Abstract

Purpose of Review

The benefits of arts in improving well-being in end-of-life patients have been stated by the WHO. To inspire clinical practice and future research, we performed a mapping review of the current evidence on the effectiveness of art therapy interventions in stage III and IV cancer patients and their relatives.

Recent Findings

We identified 14 studies. Benefits reported by the authors were grouped as improved emotional and spiritual condition, symptom relief, perception of well-being, satisfaction, and helpfulness. As a body of evidence, notable limitations were observed: Only 1 study was a randomized controlled trial (RCT), and there was heterogeneity in the interventions and outcome measures.

Summary

This mapping review highlights the evidence available on the effectiveness of art therapy in advanced cancer, which remains limited and presents specific challenges. It also provides a visual representation of the reported benefits, encouraging further and more rigorous investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Advanced cancer represents a huge threat to the affected person as a whole. Often, patients face intense fear, prolonged stress, and much suffering as a consequence of the progression of the disease, experiencing pain or other symptoms in a multiplied and intensified way, accumulating many functional losses, and feeling the close possibility of death. Their relatives also suffer from these circumstances. As the WHO has stated [1], the appropriate response to this situation is the application of comprehensive palliative care. Unfortunately, palliative care is far from being an available and equitable resource in all health systems and countries.

Among the various types of complementary interventions that are suggested as part of the palliative approach to address patients’ physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs are those based on health-applied arts. The visual, musical, physical, literary, and theatrical arts applicable to health represent a broad field that encompasses very varied disciplines and interventions, usually considered complex due to their holistic nature. Another recent authoritative WHO report [2••] notes the potential benefits of some of these approaches in supporting end-of-life care and bereavement. Also, a recent international handbook offers a cross-cultural perspective of how art therapy can help individuals, groups, families, communities, and nations facing death and dying as well as grief and loss [3••].

The most recognized international sources [4, 5] state that art therapy requires the use of art media for self-expression, reflection, and communication in the presence of a trained art therapist. According to these sources, as an integrative mental health and human services profession, art therapy enriches the lives of users through active art-making, creative process, applied psychological theory, and human experience within a psychotherapeutic relationship. Users do not need to have any previous art experience or knowledge. Within this context, art is not a diagnostic tool, a lesson, or a recreational activity, although the sessions can be enjoyable. Art therapy is provided in groups or individually, with personalized interventions according to the therapeutic needs of the users, and includes patient assessment, treatment, and evaluation of response [6]. For appropriate professional practice as an art therapist, the emphasis has been repeatedly placed on the importance of specific training and deep personal knowledge based on introspection [4,5,6]. However, the multimodal essence of art therapy, which affects different aspects of the individual, represents a considerable challenge regarding the appropriateness of research methodologies to evaluate the many and diverse possible interventions.

Art-making interventions and creative art therapies are largely used in many cancer care settings, particularly in the early stages, in which significant improvements in anxiety, depression, pain intensity, and quality of life have been reported by several systematic reviews [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], four with meta-analysis [8, 9, 12, 14]. But evidence about the use of art therapy for palliative purposes in advanced cancer patients is not easily available due to the difficulties in conducting research studies in these complex clinical situations. We, therefore, sought to contribute to this field by conducting a mapping review focused on identifying and describing the clinical studies that have assessed the effectiveness of art therapy in patients with advanced cancer and their families.

Methods

Study Eligibility Criteria

Type of Study

We included systematic reviews and quantitative or qualitative primary studies. We excluded narrative reviews, case series, case reports, research protocols, editorials, letters, conference proceedings, dissertation abstracts, book reviews, and book chapters.

Type of Participants

We included advanced cancer patients and their relatives/caregivers. Advanced cancer was defined as that classified in the studies as stages III or IV. Studies that included at least 50% of patients in these stages were selected.

Type of Interventions

We included interventions with an active visual art-making and creative process involving the participants in the presence of a trained art therapist. All types of control modalities were accepted. We excluded other creative therapy interventions such as music therapy, dance/movement therapy, drama therapy, psychodrama, and poetry therapy.

Language

We included full texts in English, French, or Spanish.

Search Methods for Identification of Studies

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed), CINAHL, and PsycINFO (both via EBSCOHost) from January 2000 to January 2022. We defined a list of controlled vocabulary and text terms related to the intervention and the population of interest. The searches were adapted to the requirements of each database. We did not set restrictions for the electronic searches. Additionally, we checked the reference lists from relevant documents to retrieve additional studies.

Data Collection and Analysis

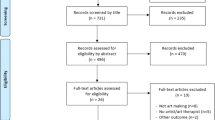

We performed a title and abstract screening of the results obtained from the search conducted by one author (IS). We then obtained the full text of the selected studies, and they were assessed by two authors (NC and AP), independently and in duplicate. The studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were recorded with their reasons for exclusion. Any disagreements, either in the title-and-abstract or the full-text phase, were solved by consensus or, when necessary, by the remaining authors (XB and IS). The selection process was detailed as a PRISMA flow chart.

The following data were extracted from each study and tabulated: authors, year of publication, country, number and age of participants, clinical setting, proportion of stage III and IV participants in the sample, description of the intervention, outcome measures, and results.

The authors’ conclusions from the quantitative studies were classified for descriptive purposes as “beneficial” or “no differential effect” between the intervention and the comparator. We developed a specific evidence map in which the rows listed the outcomes measured, and the columns contained whether the intervention was reported as “beneficial” or “no differential effect.” Geometrical shapes indicated the study design, while their sizes and colors indicated the number of studies included and the target population of the intervention. Data synthesis was presented as the results of the review, followed by a discussion around the most relevant headings and subheadings that emerged from the results.

Results

The PRISMA flow chart with the selection process of the studies included is detailed in Fig. 1. Table 1 summarizes the study characteristics according to the information reported by the respective authors.

Target Populations and Study Designs

Fourteen studies [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] met the inclusion criteria, among which 9 presented results exclusively in patients, 3 in patients and relatives, 1 exclusively in relatives, and 1 in relatives and health care professionals. The study designs were 1 RCT (in patients), 9 quasi-experimental studies (among which were 1 non-randomized controlled study, 3 pre-post studies, and 5 pre-post studies combined with observational studies), and qualitative designs (3 in patients and 1 in relatives/professionals). Depending on the corresponding study design, control groups consisted of participants that served as their own comparators (9 studies), or taking standard care (3 studies) as a comparator.

Samples and Patient Characteristics

The total sample consisted of 540 patients (sample range: 10–177, sample median of quantitative studies: 35), of which 325 were women and 215 were men, with a mean age of 57.6 years (range: 19–85 years); there were 131 family members. The proportion of stage III and IV patients in the total sample was 80.5% (9 of the 14 studies had 100%). The sample populations were inpatients in 8 of the 14 studies, outpatients in 5 studies, and mixed in 1 study. Settings were in palliative care/hospice units in 7 of the 14 studies, in oncology/hematology services in 6 studies, and mixed in 1 study.

Art Therapy Interventions

Interventions were carried out as an individual in 11 studies and as a group in 3 studies, with a mean duration of 53 min (20–97 min) and 150 min, respectively. All interventions fulfilled the art therapy conditions of fostering the generation of artwork using visual art materials followed by free verbal expression and meaning-making favored by the art therapist. Painting (including collage), drawing, and claying were the most used artistic methods. However, others were sometimes introduced, such as photographing, contemplating reproductions of artworks, listening to music, and reading poems. Occasionally, craft making, guided visualizations, walks in a natural environment, meditation, or mindful breathing exercises were combined with the artistic activities. Consequently, the scheme and sequence of the interventions were variable. In 6 of the 14 studies, reference was made to the specific training of the art therapist, with terms such as qualified, certified, or accredited, in the text or in the authors’ credentials.

Outcome Evaluation

In patients, authors used validated instruments to measure outcomes that included symptoms (pain, tiredness, ill-being, insomnia), emotional aspects (anxiety, depression, distress), spiritual well-being, sense of coherence, and quality of life. In relatives, they included anxiety, depression, somatization, and bereavement.

Other outcomes were evaluated using instruments (scales, questionnaires) that had not previously undergone a validation process. This was the case in patients for the assessment of aesthetic aspects (perception and appreciation of beauty, degree of pleasure from the artworks, creativity), perceived helpfulness from the intervention, meaning of life, sadness, social unavailability, and lack of wishes. This was also the case in relatives for perceived helpfulness, satisfaction, and support service evaluation.

Art Therapy Effects

Figure 2 shows the map of the effect of the interventions for the 22 outcomes evaluated.

Table 2 describes which art therapy modalities were related to the observed effects. These modalities had in common the artistic techniques of painting or collage. However, no comparison study has been reported to determine which method and sequence of techniques is the most helpful for which symptom or condition.

In patients, anxiety and depression were the outcomes that were evaluated most frequently (8 studies) [18, 20, 23,24,25,26,27,28], mainly using the HADS or ESAS scales. Six studies showed statistically significant reductions, 5 compared to their own controls [18, 20, 23, 26, 27] and 1 compared to a standard care group [25].

In 3 of the 5 studies that assessed the intensity of symptoms using ESAS with patients as their own controls, significant reductions were observed in pain [18, 20, 23], anxiety, and depression. The same proportion of studies showed a significant reduction in ill-being [18, 20, 23]. Two of these studies showed a significant improvement in fatigue [21, 28].

Statistically significant improvements in spiritual well-being in patients, evaluated using the FACIT-Sp scale, were observed in two studies [22, 23], one of them with RCT design [28], comparing a 6-session individual modality art therapy intervention group with a standard care control group in 40 patients. In this latter study, when the sample was not 100% composed of patients with advanced cancer, they performed statistical analysis to examine the effects of the intervention as a function of two variables: cancer stage and participants’ age. The results suggested that the effect of art therapy treatment versus standard treatment was greater in young patients than in older patients, but that there were no differences according to cancer stage. In a third study [24], a significant increase was observed in the score for the search for the meaning of life (using a non-validated scale), the participating patients being their own controls. In addition, one observational study [16] and two qualitative studies [15, 21] reported benefits categorized in the existential and/or spiritual sphere.

Regarding specific feelings of the aesthetic experience, two pre-post studies [18, 20] showed statistically significant increases in the degree of creativity and artistic appreciation (perception of beauty), using specific but non-validated self-assessment tools. These results were corroborated by the results of two observational studies [16, 23], in which participants showed a high sense of satisfaction with the creation after the intervention.

In relatives, in one quasi-experimental study [19], significantly fewer symptoms of prolonged grief were observed than in the standard care control group, using the PG13 scale. With non-validated instruments, a significantly greater perceived support service from the hospital was observed compared to the control [19]. Benefits of perceived helpfulness from art therapy and satisfaction with the intervention were also reported in observational studies [20, 23].

No harmful effects were reported. However, one study [24], in which participating patients were their own controls, with no differential effect on the quality of life measured by the EORTC QLQ, mentioned a reduction in role functioning due to a decrease in activities of daily living, which the authors attributed to disease progression during the two months of intervention.

Discussion

This mapping review sought to identify and describe the clinical studies that have assessed the effectiveness of art therapy (defined as a process of art-making within a bond of psychotherapeutic relationship with an art therapist) in patients with advanced cancer and/or their families. Although some reviews already exist on cancer patients [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], to our knowledge, this is the first attempt specifically focused on advanced cancer stages, in order to clarify the soundness of the existing evidence for the use of art therapy in this situation, following an exhaustive database search and providing a user-friendly visual approach.

In our review, only one study was RCT [28]. Most of the other quantitative studies, 9 of 10, were quasi-experimental with heterogeneous types of interventions, variables, and assessment instruments, and most had 1 arm. As is well known, non-pharmacological interventions present specific challenges and are less frequently evaluated through the more demanding design of RCT, compared to drug treatments [29], especially in end-of-life conditions. The great vulnerability of patients who are facing death adds to the difficulty in evaluating a complex holistic intervention that has a personalized approach [30]. Although basic visual arts materials were systematically used in the included studies, specifically those of painting or collage, there was variability in the art activities described in the interventions. This implies a limitation to the need for standardized methods in evidence-based practice research. At the same time, using a flexible, wide range of art experiences is also a defining characteristic and strength of the creative arts therapies to address specific therapeutic issues for individual patients, provided the tailoring is based on the extensive experience of a qualified professional [6].

Taking these limitations into account, the reported benefits of art therapy in the included studies can be grouped into three categories as presented below.

Improved Emotional and Spiritual Condition

The proximity of death usually causes fear and even terror [31] and can lead to traumatic experiences [32]. The improvement in anxiety and depression [18, 20, 25,26,27] and reduction in the proportion of elevated distress in one RCT [28] were the most mentioned benefits in patients. These results could relate to the calming, relaxing, mindful, and expressive effects of the art therapy sessions described in the observational part of some of these studies and in qualitative designs [16, 17].

Some results suggest the effects of art therapy at a spiritual level. Participants felt more acceptance of their situation, a greater sense of peace and harmony, and strength in spiritual beliefs after the intervention, compared with standard care participants [28]. Own control participants felt improvements in peace, meaning, and faith [27]. Balfour Mount [33] observed that establishing human connections at an intra-, inter-, and transpersonal level can transform experiences of suffering and anguish in the dying into experiences of wholeness and integrity and facilitate a peaceful death. The reported results, together with data from observational [16, 18, 20, 23] and qualitative [15, 21] studies, which mentioned feeling hopeful, happy, and full of gratitude, even in such adverse conditions, suggest that art therapy interventions could address spiritual needs and facilitate the healing connections identified by Mount.

Family caregivers in the context of incurable cancer seem to experience more pronounced anxiety, while patients report greater depressive symptoms [34]. The included studies reported that expressing and communicating feelings after the intervention strengthened relationships with family members during illness, anchored the patient in life [20], and facilitated memory making [17, 21,22,23]. In bereavement, reported benefits included an improvement in psychological symptoms of prolonged grief, perceived good support after art therapy [19], and that the remaining artworks allowed relatives to remember and feel themself linked with their deceased loved ones [19, 20, 22]. These data are in agreement with theoretical postulates about transitional objects [35], the importance of the continuation of the bond in mourning [36], and the reconstruction of meaning [37].

Symptom Relief

The presence of a high level of emotional distress in patients is among the prognostic factors for poor pain control [38]. Among the included studies, three interventions that improved anxiety and depression also reported a significant reduction in pain [18, 20, 23]. Specific factors were related with these effects [18, 20], such as enjoyment while performing the activity, technical satisfaction when creating something, and aesthetic satisfaction once a piece of art is made. Patient’s verbalizations [23] highlighted the physical creative action that allowed a change in their focus of attention from the overwhelming routine of hospitalization and constant concerns about their health and symptoms to a feeling of creativity and freedom with the art. This distraction toward the pleasant art experience has previously been hypothesized as a possible factor for relieving pain [39]. Additionally, a significant reduction in fatigue was reported [18, 20]. This reduction may be related to the relaxing and exciting effects of the sessions described in qualitative studies [15, 17]. Similar effects have previously been reported [40].

Perception of Well-being, Satisfaction, and Helpfulness

In the context of the advanced cancer stage with limited prognosis, reported benefits on patient’s well-being [18, 20, 23] and quality of life [25] are encouraging. Some of the results presented in the previous sections could contribute to these effects. Interventions were perceived as helpful or supportive by patients and relatives [19, 22, 23]. The theory has long described a shift from a passive to an active role through art-making for people who are increasingly losing their autonomy due to illness, and the artworks may be perceived as tangible evidence of their vitality and capacity to control their bodies [41].

A core idea of comprehensive palliative care is that what is transformative for finding peace and authentic well-being in this clinical setting is the conscious connection with death deep in the psyche [42,43,44,45•]. Art therapy, as a mind–body therapeutic approach, has been suggested to contribute to this awareness [43, 46]. Metaphors emerging from the unconscious can be seen as a simplifying process that facilitates the approach of such complex, threatening, and difficult-to-express concepts [47]. Based on our ample experience of art therapy in a palliative care unit, we hypothesize that the intervention, targeting the healthy parts of the person, promotes the emergence of visual metaphors that can function as a filter applied to fears [48, 49].

For integrative oncology and palliative care professionals considering implementing art therapy in their services, we highlight some reflections to optimize this process [50••]. While artistic knowledge and specialization in visual art-making are essential, it is paramount to build a secure bond and therapeutic relationship with the accompanied person or group, facilitate self-reflection on their artworks, and promote meaning-making from the creative process. These competencies are acquired or improved during the training as an art therapist [4, 5]. It encompasses managing specific counseling strategies as well as resorting to personal qualities and presence acquired through introspection. This includes, in the end-of-life setting, the fearless exploration of one’s own mortality and not being afraid of death in the clinical context for an in-depth immersion [43]. It has been asserted that if these competencies are not met, art-making interventions at the end of life “may be little more than a sham; ego-reinforcement techniques masquerading as complementary or integrative therapies” [43].

We identify three limitations. First, an assessment of the methodological quality of the included studies was not performed, mainly due to the nature and heterogeneity of their designs. Our review organizes the evidence reported by the authors, describing results as beneficial even if they could be based on low-quality evidence and subject to bias. Second, in some studies (5 of 14), not all patients had advanced cancer (minimum 50% of the sample), although we consider that they could still provide relevant information. In one of them, the authors performed a statistical analysis that showed that their results were not dependent on the variable cancer stage. It could be hypothesized that in some advanced cancer situations, art therapy interventions may have similar beneficial effects as in earlier stages. Third, despite their prevalence in the addressed topic and their high human value, publications of clinical cases were excluded, due to the difficulty of systematically recording their results and because they constituted only anecdotal evidence.

The research gaps we identified are mainly methodological, due to the lack of RCT designs, the limitations in control conditions, and the heterogeneity in interventions and outcome measures. There is also a population-based gap, due to the absence of studies on child patients and the scarcity of studies on relatives. Art therapy shares some similar challenges with other non-pharmacological interventions [51]. In order to gain credibility and become more widely accepted among practitioners and academics, art therapy effects should be assessed in well-designed and powered RCTs. Solutions to the absence of standardized protocols of interventions and validated placebo/sham can be found with the use of the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) guide (and extensions) [52, 53]. This recognizes the relevance of tailoring and proposes strategies for the improvement of control conditions and description of the most systematic and reproducible components of the intervention, which in art therapy would include the sequence, the techniques, and the materials mostly used. In all study designs, outcome measures should be evaluated using validated assessment scales. In addition, careful mixed-method studies that offer more comprehensive evidence are recommended [54], to expand our understanding of the multiple and complex mechanisms involved in the effectiveness of art therapy interventions. Likewise, the specific professional qualification of the art therapist should be communicated, including the conceptual models on which the intervention is based. Therefore, well-reported, informative studies are needed, with study designs that contribute to a higher level in the current paradigmatic hierarchy of evidence.

Conclusions

The 14 studies included in this mapping review reflect the evidence on the effectiveness of art therapy in advanced cancer, which currently remains low, mostly due to notable methodological limitations and a highly challenging research field. In patients, the main reported benefits were in anxiety, depression, spiritual well-being, symptom relief, and perceived enjoyment and helpfulness. In relatives, benefits in bereavement symptoms and in terms of perceived good support were described. Heterogeneity in outcome measures and a scarcity of RCT designs are methodological gaps to be addressed in further investigation.

Change history

21 September 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-022-01325-w

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

WHO Expert Committee on Cancer Pain Relief and Active Supportive Care & World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care : report of a WHO expert committee [meeting held in Geneva from 3 to 10 July 1989]. World Health Organization; 1990. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39524.

•• Fancourt D, Finn S. What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019 (Health Evidence Network (HEN) synthesis report 67). From an authoritative source in health, this review acknowledges the global evidence (results from over 3000 studies in diverse disciplines) on the contribution of the arts to the prevention, management, and treatment of illness across the lifespan.

•• Wood MJ, Jacobson B, Cridford H. The international handbook of art therapy in palliative and bereavement care. New York and London: Routledge; 2019. This handbook presents multicultural and international perspectives on how art therapy can help to alleviate the distress and suffering of individuals, groups, families, communities, and nations facing death and dying as well as grief and loss.

AATA. About art therapy. The American Art Therapy Association website: https://www.arttherapy.org/upload/2017_DefinitionofProfession.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2021.

BAAT. About art therapy. The British Association of Art Therapists website: https://www.baat.org/About-Art-Therapy. Accessed May 16, 2021.

BradtJ GS. Creative arts therapies defined. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:969–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6145.

Wood MJM, Molassiotis A, Payne S. What research evidence is there for the use of art therapy in the management of symptoms in adults with cancer. A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2011;20(2):135–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1722.

Puetz TW, Morley CA, Herring MP. Effects of creative arts therapies on psycological symptoms and quality of life in patients with cancer. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):960–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.836.

Boehm K, Cramer H, Staroszynski T, Ostermann T. Arts therapies for anxiety, depression and quality of life in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015;20(2):87–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587214555714.

Archer S, Buxton S, Sheffield D. The effect of creative psychological interventions on psychological outcomes for adult cancer patients: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Psychooncology. 2015;24(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3607.

Kim KS, Loring S, Kwekkeboom K. Use of art-making intervention for pain and quality of life among cancer patients. J Holist Nurs. 2018;36(4):341–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010117726633.

Tang Y, Fu F, Gao H, Shen L, Chi I, Bai Z. Art therapy for anxiety, depression, and fatigue in females with breast cancer: a systematic review. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(1):79–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1506855.

Fu W, Huang Y, Lin X, Ren J, Zhang M. The effect of art therapy in women with gynecological cancer: a systematic review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2020;2020, Article ID8063172. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8063172.

Cheng P, Xu L, Zhang J, Liu W, Zhu J. Role of arts therapy in patients with breast and gynecological cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(3):443–52. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0468.

Kennett CE. Participation in a creative arts project can foster hope in a hospice day centre. Palliat Med. 2000;14:419–25. https://doi.org/10.1191/026921600701536255.

Lin MH, Sl M, Kuo YC, Py Wu, Lin CL, Tsai MH, Chen TJ, Hwang SJ. Art therapy for terminal cancer patients in a hospice palliative care unit in Taiwan. Palliat Support Care. 2012;10:51–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951511000587.

Rhondali W, Chirac A, Filbet M. L’art-thérapie en soins palliatifs: une étude qualitative. Médecine palliative. 2013;12:279–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medpal.2012.11.002.

Lefèvre C, Ledoux M, Filbet M. Art therapy among palliative cancer patients: aesthetic dimensions and impacts on symptoms. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(4):376–80. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515001017.

Schaefer MR, Spencer SK, Barnett M, Reynolds NC, Madan-Swain A. Legacy artwork in pediatric oncology: the impact on bereaved caregivers’ psychological functioning and grief. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(9):1124–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0329.

Lefèvre C, Economos G, Tricou C, Perceau-Chambard E, Filbet M. Art therapy and social function in palliative care patients: a mixed-method pilot study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2022;12(e1):e75–82. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001974.

Park S, Song H. The art therapy experiences of patients and their family members in Hospice Palliative Care. Korean J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;23(4):183–97. https://doi.org/10.14475/kjhpc.2020.23.4.183.

Schaefer MR, Wagoner ST, Young ME, Madan-Swain A, Barnett M, Gray WN. Healing the hearts of bereaved parents: impact of legacy artwork on grief in pediatric oncology. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(4):790–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.018.

Collette N, Güell E, Fariñas O, Pascual A. Art therapy in a palliative care unit: symptom relief and perceived helpfulness in patients and their relatives. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(1):103–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.07.027.

Visser A, Op’T Hoog M. Education of creative art therapy to cancer patients: evaluation and effects. J Cancer Educ. 2008;23:80–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/08858190701821204.

Bozcuk H, Ozcan K, Erdogan C, Mutlu H, Demir M, Coskun S. A comparative study of art therapy in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and improvement in quality of life by watercolor painting. Complement Ther Med. 2017;30:67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2016.11.006.

Lee J, Choi MY, Kim YB, Sun J, Park EJ, Kim JH, Kang M, Koom WS. Art therapy based on appreciation of famous paintings and its effect on distress among cancer patients. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:707–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1473-5.

Meghani SH, Peterson C, Kaiser DH, Rhodes J, Rao H, Chittams J, Chatterjee A. A pilot study of a mindfulness-based art therapy intervention in outpatients with cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(9):1195–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909118760304.

Radl D, Vita M, Gerber N, Gracely EJ, Bradt J. The effects of Self-Book© art therapy on cancer-related distress in female cancer patients during active treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2018;27(9):2087–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4758.

Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P for the CONSORT NPT Group. CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):40–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-0046.

Higginson I, Evans CJ, Grande G, Preston N, Morgan M, McCrone P, Lewis P, Fayers P, Handing R, Hotopf M, Murray SA, Benalia H, Gysels M, Farquhar M, Todd C and on behalf of MORECare. Evaluating complex interventions in End-of-Life Care: the MORECare statement on good practice generated by a synthesis of transparent expert consultations and systematic reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11:111. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-111.

Solomon S, Lawlor K. Death anxiety: the challenge and the promise of whole person care. In: Hutchinson TA, editor. Whole person care. Montreal: Springer; 2011. p. 97–107.

Ganzel BL. Trauma-informed hospice and palliative care. Gerontologist. 2018;58(3):409–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw146.

Mount BM, Boston PH, Cohen SR. Healing connections: on moving from suffering to a sense of well-being. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(4):372–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.014.

Jacobs JM, Shaffer KM, Nipp RD, Fishbein JN, MacDonald J, El-Jawahri A, et al. Distress is interdependent in patients and caregivers with newly diagnosed incurable cancers. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(4):519–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-017-9875-3.

Winnicott DW. Playing and reality. London: Tavistock Publications; 1971.

Stroebe MS, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud. 1999;23(3):197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046.

Neimeyer RA. Meaning reconstruction & the experience of loss. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2001.

Arthur J, Sriram Yennurajalingam S, Nguyen L, Tanco K, Chisholm G, Hui D, Bruera E. The routine use of the Edmonton classification system for cancer pain in an outpatient supportive care center. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(5):1185–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951514001205.

Nainis NA. Approaches to art therapy for cancer inpatients: research and practice considerations. Art Ther. 2008;25(3):115–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2008.10129597.

Rhondali W, Lasserre E, Filbet M. Art therapy among palliative care inpatients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2012;27(6):571–2. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216312471413.

Wood M. Art therapy in palliative care. In: Pratt M, Wood M, editors. Art Therapy in Palliative Care: The Creative Response (1st ed.). London and New York: Routledge; 1998. pp. 226–37. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315788012.

Mount BM. Existential suffering and the determinants of healing. Eur J Palliat Care 2003, 10 (2) Supplement: 40–2.

Kearney M, Weininger R. Care of the soul. In: Cobb MR, Puchalski CM, Rumbold B, editors. Oxford textbook of spirituality in healthcare. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 273–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199571390.003.0038.

Ray A, Block SD, Friedlander RJ, Zhang B, Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG. Peaceful awareness in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(6):1359–68. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1359.

• Brenner KO, Rosenberg LB, Cramer MA, Jacobsen JC, Applebaum AJ, Block SD, et al. Exploring the psychological aspects of palliative care: lessons learned from an interdisciplinary seminar of experts. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(9):1274–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2021.0224. As a conceptual framework, this special interdisciplinary report describes the key psychological aspects that underlie optimal adaptive coping in palliative care patients, a central theme being the dialectic of living well while acknowledging dying.

Austin P, Mac LR. Finding peace in clinical settings: a narrative review of concept and practice. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15(4):490–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951516000924.

Arnold BL, Lloyd LS. Harnessing complex emergent metaphors for effective communication in palliative care: a multimodel perceptual analysis of hospice patients’reports of transcendence experiences. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(3):292–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113490821.

Collette N. Arteterapia en el final de la vida. (PhD dissertation) Departamento de Personalidad, Evaluación y Tratamientos psicológicos, Facultad de Psicología, Universitat de València, 2013. Available from https://www.educacion.gob.es/teseo/mostrarRef.do?ref=1042479

Collette N. Deepening the inner world. When art therapy meets spiritual needs. In: Wood MJ, Jacobson B, Cridford H, editors. The international handbook of art therapy in palliative and bereavement care (1st ed.) New York and London: Routledge; 2019. p. 3–16. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315110530.

•• Srolovitz M, Borgwardt J, Burkart M, Clements-Cortes A, Czamanski-Cohen J, Ortiz Guzman M, Hicks MG, Kaimal G, Lederman L, Potash JS, Yazdian Rubin S, Stafford D, Wibben A, Wood M, Youngwerth J, Jones CA, Kwok IB. Top ten tips palliative care clinicians should know about music and art therapy. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(1):135–44. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2021.0481. Art therapists, as increasingly available specialists for the palliative care teams, are advancing diverse and unique clinical services to effectively meet the holistic needs of patients with serious illnesses and their families.

Alvarez Bustins G. Retos metodológicos en la evaluación de la eficacia de la terapia manual [Methodological challenges in the evaluation of the effectiveness of manual therapy] (PhD dissertation). Departamento de Pediatría, de Obstetricia y Ginecología,y de Medicina Preventiva y Salud Pública. Facultad de Medicina, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. 2021.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348: g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687.

Howick J, Webster RK, Rees JL, Turner R, Macdonald H, Price A, et al. TIDieR-Placebo: a guide and checklist for reporting placebo and sham controls. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003294.

Kapitan L. Introduction to art therapy research. New York and London: Routledge; 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

NC was hired by the Hospital Sant Pau Research Institute through a grant from Fundación Mémora, which was not involved in the conduct of this review or the preparation of this article. The other co-authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

NC and AP are co-authors of one study with human subjects that has been included in this review. It was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the hospital, and all participants had provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Integrative Care

The original online version of this article was revised: The Figure 2 image is incorrect.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Collette, N., Sola, I., Bonfill, X. et al. Art Therapy in Advanced Cancer. A Mapping Review of the Evidence. Curr Oncol Rep 24, 1715–1730 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-022-01321-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-022-01321-0

Randomized controlled trial,

Randomized controlled trial,

Quasi-experimental pre-post study,

Quasi-experimental pre-post study,

Observational study,

Observational study,

Patients,

Patients,

Relatives

Relatives