Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review aims to (1) conceptualize the complexity of the opioid use disorder epidemic using a conceptual model grounded in the disease continuum and corresponding levels of prevention and (2) summarize a select set of interventions for the prevention and treatment of opioid use disorder.

Recent Findings

Epidemiologic data indicate non-medical prescription and illicit opioid use have reached unprecedented levels, fueling an opioid use disorder epidemic in the USA. A problem of this magnitude is rooted in multiple supply- and demand-side drivers, the combined effect of which outweighs current prevention and treatment efforts. Multiple primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention interventions, both evidence-informed and evidence-based, are available to address each point along the disease continuum—non-use, initiation, dependence, addiction, and death.

Summary

If interventions grounded in the best available evidence are disseminated and implemented across the disease continuum in a coordinated and collaborative manner, public health systems could be increasingly effective in responding to the epidemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Opioid use disorder, often secondary to non-medical use of prescription opioids (NMUPO), is a leading public health issue in the USA, and one of such scale it has been called an epidemic [1,2,3,4]. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), non-medical use refers to “the use of a medication without a prescription, in a way other than as prescribed, or for the experience or feelings elicited” [5]. Since 1979, the overdose death rate in the USA has grown exponentially, increasing at a rate of 9% each year and doubling at a rate of every 8 years [6]. In 2014, an estimated 4.3 million individuals 12 years of age or older reported current NMUPO, with 1.9 million individuals meeting the criteria for abuse or dependence in the past year [7]. Moreover, the share of substance abuse treatment admissions for primary non-heroin opiates roughly tripled from 3% in 2003 to 9% in 2013 [8]. Among infants, neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), a drug-withdrawal syndrome often resulting from prenatal opioid exposure, has nearly quadrupled from 7 to 27 cases per 1000 neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions from 2004 through 2013 [9]. Given the staggering trends, opioid use disorder and its consequences have rapidly climbed to a level that has alarmed the nation. The current epidemic is the likely result of a surge of marketing, prescribing, dispensing, and consumption of prescription narcotics that began two decades ago, much of which was diverted for non-medical use [2]. To understand interventions for the epidemic, it is first necessary to understand drivers of NMUPO.

Drivers of Non-Medical Use of Prescription Opioids

NMUPO results from a complex, cumulative interaction of multiple drivers. At its core, however, is a copious supply of prescription opioids, including those used for the treatment of pain and those, like buprenorphine, used for the treatment of addiction. Prescription opioid sales have quadrupled since 1999, concurrent with increases in prescription opioid-related treatment admissions and overdose deaths [10]. The prescription opioid supply is most immediately a function of the prescribing/dispensing practices of health care providers. In 2012, health care providers wrote an estimated 259 million prescriptions for opioids, equating to one prescription per American adult [11]. At the state level, opioid prescribing rates vary considerably, ranging from a high of roughly 143 prescriptions per 100 persons to a low of 52 prescriptions per 100 persons [12]. Variability in opioid prescribing has been tied to variability in rates of NMUPO and overdose deaths among states [10]. For example, 21 of 27 (77.8%) states with overdose death rates above the national rate were also found to have prescription opioid sales rates that exceeded the national rate [10].

It is important, however, to make a finer distinction between the “supply” of prescription opioids and the “source.” The supply of legitimate prescription opioids, among several classes of controlled substances, is a function of a federally regulated system of quotas obtained and sometimes traded by pharmaceutical manufacturers. These quotas, and thus the supply, have steadily increased with demand, driven by effective marketing of the products to professionals, governmental and non-governmental entities, regulatory bodies, and directly to the public [2, 13, 14]. In turn, an unprecedented supply has been available to be prescribed and dispensed as federally approved safe and effective medications through historically trusted and legitimate sources.

The surge in prescribing/dispensing and consumption of prescription opioids has its origin in the 1980s and 1990s, a period characterized by calls to address untreated pain and for greater use of prescription opioids to treat pain, especially non-cancer chronic pain [2, 13]. The American Pain Society put forth “pain as the fifth vital sign,” which elevated the importance of pain assessment to equal that of established vital signs and urged physicians to respond to patient pain [2, 15, 16]. Multiple professional organizations, patient advocacy groups, and others also advocated for a more proactive approach to pain management, with an emphasis on prescription opioids as the remedy [2, 16]. Highly intertwined with the shift toward more aggressive use of prescription opioids was the introduction of OxyContin® by Purdue Pharma, an event accompanied by resource-intensive marketing and education to promote it, and prescription opioids in general, to health care providers and patients [2, 13]. The activities of Purdue Pharma and other companies understated the risk of addiction and overstated the advantages of prescription opioids, a tactic that facilitated broad uptake of prescription opioids in the medical community [2, 13]. The pharmaceutical industry has thrived on the uptake, a factor that underlies the epidemic gripping the nation [13, 14].

Compared to illicit drugs like heroin or cocaine, prescription opioids present a distinct, yet dangerous risk to public health [1, 13]. Nevertheless, they have often been considered safer to abuse than their illicit counterparts, in part because they can be legally obtained, possess legitimate medical indications, and are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration [1, 17]. From an epidemiological standpoint, evidence also suggests that low perceptions of risk/harm as well as parental and peer approval, among other risk factors, are associated with non-medical use [18]. Notably, most individuals (53%) obtain prescription opioids for non-medical use free from friends or family, over 80% of whom obtained them from one prescriber [19]. While these risk factors likely represent key drivers of NMUPO, it is also important to recognize that they are amenable to change.

Despite NMUPO reaching epidemic levels, a socio-cultural environment of stigma remains a formidable driver and a barrier to an optimal response. Stigma and discrimination toward individuals with mental illness and addiction are prevalent, a troubling reality as it can hinder help-seeking behaviors, the availability of treatment and other support, and perhaps the implementation of interventions across all levels of prevention [20, 21]. Public views have even been found to be more negative toward individuals with drug addiction as compared to those with mental illness [22]. For example, when compared to other mental illness, individuals have indicated greater acceptance of discriminatory practices against those with addiction, greater skepticism of the effectiveness of addiction treatments, and greater opposition toward policies to assist those with addiction [22]. In addition, misperceptions of addiction as a moral failing, a weakness, or a choice, rather than a chronic, relapsing disease endure [23]. Stigma similarly surrounds evidence-based strategies critical for curbing the growing public health burden of the epidemic. Its association with opioid overdose reversal drugs (e.g., naloxone) and medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid addiction is especially concerning as it challenges adequate access to and use of these life-saving strategies [24, 25]. Thus, stigma, whether toward addiction or toward strategies aimed at alleviating its harms, can foster a socio-cultural environment unsupportive of responding to NMUPO, thereby perpetuating the problem.

These drivers—market forces, misguided policy, perceptions of risk, and stigma—serve as a backdrop to the complexity of addressing NMUPO, and ultimately opioid use disorder, as a public health problem. Presently, prevention and treatment efforts are greatly outweighed by the combined effect of these drivers as evidenced by multiple public health markers: (1) non-heroin opiate-related treatment admissions [8], (2) overdose deaths [27], and (3) progression to heroin among a sub-group of individuals with a history of NMUPO [26]. In the end, neither a single nor a simple solution will solve such a complex public health problem.

Opioid use disorder, and other substance use disorder that results in injection drug use, has always been a key factor in transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus, and other blood borne pathogens. Lack of availability of safe syringes to use for injection, and an ever-increasing demand and use of prescribed and illicit opioids, has resulted in a new surge in needle sharing among those with opioid use disorder. There are recent rapid increases in hepatitis C and at least one alarming spike in HIV has been reported in the rural Midwest [28]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with state and local organizations in the state, successfully deployed a rapid intervention to halt the epidemic. They learned that the more than 200 new cases of HIV were largely the result of sharing needles to inject diverted or prescribed opioids among a large network of users, many sharing needles that were re-used dozens of times between users [28, 29]. Best practices for syringe services programs are reviewed elsewhere in this issue and will not be reviewed herein. The purpose of this work is to conceptualize the opioid use disorder epidemic and frame it against promising and proven interventions.

Methods

To identify the targeted strategies, we examined the English language literature for evidence to support the intervention strategies recommended herein, with an emphasis on randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and reviews of reviews when possible. Many of the identified studies and reviews were conducted in the past 15 years. The recommended intervention strategies are thus not only current, but many are supported by at least the quality of evidence consistent with randomized controlled trials. Nevertheless, there are other potential interventions that could be recommended to address the epidemic. We, however, restricted the set of interventions described herein for brevity and parsimony.

Results

A Conceptual Model to Guide a Comprehensive Response

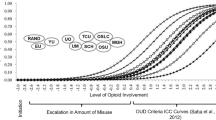

Below, we propose a conceptual model that simultaneously illustrates the complexity of the problem and offers a roadmap of evidence-informed and evidence-based strategies to address it (Fig. 1 ). The continuum of the disease of addiction, from non-use to dependence, addiction, and ultimately, premature death, is central to the model. Targeted public health strategies need to be brought to bear against different points all along the disease continuum for measurable progress to be made against the epidemic.

The three levels of prevention—primary, secondary, and tertiary—are placed along the disease continuum. Eight evidence-informed and evidence-based strategies encompassing all three levels of prevention have then been strategically positioned along the disease continuum (summary in Table 1 .). By engaging in these strategies at once, disseminating and implementing best practices in high-risk communities and target populations, we posit that public health systems will be increasingly effective in combating the problem. In addition to the disease continuum being central to the model, we also advocate for an approach grounded in dissemination and implementation science. In other words, there are promising and evidence-based tools available to address each point along the disease continuum, leaving no time to spare in disseminating, implementing, and evaluating them.

Primary Prevention

Dissemination and Implementation of Prevention Programs

Primary prevention aims to prevent the development of a disease, and addiction is a preventable disease [23, 96]. Preventing the initiation of NMUPO or any illicit opioid should be the highest goal. The dissemination and implementation of effective, evidence-based prevention programs to decrease risk factors and increase protective factors for NMUPO across developmental periods is critical [30]. They can be delivered in various settings (e.g., homes and schools) and target diverse populations. On a population level, risk for substance abuse can be used to stratify target populations and to deliver prevention strategies that more effectively meet their needs [30]. Moreover, prevention programs can be conceptualized by a three-tiered typology—universal, selected, and indicated—reflecting increasing levels of risk [30, 31]. Tailoring prevention programs to the attributes of target populations and making them culturally relevant could also augment their effectiveness and facilitate acceptance, implementation, and sustainability in community settings [31, 97]. For maximum public health impact, prevention programs seeking to prevent or delay the initiation of substance abuse among children and youth may be especially important since individuals with a substance use disorder often initiate before they are 18 years of age [31, 98].

Evidence demonstrating the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of prevention programs continues to grow. Prevention and promotion programs can generate significant, sustainable reductions in multiple problem outcomes, including substance use, among children and young people [32••]. With regard to prescription drugs specifically, evidence suggests that prevention programs can reduce non-medical use. For example, findings from three randomized controlled trials indicate that brief, universal prevention interventions implemented in early adolescence can decrease non-medical use, including NMUPO, in late adolescence and young adulthood [33]. As for the economic implications, effective school-based programs implemented nationwide, for example, could result in an estimated 18 dollars saved for each dollar invested [99]. Simply put, “prevention works” and is a high value proposition [100].

A fundamental risk factor for NMUPO centers on access to prescription opioids, whether through retail outlets, social sources, or other avenues. National data indicate social access is particularly problematic since most individuals obtain prescription opioids for non-medical use from friends or family [19]. Consequently, primary prevention initiatives focused on safe storage and disposal of prescription opioids are one strategy for reducing social access [1], though one for which randomized controlled trials of effectiveness do not yet exist. In Utah, for example, a statewide media campaign targeted adults to promote safe use, storage, and disposal [34]. In a post-campaign survey, 18% of respondents reported medication disposal because of the campaign, and those reporting use of a drop box or collection event for disposal increased from < 1 to 5.4% [34, 101]. In Tennessee, an analysis of permanent drug donation box collections found that 4.9% of the collected pharmaceutical waste were controlled substances, which suggests that permanent drug donation boxes can effectively eliminate controlled substances from community settings [35]. Thus, a variety of primary prevention initiatives hold significant promise for lessening the volume of prescription opioids accessible for non-medical use.

Health Professions Training and Continuing Education

Health care providers occupy a central role in the epidemic of opioid use disorder given their roles in prescribing/dispensing prescription opioids and providing care for patients with pain and addiction. As a result, they are uniquely positioned for primary prevention. Unfortunately, their capacity to engage in primary prevention is hindered by the minimal training they receive on pain management, substance abuse and addiction, and safe and timely opioid-prescribing/dispensing practices [1, 102]. Rectifying these shortcomings, both in post-graduate and professional training, must be a priority. Medical, nursing, physician assistant, and pharmacy school curricula, residency training programs, and continuing education should be enhanced to equip health care providers with the knowledge and skills to address NMUPO and addiction in clinical settings. To bolster the clinical benefits of any content and procedural training, efforts should concurrently aim to strengthen dyadic patient and interprofessional communication skills concerning pain management, risks and benefits of prescription opioids, and addiction. The training modality could vary; the incorporation of multiple exposures and interactive techniques, for example, could be beneficial [40•, 41,42,43,44, 101].

Secondary Prevention

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs and Diversion Control

Secondary prevention involves the early detection of a disease to decrease its severity and consequences [96]. For opioid use disorder, it can involve identifying non-medical use and diversion as a means of averting progression to addiction and the sequelae of untreated addiction. A central tool for doing so is prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), which are state-level, electronic databases used to monitor controlled substances prescribed/dispensed to patients [103]. Often overseen by state Departments of Health or Boards of Pharmacy, PDMPs can be used to identify potential abuse or diversion of controlled substances, obtain data on the controlled substance history of a patient, and detect problematic prescribing/dispensing practices [103, 104]. Nearly all states have PDMPs actively gathering data from dispensing pharmacies and reporting it to authorized users [104]. Promising literature suggests that PDMP use could contribute to a number of desirable outcomes, such as reduced opioid diversion, use/misuse, and overdose deaths as well as improved prescribing/dispensing practices [48,49,50,51, 52•, 101]. The CDC further concludes that “PDMPs continue to be among the most promising state-level interventions to improve opioid prescribing, inform clinical practice, and protect patients at risk” [103].

Besides PDMPs, additional state-level diversion control strategies can support the secondary prevention of opioid use disorder, especially since states are largely responsible for regulating and enforcing practices concerning prescription drugs [105]. Specifically, state legislation and enforcement initiatives could decrease diversion and other adverse events stemming from NMUPO. The regulation of pain management clinics is a promising strategy from a legislative perspective. Such regulations can target inappropriate, high volume prescribing, a practice commonly associated with “pill mills,” thereby reducing a significant source of prescription opioids for diversion and non-medical use [105]. While pain management clinic regulations vary, they may impose constraints on clinic ownership, operation, and prescribing/dispensing practices, and allow for oversight/regulatory opportunities, among other actions [106]. Tactics and investigations implemented by law enforcement to decrease diversion can also align with secondary prevention. Florida’s response to increasing overdose deaths and pill mills offers evidence of the potential effect of concurrent state actions. In 2010–2012, the state implemented multiple initiatives directed at pill mills and unsound prescribing practices, including legislation and law enforcement operations [51, 53, 54]. Overall, they have been associated with promising effects, such as reductions in opioid diversion, prescribing and use, and overdose deaths [49, 51, 53, 54].

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment

A strategy that maps squarely onto the secondary prevention of addiction is screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT). It is a public health approach to substance use and abuse prevention and treatment that incorporates universal screening, detection of risky or hazardous substance use, early intervention, and referral to treatment for individuals identified with substance use disorder within a single, evidence-based model [59]. Advantages of SBIRT include its brevity, the potential to target multiple problematic behaviors, and the flexibility for multi-setting implementation (e.g., clinics and schools) [59]. Evidence supports the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SBIRT, particularly screening and brief intervention, for risky alcohol use [59, 60]. While the evidence base for its effectiveness in addressing risky drug use is comparatively smaller, and at times mixed, it is growing [59].

Tertiary Prevention

Abstinence-Based and Medication-Assisted Treatment

Tertiary prevention focuses on decreasing the complications of a disease through treatment and other support [96]. For the disease of addiction, facilitating access to and use of evidence-based treatment is a key element of tertiary prevention. Treatment options include medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and psychosocial approaches, such as residential treatment and 12-step models [2, 66]. MAT uses pharmacotherapy (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone) in combination with psychosocial interventions and support to treat opioid addiction [66, 67]. A large body of evidence indicates that it is a safe, effective, and cost-effective treatment for opioid addiction [67, 68••, 107]. It has been shown to improve treatment retention, minimize illicit opioid use, and is promising for gains in social functioning and reducing mortality, transmission of infectious diseases, and criminal activity [67, 68••, 108]. As for psychosocial interventions, evidence suggests that they can be beneficial in the treatment of substance use disorders when used alone and in conjunction with pharmacological treatment [66, 69, 70]. For example, a moderate level of evidence indicates that residential treatment can be effective for some patients, while aspects of membership in the 12-step fellowship of Narcotics Anonymous (NA) may have a role in long-term recovery [109, 110]. Treatment with methadone or buprenorphine, though, has been found to be more effective and less expensive than other forms of non-MAT behavioral health treatment [111]. Further, a longitudinal study of treatment for prescription opioid addiction suggested that participation in MAT was related to a higher likelihood of abstinence from illicit opioids [112].

Ultimately, there is no one treatment approach that is effective for all individuals with addiction [71]. Treatment approaches and settings should be selected, and tailored as necessary, to meet the needs of each individual [71]. Nevertheless, opioid addiction is a treatable disease, underscoring the importance of facilitating access to all forms of evidence-based treatment as a means of curbing potential complications from untreated opioid addiction.

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: Treatment of Mother, Infant, and Preventing Second Pregnancy

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) is another serious consequence of the disease of addiction. Tragically, infants are born physiologically dependent on opioids and go through withdrawal after separation from the mothers’ blood supply, resulting in a NAS diagnosis. A tertiary prevention approach to mitigating NAS as a complication of maternal addiction is two-fold. First, evidence-based treatment should be delivered to mothers and infants. For pregnant women with opioid addiction, MAT is the standard of care [113]. Clinical practice guidance is being evaluated on an urgent and ongoing basis to lessen infant suffering and to prevent long-term developmental consequences, many of which are unknown at this point. After delivery, pharmacological and non-pharmacological (e.g., breastfeeding) interventions have demonstrated promise in managing NAS [76, 77]. Second, the prevention of unintended pregnancies among mothers of infants diagnosed with NAS is important for reducing additional cases of NAS [114]. It has been estimated that nearly nine out of ten pregnancies among women abusing opioids are unintended, which highlights the value of prevention [115]. Specifically, voluntary reversible long-acting contraception (VRLAC) is a safe and highly effective method to prevent unintended pregnancy, thereby preventing NAS [78]. Its use should therefore be promoted.

Evidence-Based Drug Courts

Drug abuse, criminal activity, and involvement in the criminal justice system are often intertwined. Approximately half of incarcerated individuals (i.e., inmates) meet the diagnostic criteria for drug abuse or dependence, yet only a minority receive treatment [83, 116]. Substance use is also prevalent among detained juveniles, with almost half of detained youth estimated to have one or more substance use disorders according to one study [117]. There can be a cyclical relationship between crime and drug abuse, a potential factor contributing to the characterization of prisons and jails as the largest establishments to house individuals with mental illness [83, 116]. The interface of treatment with the criminal justice system holds significant potential for “breaking the cycle” and supporting individuals in leading full and productive lives [83, 118].

Drug courts are an effective strategy for integrating evidence-based addiction treatment into the criminal justice system. Typically operated by a multidisciplinary team, these specialized court programs target eligible criminal defendants and offenders, juvenile offenders, and parents with pending child welfare cases [119]. While drug courts can differ, a comprehensive drug court model may consist of screening and assessment, judicial interaction, monitoring and supervision, sanctions and incentives, and treatment and rehabilitation [119]. Evidence suggests that drug courts are cost-effective and can reduce recidivism and substance abuse among adults and potentially juveniles [83, 84••, 85, 86, 120].

Overdose Reversal With Naloxone

Overdose deaths involving prescription and illicit opioids have reached unprecedented levels. Naloxone, an opioid antagonist without abuse potential, can safely and effectively reverse opioid overdose and is the standard of care for possibly deadly respiratory depression from an opioid overdose [90, 121]. For decades, it has been used by emergency medical personnel, and now, it is increasingly being distributed to and administered by trained laypersons and health professionals through community-based overdose prevention programs [91, 121, 122]. Findings suggest that such programs can lead to opioid overdose reversals and potentially decrease opioid overdose death rates, which align with national, state, and local initiatives to improve access to naloxone [90,91,92]. Notably, multiple programs across the USA (e.g., Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City) have specifically targeted people who use drugs and their social networks [93,94,95, 123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132]. Growing evidence illustrates positive impacts from programs that aim to equip people who use drugs with the resources to prevent and respond to an opioid overdose. Studies on such programs have documented not only improvements in overdose knowledge and response skills but also successful overdose reversals involving peer-administered naloxone and few adverse consequences [93,94,95, 123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132]. In a study of a pilot overdose prevention and management program in San Francisco, for example, 24 people who inject drugs were trained in heroin overdose prevention, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and naloxone administration and provided a naloxone kit [93]. During a 6-month follow-up period, they reported successful resuscitations in 20 cases of heroin overdose, performing CPR in response to 16 cases (80%) and administering naloxone in response to 15 cases (75%) [93]. Moreover, according to a survey of organizations across the USA that distribute naloxone kits to laypersons, people who use drugs comprise the majority of laypersons who both receive naloxone kits and perform reported overdose reversals [122]. Despite its potential life-saving implications, some may perceive there to be a risk in the provision of a “safety net” of this type; that people will not see the risk for overdose death as a likely outcome, thereby setting the conditions for riskier behavior. Anecdotal accounts of multiple overdose reversals involving the same person have been reported in the media. Regardless, naloxone has saved thousands of lives and must be propagated as an evidence-based solution [122]. Some may also perceive broad dissemination of naloxone as evidence of failure of the public health system, but it is hopefully a temporary situation that will be remedied with system-wide implementation of promising and evidence-based strategies across the disease continuum of addiction.

Conclusion

NMUPO and illicit use of opioids are both inflicting a growing burden of opioid use disorder and other adverse outcomes on the nation. As illustrated by our conceptual model, a comprehensive response comprised of multiple strategies and grounded in the best available evidence is critical for mitigating the problem. Implemented in isolation, each strategy described herein will have minimal impact because it will only target a single point along the disease continuum of addiction. Single strategy approaches may also exacerbate the risk of propagating the problem by detracting from its overall complexity.

In short, there is a pressing public health need for a multifaceted response of sufficient scale and intensity to address opioid use disorder and its consequences on a population level. Responsive actions should be balanced with protecting access to prescription opioids for pain management as appropriate [1, 102]. It is thus imperative that strategies be implemented in a concurrent and coordinated manner to reduce the likelihood of unintended consequences and to maximize the impact of the resources invested in them. To make a response of this magnitude a reality, it will require clear communication and committed collaboration among diverse, multi-sector stakeholders. It will be important to align funding priorities and policies, both state and federal, in such a way as to foster the cross-cutting communication and collaboration that is needed. Finally, a response should be coupled with rigorous evaluation, with the aim of advancing the fields of substance abuse prevention and treatment and informing future public health initiatives [101].

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Office of National Drug Control Policy. Epidemic: responding to America's prescription drug abuse crisis. Executive Office of the President of the United States, Washington, DC. 2011. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/rx_abuse_plan.pdf.

Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, Kreiner P, Eadie JL, Clark TW, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559–74. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122957.

Manchikanti L, Helm S, Fellows B, Janata JW, Pampati V, Grider JS, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15:ES9–ES38.

Maxwell JC. The prescription drug epidemic in the United States: a perfect storm. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(3):264–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00291.x.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Prescription drug abuse (NIDA Research Report Series, NIH Publication Number 11–4881). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011.

Buchanich JM, Balmert LC, Burke DS. Exponential growth of the USA overdose epidemic. bioRxiv. 2017;134403. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/134403

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral health trends in the United States: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15–4927, NSDUH Series H-50). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Treatment episode data set (TEDS): 2003–2013. National admissions to substance abuse treatment services (BHSIS series S-75, HHS publication no. (SMA) 15–4934). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

Tolia VN, Patrick SW, Bennett MM, Murthy K, Sousa J, Smith PB, et al. Increasing incidence of the neonatal abstinence syndrome in U.S. neonatal ICUs. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(22):2118–26. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1500439.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers--United States, 1999--2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487–92.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid painkiller prescribing: where you live makes a difference. 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing/. Accessed 7 May 2016.

Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA, Hockenberry JM. Vital signs: variation among states in prescribing of opioid pain relievers and benzodiazepines--United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(26):563–8.

Van Zee A. The promotion and marketing of OxyContin: commercial triumph, public health tragedy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):221–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.131714.

Alexander G, Kruszewski SP, Webster DW. Rethinking opioid prescribing to protect patient safety and public health. JAMA. 2012;308(18):1865–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.14282.

Campbell J. APS 1995 presidential address. Pain Forum. 1996;5:85–8.

Morone NE, Weiner DK. Pain as the 5th vital sign: exposing the vital need for pain education. Clin Ther. 2013;35(11):1728–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.10.001.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. Fact sheet: a response to the epidemic of prescription drug abuse. Executive Office of the President, Washington, DC. 2011. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/Fact_Sheets/prescription_drug_abuse_fact_sheet_4-25-11.pdf.

Nargiso JE, Ballard EL, Skeer MR. A systematic review of risk and protective factors associated with nonmedical use of prescription drugs among youth in the United States: a social ecological perspective. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(1):5–20.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings (NSDUH series H-48, HHS publication no. (SMA) 14–4863). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Understanding stigma of mental and substance use disorders. In: Ending discrimination against people with mental and substance use disorders: the evidence for stigma change. Washington, DC: The National Academies of Press; 2016.

Rüsch N, Thornicroft G. Does stigma impair prevention of mental disorders? Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(4):249–51.

Barry CL, McGinty EE, Pescosolido BA, Goldman HH. Stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy: public views about drug addiction and mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(10):1269–72. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400140.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. DrugFacts: understanding drug use and addiction. 2016. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/understanding-drug-use-addiction. Accessed 7 May 2016.

Winstanley EL, Clark A, Feinberg J, Wilder CM. Barriers to implementation of opioid overdose prevention programs in Ohio. Subst Abus. 2016;37(1):42–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2015.1132294.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 43, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12–4214). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005.

Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):154–63. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1508490.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription drug overdose data. 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/overdose.html. Accessed 2 March 2016.

Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW, Patel MR, Galang RR, Shields J, et al. HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):229–39. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1515195.

Broz D. Large community outbreak of HIV-1 linked to injection drug use of oxymorphone - Indiana, 2015. Southern opioid epidemic: crafting an effective public health response symposium; Emory University, Atlanta, GA 2016.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Preventing drug use among children and adolescents: a research-based guide for parents, educators, and community leaders (NIH Publication No. 04–4212(A)). 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003.

National Research Council, Institute of Medicine. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009.

•• Sandler I, Wolchik SA, Cruden G, Mahrer NE, Ahn S, Brincks A, et al. Overview of meta-analyses of the prevention of mental health, substance use, and conduct problems. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:243–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185524. An overview of meta-analyses on the prevention of mental health, substance use, and conduct problems indicates prevention and promotion programs can produce significant impacts to prevent multiple problem outcomes, including depression, anxiety, antisocial behavior, and substance use.

Spoth R, Trudeau L, Shin C, Ralston E, Redmond C, Greenberg M, et al. Longitudinal effects of universal preventive intervention on prescription drug misuse: three RCTs with late adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):665–72. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301209.

Johnson EM, Porucznik CA, Anderson JW, Rolfs RT. State-level strategies for reducing prescription drug overdose deaths: Utah's prescription safety program. Pain Med. 2011;12(Suppl 2):S66–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01126.x.

Gray J, Hagemeier N, Brooks B, Alamian A. Prescription disposal practices: a 2-year ecological study of drug drop box donations in Appalachia. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e89–94. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2015.302689.

Spoth R, Trudeau L, Shin C, Redmond C. Long-term effects of universal preventive interventions on prescription drug misuse. Addiction. 2008;103(7):1160–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02160.x.

Champion KE, Newton NC, Barrett EL, Teesson M. A systematic review of school-based alcohol and other drug prevention programs facilitated by computers or the internet. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32(2):115–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00517.x.

Faggiano F, Minozzi S, Versino E, Buscemi D. Universal school-based prevention for illicit drug use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:Cd003020. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003020.pub3.

Sussman S, Arriaza B, Grigsby TJ. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug misuse prevention and cessation programming for alternative high school youth: a review. J Sch Health. 2014;84(11):748–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12200.

• Kamarudin G, Penm J, Chaar B, Moles R. Educational interventions to improve prescribing competency: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e003291. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003291. Educational interventions can improve prescribing competency. The WHO Guide to Good Prescribing may offer a promising model for designing prescribing programs.

Bluestone J, Johnson P, Fullerton J, Carr C, Alderman J, BonTempo J. Effective in-service training design and delivery: evidence from an integrative literature review. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:51. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-51.

Davis D, Galbraith R. Continuing medical education effect on practice performance: effectiveness of continuing medical education; American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based educational guidelines. Chest 2009;135(3 Suppl):42s–48s. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2517.

Bloom BS. Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(3):380–5.

Bordage G, Carlin B, Mazmanian PE. Continuing medical education effect on physician knowledge: effectiveness of continuing medical education; American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based educational guidelines. Chest 2009;135(3 Suppl):29s–36s. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2515.

Lyon AR, Stirman SW, Kerns SE, Bruns EJ. Developing the mental health workforce: review and application of training approaches from multiple disciplines. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2011;38(4):238–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0331-y.

Mazmanian PE, Davis DA, Galbraith R. Continuing medical education effect on clinical outcomes: effectiveness of continuing medical education; American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based educational guidelines. Chest 2009;135(3 Suppl):49s–55s. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2518.

O'Neil KM, Addrizzo-Harris DJ. Continuing medical education effect on physician knowledge application and psychomotor skills; effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 Suppl):37s–41s. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2516.

Bao Y, Pan Y, Taylor A, Radakrishnan S, Luo F, Pincus HA, et al. Prescription drug monitoring programs are associated with sustained reductions in opioid prescribing by physicians. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(6):1045–51. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1673.

Surratt HL, O'Grady C, Kurtz SP, Stivers Y, Cicero TJ, Dart RC, et al. Reductions in prescription opioid diversion following recent legislative interventions in Florida. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(3):314–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.3553.

Patrick SW, Fry CE, Jones TF, Buntin MB. Implementation of prescription drug monitoring programs associated with reductions in opioid-related death rates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1324–32. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1496.

Rutkow L, Chang HY, Daubresse M, Webster DW, Stuart EA, Alexander GC. Effect of Florida's prescription drug monitoring program and pill mill laws on opioid prescribing and use. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1642–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3931.

• Reifler LM, Droz D, Bailey JE, Schnoll SH, Fant R, Dart RC, et al. Do prescription monitoring programs impact state trends in opioid abuse/misuse? Pain Med. 2012;13(3):434–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01327.x. Findings provide preliminary evidence that prescription drug monitoring programs may reduce opioid abuse and misuse over time.

Johnson H, Paulozzi L, Porucznik C, Mack K, Herter B. Decline in drug overdose deaths after state policy changes - Florida, 2010-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(26):569–74.

Kennedy-Hendricks A, Richey M, McGinty EE, Stuart EA, Barry CL, Webster DW. Opioid overdose deaths and Florida's crackdown on pill mills. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):291–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2015.302953.

Lyapustina T, Rutkow L, Chang HY, Daubresse M, Ramji AF, Faul M, et al. Effect of a “pill mill” law on opioid prescribing and utilization: the case of Texas. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;159:190–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.025.

Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence at Brandeis University. Briefing on PDMP effectiveness. Prescription Drug Monitoring Prgram Center of Excellence at Brandeis University, Waltham, MA. 2013. http://www.pdmpexcellence.org/sites/all/pdfs/briefing_PDMP_effectiveness_april_2013.pdf.

Reisman RM, Shenoy PJ, Atherly AJ, Flowers CR. Prescription opioid usage and abuse relationships: an evaluation of state prescription drug monitoring program efficacy. Subst Abuse. 2009;3:41–51.

Worley J. Prescription drug monitoring programs, a response to doctor shopping: purpose, effectiveness, and directions for future research. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(5):319–28. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2011.654046.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Systems-level implementation of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (Technical Assistance Publication (TAP) Series 33, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4741). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013.

Angus C, Latimer N, Preston L, Li J, Purshouse R. What are the implications for policy makers? A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of screening and brief interventions for alcohol misuse in primary care. Front Pyschiatry. 2014;5:114. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00114.

Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor T, Souza-Formigoni ML, de Lacerda RB, Ling W, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for illicit drugs linked to the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) in clients recruited from primary health-care settings in four countries. Addiction. 2012;107(5):957–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03740.x.

Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, Stegbauer T, Stein JB, Clark HW. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and six months. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1–3):280–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003.

O'Donnell A, Anderson P, Newbury-Birch D, Schulte B, Schmidt C, Reimer J, et al. The impact of brief alcohol interventions in primary healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(1):66–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agt170.

Sterling S, Valkanoff T, Hinman A, Weisner C. Integrating substance use treatment into adolescent health care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(5):453–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0304-9.

Barbosa C, Cowell A, Bray J, Aldridge A. The cost-effectiveness of alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in emergency and outpatient medical settings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;53:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.01.003.

Dugosh K, Abraham A, Seymour B, McLoyd K, Chalk M, Festinger D. A systematic review on the use of psychosocial interventions in conjunction with medications for the treatment of opioid addiction. J Addict Med. 2016;10(2):93–103. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000193.

Thomas CP, Fullerton CA, Kim M, Montejano L, Lyman DR, Dougherty RH, et al. Medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):158–70. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300256.

•• Fullerton CA, Kim M, Thomas CP, Lyman DR, Montejano LB, Dougherty RH, et al. Medication-assisted treatment with methadone: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):146–57. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300235. In this review of meta-analyses, systematic reviews and individual studies, methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) had a positive impact on treatment retention and illicit opioid use, especially at doses over 60 mg. There is also evidence for improvements in drug-related HIV risk behaviors, mortality, and criminality.

Jhanjee S. Evidence based psychosocial interventions in substance use. Indian J Psychol Med. 2014;36(2):112–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.130960.

Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179–87. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of drug addiction treatment: a research-based guide (NIH Publication No. 12–4180). 3rd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012.

Hogue A, Henderson CE, Ozechowski TJ, Robbins MS. Evidence base on outpatient behavioral treatments for adolescent substance use: updates and recommendations 2007-2013. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43(5):695–720. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2014.915550.

Institute of Medicine. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, DC: The National Academies of Press; 2015.

Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:Cd002207. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4.

Tanner-Smith EE, Wilson SJ, Lipsey MW. The comparative effectiveness of outpatient treatment for adolescent substance abuse: a meta-analysis. J Subst Abus Treat. 2013;44(2):145–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.05.006.

McQueen K, Murphy-Oikonen J. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(25):2468–79. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1600879.

Bagley SM, Wachman EM, Holland E, Brogly SB. Review of the assessment and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2014;9(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1940-0640-9-19.

Blumenthal PD, Voedisch A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Strategies to prevent unintended pregnancy: increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(1):121–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmq026.

Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Buckel C, Madden T, Allsworth JE, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1998–2007. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1110855.

Brogly SB, Saia KA, Walley AY, Du HM, Sebastiani P. Prenatal buprenorphine versus methadone exposure and neonatal outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(7):673–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwu190.

Kraft WK, Stover MW, Davis JM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: pharmacologic strategies for the mother and infant. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40(3):203–12. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2015.12.007.

MacMullen NJ, Dulski LA, Blobaum P. Evidence-based interventions for neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatr Nurs. 2014;40(4):165–72. 203

Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: improving public health and safety. JAMA. 2009;301(2):183–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2008.976.

•• Carey SM, Mackin JR, Finigan MW. What works? The ten key components of drug court: research-based best practices. Drug Court Rev. 2012;8(1):6–42. Drug courts can effectively reduce recidivism and increase cost savings among diverse populations. Based on the 69 programs evaluated, the average reduction in recidivism was 32% and the average increase in cost savings was 27%.

Brown RT. Systematic review of the impact of adult drug-treatment courts. Transl Res. 2010;155(6):263–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2010.03.001.

Marlowe DB. Research update on adult drug courts. Need to know. National Association of Drug Court Professionals, Alexandria, VA. 2010. https://www.ndci.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Research-Update-on-Adult-Drug-Courts-NADCP_1.pdf.

Marlowe DB. Research update on juvenile drug treatment courts. Need to Know. National Association of Drug Court Professionals, Alexandria, VA. 2010. https://www.ndci.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Research-Update-on-Juvenile-Drug-Treatment-Courts-NADCP_1.pdf.

Marlowe DB, Carey SM. Research update on family drug courts. Need to Know. National Association of Drug Court Professionals, Alexandria, VA. 2012. https://www.ndci.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Reseach-Update-on-Family-Drug-Courts-NADCP.pdf.

Stein DM, Deberard S, Homan K. Predicting success and failure in juvenile drug treatment court: a meta-analytic review. J Subst Abus Treat. 2013;44(2):159–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.07.002.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone - United States. 2010 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(6):101–5.

Clark AK, Wilder CM, Winstanley EL. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J Addict Med. 2014;8(3):153–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000034.

Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, Quinn E, Doe-Simkins M, Sorensen-Alawad A, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f174.

Seal KH, Thawley R, Gee L, Bamberger J, Kral AH, Ciccarone D, et al. Naloxone distribution and cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for injection drug users to prevent heroin overdose death: a pilot intervention study. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2):303–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti053.

Piper TM, Stancliff S, Rudenstine S, Sherman S, Nandi V, Clear A, et al. Evaluation of a naloxone distribution and administration program in New York City. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43(7):858–70.

Bennett AS, Bell A, Tomedi L, Hulsey EG, Kral AH. Characteristics of an overdose prevention, response, and naloxone distribution program in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. J Urban Health. 2011;88(6):1020–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9600-7.

Gordis L. Epidemiology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

Nation M, Crusto C, Wandersman A, Kumpfer KL, Seybolt D, Morrissey-Kane E, et al. What works in prevention. Principles of effective prevention programs. Am Psychol. 2003;58(6–7):449–56.

National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Adolescent substance use. America's #1 public health problem. New York, NY: National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 2011.

Miller T, Hendrie D. Substance abuse prevention dollars and cents: a cost-benefit analysis (DHHS Pub. No. (SMA) 07–4298). Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2008.

Butterfoss FD, Cohen L. Prevention works. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10(2 Suppl):81s–5s. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839909336104.

Haegerich TM, Paulozzi LJ, Manns BJ, Jones CM. What we know, and don't know, about the impact of state policy and systems-level interventions on prescription drug overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:34–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.001.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Addressing prescription drug abuse in the United States: current activities and future opportunities. Behavioral Health Coordinating Committee, Prescription Drug Abuse Subcommittee, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/hhs_prescription_drug_abuse_report_09.2013.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs). 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdmp/. Accessed 7 May 2016.

Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Training and Technical Assistance Center. Prescription drug monitoring frequently asked questions (FAQ). http://www.pdmpassist.org/content/prescription-drug-monitoring-frequently-asked-questions-faq. Accessed 7 May 2016.

Public Health Law Program, Office for State, Tribal, Local and Territorial Support, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Menu of pain management clinic regulation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. 2012. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/docs/menu-pmcr.pdf.

National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. Part 2: state regulation of pain clinics and legislative trends relative to regulating pain clinics. Prescription drug abuse, addiction and diversion: overview of state legislative and policy initiatives; a three part series. National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws, Charlottesville, VA. 2014. http://www.namsdl.org/library/8867EBE1-19B9-E1C5-316C1FDCB35571A5/.

Connock M, Juarez-Garcia A, Jowett S, Frew E, Liu Z, Taylor RJ et al. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2007;11(9):1–171, iii-iv.

Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies — tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1402780.

Reif S, George P, Braude L, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, et al. Residential treatment for individuals with substance use disorders: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(3):301–12. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300242.

Galanter M, Dermatis H, Post S, Sampson C. Spirituality-based recovery from drug addiction in the twelve-step fellowship of narcotics anonymous. J Addict Med. 2013;7(3):189–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e31828a0265.

Clark RE, Baxter JD, Aweh G, O'Connell E, Fisher WH, Barton BA. Risk factors for relapse and higher costs among medicaid members with opioid dependence or abuse: opioid agonists, comorbidities, and treatment history. J Subst Abus Treat. 2015;57:75–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.05.001.

Weiss RD, Potter JS, Griffin ML, Provost SE, Fitzmaurice GM, McDermott KA, et al. Long-term outcomes from the national drug abuse treatment clinical trials network prescription opioid addiction treatment study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;150:112–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.030.

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524: opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119(5):1070–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318256496e.

Warren MD, Miller AM, Traylor J, Bauer A, Patrick SW. Implementation of a statewide surveillance system for neonatal abstinence syndrome - Tennessee. 2013 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(5):125–8.

Heil SH, Jones HE, Arria A, Kaltenbach K, Coyle M, Fischer G, et al. Unintended pregnancy in opioid-abusing women. J Subst Abus Treat. 2011;40(2):199–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2010.08.011.

Dumont DM, Brockmann B, Dickman S, Alexander N, Rich JD. Public health and the epidemic of incarceration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:325–39. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124614.

McClelland GM, Elkington KS, Teplin LA, Abram KM. Multiple substance use disorders in juvenile detainees. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(10):1215–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000134489.58054.9c.

National Institute of Drug Abuse. Principles of drug abuse treatment for criminal justice populations: a research-based guide (NIH Publication No. 11–5316). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

National Institute of Justice. Drug courts. 2015. http://www.nij.gov/topics/courts/drug-courts/pages/welcome.aspx. Accessed 8 May 2016.

Sheidow AJ, Jayawardhana J, Bradford WD, Henggeler SW, Shapiro SB. Money matters: cost effectiveness of juvenile drug court with and without evidence-based treatments. J Child Adolesc Subst. 2012;21(1):69–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828x.2012.636701.

Kim D, Irwin KS, Khoshnood K. Expanded access to naloxone: options for critical response to the epidemic of opioid overdose mortality. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):402–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2008.136937.

Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons - United States. 2014 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(23):631–5.

Fairbairn N, Coffin PO, Walley AY. Naloxone for heroin, prescription opioid, and illicitly made fentanyl overdoses: challenges and innovations responding to a dynamic epidemic. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:172–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.005.

Bazazi AR, Zaller ND, Fu JJ, Rich JD. Preventing opiate overdose deaths: examining objections to take-home naloxone. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1108–13. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2010.0935.

Maxwell S, Bigg D, Stanczykiewicz K, Carlberg-Racich S. Prescribing naloxone to actively injecting heroin users: a program to reduce heroin overdose deaths. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(3):89–96.

Galea S, Worthington N, Piper TM, Nandi VV, Curtis M, Rosenthal DM. Provision of naloxone to injection drug users as an overdose prevention strategy: early evidence from a pilot study in New York City. Addict Behav. 2006;31(5):907–12.

Green TC, Heimer R, Grau LE. Distinguishing signs of opioid overdose and indication for naloxone: an evaluation of six overdose training and naloxone distribution programs in the United States. Addiction. 2008;103(6):979–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02182.x.

Tobin KE, Sherman SG, Beilenson P, Welsh C, Latkin CA. Evaluation of the staying alive programme: training injection drug users to properly administer naloxone and save lives. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(2):131–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.03.002.

Enteen L, Bauer J, McLean R, Wheeler E, Huriaux E, Kral AH, et al. Overdose prevention and naloxone prescription for opioid users in San Francisco. J Urban Health. 2010;87(6):931–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-010-9495-8.

Wagner KD, Valente TW, Casanova M, Partovi SM, Mendenhall BM, Hundley JH, et al. Evaluation of an overdose prevention and response training programme for injection drug users in the skid row area of Los Angeles. California Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(3):186–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.01.003.

Lankenau SE, Wagner KD, Silva K, Kecojevic A, Iverson E, McNeely M, et al. Injection drug users trained by overdose prevention programs: responses to witnessed overdoses. J Community Health. 2013;38(1):133–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-012-9591-7.

Behar E, Santos G-M, Wheeler E, Rowe C, Coffin PO. Brief overdose education is sufficient for naloxone distribution to opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:209–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.009.

Funding

The work was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award R24DA036409. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on The Global Epidemic

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mathis, S.M., Hagemeier, N., Hagaman, A. et al. A Dissemination and Implementation Science Approach to the Epidemic of Opioid Use Disorder in the United States. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 15, 359–370 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-018-0409-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-018-0409-9