Abstract

Purpose of Review

School mental health services have achieved recognition for increased access to care and intervention completion rates. While best practice recommendations include connection of school mental health programming to multi-tiered systems of support that promote early identification and intervention, many schools struggle to operationalize student screening for trauma exposure, trauma symptoms, and service identification. Relatedly, progress monitoring for trauma symptoms, and the effect of trauma on school functioning in the context of catastrophic events, can also be difficult to systematically collect.

Recent Findings

Research regarding the effects of catastrophic events, such as exposure to natural disasters, terrorist attacks, war, or the journey to refugee status on children and youths school functioning, indicates salient age and gender differences among student responses. In addition, school professionals have been identified as sources of social support for students and as potential brokers to school linked intervention resources for children, youth, and their families.

Summary

Based on our review, we outline recommendations for school professionals, including potential changes to school policies and procedures, and delineate future research questions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

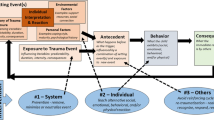

An estimated 1 in 5 students experiences inattention, impulsivity, depression, anxiety, or social withdrawal [1]. Taken together with calculations suggesting that less than half of the 18 million children and youth in need of mental health intervention achieve service receipt [2,3,4], comprehensive approaches to addressing mental health in schools continue to gain momentum both nationally and internationally [5]. Schools are uniquely positioned to provide convenient access to mental health interventions, reducing barriers that often interfere with treatment (e.g., transportation, health insurance [6,7];). Relatedly, when mental health concerns are addressed, increased academic performance can occur [8, 9], especially when these efforts are connected to a multi-tiered or systems-level approach. Multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) that systematically join positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS; a proactive, multi-tiered system that reduces behavior problems) and school mental health services (SMH) facilitate the identification of students experiencing academic, emotional, and behavioral barriers to success by providing promotion/prevention activities at tier 1, early intervention at tier 2, and intervention at tier 3 [10•, 11, 12].

Multi-tiered systems of support are strengthened when PBIS and school mental health services are joined through an interconnected systems framework [10•]. There is a growing emphasis on how to improve the identification of students experiencing internalizing problems, such as anxiety, depression, or symptoms of trauma through these interconnected systems [13•]. It is not uncommon for students experiencing trauma to achieve less visibility from school professionals than youth with overt behavior problems, such as impulsivity or aggression. Although trauma exposure can result in the manifestation of a variety of different symptoms, youth who respond to trauma through the development of internalizing symptoms such as anxiety or depression often go unnoticed [14], decreasing their likelihood for connection to targeted intervention supports. For this reason, guidelines relative to school-based trauma-informed care initiatives, their connection to MTSS [15••], and best practices for conducting trauma screening and intervention processes in schools [16••] have been developed and disseminated. While this guidance is foundational to operationalizing the work, further translation and testing of trauma-informed and responsive practices, and their connection to academic and school outcomes are needed, particularly in the context of catastrophic events.

The effects of catastrophic events, such as natural disasters, terrorism, war, and political conflict on children and youth’s school functioning, present with unique challenges (e.g., loss or prolonged separation from loved ones; repeated moves, school relocations, or lapses in time when school is not attended). These may require additional and specific considerations for both research and practice. Emerging evidence suggests the need for investigating the indirect effects of trauma on school functioning given that linkages between trauma exposure and academic difficulties are the function of post-traumatic stress symptoms, and not the direct effect of traumatic stress [17, 18]. For example, there is evidence indicating that symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (i.e., emotional numbing, hyperarousal) can serve as a mechanism through which trauma exposure contributes to school dissatisfaction in the wake of natural disasters [19], with school dissatisfaction as a known contributor to dropout [20] and potential target for intervention post-disaster. While the effects of natural disasters on school functioning have been more widely studied and offer applications for school professionals, other types of catastrophic events that affect academic and school functioning have been less widely studied. Examples of these less widely studied topic areas include the potential interplay among acculturative stress, trauma exposure, and academic or school functioning in immigrant or refugee youth [21••], a consistent or agreed upon definition of academic or school performance indicators to track recovery in youth exposed to catastrophe, and investigation of positive post-traumatic growth and its effects on school functioning. Thus, in the proceeding sections, we offer a brief review of current findings relative to the effects of terrorism, war, refugee status, and natural disasters on child and youth school functioning. In addition, we offer practical applications for identification, screening, and connection of students and their families relative to MTSS and provide directions for future research.

Child and Youth Survivors of Terrorist Attacks and War

Survivors of terrorist attacks often include children and youth [22], with schools identified as targets for these attacks because their locations are often easily accessible, typically unguarded, and provide opportunity for mass causalities [23]. In the wake of a single incident attack, many students will continue to struggle in school (e.g., declining grades, increased absences) up to 15 months after exposure. Youth survivors (N = 495; all heard gunshots during an attack that resulted in 69 fatalities with others injured) of a terrorist attack continued to report impaired academic performance at 4–5 (69%) and up to 14–15 (61%) months after the attack [24]. The effects of ongoing or prolonged exposure to war on children and youth can result in a markedly different pattern of symptomatology than an isolated terrorist attack; in that, during war, there is no differentiation between the front lines and the home front. High levels of trauma exposure during war do not necessarily result in high levels of post-traumatic stress. Emerging evidence indicates that when exposed to prolonged threats (e.g., a sample of youth subjected to high shelling in the geographic locations surrounding the Gaza strip), youth may not necessarily experience high levels of post-traumatic stress (PTS) or impairment. Interestingly, some researchers have theorized that living under continuous, ongoing threats may result in an adaptive process through which emotional habituation occurs, contributing to youth resiliency [25, 26].

Ongoing threats of terrorism or war can affect several areas of functioning. Often though, studies focus on the examination of single factor and its contribution to outcomes related to post-trauma adjustment, rather than considering or examining the simultaneous impact of multiple factors or the relationships among them [27, 28]. A less widely explored phenomenon among these survivors includes post-traumatic growth [29] and additional exploration regarding the factors influencing its development is warranted. Caregivers of adolescent survivors of terrorism report that their children show increased tenacity and self-discipline regarding school subjects, increased prosocial behavior, and interpersonal sensitivity through post-traumatic growth [29]. There may be multiple and related factors influencing the development and promotion of PTG, and identification of these factors and their impact on school functioning could result in targeted approaches for facilitating positive post-traumatic changes using an MTSS approach.

There are implications for research and practice regarding the intersection between these types of trauma exposures and school mental health, including the need for further exploration and definition of the factors promoting school functioning through MTSS. While little is known about how to best support students relative to their academic performance and well-being after a terrorist attack [22], there is evidence indicating that school connection can serve a critical role in mitigating the symptoms of post-traumatic stress, as youth survivors of terrorism reporting high levels of school connectedness (i.e., feeling accepted, respected, included, and supported at school [30]) experience fewer post-traumatic stress symptoms despite the use of emotion-focused coping strategies that typically exacerbate symptomatology (e.g., self-blame [31],). School professionals have also been identified as resources for students, reaching out to them during wartime school closures. When educators engage students in caring connections through social media, students report higher levels of emotional support [32, 33], which in turn can promote student resilience [34].

School mental health programming in countries recovering from long-term political conflict and war can also provide prospective blueprints for the implementation of MTSS in recovering communities. There have been laudable efforts regarding the potential for MTSS in countries such as Liberia, where citizens endured a 14-year civil war. Although this war ended a decade ago, the post-war healthcare system, while in its nascence, shows promising expansion relative to school mental health. Through support from non-governmental Organizations (NGOs), such as World Bank, mental health clinicians have recently deployed to school-based clinics. The Liberian Ministry of Health is convening a school mental health committee to support policy development regarding the implementation of effective selective and universal programs for addressing intervention needs in early childhood emotional and behavioral concerns, developmental disabilities, and substance use [5].

Child and Youth Refugees

Notably, refugees represent a diversity of cultures, nations, ethnicities and racial backgrounds. They leave their home countries due to fear of persecution based on their membership to a particular social or political group [35]. Data suggests that more than half of the refugees are under the age of 18 [36]. It is difficult to track this population of refugees as many do not have official identification documents and have also potentially experienced separation from their families as part of the preflight or resettlement processes. Children and youth survivors leave behind their homes and belongings due to combat or war, typically witnessing conflict prior and during departure, and then begin acculturation in a new country [37, 38].

Schools are often valued more than in other social services organizations by refugee families [39] and may be one of the few community agencies offering formal supports [40] that are non-stigmatizing and without cost-related barriers [41, 42]. However, navigating school contexts and academic learning can be especially difficult for students who become refugees during adolescence. It can take 4–7 years for children and youth to learn academic English, and up to a decade for those whose formal education has been interrupted [43]. Even then, students with English as a second language remain at a significant disadvantage, especially on timed national standardized exams (e.g., SAT, MCAT). Taken together with expectations to engage in more complex academic material and having less time in their host county’s school to master a new language, older youth may experience more challenges in school [44]. Additionally, based on their racial, ethnic, or religious background, children and youth may experience discrimination from peers and teachers when in school [45] and receive disproportionate disciplinary action as a result of these prejudices [46, 47].

School professionals may misinterpret trauma-related symptoms and behaviors presented by students [48, 49] particularly given that non-Western cultures may not differentiate emotional from physical health [50]. The effects of trauma often manifest through repeated complaints of headaches, stomachaches, or other somatic concerns [42, 48, 49]. Among trauma-exposed children and youth, the profile of clinic-referred refugee children and youth differs significantly from peers who have recently immigrated to the USA and from US-born peers. These differences include the total number of and type of trauma exposures (i.e., refugees reported more exposure loss, separation, bereavement, community violence, and forced displacement [51•]). These findings serve as invaluable practical informants to school-based interventions given evidence indicating that refugee students with more expansive trauma histories have been found to report more positive feelings about school than those with lesser exposures. While it is not clear what is driving the relationship among trauma exposure and feelings about school, it is plausible that the safety and structure that is offered through school contexts allows children to better cope with the negative experiences they had prior to resettlement [52]. Parental involvement can also result in the experience of fewer child and youth depressive symptoms during resettlement [52]. However, many refugee parents may be struggling with their own trauma exposures, potentially resulting in both physical and emotional impairments, and benefit from school-family-community outreach efforts that offer connections to intervention.

While culturally responsive school mental health approaches have been tested in refugee children and youth [50, 53••], best practices relative to promotion of school and academic success have been less widely explored in this population [21••] than in other trauma-exposed populations, potentially due to the recent and rapid growth in refugee populations [54]. Thus, researchers, educators, service providers, and policymakers have identified key topic areas for exploration in refugee children and youth relative to schools. The top four research questions include assessing the effectiveness of newcomer programs, the impact of family and community stressors outside of school on school functioning, teacher stresses relative to working with refugee students, and how schools can effectively engage this population [21••]. Relatedly, the designated role of educator and other school professionals in educational and mental health referrals, engagement of students and parents in school, and consultation process among this population warrants additional investigation. Further study regarding the feasibility and acceptability of these research priorities would support program development and effectiveness testing.

Child and Youth Survivors of Natural Disasters

It is estimated that for each year in this decade, around 175 million children will be exposed to natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, fires, floods, tsunamis, blizzards, droughts, and other extreme weather conditions [55]). Several studies have explored contextual factors influencing the impact of natural disasters on immediate mental health, to include prolonged displacement of children and youth survivors from homes, schools, and communities, personal losses, and relocation. In the wake of disaster, youth survivors have shown declines in academic performance and achievement [56, 57] and increases in suspensions and expulsions [58] with disaster-related trauma exposures contributing to patterns of emotional dysregulation resulting in aggressive behaviors [58, 59] and anxious emotions [18] that indirectly influence school and academic outcomes.

The long-term effects of disaster on children and youth suggest consideration of developmental differences when planning and implementing school-based post-disaster mental health programming. For example, younger students (ages 11–13) report lower levels of post-traumatic stress and depressive symptoms following disaster-related relocations than older students (ages 17–19), with the opposite being true for survivors who returned to their neighborhoods after Hurricane Katrina (i.e., older students who returned reported lower symptoms, and younger students higher symptoms [60],). There is also evidence suggesting that youth ages 12 and older with lower levels of perceived control (e.g., the ability to regulate their anxious emotion) will report higher levels of post-traumatic stress and anxiety in the wake of disaster [61]. Additionally, gender has been identified as moderator for post-disaster symptomatology, with negative associations between post-traumatic stress symptoms and self-reported competence/well-being levels shown as more problematic for girls than boys [62]. Taking this into consideration, interventions that target increased competence/well-being, especially among girls, could offer prophylactic effects in the wake of disaster [63].

Schools can further mitigate the effects of a disaster by offering trauma responsive intervention programming. Research suggests that in the wake of disaster, children will present with different trajectories: some with low stable symptom levels despite high trauma exposure, some with stable low symptom levels and low exposure, and some with stable high symptoms [64]. The resilient subgroup (e.g., low symptoms and high exposure) employed avoidant coping strategies (e.g., social withdrawal, wishful thinking, resignation, strategies of distraction) less frequently than the other two subgroups. Taking this into consideration, students may benefit from school-based interventions that mitigate post-disaster emotional dysregulation and increase social support among child and youth disaster survivors, particularly given students are more likely to complete trauma-focused treatments when they occur in school than other community settings [65]. This is consistent with policy recommendation from United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) use of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction [66], which implicates schools in addressing risk reduction and resilience education post-disaster. There are intervention packages, such as Supporting Students Exposed to Trauma (SSET), for children and youth ages 10–16, which targets skill building for healthy coping, relaxation, and increasing levels of peer and parent support [67], or Bounce Back, which is for children ages 5 to 11. Bounce Back covers the same topic areas as SSET but includes increased parental involvement components [68]. Journey of Hope [69], which is specifically for disaster survivors ages 8–11 and targets identification and coping of anxious, sad, and angry emotions, also shows promise. All three interventions connect with early intervention (tier 2) supports in schools.

Conclusions and Future Directions

There are common implications for MTSS among the different types of traumas discussed within this review. Children and youth may return to school without any records regarding their past academic performance, having experienced substantial losses, and in need of a diversity of concrete and emotional supports. Trauma-related responses, potentially misinterpreted as oppositionality, inattention, or poor motivation, can be triggered when classrooms are loud and crowded [70], and further interfere with the development of student-teacher relationships or school connectedness. School supports for trauma-exposed students need to go beyond curriculum requirements and are relevant to implementation of MTSS approaches for a few key reasons. Positive behavior supports, for example, focus upon behaviors that are directly observable. Student responses to trauma (e.g., increased absences or trips to the school nurse) may not present in the classroom as behaviors commonly monitored or observed in the classroom, resulting in poor visibility of these students to school professionals. Conducting routine screenings allow for monitoring of specific behavioral health concerns [71••], such as trauma. Yet, there are cautions against conducting universal trauma screenings in schools, which include discrepancies in agreement between child and parent report regarding exposure to adverse and traumatic events [72, 73], obtaining reliable and valid responses during the assessment process, and potential difficulties securing parental consent prior to conducting the assessment. There is a paucity of research delineating best practices for screening, assessment, and progress monitoring for trauma [15••, 16••]. This is an area in need of further exploration considering lifetime trauma exposure can affect children’s ability to recover from catastrophic events. For example, trauma history has been implicated as a stronger predictor of post-traumatic stress and depressive symptoms post-disaster than hurricane exposure alone [74]. For students in need of additional school supports, tracking trauma history and student responses to intervention could facilitate early identification, appropriate triage and connection to indicated intervention approaches (e.g., stepped care through Bounce Back/SSET, or more intensive interventions such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy), and progress toward behavioral and educational benchmarks.

As indicated through our review, testing and effectiveness trials in these topic areas are critical for child and youth survivors of catastrophe, not only for the development of best practices but for the development of an agenda that connects school policies, procedures, and trainings that support this work. Emerging digitized platforms, such as the SHAPE system, support ongoing monitoring and high-quality implementation of school-wide initiatives [5]. The SHAPE system shows promise, offering assessment and guidance relative to trauma responsive practices, such as maintaining calm and safe classrooms (tier 1), training all school professionals to share a common understanding of trauma and trauma-exposed students (tier 1), and developing partnerships with community partners specializing in evidence-based interventions for trauma (tiers 2 and 3 [75•]). In the wake of natural disasters, this school data system could be used to track student age and number of relocations. Review of age and relocation data could be used to identify students in potential need of trauma responsive screening and intervention. Relatedly, training school professionals (e.g., educators, school administrators) in student responses to trauma have been implicated in the identification of trauma-exposed students, their referral to services, and the success of trauma interventions [76]. Training packages, such as Kognito’s Trauma-Informed Practices for K-12 schools, have been deployed to increase educator knowledge and awareness of trauma-related stress levels [77]. Additional investigation is needed to determine whether this training package results in educator behavior change. Further testing of intervention packages that target student trauma (e.g., Bounce Back, SSET) in child and youth survivors of catastrophic events are also indicated. This group of survivors is heterogeneous in terms of the total number and types of traumas experienced [51•]. Exploration of these interventions and their influence on student coping styles, academic performance and achievement, school connectedness, and behavior are needed to assess potential long-term impacts on post-disaster school functioning.

Recommendations

As noted, MTSS offers different levels of support at tier 1 through primary prevention/promotion, at tier 2 through early intervention, and at tier 3 through intervention (Tier 3). Conducting trauma-related screening, assessment, and intervention may differ based upon the type of trauma that has occurred, exposures associated with that trauma, and the number of students affected by it. For example, a community-wide natural disaster may affect many students, resulting in increased referral of students to tier 2 supports (e.g., coping skills groups), whereas a student seeking asylum may benefit from an intensive, individualized assessment and intervention plan. At the school building level, there may be one team of school professionals (e.g., school psychologists, counselors, social workers, administrators; community mental health professionals) that meets to discuss MTSS planning, or three separate teams (e.g., a team that only plans for tier 1 [78]) that meet to plan services. These teams use school data to determine program selection and student movement across tiers [13•] and select assessment and intervention strategies that are within the school’s capacity to execute. Preliminary study indicates that a combination of supports, such as the Check in Check out (CICO [79];) intervention, which targets school engagement, and daily progress reports (DPR [79];), which are used to facilitate student coping skills such as deep breathing, is effective in supporting students struggling with emotional and behavioral problems related to trauma [13•]. The use of the CICO and DPR could be particularly impactful in the context of catastrophic events, with additional study including parental involvement in tiers 2 and 3 supports relative to trauma. The review of CICO and DPR at home by youth and their parents, for example, could be used to promote practice and generalization of skills, especially if connected to other school-based interventions, such as Bounce Back, SSET, or Journey of Hope. Additionally, it could promote the generalization of skills across multiple contexts (e.g., at home or during extracurricular activities).

Parental involvement is not usually targeted unless more intensive student supports are needed through tiers 2 or 3 [80]. However, integrating and introducing culturally responsive strategies at tier 1 would allow for scaffolding of parental involvement and for more efficient student connection to tier 2 and 3 supports. For schools, the identification of community-based clinicians with cultural knowledge and training in trauma-focused intervention is critical. Having these clinicians serve as school consultants or as permanent MTSS team members would provide a mechanism by which school professionals could achieve potential access to training in relevant cultural values and norms prior to meetings with families, increased understanding of culturally relevant emotional vocabulary connected to the trauma [50], and increased ability to provide assistance in responsive outreach for trauma-focused treatments.

Finally, school policies that include guidelines for how educators and other school professionals can maintain contact with their students during catastrophic events should be considered. This connection among school professionals, students, and in a tertiary way, their families can serve as a method for facilitating triage, resulting in increased understanding of student referral needs relative to intervention supports once the infrastructure is restored. By maintaining contact with youth during a catastrophe, school professionals can facilitate the identification of students in need of additional screening and assessment once schools re-open. In addition, school professionals can begin sharing what they have learned as major concerns from students and use this information to develop intervention plans. Developing school policies and preparing school professionals for use of communication protocols during catastrophe could further enhance long-term student recovery. Future studies could further assess the effect of these communications, and the application of information collected from them, on intervention strategies that target post-catastrophe school functioning.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017.

Costello EJ, Foley DL, Angold A. 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. II. Developmental epidemiology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:8–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000184929.41423.c0.

Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Alegría M, Costello EJ, Gruber MJ, Hoagwood K, et al. School mental health resources and adolescent mental health service use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:501–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.002.

Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:372–80. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160.

Weist MD, Bruns EJ, Whitaker K, Wei Y, Kutcher S, Larsen T, et al. School mental health promotion and intervention: experiences from four nations. Sch Psychol Int. 2017;38:343–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034317695379.

Pullmann MD, Weathers ES, Hensley S, Bruns EJ. Academic outcomes of an elementary school-based family support programme. Adv School Ment Health Promot. 2013;6:231–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2013.832007.

Pullmann MD, VanHooser S, Hoffman C, Heflinger CA. Barriers to and supports of family participation in a rural system of care for children with serious emotional problems. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46:211–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9208-5.

Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 2011;82:405–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x.

Walker SC, Kerns SEU, Lyon AR, Bruns EJ, Cosgrove TJ. Impact of school-based health center use on academic outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:251–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.07.002.

• Barrett S, Eber L, Weist MD. Advancing education effectiveness: an interconnected systems framework for Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and school mental health. Center for Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (funded by the Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education). Eugene: University of Oregon Press; 2013. This reference describes and operationalizes the Interconnected Systems Framework (ISF) which joins Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and School Mental Health (SMH) systems to improve educational outcomes for all children and youth, particularly for those at risk of developing mental health challenges. Examples from three different states are highlighted to provide guidance for this work at school building, district, and state levels.

Fazel M, Hoagwood K, Stephan S, Ford T. Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:377–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70312-8.

Stephan SH, Sugai G, Lever N, Connors E. Strategies for integrating mental health into schools via a multitiered system of support. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2015;24:211–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.12.002.

• Weist MD, Eber L, Horner R, Splett J, Putnam R, Barrett S, et al. Improving multitiered systems of support for students with “internalizing” emotional/behavioral problems. J Posit Behav Interv. 2018;20:172–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717753832. This reference provides case examples for improving screening and connection to intervention for depressed, anxious, and trauma-exposed students through application of the Interconnected Systems Framework (ISF) and includes detailed approaches for identification of students, selection of interventions, and data-based decision-making.

Weist MD, Myers CP, Hastings E, Ghuman H, Han YL. Psychosocial functioning of youth receiving mental health services in the schools versus community mental health. Community Ment Health J. 1999;35:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018700126364.

•• Chafouleas S, Johnson A, Overstreet S, Santos N. Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. Sch Ment Heal. 2016;8:144–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8. This reference provides recommendations for developing trauma-informed schools with emphasis on high-quality implementation, implications for professional development, and methods for evaluating impact.

•• Eklund K, Rossen E. Guidance for trauma screening in schools. Delmar: National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice; 2016. This reference illuminates logistical issues relative to trauma screening in schools, such as obtaining parental consent, conducting universal versus selected screenings, time commitment, and referral mechanisms for screening, and the need for understanding what to detect when screening (e.g., trauma exposure; symptoms of trauma exposure).

Saigh PA, Mroueh M, Bremner JD. Scholastic impairments among traumatized adolescents. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:429–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00111-8.

Weems CF, Scott BG, Taylor LK, Cannon MF, Romano DM, Perry AM. A theoretical model of continuity in anxiety and links to academic achievement in disaster-exposed school children. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25:729–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000138.

Sims A, Boasso A, Burch B, Naser S, Overstreet S. School dissatisfaction in a post-disaster environment: the mediating role of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Child Youth Care Forum. 2015;44:583–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-015-9316-z.

Bridgeland JM, Dilulio JJ, Morison KB. The silent epidemic: perspectives of high school dropouts. Civic Enterprises; 2006. Retrieved from http://www.civicenterprises.net/pdfs/thesilentepidemic3-06.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2019.

•• McNeely CA, Morland L, Doty SB, Meschke LL, Awad S, Husain A, et al. How schools can promote healthy development for newly arrived immigrant and refugee adolescents: Research priorities. J Sch Health. 2017;87:121–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12477. Key stakeholders in education were convened for identification of topic areas in need of additional exploration. These included evaluating newcomer programs (mean = 4.44, SD = .55), identifying how family and community stressors affect newly arrived immigrant and refugee adolescents' functioning in school, identifying teachers' major stressors in working with this population, and how to engage immigrant and refugee families in their children's education.

Stene LE, Schultz JH, Dyb G. Returning to school after a terror attack: a longitudinal study of school functioning and health in terror-exposed youth. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28:319–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1196-y.

Petkova EP, Martinez S, Schlegelmilch J, Redlener I. Schools and terrorism: global trends, impacts, and lessons for resilience. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 2017;40:701–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2016.1223979.

Strøm IF, Schultz J, Larsen T, Dyb G. School performance after experiencing trauma: a longitudinal study of school functioning in survivors of the Utøya shootings in 2011. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016;7:1. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.31359.

Shechory Bitton M, Laufer A. Children’s emotional and behavioral problems in the shadow of terrorism: the case of Israel. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;86:302–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.01.042.

Seery MD, Holman EA, Silver RC. Whatever does not kill us: cumulative lifetime adversity, vulnerability, and resilience. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99:1025–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021344.

Gargano L, Dechen T, Cone J, Stellman SD, Brackbill RM. Psychological distress in parents and school-functioning of adolescents: results from the world trade center registry. J Urban Health. 2017;94:597–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-017-0143-4.

Breslau J, Lane M, Sampson N, Kessler RC. Mental disorders and subsequent educational attainment in a US national sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:708–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.016.

Glad KA, Kilmer RP, Dyb G, Hafstad GS. Caregiver-reported positive changes in young survivors of a terrorist attack. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28:704–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1298-7.

Goodenow C. Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: relationships to motivation and achievement. J Early Adolesc. 1993;13:21–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431693013001002.

Moscardino U, Scrimin S, Capello F, Altoe G. Brief report: self-blame and PTSD symptoms in adolescents exposed to terrorism: is school connectedness a mediator? J Adolesc. 2014;37:47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.10.011.

Rosenberg H, Ophir Y, Asterhan CSC. A virtual safe zone: teachers supporting teenage student resilience through social media in times of war. Teach Teach Educ. 2018;73:35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.011.

Ophir Y, Rosenberg H, Asterhan C, Schwarz B. In times of war, adolescents do not fall silent: teacher-student social network communication in wartime. J Adolesc. 2016;46:98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.11.005.

Werner EE. Children and war: risk, resilience, and recovery. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24:553–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000156.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. Geneva: Author; 1951.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Statistical yearbook 2010, 10th edition: trends in displacement, protection and solutions. Geneva: Author; 2010.

Bronstein I, Montgomery P. Psychological distress in refugee children: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14:44–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0081-0.

Fazel M, Stein A. The mental health of refugee children. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:366–70. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.87.5.366.

Dutton J, Hek R, Hoggart L, Kohli R, Sales R. Supporting refugees in the inner city: an examination of the work of social services in meeting the settlement needs of refugees. London: Middlesex University and London Borough of Haringey; 2000.

Candappa M, Egharevba I. ’Extraordinary Childhoods’: the social lives of refugee children. Children 5–16 Research Briefing Number 5. Swindon: Economic and Social Research Council; 2000.

Beehler S, Birman D, Campbell R. The effectiveness of cultural adjustment and trauma services (CATS): generating practice-based evidence on a comprehensive, school-based mental health intervention for immigrant youth. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50:15–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9486-2.

Pumariega A, Rogers K, Rothe E. Culturally competent systems of care for children’s mental health: advances and challenges. Community Ment Health J. 2005;41:539–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-005-6360-4.

Thomas WP, Collier VP. A national study of school effectiveness for language minority students’ long-term academic achievement. Santa Cruz: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence, University of California-Santa Cruz; 2002. Retrieved from: http://www.thomasandcollier.com/assets/2002_thomas-and-collier_2002-final-report.pdf

Short DJ, Boyson BA. Helping newcomer students succeed in secondary schools and beyond. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics; 2012. Retrieved from: https://www.carnegie.org/media/filer_public/ff/fd/fffda48e-4211-44c5-b4ef-86e8b50929d6/ccny_report_2012_helping.pdf

Crosnoe R, Lopez Turley RN. K-12 educational outcomes of immigrant youth. Futur Child. 2011;21:129–52.

Skiba RJ, Horner RH, Chung CG, Rausch MK, May SL, Tobin T. Race is not neutral: a national investigation of African American and Latino disproportionality in school discipline. Sch Psychol Rev. 2011;40:85–107.

Swain-Bradway J, Loman SL, Vincent CG. Systematically addressing discipline disproportionality through the application of a school-wide framework. Multiple voices for ethnically diverse exceptional learners. Wilder Res. 2014;14:3–17. https://doi.org/10.5555/muvo.14.1.jl626n21408t4846.

Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Murray LA. Trauma-focused CBT for youth who experience ongoing trauma. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35:637–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.002.

Sullivan AL, Simonson GR. A systematic review of school-based social-emotional interventions for refugee and war-traumatized youth. Rev Educ Res. 2016;86:503–30.

Isakson BL, Legerski JP, Layne CM. Adapting and implementing evidence-based interventions for trauma-exposed refugee youth and families. J Contemp Psychother. 2015;45:245–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-015-9304-5.

• Betancourt TS, Newnham EA, Birman D, Lee R, Ellis BH, Layne CM. Comparing trauma exposure, mental health needs, and service utilization across clinical samples of refugee, immigrant, and U.S.-origin children. J Trauma Stress. 2017;30:209–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22186. To better understand and develop mental health services for trauma-exposed refugee children and adolescents, the authors assessed levels of trauma exposure, psychological distress, and mental health service utilization among refugee-origin, immigrant origin, and U.S.-origin children and youth. Compared with U.S.-origin youth, refugee youth had higher rates of community violence exposure, dissociative symptoms, traumatic grief, somatization, and phobic disorder.

Trentacosta CJ, McLear CM, Ziadni MS, Lumley MA, Arfken CL. Potentially traumatic events and mental health problems among children of Iraqi refugees: the roles of relationships with parents and feelings about school. Am J Orthop. 2016;86:384–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000186.

•• Franco D. Trauma without borders: the necessity for school-based interventions in treating unaccompanied refugee minors. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2018;35:551–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0552-6. This article describes migration trauma among Mexican and Central American unaccompanied refugee minors (URM), describing potential pre-migration, in-journey, and post-migration traumas. Clinical implications of culturally responsive and trauma-informed treatment of URM, a case example of clinical intervention, and the importance of bridging the gap between research and culturally responsive, trauma-informed interventions for URM in schools are discussed.

Tienda M, Hawkins R. Immigrant children: introducing the issue. Futur Child. 2011;21:3–18.

Legacy of disasters: the impact of climate change on children; save the children; 2007. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/3986/pdf/3986.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2019.

Lamb J, Gross S, Lewis M. The Hurricane Katrina effect on mathematics achievement in Mississippi. Sch Sci Math. 2013;113:80–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssm.12003.

Ward ME, Shelley K, Kaase K, Pane JF. Hurricane Katrina: a longitudinal study of the achievement and behavior of displaced students. J Educ Stud Placed Risk. 2008;13(2–3):297–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824660802350391.

Scott BG, Lapré GE, Marsee MA, Weems CF. Aggressive behavior and its associations with posttraumatic stress and academic achievement following a natural disaster. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43:43–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.807733.

Marsee MA. Reactive aggression and posttraumatic stress in adolescents affected by Hurricane Katrina. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:519–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802148152.

Hansel TC, Osofsky JD, Osofsky HJ, Friedrich P. The effect of long-term relocation on child and adolescent survivors of hurricane Katrina. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26:613–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21837.

Weems CF, Russell JD, Banks DM, Graham RA, Neill EL, Scott BG. Memories of traumatic events in childhood fade after experiencing similar less stressful events: results from two natural experiments. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2014;143:2046–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000016.

Masten AS, Osofsky JD. Disasters and their impact on child development: introduction to the special section. Child Dev. 2010;81:1029–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01452.x.

Weems CF, Osofsky JD, Osofsky HJ, King LS, Hansel TC, Russell JD. Three-year longitudinal study of perceptions of competence and well-being among youth exposed to disasters. Appl Dev Sci. 2018;22:29–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2016.1219229.

Weems CF, Graham RA. Resilience and trajectories of posttraumatic stress among youth exposed to disaster. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24:2–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2013.0042.

Jaycox LH, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Walker DW, Langley AK, Gegenheimer KL, et al. Children’s mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: a field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:223–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20518.

UN-General Assembly. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. In: Proceedings of the Third United Nations World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction, Sendai, Japan, 14–18 March 2015.

Jaycox LH, Langley AK, Stein BD, Wong M, Sharma P, Scott M, et al. Support for students exposed to trauma: a pilot study. Sch Ment Heal. 2009;1:49–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-009-9007-8.

Langley AK, Gonzalez A, Sugar CA, Solis D, Jaycox L. Bounce back: effectiveness of an elementary school-based intervention for multicultural children exposed to traumatic events. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83:853–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000051.

Powell T, Holleran-Steiker L. Supporting children after a disaster: a case study of a psychosocial school-based intervention. Clin Soc Work J. 2017;45:176–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0557-y.

Dods J. Bringing trauma to school: sharing the educational experience of three youths. Exceptionality Education International. 2015;25:111–35.

•• Bruns EJ, Duong MT, Lyon AR, Pullmann MD, Cook CR, Cheney D, et al. Fostering SMART partnerships to develop an effective continuum of behavioral health services and supports in schools. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86:156–70. The authors illustrate the value of MTSS through review of how these structures can facilitate access to mental health services, increase the effectiveness of mental health services, and provide empirical support for school-based mental health interventions at each tier. The authors also operationalize this work though description of an effective community-academic partnership and present a set of recommendations relative to research and practice improvement efforts for addressing mental, emotional, and behavioral problems through effective school mental health programming.

Shemesh E, Newcorn JH, Rockmore L, Shneider BL, Emre S, Gelb BD, et al. Comparison of parent and child reports of emotional trauma symptoms in pediatric outpatient settings. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e582–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2201.

Stover CS, Hahn H, Im JYJ, Berkowitz S. Agreement of parent and child reports of trauma exposure and symptoms in the early aftermath of a traumatic event. Psychol Trauma. 2010;2:159–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019156.

Langley AK, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Jaycox LH, Schonlau M, Scott M, et al. Trauma exposure and mental health problems among school children 15 months post-Hurricane Katrina. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2013;6:143–56.

• Vona P, Meyer A, Hoover S, Cicchetti C. A tool for creating safe supportive and trauma responsive schools; 2017: retrieved from: http://csmh.umaryland.edu/media/SOM/Microsites/CSMH/docs/Conferences/AnnualConference/22nd-Annual-Conference/Presentations/10-15-RL/CS-5.13-Measure-and-Improve-Your-School's-Trauma-Responsiveness-%E2%80%93-Introducing-a-Free,-Online-Trauma-Responsive-School-Self-Assessment.pdf. This reference provides illustrative examples of trauma-responsive practices and intervention programming within MTSS frameworks as well as implications for assessing program effectiveness.

Distel LML, Torres SA, Ros AM, Brewer SK, Raviv T, Coyne C, et al. Evaluating the implementation of Bounce Back: clinicians’ perspectives on a school-based trauma intervention, Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2019.1565501

Post-Harvey, Houston teachers learn to respond to trauma. Retrieved from: https://kognito.com/articles/post-harvey-houston-teachers-learn-to-respond-to-trauma. Accessed 9 Jul 2019.

Markle RS, Splett JW, Maras MA, Weston KJ. Effective school teams: Benefits, barriers, and best practices. In: Weist MD, Lever NA, Bradshaw CP, Sarno Owens J, editors. Issues in clinical child psychology. Handbook of school mental health: research, training, practice, and policy. New York: Springer Science + Business Media; 2014. p. 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7624-5_5.

Crone DA, Hawken LS, Horner RH. Responding to problem behavior in schools, second edition: the behavior education program. New York: Guilford Press; 2010.

Kourea L, Lo Y-Y, Owens T. Using parental input to blend cultural responsiveness and teaching of classroom expectations for at-risk Black kindergarteners in a SWPBS school. Behav Disord. 2016;41:226–40. https://doi.org/10.17988/bedi-41-04-226-240.1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Child and Family Disaster Psychiatry

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, L.K., Goldberg, M.G. & Tran, MH.D. Promoting Student Success: How Do We Best Support Child and Youth Survivors of Catastrophic Events?. Curr Psychiatry Rep 21, 82 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1067-3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1067-3