Abstract

Purpose of Review

This article reviews current efforts to control bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users and outlines the opportunities and challenges to controlling STIs within HIV PrEP programs.

Recent Findings

The incidence of STIs continues to rise globally especially among HIV PrEP users, with an estimated 1 in 4 PrEP users having a curable bacterial STI. STIs and HIV comprise a syndemic needing dual interventions. The majority of STIs are asymptomatic, and when testing is available, many STIs occur in extragenital sites that are missed when relying on urine testing or genital swabs. Optimal testing and treatment, including testing for antimicrobial resistance, pose difficulties in high income countries and is essentially non-existent in most low- and middle-income countries. Novel STI primary prevention strategies, like doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for STI prevention, have proven to be highly efficacious in some populations. A few jurisdictions have issued normative guidelines and position statements for doxycycline PEP; however, clinical standards for implementation and data on public health impact are limited.

Summary

STI incidence rates are high and rising in sexually active populations. Sexual health programs should leverage the expansion of HIV PrEP delivery services to integrate STI testing, surveillance, and novel STI prevention services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a significant public health challenge worldwide with more than a million new cases of curable STIs, chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and syphilis, reported daily globally [1]. Untreated STIs can lead to sequelae, such as infertility, neurological injury, or chronic pain, which contribute to significant disability-adjusted life years lost, especially among cisgender women [2, 3]. The prevalence and incidence of STIs are especially high among people who are having condomless sex, many of whom are already using HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which provides protection against HIV but offers no protection against bacterial STIs [4,5,6]. A recent systematic review and metanalysis of studies among PrEP users from high income (HIC) and low-and-middle income countries (LMIC) reporting a combined outcome of chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis reported a prevalence of 23.9% and an incidence of 72.2 per 100 person years [7].

A resurgence of syphilis has also been reported across HICs and LMICs since the introduction of anti-retroviral therapy [8]. In HICs, the resurgence is mainly concentrated among specific populations such as men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women (TGW), and sex workers. There has also been a spike in syphilis cases among people who are unstably housed or in-housed in the US and increase of up to 300% in congenital syphilis in several places in countries like the US, Japan, and Brazil [9,10,11,12]. In LMICs, syphilis is still endemic in the general population, and the true burden may not be fully known as most data come from research conducted among women attending antenatal care [8, 13].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized the rising burden of STIs and called for integration of STI treatment and prevention services into HIV PrEP programs [14]. When PrEP was first made available for use by people at risk of acquiring HIV, there were concerns that there would be an accompanying increase in the frequency of condomless sex and the number of sex partners (or “sexual liberalization”) which would then lead to an increase in exposure to HIV and other STIs [15]. Early studies conducted after the roll-out of HIV PrEP suggested that HIV PrEP use was not associated with an increase in the number of condomless sex acts or increase in STI prevalence and incidence [5, 16]. Subsequent studies have, however, demonstrated a decrease in the use of condoms, an increase in the number of sex partners, and a high prevalence of bacterial STIs among people using PrEP [17,18,19,20]. It is also known that the prevalence and incidence of STIs were already on the rise before the advent of HIV PrEP, [21,22,23,24,25] and the high burden of STIs may not be fully accounted for by the introduction of HIV PrEP. Regardless of STI trends prior to or after introduction of HIV PrEP, it is clear that recommending condom use was insufficient HIV prevention strategy, and that people seeking PrEP face a high burden of STIs worldwide. The merits of HIV PrEP are now well established, and it is also unsurprising that there is a high prevalence of STIs among PrEP users, considering that a significant number of them rely on PrEP due to a lack of condom usage.

Testing and Treatment of STIs Within HIV PrEP Programs

Traditional strategies for control of STIs primarily rely on testing and treatment, [26] which requires sensitive diagnostics for both symptomatic and asymptomatic STIs followed by timely treatment.

STI testing is, however, largely unavailable—or inaccessible due to costs—in LMICs where the burden of STIs is greatest. In LMICs, symptom-based diagnosis and treatment of STIs (i.e., syndromic management) is currently the standard of care. This strategy misses asymptomatic infections, or approximately 70% of women with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. [27] In addition, most women with vaginal discharge have no C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae infection, [28, 29] and up to 30% of men with urethral discharge have no C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae. [26] Incorporating risk scores and basic laboratory procedures to clinical evaluation has had negligible impact on the predictive value of vaginal discharge for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infections [27, 30, 31]. For syphilis, many cases are asymptomatic repeat infections detected only by a four-fold rise in titers when using non-treponemal tests [32, 33]. This may prove difficult to detect especially in resource-limited settings relying on non-treponemal rapid point of care tests such as dual kits. Rapid tests which combine both treponemal and non-treponemal tests for active syphilis diagnosis in a single cartridge are now available and have the potential to improve diagnosis of active syphilis infection [34].

In resource-rich settings, quarterly molecular testing (and treatment) is the mainstay of chlamydia and gonorrhea control among people using PrEP [34]. An empirical study among MSM using PrEP has shown that implementing quarterly STI screening could effectively reduce the risk of asymptomatic STI exposure for a significant number of partners, leading to a decrease in transmission [35••]. However, there have also been concerns from modeling studies about the cost-effectiveness of quarterly testing due to the high costs of molecular tests especially for chlamydia and gonorrhea (particularly for cisgender MSM who experience fewer serious complications with less frequent testing) [36••]. There are also scientific implications like antibiotic resistance associated with more frequent use of antibiotics [37]. Importantly, the test and treat strategy faces the crucial problem of being reactive and inadequate in preventing the transmission of STIs, especially in populations with robust sexual networks.

Another important component of STI testing is to screen for STIs in extragenital sites, as STIs in such sites are often asymptomatic, difficult to treat, and can serve as reservoirs for uninterrupted transmission [38,39,40]. In LMICs, extragenital testing is rarely done as it is not part of routine care and the true burden of this is therefore not well known [41]. Detection of STIs at any site has been associated with increased chances of HIV acquisition [42, 43]. Screening for extragenital STIs regardless of symptoms should therefore be considered as part of routine STI testing. However, as there are non-pathogenic commensal Neisseria species present in extragenital sites such as the pharynx which can cross-react with some N. gonorrhoeae tests, it is important to consider confirmatory NAAT testing with more specific targets or tests with high (> 90%) positive predictive values [41, 44].

Primary STI Prevention

Primary STI prevention strategies have previously included recommendations like abstinence and consistent condom use. When utilized correctly and consistently, condoms provide high protection (more than 90%) against numerous STIs [45]. In real-world settings, condoms have proven to be ineffective, stigmatizing, and for some people, non-negotiable [46, 47].

Novel STI Prevention Strategies

Doxycycline Post-exposure Prophylaxis

Doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis is gaining prominence as a potential primary STI prevention strategy [48, 49]. Doxycycline is an inexpensive and widely available antibiotic with a strong safety profile. Doxycycline is first-line treatment for C. trachomatis and second-line treatment for syphilis; additionally, doxycycline has activity against N. gonorrhoeae in settings where tetracycline resistance is low.

Studies of cisgender men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TGW) in the US and France demonstrated that doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) effectively reduced incident STIs (chlamydia, syphilis, and gonorrhea) [50, 51]. In the French study (ANRS-IPERGAY), for instance, doxycycline PEP reduced the incidence of chlamydia and syphilis from 35.4 to 5.6 cases per 100 person years [50]. A recent pharmacologic study has demonstrated that a single 200-mg dose of doxycycline attained levels greater than three to four times the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for chlamydia and syphilis in vaginal tissue and six to nine times in rectal tissue, suggesting potential efficacy as PEP in both men and women [52••].

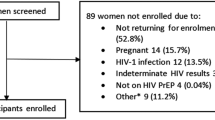

However, the only study of doxycycline PEP among cis-gender women in Kenya with a high STI burden showed no significant reduction in incident STIs, [53••] a significant variation from the findings of studies among cisgender men and transgender women. Postulated explanations for these findings include differences in anatomy, in antibiotic resistance patterns, and sub-optimal adherence [53••]. More recent findings from the study indicate low detection of doxycycline in objective measures of use from a subset of participants [54]. These findings suggest low use of doxycycline as a likely explanation for null results. Further studies are needed to evaluate efficacy of doxycycline PEP for STI prevention among people assigned female sex at birth. Additionally, it is crucial to understand the reasons for missed doses and non-use to ensure that interventions are acceptable and accessible.

The results of the doxycycline PEP trials have led to issuance of normative guidelines and position statements in several countries and public health departments to guide conversations between healthcare providers and their clients [35, 36, 55, 56].

The main concern for doxycycline use as PEP rather than solely as treatment includes selection for antibiotic resistance in STIs and other pathogenic and non-pathogenic organisms. A recent study has reported that doxycycline PEP reduced Staphylococcus aureus colonization by 16% without a significant increase in doxycycline resistant Staphylococcus aureus. There is also concern about disruption of the microbiome of people who are highly sexually active and use doxycycline PEP frequently; however, evidence from use of daily doxycycline for acne and malaria indicate that while doxycycline lowers microbiome diversity, it is recoverable during follow up [57]. The impact of intermittent yet frequent dosing—rather than daily dosing—is unknown. More studies on the most appropriate candidates for doxycycline PEP, its acceptability by different populations, and the clinical and policy readiness for integrating this promising strategy into HIV PrEP programs are needed.

Meningococcal Vaccine for Prevention of Gonorrhea

N. gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis have genetic similarities, and data from recent studies suggest that a meningitis vaccine might reduce gonorrhea transmission [58••]. The DoxyVac study in France is prospectively evaluating impact of a meningococcal vaccine (4CMenB) on reducing incidence rates of N. gonorrhoeae, with ongoing analyses on the level of protection [59••]. A vaccine against N. gonorrhoeae would be an important addition in the face of rising incidence and antimicrobial resistance. A modeling study has shown that it would be cost-effective to use a gonorrhea vaccine with moderate efficacy if it is offered to individuals at high risk of STIs or those already diagnosed with gonorrhea [60]. This suggests that even with moderate efficacy, it could still be cost-effective to offer a gonorrhea vaccine to PrEP users as they have both high incident cases and are risk of future STI acquisition.

Other Bacterial STIs

Mycobacterium genitalium

Mycoplasma genitalium (M. genitalium) is still associated with non-gonococcal urethritis, cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and infertility though it is thought to be less symptomatic than other bacterial STIs and its severity is debated [61, 62]. Among people in Europe and the US, the pooled prevalence of M. genitalium is more than 16% [63••]. Notably, 82.6% of the M. genitalium infections were macrolide-resistant and 14.3% were resistant to a fluoroquinolone.

Shigellosis

Shigellosis, a foodborne or waterborne infection endemic in LMICs, is also associated with sexually transmitted gastroenteritis with increasing prevalence among men who have sex with men (MSM), [64, 65] especially among people engaged in HIV care and HIV PrEP care [65, 66]. Among strains of Shigella in the US, Europe, and Asia, resistance to first line antibiotics for management and transcontinental spread has been reported [67]. As this spread is occurring among sexual networks with high prevalence of STIs such as chlamydia, syphilis, and gonorrhea, antibiotic treatment (and prophylaxis) for STIs is likely to exert selection pressure on strains of Shigella circulating in these sexual networks, threatening both individual clinical management and population level control [67].

Antimicrobial Resistance

In addition to rising rates of extreme drug resistant M. genitalium and Shigella spp., some strains of N. gonorrhoeae are now resistant to almost all classes of antibiotics including extended spectrum cephalosporins and azithromycin [39, 68]. This is a serious concern as N. gonorrhoeae is the second most common bacterial STI worldwide and its incidence is on an upward trajectory [63••]. Many NAAT tests do not detect AMR and there are no recommended tests for predicting treatment failure [69, 70]. Nonetheless, there are promising NAAT tests in development that can detect both N. gonorrhoeae and ciprofloxacin susceptibility, an important proof of concept [71]. New and cost effective antibiotics are also needed. Currently, there are new antimicrobial agents in phase III clinical trials with activity against N. gonorrhoeae, gepotidacin, and zoliflodacin [72,73,74]. Chlamydia and syphilis are still susceptible to their first-line therapies, even though concerns about development of antimicrobial resistance abound [75,76,77].

Opportunities for Integrating STI Prevention in HIV PrEP Programs

HIV PrEP delivery platforms still represent a unique opportunity for integrating and expanding STI prevention strategies alongside those for HIV prevention. People using HIV PrEP have already self-identified as being at risk of STIs and have made a step toward embracing prevention; hence, these platforms are natural settings to incorporate STI prevention services. The use of HIV PrEP involves navigating through side effects and adherence strategies, factors that can make strategies such as doxycycline PEP compatible among people with experience with HIV PrEP.

Renewed efforts are underway to expand the reach of HIV PrEP programs with the recent introduction of new HIV PrEP agents, such as the dapivirine vaginal ring and long-acting cabotegravir as well as the use of non-traditional HIV PrEP delivery platforms such as retail pharmacies, [78, 79] community settings [80,81,82], and telemedicine services to deliver HIV PrEP [83,84,85]. In recognition of barriers to accessing PrEP care, ongoing research is also being conducted on multi-purpose prevention tools (MPTs) [86]. MPTs simultaneously prevent HIV, other STIs, and/or unplanned pregnancy. All PrEP care models are opportune settings to improve access to interventions for sexual health with integrated STI testing, treatment, and prevention services.

Co-design and Participatory Community Research for HIV and STI Prevention

The incidence and prevalence of STIs varies widely among different populations even within similar geographical settings because of complex individual, social, and structural dynamics, such as access to education and healthcare, lack of trust in the healthcare system, socio-economic status, and racism [87,88,89]. It is therefore crucial that communities and populations that bear a disproportionate burden of STIs take part in designing interventions that are tailored to their unique circumstances [90].

Conclusion

The integration of STI prevention services within HIV PrEP delivery settings is inadequate given the rising rates of STIs. With STI prevention strategies like STI prophylaxis and novel HIV PrEP delivery models, integrated STI and HIV prevention is increasingly possible. As many STIs are asymptomatic and present in extra-genital sites, investment in multisite, asymptomatic STI testing (and antimicrobial resistance testing) is a crucial component of STI control. Primary prevention strategies, like doxycycline PEP and STI vaccines, represent potentially impactful and cost-effective strategies. Importantly, people working in the field of sexual health need to pro-actively adopt human-centered STI research designs to incorporate the priorities and preferences of the concerned communities.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Zhang J, Ma B, Han X, Ding S, Li Y. Global, regional, and national burdens of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years from 1990 to 2019: A trend analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Apr 2];6(11):763–76. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S235246422200219X/fulltext

Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet [Internet]. 2012 Dec 15 [cited 2023 Mar 31];380(9859):2197–223. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140673612616894/fulltext

Li Y, You S, Lee K, Yaesoubi R, Hsu K, Gift TL, et al. The estimated lifetime quality-adjusted life-years lost due to chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis in the United States in 2018. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2023 Apr 18 [cited 2023 Jun 6];227(8). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36806950/

Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, Baggaley R, O’Reilly KR, Koechlin FM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS [Internet]. 2016 Jul 7 [cited 2023 Mar 22];30(12):1973. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4949005/

Molina J-M, Capitant C, Spire B, Pialoux G, Cotte L, Charreau I, et al. On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2015 Dec 3 [cited 2023 Mar 23];373(23):2237–46. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1506273

Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2012 Aug 2 [cited 2023 Mar 23];367(5):399–410. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1108524

Ong JJ, Baggaley RC, Wi TE, Tucker JD, Fu H, Smith MK, et al. Global epidemiologic characteristics of sexually transmitted infections among individuals using preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2019 Dec 13 [cited 2023 Mar 25];2(12). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6991203/

Kenyon CR, Osbak K, Tsoumanis A. The global epidemiology of syphilis in the past century – A systematic review based on antenatal syphilis prevalence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2016 May 11 [cited 2023 Jun 15];10(5). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4864207/

Tripathy DM, Gupta S, Vasudevan B. Resurgence of syphilis, the great imitator. Med J Armed Forces India. 2022;78(2):131–5.

Ramchandani MS, Cannon CA, Marra CM. Syphilis: A modern resurgence. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2023;37(2):195–222.

Schmidt R, Carson PJ, Jansen RJ. Resurgence of syphilis in the United States: An assessment of contributing factors. Infect Dis (Auckl) [Internet]. 2019 Jan [cited 2023 Jul 4];12:117863371988328. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6798162/

Dos Santos MM, Lopes AKB, Roncalli AG, De Lima KC. Trends of syphilis in Brazil: A growth portrait of the treponemic epidemic. PLoS One [Internet]. 2020 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Jul 4];15(4). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7145144/

Kojima N, Klausner JD. An update on the global epidemiology of syphilis. Curr Epidemiol reports [Internet]. 2018 Mar [cited 2023 Jun 15];5(1):24. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6089383/

WHO implementation tool for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV infection: Module 1: Clinical [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 31]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255889

Blumenthal J, Haubrich RH. Will risk compensation accompany pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV? Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(11):909–15.

McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): Effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet [Internet]. 2016 Jan 2 [cited 2023 Mar 23];387(10013):53–60. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140673615000562/fulltext

Traeger MW, Schroeder SE, Wright EJ, Hellard ME, Cornelisse VJ, Doyle JS, et al. Effects of pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus infection on sexual risk behavior in men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2018 Aug 16 [cited 2023 Mar 23];67(5):676–86. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/67/5/676/4917600

Hoornenborg E, Coyer L, Achterbergh RCA, Matser A, Schim van der Loeff MF, Boyd A, et al. Sexual behaviour and incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men using daily and event-driven pre-exposure prophylaxis in AMPrEP: 2 year results from a demonstration study. Lancet HIV [Internet]. 2019 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Mar 23];6(7):e447–55. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S2352301819301365/fulltext

Zablotska IB, Vaccher SJ, Bloch M, Carr A, Foster R, Grulich A, et al. High adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and no HIV seroconversions despite high levels of risk behaviour and STIs: The Australian demonstration study PrELUDE. AIDS Behav [Internet]. 2019 Jul 15 [cited 2023 Mar 23];23(7):1780–9. Available from: https://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/article/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2290-3

Montaño MA, Dombrowski JC, Dasgupta S, Golden MR, Duerr A, Manhart LE, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and STI diagnoses among MSM initiating PrEP in a clinic setting. AIDS Behav [Internet]. 2019 Feb 15 [cited 2023 Mar 24];23(2):548. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6368873/

Disease data from ECDC Surveillance Atlas - Syphilis [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/syphilis/surveillance-and-disease-data/disease-data-atlas

STD data and statistics [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/default.htm

Traeger MW, Cornelisse VJ, Asselin J, Price B, Roth NJ, Willcox J, et al. Association of HIV preexposure prophylaxis with incidence of sexually transmitted infections among individuals at high risk of HIV infection. JAMA [Internet]. 2019 Apr 4 [cited 2023 Mar 24];321(14):1380. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6459111/

Beymer MR, DeVost MA, Weiss RE, Dierst-Davies R, Shover CL, Landovitz RJ, et al. Does HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use lead to a higher incidence of sexually transmitted infections? A case-crossover study of men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, California. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2018 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Mar 23];94(6):457–62. Available from: https://sti.bmj.com/content/94/6/457

Nguyen VK, Greenwald ZR, Trottier H, Cadieux M, Goyette A, Beauchemin M, et al. Incidence of sexually transmitted infections before and after preexposure prophylaxis for HIV. AIDS [Internet]. 2018 Feb 20 [cited 2023 Mar 23];32(4):523–30. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Fulltext/2018/02200/Incidence_of_sexually_transmitted_infections.13.aspx

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the management of symptomatic sexually transmitted infections. :201.

Zemouri C, Wi TE, Kiarie J, Seuc A, Mogasale V, Latif A, et al. The performance of the vaginal discharge syndromic management in treating vaginal and cervical infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Mar 31];11(10):e0163365. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163365

Peeling RW, Mabey D, Herring A, Hook EW. Why do we need quality-assured diagnostic tests for sexually transmitted infections? Nat Rev Microbiol 2006 412 [Internet]. 2006 Dec [cited 2023 Mar 31];4(12):S7–19. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrmicro1569

Otieno FO, Ndivo R, Oswago S, Ondiek J, Pals S, McLellan-Lemal E, et al. Evaluation of syndromic management of sexually transmitted infections within the Kisumu Incidence Cohort Study. Int J STD AIDS [Internet]. 2014 Oct 13 [cited 2023 Jun 7];25(12):851. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4586058/

Pettifor A, Walsh J, Wilkins V, Raghunathan P. How effective is syndromic management of STDs?: A review of current studies. Sex Transm Dis [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2023 Mar 31];27(7):371–85. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10949428/

Van Gemert C, Hellard M, Bradshaw CS, Fowkes FJI, Agius PA, Stoove M, et al. Syndromic management of sexually transmissible infections in resource-poor settings: A systematic review with meta-analysis of the abnormal vaginal discharge flowchart for Neisseria gonorrhoea and Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Health [Internet]. 2017 Aug 25 [cited 2023 Mar 31];15(1):1–12. Available from: https://www.publish.csiro.au/sh/SH17070

Repeat syphilis infections in men who have sex with men, 2000–2005, Chicago, IL [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 15]. Available from: https://cdc.confex.com/cdc/std2006/techprogram/P10609.HTM

Kenyon C, Osbak KK, Apers L. Repeat syphilis is more likely to be asymptomatic in HIV-infected individuals: A retrospective cohort analysis with important implications for screening. Open Forum Infect Dis [Internet]. 2018 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Jun 15];5(6). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6016412/

WHO PrEP implementation tool [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tools/prep-implementation-tool

•• Tang EC, Vittinghoff E, Philip SS, Doblecki-Lewis S, Bacon O, Chege W, et al. Quarterly screening optimizes detection of sexually transmitted infections when prescribing HIV preexposure prophylaxis. AIDS [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Jun 7];34(8):1181–6. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Fulltext/2020/07010/Quarterly_screening_optimizes_detection_of.9.aspx

•• Van Wifferen F, Hoornenborg E, Schim Van Der Loeff MF, Heijne J, Van Hoek AJ. Cost-effectiveness of two screening strategies for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae as part of the PrEP programme in the Netherlands: A modelling study. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Jun 7];97(8):607–12. Available from: https://sti.bmj.com/content/97/8/607

Jongen VW, Zimmermann HML, Goedhart M, Bogaards JA, Davidovich U, Coyer L, et al. Can we screen less frequently for STI among PrEP users? Assessing the effect of biannual STI screening on timing of diagnosis and transmission risk in the AMPrEP Study. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2022 May 18 [cited 2023 Apr 3];0:1–7. Available from: https://sti.bmj.com/content/early/2022/05/17/sextrans-2022-055439

Jansen K, Steffen G, Potthoff A, Schuppe AK, Beer D, Jessen H, et al. STI in times of PrEP: High prevalence of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and mycoplasma at different anatomic sites in men who have sex with men in Germany. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Feb 7 [cited 2023 Apr 6];20(1). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7007644/

•• Radovanovic M, Kekic D, Jovicevic M, Kabic J, Gajic I, Opavski N, et al. Current susceptibility surveillance and distribution of antimicrobial resistance in N. gonorrheae within WHO regions. Pathogens [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Apr 7];11(11). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9697523/

Patton ME, Kidd S, Llata E, Stenger M, Braxton J, Asbel L, et al. Extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydia testing and infection among men who have sex with men—STD Surveillance Network, United States, 2010–2012. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Jun 7];58(11):1564–70. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu184

Quilter laura S, Obondi eve, Kunzweiler colin, Okall D, Bailey robert, Djomand gaston, et al. Prevalence and correlates of and a risk score to identify asymptomatic anorectal gonorrhoea and chlamydia infection among men who have sex with men in Kisumu, Kenya. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Jul 3];95:201–11. Available from: http://sti.bmj.com/

Cohen MS. Sexually transmitted diseases enhance HIV transmission: No longer a hypothesis. Lancet (London, England) [Internet]. 1998 [cited 2023 Apr 6];351 Suppl 3(SUPPL.3):5–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9652712/

Koedijk FDH, van Bergen JEAM, Dukers-Muijrers NHTM, van Leeuwen AP, Hoebe CJPA, van der Sande MAB. The value of testing multiple anatomic sites for gonorrhoea and chlamydia in sexually transmitted infection centres in the Netherlands, 2006–2010. Int J STD AIDS [Internet]. 2012 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Apr 6];23(9):626–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23033514/

Papp JR, Schachter J, Gaydos CA, Van Der Pol B. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae — 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep [Internet]. 2014 Mar 3 [cited 2023 Jul 3];63(0):1. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4047970/

Marfatia Y, Pandya I, Mehta K. Condoms: Past, present, and future. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS [Internet]. 2015 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Jun 7];36(2):133. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4660551/

Schwartz RM, Bruno DM, Augenbraun MA, Hogben M, Joseph MA, Liddon N, et al. Perceived financial need and sexual risk behavior among urban, minority patients following sexually transmitted infection diagnosis. Sex Transm Dis [Internet]. 2011 Mar [cited 2023 Apr 2];38(3):230–4. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/stdjournal/Fulltext/2011/03000/Perceived_Financial_Need_and_Sexual_Risk_Behavior.16.aspx

Stewart J, Bukusi E, Celum C, Delany-Moretlwe S, Baeten JM. Sexually transmitted infections among African women: An underrecognized epidemic and an opportunity for combination STI/HIV prevention. AIDS [Internet]. 2020 Apr 4 [cited 2023 Apr 2];34(5):651. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7290066/

Grant JS, Stafylis C, Celum C, Grennan T, Haire B, Kaldor J, et al. Doxycycline prophylaxis for bacterial sexually transmitted infections. Clin Infect Dis An Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am [Internet]. 2020 Mar 3 [cited 2023 Mar 24];70(6):1247. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7319058/

Stewart J, Bukusi E, Sesay FA, Oware K, Donnell D, Soge OO, et al. Doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis for prevention of sexually transmitted infections among Kenyan women using HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: Study protocol for an open-label randomized trial. Trials [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Apr 3];23(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35710444/

Molina JM, Charreau I, Chidiac C, Pialoux G, Cua E, Delaugerre C, et al. Post-exposure prophylaxis with doxycycline to prevent sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men: an open-label randomised substudy of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2018 Mar 1 [cited 2023 Apr 2];18(3):308–17. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S1473309917307259/fulltext

Luetkemeyer A, Dombrowski J, Cohen S, Donnell D, Grabow C, Brown C, et al. Doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis for prevention of STIs among MSM and TGW who are living with HIV or on PrEP co-chairs choice. [cited 2023 Apr 2]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2020

•• Mucosal pharmacology of doxycycline for bacterial STI prevention in men and women [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 2]. Available from: https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/mucosal-pharmacology-of-doxycycline-for-bacterial-sti-prevention-in-men-and-women/

•• Doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis for prevention of STIs among cisgender women [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 2]. Available from: https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/doxycycline-postexposure-prophylaxis-for-prevention-of-stis-among-cisgender-women/

Full schedule [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 23]. Available from: https://stihiv2023.eventscribe.net/agenda.asp?pfp=days&day=7/25/2023&theday=Tuesday&h=Tuesday July 25&BCFO=P%7CG

Update S. Health update doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis reduces incidence of sexually transmitted infections. 2022;

Gandhi RT, Bedimo R, Hoy JF, Landovitz RJ, Smith DM, Eaton EF, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2022 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA panel. JAMA [Internet]. 2023 Jan 3 [cited 2023 Apr 3];329(1):63–84. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2799240

Haas K, Notay M, Rodriguez W, Rolston M, Clark A, Burney W, et al. 383 Doxycycline effects on the gut and skin microbiomes and lipidome in acne. J Invest Dermatol [Internet]. 2018 May 1 [cited 2023 Jun 19];138(5):S65. Available from: http://www.jidonline.org/article/S0022202X18306158/fulltext

•• Bruxvoort KJ, Lewnard JA, Chen LH, Tseng HF, Chang J, Veltman J, et al. Prevention of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with meningococcal B vaccine: A matched cohort study in Southern California. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2023 Feb 8 [cited 2023 Apr 2];76(3):e1341–9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/76/3/e1341/6596517

•• Luetkemeyer AF, Donnell D, Dombrowski JC, Cohen S, Grabow C, Brown CE, et al. ANRS DOXYVAC: Final analysis may modify interim results of this trial assessing the effectiveness of meningococcal B vaccination in preventing gonococcal infections | EATG. https://www.eatg.org/ [Internet]. 2023 Apr 6 [cited 2023 May 24];388(14):1296–306. Available from: https://www.eatg.org/hiv-news/anrs-doxyvac-final-analysis-may-modify-interim-results-of-this-trial-assessing-the-effectiveness-of-meningococcal-b-vaccination-in-preventing-gonococcal-infections/

Whittles LK, Didelot X, White PJ. Public health impact and cost-effectiveness of gonorrhoea vaccination: An integrated transmission-dynamic health-economic modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Jul 7];22(7):1030–41. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S1473309921007441/fulltext

Ona S, Molina RL, Diouf K. Mycoplasma genitalium: An overlooked sexually transmitted pathogen in women? Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2016;2016.

Peel J, Aung E, Bond S, Bradshaw C. Recent advances in understanding and combatting Mycoplasma genitalium. Fac Rev. 2020;30:9.

•• Sokoll PR, Migliavaca CB, Siebert U, Schmid D, Arvandi M. Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium infection among HIV PrEP users: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2023 Feb 20 [cited 2023 Mar 31];0:1–9. Available from: https://sti.bmj.com/content/early/2023/02/19/sextrans-2022-055687

Troeger C, Forouzanfar M, Rao PC, Khalil I, Brown A, Reiner RC, et al. Estimates of global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoeal diseases: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2017 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Jun 20];17(9):909. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5589208/

Braam JF, Bruisten SM, Hoogeland M, de Vries HJC, Schim van der Loeff MF, van Dam AP. Shigella is common in symptomatic and asymptomatic men who have sex with men visiting a sexual health clinic in Amsterdam. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Jun 20];98(8):564–9. Available from: https://sti.bmj.com/content/98/8/564

Newman KL, Newman GS, Cybulski RJ, Fang FC. Gastroenteritis in men who have sex with men in Seattle, Washington, 2017–2018. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Jul 5];71(1):109–15. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31621824/

Baker KS, Dallman TJ, Ashton PM, Day M, Hughes G, Crook PD, et al. Intercontinental dissemination of azithromycin-resistant shigellosis through sexual transmission: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 Jun 20];15:913–21.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00002-X

Chan PA, Robinette A, Montgomery M, Almonte A, Cu-Uvin S, Lonks JR, et al. Extragenital infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: A review of the literature. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2023 Apr 7];2016. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27366021/

Whiley DM, Tapsall JW, Sloots TP. Nucleic acid amplification testing for Neisseria gonorrhoeae: An ongoing challenge. J Mol Diagnostics [Internet]. 2006 Feb 1 [cited 2023 Jul 3];8(1):3–15. Available from: http://www.jmdjournal.org/article/S1525157810602875/fulltext

World Health Organization. Reproductive health and research. WHO guidelines for the treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. :55.

Murtagh MM. The point-of-care diagnostic landscape for sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Sánchez-Busó L, Cole MJ, Spiteri G, Day M, Jacobsson S, Golparian D, et al. Europe-wide expansion and eradication of multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae lineages: A genomic surveillance study. The Lancet Microbe [Internet]. 2022 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Apr 7];3(6):e452–63. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35659907/

Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Scangarella-Oman N, Unemo M. In vitro activity of the novel triazaacenaphthylene gepotidacin (GSK2140944) against MDR Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Antimicrob Chemother [Internet]. 2018 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Apr 7];73(8):2072–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29796611/

Scangarella-Oman NE, Hossain M, Dixon PB, Ingraham K, Min S, Tiffany CA, et al. Microbiological analysis from a phase 2 randomized study in adults evaluating single oral doses of gepotidacin in the treatment of uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhea caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet]. 2018 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Apr 7];62(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30249694/

Wanninger S, Donati M, Di Francesco A, Hässig M, Hoffmann K, Seth-Smith HMB, et al. Selective pressure promotes tetracycline resistance of Chlamydia suis in fattening pigs. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016 Nov 1 [cited 2023 May 24];11(11). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27893834/

Sandoz KM, Rockey DD. Antibiotic resistance in Chlamydiae. Future Microbiol [Internet]. 2010 Sep [cited 2023 May 24];5(9):1427. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3075073/

Stamm L V. Syphilis: Antibiotic treatment and resistance. Epidemiol Infect [Internet]. 2015 Mar 15 [cited 2023 May 24];143(8):1567–74. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25358292/

Pintye J, Odoyo J, Nyerere B, Achieng P, Araka E, Omondi C, et al. Nurse-facilitated preexposure prophylaxis delivery for adolescent girls and young women seeking contraception at retail pharmacies in Kisumu, Kenya. AIDS [Internet]. 2023 Mar 3 [cited 2023 Mar 29];37(4):617. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9974532/

Ortblad KF, Mogere P, Roche S, Kamolloh K, Odoyo J, Irungu E, et al. Design of a care pathway for pharmacy-based PrEP delivery in Kenya: Results from a collaborative stakeholder consultation. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2020 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Mar 29];20(1):1–9. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05898-9

Barnabas R V., Szpiro AA, van Rooyen H, Asiimwe S, Pillay D, Ware NC, et al. Community-based antiretroviral therapy versus standard clinic-based services for HIV in South Africa and Uganda (DO ART): A randomised trial. Lancet Glob Heal [Internet]. 2020 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Jul 4];8(10):e1305–15. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S2214109X20303132/fulltext

Stewart J, Stadeli KM, Green ML, Etter-Carlson L, Dahl E, Davidson GH, et al. A co-located continuity clinic model to address healthcare needs of women living unhoused with opioid use disorder, who engage in transactional sex in north Seattle. Sex Transm Dis [Internet]. 2020 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Jul 4];47(1):e5. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6923540/

Grammatico MA, Moll AP, Choi K, Springer SA, Shenoi S V. Feasibility of a community-based delivery model for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among bar patrons in rural South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc [Internet]. 2021 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Jul 3];24(11). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34826363/

Cao B, Bao H, Oppong E, Feng S, Smith KM, Tucker JD, et al. Digital health for sexually transmitted infection and HIV services: A global scoping review. Curr Opin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2023 Jul 4];33(1):44–50. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31789695/

Hoagland B, Torres TS, Bezerra DRB, Geraldo K, Pimenta C, Veloso VG, et al. Telemedicine as a tool for PrEP delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic in a large HIV prevention service in Rio de Janeiro-Brazil. Brazilian J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2021 May 7];24(4):360–4. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7261432/

Rousseau E, Julies RF, Madubela N, Kassim S. Novel platforms for biomedical HIV prevention delivery to key populations - Community mobile clinics, peer-supported, pharmacy-led PrEP delivery, and the use of telemedicine. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Apr 6];18(6):500–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34708316/

Young Holt B, Turpin JA, Romano J. Multipurpose prevention technologies: Opportunities and challenges to ensure advancement of the most promising MPTs. Front Reprod Heal. 2021;6:3.

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs): Annual data tables - GOV.UK [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/sexually-transmitted-infections-stis-annual-data-tables

•• McCuistian C, Peteet B, Burlew K, Jacquez F. Sexual health interventions for racial/ethnic minorities using community-based participatory research: A systematic review. Health Educ Behav [Internet]. 2023 Feb 1 [cited 2023 Apr 6];50(1):107. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9004606/

Woode Owusu M, Estupiñán Fdez. De Mesa M, Mohammed H, Gerressu M, Hughes G, Mercer CH. Race to address sexual health inequalities among people of Black Caribbean heritage: Could co-production lead to more culturally appropriate guidance and practice? Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2023 May 3 [cited 2023 Jul 4];0(0). Available from: https://sti.bmj.com/content/early/2023/05/02/sextrans-2023-055798

Tucker JD, Tang W, Li H, Liu C, Fu R, Tang S, et al. Crowdsourcing designathon: A new model for multisectoral collaboration. BMJ Innov [Internet]. 2018 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Mar 29];4(2):46–50. Available from: https://innovations.bmj.com/content/4/2/46

Cornelisse VJ, Ong JJ, Ryder N, Ooi C, Wong A, Kenchington P, et al. Interim position statement on doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (Doxy-PEP) for the prevention of bacterial sexually transmissible infections in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand – The Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine (ASHM). Sex Health [Internet]. 2023 Mar 17 [cited 2023 Apr 3]; Available from: https://www.publish.csiro.au/sh/SH23011

Kohli M, Medland N, Fifer H, Saunders J. BASHH updated position statement on doxycycline as prophylaxis for sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2022 May 1 [cited 2023 Apr 3];98(3):235–6. Available from: https://sti.bmj.com/content/98/3/235

Funding

US National Institute of Health Grants R01AI45971 and K23MH124466.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Elizabeth Bukusi has received honoraria for speaker bureau/scientific advisory board from Merck and ViiV. The other authors declare competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mogaka, F.O., Stewart, J., Omollo, V. et al. Challenges and Solutions to STI Control in the Era of HIV and STI Prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 20, 312–319 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-023-00666-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-023-00666-w