Abstract

Purpose of the Review

The number of adults who are aging successfully and have HIV infection is increasing. More effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens are preventing individuals infected with HIV from reaching end stages of the HIV infection and developing AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). However, even at lower viral loads, chronic HIV infection appears to have consequences on aging processes, including the development of frailty.

Recent Findings

Frailty is a term used to describe vulnerability in aging. Frailty indices such as the Fried Frailty Index (FFI), the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) Index, and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D), an index of emotional frailty, associate with or predict clinical outcomes and death. However, even among existing frailty definitions, components require rigorous and consistent standardization. In the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), we have shown that frailty does not exist in isolation, even in midlife, and we use frailty to predict death.

Summary

Frailty indices should be systematically used by health professionals to evaluate health and future risks for adverse events. Frailty prevention efforts, especially among those with HIV infection, appear to be essential for “successful aging” or aging without disability or loss of independence and may prevent HIV transmission. Taking care of elderly people is one of the major challenges of this century, and we must expect and be prepared for an increase in the number of aging adults, some of whom are patients with many co-morbidities and HIV infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adults surviving past age 50 years with HIV infection are increasing at an exceptional and unprecedented rate. This occurs against the backdrop of an aging globe. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that the number of people aged 60 years and older will increase from 900 million to 2 billion between 2015 and 2050 (a shift from 12 to 22% of the total global population) [1]. In addition, between 2000 and 2015, AIDS-related deaths fell by 28% [2]. The availability of antiretroviral medications has played a major role in this demographic shift. In the USA, among people with HIV infection in 2013, 42% were age 50 years and older and 6% were age 65 years and older [3]. The HIV epidemic is a success story of successful treatment and subsequent survival in the twenty-first century. Adults infected with HIV (HIV+) are surviving longer successfully more than at any other time during the epidemic. While trying to cure HIV infection remains important, a priority is to also prevent further infections (there are about 50,000 new infections per year in the USA [3]) and newly occurring age-linked complications. Traditional aging outcomes, including frailty, are now routinely observed among those with HIV infection, even at midlife, and must be addressed. Older HIV+ adults have specific health care needs at the intersection of the HIV infection syndrome and commonly observed aging-related chronic diseases and deficits. Moreover, it appears that those with HIV infection present aging-related symptoms and co-morbidities similar to those found in uninfected older people, at younger ages. Thus, HIV infection has been suggested to cause premature aging [4,5,6]. Understanding why and how the aging process may be disturbed is elemental to developing effective methods of prevention.

In this review, we explore aging in HIV infection from the standpoint of frailty, an aging syndrome, and through the specific lens of HIV infection among women. In so doing, we will describe types of frailty, the potential increased risk of early or premature frailty among women with HIV infection, and share results from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) that have shed light on frailty in women with HIV infection. Finally, we will discuss some general ideas for moving forward with frailty as a dynamic, evolving research area.

Frailty Definition and Assessment Methods

In traditional studies of aging, elderly people are classified into one of three categories: robust, frail, and disabled [7] (see Fig. 1). To be robust is to be without frailty or disability. Frailty is a vulnerability state characterized by impairments and limitations that might lead to disabilities. It represents the vulnerability that increases risk of negative health outcomes, loss of independence, and of mortality [8]. In contrast, being disabled means there are important deficits that restrict a woman from performing daily activities on her own. Whereas frailty seems to be reversible and sensitive to prevention, disability tends to be permanent and may lead to hospitalization, institutionalization, and death. This classification is essential to evaluate health in aging populations and to provide appropriate health care. It is crucial to detect frail adults before they become disabled and to apply active prevention measures of this irreversible state.

According to PubMed, frailty was first reported in 1956, in an article entitled “Frailty of old age and bacterial allergy” [9]. Subsequent to initial, isolated reports, frailty as a health outcome became consistently reported beginning in the late 1980s. Since then, varying definitions of frailty and essential components of frailty have been put forward. For example, frailty has been defined as a clinical syndrome [10]—a composite of physical symptoms, referred to as the frailty phenotype (FP) [11]—and the accumulation of deficits [12, 13]. Underlying all definitions of frailty is the concept that to prevent the sequelae, which includes disability followed by death; the reversible frail state must be identified using a screening tool (see Table 1 for list of published frailty indices). Most geriatric indices and scales used in clinical practice to assess health in aging adults do not assess frailty in its entirety but can be used to assess selected components of the frail state.

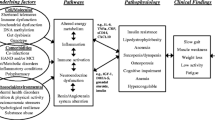

The Fried Frailty Index (FFI), a physical frailty index, was validated in the Cardiovascular Health Study in 1998 and by Kiely in 2009. The FFI is a useful construct to predict poor quality of life, cognitive impairment, dementia, and death [14]. The FFI is composed of five components: weakness, slowness, exhaustion, low physical activity, and unintended weight loss [11]. Fulfilling at least three of the five components denotes frailty. However, the faces of frailty include emotional, social, cognitive, metabolic, and sensory frailty existing alongside physical frailty (see Fig. 2); thus, the FFI has been associated with other health indices such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D scale) [5, 15, 16].

Ten years after introduction of the FFI, the first report on a validated Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) Index, specific for HIV+ adults, was published [17]. The VACS Index is a metabolic (biomarker-based) index with the following components: CD4 count, HIV-1 RNA, hemoglobin, fibrosis-4 (FIB4), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infection. The VACS Index predicts mortality in HIV+ and uninfected (HIV−) populations and is associated with the FFI and death [18, 19].

HIV and Frailty: Greater Risk for Aging Adults with HIV Infection

Frailty and Morbidity

We have explored both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of frailty in the multicenter WIHS. In cross-sectional WIHS analyses, we took a broad-based look at a variety of morbidities that may accompany HIV infection and co-occur and/or contribute to frailty and accelerated or more severe aging. We postulated that middle-aged HIV+ women may present as elderly due to accelerated aging or having more severe aging phenotypes occurring at younger ages, and that, this “aging” phenotype is associated with a multidimensional constellation of factors. In other words, frailty does not occur in isolation.

To address our question, we engaged WIHS frailty measures collected among 2028 HIV+ (n = 1449) and at risk HIV− (n = 579) WIHS women, during midlife (average age 39 years). At midlife, we operationalized the FFI similarly to the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS), which is composed of HIV+ and HIV− men [15]. The WIHS Core battery provided FFI, HIV status, and constellations of variables representing demographic/health behaviors and aging-related chronic diseases. With an age range of 50–64 years, MACS observed 12% frailty prevalence among HIV+ and 9% among HIV− men [20]. In contrast, using similar criteria in the WIHS, the overall frailty prevalence was 15% (HIV+, 17%; HIV−, 10%) among women at midlife. A stepwise multivariable model suggested that HIV infection with CD4 count <200; age >40 years; current or former smoking; income ≤$12,000; moderate vs low FIB-4 levels; and moderate vs high eGFR were positively associated with FFI. Low or moderate drinking was protective. Typical aging-related co-morbidities such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension, as well as recreational drug use and self-reported or historically measured co-infections were not significantly associated with frailty in the final multivariate model. These results show that frailty is a multidimensional aging phenotype observed even in midlife among women with HIV infection; suggest that the frailty constellation may change with age; and show that prevalence of frailty in HIV-infected WIHS women exceeds that for usual elderly populations.

Studies show that adults with HIV infection experience a prevalence of frailty equivalent to and even greater than that observed in elderly [16, 20, 21]. The reason for this early manifestation of frailty may be a consequence of the HIV infection itself, suboptimal medication and control of infection early on, comorbid diseases (infectious or non-infectious) [21, 22] and/or other lifestyle habits, such as smoking and substance use, which are more common among those with HIV infection [23]. Physical frailty may be due to the HIV infection, itself. With a dropping CD4 cell count, the immune system is insufficient to protect against both infectious and chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiac diseases, and diabetes. Moreover, HIV infection is accompanied by numerous symptoms that weaken the body, including pain, weight loss, and fatigue or weakness [24]. Physical deterioration leads to vulnerability to diverse pathologies, which can lead to premature frailty among HIV-infected.

Frailty and Death

We are also predicting death by frailty indices within the WIHS. Why would multi-dimensional frailty indices be associated with mortality in adults with HIV infection? Throughout adult life, HIV infection is synergistic with adverse aging influences on the immune, vascular, reproductive, and central nervous system, thereby intensifying the aging process [25, 26]. As aforementioned, aging with HIV infection is associated with geriatric morbidities or syndromes, including frailty [27]; however, these aging morbidities often occur earlier among those with HIV infection compared to uninfected individuals [4, 5, 28]. The question is whether HIV infection leads to more severe aging phenotypes, or accelerates their onset leading to earlier age of death, or is a cumulative marker of multiple morbidities [29].

Several frailty indices have been used to predict mortality in women with HIV infection—the FFI, the VACS Index, and the CES-D score. Each index is considered a measure of frailty, since each worsens with age and denotes vulnerability [17, 21]. For example, the FFI predicts death in elderly (65 years and older) [30], as well as in younger adult populations who may be at risk for premature or earlier aging, such as those with HIV infection [18, 31]. Several HIV studies have found CES-D to be a significant “independent” predictor of mortality [21, 32,33,34,35,36], however, do not consider measures of FFI and/or VACS in relation to death. The VACS Index also predicts death, in combination with the CES-D [21, 37]. However, our analyses will differ from other studies, since we are evaluating all three indices together in the same model to see which one(s) are most relevant. No other study has included a simultaneous evaluation of these three primary mortality indices considered in HIV research. This will be the first simultaneous evaluation of three common mortality indices in HIV-infected adults reflecting physical, mental, and biological aging and death.

Inclusion of the CES-D as an emotional frailty index and predictor of death originates from the incapacitating psychosocial conditions linked to HIV infection and that lead to depressive symptoms, loneliness, and isolation because of discrimination and stigmatization [33]. Hopelessness and helplessness, as well as anger, suicidal thoughts and feelings, and abandonment are also prevalent [33]. This profile may lead to cognitive frailty and premature aging. Those HIV-infected adults might not be able to find or keep a job, contributing to a low socioeconomic status, also predisposes to the frailty phenotype [20]. Low income denotes a lack of resources to invest in health and disease prevention, which creates vulnerability to diverse negative health outcomes and complications.

Thus, in the WIHS we are simultaneously evaluating, among HIV-infected women on ART, the association of the VACS, FFI, and CES-D with death (both AIDS- and non-AIDS-related). All indices are measured in midlife (average age 39 years), and the follow-up evaluation time is approximately 8 years. This follow-up period is divided into short-term (within 0–3 years) and long-term (>3–8 years) deaths, since studies in elderly show that prediction of death may vary depending on the number of years between the exposure of interest and death.

At the time of this review, the median age of the WIHS participants is 50 years (see Table 2 for the age distribution of WIHS participants). Our ability to continue to explore risk and protective factors for healthful aging will continue given the solid foundation of over 20 years of follow-up of these women. Evaluating vulnerabilities in middle-aged HIV+ women is important to understanding the impact of HIV infection on mortality over the life course. This approach has been shown for other diseases of later life [38]. Midlife physical, biological, and/or mental indicators against the background of HIV infection may be associated with earlier death.

With the increase in numbers of chronically HIV+ aging adults, it may be important to develop new indices to evaluate frailty that include components related to the infection. With the growing population of aging and HIV+ women in the world, a frailty index for HIV+ women would be an invaluable asset, as well as for the development of more precise and effective measures to prevent further disabilities.

Conclusions

Ideas for Going Forward

This overview of frailty among participants in the WIHS highlights the need for geriatricians and gerontologists to interact with younger “at risk” populations and assist in the formulation of best recommendations for frailty interventions to prevent early aging, excess morbidities, and early death. In terms of preventing frailty, implementation of prevention measures should be adapted to the patient’s health, needs, and motivation. Family and social networks should be assessed as well to determine support needs.

Some platforms have been created to assess frailty among populations without HIV infection, like the Platform for the Evaluation of Frailty and the Prevention of Disability, created in October 2011, in Toulouse, France. This innovative initiative permits physicians to screen frail patients, based on the Gérontopôle Frailty Screening Tool (GFST) [39]. More platforms may be created in the years to come, in response to the current high public health demand in certain areas of the world to specifically screen for frailty due to the aging of the world’s population [1]. Furthermore, medical practitioners should be aware of the frail condition and be able to detect frail patients to be able to provide them with appropriate, symptom-specific care. Frailty risk assessment should be included in practitioner education and be a part of the continuous training health-related professionals receive during their career.

For women with HIV infection, aside from typical components of the geriatric syndrome [27], key modifiable factors associated with frailty, as identified in the WIHS [20, 21] and other studies [13, 15, 28, 31], are listed in Table 3. Sarcopenia [40], an aging-related change in the skeletal muscle, is especially of interest for measures of physical frailty. In addition, there is the irony of co-existing excess vascular risk due to HIV treatment and the influence of vascular risk on mortality [41,42,43,44,45]. Since frailty is a syndrome, there are numerous paths for age-specific intervention. Both personalized medicine and public health approaches are necessary, since personalized medicine approaches are based on risk factor and health behavior profiles derived from population and community studies. Among women who are frail, depending on their age, there may be an opportunity to reverse frailty and/or lessen its impact on quality of life.

References

World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS fact sheet. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. HIV among people aged 50 and over. In: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention NCfHA, Viral Hepatitis, Sexual Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis Prevention, editor. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016.

Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LP, et al. HIV-1 infection is associated with an earlier occurrence of a phenotype related to frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(11):1279–86.

Desquilbet L, Margolick JB, Fried LP, et al. Relationship between a frailty-related phenotype and progressive deterioration of the immune system in HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(3):299–306.

Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):542–53.

Subra J, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Cesari M, Oustric S, Vellas B, Platform T. The integration of frailty into clinical practice: preliminary results from the Gerontopole. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(8):714–20.

Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. ScientificWorldJournal. 2001;1:323–36.

Parfentjev IA. Frailty of old age and bacterial allergy. Geriatrics. 1956;11(6):260–2.

Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferrucci L, et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(6):991–1001.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56.

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722–7.

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty defined by deficit accumulation and geriatric medicine defined by frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(1):17–26.

Hirsch C, Anderson ML, Newman A, et al. The association of race with frailty: the cardiovascular health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(7):545–53.

Althoff KN, Jacobson LP, Cranston RD, et al. Age, comorbidities, and AIDS predict a frailty phenotype in men who have sex with men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(2):189–98.

Terzian AS, Holman S, Nathwani N, et al. Factors associated with preclinical disability and frailty among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in the era of cART. J Women’s Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(12):1965–74.

Justice AC, Modur SP, Tate JP, et al. Predictive accuracy of the Veterans Aging Cohort Study index for mortality with HIV infection: a North American cross cohort analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(2):149–63.

Escota GV, Patel P, Brooks JT, et al. Short communication: The Veterans Aging Cohort Study Index is an effective tool to assess baseline frailty status in a contemporary cohort of HIV-infected persons. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2015;31(3):313–7.

Justice AC, Dombrowski E, Conigliaro J, et al. Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS): overview and description. Med Care. 2006;44(8 Suppl 2):S13–24.

Gustafson DR, Shi Q, Thurn M, et al. Frailty and constellations of factors in aging HIV-infected and uninfected women—the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. J Frailty Aging. 2016;5(1):43–8.

Cohen MH, Hotton AL, Hershow RC, et al. Gender-related risk factors improve mortality predictive ability of VACS Index among HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(5):538–44.

Verucchi G, Calza L, Manfredi R, Chiodo F. Human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfection: epidemiology, natural history, therapeutic options and clinical management. Infection. 2004;32(1):33–46.

Piggott DA, Muzaale AD, Mehta SH, et al. Frailty, HIV infection, and mortality in an aging cohort of injection drug users. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54910.

Lee KA, Gay C, Portillo CJ, et al. Symptom experience in HIV-infected adults: a function of demographic and clinical characteristics. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2009;38(6):882–93.

Kalayjian RC, Landay A, Pollard RB, et al. Age-related immune dysfunction in health and in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease: association of age and HIV infection with naive CD8+ cell depletion, reduced expression of CD28 on CD8+ cells, and reduced thymic volumes. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(12):1924–33.

Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(3):453–72.

Greene M, Covinsky KE, Valcour V, et al. Geriatric syndromes in older HIV-infected adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(2):161–7.

Desquilbet L, Jacobson LP, Fried LP, et al. A frailty-related phenotype before HAART initiation as an independent risk factor for AIDS or death after HAART among HIV-infected men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(9):1030–8.

Onen NF, Overton ET. A review of premature frailty in HIV-infected persons; another manifestation of HIV-related accelerated aging. Curr Aging Sci. 2011;4(1):33–41.

Shamliyan T, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Association of frailty with survival: a systematic literature review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(2):719–36.

Erlandson KM, Schrack JA, Jankowski CM, Brown TT, Campbell TB. Functional impairment, disability, and frailty in adults aging with HIV-infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11(3):279–90.

Cohen MH, French AL, Benning L, et al. Causes of death among women with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. Am J Med. 2002;113(2):91–8.

Cook JA, Grey D, Burke J, et al. Depressive symptoms and AIDS-related mortality among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive women. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1133–40.

Coughlin SS. Invited commentary: prevailing over acquired immune deficiency syndrome and depressive symptoms. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(2):126–8. discussion 9-30

Farinpour R, Miller EN, Satz P, et al. Psychosocial risk factors of HIV morbidity and mortality: findings from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25(5):654–70.

Lyketsos CG, Hoover DR, Guccione M, et al. Depressive symptoms as predictors of medical outcomes in HIV infection. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study JAMA. 1993;270(21):2563–7.

Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Skanderson M, et al. Towards a combined prognostic index for survival in HIV infection: the role of ‘non-HIV’ biomarkers. HIV Med. 2010;11(2):143–51.

Ritchie K, Ritchie CW, Yaffe K, Skoog I, Scarmeas N. Is late-onset Alzheimer’s disease really a disease of midlife? Translational CliRes Clin Interventions. 2015;1:122–30.

Vellas B, Balardy L, Gillette-Guyonnet S, et al. Looking for frailty in community-dwelling older persons: the Gerontopole Frailty Screening Tool (GFST). J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(7):629–31.

Afilalo J. Conceptual models of frailty: the sarcopenia phenotype. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(9):1051–5.

Crystal HA, Weedon J, Holman S, et al. Associations of cardiovascular variables and HAART with cognition in middle-aged HIV-infected and uninfected women. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(5):469–76.

Hanna DB, Post WS, Deal JA, et al. HIV infection is associated with progression of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(4):640–50.

Kaplan RC, Kingsley LA, Sharrett AR, et al. Ten-year predicted coronary heart disease risk in HIV-infected men and women. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(8):1074–81.

Kaplan RC, Landay AL, Hodis HN, et al. Potential cardiovascular disease risk markers among HIV-infected women initiating antiretroviral treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(4):359–68.

Seaberg EC, Benning L, Sharrett AR, et al. Association between human immunodeficiency virus infection and stiffness of the common carotid artery. Stroke. 2010;41(10):2163–70.

Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Balfour JL, Higby HR, Kaplan GA. Antecedents of frailty over three decades in an older cohort. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(1):S9–16.

Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(7):601–8.

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of Adl: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98.

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;385-401

Graf C. Hartford Institute for Geriatric N. The Lawton instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scale. Medsurg Nurs. 2008;17(5):343–4.

Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel R. User’s Manual for the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Core Measures of Health-Related Quality of Life: Rand Corporation; 1995.

Hall KS, Hendrie HC, Brittain HM. The development of a dementia screening screening interview in two distince languages. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1993;3:1–28.

Sayers SP, Jette AM, Haley SM, Heeren TC, Guralnik JM, Fielding RA. Validation of the late-life function and disability instrument. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1554–9.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the following: State University of New York Downstate Medical Center institutional research support; the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff, Deborah Gustafson); Washington DC, Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); the Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); and the Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632). The study is co-funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All aspects of this review are compliant with the ethical guidelines enforced by the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center, USA.

Conflict of Interest

Marion Thurn and Deborah R. Gustafson have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article contains reference to human research studies, some performed by Dr. Gustafson. All studies cited or conducted within the WIHS are approved by ethical review boards at each WIHS site. The Institutional Review Boards of each WIHS site have reviewed and approved all data collection and analyses for the WIHS.

Disclaimer

The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Behavioral-Bio-Medical Interface

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thurn, M., Gustafson, D.R. Faces of Frailty in Aging with HIV Infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 14, 31–37 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-017-0348-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-017-0348-x