reports citing an even higher incidence of up to 83% in APC Fontan patients [22••]. Atrial fibrillation has an incidence of 2–40% [4, 20,21,22]. Ventricular tachycardias are the least frequent of the tachyarrhythmias in the Fontan population with a cited incidence of 3–10% [23, 32]. In patients with an APC Fontan presenting for an atrial arrhythmia ablation, the most common arrhythmia induced was IART (93%) with atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia and atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia occurring in ~ 4% [33]. As the ILT and ECC cohorts age, the incidence of the subtypes of arrhythmias will be better elucidated and the efficacy of these surgical modifications can be better compared with the APC.

Clinical presentation

The presentation of arrhythmias in the Fontan population can vary from the subtle (vague or mild symptoms of fatigue and respiratory distress) to the catastrophic (syncope or rarely, cardiac arrest). Arrhythmias, which can cause stasis of blood, combined with the presence of patch material make them a higher risk for acute thromboembolic events [34,35,36]. While underlying structural problems such as poor ventricular function, and valve regurgitation predispose to arrhythmias, in turn, arrhythmias often lead to Fontan failure and deterioration, with 40% of patients developing decreased ventricular function following the first onset of an arrhythmia [1, 20]. Atrial arrhythmias have been associated with a sixfold increase in transplantation and death [29]. Sinus node dysfunction has also been implicated in the development of plastic bronchitis and protein-losing enteropathy in Fontan patients [37••]. The decrease in ventricular filling time and dyssynchronous contractions is poorly tolerated in patients with single ventricles and any imaging or clinical signs of poor function should raise a high suspicion for arrhythmia in this population given the wide range of clinical presentation [34, 37, 38]. Given the significant morbidity and mortality associated with arrhythmias, a significant amount of attention has been directed in routinely evaluating the rhythm in these patients and this will likely continue in the future care of these patients.

Sudden death

Arrhythmias with severe cardiac compromise and even sudden cardiac death are also a major problem in this population [39,40,41]. Sudden death alone has been noted to have an incidence of 5–10% and occur at an average age of 20.5 years. An underlying arrhythmia was found in 65% of Fontan patients who developed sudden death. Additionally, risk factors for sudden death included AV valve replacement at the time of Fontan operation and post-bypass Fontan circuit pressure greater than 20 mmHg. Pre-operative presence of sinus rhythm has been found to be a protective factor [23••]. Further studies into the mechanism of sudden death in this population are needed with particular attention to identifying which subgroup of patients would benefit from ICD placement.

Summary

The development of any bradyarrhythmia or tachyarrhythmia is an independent predictor of a poor clinical outcome. A study on long-term outcomes after first-onset arrhythmia in Fontan patients showed that the 15-year survival following the development of any arrhythmias was only 70% and freedom from Fontan failure was only 44% [20••]. Tachyarrhythmias are especially associated with increased Fontan failure, sudden cardiac death, and mortality [1, 4, 20, 23, 32]. In APC patients, 83% of those with a dilated atrium also had a documented arrhythmia, and this was associated with increased risk of heart failure and death [22••]. This phenomenon was a concern posed by Dr. Francis Fontan during his initial description of the procedure in 1971 and has instigated the development of modifications to the initial procedure [29]. Thus far, the ILT and more recently the ECC have shown some promising results in regard to the incidence of arrhythmias [18, 19]. A systemic review and meta-analysis by Li et al. [42••] in 2017 showed that ECC Fontan patients have a twofold lower risk of late arrhythmias compared with ILT patients. This needs to be taken in the context of changes in a surgical era in addition to the other factors impacting the incidence of late atrial tachycardias including age at the time of Fontan surgery (irrespective of Fontan type) [1], heterotaxy or atrial isomerism, and presence of ventricular-dependent coronary circulation [19,20,21, 24, 43]. Dennis et al. [4] describes that for all Fontan types prior to age 16, only 15% had experienced arrhythmic events, which is consistent with the arrhythmias being mostly a burden as these patients age into adulthood. Further studies will continue to inform the true impact of surgical techniques and other factors in regard to the incidence of arrhythmias and their impact in this vulnerable population.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Quinton E, Nightingale P, Hudsmith L, Thorne S, Marshall H, Clift P, et al. Prevalence of atrial tachyarrhythmia in adults after Fontan operation. Heart. 2015;101:1672–7.

Gewillig M, Wyse R, de Leval M, Deanfield J. Early and late arrhythmias after the Fontan operation: predisposing factors and clinical consequences. Br Heart J. 1992;67:72–9.

Peters N, Somerville J. Arrhythmias after the Fontan procedure. Br Heart J. 1992;68:199–204.

Dennis M, Zannino D, du Plessis K, Bullock A, Disney P, Radford D, et al. Clinical outcomes in adolescent and adults after the Fontan procedure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(9):1009–17.

• Gelatt M, Hamilton R, McCrindle B, Gow R, Williams W, Trusler G, et al. Risk factors for atrial tachyarrhythmias after the Fontan operation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:1735–41 A study of a cohort of 270 patients at the Hospital for Sick Children focusing on the incidence and risk factors for atrial tachyarrhythmias. The authors note that the overall incidence of arrhythmia was 20% and noted to be higher in patients with more extensive atrial surgery or manipulation which occurred more commonly in the atriopulmonary subtype.

Azakie A, McCrindle B, Van Arsdell G, Benson L, Coles J, Hamilton R, et al. Extracardiac conduit versus lateral tunnel cavopulmonary connections at a single institution: impact on outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:1219–28.

Kumar S, Rubinstein C, Simsic J, Taylor A, Saul P, Bradley S. Lateral tunnel versus extracardiac conduit Fontan procedure: a concurrent comparison. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1389–97.

Nurnberg J, Ovroutski S, Alexi-Meskishvili V, Ewert P, Hetzer R, Lange P, et al. New onset arrhythmias after the extracardiac conduit Fontan operation compared with the intraatrial lateral tunnel procedure: early and midterm results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1979–88.

Giannico S, Hammad F, Amodeo A, Michielon G, Drago F, Turchetta A, et al. Clinical outcome of 193 extracardiac Fontan patients: the first 15 years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2065–73.

Fiore A, Turrentine M, Rodefeld M, Vijay P, Schwartz T, Virgo K, et al. Fontan operation: a comparison of lateral tunnel with extracardiac conduit. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:622–30.

Lee J, Keak J, Min S, Kim W, Kim Y, et al. Comparison of lateral tunnel and extracardiac conduit Fontan procedure. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:328–30.

Nakano T, Kado H, Tachibana T, Hinokiyama K, Shiose A, Kajimoto M, et al. Excellent midterm outcome of extracardiac conduit total cavopulmonary connection: results of 126 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1619–26.

Ocello S, Salviato N, Marceletti C. Results of 100 consecutive extracardiac conduit Fontan operations. Pediatr Cardiol. 2007;28:433–7.

Kim S, Kim W, Lim H, Lee J. Outcome of 200 patients after an extracardiac Fontan procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:108–16.

•• Stephenson E, Lu M, Berul C, Etheridge S, Idriss S, Margossian R, et al. Arrhythmias in a contemporary Fontan cohort. Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:890–6 A large multicenter cohort of 520 patients using the Pediatric Heart Network data, evaluating the prevalence of tachyarrhythmia and factors that affect the timing of arrhythmia development. Overall prevalence was 7.2% and patients with an atriopulmonary subtype of Fontan were at an increased risk of developing a tachyarrhythmia; however, the follow-up time with this subtype of Fontan was longer as it was an older technique.

Miyazaki A, Sakaguchi H, Ohuchi H, Yamada O, Kitano M, Yazaki S, et al. The clinical course and incidence of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias after extra-cardiac conduit Fontan procedure in relation to an atrial situs. Circ J. 2011;75:413–20.

•• Balaji S, Daga A, Bradley DJ, Etheridge SP, Law IH, Batra AS, et al. An international multicenter study comparing arrhythmia prevalence between the intracardiac lateral tunnel and the extracardiac conduit type of Fontan operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148(2):576–81. A large multicenter study of 1271 patients comparing the intracardiac lateral tunnel and extracardiac conduit type of Fontan with reference to early and late clinical brady and tachyarrhythmia. Bradycardia defined as need for pacing. While on face of it there was a higher incidence of late tachyarrhythmias in the ILT group, the time based analysis (Kaplan-Meier curve) showed no difference.

Lasa J, Glatz A, Daga A, Shah M. Prevalence of arrhythmias late after the Fontan operation. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1184.

d’Udekem Y, Iyengar A, Galati J, Forsdick V, Weintraub R, Wheaton G, et al. Redefining expectations of long-term survival after the Fontan procedure. Circulation. 2014;130(suppl 1):S32–8.

•• Carins T, Shi W, Iyengar A, Nisbet A, Forsdick V, Zannino D, et al. Long-term outcomes after first-onset arrhythmia in Fontan physiology. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:1355–63 A retrospective analysis of a large cohort of 1034 patients from the Australian and New Zealand Fontan Registry. Authors describe predictors of developing arrhythmias to aid early detection and additionally demonstrate the prevalence of adverse long-term outcomes associated following the onset of an arrhythmia. Authors note that survival following the onset of arrhythmias was surprisingly good with 67% post-tachyarrhythmia and 84% post-bradyarrhythmia; however, there was a significant burden of Fontan failure within 10 years of the onset arrhythmias.

Egbe A, Connolly H, Khan A, Niaz T, Said S, Dearani J, et al. Outcomes in adult Fontan patients with atrial tachyarrhythmias. Am Heart J. 2017;186:12–20.

•• Poh C, Zannino D, Weintraub R, Winlaw D, Grigg L, Cordina R, et al. Three decades later: the fate of the population of patients who underwent the atriopulmonary Fontan procedure. Int J Cardiol. 2017;231(1):99–104 A retrospective analysis of 215 patients in the Australia and New Zealand Fontan Registry who had undergone the Atriopulmonary Fontan surgery and evaluating their outcome up to 40 years following their procedure. Found that arrhythmias are a significant burden with 80% of patients having an arrhythmia by 28 years post-procedure. Atrial arrhythmias also increased the risk of Fontan failure, transplantation and death.

•• Pundi K, Pundi K, Johnson J, Dearani J, Li Z, et al. Sudden cardiac death and late arrhythmias after the Fontan operation. Congenit Heart Dis. 2017;12(1):17–23 A large singl- center Mayo clinic study of 996 patients showed that freedom from arrhythmia was 24% at 30 years after the Fontan.

Marathe SP, Zannino D, Cao JY, et al. Heterotaxy is not a risk factor for adverse long-term outcomes after Fontan completion [published online ahead of print, 2019 Dec 28]. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;S0003–4975(19):31974–5.

de Leval M, Kilner P, Gewillig M, Bull C. Total cavopulmonary connection: A logical alternative to atriopulmonary connection of complex Fontan operations. Experimental studies and early clinical experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1988;96:682–95.

Cecchin F, Johnsrude C, Perry J, Friedman R. Effect of age and surgical technique on symptomatic arrhythmias after the Fontan procedure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;76:386–91.

de Leval M. The Fontan circulation: what have we learned? What to expect? Pediatr Cardiol. 1998;19:316–20.

Marcelletti C, Corno A, Giannico S, Marino B. Inferior vena cava-pulmonary artery extracardiac conduit. A new form of right heat bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990;100:228–32.

Backer C, Mavroudis C. 149 Fontan conversions. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2019;15(2):105–10.

Rijnberg F, Blom N, Sojak V, Bruggemans E, Kuipers I, Rammeloo L, et al. A 45-year experience with the Fontan procedure: tachyarrhythmia, an important sign of adverse outcome. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2019;29:461–8.

Ohuchi H. Adult patients with Fontan circulation: What we know and how to manage adults with Fontan circulation? J Cardiol. 2016;63(3):181–9.

Pundi K, Johnson J, Dearani J, Pundi K, Li Z, Hinck C, et al. 40-year follow-up after the Fontan operation: long-term outcomes of 1052 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(15):1700–10.

Moore BM, Anderson R, Nisbet AM, Kalla M, du Plessis K, d’Udekem Y, et al. Ablation of atrial arrhythmias after the atriopulmonary Fontan procedure: mechanisms of arrhythmia and outcomes. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;(10):1338–46.

Deal B, Mavroudis C, Backer C. Arrhythmia management in the Fontan patient. Pediatr Cardiol. 2007;28:448–56.

•• Rychik J, Atz A, Celermajer D, Deal B, Gatzoulis M, Gewillig M, et al. Evaluation and management of the child and adult with Fontan circulation: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140(6):234–84 This manuscript is released by the American Heart Association as a review of the current literature regarding the physiological challenges and management considerations for children and adults with the Fontan circulation, along with a consideration of the gaps in the current knowledge and guide for future research.

Stout K, Daniels C, Aboulhosn J, Bozkurt B, Broberg C, Colman J, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:698–800.

•• Khairy P, Van Hare GF, Balaji S, Berul CI, Cecchin F, Cohen MI, et al. PACES/HRS Expert Consensus Statement on the recognition and management of arrhythmias in adult congenital heart disease: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), and the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ISACHD). Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(10):e102–65 A thorough review released jointly by the Pediatric and Adult Congenital Electrophysiologic Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) regarding the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of arrhythmias in adults with congenital heart disease.

• Barber B, Batra A, Burch G, Shen I, Ungerleider R, Brown J, et al. Acute hemodynamic effects of pacing in patients with Fontan physiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1937–42 A prospective study to evaluate the hemodynamic effects of pacing in Fontan patients. The authors note that compared with atrial or dual chamber pacing, ventricular pacing resulted in lower cardiac output, elevated left atrial pressure, elevated pulmonary arterial pressure, and decreased mean arterial pressure.

Kotani Y, Chetan D, Zhu J, Saedi A, Zhao L, Mertens L, et al. Fontan failure and death in contemporary Fontan circulation: analysis from the last two decades. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105:1240–7.

Kverneland L, Kramer P, Ovroutski S. Five decades of the Fontan operation: a systematic review of international reports on outcomes after univentricular palliation. Congenit Heart Dis. 2018;13:181–93.

Poh C, Hornung T, Celermajer D, Radford D, Justo R, Andrews D, et al. Modes of late mortality in patients with a Fontan circulation. Heart. 2020;0:1–5.

•• Li D, Hirata Y, Ono M, An Q. Arrhythmia after Fontan operation with intraatrial lateral tunnel versus extra-cardiac conduit: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017;38:873–80 A systematic review and meta-analysis of the published studies comparing the intralateral tunnel and extracardiac Fontan operations in regard to incidence of early and late post-operative arrhythmias and placement of permanent pacemakers. The authors note that their meta-analysis shows no significant difference in regard to early arrhythmias or pacemaker placement. However, they do note an increased incidence of late arrhythmias in the ILT group, with the caveat that the extracardiac subtype of Fontan is the newer surgical technique with a relatively younger cohort and therefore the significant difference noted in the late arrhythmia incidence could change with time.

Elias P, Poh C, du Plessis K, Zannino D, Rice K, Radford D, et al. Long-term outcomes of single-ventricle palliation for pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum: Fontan survivors remain at risk of late myocardial ischaemia and death. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53:1230–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Mayme Marshall, Mohammad Alnoor, and Seshadri Balaji declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alnoor, M., Marshall, M. & Balaji, S. Current Treatment Options of Fontan Arrhythmias: Etiology, Incidence, and Diagnosis. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 22, 53 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-020-00849-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-020-00849-3