Abstract

Purpose of review

Multiple reviews have examined eHealth/mHealth interventions to address treatment adherence, including those focusing on youth living with HIV (YLWH). This review synthesizes results of prior reviews and recent studies (last 5 years) to provide a path forward for future research, acknowledging both lessons learned and gaps to be addressed.

Recent findings

Recent studies provide further evidence for the feasibility and acceptability of technology-based HIV interventions. Formative research of more comprehensive smartphone applications and pilot studies of computer-delivered interventions provide additional guidance on YLWH’s preferences for intervention components and show promising preliminary efficacy for impacting treatment adherence.

Summary

Expanding access to technology among YLWH, in the United States (US) and globally, supports the continued focus on eHealth/mHealth interventions as a means to reduce disparities in clinical outcomes. Future research should lend greater focus to implementation and scale-up of interventions through the use of adaptive treatment strategies that include costing analyses, measuring and maximizing engagement, fostering information sharing between researchers, and building upon sustainable platforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite substantial declines in HIV transmission and increases in lifespan achieved over the past decade for those living with HIV, the full benefits of currently available tools and interventions are still not completely realized by youth living with HIV (YLWH). In the US, only 48.1% of diagnosed HIV-positive youth (aged 13–24 years) achieve viral suppression (VS; < 200 copies/mL at the most recent viral load test) [1], and it has been estimated that less than 6% of HIV-infected youth in the US remain virally suppressed [2]. A recent systematic review examining viral suppression among YLWH globally highlighted the scarcity of data on the topic, noting that among the six low- to moderate-quality studies identified, suppression rates were highly variable (ranging from 27 to 89% at 12-months post-ART initiation) [3]. Another recent systematic review and meta-analysis of the HIV care continuum among youth in South Africa estimated that only 10% of HIV-infected youth (15–24 years) were virally suppressed [4].

Reviews of antiretroviral (ART) adherence among YLWH (12–24 years) provide evidence of poor adherence rates. A 2014 meta-analysis of adherence for YLWH found overall low self-reported adherence of 62.3% [5•]. Barriers to adherence and VS among youth include forgetting or not being motivated to take medications [6], low adherence self-efficacy [7], psychological distress (depression, anxiety) [8,9,10], substance use [9, 10], structural barriers (e.g., transportation, insurance) [11, 12], low social support [13, 14], and HIV-related stigma [9, 14, 15]. The developmental changes that occur as youth transition from adolescence to young adulthood can create or exacerbate these adherence barriers [16, 17].

The potential utility of technology-based interventions to increase ART adherence and improve viral suppression among HIV-positive individuals was recognized in the early 2000s as global access to computers, the Internet, and mobile devices began to rapidly rise [18]. Since that time, many different types of electronic health (eHealth) and mobile health (mHealth) interventions have been developed to address ART adherence among YLWH, including those delivered using SMS/texting, social media, and smartphone apps [19•, 20]. While conclusive evidence supporting the efficacy and effectiveness of many of these innovative approaches is still lacking, the feasibility and acceptability of technology-based interventions for YLWH have been well established [20, 21, 22••].

Both in the US and globally, youths’ access to technology continues to grow. In the US, nearly all youth have access to the Internet and a cell phone [23]. In low- and middle-income countries, youths’ access to the Internet and cell phones continues to rise rapidly, though there are variations by country [24, 25]. Smartphone ownership is climbing in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), but the digital divide remains. While smartphone ownership in the US among those 18–29 years was 92% in 2016 [26], the median smartphone adoption rate in LMICs rose to 37% in 2015, up from 21% in 2013, according to a Pew Research Center survey of 21 LMICs conducted in 2015 [24]. Across nearly all countries, younger people (ages 18–34 years) are more likely than older individuals (35+ year) to own a smartphone [24]. In the US, the majority (88%) of teens (13–17 years old) own or have access to cell phones or smartphones and 90% of those teens with phones exchange texts. A typical teen in the US sends and receives 30 texts per day [23]. Given that access to technology among youth continues to grow and the feasibility and acceptability of technology-based adherence interventions for HIV-positive youth have been established, the rationale for delivering adherence interventions through these mechanisms remains strong. Although additional data is needed to determine efficacy and effectiveness of many types of eHealth and mHealth interventions for HIV-positive youth, many lessons have been learned that have the potential to improve intervention quality and move the field forward. In this review, we synthesize selected recent reviews [19•, 21, 22••, 27, 28, 29•, 30], and notable research conducted within the past 5 years focusing on treatment adherence interventions for HIV-positive youth. We aimed to provide a path forward that acknowledges both lessons learned and gaps still to be addressed.

Methods

We searched PubMed for English language publications, published between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2017, which included ≥ 1 term in Title/Abstract field from each group listed below:

-

Group 1: HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, AIDS

-

Group 2: antiretroviral, ART, therapy, medication, adherence, compliance, nonadheren*, retention, linkage, engagement, viral suppression, suppression

-

Group 3: technology, technology-based, SMS, text messag*, texting, online, internet, web, Web 2.0, social media, social network*, app*, application*, smartphone*, cell phone*, cellular phone*, mobile phone*, eHealth, mHealth, mobile health, digital, digital health, video conference*, videoconference*, Twitter, Grindr, Jack’d, Facebook, computerize*, computer-based, virtual reality, VR

-

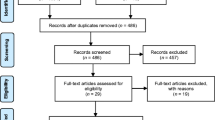

Group 4: youth, young adult*, adolescen*, teen*, young

Publications were excluded that did not include the following: an intervention description, an eHealth/mHealth intervention component, a treatment adherence behavioral (e.g., self-reported medication taking, attendance at clinic visits) or bio-medical (e.g., viral load, viral suppression, and drug levels) outcome, and a focus on adolescent/young adult populations (ages 10–24). Formative studies were included if they described a proposed intervention and potential outcomes. Studies were excluded if they only used the calling features of mobile phones (e.g., voice calls). Three authors reviewed citations and full texts were pulled for all citations noted as relevant by at least one reviewer. Of the 143 articles extracted, 16 articles, including 7 describing formative work for intervention development, 6 reporting on pilot or randomized controlled trial (RCT) results, and 3 published study protocols for planned/ongoing interventions met inclusion criteria and were deemed most significant to current work in the field (Table 1). In addition, to ensure our discussion included a historical perspective, review articles (including systematic reviews and meta-analyses) published in the last 5 years (January 1, 2013 to January 1, 2018) that included relevant results were also extracted and reviewed.

We focus on adolescents and young adults, ages 10–24 years, in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) and other United Nations (UN) organizations, who define adolescents as those people between 10 and 19 years of age, youth as 15–24 years old, and refer to the combined group (10–24 year olds) as “young people” [50].

What Do We Know?

Unpacking the Results of SMS Interventions

There is evidence for overall acceptability and feasibility as well as modest efficacy of two-way SMS interventions at improving both adherence and retention in care. Multiple studies, including meta-analyses, integrative and systematic reviews [22••, 28, 29•], provide confirmation of moderate short-term effect; however, sustained effects have been less robust, particularly among youth. For example, in a recent pilot RCT evaluating the initial efficacy of personalized text message reminders to promote adherence among adolescents and young adults in Chicago (16–29 years old), the difference in mean adherence between intervention and control participants was significant during the 3-month follow-up, but this effect attenuated and was not significant at 6 months [40]. The overall acceptability of the intervention was high, with 95% of participants at 6 months reporting overall satisfaction with the intervention and 81% reporting wanting to continue receiving the text messages after the conclusion of the trial. Another study examining the feasibility of interactive daily text messages to improve adherence with youth reporting adherence difficulties (ages 14–29 years) demonstrated the feasibility of this approach in terms of participant responsiveness (participants responded to successfully sent messages 61.4% of the time over the 24-week study period) [38].

It is notable that an RCT examining the efficacy of SMS reminder messages conducted with younger youth in Kampala, Uganda (mean age = 18.5 years), did not find support for the effectiveness of SMS reminder messages on ART and cotrimoxazole prophylaxis adherence compared to the usual care control group at 12 months [41]. The trial examined the effectiveness of both one-way and two-way (i.e., with a response option) SMS reminder messages and noted low levels of user engagement in the group with the option to respond; across the 48-week study period, the response rate in the two-way SMS group was only 28.5%. Of note, messages in this study lacked personalization/tailoring of timing and content of messages. Given that youth often communicate through animated memes, Graphics Interchange Formats (GIFs), and videos, it may be that text-based interventions, particularly those that are not personalized and/or tailored to the participants, may not adequately capture the attention of the recipients. Formative data suggests that boredom with prolonged and/or repetitive messaging may be a relevant challenge with this population [35].

Given the collective evidence suggesting modest impact, high acceptability, and ubiquity of cell phones with texting capabilities [35], consideration should be given to shifting from testing text-based SMS interventions in RCTs to focusing on implementation studies that combine and integrate SMS with either ongoing clinical activities or as part of more comprehensive adherence strategies. Two trials underway will provide evidence for the effectiveness of this approach with youth. A cluster-randomized controlled trial with HIV-positive adolescents (ages 13–19 years) in Zimbabwe [48] will examine the effectiveness of a clinic-level intervention that includes support provided by a designated community adolescent treatment supporter (CATS). The CATS organizes in-person monthly support groups in addition to writing and sending weekly, individualized SMS messages that include motivational reminders as well as information about clinic/support group attendance. Adolescents in the intervention who are in need of enhanced support will receive bi-weekly home visits in addition to weekly phone calls and daily SMS messages. Another study aimed at improving linkage to HIV care and retention among diverse young HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM) in the US [49] will evaluate an intervention in which a Health Educator uses various social media platforms (e.g., Facebook messenger, text messaging, and app-based instant messages), based on the participants’ preferences, to communicate with participants using theoretically informed messages that are specifically tailored to each participant. The Health Educator will also manage an optional secret Facebook group and have some face-to-face interactions with the participants.

Emerging Data on YLWH Preferences for Comprehensive eHealth/mHealth Interventions

Multiple formative studies conducted recently have identified comparable preferences for intervention components across multiple settings (both in the US and globally) and populations of HIV-positive youth [31,32,33, 35, 37]. Features mentioned consistently include the following: facilitating connections to providers and other YLWH, including reminders for HIV-related activities, and providing comprehensive and accurate information regarding HIV as well as general health and wellness.

Preferences for connecting with providers include the ability to directly message clinics and providers [32, 37], engage in real-time to receive individualized counseling support [31], as well as allow providers to have access to adherence data that users record in an app to trigger real-time adherence support [37]. Providing contact between clinics/providers and youth in-between scheduled visits could overcome structural barriers such as transportation and scheduling difficulties and allow youth to be more candid in articulating questions and concerns in a less-intimidating, more comfortable format.

Youth also expressed a desire to have access to other HIV-positive youth, in hopes that these relationships would provide support and allow reflection on their own adherence challenges and subsequently decrease feelings of social isolation [31,32,33, 37]. However, it is not clear what is the best way to create socially supportive networks in eHealth interventions, either through the development of “new” social media platforms or through integration into established social media (e.g., Facebook) [32]. One recent study, for example, reported on the successful integration of a private Facebook group established for HIV-positive young adults (ages 16–27 years) attending an urban HIV/AIDS care and treatment center in the US [51]. Content analysis of messages posted to the group showed that emotional social support was sought and provided frequently through this platform. There is a clear tension, however, between youth wanting to connect but also having concerns regarding inadvertent disclosures of same-sex sexual behaviors or HIV serostatus. In the private Facebook group, for example, several individuals who attended face-to-face meetings at the treatment center refused to join the online group because of privacy concerns and fears of their HIV status being revealed to their entire social network [51]. Suggestions for protection that were mentioned in other recent formative studies included the following: ensuring anonymity, secure (password protected) logins, pseudonyms/avatars [31,32,33, 37].

Youth consistently stressed the importance of their life beyond HIV and daily “pill-taking.” Interventions that take a more holistic approach to issues of relevance to YLWH through the provision of credible, up-to-date information on HIV as well as general health and wellness [31,32,33, 35, 37] may be more relevant and foster engagement. Similarly, incorporation of reminders into these interventions should not only focus on ART taking behavior reminders but also reminders about clinic appointments [31, 33, 35, 37].

Evidence for Non-SMS eHealth/mHealth Interventions Among YLWH Is Scant but Emerging

Recently conducted research also provides preliminary evidence for the feasibility and acceptability of computer-delivered interventions for youth, though these studies have all been conducted in the US. For example, a pilot RCT evaluating the preliminary efficacy of a two-session computer-based motivational interviewing intervention [45] showed promise among HIV-positive youth initiating ART (ages 16–24 years) recruited from eight US cities. Intervention participants reported high levels of satisfaction with the intervention and effect sizes, while not powered for significance testing, suggested that intervention participants had a greater drop in viral load from baseline to 6-month follow-up when compared to participants in attention-matched nutrition and physical activity control condition. Another recent pilot study that assessed the feasibility and acceptability of a telehealth (i.e., remote video-conferencing) medication counseling intervention with HIV-positive Black youth in the San Francisco Bay Area (18–29 years) [36] found that nearly all participants felt that the telehealth approach was private, and in some cases even more private than care they received at a clinic. Participants in this study reported feeling more comfortable disclosing their problems to the health care provider using the telehealth technology than in-person.

What Do We Need to Do Better?

Retention in eHealth/mHealth Interventions Is Critical but Understudied and Poorly Addressed

Understanding, measuring, and subsequently addressing engagement within mHealth adherence interventions are areas that requires greater attention [52, 53]. We propose three areas that can serve to focus future research, which include the following: (1) intervention usage (e.g., paradata), (2) youth-focused engagement strategies, and (3) adaptive intervention designs. Paradata (i.e., intervention usage metrics) have been associated with differential treatment outcomes in mHealth interventions [54,55,56,57]; yet, they remain under-examined and underreported in technology-based HIV prevention and care interventions [58, 59••]. The systematic collection and analysis of paradata will not only strengthen the evidence base for mHealth adherence interventions (do they work?) and improve our understanding of how interventions work (what components led to behavior change?), but also inform reach and scale-up efforts (for whom do they work, under what conditions, and what is the optimal dose?).

A recent review of mHealth interventions to support medication adherence among HIV-positive MSM concluded that an important area for future growth includes overcoming engagement challenges, by considering incorporating gamification and dynamic tailoring based on frequent assessments [19•]. In the formative work, described in Table 1, YLWH provided examples of strategies they felt would increase their engagement including examples of gamification (points, rewards, contests, and game-based elements [31,32,33]), provision of incentives [32], and enabling social connections [32, 33]. One recent study that examined the feasibility of using voice and internet daily diaries to collect data on daily ART adherence among young HIV-positive MSM in three US cities (ages 16–24 years) [60], implemented a unique, tiered incentive structure based on principles of loss aversion and variable reinforcement; participants started with $25 in a compensation account, with increasing amounts (ranging from $2 to $6) added for diaries completed and $1 removed for diaries missed. Participants were also entered into a lottery for every diary completed. Participants completed 72.4% of the daily dairies over the 60-day study window and remarked on the motivating nature of the compensation/incentive structure during debriefing interviews.

Moving Beyond Traditional Trial Designs

Advances in mobile technology offer novel opportunities for moving beyond the RCT and delivering adaptive interventions that operationalize the personalization of real-time selection and delivery of intervention strategies based on real-time data [61]. In adaptive interventions, the type or dose of the intervention is adjusted based on participant characteristics or response. Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAI) and sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (SMART) have numerous advantages over traditional trial designs and are an efficient and rigorous way to maximize clinical utility and real-world applicability [62,63,64]. While no completed studies in this review utilized these proposed methodologies, one published study protocol described a forthcoming trial in which newly diagnosed adolescent girls will be enrolled in a SMART pilot trial to determine the most effective way to support initial linkage to care after a positive diagnosis [47]. They will be randomized to standard referral (counseling and a referral note) or standard referral plus a single SMS text message; those not linked to care within 2 weeks will be re-randomized to receive an additional SMS text message or a one-time financial incentive.

Ensuring Interventions Are Inclusive of YLWH from All Age Strata

There is a striking lack of research focusing specifically on HIV-positive adolescents between the ages of 10–19 years. While our review identified several studies conducted with HIV-positive youth, including formative/qualitative studies and pilot studies that span adolescence and young adulthood, the mean age in most of these studies is 20 and up. This is important as we consider that there are likely differences in mHealth/eHealth intervention feasibility and acceptability between youth at the younger age spectrum.

First, there may be important differences in the characteristics of younger YLWH. While there are developmental changes (e.g., neurodevelopmental changes [65]) that continue to occur into the early twenties, adolescents between the ages of 10–19 years are undergoing many important physical, biological, emotional, and psychological changes during this phase of their development [66]. There may also be differences in the social environment of younger vs. older youth, with the former spending more time with their families and the latter spending more time with friends, peers, and subsequently engaging in more intimate individual relationships [66, 67]. eHealth interventions that aim to reduce social isolation by fostering connections to others may need to address these evolving social contexts when engaging younger participants.

Perinatally infected adolescents may also face unique challenges as they assume greater levels of independence and autonomy for their healthcare-related activities, particularly when transitioning out of pediatric care, which is typically managed by parents and guardians [68]. In fact, progression through adolescence is an established risk factor for poor adherence among perinatally infected youth [69, 70]. This is especially important to consider when developing eHealth interventions for youth in sub-Saharan Africa since millions of children currently living with HIV will be growing into adolescence in the coming years [71]. Further, there may be differences between perinatally and behaviorally infected adolescents in terms of stigma dynamics surrounding their diagnosis and to whom they have disclosed; these issues must be understood and carefully addressed in mHealth/eHealth intervention designed for them.

Additionally, in many cultures, the norms with regard to autonomy and parental/caregiver oversight for adolescents are very different than those relevant for young adults in their early twenties [72]. Practically speaking, this may result in important differences in terms of phone-use restrictions, sharing, and ownership among younger youth when compared to young adults, as well as in recruitment as research participants. For example, a Pew Research Center survey conducted with parents of US teens, ages 13–17 years, found that 55% of parents limit the amount of time or times of day that their teen can go online and 65% of parents reported having punished their teen by taking away their phone or access to the Internet [73]. In the Rana study among YLWH (14–24 years) on ART in two clinics in Kampala, Uganda, nearly half of sample participants (41%) reported sharing phones with others. Youth were most likely to share phones with family members such as mothers, grandmothers, and older siblings [35]. Phone sharing can be a large issue if youth have not disclosed their status. A recently funded suite of three technology-based interventions [74,75,76] aimed at cognitive precursors to HIV risk as well as HIV risk behaviors, among 13–18 year-old diverse, same-sex attracted youth, may help to inform recruitment and engagement of younger adolescents.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Moving from Development to Dissemination

While we have come a long way in the development and evaluation of mHealth interventions for YLWH, there are still significant gaps in moving the pilot work completed to date into large-scale, intervention implementation, and dissemination. Planning for future scale-up and long-term sustainability should be taken into account during initial planning and technology development. This includes ensuring that economic evaluations that assess cost/cost-effectiveness are prioritized as key intervention outcomes of technology-based interventions. In a recent review by Badawy et al. focused on the economic evaluation of text-messaging and smartphone-based interventions aimed at improving medication adherence in adolescents with chronic health conditions (CHCs) [30], only four articles (text messaging [n = 3], electronic directly observed therapy [n = 1]) described interventions with possible future cost-savings. However, none of the interventions included any formal economic evaluations leaving little evidence to support the cost-effectiveness of text-messaging and smartphone-based interventions in improving medication adherence in adolescents with CHCs. The recently funded UNC/Emory Center for Innovative Technology (iTech) Across the Prevention and Care Continuum (www.itechnetwork.org) [76] is developing standardized cost collection tools and analytic strategies that will be utilized across iTech’s current research portfolio of 10 technology-based (e.g., apps, mobile websites, videoconferencing) interventions for youth (aged 15–24 years).

Toward a More Collaborative Future

Finally, it is likely time to stop “recreating the wheel” both in terms of the content that is included within eHealth interventions (e.g., text message reminders, HIV, and general health articles, FAQs) as well as the platforms that the interventions are being built upon. For example, in review of 10 computer-based interventions focused on adherence, there was significant overlap in content related to adherence knowledge and strategies, ART side effects, and patient-provider communication [21]. Consideration should be given to the creation of a content repository for researchers that could be updated and adapted for the unique needs, developmental stage, and cultural features of the population of interest (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, gender). Additionally, building interventions for YLWH on existing platforms or using open source options would allow for more rapid development and result in substantial cost savings. Within iTech, many platforms initially developed for adults or other populations are being adapted for youth, rather than starting from scratch [77, 78].

Conclusions

Evidence of feasibility and acceptability of technology-based HIV interventions and promising preliminary outcomes of tested interventions support the continued focus on these types of interventions as a means to reduce disparities in adherence and VS among YLWH. Further, expanding access to and use of technology among youth suggests the importance of these interventions both in the US and globally. While technology allows for tailoring to the unique adherence patterns of HIV-positive youth, it is critical to include users in the design to ensure interventions appropriately address context and psychosocial factors impacting adherence. Examining evidence to date, lessons learned, and gaps in knowledge will help to identify a path forward–a path toward interventions that are best suited to addressing the adherence needs of todays youth.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data- US and 6 dependent areas 2015. 2017.

Zanoni BC, Mayer KH. The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28(3):128–35. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2013.0345.

Ferrand RA, Briggs D, Ferguson J, Penazzato M, Armstrong A, MacPherson P, et al. Viral suppression in adolescents on antiretroviral treatment: review of the literature and critical appraisal of methodological challenges. Tropical Med Int Health. 2016;21(3):325–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12656.

Zanoni BC, Archary M, Buchan S, Katz IT, Haberer JE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the adolescent HIV continuum of care in South Africa: the cresting wave. BMJ Global Health. 2016;1(3):e000004. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000004.

• Kim SH, Gerver SM, Fidler S, Ward H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in adolescents living with HIV: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England) 2014;28(13):1945–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/qad.0000000000000316. This article includes a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies reporting adherence to ART for adolescents and young adults (ages 12-24 years) living with HIV. The authors identified 50 eligible articles reporting data from 53 countries.

MacDonell K, Naar-King S, Huszti H, Belzer M. Barriers to medication adherence in behaviorally and perinatally infected youth living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):86–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0364-1.

Houston E, Fominaya AW. Antiretroviral therapy adherence in a sample of men with low socioeconomic status: the role of task-specific treatment self-efficacy. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(8):896–905. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2014.986137.

Shacham E, Estlund AL, Tanner AE, Presti R. Challenges to HIV management among youth engaged in HIV care. AIDS Care. 2017;29(2):189–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1204422.

Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Garofalo R, Muldoon AL, Jaffe K, Bouris A, et al. An index of multiple psychosocial, Syndemic conditions is associated with antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2016;30(4):185–92. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2015.0328.

Gross IM, Hosek S, Richards MH, Fernandez MI. Predictors and profiles of antiretroviral therapy adherence among African American adolescents and young adult males living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2016;30(7):324–38. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2015.0351.

Rudy BJ, Murphy DA, Harris DR, Muenz L, Ellen J. Patient-related risks for nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected youth in the United States: a study of prevalence and interactions. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23(3):185–94. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2008.0162.

Rudy BJ, Murphy DA, Harris DR, Muenz L, Ellen J. Prevalence and interactions of patient-related risks for nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among perinatally infected youth in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24(2):97–104. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2009.0198.

Macdonell KE, Naar-King S, Murphy DA, Parsons JT, Harper GW. Predictors of medication adherence in high risk youth of color living with HIV. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(6):593–601. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp080.

Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Hoffman D, Steers WN. Predictors of antiretroviral adherence. AIDS Care. 2004;16(4):471–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120410001683402.

Bogart LM, Landrine H, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ, Klein DJ. Perceived discrimination and physical health among HIV-positive black and Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1431–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0397-5.

Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: the winding road from late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004.

DeLaMora P, Aledort N, Stavola J. Caring for adolescents with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2006;3(2):74–8.

Ybarra ML, Bull SS. Current trends in internet- and cell phone-based HIV prevention and intervention programs. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(4):201–7.

• Muessig KE, LeGrand S, Horvath KJ, Bauermeister JA, Hightow-Weidman LB. Recent mobile health interventions to support medication adherence among HIV-positive MSM. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12(5):432–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0000000000000401. This study describes recent mobile health (mHealth) interventions (January 2016–13 May 2017) supporting antiretroviral therapy (ART) medication adherence among HIV-positive MSM. Conclusions from seven publications [text messaging (4), smartphone apps (2), social media (1)] were that mHealth interventions to support ART adherence among MSM show acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary efficacy.

Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Bauermeister J, Zhang C, LeGrand S. Youth, technology, and HIV: recent advances and future directions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(4):500–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-015-0280-x.

Claborn KR, Fernandez A, Wray T, Ramsey S. Computer-based HIV adherence promotion interventions: a systematic review: translation behavioral medicine. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5(3):294–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-015-0317-0.

•• Navarra AD, Gwadz MV, Whittemore R, Bakken SR, Cleland CM, Burleson W, et al. Health technology-enabled interventions for adherence support and retention in care among US HIV-infected adolescents and young adults: an integrative review. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(11):3154–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1867-6. This integrative review describes current US trends for health technology-enabled adherence interventions among behaviorally HIV-infected youth (ages 13–29 years), and provides data on the feasibility and efficacy of the nine identified interventions. Findings demonstrate the feasibility of computer-based interventions, and initial efficacy of SMS texting for adherence support among HIV-infected youth.

Lenhart A, Pew Research Center. Teen, social media and technology overview. 2015.

Pew Research Center Smartphone ownership and internet usage continues to climb in emerging economies. 2016.

Pew Research Center. Emerging nations embrace internet, mobile Technology 2014.

Pew Research Center. Mobile Fact Sheet. 2017. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed 26 Jan 2018.

Horvath T, Azman H, Kennedy GE, Rutherford GW. Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. The Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012(3):CD009756. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009756.

Mayer JE, Fontelo P. Meta-analysis on the effect of text message reminders for HIV-related compliance. AIDS Care. 2017;29(4):409–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1214674.

• Badawy SM, Barrera L, Sinno MG, Kaviany S, O'Dwyer LC, Kuhns LM. Text Messaging and Mobile Phone Apps as Interventions to Improve Adherence in Adolescents With Chronic Health Conditions: A Systematic Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2017;5(5):e66. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.7798. This systematic review evaluated evidence for the efficacy of text messaging and mobile phone apps as interventions to promote medication adherence among adolescents with chronic health conditions (CHCs). Of 15 publications, [text messaging (n=12) and mobile phone apps (n=3)], the authors found promising feasibility and acceptability and modest efficacy for the use of text messaging and mobile phone app interventions to improve medication adherence among adolescents with CHCs.

Badawy SM, Kuhns LM. Economic evaluation of text-messaging and smartphone-based interventions to improve medication adherence in adolescents with chronic health conditions: a systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2016;4(4):e121. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.6425.

Anand T, Nitpolprasert C, Kerr SJ, Muessig KE, Promthong S, Chomchey N, et al. A qualitative study of Thai HIV-positive young men who have sex with men and transgender women demonstrates the need for eHealth interventions to optimize the HIV care continuum. AIDS Care. 2017;29(7):870–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2017.1286288.

Holloway IW, Winder TJ, Lea CH, III, Tan D, Boyd D, Novak D. Technology use and preferences for mobile phone-based HIV prevention and treatment among black young men who have sex with men: exploratory research. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017;5(4):e46. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.6436.

LeGrand S, Muessig KE, McNulty T, Soni K, Knudtson K, Lemann A, et al. Epic allies: development of a gaming app to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among young HIV-positive men who have sex with men. JMIR Serious games. 2016;4(1):e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/games.5687.

Outlaw AY, Naar-King S, Tanney M, Belzer ME, Aagenes A, Parsons JT, et al. The initial feasibility of a computer-based motivational intervention for adherence for youth newly recommended to start antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Care. 2014;26(1):130–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.813624.

Rana Y, Haberer J, Huang H, Kambugu A, Mukasa B, Thirumurthy H, et al. Short message service (SMS)-based intervention to improve treatment adherence among HIV-positive youth in Uganda: focus group findings. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0125187. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125187.

Saberi P, Yuan P, John M, Sheon N, Johnson MO. A pilot study to engage and counsel HIV-positive African American youth via telehealth technology. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(9):529–32. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2013.0185.

Saberi P, Siedle-Khan R, Sheon N, Lightfoot M. The use of mobile health applications among youth and young adults living with HIV: focus group findings. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2016;30(6):254–60. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2016.0044.

Dowshen N, Kuhns LM, Gray C, Lee S, Garofalo R. Feasibility of interactive text message response (ITR) as a novel, real-time measure of adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV+ youth. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2237–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0464-6.

Dowshen N, Kuhns LM, Johnson A, Holoyda BJ, Garofalo R. Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy for youth living with HIV/AIDS: a pilot study using personalized, interactive, daily text message reminders. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e51. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2015.

Garofalo R, Kuhns LM, Hotton A, Johnson A, Muldoon A, Rice D. A randomized controlled trial of personalized text message reminders to promote medication adherence among HIV-positive adolescents and young adults. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(5):1049–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1192-x.

Linnemayr S, Huang H, Luoto J, Kambugu A, Thirumurthy H, Haberer JE, et al. Text messaging for improving antiretroviral therapy adherence: no effects after 1 year in a randomized controlled trial among adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1944–50. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2017.304089.

Menza TW, Choi SK, LeGrand S, Muessig K, Hightow-Weidman L. Correlates of self-reported viral suppression among HIV-positive, young, black men who have sex with men participating in a randomized controlled trial of an internet-based HIV prevention intervention. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;2017 https://doi.org/10.1097/olq.0000000000000705.

Hightow-Weidman L, LeGrand S, Simmons R, Egger J, Choi SK, Muessig K. healthMpowerment: effects of a mobile phone-optimized, internet-based intervention on condomless anal intercourse among young black men who have sex with men and transgender women. Abstract# WEPEC1001, 2017 International AIDS society conference. Paris, France, July 23-26, 2017.

Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Pike EC, LeGrand S, Baltierra N, Rucker AJ, et al. HealthMpowerment.org: building community through a mobile-optimized, online health promotion intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(4):493–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198114562043.

Naar-King S, Outlaw AY, Sarr M, Parsons JT, Belzer M, Macdonell K, et al. Motivational enhancement system for adherence (MESA): pilot randomized trial of a brief computer-delivered prevention intervention for youth initiating antiretroviral treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(6):638–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss132.

Stankievich E, Malanca A, Foradori I, Ivalo S, Losso M. Utility of mobile communication devices as a tool to improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in HIV-infected children and young adults in Argentina. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1097/inf.0000000000001807.

Inwani I, Chhun N, Agot K, Cleland CM, Buttolph J, Thirumurthy H, et al. High-yield HIV testing, facilitated linkage to care, and prevention for female youth in Kenya (GIRLS study): implementation science protocol for a priority population. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(12):e179. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.8200.

Mavhu W, Willis N, Mufuka J, Mangenah C, Mvududu K, Bernays S, et al. Evaluating a multi-component, community-based program to improve adherence and retention in care among adolescents living with HIV in Zimbabwe: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):478. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2198-7.

Tanner AE, Mann L, Song E, Alonzo J, Schafer K, Arellano E, et al. weCARE: a social media-based intervention designed to increase HIV care linkage, retention, and health outcomes for racially and ethnically diverse young MSM. AIDS Educ Prev. 2016;28(3):216–30. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2016.28.3.216.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Definition of Youth. Fact sheet. 2016. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/youth/fact-sheets/youth-definition.pdf. Accessed 31 Jan 2018.

Gaysynsky A, Romansky-Poulin K, Arpadi S. “my YAP family”: analysis of a Facebook Group for young adults living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):947–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0887-8.

Eysenbach G. CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e126. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1923.

Saberi P, Johnson MO. Correlation of internet use for health care engagement purposes and HIV clinical outcomes among HIV-positive individuals using online social media. J Health Commun. 2015;20(9):1026–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018617.

Crutzen R, Roosjen JL, Poelman J. Using Google analytics as a process evaluation method for internet-delivered interventions: an example on sexual health. Health Promot Int. 2013;28(1):36–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/das008.

Van Gemert-Pijnen EWCJ, Kelders MS, Bohlmeijer TE. Understanding the usage of content in a mental health intervention for depression: an analysis of log data. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(1):e27. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2991.

Kelders MS, Bohlmeijer TE, Van Gemert-Pijnen EWCJ. Participants, usage, and use patterns of a web-based intervention for the prevention of depression within a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e172. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2258.

Graham LM, Strawderman SM, Demment M, Olson MC. Does usage of an eHealth intervention reduce the risk of excessive gestational weight gain? Secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(1):e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6644.

Baltierra NB, Muessig KE, Pike EC, LeGrand S, Bull SS, Hightow-Weidman LB. More than just tracking time: complex measures of user engagement with an internet-based health promotion intervention. J Biomed Inform. 2016;59:299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2015.12.015.

•• Bauermeister JA, Golinkoff JM, Muessig KE, Horvath KJ, Hightow-Weidman LB. Addressing engagement in technology-based behavioural HIV interventions through paradata metrics. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12(5):442–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/coh.0000000000000396. The goal of this review was to examine how often researchers report participants’ online engagement using paradata (i.e. intervention usage metrics) when describing the outcomes of online behavioural HIV prevention and care interventions. The authors provide insights on the utility of paradata collection and analysis for future technology-based trials.

Cherenack EM, Wilson PA, Kreuzman AM, Price GN. The feasibility and acceptability of using technology-based daily diaries with HIV-infected young men who have sex with men: a comparison of internet and voice modalities. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(8):1744–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1302-4.

Spruijt-Metz D, Nilsen W. Dynamic models of behavior for just-in-time adaptive interventions. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2014;13(3):13–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/MPRV.2014.46.

Almirall D, Nahum-Shani I, Sherwood NE, Murphy SA. Introduction to SMART designs for the development of adaptive interventions: with application to weight loss research. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4(3):260–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-014-0265-0.

Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5 Suppl):S112–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022.

Murphy SA, Lynch KG, Oslin D, McKay JR, TenHave T. Developing adaptive treatment strategies in substance abuse research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 2):S24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.008.

Patton GC, Viner R. Pubertal transitions in health. Lancet (London, England). 2007;369(9567):1130–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60366-3.

World Health Organization. Health for the world’s adolescents: a second chance in the second decade. 2014.

Larson R, Richards MH. Daily companionship in late childhood and early adolescence: changing developmental contexts. Child Dev. 1991;62(2):284–300. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131003.

World Health Organization. HIV and adolescents: guidance for HIV testing and counselling and care for adolescents living with HIV. Geneva: WHO; 2013.

Agwu AL, Fairlie L. Antiretroviral treatment, management challenges and outcomes in perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18579. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.16.1.18579.

Koenig LJ, Nesheim S, Abramowitz S. Adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV: emerging behavioral and health needs for long-term survivors. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23(5):321–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0b013e32834a581b.

Lowenthal ED, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Marukutira T, Chapman J, Goldrath K, Ferrand RA. Perinatally acquired HIV infection in adolescents from sub-Saharan Africa: a review of emerging challenges. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(7):627–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70363-3.

World Health Organization. Why focus on adolescents (10–19 years)? http://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section/section_2/level2_3.php. Accessed 2 Febr 2018.

Pew Research Center. Parents, teens and digital monitoring. 2016.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT). U01MD011274 (PI: Bauermeister): Reducing HIV Vulnerability through a Multilevel Life Skills Intervention for Adolescent Men (2016–2021). https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=9322370&icde=37901692&ddparam=&ddvalue=&ddsub=&cr=2&csb=default&cs=ASC&pball. Accessed 4 Febr 2018.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT). U01MD011279 (PI: Schnall): A Pragmatic Clinical Trial of MyPEEPS Mobile to Improve HIV Prevention Behaviors in Diverse Adolescent MSM (2016–2021). https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=9321397&icde=37901692. Accessed 4 Febr 2018.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT). U01MD011281 (PI: Mustankski): A Pragmatic Trial of an Adaptive eHealth HIV Prevention Program for Diverse Adolescent MSM (2016–2020). https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=9562779&icde=37901728&ddparam=&ddvalue=&ddsub=&cr=7&csb=default&cs=ASC&pball. Accessed 4 Febr 2018.

Hightow-Weidman L, Knudtson K, Muessig K, Srivatsa M, Lawrence E, LeGrand S et al. AllyQuest: engaging HIV+ young MSM in care and improving adherence through a social networking and gamified smartphone application (App). Abstract# TUPED1273, 2017 International AIDS Society Conference. Paris, France, July 23–26, 2017.

Scott H, Vittinghoff E, Irvin R, Liu A, Fields S, Magnus M et al. Sex pro: a personalized HIV risk assessment tool for men who have sex with men. Abstract #1017, 2015 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle, Washington, February 23–26, 2015.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kate Muessig for her review of this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health grant (U19HD089881; MPI: Hightow-Weidman/Sullivan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on HIV and Technology

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mulawa, M.I., LeGrand, S. & Hightow-Weidman, L.B. eHealth to Enhance Treatment Adherence Among Youth Living with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 15, 336–349 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-018-0407-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-018-0407-y