Abstract

Purpose of Review

In the clinical evaluation of inflammatory arthritis and the research into its pathogenesis, there is a growing role for the direct analysis of synovial tissue. Over the years, various biopsy techniques have been used to obtain human synovial tissue samples, and there have been progressive improvements in the safety, tolerability, and utility of the procedure.

Recent Findings

The latest advancement in synovial tissue biopsy techniques is the use of ultrasound imaging to guide the biopsy device, along with evolution in the characteristics of the device itself. While ultrasound guided synovial biopsy (UGSB) has taken a strong foothold in Europe, the procedure is still relatively new to the United States of America (USA).

Summary

In this paper, we describe the expansion of UGSB in the USA, elucidate the challenges faced by rheumatologists developing UGSB programs in the USA, and describe several strategies for overcoming these challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction: Synovial Tissue: The Target Organ of Inflammatory Arthritis

Synovial inflammation is the hallmark of the systemic autoimmune arthritides, of which rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most prevalent and extensively studied disease. RA has been studied for over 200 years, but despite extensive investigation into the genetics, pathogenesis, and clinical characteristics of RA, the key to conquering this heterogenous disease has not been found and there is no known cure or simple treatment strategy [1]. Unmet needs in rheumatoid arthritis include (1) prevention of disease by identifying persons at risk for RA and developing a mechanism to disrupt the pathways that lead to disease development, (2) personalization of therapeutics to identify the therapy or therapies with the highest chance of achieving disease-free remission, (3) prevention of articular damage and disease-related extra-articular damage, and (4) identification of patient characteristics to guide medication tapering once disease control has been achieved [2]. Given that the synovium is the target organ in RA, and that synovial inflammation is the hallmark of RA, the expansion of research efforts to include a detailed study of synovial tissue in both early and established RA may unlock the secrets of this disease, and perhaps deepen our understanding of other inflammatory disorders.

Sampling Synovial Tissue: Prior Methods

The sampling of synovial tissue from patients with arthritis has evolved significantly over the past century. Historically, synovial tissue was obtained through arthrotomy. Arthrotomy can be done in most superficial and deep joints. By definition, an arthrotomy is a surgical procedure where the joint space is entered. In 1932, the first report of synovial tissue sampling from superficial joints using a percutaneous device was published [3]. Twenty years later, Mayo Clinic researchers described their use of a blind needle technique for large joints [4]. This was refined in 1962 with the development of the Parker Pearson technique allowing biopsy of large and some small joints [5]. Synovial biopsy through the arthroscope was perfected in the 1960s [6, 7]. Several rheumatology centers utilized arthroscopy during the 1980s and 1990s in inflammatory and degenerative arthritis research [8]. However, the use of arthroscopy in the rheumatology clinic waned in the new millennium in part due to the revolutionary impact of TNF-alpha inhibition on the disease activity of inflammatory arthritis. These biologic agents worked so well that voluminous synovitis became rare, and the tissue thus became harder to access.

Introduction of Ultrasound-Guided Biopsy Techniques and Confirmation of Their Safety and Efficacy

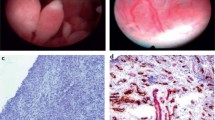

The combination of ultrasound guidance with a mechanical guillotine needle or a portal and forceps approach (Fig. 1) provided a safer and more tolerable biopsy experience while still allowing the rheumatologist to select areas of interest for biopsy [9, 10]. In 1997, ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy (UGSB) using a mechanical biopsy needle was first reported by van Vugt, who was working in the Netherlands [10]. This was the beginning of a new era in synovial sampling. This synovial biopsy technique allowed the acquisition of synovial tissue with ultrasound guidance for both research and clinical purposes from small as well as large joints through a tolerable and safe procedure.

From 1997 to 2015, UGSB was performed in an expanding number of clinical sites in Europe. Over that period, European scientists demonstrated the safety of the procedure and described best practices for optimal patient selection, biopsy technique, and tissue processing. The safety and tolerability of UGSB were described in an analysis of 524 synovial biopsy procedures [11]. Another group reported on the safety of 93 biopsies with over 75% of patients reporting that they were very likely or somewhat likely to agree to a repeat biopsy [12].

UGSB can be performed in an outpatient exam room with sterile procedure (Fig. 1). The procedure is described in detail in an earlier publications. [12, 13] Biopsy devices include the guillotine needle device and the portal and forceps device (Fig. 2). Ultrasound guidance is used to identify the site of the biopsy and the ultrasound is used throughout the biopsy procedure to ensure adequate tissue sampling (Fig. 3).

Biopsy devices: A Guillotine needle—Needle is inserted into the area of interest directly or via a trocar. B Guillotine needle cutting surface—Tissue is pressed ito the well (marked with an asterisk (*)), and when the trigger is engaged, the needle snaps back and cuts and captures the tissue. C Portal and forceps: Portal is inserted into the area of interest using a modified Seildinger technique. Portal is orange and white in this photo. Metal forceps are inserted into the portal to obtain tissue from the area of interest. D Metal forceps with exposed cutting area (marked with an asterisk (*))

Expansion to the United States of America

The AMP-RA Training Program

In 2015, through the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Accelerating Medicines Partnership-Rheumatoid Arthritis (AMP-RA) program, UGSB techniques were introduced in the United States of America (USA). As part of the AMP-RA program, 9 rheumatologists (including the 4 authors of this paper) and 3 radiologists from the USA traveled to England to be trained in UGSB by Stephen Kelly, MD, Costantino Pitzalis, MD/PhD, and Andrew Filer, MD/PhD. During the 5-day program in 2015, these musculoskeletal ultrasound-trained physicians attended lectures on the history, utility, and research applications of UGSB. The trainees then observed the process of preparation for the UGSB procedure followed by the performance of multiple synovial biopsies using both the semi-automated guillotine needle and the portal and forceps approach. The training concluded with a hands-on experience in a cadaver lab. The trainees were supervised and observed while independently performing ultrasound guided biopsies of cadaveric knee, ankle, and wrist joints.

Expansion of Training in UGSB in the USA

The first fully American UGSB training course was conducted at Northwestern in 2015 with a single instructor (AMM), to recapitulate the cadaver lab portion of the British course to allow those previously trained in England to refresh their skills with the guillotine needle before initiating the AMP-RA project.

As the AMP-RA research program initiated patient recruitment, a separate coalition of six American universities named the RhEumatoid Arthritis Synovial Tissue Network (REASON), with Dr. Richard Pope from Northwestern University as the principal investigator, sought the recruitment and training of additional American proceduralists who had never been trained in England. Thus, five additional training weekends were held at Northwestern with the same instructor (AMM) over the course of the following 3 years (2016–2019). These courses were intended to reconstruct the entire British experience including the lectures, in-person observation of an actual needle biopsy and an actual portal and forceps biopsy, and a hands-on experience in the cadaver lab at Northwestern Simulation. A total of approximately 40 proceduralists were trained in these courses, initially for the REASON program and later including others who were interested in learning the UGSB procedure.

USSONAR Training Courses

As the demand for training grew, the four authors of this paper formed the Ultrasound Guided Synovial Biopsy interest group (UGSBy) and began developing a curriculum for biopsy courses based on the techniques learned in the UK, the Northwestern training courses, and ongoing experience with research and clinical UGSB in the USA.

The first course from this series was held in February 2022 at Northwestern. This was followed by a series of 3 courses developed in conjunction with the Ultrasound School of North American Rheumatologists (USSONAR) in 2022 (New York) and 2023 (California and Florida). Logistical and financial support from USSONAR enabled courses to be held throughout the country. The attendance at each course was limited to 16 students to ensure a 4:1 learner-to-faculty ratio. Learners were given didactic lectures reviewing the history of UGSB, clinical and research applications of UGSB, and procedural techniques. The learners were able to practice setting up a sterile environment and donning sterile gowns and gloves. In the cadaver lab, the learners were given 3 h to practice biopsy techniques on ankles, knees, wrists, and MCP joints. Utilizing self-reported questionnaires, longitudinal data were collected from the students to assess learner confidence in the procedure and the number of procedures performed after training was completed. The current manuscript conveys the lessons learned by the four UGSBy founders as they incorporated synovial biopsies in their respective institutions and practices and subsequently established the USSONAR-sponsored training courses.

Challenges Faced by Rheumatologists in Developing UGSB Programs in the USA

Following the training experience, learners have found numerous obstacles that had to be surmounted to begin performing synovial biopsy independently. Common challenges included (1) institutional administrative challenges, (2) logistical challenges, (3) financial considerations, (4) lack of ultrasound experience among rheumatologists interested in learning USGB, (5) first unsupervised biopsy hesitancy, and (6) delay in implementing biopsy skills.

Institutional Administrative Challenges

The majority of the AMP-RA cohort and the Northwestern-trained proceduralists are academic physicians working in medium to large healthcare systems. As such, they are required to obtain research and/or clinical privileges from their academic institutions to perform this procedure. Those in private practice needed to obtain privileges from their practice group and coverage from their malpractice insurance carrier. As expected, there has been variation in policies and procedures among institutions, but some proceduralists had more difficulty than others in obtaining approval from their home institution to perform this procedure. One of the main objections posed by credentialing committees was the lack of another physician in their institution who could also perform the procedure or the lack of another physician who could proctor or observe the first few procedures to certify the proceduralist as being competent. In parallel, proceduralists were also concerned with performing their first biopsy independently without having a more experienced person locally to turn to for verification or questions.

In order to address this barrier, as the procedure becomes more common in the USA and a critical mass of proceduralists are trained, the institutions and practice groups will have more experience in credentialing proceduralists in UGSB.

Logistical Challenges

The list of necessary supplies for UGSB usually includes approximately 20 items which are purchased from 3–5 different vendors. The supplies needed to perform a biopsy vary based on availability, procedure room setup, joint biopsied, and operator preference. Furthermore, as design improvements have been made for both biopsy needles and associated supplies, the list of preferred biopsy supplies has evolved. While the physician experienced in performing biopsies is familiar with the advantages and disadvantages of different types of drapes, needles, and probe covers, the novice may find the task of selecting supplies daunting. The lack of a standardized supply list and the diversity of options when selecting supplies can pose a challenge to the rheumatologist preparing to perform their first biopsy. This challenge is compounded by supply chain disruptions, which have become ubiquitous since the COVID-19 pandemic, and when working within a large institution, by purchasing agreements with specific vendors. When a certain item is not sold by a vendor contracted with a healthcare system, the rheumatologist may have to navigate a host of bureaucratic hurdles to obtain the desired item. Since the rheumatologist novice to the biopsy procedure does not have experience using the supplies, the process of having to substitute recommended supplies for available supplies poses additional challenges.

To address the barrier of obtaining biopsy supplies, training programs can provide a list of specific recommended supplies, along with the vendor and item number. This preferred supply list can be updated as new, improved supplies become available. If planning to perform synovial biopsies for a research project funded by a third party, the rheumatologist may request that the contract research organization (CRO) provide biopsy kits with the necessary supplies. Furthermore, rheumatologists novice in the biopsy procedure may consult more experienced individuals for recommendations for preferred biopsy supplies and ways to obtain them. The experienced biopsy operator can also advise the novice on modifications to the list when necessary. We recognize that while a preferred supply list can be helpful, over time an individual may modify their supply list to suit their needs, resources, and preferences.

Financial Considerations

The synovial biopsy procedure requires an investment of both time and financial resources. The procedure requires a conventional ultrasound machine, which can be leased or purchased. While handheld devices are more affordable, they often lack the resolution necessary for UGSB. The proceduralist must then dedicate many hours to the mastery of musculoskeletal ultrasound and then to ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy training. The proceduralist will then need to procure supplies and train support staff. At least one trained assistant is required for the procedure, although some proceduralists have 2 trained assistants present at each biopsy. Purchased supplies may include non-disposable items such as a specialized procedure table and additional work surfaces (e.g., wheeled Mayo stand) in addition to disposable supplies such as biopsy needles. The cost of disposable supplies used in a single ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy can vary from 100 to 200 US dollars. The biopsy needle is usually the most expensive disposable item consumed, and at times a needle malfunctions, or the size of the needle is found to be inappropriate, and a second needle must be used.

In addition to the cost of supplies, the time spent performing a biopsy presents a significant opportunity cost. Rheumatologists who are experienced in the procedure may be able to perform it in about an hour, but we generally recommend scheduling 90 min for the procedure, especially for the novice. We must, therefore, account for the cost of 90 min of productivity for the physician and at least one assistant. Physician productivity must account for direct charges, indirect charges, and facility fees. At the current reimbursement rates, a UGSB presents a financial loss. Currently, there are no billing codes (CPT/RVU codes) that accurately describe the procedure in the USA. Proceduralists have historically used arthrotomy or interventional radiology billing codes.

The direct and indirect financial disincentives described above can be overcome with the creation of billing codes that accurately describe the procedure and are linked to appropriate reimbursement. The reimbursement needs to account for both the direct costs of performing the biopsy and the opportunity costs of physician and staff time.

Lack of Ultrasound Expertise Among Trainees

To safely perform an ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy, the proceduralist must be proficient in ultrasound-guided arthrocentesis and diagnostic musculoskeletal ultrasound. Thus, inadequate training in sonography is a barrier to learning this technique. If individuals who are not already comfortable with ultrasound-guided procedures attend biopsy training, they are less likely to feel comfortable implementing their biopsy skills following the course.

This barrier to more widespread adoption of the biopsy technique can be lowered by ensuring that UGSB training is focused on rheumatologists experienced in musculoskeletal ultrasound, who are already comfortable performing arthrocentesis of small, medium, and large joints under direct ultrasound guidance. Proficiency in ultrasound can be assessed before training course registration in a variety of ways. While musculoskeletal ultrasound certification does attest to a certain level of competence, many rheumatologists in the USA have attained advanced ultrasound skills without participating in the credentialing process. Furthermore, the credentialing process is designed to ensure a minimal competency benchmark, not to test advanced skills. The volume and frequency of musculoskeletal ultrasound scans performed likely better attest to a rheumatologist’s advanced skills than credentials. Further, the expansion of the ultrasound-trained rheumatology workforce will also increase the number of rheumatologists who are candidates for UGSB training.

First Unsupervised Biopsy Hesitancy

Rheumatologists trained in USGB often must perform their first biopsy with no mentor present and no supervision. Naturally, this first experience is often accompanied by hesitancy and anxiety. Furthermore, if the rheumatologist has a negative experience performing the first biopsy, the proceduralist may be very reluctant to perform additional biopsies.

To lower this barrier, the first biopsy experience needs to be as comfortable and technically simple as possible. The patient selected for the first biopsy should be trusting and cooperative. An anxious patient can make the biopsy experience more challenging for the physician performing the procedure. The first biopsy should be scheduled in a three-hour time block, with plenty of time both before and after the procedure. Going through at least one mock biopsy with the assistant a day or two before the first biopsy is also highly recommended. Medium and small joint biopsies are more technically challenging. For this reason, the first biopsy should be performed on a knee with a significant effusion and prominent synovitis by grayscale ultrasound. Identifying a patient with the right temperament and a joint with prominent pathology will contribute to a successful first procedure and lead to more confidence in performing additional biopsies. After three or four successful UGSBs of the knee, the proceduralist may attempt biopsies of the more challenging medium and small joints. After a critical mass of proceduralists is trained, there will be local proceduralists able to assist novice proceduralists with their initial biopsies. Currently, most sites do not have more than one proceduralist, but this will expand over time.

Another way to mitigate the barrier presented by the first unsupervised biopsy is the utilization of remote supervision. A live streaming video from a camera positioned from the operator’s perspective coupled with hands-free audio allows all aspects of the procedure from preparation through landmark recognition, point of entry, and the subsequent performance of needle biopsy as the ultrasound display to be in the field of view of the remote observer. This model has been used successfully in surgery and in the autopsy suite [14, 15]. Alternative strategies that have demonstrated success where on-site instruction is unavailable include remote ultrasound training. The USSONAR program demonstrated that cohort training in elementary MSK ultrasound through remote supervision is effective. There are now hundreds of rheumatologists competent in musculoskeletal ultrasound who were trained through remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic [16].

Delay in Implementing Biopsy Skill

As with learning any new skill, the rheumatologist’s confidence and proficiency in performing the UGSB technique will increase with biopsy experience. After the training experience, the trainee’s first biopsy may be months later. In the AMP program, most sites conducted their first biopsy more than 12 months after the initial training course. Delays may be due to challenges in securing the necessary supplies, obtaining institutional credentials for the procedure, obtaining institutional permission to perform biopsies, and, if done for research purposes, securing funding for a biopsy-based research grant.

Further, once the first biopsy is performed, sometimes subsequent biopsies are often few and infrequent. With insufficient volume and frequency, the rheumatologist may lose confidence in their skill, have difficulty recalling the nuances of performing the procedure, and not get a chance to improve from their experience. Additionally, attaining comfort and competence with the procedure in one joint does not necessarily translate to other joints.

The adoption of new procedures has faced similar hurdles in other specialties, including surgical specialties. In a study where 19 academic otolaryngologists were interviewed, barriers to implementing a new procedure included hesitation to communicate to patients that the procedure was new and had unknown complications, substantial learning curve, and too few indications for the new procedure. These otolaryngologists noted that in novel procedures, demonstration of improved outcomes and increased efficiency helped to bolster the implementation of the new procedure [17]. For UGSB, to lower this barrier, the first biopsy should be performed as soon as possible after the training session. Ensuring that newly learned skills are implemented quickly, and that procedure frequency is sufficient will produce more confidence and competence, which is likely to produce more widespread application of the biopsy skill. In addition, as the procedure becomes more widely used and indications expand, the barriers will lower.

Conclusions and Looking Towards the Future

Synovial biopsy techniques and application have evolved over the past century and most rapidly in the past 25 years. Advances in device technology along with the addition of ultrasound guidance have enabled the synovial biopsy to become a well-tolerated in-office procedure. Furthermore, ultrasound guidance allowed for the acquisition of tissue from both large and small joints, which broadened the scope of its research and clinical applications.

While there are multiple barriers to the widespread adoption of USGB in the USA, these barriers can be overcome. Currently, the greatest needs include expanding the American workforce, which is competent in performing ultrasound, streamlining training in USGB, breaking down the barriers that prevent trained rheumatologists from performing their first biopsy, and developing further clinical and research applications for ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy. As UGSB is more widely used, making synovial tissue more accessible for both clinical and research applications, new frontiers may be opened in our understanding of synovial pathology and inflammatory disorders.

References

Kaltsonoudis E, Pelechas E, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA. Unmet needs in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis An observational study and a real-life experience from a single university center. In Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48(4):597–602 (WB Saunders).

Mankia K, Di Matteo A, Emery P. Prevention and cure: the major unmet needs in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. J Autoimmun. 2020;1(110):102399.

Forestier J. Instrumentation pour biopsie médicale. CR Séances Soc Biol Filiales. 1932;110:388–402.

Polley HF, Bickel WH. Punch biopsy of synovial membrane. Ann Rheum Dis. 1951;10(3):277.

Parker RH, Pearson CM. A simplified synovial biopsy needle. Arthritis Rheum: Off J Am Coll Rheumatol. 1963;6(2):172–6.

Watanabe M, Takeda S, Ikeuchi H. Atlas of arthroscopy. Tokyo (JPN): Igaku-Shoin; 1979.

DeMaio M. Giants of orthopaedic surgery: Masaki Watanabe MD. Clin Orthop Relat Res®. 2013;471:2443–8.

Ike RW, Arnold WJ, Kalunian KC. Arthroscopy in rheumatology: where have we been? Where might we go? Rheumatology. 2021;60(2):518–28.

Koski JM, Helle M. Ultrasound guided synovial biopsy using portal and forceps. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(6):926–9.

Van Vugt RM, Van Dalen A, Bijlsma JW. Ultrasound guided synovial biopsy of the wrist. Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26(3):212–4.

Just SA, Humby F, Lindegaard H, de Bellefon LM, Durez P, Vieira-Sousa E, Teixeira R, Stoenoiu M, Werlinrud J, Rosmark S, Larsen PV. Patient-reported outcomes and safety in patients undergoing synovial biopsy: comparison of ultrasound-guided needle biopsy, ultrasound-guided portal and forceps and arthroscopic-guided synovial biopsy techniques in five centres across Europe. RMD Open. 2018;4(2):e000799.

Kelly S, Humby F, Filer A, Ng N, Di Cicco M, Hands RE, Rocher V, Bombardieri M, D’Agostino MA, McInnes IB, Buckley CD. Ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy: a safe, well-tolerated and reliable technique for obtaining high-quality synovial tissue from both large and small joints in early arthritis patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(3):611–7.

Ben-Artzi A, Horowitz DL, Mandelin AM II, Tabechian D. Best practices for ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy in the United States. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2023;30:101834.

Vodovnik A, Aghdam MR, Espedal DG. Remote autopsy services: a feasibility study on nine cases. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(7):460–4.

Miller JA, Kwon DS, Dkeidek A, Yew M, Hisham Abdullah A, Walz MK, Perrier ND. Safe introduction of a new surgical technique: remote telementoring for posterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82(11):813–6.

Valle A, Mahmood SN. The current state of ultrasound training in United States rheumatology fellowships. Arthritis Care Res. 2023;75(11):2245–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.25120.

Powers B, Smith CD, Arroyo N, Francis DO, Fernandes-Taylor S. How do academic otolaryngologists decide to implement new procedures into practice? Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2022;167(2):253–61.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All four authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Horowitz, D.L., Mandelin, A.M., Tabechian, D. et al. Precision Medicine in Rheumatology: The Promise of Ultrasound-Guided Synovial Biopsy, Barriers to Its Implementation in the United States, and Proposed Solutions. Curr Rheumatol Rep 26, 197–203 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-024-01138-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-024-01138-9