Abstract

Purpose of Review

This paper presents OPTIC as a framework to guide the conceptualization and implementation of telebehavioral health (TBH) in a comprehensive, structured, and accessible manner.

Recent Findings

There is a need for comprehensive frameworks for TBH implementation, yet current models and frameworks described in the literature have limitations. Many studies highlight favorable outcomes of TBH during COVID-19, along with increased adoption. However, despite the plethora of publications on general telehealth implementation, knowledge is disparate, inconsistent, not comprehensive, and not TBH-specific.

Summary

The framework incorporates five components: Originating site, Patient population, Teleclinician, Information and communication technologies, and Cultural and regulatory context. These components, abbreviated using the acronym OPTIC, are discussed, with examples of implementation considerations under each component throughout the project cycle. The value and larger implications of OPTIC are discussed as a foundation for stakeholders involved with TBH, in addition to key performance indicators, and considerations for quality enhancement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Telebehavioral health (TBH), defined as the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) to deliver behavioral health services (BHS) remotely [1], experienced gradual expansion in the decade prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. This expansion was driven by shortages and uneven distributions of behavioral health (BH) clinicians, increased connectivity and comfort with technology, and a growing body of research demonstrating its effectiveness, feasibility, and cost effectiveness [2]. TBH experienced exponential growth with the COVID-19 pandemic [3], during which there was an increase in reported BH conditions and symptoms, coupled with significant disruptions to BHS delivery and unmet BH care needs [4]. This combination of factors cemented TBH as a critical and integral approach for delivering BHS and mitigating certain access challenges during the pandemic [5]. For example, there was a 32-fold increase in Medicare Fee for Service Part B TBH visits in 2020 compared to 2019 [6]. In addition to the quantitative growth in TBH utilization, there has been a diversification of TBH delivery, including the use of both synchronous and asynchronous approaches, video, audio, text-based interventions, and mobile health applications [7, 8]. This has been supported and facilitated by regulatory changes, as well as reimbursement expansions, largely related to the pandemic. For instance, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has eliminated many restrictions regarding the locations where TBH can be delivered, and they expanded coverage to audio only and some asynchronous BHS [9].

With TBH expansion, the past 3 years also witnessed a surge of peer-reviewed articles, reports, guidelines, press releases, policy papers, and others, indicating increased interest in TBH among professional and academic communities. For instance, several publications demonstrated positive clinical and non-clinical outcomes associated with transitioning services to TBH during the pandemic [10]. The need for conceptual frameworks and holistic implementation models as necessary guides to enable developments in the field of TBH has long been recognized [11, 12]. Yet, despite the increasing literature prior to, and since the pandemic, many publications have approached TBH through scattered, non-standardized, theoretical, or non-holistic frameworks [13].

While providing a comprehensive overview of the literature on implementation and evaluation frameworks and models for telehealth is beyond the scope of this paper, there have been several relevant proposed implementation and evaluation frameworks since 2001, some of which are listed in this paper in Table 1. The latter were identified through a rapid literature search using key terms relevant to this work including implementation, framework, concept theory, model, telebehavioral health, digital health, and mental health, and then their data are extracted into Table 1. From those papers, multiple publications outlined systematic approaches to implementing telehealth services within healthcare systems, describing operational infrastructure elements, outlining evaluation approaches to telehealth implementation, and recommending core competencies, processes, and other components [14•]. However, many of these publications have not focused on TBH specifically [12, 14•]. And while there are established guidelines and best practices for delivering TBH services, offering clinical, technological, and regulatory guidance [15,16,17,18], to the best of our knowledge, they do not offer a unified, holistic, and practical framework for TBH program implementation. The literature provides many examples of general telehealth implementations using different approaches for conceptualizing them, at times using particular frameworks or models borrowed from other health-related and research fields [19,20,21]. While some have a TBH focus, others discuss telehealth implementation more generally [12, 14•, 22]. Different implementation and evaluation frameworks can be considerably overlapping, use terms interchangeably, or address a limited range of telehealth implementation topics, such as barriers and success factors associated with an implementation phase, as well as policy, behavioral, technological, ethical, and economic considerations [12]. TBH implementation and sustainability are described as shaped by a range of factors, including infrastructure, clinician and administrative involvement, technologies, institutional support, and funding [23]. Interestingly, these factors have historically been discussed in the literature as barriers to implementation, with several authors citing behavioral, organizational, technical, economic, and legal barriers [12, 23, 24].

That said, the following examples of telehealth frameworks were selected to highlight the ongoing need for such an implementation framework focused specifically on TBH:

Hebert [25] proposed a telehealth evaluation framework, based on the Donabenian’s approach of assessing quality of care, that examines structural and outcome variables separately, either as individual and organizational measures. Despite the advantage of building on a well-established approach, the proposed framework did not directly address the direct interaction or interconnectedness between individual and organizational measures, collapses patients and clinicians into one category, and does not sufficiently focus on ICT. Chang [20] proposed a conceptual monitoring and evaluation framework for telemedicine that incorporated a range of components of ICT, clinician and patient satisfaction, cost, quality, and data security. Despite the value and comprehensive nature of the framework, it is intended as a monitoring and evaluation framework for telehealth service implementation, rather than a TBH implementation framework. Edmunds et al. [26] proposed a telehealth model that centered primarily on telehealth practice in relation to policy and regulatory issues. Their work focused on informing policy makers and other stakeholders on telehealth, including barriers to implementation, risk management, technology-related considerations, among others. Despite the value of this publication, the authors did not give much insight on implementation-related guidelines and practical recommendations as part of their framework but rather listed major components to consider in telehealth practice. Lokken et al. [14•] described a systematic approach to effectively implement telemedicine in a large multicenter integrated healthcare system. The approach is comprehensive, covering a range of operational components, such as staffing infrastructure, functional partnerships, standardized processes and protocols, data analytics, and performance reporting, to name a few. The approach is sophisticated and broad, yet it is likely difficult to implement within less resourced, smaller healthcare systems, particularly behavioral health facilities that tend to struggle with the type of infrastructure, funding, and other resources that would be needed for such a systematic approach to implementation. Rangachari et al. [27] presented a narrative review of the literature on telehealth across six medical specialties. Three had lower telehealth utilization (gastroenterology, allergy-immunology, family medicine), and three had higher telehealth utilization (radiology, psychiatry, cardiology). Rangachari presented a conceptual framework that incorporated factors, both facilitators and barriers, categorized by the macro (policy), meso (organizational), and micro (individual) levels. This valuable framework tackles interrelationships between factors at these different levels, yet the approach to the discussion is comparative among the different medical specialties rather than focused specifically on TBH implementation.

Having a comprehensive and accessible framework can facilitate the manner in which TBH practices and programs are conceptualized, planned, and implemented. In a previous publication, Mahmoud et al. [23] discussed a TBH implementation model highlighting critical steps and considerations for planning, implementation, and evaluation. In doing so, the authors highlighted four major components of TBH programs, under which the implementation steps and considerations were grouped: originating site, patient population, teleclinician, and information and communication technologies. In addition, the authors discussed the value of aligning these components, possibly through a TBH organization that would serve as a facilitator or enabler for implementation [23]. In a subsequent publication, the authors incorporated a fifth component, the cultural and regulatory context, proposing a more comprehensive framework for TBH program implementation, referred to as the acronym “OPTIC” [28]. In this paper, the authors present OPTIC, building on previous literature along with the authors’ decade-long experience in designing and implementing TBH programs. The authors discuss OPTIC as a conceptual framework for TBH implementation within an expanding and increasingly more diversified digital healthcare ecosystem.

The OPTIC Framework

In this section, we present OPTIC in more detail, solidifying the discussion on its different components, and providing examples of how implementation steps and considerations can be conceptualized through this framework. While OPTIC is a framework, as opposed to an implementation model, because all TBH programs undergo a number of phases in their implementation, the examples are presented in alignment with the project lifecycle, including (a) assessment, (b) planning, (c) deployment, (d) evaluation, and (e) sustained operation (See Table 2).

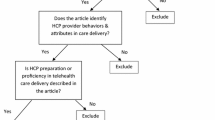

OPTIC is meant to serve as a practical framework to conceptualize key components of TBH programs. Despite the diversification of TBH care delivery approaches, utilizing different technologies, communication modalities, and approaches to care delivery, OPTIC maintains that TBH programs can be conceptualized through five components: Originating site, Patient population, Teleclinician, Information and communication technologies, and Cultural and regulatory context [19] (See Fig. 1).

-

Originating Site (OS): The physical location where the patient is located when TBH services are delivered. This can include hospitals, physician offices, federally qualified health centers, community mental health centers, and patients’ homes, among others [28].

-

Patient Population: The beneficiaries or beneficiary population who would receive TBH services at the OS. This may include the general population or an identified targeted subpopulation, which would be served by the TBH program [28].

-

Teleclinician: The clinician delivering treatment via TBH. Also known as “distant site practitioners,” these clinicians can include psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, social workers and psychologists, among others [29].

-

Information and communication technologies: The software, hardware and connectivity necessary to deliver and receive TBH services [30]. Examples can include different communication platforms, web-based and phone-based applications, e-prescribing systems, electronic health records (EHR), internet connectivity, and devices used to access and utilize such systems [23, 30].

-

Cultural and regulatory context: The cultural factors and regulatory landscape that influence the development and implementation of the TBH program. The cultural context can shape the delivery and experience of TBH services and has become increasingly central to TBH given the diversity of patient populations that can be served remotely. Regulatory factors can include local and federal laws, prescribing regulations, reimbursement policies and clinical guidelines that shape the TBH delivery [28].

Originating Site

The assessment phase of implementation ideally starts with conducting a needs assessment of the OS, including location, clinical settings, treatment modalities, existing and anticipated workflows [30], services to be delivered, organizational culture, and staff attitudes. This also includes assessing the geographic distribution and accessibility considerations for patients [13, 25, 31]. Such assessment is vital, as resources, other clinical supports, cultures, and regulations tend to vary by location of OS. Technological and connectivity needs for the TBH program must be identified, and software and equipment must be evaluated for compatibility and possible upgrade needs [20, 21, 25, 32]. Furthermore, OS staffing has been extensively highlighted in the literature as an important component of the pre-deployment phase. This includes identification of key staff [14•], understanding staff’s attitudes and willingness to receive training and share knowledge [31], identification of training needs, and designing such training [14•, 20, 21]. In addition, funding, resources, cost of services, and reimbursement must be considered.

The need for designing and implementing defined workflows, including for crisis management, with clearly identified roles and responsibilities at the OS, has been extensively outlined in the literature as one of the critical factors in the success of TBH implementation [20, 25, 31, 33]. It is important to involve senior clinical leadership in the design of such processes, including for scheduling, patient navigation, and session completion. This may facilitate the implementation of early processes necessary for care delivery, including relevant credentialing and privileging for the teleclinician and new workflows that would have to be implemented to support TBH delivery. OS staff should receive regular training on TBH, program workflows, and ICT [23], incorporating regulatory and cultural factors that shape TBH program delivery [33]. The pre-deployment phase also includes identifying a range of OS outcome measures and their tracking mechanisms, including those related to sustainability of the TBH program (operationally and financially), patient and staff satisfaction, utilization rates, wait times, and technology performance. Other outcome measures reported in the literature include number of patients served, session length, scheduling, OS environment and setting, availability of resources, cost-effectiveness, and affordability [13, 20, 24, 25].

Establishing a reporting system for monitoring and evaluation of the OS operations can provide valuable information for refining and improving BHS at the OS post-deployment [14•]. Examples include tracking the quality of services, collaborative work between OS staff and teleclinician [13], and the presence or adherence to standardized processes and workflows that are formalized into standard operating procedures (SOPs) [14•]. To support sustained operations and ensure minimal service disruption, ongoing OS staff training on compliance, ICT, cybersecurity, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and regulatory changes is needed, including regular review of practice and quality standards, risk management, and privacy protection protocols [21]. Data collected during evaluation can also help guide approaches to improve not only the quality of BHS but also operational efficiency and cost-efficiency.

Patient Population

TBH programs should be patient-centered, focused on meeting the needs of the patient population and effectively facilitating patient engagement and participation. The pre-deployment phase must identify the patient population’s needs [25], the accessibility of the OS, acceptability of the use of ICT for BHS delivery, as well as willingness to engage in treatment. Patient demographics, disease characteristics, linguistic and cultural considerations, treatment needs, user habits, ICT literacy, and payer composition of the patient population must also be reviewed [20, 23, 31]. This information enables the development and dissemination of patient-friendly educational resources about the TBH program, types of services, ICT used, therapeutic framework, and emergency protocols, in order to facilitate patient adoption of TBH services during deployment [13, 23, 31].

Post-deployment, data on patient outcomes, both clinical and nonclinical, should be tracked and analyzed to provide data-informed modifications to TBH programs to better serve patients [21, 34]. A range of outcome measures may be used, including patient satisfaction [13, 20], which may incorporate multiple factors, such as satisfaction with the care process, interactions with the teleclinician, and overall experience using TBH [25]. Other outcome measures include engagement in treatment, adherence to treatment, response to treatment as assessed through self-reports or standardized measurement scales, utilization of emergency rooms and higher levels of care [13], perceived quality of life, adverse effects, and functional status after receiving treatment [25]. These operational and clinical data points should guide further refinement of the TBH services to meet patient needs and improve outcomes.

Teleclinician

The teleclinician must have necessary educational credentials, licensure, and certification required to deliver BHS, in a manner that complies with federal and local regulations [23]. A range of other teleclinician-related factors should be considered pre-deployment during the recruitment and onboarding process, including an assessment of the teleclinician attitude, knowledge, and experience with TBH. Some areas of particular focus include assessing the teleclinician’s perceptions on the usefulness, effectiveness, and ease of use of ICT for TBH [1]. Related to these areas are the teleclinician’s willingness to receive training on, adapt to, and share knowledge about TBH [25, 31]. Other pre-deployment factors include assessing cultural competency, which would help guide training on culturally affirming care [23]. Training must also cover ICT, HIPAA-compliance, cybersecurity, clinical workflows, and remote emergency management [23, 25, 35].

Post deployment, a range of data points can be evaluated including teleclinician productivity and the quality of care, which can be assessed using a combination of audits, peer reviews, OS staff feedback, and patient feedback [13, 23]. Teleclinician satisfaction with TBH and with the degree of support from and engagement with the OS should also be tracked [23, 24]. Ongoing TBH service delivery requires ensuring appropriate and up-to-date licensure, certification, privileging, and credentialing; in addition, regular trainings are needed to ensure teleclinician and OS staff competencies on regulatory compliance, ICT, cybersecurity, HIPAA, cultural competency, evidence-based guidelines, ethical practice, and clinical workflows [21].

Information and Communication Technologies

ICT needs and resources should be assessed pre-deployment. Depending on the needs of the patient population, the types and modality of services to be provided, and the capacities of the OS and teleclinician, the technology needs may vary. The hardware required for TBH may range from personal smartphone devices to laptops with built-in cameras, other computers, external cameras, microphones, monitors, speakers, and servers [21, 32, 36••]. Similarly, software needs may include videoconferencing capabilities, EHR, electronic prescribing (e-prescribing) software, and smartphone applications [21, 32, 36••].

Regardless of the type TBH services and manner of delivery, ICT should be evaluated to ensure it meets ethical, privacy, security, and legal requirements [21, 36••] and that they are appropriate for the patient population [36••]. This includes identifying needs for adding, modifying, or upgrading ICT, including for hardware, software, and connectivity, along with training needs for OS staff, technicians, and patients [20]. Pre-testing of equipment, software, and connectivity [37] should be conducted as these pre-deployment considerations are critical to ensure smooth deployment following careful and tailored planning.

Once the ICT needs have been identified and evaluated, SOPs for accessing and using ICT for service provision should be documented and made accessible to OS staff and teleclinicians, including procedures and contingencies for breakdowns or failures in any of the aforementioned ICT elements [33]. For example, SOPs can be developed for when a videoconferencing session cannot be completed due to technological or connectivity issues, including troubleshooting attempts or switching to audio-only phone sessions [21]. Similarly, contingency plans should be developed for documenting and prescribing, should the EHR or e-prescribing system fail. Individuals responsible for ongoing maintenance and support of ICT should be identified pre-deployment, as they will provide support for and regular testing of ICT post-deployment [29].

As with other aspects of the OPTIC framework, ongoing monitoring of ICT, including for quality of sessions, connectivity, hardware, software, cybersecurity, and technological difficulties, is helpful in further refining the program [13, 21, 23, 25]. In addition, as newer technologies shape the delivery of TBH, training teleclinicians, OS staff, and patients on newer ICT or modalities of care delivery will be needed.

Cultural and Regulatory Context

Providing culturally affirming care in BH has been recognized as an important factor, especially for TBH, where the teleclinician and patients may not belong to or reside in the same community. It is crucial to ensure cultural competence of both the OS staff and teleclinicians. This includes paying close attention to diverse needs and characteristics of the patient populations served, including patients who identify as sexual or gender minorities, ethnic minorities, migrants, refugees, people living with disabilities, and linguistic minorities. Considerations for particular patient subgroups can prompt tailored approaches not only at the level of care delivery by the teleclinician only but also at the level of the OS as the setting where BHS are received, be it in terms of using culturally affirming language, inclusive and welcoming signs, interpreting services, user-friendly ICT, and others [8, 29, 32].

In the deployment phase, training should be provided to OS staff and teleclinician on different sensitivities of populations interfacing with TBH. While several training approaches have been employed, the fifth edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) offers a cultural formulation interview, which includes an updated understanding of gender identity issues and racial bias [38, 39]. Important cultural considerations include concepts such as cultural humility which emphasizes adopting an open stance towards cultural identity between clinicians and patients in order to minimize the gap in power dynamics between them. A teleclinician using cultural humility can grasp the limitations of not fully understanding a patient’s culture and addresses the limitation by considering the patient’s view of the most pertinent cultural factors by using patient-centered interviewing [39]. In addition, a culturally affirming approach to TBH care appreciates that patients may have varying attitudes towards both BH and ICT that may impact a patient’s receptivity towards TBH [32]. Post-deployment, it is important to conduct ongoing monitoring of the degree to which the care being provided is culturally affirming, through patient surveys or OS staff feedback [13].

From a regulatory standpoint, local and federal laws governing the delivery of TBH should be reviewed, including scope of practice, e-prescribing, reimbursement, privacy, and security [18, 29]. While local regulations may vary significantly, examples of federal regulations include the Ryan Haight Act, Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH), and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) [21]. It is important to also be mindful of reimbursement policies which can vary by jurisdiction, payer, type of OS, type of service, specialty, and modality of care delivery [40]. A robust assessment of these factors can enhance compliance, identify training needs for OS staff and teleclinician, and guide billing practices that support the cost-efficiency and sustainability of the TBH program [13]. Ongoing monitoring of regulatory and reimbursement guidelines, and related education of the teleclinician and OS staff, is necessary as the COVID-19 pandemic; the subsequent public health emergency, and the end of the state of emergency, has brought about significant and ongoing changes to regulations guiding the delivery of TBH, e-prescribing, and reimbursement policies [10].

OPTIC and Beyond

OPTIC provides a framework to guide the implementation of a singular TBH program. However, TBH programs should also consider where they fit within an increasingly diverse digital health ecosystem, looking beyond the particular solutions or services they are delivering. This means considering the degree to which TBH programs are integrated across the array of other healthcare services, how they are supporting health equity, and the degree to which they can be considered innovative. While not presented as a separate component of the OPTIC implementation framework, the value of integration within TBH has been recognized for several years [35], with the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and American College of Physicians supporting integrated approaches to telehealth implementation [29, 41]. As TBH continues to expand and diversify, TBH programs that deliver siloed point solutions will have limitations with regards to scaling in an integrated manner within a healthcare system challenged with fragmentation. Rather, TBH programs must be developed to integrate within the existing digital health ecosystem they are to be implemented in, to avoid creating unnecessary siloes that create inefficiencies and perpetuate fragmentation. This requires consideration for where the program lies along the patient care journey, how it interfaces across specialties and treatment modalities, and how it incorporates care coordination and referral pathways to the other solutions within the ecosystem. In addition, supporting health equity for the increasingly diverse patient populations served through TBH necessitates examining how the TBH program addresses patient needs, such as those shaped by cultural, sexual, gender, linguistic, racial, geographical, or socioeconomic factors, or other social determinants of health (SDOH) specificities.

TBH programs need to consider the degree to which they are delivering truly innovative clinical models to expand access to care, in a manner that mitigates the provider shortage and that meets patients’ needs and preference of how to access care, be it through the incorporation of different technologies or clinical delivery models. When it comes to innovation, the use of technology in healthcare is no longer sufficient for a program to be considered innovative. This is because the diversification in healthcare delivery post-COVID-19 created opportunities for convergence and hybridization in a manner that meets patients’ needs, through combinations of in-person and remote care, video with audio, and synchronous with asynchronous care. In fact, APA predicts that future psychiatric practices will likely deliver a hybrid model: in-person, video, and audio visits [42]. Moving forward, innovative TBH models will likely incorporate a combination of different ICT, delivering both synchronously and asynchronously, using newer clinical models to deliver a range of direct and consultative care, and incorporating collaborations between different clinicians, peer support specialists, care navigators, and case managers.

Conclusions

Despite the value of the different implementation components, models, and frameworks described in the literature, there is strong utility in proposing a framework such as OPTIC to guide the conceptualization and implementation of TBH programs in a manner that is comprehensive, practical, and accessible. The literature provides examples of TBH implementation that cover different components that are included in the OPTIC framework [21, 36••]. However, examples of implementation tend to be presented in isolation versus comprehensively. At a time of diversification, hybridization, and further innovation within TBH, the OPTIC framework can offer a standardized approach to the design, implementation, and evaluation of TBH programs. OPTIC provides a structured conceptual framework that is comprehensive and accessible, using the five core elements of OS, Patient Population, Teleclincian, ICT, and Cultural and Regulatory Context. OPTIC simultaneously defines the key components of a TBH program while allowing for a customizable approach to the operationalization of said elements, with each component being considered at various stages of implementation. Incorporating all five core components ensures all key aspects of a TBH program are considered. Given the scarcity of such frameworks in the literature as discussed above, OPTIC bridges a significant gap and provides an important tool to further develop this field from a practice and research angle.

In addition to guiding the planning and deployment of TBH, this framework is useful in identifying and monitoring TBH program outcomes, using key performance indicators categorized by OPTIC components. From a research lens, OPTIC can guide data collection for TBH programs using a standardized conceptual framework, support comparability of findings across multiple settings and contexts, and facilitate further understanding of TBH program implementation. Importantly, while OPTIC was developed with support from literature and the authors’ experiences in implementing TBH programs, this framework can be replicated and utilized within other telehealth programs beyond BH.

As we continue to refine TBH program implementation, it is important to recognize that there has been a paradigm shift in the conversation about TBH. Less than a decade ago, we were advocating for TBH acceptance while discussing evidence of effectiveness, feasibility, and potential for scalability. Post-COVID-19, it is a positive sign that the discussion has evolved to focus more on best practices in implementation including on how to use the technologies inherent to the delivery of remote care in order to enhance implementation, support quality, decrease costs, enhance integration, and ultimately improve outcomes.

Data Availability

No primary data was collected for the purposes of this study. The data is secondary and was extracted from the sources listed in this manuscript. The raw data files can be made available by contacting the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Mahmoud H, Vogt EL, Sers M, Fattal O, Ballout S. Overcoming barriers to larger-scale adoption of telepsychiatry. Psychiatric Annals. Slack Incorporated; 2019;49:82–8.

Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, Yellowlees PM. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed e-Health. 2013;19(6):444–54.

Garfan S, Alamoodi AH, Zaidan BB, Al-Zobbi M, Hamid RA, Alwan JK, et al. Telehealth utilization during the Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Comput Biol Med. Elsevier Ltd; 2021;138.

Vahratian A, Blumberg SJ, Terlizzi EP, Schiller JS. Morbidity and mortality weekly report symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder and use of mental health care among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic-United States [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products.html.

Whaibeh E, Mahmoud H, Naal H. Telemental health in the context of a pandemic: the COVID-19 experience. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2020;7(2):198–202.

Samson L, Tarazi W, Turrini G, Sheingold S. Medicare beneficiaries’ use of telehealth in 2020: trends by beneficiary characteristics and location. 2020.

Lattie EG, Stiles-Shields C, Graham AK. An overview of and recommendations for more accessible digital mental health services. Nat Rev Psychol. 2022;1(2):87–100.

Whaibeh E, Vogt EL, Mahmoud H. Addressing the behavioral health needs of sexual and gender minorities during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the expanding role of digital health technologies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. Springer; 2022;24:387–97.

HHS. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/telehealth-policy/policy-changes-after-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency. 2023. Telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 public health emergency.

Mahmoud H, Naal H, Whaibeh E, Smith A. Telehealth-based delivery of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder: a critical review of recent developments. Curr Psychiatry Rep. Springer; 2022;24:375–86.

Mohr DC, Richardson E. Telemental health: reflections on how to move the field forward.

van Dyk L. A review of telehealth service implementation frameworks. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(2):1279–98.

Haidous M, Tawil M, Naal H, Mahmoud H. A review of evaluation approaches for telemental health programs. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 2021;25:195–205.

• Lokken TG, Blegen RN, Hoff MD, Demaerschalk BM. Overview for implementation of telemedicine services in a large integrated multispecialty health care system. Telemed e-Health. 2019;00(00):1–6. While not BH specific, this publication outlines a systematic approach to delivering telehealth within a large integrated healthcare system. emphasis on infrastructure, standardized process, monitoring systems, and data analytics.

APA. American Psychiatric Association. 2018. APA and ATA Release New Telemental Health Guide.

Turvey C, Coleman M, Dennison O, Drude K, Goldenson M, Hirsch P, et al. ATA practice guidelines for video-based online mental health services. Telemed e-Health. 2013;19:722–30.

ATA. Core operational guidelines for telehealth services involving provider-patient interactions. 2018.

ATA. Practice guidelines for video-based online mental health services. 2013.

Khoja S, Durrani H, Scott RE, Sajwani A, Piryani U. Conceptual framework for development of comprehensive e-health evaluation tool. Telemed e-Health. 2013;19(1):48–53.

Chang H. Evaluation framework for telemedicine using the logical framework approach and a fishbone diagram. Healthcare Informatics Research. Korean Society of Medical Informatics. 2015;21:230–8.

Maheu MM, Drude KP, Hertlein KM, Lipschutz R, Wall K, Hilty DM. An interprofessional framework for telebehavioral health competencies. J Technol Behav Sci. 2017;2(3–4):190–210.

Haddad TC, Blegen RN, Prigge JE, Cox DL, Anthony GS, Leak MA, et al. A scalable framework for telehealth: the Mayo Clinic Center for Connected Care Response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemedicine Reports. Mary Ann Liebert Inc.; 2021;2:78–87.

Mahmoud H, Whaibeh E, Mitchell B. Ensuring successful telepsychiatry program implementation: critical components and considerations. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2020;7(2):186–97.

Garcia R, Adelakun O. A conceptual framework and pilot study for examining telemedicine satisfaction research. J Med Syst. 2019;43(3).

Hebert M. Telehealth success: evaluation framework development. Studies in health technology and informatics. 2001.

Edmunds M, Tuckson R, Lewis J, Atchinson B, Rheuban K, Fanberg H, et al. An emergent research and policy framework for telehealth. eGEMs (Generating Evidence & Methods to improve patient outcomes). 2017;5(2):1.

Rangachari P, Mushiana SS, Herbert K. A narrative review of factors historically influencing telehealth use across six medical specialties in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. MDPI; 2021;18.

Mahmoud H, Naal H, Whaibeh E, editors. Essentials of telebehavioral health. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022.

Shore JH, Yellowlees P, Caudill R, Johnston B, Turvey C, Mishkind M, et al. Best practices in videoconferencing-based telemental health April 2018. Telemed e-Health. 2018;24(11):827–32.

Mishkind MC. Establishing telemental heath services from conceptualization to powering up. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2019;42(4).

Chowdhury A, Hafeez-Baig A, Gururajan R, Chakraborty S. Conceptual framework for telehealth adoption in Indian healthcare. 2019.

Hilty DM, Maheu MM, Drude KP, Hertlein KM, Wall K, Long RP, et al. Telebehavioral health, telemental health, e-therapy and e-health competencies: the need for an interprofessional framework. J Technol Behav Sci. Springer; 2017;2:171–89.

Mahmoud H, Naal H, Cerda S. Planning and implementing telepsychiatry in a community mental health setting: a case study report. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(1):35–41.

Waqas A, Rehman A, Malik A, Aftab R, Allah Yar A, Allah Yar A, et al. Exploring the association of ego defense mechanisms with problematic internet use in a Pakistani medical school. Psychiatry Res [Internet]. 2016;243:463–8. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2016-43877-072&site=ehost-live.

Reynolds J, Griffiths KM, Cunningham JA, Bennett K, Bennett A. Clinical practice models for the use of e-mental health resources in primary health care by health professionals and peer workers: a conceptual framework. JMIR Ment Health. 2015;2(1):e6.

•• Hilty DM, Chan S, Torous J, Luo J, Boland RJ. A telehealth framework for mobile health, smartphones, and apps: competencies, training, and faculty development. J Technol Behav Sci. 2019;4(2):106–23. Discusses the knowledge, skills, and attitudes, as well as further training for clinicians in the use of increasingly diverse uses of technologies within healthcare.

ATA. Practice guidelines for video-based online mental health services. USA; 2013.

Moran M. Impact of culture, race, social determinants reflected throughout new DSM-5-TR. Psychiatr News. 2022;57(3).

Trinh NH, Tuchman S, Chen J, Chang T, Yeung A. Cultural humility and the practice of consultation-liaison psychiatry. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(4):313–20.

HHS. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/billing-and-reimbursement/medicare-payment-policies. 2023. Medicare payment policies.

Daniel H, Sulmasy LS. Policy recommendations to guide the use of telemedicine in primary care settings: an American College of Physicians Position Paper. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10).

APA. After the pandemic: what will the new normal be in psychiatry. 2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahmoud, H., Naal, H., Mitchell, B. et al. Presenting a Framework for Telebehavioral Health Implementation. Curr Psychiatry Rep 25, 825–837 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-023-01470-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-023-01470-4