Abstract

Partial nephrectomy has become an accepted treatment of cT1 renal masses as it provides improved long-term renal function compared to radical nephrectomy (Campbell et al. J Urol. 182:1271–9, 2009). Hilar clamping is utilized to help reduce bleeding and improve visibility during tumor resection. However, concern over risk of kidney injury with hilar clamping has led to new techniques to reduce length of warm ischemia time (WIT) during partial nephrectomy. These techniques have progressed over the years starting with early hilar unclamping, controlled hypotension during tumor resection, selective arterial clamping, minimal margin techniques, and off-clamp procedures. Selective arterial clamping has progressed significantly over the years. The main question is what are the exact short- and long-term renal effects from increasing clamp time. Moreover, does it make sense to perform these more time-consuming or more complex procedures if there is no long-term preservation of kidney function? More recent studies have shown no difference in renal function 6 months from surgery when selective arterial clamping or even hilar clamping is employed, although there is short-term improved decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) with selective clamping and off-clamp techniques (Komninos et al. BJU Int. 115:921-8, 2015; Shah et al. 117:293-9, 2015; Kallingal et al. BJU Int. doi:10.1111/bju.13192, 2015). This paper reviews the progression of total hilar clamping to selective arterial clamping (SAC) and the possible difference its use makes on long-term renal function. SAC may be attempted based on surgeon’s decision-making, but may be best used for more complex, larger, more central or hilar tumors and in patients who have renal insufficiency at baseline or a solitary kidney.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Current guidelines recommend partial nephrectomy over radical nephrectomy for the treatment of cT1 renal masses, showing equivalent oncologic outcomes [1]. This has been proven for both T1a and T1b kidney tumors [2, 3]. Partial nephrectomy has also been shown to improve long-term renal function compared to radical nephrectomy [4]. Laparoscopic and robotic partial nephrectomies have been shown to be equivalent if not advantageous to open partial nephrectomy [5]. Hilar vessel clamping had been standard during partial nephrectomy in order to improve visibility and reduce operative blood loss. Ischemia during hilar clamping in nephron-sparing surgery causes renal damage secondary to vasoconstriction, obstruction of vessels from sloughing epithelial cells, and reperfusion injury [6, 7]. In open surgery, cooling of the kidney was used to reduce the risk of ischemic injury. However, laparoscopic and robotic approaches to cooling have been technically challenging. Warm ischemia time (WIT) along with other variables has been shown to have an effect on chronic renal damage. Renal function can be roughly assessed with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) or serum creatinine. Typically, WIT < 25 min is recommended to reduce the risk of kidney damage; however, there exists much controversy over the exact detriment of WIT on overall kidney function [8]. In addition, the relative effect of WIT compared to preoperative renal function and the amount of renal parenchyma preserved is controversial [9].

This paper summarizes the progression of minimally invasive partial nephrectomy techniques specifically selective arterial clamping (SAC) and the attempt to reduce warm ischemia time. Initially, early unclamping of the hilar vessels was described in 2008. Subsequently, microvascular dissection with selective arterial clamping was suggested. This technique was first combined with controlled hypotension at time of resection but lost favor secondary to associated risks. This technique was also first implemented with peripheral tumors, but over time was focused to more complex lesions such as hilar, central, and endophytic tumors. Selective arterial clamping, complete hilar clamping, and off-clamp techniques began to be utilized according to surgeon experience and preference. Other modalities have also been developed to aid in these procedures including Doppler ultrasound, 3D CT urogram, near-infrared fluorescence, and 3D image overlay. The goal of this paper is to review the evolution of various selective clamping techniques and assess the effectiveness of these in regards to long-term kidney function.

Early Techniques

An early attempt to reduce WIT was described by Nguyen et al. via early unclamping of the renal hilum. The hilum was unclamped just subsequent to placement of the initial central running renorrhaphy suture. Subsequent sutures were placed in a vascularized kidney. Published in 2008, a review of 100 consecutive nonrandomized patients underwent standard lap partial nephrectomy (50 patients) versus early unclamping (50 patients). The early unclamping group showed a statistically significant decreased warm ischemia time of median 13.9 versus 31.1 min. There was a significant improvement in the early unclamping group in calculated eGFR from pre- to postoperative values (17.6 ml/min/1.73 m^2 in control versus −11.3 ml/min/1.73 m^2 in the study group). Importantly, the length of follow-up in the early unclamping group was statistically shorter (117 days in control vs. 40 days for study group) [10].

Eisenberg and Gill et al. first described a “zero ischemia” partial nephrectomy in 2011 as a technique utilizing selective arterial branch microdissection along with controlled hypotension (CH) during anesthesia. In a series of 15 patients, minimally invasive partial nephrectomy was performed on a median tumor size of 2.5 cm. All procedures were completed off-clamp. Hypotension was induced using isoflurane, intravenous nitroglycerin, and esmolol to maintain a mean arterial pressure between 50 and 80 mmHg. Hypotension was induced at the time of tumor resection and reversed once tumor excision was complete and before the renorrhaphy was started. Controlled hypotension lasted between 10 and 25 min, and nadir hypotension was a maximum of 5 min. Selective branch microdissection of the renal artery and vein into the renal sinus was utilized if needed, usually in central tumors. These small third- or fourth-degree branches were clipped to reduce bleeding. There were no intraoperative complications or blood transfusions. All margins were negative on pathology. Acute kidney injury, defined as at least 50 % rise in serum creatinine over baseline, occurred in three patients and resolved in 1–2 days using a protocol of mannitol and Lasix [11].

In 2012, Papalia et al. published a similar method of minimal ischemia partial nephrectomy utilizing controlled hypotension (CH) in 60 patients. For central and hilar tumors, selective microdissection was performed. For peripheral tumors, CH was begun just before incising the renal parenchyma, and for central tumors CH was induced during excision of the deepest portion of the tumor. Median tumor size was 3.6 cm, median operative time was 2 h, and median blood loss was 200 ml. Median times for tumor excision was 13 min and for suturing was 16 min. Median CH time was 14 min. Median nadir MAP was 60 mmHg for a median of 6 min. No intraoperative complications or blood transfusions were necessary. Four patients required one unit of packed red blood cells postoperatively. All margins were negative. Median serum creatinine pre- and postoperatively at discharge were 0.9 and 1.10 mg/dl, respectively. Median eGFR pre- and postoperatively were 87.2 and 75.6 ml/min/1.73 m^2. One-month median postoperative serum creatinine was 1 mg/dl [12].

Although these studies suggested an acceptable rate of complications of CH, the theoretical risk are unappealing associated with low blood flow to the major organs. This risk is increased in patients with coronary artery disease, heart failure, poorly controlled hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, increased intracranial pressure, low flow state to the liver or kidney, or severe anemia. CH has seemed to fallen out of favor while selective arterial clamping continued to develop.

Selective Arterial Clamping

In 2012, Gill et al. used anatomical vascular microdissection and control of tertiary or higher branches of the renal artery to perform “zero ischemia” partial nephrectomy. This was geared toward more endophytic, central, or hilar tumors as opposed to initial trials which targeted peripheral tumors. In this study, 58 cases (15 robotic and 43 laparoscopic) were performed without hilar clamping, but rather with neurosurgical aneurysm micro-bulldog clamps to clamp feeding branching vessels. Preoperative 3D CT with contrast was obtained to provide a road map. Doppler ultrasound was also used to assess for specific segmental or interlobar arteries supplying the tumor. Only 1 in 58 patients required transient hilar clamping. Mean tumor size was 3.2 cm. There were no intraoperative complications. Clavien grade 3 or higher complications were seen in two patients (3.5 %) and included epigastric vessel injury requiring reoperation and septicemia from unknown source requiring prolonged hospital stay. Transfusions were given in 1 patient intraoperatively and in 11 postoperatively. Mean change in serum creatinine was 0.2 mg/dl or 18 %. Mean eGFR decreased by 11.4 ml/min/1.73 m^2 or 13 %. Mag-3 scan in 11 patients showed a mean 10 % decrease in ipsilateral function [13].

In order to detail the technique of vascular microdissection (VMD), Ng et al. studied 44 patients of which 22 underwent zero-ischemia lap or robotic partial nephrectomy with VMD and 22 without VMD. Once again, these patients received 3D CT with contrast to detail the renal artery branching. During the procedure, the main renal artery and vein were circumferentially mobilized and encircled with a vessel loop in case of significant bleeding. Hilar microdissection was performed in medial to lateral orientation in accordance with 3D imaging. Based on tumor location, arterial VMD could be extended intrarenally toward the tumor by making a 1- to 2-cm radial nephrotomy incision on the hilar edge of the kidney directly overlying the anterior portion of the specific arterial branch. A neurovascular aneurysm microsurgical bulldog clamp was placed on specific branches for occlusion. The appearance of tumor and/or Doppler ultrasound was used to confirm proper vascular interruption. Again, controlled hypotension was used if necessary during resection of the deepest portion of the tumor. Patients undergoing VMD had significantly larger tumors (4.3 vs. 2.6 cm, p = 0.011), had closer proximity to the hilum (1.46 vs. 3.26 cm, p = 0.0002), and were more likely to be medial (59.1 vs. 22.7 %, p = 0.017). VMD group also had a higher R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score (8 vs. 6, p = 0.013). There were no differences in polarity, sidedness, or anterior vs. posterior location. No patients in the study required hilar clamping. No patients had a positive cancer margin. Complications were similar. There was no difference in EBL and no need for postoperative transfusion for either group. There was no significant difference in postoperative renal function measured as median increase in serum creatinine and median eGFR decrease at discharge (0.0 with MVD vs. 0.0 without MVD; 0.0 with MVD, −0.4 without MVD ml/mg/1.73 m^2) and 2 months postoperatively (0.2 with MVD vs. 0.1 without MVD, −10.2 ml/min/1.73 m^2 with MVD and −11.2 ml/min/1.73 m^2 without MVD). Thus, VMD in this study was most useful in complex, endophytic, central/hilar tumors as compared to off-clamp procedure [14••].

Desai et al. performed a retrospective analysis to compare superselective versus main artery clamping in 2014. They reviewed 121 consecutive patients undergoing robotic partial nephrectomy. Fifty-eight patients underwent superselective arterial control, and 63 patients underwent main renal artery clamping. Devascularization of only the tumor plus margin and persisting perfusion of the kidney were confirmed with robotic near-infrared imaging with IV indigo-cyanine green and/or color Doppler ultrasound. The superselective clamping group had larger tumors (3.4 vs. 2.6 cm, p = 0.004), higher PADUA score (10 vs. 8, p = 0.009), and more hilar tumors (24 vs. 6 %, p = 0.009). Superselective clamping cases also had longer median operative time (301 vs. 229 min, p < 0.001) and higher perioperative transfusion rate (24 vs. 6 %, p < 0.001). The two groups had similar blood loss and postoperative complications. No patients had a positive margin. The superselective group had better preserved eGFR at discharge (0 vs. 11 % decrease, p = 0.01) and at last follow-up (11 vs. 17 % decrease, p = 0.03). Median follow-up time was 4 months in the superselective group and 6 months in the total hilar clamp group. In 23 patients in the superselective group and 22 in the hilar clamp group, pre- and postoperative CT volumetric data was available and showed superselective cohort had greater preservation of renal parenchyma (95 vs. 90 %, p = 0.07) despite larger tumor size and greater tumor volume (19 vs. 8 ml, p = 0.0002) [15••].

Martin et al. from the Mayo Clinic performed a study to compare total hilar clamping, selective arterial clamping, and off-clamp techniques during minimally invasive partial nephrectomy with follow-up for 1 year. A retrospective analysis from 2007 to 2010 on 68 patients in four groups: selective arterial clamping (SAC) (13), progressive arterial clamping (PAC) (8), total arterial clamping (32), and no clamping (4). Patients were excluded if they had previous surgery or if conversion to radical nephrectomy was performed for deep invasion or multifocality. There were no conversions in the SAC or PAC groups. In the SAC group, the segmental renal arteries were occluded and clips, cautery, or sutures were used to control bleeding in the partial nephrectomy bed. PAC was used in cases where more hemostasis was required, and lap bulldogs were placed on segmental arteries and the main renal artery if necessary. There was a trend in the no-clamping group to be older patients, who have smaller masses, and lower preoperative eGFR, but no statistically significant difference between the groups was present. There was a significantly shorter total renal ischemia time with the progressive technique compared to the total clamp technique (18 vs. 32 min). The mean clamp time in the SAC group was 22 min. However, no significant difference was seen in intermediate-term GFR between the four groups at a mean follow-up of 411 days (−2.5, −66, −7.8, −6.8 ml/min/1.73 m^2). There was no significant percent change in ipsilateral renal function on MAG-3 renal scan (−2.5, −4.9, −5.5, −4.8 %). This study suggests that if technique selection choices are made wisely, then renal function outcomes among clamping, no clamping, SAC, and PAC at 1 year may be equivalent [16••].

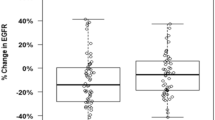

Other technologies such as intraoperative guidance with fluorescence contrast may help delineate the margins of the tumor and reduce need for clamping. McClintock et al. described using near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) during selective arterial clamping to attempt to preserve kidney function. NIRF works through IV administration of fluorescent contrast agent indocyanine green at a dose of 5–7.5 mg. This agent emits a light in the near infrared wavelength (700–850 nm) after activation by a light-emitting diode. Ischemic tissue should not fluoresce and tumor tissue fluoresces less strongly as compared to normal renal parenchyma. Forty-two study patients were matched to control patients undergoing robotic partial nephrectomy with main artery clamping. There was no significant difference between baseline characteristics, operative time, warm ischemia time, estimated blood loss, or length of stay. Selective clamping with NIRF was associated with superior kidney function with improved postoperative eGFR (78.2 vs. 68.5 ml/min/1.73 m^2, p = 0.04), absolute reduction of eGFR (−2.5 vs. −14 ml/min/1.73 m^2, p < 0.01), and percent change in eGFR at discharge (−1.9 vs. −16.8 %, p < 0.01). These trends persisted at 3-month follow-up but were not statistically significant. The true utility of NIRF in this setting is still undefined [17].

Other such tools include a three-dimensional dynamic renal vascular model based on dual-source CT angiography to aid in preoperative planning which was shown to provide 93.9 % predictive accuracy with no positive margins in a study of 82 patients undergoing SAC partial nephrectomy [18]. In addition, a study by Furukawa et al. showed console-integrated real-time 3D image overlay for assistance with SAC partial nephrectomy [19].

Off-Clamp

While selective ischemia offers reduced ischemia to “normal” portions of the ipsilateral kidney, off-clamp methods were also reported to have satisfactory results in appropriately selected patients. Rais Bahrami et al. in 2011 performed a retrospective study in which they reviewed 390 patients (264 underwent hilar clamping and 126 underwent off-clamping procedure) who underwent laparoscopic partial nephrectomy between 2006 and 2010. Patients were stratified in each group by their clinical T stage as well. There was no difference between the two groups in age, sex, ASA, BMI, tumor laterality, or tumor polar location. There was a significantly lower mean tumor size and higher proportion of exophytic tumors in the off-clamp group (p < 0.001). EBL was higher in the off-clamp group, but there was no difference in transfusion rate between the two groups. At 6 months postoperatively, changes in serum creatinine levels were found to be significantly less affected in the off-clamp group (6.6 vs. 14.7 %, p = 0.04), and this was not found to differ based on tumor size (T1a, T1b, T2) [20]. These are promising results which were supported by other studies.

In a larger cohort study, George et al. performed a retrospective study of 439 patients undergoing laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) between January 2006 and March 2010. Two hundred eighty-nine LPNs were performed on-clamp and 150 LPNs were performed off-clamp. Off-clamp LPN was performed in select patients with cT1b or lower stage. The off-clamp and on-clamp groups had similar age, gender, ASA, BMI, and preoperative eGFR. The mean tumor size in the off-clamp group was 2.7 cm and in the on-clamp group was 3.3 cm (p = 0.003). Endophytic tumors were significantly more likely to be performed on-clamp (p < 0.001). Low complexity tumors were more likely to be done off-clamp (62 % in off-clamp and 36 % in on-clamp). More tumors <4 mm from the collecting system were performed in the on-clamp group (51.8 %) than on the off-clamp group (27.5 %). Operative time was comparable. EBL was larger in the off-clamp group although there was no significant difference in transfusion rate (338.4 vs. 276.8 ml, p = 0.021). Mean WIT in the on-clamp group was 25.5 min. The on-clamp group had higher postoperative complications (11 vs. 22 %, p = 0.009). The change in creatinine, percentage change in creatinine, and percentage change in eGFR at 6 months after surgery were significantly decreased in the off-clamp cohort (p = 0.019, p = 0.024, p = 0035) [21].

Given the number of small cohort results, Liu et al. performed a meta-analysis-reviewed 10 retrospective studies with 728 off-clamp and 1267 on-clamp procedures. They showed no baseline differences between the two groups in age, sex, BMI, tumor size, and preoperative eGFR. Tumor location did differ with off-clamp tumors being less endophytic. The off-clamp group had higher blood transfusion rate (15.3 vs. 6.3 %, p = 0.02), lower postoperative complication rate (12.5 vs. 18 %, p = 0.002), and lower positive margin rate (2.4 vs. 3.2 %, p = 0.02). Five trials measured eGFR pre- and postoperatively and showed better renal function preservation in the off-clamp group with a mean difference of 5.81 ml/min.1.73 m^2 between pre- and postoperative eGFR. When sensitivity analysis was performed, the off-clamp group still had a significantly higher blood transfusion rate and renal function preservation, but there was no statistical difference in positive margin rate or postoperative complication rate [22]. These studies demonstrate that off-clamp procedures may be a preferred option in less complex, more exophytic tumors. These findings are supported by meta-analysis performed by Trehan et al. as well [23].

Effects on Renal Function

Most studies show a decline in global renal function of 10 % after partial nephrectomy with limited compensatory hypertrophy [24]. Historically, it was believed that every moment of clamp time reduced overall kidney function [8], but, more recently, the remaining kidney volume after resection and preoperative kidney function have been shown to be of critical importance and may be more predictive than WIT.

Komninos et al. performed a retrospective study on 180 patients who underwent robotic partial nephrectomy from 2007 to 2013 that were nonrandomly stratified into off-clamp (group 1), selective artery clamp (group 2), and main artery clamp (group 3). There was no statistically significant difference in baseline characteristics between the groups including preoperative eGFR, except those patients who underwent off-clamp procedure had smaller tumors with lower complexity. The median follow-up of each group respectively was 45, 20, and 47 months. The median clamp time for groups 2 and 3 were 18 and 24.8 min, respectively. Patients in the off-clamp group had shorter operating times (120 vs. 163 vs. 175 min, p < 0.01). The selective artery clamping group had the greatest EBL (100 vs. 500 vs. 200 ml, p < 0.01) and longer LOS (3 vs. 4 vs. 3 days, p = 0.02). There were similar transfusion rates, surgical margin rates, and complications. A significant reduction in postoperative creatinine level, eGFR, and percentage change in eGFR during the first 3 months of follow-up was seen in the main artery clamp group compared to the others. These differences were not present at 6 months or 1 year after surgery or at the time of most recent eGFR. Patients with low RENAL scores who had an off-clamp or selective clamping procedure with short operative times were more likely to have normal renal function (eGFR < 90 ml/min/1.73 m^2) 7 days after surgery. After 7 days, only low RENAL score, preoperative eGFR, and type of clamp procedure were predictive of normal renal function. Only age and preoperative eGFR correlated with normal eGFR after 1 year from surgery. Moderate to severe CKD (stage > or = III, eGFR, 60 ml/month/1.73 m^2) was seen in the main artery clamp group after 1 week from surgery but not after the first postoperative month [25••]. Therefore, only a short-term postoperative difference in renal function was seen between different groups. Selective arterial clamping or off-clamp procedures may be most important in those patients who are already at risk for chronic kidney disease.

In another study by Shah et al. in 2015, 315 patients undergoing laparoscopic partial nephrectomy between 2006 and 2011 were evaluated. Two hundred nine patients underwent on-clamp procedure, and 106 patients underwent off-clamp LPN. There was no difference in the groups between gender, BMI, HTN/DM, ASA, and preoperative eGFR. Off-clamp tumors were statistically smaller (3.4 cm for on-clamp and 3.0 cm for off-clamp, p < 0.033) and more likely to be exophytic. RENAL score was greater in the on-clamp group (7.4 vs. 6.7, p = 0.017). There was no difference in positive margin rate, OR time, or EBL. Mean WIT in on-clamp was 26 min. No significant difference was seen in eGFR between type of procedure they had, if eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m^2, or when comparing clamping <30 min to clamping >30 min. When matched for nephrometry score, there was no difference in eGFR between the on- and off-clamp groups. The immediate decrease in eGFR after hilar clamping was significantly worse compared to off-clamp but this was not significant after 6 months and up to 5 years [26]. An additional study in 2015 by Kalingal et al. showed no correlation between duration of ischemia and renal functional change [27].

Zhang et al. performed a retrospective study from 2007 to 2014 in 83 solitary kidney patients managed with minimally invasive and open partial nephrectomy. Patients were followed with CT or MRI with contrast after surgery if eGFR was greater than 30 ml/min/1.72 m^2 and daily serum creatinine after surgery until peak value was taken. The study evaluated the degree of acute kidney injury (AKI) after surgery and the prognostic significance. AKI was defined by the RIFLE classification scheme. The median tumor size was 4.0 cm, RENAL score was 8, and WIT used in 39 patients was median of 20 min. Median parenchymal mass reduction was 11 %. Median recovery from ischemia was 99 % in patients without AKI and 95 % for those with grade 1 AKI, 90 % for those with grade 2 AKI, and 88 % for those with grade 3 AKI with follow-up to 12 months after surgery [28•]. This suggests that those with chronic renal failure are at higher risk of postoperative renal dysfunction and should warrant a different pathway than those with normal baseline renal function. For patients with poor preoperative renal function or a solitary kidney, any significant nephron loss may make these patients dialysis dependent. Thus, off-clamp or selective arterial clamping may be preferred in these cases if reasonable.

See Table 1 for a summary of key studies in off-clamp, selective arterial clamping, and complete hilar clamping techniques.

Conclusion

Historically, length of WIT was believed to be the most important operative factor determining long-term renal function. However, more recent studies show that preoperative eGFR and the volume of functional kidney remaining may be better predictors.

The technique chosen during partial nephrectomy must be based on surgeon experience. For small, exophytic, mild complexity tumors, the off-clamp procedure may be the most efficient with the risk being potential significant blood loss. For more complex, central, or hilar tumors, in a patient with two kidneys and normal renal function, the surgeon can decide whether selective arterial clamping or main hilar clamping is the best decision. Our preference is to perform standard hilar clamping for most tumors except the very small (less than 2 cm) and nearly completely exophytic tumors. Even for these small tumors, we would preemptively perform a hilar dissection to obtain rapid hilar control if bleeding was encountered. Other modalities such as Doppler ultrasound, NIRF, or 3D imaging overlay will play an increasing role. Advanced techniques such as superselective vascular microdissection probably should be reserved for surgeons well along their learning curve and in specialized cases such as central tumors, solitary kidneys, or poor preoperative renal function.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Campbell SC, Novick AC, Belldegrun A, et al. Guideline for management of the clinical T1 renal mass. J Urol. 2009;182:1271–9.

Papalia R, Simone G, Ferriero M, et al. Laparoscopic and robotic partial nephrectomy without renal ischaemia for tumours larger than 4cm: perioperative and functional outcomes. World J Urol. 2012;30:671–6.

Kreshover JE, Kavoussi LR, Richstone L. Hilar clamping versus off-clamp laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for T1b tumors. Curr Opin Urol. 2013;23:399–402.

Scosyrev E, Messing EM, Sylvester R, et al. Renal function after nephron-sparing surgery versus radical nephrectomy: results from EORTC randomized trial 30904. Eur Urol. 2014;65:372–7.

Gill IS, Kavoussi LR, Lane BR, et al. Comparison of 1,800 laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomies for single renal tumors. J Urol. 2007;178:41–6.

Abuelo JG. Normotensive ischemic acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:797–805.

Secin FP. Importance and limits of ischemia in renal partial surgery: experimental and clinical research. Adv Urol 2008:102461

Thompson RH, Lane BR, Lohse CM, et al. Every minute counts when the renal hilum is clamped during partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol. 2010;58:340–5.

Thompson RH, Lane BR, Lohse CM, et al. Renal function after partial nephrectomy: effect of warm ischemia relative to quantity and quality of preserved kidney. Urology. 2012;79:356–60.

Nguyen MM, Gill IS. Halving ischemia time during laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. J Urol. 2008;179:627–32.

Eisenberg MS, Patil MB, Thangathurai D, et al. Innovations in laparoscopic and robotic partial nephrectomy: a novel ‘zero ischemia’ technique. Curr Opin Urol. 2011;21:93–8.

Papalia R, Simone G, Ferriero M, et al. Laparoscopic and robotic partial nephrectomy with controlled hypotensive anesthesia to avoid hilar clamping: feasibility, safety and perioperative functional outcomes. J Urol. 2012;187:1190–4.

Gill IS, Patil MB, Abreu ALDC, et al. Zero ischemia anatomical partial nephrectomy: a novel approach. J Urol. 2012;187:807–15.

Ng CK, Gill IS, Patil MB, et al. Anatomic renal artery branch microdissection to facilitate zero-ischemia partial nephrectomy. European Urology. 2012;61:67–74. Hilar microdissection was performed in medial to lateral orientation using preoperative 3D imaging for guidance and extended intrarenally for selective arterial clamping using neurovascular aneurysm microsurgical bulldog clamp. Compared to off clamp, those undergoing SAC had larger tumors, were more hilar, and more complex. No significant difference in renal function between SAC and off-clamp procedure up to 2 months post-operatively.

Desai MM, Abreu ALDC, Leslie S, et al. Robotic partial nephrectomy with superselective versus main artery clamping: a retrospective comparison. Eur Urol. 2014;66:713–9. SAC compared to hilar clamping. SAC group composed of patients with larger, more complex, more hilar tumors with longer operative time and higher transfusion rates. SAC group had better preserved eGFR at 4–6 months post-operatively.

Martin GL, Warner JN, Nateras RN, et al. Comparison of total, selective, and nonarterial clamping techniques during laparoscopic and robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy. Journal of Endourology 2012;26(2):152–156. No difference seen in post-operative eGFR between SAC, off clamp, and hilar clamp groups at mean follow-up of 411 days. Off clamping group was older, had smaller tumors, and lower preoperative eGFR.

McClintock TR, Bjurlin MA, Wysock JS, et al. Can selective arterial clamping with fluorescence imaging preserve kidney function during robotic partial nephrectomy? J Urol. 2014;84(2):327–34.

Shao P, Tang L, Li P, et al. Application of a vascular model and standardization of the renal hilar approach in laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for precise segmental artery clamping. Eur Urol. 2013;63:1072–81.

Furakawa J, Miyake H, Kazushi T, et al. Console-integrated real-time three-dimensional image overlay navigation for robot-assisted partial nephrectomy with selective arterial clamping: early single-centre experience with 17 cases. Int J Med Robotic Comput Assisted Surg. 2014;10:385–90.

Rais-Bahrami S, George AK, Herati AS, et al. Off-clamp versus complete hilar control laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: comparison by clinical stage. BJU Int. 2011;109:1376–81.

George AK, Herati AS, Srinivasan AK, et al. Perioperative outcomes of off-clamp vs complete hilar control laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. BJU Int. 2012;111:E235–41.

Liu W, Li Y, Chen M, et al. Off-clamp versus complete hilar control partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endourol. 2014;28(5):567–76.

Trehan A. Comparison of off-clamp partial nephrectomy and on-clamp partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Int. 2014;93(2):125–34.

Mir MC, Ercole C, Takagi T, et al. Decline in renal function after partial nephrectomy: etiology and prevention. J Urol. 2015;193:1889–98.

Komninos C, Shin TY, Tuliao P, et al. Renal function is the same 6 months after robot-assisted partial nephrectomy regardless of clamp technique: analysis of outcomes for off-clamp, selective arterial clamp and main artery clamp techniques, with a minimum follow-up of 1 year. BJU Int. 2015;115:921–8. Significant difference seen at 3 months in eGFR reduction in hilar clamping group compared to SAC and off clamp groups, however this difference was not present at 6 months or at 1 year. After 7 days from surgery, only low RENAL score, preoperative eGFR, and type of clamp procedure were predictive of normal renal function. At 1 year follow-up, only age and preoperative eGFR correlated with normal eGFR.

Shah PH, George AK, Moreira DM, et al. To clamp or not to clamp? Long-term functional outcomes for elective off-clamp laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. BJU Int. 2015;117:293–9.

Kallingal GJS, Weinberg JM, Reis IM, et al. Long-term response to renal ischaemia in the human kidney after partial nephrectomy: results from a prospective clinical trial. BJU Int. 2015. doi:10.1111/bju.13192.

Zhang Z, et al. Acute kidney injury after partial nephrectomy: role of parenchymal mass reduction and ischemia and impact on subsequent functional recovery. Eur Urol 2015. Median recovery in eGFR from ischemia from partial nephrectomy in solitary kidney was 99% in those without preoperative AKI, 95% for those with grade 1 AKI, 90% for those with grade 2 AKI, and 88% for those with grade 3 AKI up to 12 months after surgery.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Mona Yezdani MD, Sue-Jean Yu, and David I. Lee each declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Minimally Invasive Surgery

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yezdani, M., Yu, SJ. & Lee, D.I. Selective Arterial Clamping Versus Hilar Clamping for Minimally Invasive Partial Nephrectomy. Curr Urol Rep 17, 40 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11934-016-0596-0

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11934-016-0596-0