Abstract

Purpose of Review

In other disease states, adherence to behavioral therapies has gained attention, with a greater amount of studies discussing, defining, and optimizing adherence. For example, a meta-analysis formally discussed adherence in 25 studies of CBT for 11 different disorders, with only 6 of the 25 omitting addressing or defining adherence. Many studies have discussed the use of text messages, graph-based adherence rates, and email/telephone reminders to improve adherence. This paper examined the available literature regarding adherence to behavioral therapy for migraine as well as adherence to similar therapies in other disease states. The goal of this research is to apply lessons learned from adherence to behavioral therapy for other diseases in better understanding how we can improve adherence to behavioral therapy for migraine.

Recent Findings

Treatment for migraine typically includes both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapies, including progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and biofeedback. Behavioral therapies have been shown to significantly reduce headache frequency and intensity, but high attrition rates and suboptimal adherence can undermine their efficacy. Traditionally, adherence to behavioral therapy has been defined by self-report, including paper headache diaries and assignments. In person attendance has also been employed as a method of defining and monitoring adherence. With the advent of personal electronics, measurements of adherence have shifted to include electronic-based methods such as computer-based programs and mobile-based therapies. Furthermore, some studies have taken advantage of electronic methods such as email reminders, push notifications, and other mobile-based reminders to optimize adherence. The JITA-I, a novel method of engaging individual patient adherence, has also been suggested as a possible method to improve adherence by tailoring engagement with a mobile health app-based on patient input. These novel methods may be utilized in behavioral therapy for migraine for further optimizing adherence.

Summary

Few intervention studies to date have addressed the optimal ways to impact adherence to migraine behavioral therapy. Further research is required regarding adherence with behavioral therapies, specifically via mobile health interventions to better understand how to define and improve adherence via this novel forum. Once we are able to understand optimal methods of tracking adherence, we will be better equipped to understand the role of adherence in shaping outcomes for behavioral therapy in migraine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Level-A evidence for migraine prevention includes both pharmacologic and behavioral therapy (relaxation, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and biofeedback) [1]. The best treatment for migraine prevention typically consists of a combination of both medications and behavioral therapies [2,3,4]. Meta-analyses of these behavioral therapies have consistently shown significant reductions in migraine frequency, ranging from 35 to 50% reduction in headache activity [5]. In addition, behavioral therapies have minimal to no side effects [6] and are cost competitive compared to pharmacologic interventions [7]. However, in order for these treatments to be effective, they need to be adhered to. In general, adherence is defined as “the extent to which a person’s behavior coincides with medical or health advice” [8] and proves to be an ongoing challenge for both pharmacologic [9] and non-pharmacologic therapies for migraine. Adherence has been shown to decline with more frequent and complex pharmacologic regimens, [10] with even lower rates seen in behavioral therapies. The definition of adherence to behavioral therapy for migraine, specifically, varies widely among studies evaluating its use. Many studies opt out of defining or discussing adherence and others define good adherence as completion of at least 60% of CBT-related assignments with “good” or “excellent” quality as evaluated by the counselor [3]. While behavioral therapies have consistently been shown to improve outcomes of migraine patients, their efficacy may be limited by adherence and high attrition rates.

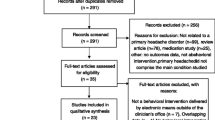

Interestingly, the majority of studies evaluating behavioral therapies in migraine do not include discussions of adherence and potential methods of improving the extent to which patients comply with treatment. In a systematic review of 23 studies on adherence and outcomes for electronically based migraine behavioral treatment, only two studies included absolute rates of adherence and they mention that the rates were suboptimal [11]. A retrospective review estimated adherence rates of 52 to 86% with behavioral treatment [12••]. Engel et al. reported that the average patient adherence to progressive muscle relaxation was 84% [range 36–100%] in pediatric patients with migraine [13]. Other studies evaluating behavioral treatment in the pediatric population estimated adherence rates of 44% [14] and 52% [15]. In addition, a recent study in the adult population showed only about half of participants who were referred to behavioral therapy by a headache specialist even initiated calling a therapist for behavioral treatment of migraine [16••]. Many studies evaluating the use of behavioral therapies for migraine, in addition, do not address methods of improving adherence.

We sought to (1) examine the literature regarding adherence to migraine behavioral therapy to date, (2) briefly review the behavioral adherence literature from other disease states, and (3) consider how these methods might be implemented in migraine behavioral therapy.

Behavioral Therapy Adherence in Headache Research

Traditional Tracking of Behavioral Therapy Adherence in Headache Research

In the past, adherence to behavioral therapy for migraine has been evaluated using self-report [17, 18] and attendance at in-person sessions or a combination thereof. Paper headache diary assignments were used to record self-reported adherence to daily lifestyle recommendations [19]. Examples of how adherence was assessed are as follows: In a randomized controlled trial evaluating beta blocker, brief behavioral migraine management, or a combination of both in 232 adults with migraine, adherence to the interventions was defined as completion of homework assignments and four in-person visits where subjects learned migraine behavioral management skills. Adherence in this particular study was maximized with instructional handouts and three monthly phone contacts. In a pediatric study evaluating CBT and amitriptyline versus headache education with amitriptyline alone, adherence was evaluated with (1) a daily headache diary and (2) attendance at an in-person CBT session [20••].

Some researchers have developed methods to try to optimize adherence to migraine-based behavioral therapies by using more visual and educational modalities. Visual reminders such as charts for self-monitoring are commonly employed in the adolescent population [21]. Educational strategies including teaching the importance of adherence in order to maximize therapeutic potential are another tactic to improve adherence [22]. However, many of these studies have continued to include use self-report for adherence checks.

Tracking Behavioral Therapy Adherence Using Electronic Interventions

Electronic health interventions have been shown to be feasible and possibly improve the access of populations who may not have access to more traditional forms of health care [23]. Initial electronic headache behavioral studies used CD roms, Internet delivered via the computer, and mobile web-based headache behavioral therapies. Sorbi et al. demonstrated the feasibility of a mobile web-based Online Digital Assistance (ODA) program combining a mobile electronic diary and self-relaxation for patients with chronic migraine, with only 6.8% of potential diary entries lost due to program glitches [24]. Three additional studies showed that Internet-based programs can successfully be employed in the behavioral treatment of headache [25,26,27] although high drop-out rates were of concern in all three studies. Most of these studies have focused on the electronic diary as an intervention, and have not fully assessed adherence to the dose and duration of the behavioral therapy itself.

Some studies have utilized electronic methods such as emails and electronically based reminders to improve adherence [28, 29]. For example, in one study using an Internet-based tool for migraine, the study used automatic reminder emails to remind subjects to complete paper diaries [30]. Furthermore, some behavioral therapy programs have been developed such that participants need to complete electronic diary entries in order to enter the next day’s data. In the same study, the electronic diary necessitated that subjects fill out daily information in order to move to the next day, thereby mandating adherence with daily data. Another study evaluated patient acceptance of MyMigraine, an Internet-based behavioral training aid that showed good user acceptance and no patient drop-outs [31].

In 2018, it is estimated that approximately half of the world’s population utilizing smartphones will have downloaded a mobile health app [32]. Thus, to keep up in headache medicine, electronic headache diaries are increasingly common, with over 100 commercial headache apps currently available [11]. The ongoing Women’s Health and Migraine (WHAM) trial evaluates the efficacy of behavioral weight loss intervention in improving migraine symptoms and frequency utilizing smartphone-based headache diaries. Electronic adherence will be assessed on a daily basis remotely, and noncompliant patients will be contacted by study personnel [33]. One app that was recently developed, RELAXaHEAD, has progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) and an electronic headache diary and may be used to assess the dose and frequency of the behavioral therapy [34]. Overall, electronic apps have enabled investigators to potentially better assess adherence to daily assignments completed as part of the behavioral treatment program for headache [35]. However, there is scant evidence on tracking adherence to behavioral therapy in headache using headache apps.

Behavioral Adherence in Other Disease States

As in headache treatment, adherence to behavioral therapies in other disease states has consistently been shown to improve results. For example, in a large study of 3876 patients undergoing Internet-based CBT for depression, adherence with CBT was significantly associated with less depressive symptoms and greater treatment response [36]. Importantly, adherence to behavioral therapies has gained more attention in other disease states, with more studies defining adherence, discussing adherence, and suggesting electronic tools for improving adherence. A retrospective review of 69 studies of electronic therapies across disease states defined adherence as the number of logins and the mean number of completed modules [37]. Other meta-analyses do not formally define adherence but discuss rates of adherence as well as potential tools to improve adherence. For example, a meta-analysis of psychotherapy and other behavioral treatments via mobile technology reviewed 25 clinical trials testing smartphone apps, text messaging, or personal device assistants (PDAs) as treatment supplements [38•]. The meta-analysis did not evaluate individual trial adherence rates but did mention the use of apps to estimate in-between session treatment adherence and practice of skills. A second meta-analysis formally discussed adherence in 25 studies of Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in children and adolescents for 11 different disorders [39]. Of the 25 studies, 5 studies reported the percentage of participants completing all modules while 6 studies did not officially address or define treatment adherence.

Internet-based interventions have been discussed in other fields as potential targets for improving adherence, thereby improving results. For example, a study of Internet-based social phobia behavioral interventions showed that Internet-delivered prompts can improve the efficacy of the intervention [40] Text messages have been effective reminders to optimize adherence in weight loss, [41] diabetes management, [42], and smoking cessation [43]. A meta-analysis of Internet-based CBT for insomnia included two studies that used text messages to reinforce weekly adherence logs to treatment [44]. In addition, a study of CBT for insomnia employed a novel web-based CBT program versus placebo and utilized time stamps of page views and entries as methods of adherence tracking [45]. Other app-based novel methods have been employed successfully in the effort to improve adherence in other fields. In one study, push notifications were sent via the Internet to individual patient apps as a reminder to complete data [46]. Additionally, mobile apps have been used in CBT administration for depression to provide graph-based adherence rates to CBT homework in motivating users between sessions [47] as well as text message reminders for noncompliant users. A recent review of smartphone apps employed for mental health suggested that web-based treatments that have built-in email or telephone reminders easily increase adherence and may even reduce patient dropout [48].

More recently, the just-in-time intervention (JITAI) has been identified in other fields as a possible method of further engaging patient adherence and optimizing benefit from smartphone-based behavioral interventions [49••]. JITAI’s are designed to monitor the dynamics of the patient using the app and offer individualized real-time health interventions. For example, the ACHESS trial uses a JITAI for alcoholics desiring supportive services. It utilizes GPS technology to identify patients approaching high-risk locations such as bars. If the individual does approach a high-risk location, the app will alert the patient [50]. Another JITAI, FOCUS, was designed for patients with schizophrenia and prompts them three times a day to assess certain illness-related domains [51]. If the patients engage with the prompt, the app leads them to assessments identifying difficulty within these domains and offering self-management strategies only if difficulties are in fact identified. This approach may prove to be beneficial for patients with schizophrenia given prior research showing that changes in mood are more likely to occur with too-frequent prompts for self-report. The JITAI is a novel method of individualizing patient engagement with a health-based app and may improve adherence. The use of tailored prompts based on patient engagement may benefit behavioral therapy in the migraine domain as well.

Future Directions/Conclusion

The use of electronic interventions and apps may offer an engaging alternative to traditional methods of delivering behavioral therapy. Firstly, the audiovisual functionalities of the app may improve patient engagement [52]. In addition, the ability of some apps to synch with calendar appointments may improve patient knowledge of appointments and thereby improve adherence [53]. App-based behavioral therapies allow for tracking adherence; researchers can obtain real-time information about how often the app is used and whether the patient is practicing the behavioral therapy technique. The design of the app can also be changed to improve adherence, including tailoring reminders and prompting users to interact with the app at various time points [53].

As with behavioral therapy for other diseases, the challenge with migraine behavioral therapy remains how to optimize adherence because poor adherence with behavioral therapy undermines treatment efficacy. It has been shown that electronic strategies of improving adherence have been successfully used in other fields. For example, text message reminders, Internet-based prompts, and time stamps of entries have all been used in order to improve adherence. Other self-motivational strategies such as in-built graphs of adherence rates have been employed and may benefit patients who respond to ongoing visual feedback. Push notifications are yet another method of improving adherence that have been used in other fields and may prove to help in the migraine field as well. Typically, the user will opt-in to receive alerts and will receive notifications even when the app is not open on the person’s smartphone [54]. In this sense, push notifications can easily prompt users throughout the day to engage with the therapy. It is clear that Internet-based reminders, whether in the push notification, text, or email-based format, will increase adherence and possibly decrease patient dropout for behavioral therapies.

Few intervention studies to date have addressed the optimal ways to impact adherence to migraine behavioral therapy. The field of headache behavioral therapy may benefit from a JITAI already implemented in other disease states. For example, a JITAI could use technology already implemented to decrease sedentary behavior in office workers by sending prompts only after 30 min of uninterrupted computer time in order to increase engagement with behavioral therapy for migraine [54]. The JITAI could track engagement with the behavioral therapy via an app and send individualized prompts only if patients stop the behavioral therapy earlier than the allotted treatment time. It stands to reason that adherence with behavioral therapy for migraine could potentially improve with a tailored approach similar to that already used for other diseases. In general, further research is required regarding adherence with behavioral therapies, specifically via mobile health interventions to better understand how to define and improve adherence via this novel forum. Moreover, once we are able to create a consensus definition for adherence as well as understand optimal methods of tracking adherence, we will be better equipped to understand the role of adherence in shaping outcomes for behavioral therapy in migraine.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Campbell J, Penzien D, Wall E. Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache: behavioral and physical treatments. 2000.

Matchar DB, Harpole L, Samsa GP, et al. The headache management trial: a randomized study of coordinated care. Headache. 2008;48(9):1294–310.

Holroyd KA, Cottrell CK, O’Donnell FJ, et al. Effect of preventive (beta blocker) treatment, behavioural migraine management, or their combination on outcomes of optimised acute treatment in frequent migraine: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c4871. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4871.

Powers SW, Kashikar-Zuck SM, Allen JR, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy plus amitriptyline for chronic migraine in children and adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(24):2622–30. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.282533.

Penzien DB, Rains JC, Andrasik F. Behavioral management of recurrent headache: three decades of experience and empiricism. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2002;27(2):163–81.

Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55(6):754–62.

Schafer AM, Rains JC, Penzien DB, Groban L, Smitherman TA, Houle TT. Direct costs of preventive headache treatments: comparison of behavioral and pharmacologic approaches. Headache. 2011;51(6):1526.

Horwitz R. Adherence to treatment and health outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(16):1863.

Seng EK, Rains JA, Nicholson RA, Lipton RB. Improving medication adherence in migraine treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2015;19(6):24–015–0498-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-015-0498-8.

Claxton A, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1296.

Minen MT, Torous J, Raynowska J, et al. Electronic behavioral interventions for headache: A systematic review. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:51–016-0608-y. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0608-y.

•• Ramsey RR, Ryan JL, Hershey AD, Powers SW, Aylward BS, Hommel KA. Treatment adherence in patients with headache: A systematic review. Headache. 2014;54(5):795–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12353. This was a study of adherence for children undergoing progressive muscle relaxation for migraine. Adherence in this study was defined by the number of correct “relaxation passwords of the day” as recorded on the individual child’s relaxation log. The study also found a significant relationship between adherence and number of headache free days.

Engel JM. Children’s compliance with progressive relaxation procedures for improving headache control. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 1993;13:219.

Wisniewski JJ, Genshaft JL, Mulick JA, Coury DL, Hammer D. Relaxation therapy and compliance in the treatment of adolescent headache. Headache. 1988;28:612.

Guibert MB, Firestone P, McGrath P, Goodman JT, Cunningham JS. Compliance factors in the behavioural treatment of headache in children and adolescents. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement. 1990;22(1):37.

•• Minen MT, Azarchi S, Sobolev R, Shallcross A, Hapern A, Berk T, et al. Factors related to migraine patients' decisions to initiate behavioral migraine treatment following a headache specialist’s recommendations: a prospective observational study. In: Pain medicine; June 2018. This was a multi center randomized controlled trial for adults with symptoms of depression (with scores of ≥ 10 on a standardized questionnaire for depression) who were randomised to receive a commercially produced computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) program or a free to use cCBT program in addition to standard of care. Participants adhered to self report of symptoms. The study found that a commercially available cCBT or free to use CBT was not superior to general practitioner standard of care.

Gilbody S, Littlewood E, Hewitt C, Brierley G, Tharmanathan P, Araya R, et al. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy (cCBT) as treatment for depression in primary care (REEACT trial): large scale pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;351:5627.

Tassorelli C, Sances G, Allena M, Ghiotto N, Bendtsen L, Olesen J, et al. The usefulness and applicability of a basic headache diary before first consultation: results of a pilot study conducted in two centres. Cephalagia. 2008;28(10):1023.

Lipchik GL, Holroyd KA, Nash JM. Cognitive-behavioral management of recurrent headache disorders: a minimal-therapist-contact approach. In: Psychological approaches to pain management. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Pubs; 2002. p. 356.

•• Kroon Van Diest AM, Ramsey R, Kashikar-Zuck S, et al. Treatment adherence in child and adolescent chronic migraine patients: results from the cognitive behavioral therapy and amitriptyline trial. Clin J Pain. 2017;33:892. This paper reviewed the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of migraine in children and adolescents. As part of the management section, the paper discusses relaxation techniques that are commonly employed in the armamentarium against pediatric and adolescent headache. The paper also discusses strategies commonly employed in the effort to improve patient adherence to relaxation techniques. Visual reminders to cue compliance, such as charts for self monitoring, are suggested as a possible tool.

Kabbouche MAGD. Management of migraine in adolescents. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(3):535.

Faedda N, Cerutti R, Verdecchia P, Migliorini D, Arruda M, Guidetti V. Behavioral management of headache in children and adolescents. J Headache Pain. 2016;17(1):80.

Ahern DK, Kreslake JM, Phalen JM. What is eHealth (6): perspectives on the evolution of eHealth research. J Med Internet Res. 2006;8(1):e4.

Sorbi M, Mak S, Houtveen J, Kleiboer A, van Doornen L. Mobile web-based monitoring and coaching: feasibility in chronic migraine. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(5):e38.

Andersson G, Lundström P, Ström L. Internet-based treatment of headache: does telephone contact add anything? Headache. 2003;43:353.

Devineni TBE. A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based treatment for chronic headache. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:277.

Ström L, Pettersson R, Andersson G. A controlled trial of self-help treatment of recurrent headache conducted via the internet. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:722.

Bromberg J, Wood ME, Black RA, Surette DA, Zacharoff KL, Chiauzzi EJ. A randomized trial of a web-based intervention to improve migraine self-management and coping. Headache. 2012;52(2):244–61.

Dear BF, Titov N, Perry KN, Johnston L, Wootton BM, Terides MD, et al. The pain course: a randomised controlled trial of a clinician-guided internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy program for managing chronic pain and emotional well-being. Pain. 2013;154(6):942.

Hedborg K, Muhr C. Multimodal behavioral treatment of migraine: an internet-administered, randomized, controlled trial. Ups J Med Sci. 2011;116:169–86.

Sorbi MJ, van der Vaart R. User acceptance of an internet training aid for migraine self-management. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16(1):30.

Jahns RG. Jahns R-G. 500m people will be us- ing healthcare mobile applications in 2015 . Updated 2010. Accessed 06/12, 2018.

Bond DS, O’Leary KC, Thomas JG, et al. Can weight loss improve migraine headaches in obese women? Rationale and design of the WHAM randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(1):133.

Minen MT, Jalloh A, Ortega E, Powers SW, Sevick MA, Lipton RB. User design and experience preferences in a novel smartphone application for migraine management: a think aloud study of the RELAXaHEAD application. Pain Med. 2018.

Ramsey R, Holbein C, Powers S, Hershey A, Kabbouche MA, et al. A pilot investigation of a mobile phone application and progressive reminder system to improve adherence to daily prevention treatment in adolescents and young adults with migraine. Cephalalgia. 2018.

Stawarz K, Preist C, Tallon D, Wiles N, Coyle D. User experience of cognitive behavioral therapy apps for depression: An analysis of app functionality and user reviews. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(6).

Donkin L, Christensen H, Naismith SL, Neal B, Hickie IB, Glozier N. A systematic review of the impact of adherence on the effectiveness of e-therapies. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e52.

• Lindhiem O, Bennett CB, Rosen D, Silk J. Mobile technology boosts the effectiveness of psychotherapy and behavioral interventions: a meta-analysis. Behav Modif. 2015;39(6):785. This was a comprehensive systemic review and meta-analysis of internet delivered CBT (iCBT) for children and adolescents. The review included twenty five studies of iCBT for 11 different disorders. Treatment adherence and therapist time varied largely amongst sutudies. Twenty-four studies (N = 1882) were eventually included in the. There was a moderate between-group effect size of the iCBT group when compared with the waitlist, g = 0.62, 95% CI [0.41, 0.84], suggesting that iCBT for multiple different disorders can be successfully used.

Vigerland S, Lenhard F, Bonnert M, Lalouni M, Hedman E, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;50:1.

Tulbure BT, Szentagotai A, David O, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder in Romania: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0123997.

Patrick K, Raab F, Adams MA, Dillon L, Zabinski M, Rock CL, et al. Text message-based intervention for weight loss: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(1):e1.

Kim HS, Yoo YS, Shim HS. Effects of an internet-based intervention on plasma glucose levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Nurs Care Qual. 2005;20(4):335.

Rodgers A, Corbett T, Bramley D, Riddell T, Wills M, Lin R, et al. Do u smoke after txt? Results of a randomised trial of smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging. Tob Control. 2005;14(4):255.

Ye Y, Chen N, Chen J, et al. Internet-based cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i): a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):E010707.

Espie CA, Kyle SD, Williams C, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep. 2012;35(6):769.

Push notification. https://searchmobilecomputing.techtarget.com/definition/push-notification. Updated 2016. Accessed 06/01, 2018.

Bakker D, Kazantzis N, Rickwood D, Rickard N. Mental health smartphone apps: review and evidence-based recommendations for future developments. JMIR Mental Health. 2016;3(1):e7.

Jones K, Lekhak N, Kaewluang N. Using mobile phones and short message service to deliver self-management interventions for chronic conditions: a meta-review. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2014;11(2):81.

•• Nahum-Shani I, Smith SN, Spring BJ, Collins LM, Witkiewitz K, Tewari A, et al. Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Ann Behavioral Med. 2018;52(6):446. This was a randomized clinical trial involving 5 residential programs for patients meeting the criteria for DSM-IV alcohol dependence (n = 349). Patients were randomized to usual treatment (n = 179) or usual treatment plus a smartphone (n = 170) with the Addiction-Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (A-CHESS) application, designed to improve care for alcohol dependence. Patients in the A-CHESS group had significantly fewer risky drinking days than did the control patients (mean difference, 1.37; 95% CI, 0.46-2.27; P = .003).

Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih M-Y, et al. A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry. 2014;71(5):566.

Ben-Zeev D, Brenner CJ, Begale M, Duffecy J, Mohr DC, Mueser KT. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a smartphone intervention for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(6):1244.

Dayer L, Heldenbrand S, Anderson P, Gubbins PO, Martin BC. Smartphone medication adherence apps: potential benefits to patients and providers. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013;53(2):172.

Boulos MNK, Brewer AC, Karimkhani C, Buller DB, Dellavalle RP. Mobile medical and health apps: State of the art, concerns, regulatory control and certification. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics. 2014;5(3229).

Dantzig S, Geleijnse G, Halteren AT. Toward a persuasive mobile application to reduce sedentary behavior. Pers Ubiquit Comput. 2013;17(6):1237–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Mia Minen has funding from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) K23 AT009706-01 and the American Academy of Neurology (AAN)-American Brain Foundation (ABF) Practice Research Training Fellowship. Alexandra Gewirtz declares no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Topical Collection on Psychological and Behavioral Aspects of Headache and Pain

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gewirtz, A., Minen, M. Adherence to Behavioral Therapy for Migraine: Knowledge to Date, Mechanisms for Assessing Adherence, and Methods for Improving Adherence. Curr Pain Headache Rep 23, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-019-0739-3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-019-0739-3